Abstract

Despite major changes in gender divisions of work since the 1960s, women continue to perform a larger share of unpaid housework and care than men, whereas men continue to perform more paid work. This is true for a wide range of countries. The paper first describes respective macro-trends for women’s and men’s changing contributions to paid work, routine housework and child care over the past 70 years. It then focuses on the role of institutional context and individual agency in gender divisions of routine housework according to cross-national comparative research published since 2000. On the macro level, the paper identifies three main areas of investigation: the role of work–family policies, welfare state regimes, and national levels of gender equality (Gender Empowerment Measure, the Gender Development Index and the Gender Inequality Index) for men’s and women’s divisions of work. On the micro level, studies mainly assess theories of economic dependency and resource bargaining, time availability, doing gender and deviance neutralization. More recently, research is turning to the examination of inter-relations between the micro- and macro-level factors. According to the state of research, women are better able to enact economic and noneconomic agency in national contexts with high levels of gender equality and supportive work–family policies. This is apparent in the Scandinavian countries.

Zusammenfassung

Obwohl sich die geschlechtsspezifische Arbeitsteilung seit den 1960er-Jahren gewandelt hat, verrichten Frauen noch immer einen weitaus größeren Anteil an unbezahlter Hausarbeit als Männer, während Männer weiterhin mehr Erwerbsarbeit verrichten. Dieser Befund gilt für ein breites Spektrum an Ländern. In dem vorliegenden Artikel werden zunächst die zugrunde liegenden Makrotrends der veränderten Beiträge von Frauen und Männern zu Erwerbsarbeit, Routinehaushaltstätigkeiten und Kinderbetreuung in den letzten 70 Jahren beschrieben. Danach wird auf Basis der seit dem Jahr 2000 publizierten vergleichenden Forschungsergebnisse die Rolle institutioneller Kontexte und individueller Agency, d. h. individueller Handlungsspielräume, bei der Verrichtung von Hausarbeit in den Blick genommen. Auf der Makroebene werden in diesem Artikel drei Hauptforschungslinien zur Arbeitsteilung von Männern und Frauen identifiziert: die Rolle von Arbeits- und Familienpolitik, von Wohlfahrtsstaaten und von Geschlechteregalität (Gender Empowerment Measure, GEM; Gender Development Index, GII; und Gender Inequality Index, GDI). Auf der Mikroebene werden die Rolle ökonomischer Abhängigkeiten, ökonomische Verhandlungstheorien, zeitliche Verfügbarkeit, Doing Gender und Devianzneutralisierung untersucht. Aktuell richtet sich die Forschung zudem verstärkt auf Wechselwirkungen zwischen diesen Mikro- und Makrofaktoren. Der Forschungsstand zeigt, dass Frauen ökonomische und nichtökonomische Formen von Agency besser in nationalen Kontexten realisieren können, in denen ein hohes Maß an Geschlechteregalität besteht und in denen es eine unterstützende Arbeits- und Familienpolitik gibt. Beide Randbedingungen sind v. a. in den skandinavischen Ländern zu finden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This literature argues that “Conspicuous care for the home is a way of demonstrating that a family is affluent enough either to free a wife from having to work in the labor market so that she can devote time to surplus labor, or, if she does work in the labor market, to pay someone else to do the surplus labor for the family. In either case, the meticulous, upkeep of a home produced by women’s surplus labor is a marker of class, race, and ethnic distinction (…)” (Thompson and Armato 2012, p. 80).

In this paper, if not further specified, the term ‘gender divisions of work’ refers to how all types of work, paid and unpaid, are divided between men and women. This perspective includes studies of gender-change in either work sphere as well as changes among women and men. Work is defined as “sets of tasks that people carry out, often for a wage, to produce goods or services for others” (Smith 2006, p. 676). Unpaid work comprises a broad range of productive and reproductive tasks, including unpaid routine housework and unpaid child care (Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard 2010).

Although confidence in comparative designs is far from being uncontroversial (for a summary of the critique see for instance Goerres et al. 2019), cross-national comparisons allow for testing empirical evidence and interpretations thereof across contexts, thus providing additional opportunities to assess micro-level hypotheses (Kohn 1987). This aspect is salient for studying gendered divisions of labour, because this field of research has paid a lot of attention to micro-level determinants (see Sect. 4.2).

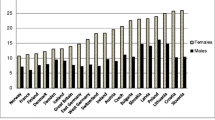

Countries have been selected to reflect the spectrum welfare state regimes discussed in the previous section, and according to the availability of time trend data.

Data for 2017 have been available only for Sweden (ratio of 90) and Spain (ratio of 82).

Of course, variance components are further influenced by other aspects of study design, such as the selection of countries, micro-level sampling frames and construction of the dependent variable.

A broad range of macro-level work–family policy indicators have become available which allow for assessing the impact of specific macro-level variables and work–family policies on gender divisions of labor (for example the OECD family data base; Multilinks Data base; various gender equality measures, developed the United Nation’s Development Programme).

Path dependencies concern established routines in everyday life as well as trajectories, such as career paths, which are unlikely to change, unless they are disrupted by biographical turning points (Nitsche and Grunow 2016). Turning points that may impact gender divisions of paid and unpaid work include the birth of children, couples’ separation, illness or job loss. The notion of linked lives emphasizes that individual life courses are tied to the life courses of other people, most importantly that of partners and children (Moen 2003).

Bühlmann et al. (2009) base their analysis on cross-sectional ESS data, but they use a life course approach to construct comparison groups reflecting different biographical stages and to inform their hypotheses.

References

Aassve, Arnstein, Giulia Fuochi, and Letizia Mencarini. 2014. Desperate housework: relative resources, time availability, economic dependency, and gender ideology across Europe. Journal of Family Issues 35:1000–1022.

Aisenbrey, Silke, Marie Evertsson, and Daniela Grunow. 2009. Is there a career penalty for mothers’ time out? A comparison of Germany, Sweden and the United States. Social Forces 88:573–605.

Alsarve, Jenny, Katarina Boye, and Christine Roman. 2019. Realized plans or revised dreams? Swedish parents’ experiences of care, parental leave and paid work after childbirth. In New parents in Europe: Work-care practices, Gender norms and Family Policies, ed. Daniela Grunow, Marie Evertsson. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Forthcoming.

Altintas, Evrim, and Oriel Sullivan. 2016. 50 years of change updated: cross-national gender convergence in housework. Demographic Research 35:455–470.

Altintas, Evrim, and Oriel Sullivan. 2017. Trends in fathers’ contribution to housework and childcare under different welfare policy regimes. Social Politics 24:81–108.

Anxo, Dominique, Letizia Mencarini, Ariane Pailhé, Anne Solaz, Maria Letizia Tanturri, and Lennart Flood. 2011. Gender differences in time use over the life course in France, Italy, Sweden, and the US. Feminist Economics 17(3):159–195.

Barnett, Rosalind C. 1994. Home-to-work spillover revisited: a study of full-time employed women in dual-earner couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family 56:647–656.

Barnett, Rosalind C., and Yu -Chu Shen. 1997. Gender, high- and low-schedule-control housework tasks, and psychological distress. A study of dual-earner couples. Journal of Family Issues 18:403–428.

Batalova, Jeanne A., and Philip N. Cohen. 2002. Premarital cohabitation and housework: couples in cross-national perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family 64:743–755.

Baxter, Janeen, and Tsui Tai. 2016. Inequalities in unpaid work: a cross-national comparison. In Handbook on well-being of working women. International handbooks of quality-of-life, ed. Mary L. Connerley, Jiyun Wu, 653–671. Dordrecht: Springer.

Baxter, Janeen, Sandra Buchler, Francisco Perales, and Mark Western. 2014. A life-changing event: first births and men’s and women’s attitudes to mothering and gender divisions of labor. Social Forces 93:989–1014.

Becker, Gary S. 1981. A treatise on the family. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press.

Berk, Sarah F. 1985. The gender factory: the apportionment of work in American households. New York: Plenum Press.

Bianchi, Suzanne M., Liana C. Sayer, Melissa A. Milkie, and John P. Robinson. 2012. Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces 91:55–63.

Bittman, Michael, Paula England, Liana C. Sayer, Nancy Folbre, and George Matheson. 2003. When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology 109:186–214.

Bloemen, Hans G., and Elena G.F. Stancanelli. 2014. Market hours, household work, childcare, and wage rates of partners: an empirical analysis. Review of Economics of the Household 12:51–81.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, Erik Klijzing, Melinda Mills, and Karin Kurz. 2005. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society: the losers in a globalizing world. London: Routledge.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, Jan Skopek, Moris Triventi, and Sandra Buchholz. 2015. Gender, education and employment: an international comparison of school-to-work transitions. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Boeckmann, Irene, and Michelle Budig. 2013. Fatherhood, intra-household employment dynamics, and men’s earnings in a cross-national perspective (No. 592). LIS Working Paper Series. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/95618. Accessed 8 June 2018.

Bonke, Jens. 2005. Paid work and unpaid work: diary information versus questionnaire information. Social Indicators Research 70:349–368.

Brückner, Hannah, and Karl Ulrich Mayer. 2005. De-standardization of the life course: what it might mean? And if it means anything, whether it actually took place? Advances in Life Course Research 9:27–53.

Budig, Michelle J. 2004. Feminism and the family. In The Blackwell companion to the sociology of families, ed. Jacqueline Scott, Judith Treas, and Martin Richards, 416–434. Oxford: Blackwell.

Budig, Michelle J., Joya Misra, and Irene Boeckmann. 2012. The motherhood penalty in cross-national perspective: the importance of work–family policies and cultural attitudes. Social Politics 19:163–193.

Bühlmann, Felix, Guy Elcheroth, and Manuel Tettamanti. 2009. The division of labour among European couples: the effects of life course and welfare policy on value–practice configurations. European Sociological Review 26:49–66.

Carlson, Daniel L., and Jamie L. Lynch. 2017. Purchases, penalties, and power: the relationship between earnings and housework. Journal of Marriage and Family 79:199–224.

Centre for Time Use Research. 2018. Multinational time use study. https://www.timeuse.org/mtus. Accessed 9 June 2018.

Charles, Maria, and David B. Grusky. 2004. Occupational ghettos: the worldwide segregation of women and men. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Cipollone, Angela, Eleonora Patacchini, and Giovanna Vallanti. 2014. Female labour market participation in Europe: novel evidence on trends and shaping factors. IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 3:18.

Coltrane, Scott. 2000. Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and Family 62:1208–1233.

Coltrane, Scott. 2010. Gender theory and household labor. Sex Roles 63:791–800.

Cooke, Lynn P. 2006. Policy, preferences, and patriarchy: the division of domestic labor in east Germany, west Germany, and the United States. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society 13:117–143.

Cooke, Lynn P. 2011. Gender-class equality in political economies. Abingdon: Routledge.

Cooke, Lynn P., and Janeen Baxter. 2010. “Families” in international context: Comparing institutional effects across western societies. Journal of Marriage and Family 72:516–536.

Cotter, David, Joan M. Hermsen, and Reeve Vanneman. 2011. The end of the gender revolution? Gender role attitudes from 1977 to 2008. American Journal of Sociology 117:259–289.

Cunningham, Mick. 2007. Influences of women’s employment on the gendered division of household labor over the life course: evidence from a 31-year panel study. Journal of Family Issues 28:422–444.

Cunningham, Mick. 2008. Influences of gender ideology and housework allocation on women’s employment over the life course. Social Science Research 37:254–267.

Davis, Shannon N., and Theodore N. Greenstein. 2004. Cross-national variations in the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family 66:1260–1271.

Davis, Shannon N., and Theodore N. Greenstein. 2009. Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology 35:87–105.

Dotti Sani, Giulia Maria. 2014. Men’s employment hours and time on domestic chores in European countries. Journal of Family Issues 35:1023–1047.

Elder, Glen H. 1998. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development 69:1–12.

Eliot, Lise. 2012. Pink brain, blue brain: how small differences grow into troublesome gaps—and what we can do about it. Richmond: Oneworld.

Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Ann Mische. 1998. What is agency? American Journal of Sociology 103:962–1023.

Erlinghagen, Marcel. 2019. Employment and its institutional context. In Cross-national comparative research – analytical strategies, results and explanations. Sonderheft Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, eds. Hans-Jürgen Andreß, Detlef Fetchenhauer and Heiner Meulemann. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00599-6.

Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Evertsson, Marie, and Daniela Grunow. 2016. Narratives on the transition to parenthood in eight European countries. The importance of gender culture and welfare regime. In Couples’ transitions to parenthood: analysing gender and work in Europe, ed. Daniela Grunow, Marie Evertsson, 269–294. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Evertsson, Marie, and Magnus Nermo. 2004. Dependence within families and the division of labor: comparing Sweden and the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family 66:1272–1286.

Fahlén, Susanne. 2016. Equality at home—A question of career? Housework, norms, and policies in a European comparative. Demographic Research 35:1411–1440.

Fuwa, Makiko. 2004. Macro-level gender inequality and the division of household labor in 22 countries. American Sociological Review 69:751–767.

Fuwa, Makiko, and Philip N. Cohen. 2007. Housework and social policy. Social Science Research 36:5112–5530.

Gangl, Markus, and Andrea Ziefle. 2015. The making of a good woman: extended parental leave entitlements and mothers’ work commitment in Germany. American Journal of Sociology 121:511–563.

Geist, Claudia. 2005. The welfare state and the home: regime differences in the domestic division of labour. European Sociological Review 21:23–41.

Geist, Claudia, and Philip N. Cohen. 2011. Headed toward equality? Housework change in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family 73:832–844.

Gershuny, Jonathan. 2018. Gender symmetry, gender convergence and historical work-time invariance in 24 countries. https://www.timeuse.org/sites/default/files/2018-02/CTUR%20WP%202%202018_0.pdf. Accessed 8 June 2018.

Gershuny, Jonathan, and Oriel Sullivan. 2003. Time use, gender, and public policy regimes. Social Politics 10:205–228.

Gershuny, Jonathan, Michael Bittman, and John Brice. 2005. Exit, voice, and suffering: do couples adapt to changing employment patterns? Journal of Marriage and Family 67:656–665.

Goerres, Achim, Markus B. Siewert and Claudius Wagemann. 2019. Internationally comparative research designs in the social sciences: Fundamental issues, case selection logics, and research limitations. In Cross-national comparative research – analytical strategies, results and explanations. Sonderheft Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, eds. Hans-Jürgen Andreß, Detlef Fetchenhauer and Heiner Meulemann. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00600-2.

Gornick, Janet C., and Marcia K. Meyers. 2003. Welfare regimes in relation to pad work and care. Advances in Life Course Research 8:45–67.

Greenstein, Theodore N. 2000. Economic dependence, gender, and the division of labor in the home: A replication and extension. Journal of Marriage and the Family 62:322–335.

Grunow, Daniela. 2017. Theoriegeleitetes Sampling für international vergleichende Mixed-Methods-Forschung. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 69:213–235.

Grunow, Daniela, and Gerlieke Veltkamp. 2016. Institutions as reference points for parents-to-be in European societies: A theoretical and analytical framework. In Couples’ transitions to parenthood: analysing gender and Work in Europe, ed. Daniela Grunow, Marie Evertsson, 3–33. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Grunow, Daniela, Katia Begall, and Sandra Buchler. 2018. Gender ideologies in Europe: A multidimensional framework. Journal of Marriage and Family 80:42–60.

Grunow, Daniela, Heather Hofmeister, and Sandra Buchholz. 2006. Late 20th-century persistence and decline of the female homemaker in Germany and the United States. International Sociology 21:101–131.

Grunow, Daniela, Florian Schulz, and Hans-Peter Blossfeld. 2012. What determines change in the division of housework over the course of marriage? International Sociology 27:289–307.

Gupta, Sanjiv. 2007. Autonomy, dependence, or display? The relationship between married women’s earnings and housework. Journal of Marriage and Family 69:399–417.

Gupta, Sanjiv, Marie Evertsson, Daniela Grunow, Magnus Nermo, and Liana C. Sayer. 2015. The economic gap among women in time spent on housework in former West Germany and Sweden. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 46:181–201.

Hakim, Catherine. 2000. Research design. Successful designs for social economics research. London: Routledge.

Hank, Karsten, and Hendrik Jürges. 2007. Gender and the division of household labor in older couples. Journal of Family Issues 28:399–421.

Hank, Karsten, and Anja Steinbach. 2019. Families and their institutional contexts: The role of family policies and legal regulations. In Cross-national comparative research – analytical strategies, results and explanations. Sonderheft Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, eds. Hans-Jürgen Andreß, Detlef Fetchenhauer and Heiner Meulemann. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00603-z.

Hays, Sharon. 1996. The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Heisig, Jan Paul. 2011. Who does more housework: rich or poor? A comparison of 33 countries. American Sociological Review 76:74–99.

Hitlin, Steven, and Glen H. Elder. 2007. Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory 25:170–191.

Hofmeister, Heather, Hans-Peter Blossfeld, and Melinda Mills. 2006. Globalization, uncertainty and women’s mid-career life courses: a theoretical framework. In Globalization, uncertainty and women’s careers: an international comparison, ed. Hans-Peter Blossfeld, Heather Hofmeister, 3–31. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hook, Jennifer L. 2006. Care in context: men’s unpaid work in 20 countries, 1965–2003. American Sociological Review 71:639–660.

Kan, Man Yee, Oriel Sullivan, and Jonathan Gershuny. 2011. Gender convergence in domestic work: Discerning the effects of interactional and institutional barriers from largescale data. Sociology 45:234–251.

Knight, Carly R., and Mary C. Brinton. 2017. One egalitarianism or several? Two decades of gender-role attitude change in Europe. American Journal of Sociology 122:1485–1532.

Knudsen, Knud, and Kari Wærness. 2008. National context and spouses’ housework in 34 countries. European Sociological Review 24:97–113.

Kohn, Melvin L. 1987. Cross-national research as an analytic strategy: American Sociological Association, 1987 Presidential Address. American Sociological Review 52:713–731.

Kühhirt, Michael. 2012. Childbirth and the long-term division of labour within couples: How do substitution, bargaining power, and norms affect parents’ time allocation in West Germany? European Sociological Review 28:565–582.

Lachance-Grzela, Mylène, and Geneviève Bouchard. 2010. Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research. Sex roles 63:767–780.

Lewin-Epstein, Noah, Haya Stier, and Michael Braun. 2006. The division of household labor in Germany and Israel. Journal of Marriage and Family 68:1147–1164.

Lewis, Jane E. 1993. Women and social policies in Europe: work, family and the state. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Mahmood, Saba. 2001. Feminist theory, embodiment, and the docile agent: some reflections on the Egyptian islamic revival. Cultural Anthropology 16:202–236.

Mandel, Hadas, and Moshe Semyonov. 2006. A welfare state paradox: State interventions and women’s employment opportunities in 22 countries. American Journal of Sociology 111:1910–1949.

Mencarini, Letizia, and Maria Sironi. 2010. Happiness, housework and gender inequality in Europe. European Sociological Review 28:203–219.

Mills, Melinda, Hans-Peter Blossfeld, and Fabrizio Bernardi. 2006. Globalization, uncertainty and men’s employment careers: a theoretical framework. In Globalization, uncertainty and men’s careers: An international comparison, ed. Hans-Peter Blossfeld, Melinda Mills, and Fabrizio Bernardi, 3–37. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Moen, Pyllis. 2003. Linked lives: dual careers, gender, and the contingent life course. In Social dynamics of the life course: transitions, institutions, and interrelations, 237–258.

Moreno-Colom, Sara. 2017. The gendered division of housework time: analysis of time use by type and daily frequency of household tasks. Time & Society 26:3–27.

Nazio, Tiziana. 2008. Cohabitation, family, and society. Routledge advances in sociology. New York: Routledge.

Neilson, Jeffrey, and Maria Stanfors. 2014. It’s about time! Gender, parenthood, and household divisions of labor under different welfare regimes. Journal of Family Issues 35:1066–1088.

Nitsche, Natalie, and Daniela Grunow. 2016. Housework over the course of relationships: gender ideology, resources, and the division of housework from a growth curve perspective. Advances in life course research https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2016.02.001.

Nordenmark, Mikael. 2004. Does gender ideology explain differences between countries regarding the involvement of women and of men in paid and unpaid work? International Journal of Social Welfare 13:233–243.

Orloff, Ann Shola. 1993. Gender and the social rights of citizenship: the comparative analysis of gender relations and welfare states. American Sociological Review 303–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095903

Orloff, Ann Shola. 2008. Should feminists aim for gender symmetry? Feminism and gender equality projects for a post-maternalist era. Paper presented at the annual conference of the International Sociological Association Research Committee on Poverty, Social Welfare and Social Policy, RC 19 The Future of Social Citizenship: Politics, Institutions and Outcomes. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.576.3826&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Date of access: 15 Aug. 2018)

Pfau-Effinger, Birgit. 2005. Culture and welfare state policies: reflections on a complex interrelation. Journal of social policy 34:3–20.

Pillarisetti, Jayasree, and Mark McGillivray. 2002. Human development and gender empowerment: methodological and measurement issues. Development Policy Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00059.

Pinchbeck, Ivy. 2013. Women workers in the industrial revolution. London: Routledge.

Presser, Harriet B. 1994. Employment schedules among dual-earner spouses and the division of household labor by gender. American Sociological Review 59:348–364.

Reimann, Maria. 2016. Searching for egalitarian divisions of care: polish couples at the life-course transition to parenthood. In Couples’ transitions to parenthood: analysing gender and work in Europe, ed. Daniela Grunow, Marie Evertsson, 221–242. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Robila, Mihaela. 2004. Families in eastern Europe: context, trends and variations. In Families in eastern Europe, 1–14. Oxford: Elsevier.

Ross, Catherine E. 1987. The division of labor at home. Social forces 65:816–833.

Ruppanner, Leah E. 2009. Conflict and housework: does country context matter? European Sociological Review 26:557–570.

Ruppanner, Leah E. 2010. Cross-national reports of housework: an investigation of the gender egalitarianism measure. Social Science Research 39:963–975.

Sainsbury, Diane. 1994. Gendering welfare states. Thousand Oakes: SAGE.

Sainsbury, Diane. 1996. Gender, equality and welfare states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sayer, Liana C. 2010. Trends in housework. In Dividing the domestic: men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective, ed. Judith Treas, Sonja Drobnič, 19–38. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Schmidt-Catran, Alexander W., Malcolm Fairbrother and Hans-Jürgen Andreß. 2019. Multilevel models for the analysis of comparative survey data: Common problems and some solutions. In Cross-national comparative research – analytical strategies, results and explanations. Sonderheft Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, eds. Hans-Jürgen Andreß, Detlef Fetchenhauer and Heiner Meulemann. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00607-9.

Schober, Pia S. 2013. Gender equality and outsourcing of domestic work, childbearing, and relationship stability among British couples. Journal of Family Issues 34:25–52.

Schröder, Martin. 2019. Varieties of capitalism and welfare regime theories: Assumptions, accomplishments, and the need for different Methods. In Cross-national comparative research – analytical strategies, results and explanations. Sonderheft Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, eds. Hans-Jürgen Andreß, Detlef Fetchenhauer and Heiner Meulemann. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00609-7.

Schulz, Florian, and Daniela Grunow. 2011. Comparing diary and survey estimates on time use. European Sociological Review 28:622–632.

Smith, Vicki. 2006. Work and employment. In The Cambridge dictionary of sociology, ed. Bryan S. Turner, 676–682. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sullivan, Oriel, and Jonathan Gershuny. 2016. Change in spousal human capital and housework: a longitudinal analysis. European Sociological Review 32:864–880.

Sullivan, Oriel, Francesco C. Billari and Evrim Altintas. 2014. Fathers’ changing contributions to child care and domestic work in very low–fertility countries: the effect of education. Journal of Family Issues 35:1048–1065.

Sullivan, Oriel, Jonathan Gershuny, and John P. Robinson. 2018. Stalled or uneven gender revolution? A long-term processual framework for understanding why change is slow. Journal of Family Theory & Review 10:263–279.

Tamilina, Larysa, and Natalya Tamilina. 2014. The impact of welfare states on the division of housework in the family: a new comprehensive theoretical and empirical framework of analysis. Journal of Family Issues 35:825–850.

Thébaud, Sarah. 2010. Masculinity, bargaining, and breadwinning: understanding men’s housework in the cultural context of paid work. Gender & Society 24:330–354.

Thébaud, Sarah, and David S. Pedulla. 2016. Masculinity and the stalled revolution: How gender ideologies and norms shape young men’s responses to work-family policies. Gender & Society 30:590–617.

Thévenon, Olivier. 2013. Drivers of female labour force participation in the OECD. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 145. Paris: OECD.

Thompson, Martha E., and Michael Armato. 2012. Investigating gender. Cambridge: Polity press.

Tilly, Louise A. 1994. Women, women’s history, and the industrial revolution. Social Research 61:115–137.

Tilly, Louise A., and Joan W. Scott. 1989. Women, work, and family. London: Psychology Press.

Treas, Judith. 2010. Why study housework? In Dividing the domestic: men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective, ed. Judith Treas, Sonia Drobnič, 3–18. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Treas, Judith, and Sonia Drobnič. 2010. Dividing the domestic: men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Treas, Judith, and Tsui Tai. 2016. Gender inequality in housework across 20 European nations: lessons from gender stratification theories. Sex Roles 74:495–511.

United Nations Development Programme. 2016. Gender Inequality Index (GII). http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-inequality-index-gii. Accessed 9 June 2018.

United Nations Development Programme. 2018. Human development report: gender inequality index. http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/GII. Accessed 9 June 2018.

Van der Lippe, Tanja, Judith de Ruijter, Esther de Ruijter, and Werner Raub. 2011. Persistent inequalities in time use between men and women: a detailed look at the influence of economic circumstances, policies, and culture. European Sociological Review 27:164–179.

Wall, Glenda. 2010. Mothers’ experiences with intensive parenting and brain development discourse. Women’s Studies International Forum 33:253–263.

West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. Doing gender. Gender & Society 1:125–151.

Yodanis, Carrie. 2005. Divorce culture and marital gender equality: a cross-national study. Gender & Society 19:644–659.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Yasemin Altintop, Bastian Ast and Luisa Bischoff for research assistance, Aline Gould for language editing and Miriam Bröckel, Marina Hagen and Catherine Hakim for comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Online Appendix: www.kzfss.uni-koeln.de/sites/kzfss/pdf/grunow.pdf

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grunow, D. Comparative Analyses of Housework and Its Relation to Paid Work: Institutional Contexts and Individual Agency. Köln Z Soziol 71 (Suppl 1), 247–284 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00601-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-019-00601-1