ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Type 2 diabetes patients often initiate treatment with a sulfonylurea and subsequently intensify their therapy with insulin. However, information on optimal treatment regimens for these patients is limited.

OBJECTIVE

To compare risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and hypoglycemia between sulfonylurea initiators who switch to or add insulin.

DESIGN

This was a retrospective cohort assembled using national Veterans Health Administration (VHA), Medicare, and National Death Index databases.

PARTICIPANTS

Veterans who initiated diabetes treatment with a sulfonylurea between 2001 and 2008 and intensified their regimen with insulin were followed through 2011.

MAIN MEASURES

The association between insulin versus sulfonylurea + insulin and time to CVD or hypoglycemia were evaluated using Cox proportional hazard models in a 1:1 propensity score-matched cohort. CVD included hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction or stroke, or cardiovascular mortality. Hypoglycemia included hospitalizations or emergency visits for hypoglycemia, or outpatient blood glucose measurements <60 mg/dL. Subgroups included age < 65 and ≥ 65 years and estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥ 60 and < 60 ml/min.

KEY FINDINGS

There were 1646 and 3728 sulfonylurea monotherapy initiators who switched to insulin monotherapy or added insulin, respectively. The 1596 propensity score-matched patients in each group had similar baseline characteristics at insulin initiation. The rate of CVD per 1000 person-years among insulin versus sulfonylurea + insulin users were 49.3 and 56.0, respectively [hazard ratio (HR) 0.85, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.64, 1.12]. Rates of first and recurrent hypoglycemia events per 1000 person-years were 74.0 and 100.0 among insulin users compared to 78.9 and 116.8 among sulfonylurea plus insulin users, yielding HR (95 % CI) of 0.94 (0.76, 1.16) and 0.87 (0.69, 1.10), respectively. Subgroup analysis results were consistent with the main findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Compared to sulfonylurea users who added insulin, those who switched to insulin alone had numerically lower CVD and hypoglycemia events, but these differences in risk were not statistically significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) consensus statement on the management of individuals with diabetes recommends metformin as first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes.1 However, among U.S. veterans, 43 % of newly diagnosed diabetes patients initiated treatment with a sulfonylurea (Roumie et al., under review). This could be due to ease of regimen initiation (no titration usually needed), providers’ preference or contraindications to metformin use (e.g., patients with impaired kidney function due to concerns for lactic acidosis).2–6

Although the optimal strategy to intensify initial sulfonylurea monotherapy remains unclear, experts have recommended that intensification may be accomplished by insulin as add-on therapy or insulin monotherapy.7–9 However, evidence comparing important clinical outcomes between these specific intensification regimens is lacking. Furthermore, there are continued concerns that insulin and sulfonylureas may increase cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk compared to metformin, despite their ability to effectively achieve glycemic control.10–13 In addition, both sulfonylureas and insulin cause hypoglycemia, which remains a major therapy-limiting concern of both patients and providers.14–16

In this study, our aim was to investigate the risk of several important clinical outcomes among U.S. veterans who intensified their initial sulfonylurea monotherapy by switching to insulin alone or adding insulin. We specifically focused on CVD as a long-term outcome and hypoglycemia as a short-term outcome.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

We assembled a retrospective cohort of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients who initiated treatment for type 2 diabetes. Information on these patients included dispensed medications (date filled, days supplied and pill/vial number)17; demographics; and ICD9-CM coded diagnostic and procedure information from inpatient and outpatient encounters.18 We collected laboratory results from clinical sources. Vital signs data included all outpatient height, weight and blood pressure measurements. For enrollees in Medicare or Medicaid, we obtained enrollment, inpatient and outpatient claims files, and prescription (Part D) data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services through the VHA’s interagency exchange agreement.19,20 We obtained dates of death from VHA vital status files and causes of death from National Death Index (NDI) data.21 The institutional review boards of Vanderbilt University and VHA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System approved this study.

Study Population

The study population comprised U.S. veterans aged 18 years or older who filled a new prescription for sulfonylurea monotherapy between October 2001 and September 2008; had not filled any antihyperglycemic drug in the prior 180 days; and had at least one encounter or prescription fill every 180 days during the prior 2 years. New users of sulfonylurea monotherapy were followed through September 2011 for a new insulin prescription fill, and became eligible for the treatment intensification cohort at that time (Supplemental Figure 1). Because we were interested in patients who intensified due to failing sulfonylurea monotherapy, we excluded patients who were considered non-adherent at the time insulin was prescribed. To accomplish this, we excluded patients who had no sulfonylurea supply remaining in the 180 days prior to the date of first insulin prescription, based on their prescription fill records. We also excluded patients with hospice care; dialysis or baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 15 ml/min; organ/ bone marrow transplant; and missing baseline serum creatinine at therapy intensification or in the prior 730 days.

Exposures

The two comparison groups were: patients who switched to insulin (long-acting, premixed, or short/fast-acting insulin) and patients who continued sulfonylurea (glyburide, glipizide or glimepiride) with the addition of insulin. The treatment intensification regimen was defined and follow-up began at 180 days after the first insulin prescription, to distinguish patients who continued both sulfonylurea and insulin from those who switched to insulin monotherapy. Follow-up continued until study outcome, death, loss to follow-up (no contact with VHA for > 180 days) or study end (30 September 2011). Patients were also censored if they had a regimen change or were non-persistent on their study regimen (90 days with no insulin prescription fill). In a previous study, we showed that the 90-day gap definition of treatment persistence approximated 80 % adherence to the regimen in our study population.22

Co-Primary Outcomes: Cardiovascular Disease and Hypoglycemia

Fatal and Nonfatal Cardiovascular Disease

The composite cardiovascular outcome was fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. Nonfatal events included hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or stroke (Supplemental Table 1). These definitions previously yielded a positive predictive value between 81 and 90 % compared with review of VHA medical records.23 Fatal cardiovascular events included any death identified based on NDI death certificates with an ICD-10 coded underlying cause of death including I00-I78 (cardiovascular deaths) or R98, R99, R960, R961 (unattended deaths), excluding I30.X (diseases of the pericardium). This approach was derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and reports that validated strategies for identification of sudden cardiac deaths.24,25

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia events were defined as inpatient hospitalizations or emergency department (ED) visits for hypoglycemia, or outpatient blood glucose measurements < 60 mg/dl (Supplemental Table 1). The ED hypoglycemia algorithm yielded a positive predictive value of 89 % compared with records review in a previous study.26 For blood glucose values obtained in the outpatient setting, we applied some data quality control measures. We excluded non-numeric values (such as “high” or “low”), and converted non-absolute values to absolute values so that a glucose value > 400 would be coded as 400, and a glucose value < 70 would be coded as 70. If a patient had hypoglycemia based on the outpatient blood glucose or ED visit which led to a hospitalization within 48 hours, the event was counted as a single event attributed to the hospitalization. Similarly, if a patient had hypoglycemia based on the outpatient blood glucose which led to an emergency visit, the event was considered as a single ED visit.

Secondary Outcomes: Glycated Hemoglobin and Body Mass Index, Chronic Kidney Disease, All-Cause Death

Glycated Hemoglobin and Body Mass Index

We compared differences in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels and body mass index (BMI) between the treatment groups at 12, 24, and 36 months following initiation of insulin. HbA1c and BMI measurements at baseline were collected on the date of insulin initiation or on the closest date within the prior 730 days. Subsequent measurements at 12, 24, and 36 months were from each specific month or carried forward from the closest measurement in the prior 730 days. Any implausible values for HbA1c (< 3 %, > 30 %), height (< 48 inches, > 90 inches), and weight (< 50 pounds, > 700 pounds) were excluded.

Chronic Kidney Disease

All eGFRs were estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.27 Serum creatinine levels < 0.3 mg/dl were considered implausible and were excluded. eGFR values ≥ 150 ml/min were truncated at 150 ml/min. Non-IDMS (isotope dilution mass spectrometry) calibrated creatinine was adjusted by 5 %.29 The composite chronic kidney disease outcome was a sustained 30 % decline in outpatient eGFR measurement or an event indicating end stage renal disease (ESRD),28 including dialysis, renal transplant, or reaching eGFR < 15 ml/min (Supplemental Table 1). All events, except for renal transplant, required a second event that confirmed the decline in eGFR or dialysis event within 3 to 12 months. The date of the confirmatory event was the outcome date.

All-Cause Death

We determined all-cause death using the VHA Vital Status file, which combines information from multiple sources (Medicare, VHA, Social Security and VHA compensation and pension benefits) to determine vital status and date of death.29,30 When the VHA date of death conflicted with the NDI date of death (< 3 %), we used the NDI date of death.

Statistical Analyses

Each outcome was analyzed separately. We evaluated the time to CVD and hypoglycemia (first event following insulin initiation and recurrent events), for insulin alone compared to sulfonylurea + insulin in a propensity score-matched cohort. The propensity score modeled the probability of insulin monotherapy based on multiple baseline characteristics and Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) of care (Supplemental Tables 2–3). A 1:1 greedy matching algorithm was used to construct the matched cohort (Supplemental Figure 2; Supplemental Table 3).31,32

Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare outcomes for insulin versus sulfonylurea + insulin (reference) in the matched cohort. For recurrent hypoglycemia analyses, robust standard errors were utilized to account for multiple events within individual patients. The fulfillment of the proportional hazards assumptions was verified through examination of log-log survival plots. Secondary outcomes of CKD and death were analyzed using a similar strategy. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the median differences in HbA1c and BMI at 12, 24, and 36 months after intensification between the matched groups.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

We assessed for effect modification through stratification by age (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years) and baseline eGFR (< 60 ml/min and ≥ 60 ml/min). We also evaluated the significance of corresponding interaction terms, using likelihood ratio tests. As part of sensitivity analyses, we used two alternate definitions for the hypoglycemia outcome; first using only hospitalizations and ED visits, and second using hospitalizations and ED visits for hypoglycemia and outpatient blood glucose <50 mg/dL. We also examined whether rates of hypoglycemia differed according to the type of sulfonylurea patients were receiving. We compared insulin to glyburide + insulin or glipizide/glimepiride + insulin as the reference group. Analyses were conducted using R (available at: http://www.r-project.org/), Stata 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and SAS for Windows 9.2. (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Cohort and Patient Characteristics

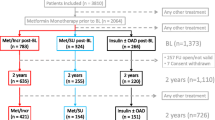

We identified 323,857 veterans who initiated diabetes treatment. Of these, 55 % initiated metformin, 43 % sulfonylurea and 2 % other regimens. There were 144,110 patients who initiated sulfonylurea monotherapy. Approximately 49 % never intensified sulfonylurea monotherapy over a median follow-up of 50 months (interquartile range [IQR] 19, 71). Of 74,115 patients who intensified therapy, we excluded 10,339 patients (14 %) who became non-adherent to sulfonylurea before changing to a different regimen (no sulfonylurea prescriptions filled in the 6 months prior to treatment intensification). We also excluded 3342 (5 %) with < 6 months of follow-up required to define the intensification regimen. Most patients (N = 53,240 [72 %]) changed to a non-insulin based-regimen, often switching to or adding metformin. There were 7194 patients who intensified with an insulin regimen. We further excluded 1820 patients (25 %), including those with hospice, dialysis, or transplant codes, missing baseline creatinine, baseline eGFR <15 ml/ min and data errors (Fig. 1).

Cohort patients were typical of most VHA patients with 98 % being male and 70 % white. Insulin patients and sulfonylurea + insulin patients had similar age, HbA1c, and eGFR at baseline. After propensity score matching, there were 1596 matched patients in each group. Baseline characteristics were similar both before and after propensity score matching (Table 1; Supplemental Table 4). Among those in the matched cohort who used insulin versus sulfonylurea + insulin, 33 % versus 52 % used long-acting; 22 % versus 13 % premixed; 5 % versus 11 % short-acting; and 31 % versus 18 % both long and short-acting insulins. The remaining patients in the matched cohort (9 % insulin and 6 % sulfonylurea + insulin) used other insulin combinations.

The median follow-up before censoring or death was 1.1 years (IQR 0.4, 2.5) among insulin patients and 1.0 year (IQR 0.4, 2.3) among sulfonylurea + insulin patients. Patients were censored for non-persistence on therapy (52 % insulin alone versus 54 % sulfonylurea + insulin), leaving VHA (1 % versus 0.6 %) or reaching study end (29 % versus 29 %).

Absolute and Relative Incidence of Fatal and Nonfatal Cardiovascular Events

There were 128 composite events (54 AMI and stroke hospitalizations, 74 cardiovascular deaths) among 1596 patients on insulin, and 134 events (44 AMI and stroke hospitalizations, 90 cardiovascular deaths) among 1596 patients on sulfonylurea + insulin. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) events per 1000 person-years and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were 49.3 (41.2, 58.3) and 56.0 (47.1, 65.9), respectively [hazard ratio (HR) (0.89, 95 % CI 0.70, 1.10)] (Table 2).

Absolute and Relative Incidence of Hypoglycemia Events

There were 179 first hypoglycemia events (47 hospitalizations or ED visits and 132 outpatient glucose < 60 mg/dL) among patients on insulin, and 174 events (48 hospitalizations or ED visits and 126 outpatient glucose < 60 mg/dL) among patients on sulfonylurea + insulin. The event rates per 1000 person-years and 95 % CIs were 74.0 (63.9, 85.6) and 78.9 (68.0, 91.5), respectively (HR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.76, 1.16) (Table 2). The recurrent event rates per 1000 person-years and 95 % CIs were 100.0 (85.1, 118.3) and 116.8 (98.5, 139.4), respectively (HR 0.87, 95 % CI 0.69, 1.10) (Table 2).

Secondary Outcomes

Median HbA1c levels decreased after 12 months and were maintained in both groups, but were modestly lower in the insulin monotherapy group with median differences of −0.2 % and −0.4 % at 24 and 36 months (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2a). Median BMI increased progressively and similarly in both groups overtime (Fig. 2b).

There were 218 chronic kidney disease (CKD) events among insulin patients (197 with eGFR decline of >30 % and 21 with ESRD events), and 174 events among matched sulfonylurea + insulin patients (158 eGFR decline of > 30 % and 16 ESRD events). CKD events per 1000 person-years and 95 % CIs were 94.9 (83.3, 107.7) and 78.5 (67.7, 90.5), respectively (HR 1.22, 95 % CI 1.00, 1.49) (Table 2).

There were 285 and 267 deaths among insulin patients and sulfonylurea + insulin patients, respectively. Deaths per 1000 person-years and 95 % CIs were 106.9 (95.4, 119.2) and 108.8 (96.8, 121.8), respectively (HR 0.99, 95 % CI 0.84, 1.17) (Table 2).

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Subgroup analyses stratified by age and eGFR demonstrated results consistent with the primary analysis (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 5). Furthermore, in models evaluating all-cause death the interaction terms between exposure regimens and age and eGFR were not statistically significant in likelihood ratio tests (p = 0.301 and p = 0.433, respectively). Results from sensitivity analyses with alternate definitions for hypoglycemia were consistent with results from the primary analyses. Similarly, results were consistent when insulin was compared to glyburide + insulin or glipizide/glimepiride + insulin (Supplemental Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In a large cohort study of predominantly male veterans on sulfonylurea monotherapy, patients who intensified treatment by switching to insulin compared with adding insulin had no statistically significant difference in the risk of CVD, hypoglycemia, CKD, or death. However, due to modest size and limited follow-up of our cohort, we could not rule out small to moderate differences in risk. Patients on insulin alone had a modestly greater decrease in HbA1c during follow-up years.

This study compared insulin alone versus sulfonylurea + insulin on both long-term and short-term serious outcomes: CVD and hypoglycemia, respectively. A few previous studies have examined clinical endpoints such as hypoglycemia, HbA1c and weight gain between these treatments. In a sub-study of the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), hypoglycemia occurred less frequently with sulfonylurea ± insulin compared with insulin alone (1.6 % vs. 3.2 % per year, respectively), and a higher proportion of patients achieved HbA1c < 7 % (47 % vs. 35 %). Weight gain over the 6 years of follow-up was similar.33 Another large observational study found serious hypoglycemia was more common among those taking sulfonylurea + insulin, compared to either insulin alone or sulfonylurea alone (3.4 %, 2.8 %, and 1.2 %, respectively).34 In a meta-analysis of 17 clinical trials published from 1966 through 1991, a modest improvement in glycemic control and similar weight gain was demonstrated with sulfonylurea + insulin compared to insulin alone.35 While these results were contrary to our finding that insulin alone led to lower HbA1c, the between-group differences were very small and likely not clinically different. This may in part be due to the smaller sample size of our groups overtime.

Part of the rationale for the combination of oral hypoglycemic and insulin therapy is that the patient can retain the convenience of oral agents and minimize total exogenous insulin requirements.36 Although there is evidence that combination therapy can decrease exogenous insulin requirements, this reduction is small.35 In addition, there is little evidence that a modest reduction in insulin use is accompanied by significant differences in weight, hypoglycemia risk, or other long-term clinical benefits such as CVD or CKD prevention. Given our current findings of no large increased risk of clinical outcomes with the use of insulin alone compared with combination of sulfonylurea and insulin, the decision about which regimen to use should be tailored to the individual patient by addressing the potential benefit of using lower insulin dose in combined therapy versus the benefit of regimen simplicity and lower costs (one drug versus two).

Our findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations. Only 5 % of our large inception cohort of sulfonylurea monotherapy users initiated insulin during study follow-up, which limited our sample size and the precision of our estimates. Although large medication effects on the outcomes risks seem unlikely, based on the estimated confidence intervals, more modest effects cannot be ruled out. The hypoglycemia outcome definitions used in our analysis yielded event rates similar to those reported by other groups; however a different definition (either more or less inclusive or serious hypoglycemia) could systematically lead to higher or lower event rates than that which we reported. Importantly, our findings were robust to the use of alternate hypoglycemia definitions. We utilized refill data as a proxy for medication taking, which may result in exposure misclassification, and medication doses were not explored. Nevertheless, prescription fills appear to be a good proxy for medication use.37,38 Veterans may not receive all their care or medications in VHA facilities, which could result in missing events or medications. We supplemented our VHA data with Medicare and Medicaid information to reduce the possibility of missing outcomes, and results were similar when stratified by age 65 years and older compared to those less than 65 years of age. We utilized propensity scores and matched on multiple baseline covariates for analysis; however, residual confounding by indication or differences in severity of diabetes remains a possibility. Finally, this study was conducted in veterans, the majority of whom are white men, which must be considered when generalizing our results to other populations.

In conclusion, we found no clinically significant differences in the risk of fatal and non-fatal CVD, hypoglycemia, and other long and short-term outcomes between sulfonylurea initiators who switched to insulin monotherapy and those who added insulin onto sulfonylurea therapy, although modest differences in risk could not be ruled out. Other risks and benefits of each regimen should be discussed with patients to individualize their treatments.

REFERENCES

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstall RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140–149.

Glucophage final printed labeling 2001.

Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, Bailey CJ, McGuire DK. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312:2668–2675.

Abrahamson MJ. Should sulfonylureas remain an acceptable first-line add-on to metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes? Yes, they continue to serve us well! Diabetes Care. 2015;38:166–169.

National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:850–886.

Genuth S. Should sulfonyolureas remain an acceptable first-line add-on to metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes? No, it’s time to move on! Diabetes Care. 2015;38:170–175.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstall RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–1379.

Feil DG, Rajan M, Soroka O, Tseng CL, Miller DR, Pogach LM. Risk of hypoglycemia in older veterans with dementia and cognitive impairment: implications for practice and policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2263–2272.

Libby AM, Pace W, Bryan C, Anderson HO, Ellis SL, Allen RR, Brandt E, Huebschmann AG, West D, Valuck RJ. Comparative effectiveness research in DARTNet primary care practices: point of care data collection on hypoglycemia and over-the-counter and herbal use among patients diagnosed with diabetes. Med Care. 2010;48:S39–44.

Stoekenbroek RM, Rensing KL, Bernelot Moens SJ, Nieuwdorp M, DeVries JH, Zwinderman AH, Stroes ES, Currie CJ, Hutten BA. High daily insulin exposure in patients with type 2 diabetes is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240:318–323.

Rensing KL, Reuwer AQ, Arsenault BJ, von der Thusen JH, Hoekstra JBL, Kastelein JJP, Twickler TB. Reducing cardiovascular disease risk in patients with type 2 diabetes and concomitant macrovascular disease: can insulin be too much of a good thing? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:1073–1087.

Roumie CL, Greevy RA, Grijalva CG, Hung AM, Liu X, Murff HJ, Elasy TA, Griffin MR. Association between intensification of metformin treatment with insulin vs sulfonylureas and cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2014;311:2288–2296.

Schramm TK, Gislason GH, Vaag A, Rasmussen JN, Folke F, Hansen ML, Føsbol EL, Køber L, Norgaard ML, Madsen M, Hansen PR, Torp-Pedersen C. Mortality and cardiovascular risk associated with different insulin secretagogues compared with metformin in type 2 diabetes, with or without a previous myocardial infarction: a nationwide study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1900–1908.

Williams SA, Shi L, Brenneman SK, et al. The burden of hypoglycemia on healthcare utilization, costs, and quality of life among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Diabetes Complicat. 2012;26:399–406.

Johnston SS, Smith DM, Conner C, et al. Evidence linking hypoglycemic events to an increased risk of acute cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1164–70.

Bonds DE, Miller ME, Bergenstal RM. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycaemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes: retrospective epidemiological analysis of the ACCORD study. BMJ. 2010;340:b4909.

Arnold N, Hines D, Stroupe K. Comparison of VA Outpatient Prescriptions in the DSS Datasets and the PBM Database. In: Center VIR, ed. VIREC Technical Report #1. Hines, IL: Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital; 2006.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Washington, DC: Public Health Service, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1988.

Humensky J, Carretta H, de Groot K, Brown MM, Tarlov E, Hynes D. Service Utilization of Veterans Dually Eligible for VA and Medicare Fee-For-Service: 1999–2004. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review 2012;2.

Hynes DM, Koelling K, Stroupe K. Veterans' access to and use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care. 2007;45:214–23.

McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ilgen M, Zivin K, Blow FC. Suicide mortality among patients receiving care in the veterans health administration health system. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1033–1038.

Greevy RA Jr, Huizinga MM, Roumie CL. Comparisons of persistence and durability among three oral antidiabetic therapies using electronic prescription-fill data: the impact of adherence requirements and stockpiling. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:813–9.

Niesner K, Murff HJ, Griffin MR, Wasserman B, Greevy RA, Grijalva CG, Roumie CL. Validation of VA administration data algorithms for identifying cardiovascular disease hospitalization. Epidemiology. 2013;24:334–335.

Chung CP, Murray KT, Stein CM, Hall K, Ray WA. A computer case definition for sudden cardiac death. Pharmacoepidmiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:563–572.

Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, Meador KG, Hall K, Murray KT. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1161–1167.

Ginde AA, Blanc PG, Lieberman RM. Validation of ICD-9-coding algorithm for improved identification of hypoglycemia visits. BMC Endocr Disord. 2008;8:4.

Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward M, Emberson JR, Jafar TH, Jee SH, Polkinghorne KR, Shankar A, Smith DH, Tonelli M, Warnock DG, Wen CP, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT, Hemmelgarn BR, Levey AS. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA. 2012;307:1941–1951.

Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ballew SH, Appel LJ, Arima H, Chadban SJ, Cirillo M, Djurdjev O, Green JA, Heine GH, Inker LA, Irie F, Ishani A, Ix JH, Kovesdy CP, Marks A, Ohkubo T, Shalev V, Shankar A, Wen CP, de Jong PE, Iseki K, Stengel B, Gansevoort RT, Levey AS. Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA. 2014;311:2518–2531.

Arnold N, Sohn M, Maynard C, DM H. VIREC technical report 2: VA NDI mortality data merge project, 2006.

Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the department of veterans affairs. Popul Health Metrics. 2006;4:2.

Parsons L. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. In SAS SUGI 26, Paper; 2001:214–26.

D'Agostino R, Rubin D. Estimating and using propensity scores with partially missing data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:749–759.

Wright A, Burden AC, Paisey RB, Cull CA, Holman RR. Sulfonylurea inadequacy: efficacy of addition of insulin over 6 years in patients with type 2 diabetes in the U.K. Prospective diabetes study (UKPDS 57). Diabetes Care. 2002;25:330–336.

Shorr RI, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, Griffin MR. Incidence and risk factors for serious hypoglycemia in older persons using insulin or sulfonylureas. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1681–1686.

Pugh JA, Wagner ML, Sawyer J, Ramirez G, Tuley M, Friedberg SJ. Is combination sulfonylurea and insulin therapy useful in niddm patients? A metaanalysis. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:953–959.

Alvarsson M, Sundkvist G, Lager I, Berntorp K, Fernqvist-Forbes E, Steen L, Orn T, Holberg MA, Kirksaether N, Grill V. Effects of insulin vs. Glibenclamide in recently diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes: a 4-year follow-up. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:421–429.

Grymonpre R, Cheang M, Fraser M, Metge C, Sitar DS. Validity of a prescription claims database to estimate medication adherence in older persons. Med Care. 2006;44:471–477.

Metge C, Grymonpre R, Dahl M, Yogendran M. Pharmaceutical use among older adults: using administrative data to examine medication-related issues. Can J Aging (La revue Canadienne du vieillissement). 2005;24(Suppl 1):81–95.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding

This project was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services, Contract No. HHSA2902010000161, as part of the Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness (DEcIDE 2) program. This work was supported in part by VA CSRD investigator initiated grant I01CX000570-01 (Roumie), Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) No. TL1TR000447-08 from the NCATS (Min), the Center for Diabetes Translation Research P30DK092986 (Elasy, Roumie) and VA Career Development Award 2-031-09S (Hung). Support for Veterans Affairs/Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service, Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center (project numbers SDR 02–237 and 98–004).

Prior Presentations

Parts of this study were presented as abstracts at the Translational Science Meeting, Washington DC, 15–18 April 2015 and at the International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Risk Management, Boston, MA, 22–26 August 2015.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 259 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Min, J.Y., Griffin, M.R., Hung, A.M. et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Insulin versus Combination Sulfonylurea and Insulin: a Cohort Study of Veterans with Type 2 Diabetes. J GEN INTERN MED 31, 638–646 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3633-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3633-2