BACKGROUND

Compared to those with depression alone, depressed patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) experience more severe psychiatric symptomatology and factors that complicate treatment.

OBJECTIVE

To estimate PTSD prevalence among depressed military veteran primary care patients and compare demographic/illness characteristics of PTSD screen-positive depressed patients (MDD-PTSD+) to those with depression alone (MDD).

DESIGN

Cross-sectional comparison of MDD patients versus MDD-PTSD+ patients.

PARTICIPANTS

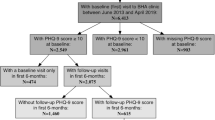

Six hundred seventy-seven randomly sampled depressed patients with at least 1 primary care visit in the previous 12 months. Participants composed the baseline sample of a group randomized trial of collaborative care for depression in 10 VA primary care practices in 5 states.

MEASUREMENTS

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 assessed MDD. Probable PTSD was defined as a Primary Care PTSD Screen ≥ 3. Regression-based techniques compared MDD and MDD-PTSD+ patients on demographic/illness characteristics.

RESULTS

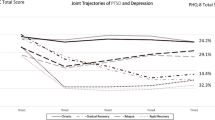

Thirty-six percent of depressed patients screened positive for PTSD. Adjusting for sociodemographic differences and physical illness comorbidity, MDD-PTSD+ patients reported more severe depression (P < .001), lower social support (P < .001), more frequent outpatient health care visits (P < .001), and were more likely to report suicidal ideation (P < .001) than MDD patients. No differences were observed in alcohol consumption, self-reported general health, and physical illness comorbidity.

CONCLUSIONS

PTSD is more common among depressed primary care patients than previously thought. Comorbid PTSD among depressed patients is associated with increased illness burden, poorer prognosis, and delayed response to depression treatment. Providers should consider recommending psychotherapeutic interventions for depressed patients with PTSD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, Smith J, Coyne J, Smith GR. Persistently poor outcomes of undetected major depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psych. 1998;20:12–20.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Barlow W. Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. Gen Hosp Psych. 1993;15:399–408.

Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psych. 1992;14:237–47.

Olfson M, Shea S, Feder A, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:876–83.

Wells KB, Hays RD, Burnam A, et al. Detection of depressive disorder for patients receiving prepaid or fee-for-service care: results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1989;262:3298–303.

Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus H. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA. 2002;287:203–9.

Depression Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guideline number 5: depression in primary care, volumes 1 & 2. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. AHCPR Publications 93-0550-51.

American Psychiatric Association Workgroup on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, 2nd edition. Washington: 2000; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Website: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/Depression2e.book.cfm.

The Management of Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Veterans Health Administration/Department of Defense clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. Version 2.0, February 2000, Washington DC.

Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds III CF, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–91.

Katon W, Rutter C, Ludman EJ, et al. A randomized trial of relapse prevention of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:241–7.

Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. NEJM. 2000;343:1942–50.

Rollman BL, Weinreb L, Korsen N, Schulberg HC. Implementation of guideline-based care for depression in primary care. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:43–53.

Cabana MD, Rushton JL, Rush AJ. Implementing practice guidelines for depression: Applying a new framework to an old problem. Gen Hosp Psych. 2002;24:35–42.

Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Gen Hosp Psych. 2005;27:169–79.

Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, et al. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in female Veterans Affairs patients. Gen Hosp Psych. 2002;24:367–74.

Hankin CS, Spiro III A, Miller DR, Kazis L. Mental disorders and mental health treatment among US Department of Veterans Affairs outpatients: the Veterans Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1924–30.

Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psych. 2000;22:261–9.

Taubman-Ben-Ari O, Rabinowitz J, Feldman D, Vaturi R. Post-traumatic stress disorder in primary-care settings: prevalence and physician’s detection. Psychol Med. 2001;31:555–60.

Davidson JRT, Hughes D, Blazer DG, George LK. Post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med. 1991;21:713–21.

Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, et al. PTSD symptoms, demographic characteristics, and functional status among veterans treated in VA primary care clinics. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:293–301.

Nixon RDV, Resick PA, Nishith P. An exploration of comorbid depression among female victims of intimate partner violence with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:315–20.

Blanchard EB, Buckley TC, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE. Posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid major depression: Is the correlation an illusion? J Anxiety Disord. 1998;12:21–37.

Boudreaux E, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Best CL, Saunders BE. Criminal victimization, posttraumatic stress disorder, and comorbid psychopathology among a community sample of women. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11:665–78.

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–60.

Hankin CS, Spiro III A, Miller DR, Kazis L. Mental disorders and mental health treatment among US Department of Veterans Affairs outpatients: the Veterans Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1924–30.

Office of Quality and Performance. FY2005 VA Performance Measurement System Technical Manual. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2005.

Zlotnick C, Rodriquez BF, Wiesberg RB, et al. Chronicity in posttraumatic stress disorder and predictors of the course of posttraumatic stress disorder among primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:153–9.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. JGIM. 2001;16:606–13.

Nease Jr DE, Malouin JM. Depression screening: a practical strategy. J Fam Pract. 2003;52:118–26.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:327.

Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimmerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry. 2003;9:9–14.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–95.

Bradley KA, Maynard C, Kivlahan DR, et al. The relationship between alcohol screening questionnaires and mortality among male VA outpatients. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:826–33.

Kazis LE, Ren XS, Lee A, et al. Health status in VA patients: results from the Veterans Health Study. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:28–38.

Fan VS, Au D, Heagerty P, Deyo RA, McDonnell MB, Fihn SD. Validation of case-mix measures derived from self-reports of diagnoses and health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:371–80.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–14.

Meredith LS, Orland M, Humphrey N, Camp P, Sherbourne CD. Are better ratings of the patient–provider relationship associated with higher quality care for depression? Med Care. 2001;39:349–60.

Oquendo MA, Friend JM, Halberstam B, et al. Association of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression with greater risk for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:580–2.

Oquendo M, Brent DA, Birmaher B, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbid with major depression: factors mediating the association with suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:560–6.

Hegel MT, Unutzer J, Tang L, et al. Impact of comorbid panic and posttraumatic stress disorder on outcomes of collarborative care for late-life depression in primary care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:48–58.

Holtzheimer PE, Russo J, Zatzick D, Bundy C, Roy-Byrne PP. The impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder on short-term outcome in hospitalized patients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:970–6.

Lara ME, Leader J, Klein DN. The association between social support and course of depression: is it confounded with personality? J Abnorm Psychology. 1997;106:478–82.

Oslin DW, Datto CJ, Kallan MJ, Katz IR, Edell WS, TenHave T. Association between medical comorbidity and treatment outcomes in late-life depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:823–8.

Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Jones MP, et al. Risk factors for late-life suicide: a prospective, community-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:398–406.

Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, Dutra L, Westen D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:214–27.

Nishith P, Nixon RDV, Resick PA. Resolution of trauma-related guilt following treatment of PTSD in female rape victims: a result of cognitive processing therapy targeting comorbid depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;86:259–65.

Felker BL, Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, et al. Identifying depressed patients with a high risk of comorbid anxiety in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiat. 2003;5:104–10.

Gaynes BN, Magruder KM, Burns BJ, Wagner HR, Yarnall KSH, Broadhead WE. Does a coexisting anxiety disorder predict persistence of depressive illness in primary care patients with major depression? Gen Hosp Psych. 1999;21:158–67.

Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Course of depression in patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 1997;43:245–50.

Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events of different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:409–18.

Grubaugh AL, Magruder KM, Waldrop AE, Elhai JD, Knapp RG, Frueh BC. Subthreshold PTSD in primary care: prevalence, psychiatric disorders, healthcare use, and functional status. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:658–64.

Backenstrass M, Frank A, Joest K, Hingmann S, Mundt C, Kronmüller K. A comparative study of nonspecific depressive symptoms and minor depression regarding functional impairment and associated characteristics in primary care. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:35–41.

Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, et al. Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1114–9.

Herbeck Belnap B, Kuebler J, Upshur C, et al. Challenges of implementing depression care management in the primary care setting. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33:65–75.

Kilbourne AM, Rollman BL, Schulberg HC, Herbeck Belnap B, Pincus HA. A clinical framework for depression treatment in primary care. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:545–53.

Davidson JRT, Connor KM. Management of posttraumatic stress disorder: diagnostic and therapeutic issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:33–8.

Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. NEJM. 2004;351:13–22.

Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295:1023–32.

Acknowledgments

The results reported here were from the Well-Being Among Veterans Enhancement Study (WAVES). WAVES received financial support from a grant (MHI 99-375: Chaney EF & Rubenstein LV, Co-PIs) from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development (HSR& D). An HSR& D Postdoctoral Traineeship (Campbell) provided additional support. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the University of Montana, the University of Washington, the University of California Los Angeles, or the RAND Health Program. Portions of this project were presented at the Department of Veterans Affairs HSR& D National Annual Meeting (2005, February), Baltimore, MD. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Robert Petzel, MD; Kathy Henderson, MD; Scott Ober, MD; Maurilio Garcia-Maldinado, MD; Laura M. Bonner, PhD; Barbara Simon, MA; Carol Simons; and the WAVES research group.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Felkier reported receiving honoraria from Pfizer for speaking. Dr. Chaney reported receiving honorarium from The RAND Corporation for article review. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, D.G., Felker, B.L., Liu, CF. et al. Prevalence of Depression–PTSD Comorbidity: Implications for Clinical Practice Guidelines and Primary Care-based Interventions. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 711–718 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0101-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0101-4