ABSTRACT

Objective

To systematically review the literature to identify interventions that improve minority health related to colorectal cancer care.

Data sources

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane databases, from 1950 to 2010.

Study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions

Interventions in US populations eligible for colorectal cancer screening, and composed of ≥50 % racial/ethnic minorities (or that included a specific sub-analysis by race/ethnicity). All included studies were linked to an identifiable healthcare source. The three authors independently reviewed the abstracts of all the articles and a final list was determined by consensus. All papers were independently reviewed and quality scores were calculated and assigned using the Downs and Black checklist.

Results

Thirty-three studies were included in our final analysis. Patient education involving phone or in-person contact combined with navigation can lead to modest improvements, on the order of 15 percentage points, in colorectal cancer screening rates in minority populations. Provider-directed multi-modal interventions composed of education sessions and reminders, as well as pure educational interventions were found to be effective in raising colorectal cancer screening rates, also on the order of 10 to 15 percentage points. No relevant interventions focusing on post-screening follow up, treatment adherence and survivorship were identified.

Limitations

This review excluded any intervention studies that were not tied to an identifiable healthcare source. The minority populations in most studies reviewed were predominantly Hispanic and African American, limiting generalizability to other ethnic and minority populations.

Conclusions and implications of key findings

Tailored patient education combined with patient navigation services, and physician training in communicating with patients of low health literacy, can modestly improve adherence to CRC screening. The onus is now on researchers to continue to evaluate and refine these interventions and begin to expand them to the entire colon cancer care continuum.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC), although a preventable disease, causes the death of more than 50,000 Americans per year.1 Given the ability to detect and intervene on pre-cancerous lesions, colorectal cancer screening is associated with decreased CRC mortality.2 Because of advances in screening and treatment, the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer have been declining over the last 25 years.1 Unfortunately, this decline has not been shared equally by all groups, resulting in a growing racial and ethnic survival gap over that same 25-year period.1 , 3 , 4

Racial and ethnic minority patients, as well as those with lower incomes and inadequate insurance, are less likely to receive adequate screening.5 – 7 Once screened positive, they are less likely to be treated, and once treated, less likely to have guideline recommended follow up.8 – 10

A variety of physician, patient, and health systems barriers have played their role in these disparities.11 Emerging in the last 10 to 15 years is a body of literature that focuses on investigating interventions to address these barriers. The goals of this paper are: to systematically review the medical literature for interventions conducted within health care systems that have the potential to decrease racial and ethnic disparities in the care of colorectal cancer; to evaluate the strength of their evidence; and to recommend both public health and research strategies going forward based on this evidence.

METHODS

In consultation with a biomedical librarian, an electronic search was conducted using the MEDLINE database for articles reporting on interventions that have the potential to reduce disparities in health outcomes or health care processes in colorectal cancer screening, treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life care published from 1950 to September, 2010. For the topic of colorectal cancer screening, an additional parallel search was conducted using the PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials databases. In addition, a manual search was conducted that included topic relevant review articles;12 – 15 reference lists obtained from the studies meeting pre-specified inclusion criteria; and unpublished abstracts presented in 2009 and 2010 from selected national meetings of professional societies including Digestive Diseases Week (DDW) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). This review conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards.16 A summary of the review protocol may be found in the introductory article by Chin et. al.

Search Strategy

The MEDLINE database was searched using pre-specified Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords to identify studies evaluating interventions in colorectal cancer screening, treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life care among racial and ethnic minority patients. Please see Text Box 1 for the colorectal cancer screening MEDLINE database search strategy. A full listing of the MeSH terms and Keywords used in the MEDLINE database search may be found in Appendix 1 (available online). A full listing of the search terms used in the PsycINFO and CINAHL database searches may be found in Appendix 2 (available online).

Text Box 1 Medline Colorectal Cancer Screening Intervention Search Strategy

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles and abstracts were assessed for inclusion based on pre-specified criteria. Study populations were required to be composed of patient groups with greater than 50 % minority representation (defined as >50 % racial/ethnic minority patients) or, if less than 50 %, the study must include subgroup analysis by race or ethnicity with documentation of sufficient statistical power. Articles must report on an experimental intervention (purely descriptive studies were excluded). Articles were not excluded based solely on the type of experimental study design or measured outcome. Study interventions were required to take place within the context of a consistent source of health care (community interventions must directly integrate a system of ongoing medical care). Lastly, studies were required to be conducted in the United States and to be published in English.

Data Collection Process

The titles and abstracts of articles obtained from the electronic search were screened by two reviewers (KN and JW) independently to eliminate duplicates and articles unrelated to colorectal cancer. A full text review was performed on the remaining articles to assess inclusion and exclusion criteria, discrepancies were resolved by consensus among all three reviewers. A manual reference review was performed on all articles meeting inclusion criteria and on topic relevant reviews12 – 15 in order to include articles not identified in the electronic database search. All articles not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded. Articles were then manually extracted for data including reference citation, type of intervention, study design, study population, setting, outcomes assessed, results, and quality assessment measures.

Quality Assessment

To assess study quality, each article was abstracted by two authors and assigned a quality score using a modified Downs and Black scoring algorithm. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using four randomly selected articles resulting in a weighted kappa statistic of 81.25 %. The Downs and Black checklist is a validated instrument used to assess the methodological quality of studies across a variety of domains including: reporting, external validity, bias, confounding, and power.17 For this review, we utilized a modified Downs and Black scoring checklist with a maximum achievable score of 29. To aid in the comparison of study quality across articles, a qualitative categorization grouping articles by Downs and Black score (≥20: very good; 15-19: good; 11-14: fair; ≤10: poor) was used.18

RESULTS

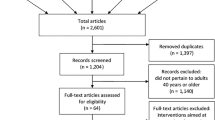

Article Selection (Figure 1)

The combined electronic database search resulted in 489 articles. A manual title and abstract review was performed, identifying 53 articles for independent full text review. Fourteen articles, representing studies of community interventions, were excluded from the review due to lack of a consistent source of healthcare (Appendix 3); 22 other studies also did not meet the pre-specified inclusion criteria. The combined electronic database search resulted in 17 articles for data collection. A manual reference review of included studies and relevant topic review articles resulted in an additional 16 articles. Overall, the search process resulted in a total of 33 articles that were included in the final systematic review. Downs and Black (DB) scores ranged from 5 to 27, with a median score of 20. The manual review of unpublished abstracts presented at selected national meetings resulted in the identification of three abstracts. There was insufficient data presented in the abstracts to perform quality assessment (Appendix 4-available online).

Demographics (Figure 2)

Figure 2 provides a breakdown of the studies by the predominant racial or ethnic population that was analyzed. Thirteen of the 33 studies included a majority of African-Americans, eight of the 33 included a majority of Hispanics, and two of the 33 included a majority of Asians. In seven of the 33 included studies the majority of the subjects were composed of a mix of racial/ethnic minorities and in three of the 33 studies a majority of the subjects was listed as “non-white”.

Intervention Type (Table 1, Figure 3)

Displayed in Table 1, are the 33 studies we included in the final analysis, as well as information related to study design, measured outcome(s), intervention details, setting, sample size and ethnicity, length of follow up, major findings, and DB score. For the purpose of further discussion and data analysis, the articles were grouped into one of three major intervention types: patient-level interventions (including education and other interventions), patient-level navigation, and provider/system-level interventions based on the predominant intervention evaluated in the study. Sixteen of 33 (48.5 %) articles included interventions that targeted CRC disparities across multiple levels (patient, provider, and/or system). Figure 3 provides a graphic description of this information, including a breakdown of the studies by the predominant intervention type, as well as the number of multi-level intervention studies.

Patient-Level Interventions (Table 1), n = 13 (39.4 %)

Intervention

Of the thirteen articles evaluating non-navigation related patient-level interventions, ten studies assessed educational interventions; Five evaluated education administered by trained professionals (telephone, one-on-one, and/or group presentation),19 – 23 and five assessed self-administered media interventions (computer, brochure, and/or video).19 , 21 – 24 Two studies evaluated FOBT distribution interventions, one through the mailing of FOBT kits25 and the other through a point of care intervention at the time of influenza vaccination.26 Three studies27 – 29 evaluated multilingual interventions consisting of community health advisors, tailored bilingual educational materials, or interpreter services.

Quality

Ten of the 13 patient-level intervention articles were randomized controlled trials,19 , 21 , 24 – 27 , 29 – 32 two were cohort studies,23 , 28 and one was a pre-test/post-test design.22 DB scores ranged from 10–26 with a median score of 22.

Screening Completion Outcomes

Eleven of the patient-level intervention articles measured completion of CRC screening as a primary outcome. Six of the studies assessed CRC screening through fecal occult blood test (FOBT) exclusively.20 , 21 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 32 The five remaining studies assessed completion of any CRC screening test modality.19 , 26 , 29 – 31

Three RCT studies19 , 21 , 24 assessing educational media interventions did not achieve significant increases in their CRC screening outcomes. Conversely, all five27 , 29 – 32 articles assessing educational interventions administered through direct contact by trained professionals achieved significant improvements in CRC screening completion, with an absolute improvement ranging from 11 % to 41.9 % (median improvement of 15 %).

Two articles examined interventions related to FOBT distribution. Goldberg et al.25 found that in a sample of predominately African American patients, mailing FOBT kits along with a standard clinic appointment reminder letter two weeks prior to the scheduled appointment, resulted in 16-fold (95 % CI 3.5, 71.4) greater odds of FOBT return at the index appointment and 13-fold (95 % CI 3.6, 45.5) greater odds of FOBT return by one year compared to usual care. Potter et al. found that in a sample of predominately Asian and Hispanic/Latino patients, providing FOBT kits and education during annual influenza vaccination appointments increased FOBT completion rates by 29.8 % (p < 0.001) compared to a 4.4 % (p = 0.07) increase in the usual care group.26

Two of the three articles evaluating multilingual interventions reported increases in CRC screening outcomes. In the study by Jacobs et al., providing professional interpreter services to selected outpatient clinics in a Spanish and Portuguese speaking population did not significantly increase the rates of FOBT completion over a two year interval, p = 0.28.28 Conversely, Tu et al. found that the odds of FOBT completion were 5.9 (95 % CI 3.25, 10.75) fold greater in Chinese Americans who received an educational intervention provided by a trilingual health educator.27 While, Walsh et al. reported that addition of a bilingual brochure with counseling by community health advisors increased the odds of self-reported FOBT screening by 3.02 (95 % CI 1.77, 5.14) compared to usual care in a predominately Hispanic/Latino and Asian patient sample.

Patient Navigator Interventions (Table 1) n = 7 (21.2 %)

Intervention

All of the navigator models included, at the minimum: repeat phone calls to patients to aid with scheduling, bowel preparation instructions, and appointment reminders. Four of the studies included more expansive services such as assistance with transportation, translation services, and referral to other social services if needed,33 – 36 and two included face-to-face meetings with participants, including accompanying to endoscopy visits if needed.33 , 36 One trial provided assistance to facilitate patient-physician communication34 through the use of patient activation cards.

Quality

Five of the seven studies were randomized controlled trials (RCT),34 – 38 one was a pre-test/post-test design39 and one was an observational cohort study.33 The DB scores ranged from 16-27 with a median of 22. Five had DB scores in the very good range and the remaining two had scores in the good range.

Screening Completion Outcomes

Excluding the observational cohort study, four studies achieved significant screening completion results with the intervention,34 , 36 , 38 , 39 and two did not.35 , 37 In those studies with a comparator arm,34 , 36 , 38 absolute improvement in endoscopy screening completion among the navigated group ranged from 7 % to 40 % with a median improvement of 16 %.

One study provided pre-planned subgroup analyses.33 In the cohort study by Chen, et al., Hispanic patients were more likely to complete screening compared to African American patients (HR 1.67;95 %CI:1.1–2.5).

Process Outcomes

Four studies specifically reported patient willingness to participate in a navigator intervention and in these studies, 44 % to 74 % agreed to navigation services with a median of 72 % agreeing to participate.33 , 34 , 36 , 38 Patient navigation also reduced the rates of broken appointments anywhere from 12 % to 62 %.33 , 37 , 39 In terms of types of services provided by navigators, in the study by Percac-Lima and colleagues, logistical barriers were identified for 60 % of patients (scheduling, bowel preparation, transportation, etc) and an intervention was performed for 65 % of these barriers.36

Other Outcomes

In the study by Chen et al., 66 % of patients reported they definitely or probably would not have completed their colonoscopy without the navigator.33 In the randomized trial by Christie and colleagues, 63 % of non-navigated patients refused colonoscopy compared to 23 % in navigated group and 77 % of navigated patients reported they would refer family or friends for colonoscopy.

Provider/ System Level Interventions (Table 1), n = 13 (39.4 %)

Intervention

The interventions tested in these studies were predominantly multi-modal, however, all but two included an educational component.40 , 41 Seven of the studies included an educational component that focused on didactic sessions stressing standard national guidelines for CRC screening and the importance of screening.20 , 42 – 47 The sessions varied widely in style, number and length. Two studies focused on training providers in communication skills targeting low-income/low-literacy patients.46 , 48 Three studies utilized individual and/or group feedback sessions.48 – 50 Four studies used a provider reminder intervention.43 , 47 , 49 , 50 Two studies evaluated interventions that aimed to improve clinic flow.47 , 49

Quality

Of these 13 studies, six utilized a pre-test/post-test design,20 , 42 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 50 , 51 five were randomized controlled trials,47 , 48 and two were cohort studies.40 , 41 The DB scores ranged from 5–25 with a median of 19. Ten of the studies had DB scores within the good or very good range,40 , 41 , 43 – 50 two were fair,20 , 42 and one was poor.51

Screening Completion Outcomes Measures

The primary endpoint for 11 of the 13 included studies was completion of CRC screening. Six of the studies with DB scores in the “very good” or “good” range achieved a significant increase in screening completion results with the intervention43 , 44 , 46 , 48 – 50 and two did not.40 , 47 In those studies with a comparator arm (n = 4), absolute improvement in CRC screening completion among the intervention group ranged from 4.2 % to 16 % (median 8.9 %).44 , 48 , 49 In those studies with a pre-test/post-test design (n = 6), the absolute improvement in CRC screening completion in the post-intervention setting ranged from 12.3 % to 55.8 % (median 17.7 %).20 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 50 , 51 In the randomized study by Ferreira and colleagues48 which measured the effect of didactic educational sessions (aimed at communicating with patients with low literacy) on CRC screening completion, the effect was particularly pronounced in patients with health literacy skills less than the ninth grade level (55.7 % FOBT completion in the intervention arm vs. 30 % of the controls, p < 0.01). Similarly in the pre-test/post-test study by Khankari et al.,46 which focused on communication strategies for physicians of patients with lower health literacy as well as physician feedback and reminder systems, the CRC screening rate increased from 11.5 % to 27.9 % (p < 0.001).

Process Outcomes Measures

Two studies included process outcomes: physician recommendation of CRC screening.46 , 48 Ferreira reports that the recommendation rate was 76 % in the intervention arm compared to 69.4 % in the control arm (p = 0.02)48 and Khankari reports that physician recommendation increased from 31.6 % in the pre-intervention setting to 92.9 % in the post-intervention setting (p < 0.001).46

Knowledge Outcomes Measures

The study by Sheinfeld–Gorin45 measured the effect of repeated one on one physician education didactic sessions. Following the educational sessions, the physicians in the intervention arm completed a questionnaire and were able to correctly identify more barriers to CRC screening (5.35 vs. 4.73, p < 0.05) and an increased knowledge of cancer screening guidelines (2.26 vs. 5.9, p < 0.0001) compared to the pre-test setting.

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review resulted in the identification of 33 articles that reported on interventions to improve CRC screening in minority populations. We were unable to identify any articles that tested interventions to reduce disparities in post-screening follow-up, CRC treatment, survivorship, or end-of-life care. Therefore, a significant portion of the cancer care continuum remains neglected in the published literature on how to improve colorectal cancer care for racial and ethnic minorities. The absence of studies aimed at increasing initiation and adherence to treatment or follow up after treatment is unfortunate given that prior work has shown that there are clear racial and ethnic differences in stage-specific colorectal cancer survival and in treatment and follow up after treatment.3 , 4 , 8 , 9 Moreover, there is evidence from both clinical trials and equal access systems such as the Department of Defense that when treatment and follow up are equal, racial and ethnic disparities in survival disappear.52 , 53

The dominant CRC screening promotion interventions tested to date are patient education and navigation. The heterogeneity across the targeted population, intervention, and measured outcome makes the identification of essential intervention characteristics difficult. However, a common theme related to the intensity of patient contact did emerge. Patient education interventions that did not successfully increase screening rates included an 8-minute video and pamphlet, computer-assisted instruction, and a video instrument that due to “poor video quality” and “technical difficulties” was rendered ineffectual in its objective. Comparatively, in a study that used telephone outreach and education, CRC screening increased by more than four-fold.30 In patient education studies without direct patient contact, the use of culturally tailored printed materials appeared superior to standard materials.31 For patient navigation services, even the most basic model appeared to be successful in improving completion of colorectal cancer screening rates on the order of 15 %.

In short, the data suggests that patient education involving phone or in-person contact combined with navigation through at least the basic steps of the colon cancer screening process (appointment set up, bowel preparation, appointment reminder) can lead to modest improvements in colorectal cancer screening rates among the minority populations tested. The more difficult question is how to implement these intensive interventions on a system-wide scale. In two studies which reported the time resources involved, approximately 3–5 phone calls were required for each patient and initial phone calls lasted roughly 20 minutes with subsequent calls lasting about 15 minutes; thus, roughly 1-1.5 hours of staff time were spent per patient.30 , 34 In another study involving 352 patients, two case managers made 14,978 calls over 3 years of the trial and responded to 780 requests for services.35 Hiring the personnel to do this in every clinical setting will likely be cost-prohibitive and some type of centralization of services will be needed to achieve economies of scale. In addition, it is imperative that this type of service be reimbursed if it is ever going to take hold. We believe the next generation of studies should focus on implementation logistics of such an approach in a system-wide setting.

The results of studies targeting providers or clinic systems suggest that provider-directed educational interventions are effective in increasing CRC screening rates on the order of 10-15 percentage points. The strongest evidence from these studies involved the training of physicians to communicate with patients of low health literacy.46 , 48 System process improvements such as physician reminder systems and check lists were also successful; however, an important caveat is that most of these studies were performed in a single institution or clinic. The use of these systems in a large community health center network was less successful.47 The next generation of studies need to focus on both the implementation logistics of this type of approach in large health care systems rather than in the controlled setting of small clinics and must include long-term follow to determine the durability and sustainability of this type of approach.

There are several limitations inherent in this type of systematic review of the literature. Certainly publication bias of positive results remains foremost. Because our review and search terms were limited to interventions targeting underserved racial and ethnic minority patients, we found that many articles, (subsequently discovered during reference reviews), included these populations but were not so classified in the MESH headings or key word searches. We have taken all efforts to ensure that all relevant articles are included in this review, but cannot exclude the possibility of missing articles. Since many of the studies focused only on minority patients rather than on comparisons with white patients, we cannot conclude that these interventions would truly reduce the growing disparity gap in colon cancer care. The minority populations in these studies were predominantly Hispanic and African American, thereby limiting generalizing findings across other minorities, such as Asian and Pacific Islander populations. Finally, the specified criteria for this review excluded purely public health campaigns such as targeted advertising to at-risk populations and community-based interventions, such as education provided in churches or at health fairs, if there was no documented link to a specific health care clinic or system (see Appendix 3 for a listing of these studies-available online).

The field of cancer health disparities has matured over the last decade, and we can now point to well designed and implemented studies that are not satisfied with simply pointing out disparities, but rather have focused on ways to eliminate them. The studies included in this systematic review provide a good foundation of evidence that tailored patient education ideally involving personal contact combined with patient navigation services to overcome logistical barriers to screening, and physician training in more effectively communicating with patients of low health literacy, can modestly improve adherence to CRC screening. The onus is now on researchers to continue to evaluate and refine these interventions and begin to expand them to the entire colon cancer care continuum.

REFERENCES

Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300.

Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(19):1365–71.

Ayanian JZ. Racial disparities in outcomes of colorectal cancer screening: biology or barriers to optimal care? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(8):511–3.

Surveillance E, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 17 Regs Limited-Use + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2007 Sub (1973-2005 varying), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2008, based on the November 2007 submission. , Formats: A.

Cooper GS, Koroukian SM. Racial disparities in the use of and indications for colorectal procedures in Medicare beneficiaries. Cancer. 2004;100(2):418–24.

Etzioni DA, Ponce NA, Babey SH, Spencer BA, Brown ER, Ko CY, et al. A population-based study of colorectal cancer test use: results from the 2001 California Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2523–32.

Nadel MR, Berkowitz Z, Klabunde CN, Smith RA, Coughlin SS, White MC. Fecal occult blood testing beliefs and practices of U.S. primary care physicians: serious deviations from evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):833–9. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1328-7.

Baldwin LM, Dobie SA, Billingsley K, Cai Y, Wright GE, Dominitz JA, et al. Explaining black-white differences in receipt of recommended colon cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(16):1211–20.

Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Chak A, Rimm AA. Patterns of endoscopic follow-up after surgery for nonmetastatic colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(1):33–8.

Ellison GL, Warren JL, Knopf KB, Brown ML. Racial differences in the receipt of bowel surveillance following potentially curative colorectal cancer surgery. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 2):1885–903.

Allen JD, Barlow WE, Duncan RP, Egede LE, Friedman LS, Keating NL, et al. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Enhancing Use and Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening. NIH Consens State Sci Statement. 2010;27(1).

Holden DJ, Jonas DE, Porterfield DS, Reuland D, Harris R. Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(10):668–76.

Morrow JB, Dallo FJ, Julka M. Community-based colorectal cancer screening trials with multi-ethnic groups: a systematic review. J Community Health.35(6):592-601. doi:10.1007/s10900-010-9247-4

Powe BD, Faulkenberry R, Harmond L. A review of intervention studies that seek to increase colorectal cancer screening among African-Americans. Am J Health Promot.25(2):92-9. doi:10.4278/ajhp.080826-LIT-162

Vernon SW. Participation in colorectal cancer screening: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(19):1406–22.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):101S–56S.

Fitzgibbon ML, Ferreira MR, Dolan NC, Davis TC, Rademaker AW, Wolf MS, et al. Process evaluation in an intervention designed to improve rates of colorectal cancer screening in a VA medical center. Health Promot Pract. 2007;8(3):273–81.

Friedman M, Borum ML, Friedman M, Borum ML. Colorectal cancer screening of African Americans by internal medicine resident physicians can be improved with focused educational efforts. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1010–2.

Miller DP Jr, Kimberly JR Jr, Case LD, Wofford JL. Using a computer to teach patients about fecal occult blood screening. A randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):984–8.

Makoul G, Cameron KA, Baker DW, Francis L, Scholtens D, Wolf MS. A multimedia patient education program on colorectal cancer screening increases knowledge and willingness to consider screening among Hispanic/Latino patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(2):220–6.

Hoffman A, Abcarian H. Six years of occult blood screening in an urban public hospital: concepts, methods, and reflections on approaches to reducing avoidable mortality among black Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 1991;83(11):994–9.

Friedman LC, Everett TE, Peterson L, Ogbonnaya KI, Mendizabal V. Compliance with fecal occult blood test screening among low-income medical outpatients: a randomized controlled trial using a videotaped intervention. J Cancer Educ. 2001;16(2):85–8.

Goldberg D, Schiff GD, McNutt R, Furumoto-Dawson A, Hammerman M, Hoffman A. Mailings timed to patients' appointments: a controlled trial of fecal occult blood test cards. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(5):431–5.

Potter MB, Phengrasamy L, Hudes ES, McPhee SJ, Walsh JM. Offering annual fecal occult blood tests at annual flu shot clinics increases colorectal cancer screening rates. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):17–23.

Tu SP, Taylor V, Yasui Y, Chun A, Yip MP, Acorda E, et al. Promoting culturally appropriate colorectal cancer screening through a health educator: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2006;107(5):959–66.

Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-English-proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):468–74.

Walsh JME, Salazar R, Nguyen TT, Kaplan C, Nguyen L, Hwang J, et al. Healthy colon, healthy life: a novel colorectal cancer screening intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(1):1–14. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.020.

Basch CE, Wolf RL, Brouse CH, Shmukler C, Neugut A, DeCarlo LT, et al. Telephone outreach to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban minority population. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2246–53.

Myers RE, Sifri R, Hyslop T, Rosenthal M, Vernon SW, Cocroft J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer. 2007;110(9):2083–91. doi:10.1002/cncr.23022.

Stokamer CL, Tenner CT, Chaudhuri J, Vazquez E, Bini EJ. Randomized controlled trial of the impact of intensive patient education on compliance with fecal occult blood testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(3):278–82.

Chen LA, Santos S, Jandorf L, Christie J, Castillo A, Winkel G, et al. A program to enhance completion of screening colonoscopy among urban minorities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(4):443–50.

Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Robinson CM, Greene MA, Sox CH, et al. Telephone care management to improve cancer screening among low-income women: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):563–71.

Ford ME, Havstad S, Vernon SW, Davis SD, Kroll D, Lamerato L, et al. Enhancing adherence among older African American men enrolled in a longitudinal cancer screening trial. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):545–50.

Percac-Lima S, Grant RW, Green AR, Ashburner JM, Gamba G, Oo S, et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):211–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0864-x.

Christie J, Itzkowitz S, Lihau-Nkanza I, Castillo A, Redd W, Jandorf L, et al. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(3):278–84.

Jandorf L, Gutierrez Y, Lopez J, Christie J, Itzkowitz SH, Jandorf L, et al. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):216–24.

Nash D, Azeez S, Vlahov D, Schori M. Evaluation of an intervention to increase screening colonoscopy in an urban public hospital setting. J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):231–43. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9029-6.

Armour BS, Friedman C, Pitts MM, Wike J, Alley L, Etchason J. The influence of year-end bonuses on colorectal cancer screening. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(9):617–24.

Parikh A, Ramamoorthy R, Kim KH, Holland BK, Houghton J. Fecal occult blood testing in a noncompliant inner city minority population: increased compliance and adherence to screening procedures without loss of test sensitivity using stool obtained at the time of in-office rectal examination. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(6):1908–13.

Zubarik R, Eisen G, Zubarik J, Teal C, Benjamin S, Glaser M, et al. Education improves colorectal cancer screening by flexible sigmoidoscopy in an inner city population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(2):509–12.

Struewing JP, Pape DM, Snow DA. Improving colorectal cancer screening in a medical residents' primary care clinic. Am J Prev Med. 1991;7(2):75–81.

Lane DS, Messina CR, Cavanagh MF, Chen JJ. A provider intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in county health centers. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S109–16.

Sheinfeld Gorin S, Gemson D, Ashford A, Bloch S, Lantigua R, Ahsan H, et al. Cancer education among primary care physicians in an underserved community. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(1):53–8.

Khankari K, Eder M, Osborn CY, Makoul G, Clayman M, Skripkauskas S, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening among the medically underserved: a pilot study within a federally qualified health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(10):1410–4.

Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Sox CH, Cassels AN, Negron F, Younge RG, et al. Cancer early-detection services in community health centers for the underserved. A randomized controlled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(4):320–7. discussion 8.

Ferreira MR, Dolan NC, Fitzgibbon ML, Davis TC, Gorby N, Ladewski L, et al. Health care provider-directed intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among veterans: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1548–54.

Roetzheim RG, Christman LK, Jacobsen PB, Cantor AB, Schroeder J, Abdulla R, et al. A randomized controlled trial to increase cancer screening among attendees of community health centers. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(4):294–300.

McPhee SJ, Bird JA, Jenkins CN, Fordham D. Promoting cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial of three interventions. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(8):1866–72.

Lloyd SC, Harvey NR, Hebert JR, Daguise V, Williams D, Scott DB, et al. Racial disparities in colon cancer. Primary care endoscopy as a tool to increase screening rates among minority patients. [Erratum appears in Cancer. 2007 May 15;109(10):2154]. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):378–85.

Albain KS, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA Jr, Hershman DL. Racial disparities in cancer survival among randomized clinical trials patients of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(14):984–92.

Hofmann LJ, Lee S, Waddell B, Davis KG. Effect of race on colon cancer treatment and outcomes in the Department of Defense healthcare system. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(1):9–15.

Blumenthal DS, Smith SA, Majett CD, Alema-Mensah E. A trial of 3 interventions to promote colorectal cancer screening in African Americans. Cancer. 2010;116(4):922–9. doi:10.1002/cncr.24842.

Campbell MK, James A, Hudson MA, Carr C, Jackson E, Oakes V, et al. Improving multiple behaviors for colorectal cancer prevention among African American church members. Heal Psychol. 2004;23(5):492–502.

Weinrich SP, Weinrich MC, Stromborg MF, Boyd MD, Weiss HL. Using elderly educators to increase colorectal cancer screening. Gerontologist. 1993;33(4):491–6.

Larkey LK, Lopez AM, Minnal A, Gonzalez J, Larkey LK, Lopez AM, et al. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer screening among underserved Latina women: a randomized pilot study. Cancer Control. 2009;16(1):79–87.

Powe BD, Weinrich S. An intervention to decrease cancer fatalism among rural elders. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26(3):583–8.

Weinrich SP, Weinrich MC, Boyd MD, Atwood J, Cervenka B. Teaching older adults by adapting for aging changes. Cancer Nurs. 1994;17(6):494–500.

Morgan PD, Fogel J, Tyler ID, Jones JR. Culturally targeted educational intervention to increase colorectal health awareness among African Americans. J Health Care Poor & Underserved.21(3):132-47.

Powe BD, Ntekop E, Barron M, Powe BD, Ntekop E, Barron M. An intervention study to increase colorectal cancer knowledge and screening among community elders. Public Health Nurs. 2004;21(5):435–42.

Powe BD, Powe BD. Promoting fecal occult blood testing in rural African American women. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(3):139–46.

Blumenthal DS, Fort JG, Ahmed NU, Semenya KA, Schreiber GB, Perry S, et al. Impact of a two-city community cancer prevention intervention on African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(11):1479–88.

Braun KL, Fong M, Kaanoi ME, Kamaka ML, Gotay CC, Braun KL, et al. Testing a culturally appropriate, theory-based intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening among Native Hawaiians. Prev Med. 2005;40(6):619–27.

Larkey L, Larkey L. Las mujeres saludables: reaching Latinas for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer prevention and screening. J Community Health. 2006;31(1):69–77.

Wu T, Kao JY, Hsieh H, Tang Y, Chen J, Lee J, et al. Effective colorectal cancer education for Asian Americans: a Michigan program. J Cancer Educ. 25(2):146–52. doi:10.1007/s13187-009-0009-x

Mitchell-Beren ME, Dodds ME, Choi KL, Waskerwitz TR. A colorectal cancer prevention, screening, and evaluation program in community black churches. CA Cancer J Clin. 1989;39(2):115–8.

Acknowledgments

We thank Toni Cipriano for her careful review of this manuscript.

Funding Source

Support for this publication was provided by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program.

Prior Presentations

None.

Conflict of Interest

Keith Naylor and James Ward declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Blase Polite provides consulting to Quintiles Consulting Group and, Roche-Genentech

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Systematic review registration number

This systematic review is not registered.

K. Naylor and J. Ward contributed equally to the manuscript

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 101 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Naylor, K., Ward, J. & Polite, B.N. Interventions to Improve Care Related to Colorectal Cancer Among Racial and Ethnic Minorities: A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 27, 1033–1046 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2