Abstract

Ability, motivation, and opportunity (AMO) approaches have dominated studies of knowledge sharing in multinational enterprises (MNEs). We argue that there is a need to consider both the national and organizational cultural contexts. Beyond their direct influence on knowledge sharing with colleagues in other business units (BUs), national and organizational culture significantly reinforce the positive relation between individual motivation and knowledge sharing. Thus, our multi-level approach to knowledge sharing in MNEs gives rise to a contextualized AMO approach that provides a novel and more potent understanding of variations in knowledge sharing. At the individual level, our approach includes the degree of ability in the sense of professional competence, intrinsic motivation, and opportunities to interact with colleagues in other BUs. At the organizational and country levels, we examine the direct and indirect effects of a collaborative culture on knowledge sharing. We employ data from an MNE that operates across a variety of regions, including the Nordic countries, Central and Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia. The sample consists of 11,484 individuals nested in 1235 departments in 11 countries. As well as confirming the significance of individual competence, intrinsic motivation, and opportunities for interaction for knowledge sharing, our findings reveal that both organizational culture and national culture are important factors for our understanding of knowledge sharing. This suggests that over and above recruiting intrinsically motivated employees, managers can enhance knowledge sharing by developing collaborative organizational cultures at the departmental level.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

For the multinational enterprise (MNE), the sharing of tacit forms of knowledge across borders is a source of innovation and competitive advantage (Goh, 2002; Grant, 1996; Kogut & Zander, 1992). Indeed, “the MNE’s unique role of gaining new knowledge and capabilities in foreign locations and transferring this knowledge across borders to be shared throughout the organization as a basis of value creation and competitive advantage for the MNE” is now viewed as “fundamental to the theory of the MNE” (Kim et al., 2020, p. 1057). While knowledge sharing occurs at various levels, at its base are the actions and behaviors of individual employees who share knowledge with colleagues (Foss & Pedersen, 2019). However, any comprehensive account of knowledge sharing in MNEs must be sensitive to the organizational and national cultural contexts in which employees are embedded (Foss & Pedersen, 2019; Grant & Phene, 2022).

A core approach to identifying the antecedents of individuals’ knowledge sharing has been to adopt the dominant approach to studying employee performance within HRM – the ability, motivation, and opportunity (AMO) framework (Appelbaum et al., 2000; Boxall, 2003; Paauwe, 2009). AMO distinguishes among individuals’ abilities (A) and motivation (M) as well as the opportunities (O) provided by the context in which individuals interact. In the MNE context, the AMO framework implies that if individuals have sufficient opportunities to build networks with colleagues in other business units (BUs), variations in their knowledge-sharing behavior are a product of their ability or professional competence and their motivation, including their intrinsic motivation (Gagné & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Connell, 1989).

Examples of studies that have framed the antecedents of knowledge sharing in terms of the three main drivers in the AMO framework include Argote et al. (2003), Jiang et al. (2012), Kim et al. (2015), and Reinholt et al. (2011). However, despite their significant contributions to pinpointing and modelling the antecedents of knowledge sharing, a significant shortcoming of extant applications of the AMO framework is their failure to consider the “social context” in which individuals share knowledge (Grant & Phene, 2022, p. 18). We address this issue by arguing that beyond their direct influence on knowledge sharing, collaborative national and organizational cultures significantly reinforce the positive relation between individual motivation and knowledge sharing with colleagues in other BUs.

Consider, for instance, the role of national culture. A particular feature of MNEs is that they operate across national cultures, which Hofstede (1991, p. 5) defines as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” and Inglehart (1997, p. 15) defines as “a system of attitudes, values, and knowledge that is widely shared within a society.” We argue that in collaborative national cultures, the prevailing embedded assumption that sharing is customary not only enhances a willingness to share knowledge but also positively moderates the impact of motivation on knowledge sharing. Furthermore, we argue that organizational culture, in the sense of the prevailing norms and values in the departments in which individuals are located, plays a similar role. We also propose that the motivation element of the AMO framework is particularly sensitive to both the national and organizational contexts.

We are not alone in pointing to a need to consider a contextualized approach to studying variations in knowledge-sharing behavior in MNEs (Grant & Phene, 2022). For example, based on an extensive review of research on knowledge sharing in MNEs, Gaur et al. (2019) argue that an understanding of knowledge flows in MNEs requires a multi-level design involving the individual, firm, and country levels. However, little extant research has adopted such a design (Quigley et al., 2007). In their review of 52 knowledge-sharing studies, Foss and Pedersen (2019, p. 1611) find that “the overwhelming part of the articles (46 of 52) is single-level (macro–macro or micro–micro) studies of knowledge sharing, and only very few establish a link between the individual and organizational levels.” In linking the individual to both the organizational and national levels, our contextualized AMO study responds to Foss and Pedersen’s (2019) call to integrate micro- and macro-level explanations of knowledge sharing and to explore their interactions.

Our study’s empirical context is individual-level knowledge sharing among employees in Telenor, a telecommunication (telco) MNE headquartered in Norway. Well before the launch of our study, the company could be characterized as a multi-domestic MNE with relatively autonomous BUs that overwhelmingly employed local nationals (Elter et al., 2014). However, in its 2014 strategy document (Telenor, 2014a), Telenor articulated an ambition to become a “customer centric leader” and recognized that this would involve improving knowledge sharing across its BUs, “making it easier and more efficient to share best practices … across the Group.” Given its aim of enhancing knowledge sharing across its BUs, Telenor serves as a suitable context for studying the determinants of knowledge sharing.

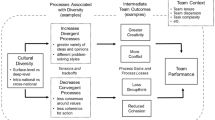

In the next section, we develop a contextualized AMO approach to knowledge sharing across MNEs’ BUs. We develop hypotheses for each of the three levels – individual, organizational, and national – as well as for cross-level interaction effects. Figure 1 summarizes our theoretical model.

In addition to confirming the roles of individual competence, motivation, and opportunity in forming cross-unit networks, we find that a collaborative organizational culture has a distinct, direct effect on knowledge sharing across BUs. Furthermore, we show that both the national and organizational cultural contexts in which MNE employees are embedded are of particular significance in moderating the impact of individual motivation on knowledge sharing. By applying a contextualized AMO framework, we not only address a research gap but also develop insights of significance for MNE managers. Our findings suggest that MNE managers aiming to enhance knowledge flows across BUs need to appreciate not only the effects of employee attributes on knowledge sharing but also the importance of developing collaborative organizational cultures at the departmental level.

2 Theoretical Framework

Enabling the geographical mobility of knowledge that is at least partially tacit, and is embodied in individuals’ skills and organizational practices is a key challenge for MNEs (Grant & Phene, 2022). Knowledge sharing with colleagues in other BUs requires deliberate behaviors on the part of the sender and the receiver (Felin & Hesterly, 2007; Foss & Pedersen, 2004; Foss et al., 2009; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; McDermott, 1999). Our contextualized approach to AMO points not just to individual-level factors but also to organizational and national-level factors that condition these behaviors (Gaur et al., 2019).

Given the need to avoid silo mentalities, various management fields have invested in identifying factors that are salient for enhancing knowledge sharing at the individual level (Cabrera et al., 2006; Gagné, 2009; Reinholt et al., 2011). As Edwards et al. (2013) argue, a consensus is emerging that the human resource (HR) factors that promote employee performance in general can be conceptualized according to the AMO framework (Appelbaum et al., 2000; Boselie et al., 2005; Paauwe, 2009). This framework can be traced back to Blumberg and Pringle’s (1982, p. 564) critique of theories of individual job performance, which accounted for individuals’ abilities and motivations but failed to acknowledge that “behavior also depends on the help or hindrance of uncontrollable events and actors in one’s environment. States of nature and actions of others are combined into a general category labeled opportunity.” In the work context, opportunities for knowledge sharing are often divided into formal, structural factors directly controllable by management and intangible, relational factors that emerge and form a platform for social interaction (Sterling & Boxall, 2013).

A number of studies that apply the AMO framework have provided insights into how individuals’ abilities and motivations affect knowledge sharing (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2006; Reinholt et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014). Some of these studies have also investigated how individuals’ perceptions of organizational opportunities affect knowledge-sharing behavior (Cabrera et al., 2006; Foss et al., 2009; Gagné, 2009). However, these studies ignore the organizational and national contexts of individual behavior and, thus, the simplicity of the model becomes a major limitation that might lead to biased estimates.

We address these shortcomings by applying a multilevel contextualized approach to the AMO framework. Not only do we examine the effects of individual-level AMO constructs on knowledge sharing, but we are also sensitive to the direct and cross-level moderating effects of the organizational and national collaborative cultural contexts.

2.1 Ability as an Individual Competence

Within the AMO framework, the concept of “ability” generally has no precise meaning beyond necessary skills (Bailey, 1993; Boselie et al., 2005), which may include formal and informal training and education (Appelbaum et al., 2000). In his framework of human resources in organizations, Nordhaug (1998) proposes the concept of work-related competences among individual employees that go beyond immediate task specificity and that span both firm and industry specificities. Cabrera et al. (2006) employ the concept of individual competence. They view high levels of individual competence as associated with a knowledge base that comprises tacit and explicit elements. In addition, they include cognitive processes comprising attention and memory that facilitate understanding and knowledge absorption in face-to-face peer interactions, which means that being a high-competency individual involves collegial acknowledgement.

Thus, rather than the somewhat tenuous notion of ability, we employ the concept of individual competence. This equates not only to formal education but also to job-related skills (Appelbaum, et al., 2000; Bello-Pintado, 2015; Jiang et al., 2012; Williams & Lee, 2016). In addition to general work experience, in-company management training is an important source of job-related skills. Furthermore, this concept of competence includes an element of collegial recognition of the expertise of those individuals as holders of superior and valuable competences.

Thus, we accept that competence is a source of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005) that enhances individuals’ sense of confidence in their own knowledge base, which in turn supports knowledge-sharing behaviors (Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005). At the same time, we emphasize that individuals with high levels of competence have valuable knowledge to share – a fact that must also be recognized by their colleagues (Szulanski, 1996; Yildiz et al., 2019). Thus, colleagues be receptive to highly competent individuals and they may even seek them out. Accordingly, we propose:

(H1a) Individual competence is positively associated with the frequency of knowledge sharing across BUs.

2.2 Individual Motivation

According to self-determination theory (SDT), individuals may differ in terms of their dominant motivation, with extrinsic motivation at one end of the scale and intrinsic motivation at the other (Gagné & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). Ryan and Deci (2000a, p. 56) define intrinsic motivation as “the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfactions rather than for some separable consequence.” Thus, it “involves people freely engaging in activities that they find interesting, that provide novelty and optimal challenge” (Deci & Ryan, 2000, p. 235). Intrinsic motivation is an important predictor of work performance in general (Ng et al., 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2017), and it is theoretically and empirically related to the promotion of knowledge sharing (Foss et al., 2009; Gagné, 2009; Lombardi et al., 2020).

Reinholt et al. (2011) show that intrinsically motivated individuals are more likely to proactively use their networks to search for required knowledge and to provide knowledge to others who might need it. Furthermore, intrinsically motivated knowledge sharing with colleagues in other BUs involves a sense that as well as being personally satisfying and enjoyable (Guay et al., 2000), knowledge sharing is of value and professional significance for others (Quigley & Tymon, 2006). In addition, intrinsic motivation is particularly important for the effort required to share the tacit components of knowledge (Gagné, 2009; Osterloh & Frey, 2000).

To paraphrase Bos-Nehles et al., (2013, p. 5), we view intrinsic motivation as an employee’s desire and willingness to share knowledge with colleagues in other BUs. Therefore, we hypothesize:

(H1b) Individual intrinsic motivation is positively associated with the frequency of knowledge sharing across BUs.

2.3 Individual Opportunities for Cross-BU Interaction

As Noorderhaven and Harzing (2009, p. 791) indicate, numerous researchers have argued that social interaction among managers from different BUs is important for stimulating intra-MNE knowledge-sharing (cf. Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1988; Gooderham, 2007; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; Williams & Lee, 2016): “face-to-face social interactions form a communication channel particularly conducive to the transfer of tacit, non-codified knowledge.” Tsai and Ghoshal (1998) employ the concept of structural social capital to refer to network or social interaction ties and observe that these ties enhance knowledge sharing across MNEs’ units. Nahapiet and Ghohsal (1998, p. 252) refer to these network ties as “the invisible college” and argue that “social relations, often established for other purposes, constitute information channels that reduce the amount of time and investment required to gather information.” Conversely, a lack of network ties across BUs impedes knowledge sharing. Thus, those individuals who have had opportunities to develop network ties through face-to-face interactions with colleagues in other BUs are more likely to share knowledge. This leads to the following hypothesis:

(H1c) Individual opportunities to interact with colleagues in other BUs are positively associated with the frequency of knowledge sharing across BUs.

2.4 The Organization Cultural Context

Organizational culture has been defined as “the basic assumptions and beliefs that are shared by organizational members” (Schein, 1985, p. 9). Building on this notion of culture within groups and organizations as “a social control system based on shared norms and values,” O’Reilly and Chatman (1996, p. 157) argue that it can influence members’ focus of attention and guide their behavior. Alavi et al. (2005) are skeptical of the suggestion of a unitary organizational culture. They argue that while there may be an underlying dominant organizational culture, various local cultures may exist, especially in large and complex organizations. Similarly, McDermott and O’Dell (2001, p. 77) observe that “organization culture is not homogeneous. There are always subcultures, sometimes simply different from the organization as a whole, sometimes in opposition to it.” Thus, organizational culture is a mix of local subcultures, each with their own distinctive values formed along the lines of functions, tasks, or technologies (De Long & Fahey, 2000). This means that in larger organizations, organizational culture as a concept may generally be more potent at the departmental level.

Quigley et al. (2007) show the significance of elements of the organizational culture that emphasize open exchange and reciprocation for knowledge sharing. A highly collaborative and reciprocating pattern of departmental behavior generates trust among members and affects how individuals assess the future behavior of their colleagues (Llopis & Foss, 2016; Quigley et al., 2007). Likewise, Alavi et al. (2005) find that collaborative and supportive values are particularly conducive to knowledge sharing. Thus, the higher the degree to which employees’ immediate social contexts, such as the departments in which they are located, are characterized by norms that encourage individuals to pursue joint outcomes (Collins & Smith, 2006; Quigley et al., 2007), the more likely knowledge sharing becomes (De Long & Fahey, 2000). In other words, employees embedded in collaborative department settings are more likely to assume that knowledge sharing is the norm across the MNE and to act upon that assumption. We hypothesize:

(H2a) The department’s collaborative culture is positively associated with the frequency of knowledge sharing across BUs.

We have argued that when highly cooperative and reciprocating departmental behavior is the norm, it affects levels of trust (Collins & Smith, 2006) and, therefore, the propensity to share knowledge across BUs. While individual competences and individual opportunity are factors that are essentially structural in character and, consequently, not particularly responsive to the organizational cultural context, we argue that intrinsic motivation is sensitive to the degree to which a department’s culture is collaborative.

We contend that intrinsic motivation is affected by the individual’s perception of departmental values and norms – that is, by what is considered acceptable and expected behavior within the departments (De Long & Fahey, 2000). Thus, in the context of collaborative departmental cultures that are characterized by dynamics of trust and supportive and reciprocal behaviors among departmental members (Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Wang et al., 2014), intrinsically motivated employees find validation for their inclination to engage in knowledge sharing. This positively reinforces the willingness of intrinsically motivated employees to share knowledge (Foss & Lindenberg, 2013; Gottschalg & Zollo, 2007; Minbaeva et al., 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). In short, when these two factors are aligned, they reinforce each other so that intrinsically motivated individuals who are located in departments with collaborative organizational cultures are particularly likely to engage in knowledge sharing. As such, in addition to the main effects of the organization’s collaborative culture on knowledge sharing, we propose that the departmental cultural context supports the positive effect of individual-level intrinsic motivation on knowledge sharing. This leads us to the following hypothesis:

(H2b) The department’s collaborative culture reinforces the positive relation between the intrinsic motivation of individuals and their frequency of knowledge sharing across BUs.

2.5 The National Cultural Context

We now turn to the role of national culture. Like Hofstede (1991), Rode et al. (2016) argue that a national culture consists of shared mental programs that exist within a nation’s population and that these programs shape individuals’ basic assumptions and cognition. In the context of individuals’ knowledge sharing with colleagues in other BUs, we focus on the specific aspects of culture that are conducive to this form of prosocial behavior.

Thomas et al. (2016) theorize that individuals in more individualistic cultures have a more transactional, less reciprocal approach to relationships. Similarly, Gelfand et al.’s (2004) observations suggest that low levels of individualism are particularly salient for prosocial behavior. They argue that research has shown that “patterns of social interaction vary in individualistic and collectivist cultures. Generally speaking, individuals are more likely to engage in activities alone in individualistic cultures” (Gelfand et al., 2004, p. 452). That is, in terms of the workings of organizations, in cultures with low levels of individualism “prosocial behaviors, or organization citizenship behaviors are (more) typical with organizational members assuming that they are highly interdependent with the organization and subject to organizational obligations” (Gelfand et al., 2004, p. 459). As such, prosocial behavior is associated with low levels of individualism or, in other words, high levels of collectivism.

Two influential approaches to conceptualizing and assessing levels of individualism and collectivism are found in Hofstede (1991) and GLOBE (House & Javidan, 2004). For Hofstede (2001, p. 225): “individualism stands for a society in which the ties between individuals are loose: Everyone is expected to look after her/his immediate family only.” In contrast to collectivistic societies, in individualistic societies “a child learns very early to think of itself as ‘I’ instead of as part of ‘we’. It expects one day to have to stand on its own feet and not get protection from its group anymore; and therefore, it also does not feel a need for strong loyalty” (Hofstede, 1994, p. 6). GLOBE (House & Javidan, 2004) underscores the assumption that societies that are characterized by low levels of individualism are associated with prosocial behaviors. As Rivera-Vazquez et al., (2009, p. 260) point out, “the collectivistic index, refers to awareness of employees that teamwork yields better results than individual work. They are more cooperative with others which promotes knowledge production and sharing with others in the organization.”

We argue that Hofstede’s (1994) approach is particularly useful regarding variations in individualism-collectivism and the associated prosocial behavior. While Hofstede (1994) focuses on measuring individualism in a society, low levels of individualism can be conceptualized as signifying a collaborative culture. Given our focus on knowledge sharing across BUs in MNEs, a further advantage to employing Hofstede’s (1994) measure of individualism is that he developed the scale in the work context using survey items that explicitly focused on work characteristics (Sturman et al., 2012). This makes it particularly suitable for our research.

Thus, we argue that the reverse of individualistic values is analogous to the prosocial behavior that constitutes a willingness to collaborate in sharing knowledge with colleagues in other BUs. We label this measure the “national collaborative culture” and hypothesize that employees located in highly collaborative cultures act on the assumption that knowledge sharing is the norm across the MNE. Thus:

(H3a) A national collaborative culture is positively associated with the frequency of knowledge sharing across BUs.

We have argued that knowledge sharing in collaborative national cultures derives support from the “individual’s loyalty toward the clan, organization or society – which is supposedly the best guarantee of that individual’s ultimate interest” (Hofstede, 1980a, p. 61). In an interview-based qualitative study of experts with a variety of professional backgrounds in Hong Kong and Germany, Wilkesmann et al.’s (2009) findings suggest that a collaborative national culture interacts positively with intrinsic motivation in relation to knowledge sharing. Similarly, in a meta-analysis of 44 studies involving 14,023 participants, Nguyen et al. (2019) reveal that the relationship between intrinsic motivation and knowledge sharing is strong in more collaborative national cultures. This leads us to argue that intrinsically motivated individuals located in collaborative, prosocial-behavior national cultures experience a sense of “moral” support for the personal satisfaction they derive from knowledge sharing. In contrast, intrinsically motivated individuals in non-collaborative national cultures “where the relationship between the individual and the organization is essentially calculative” (Hofstede, 1980a, p. 61) may experience some degree of misalignment with respect to their enjoyment of knowledge sharing for its own sake and the dominant cultural value that prescribes emotional independence and “enlightened self-interest” (Hofstede, 1980a, p. 61) for the organization. We hypothesize that:

(H3b) A collaborative national culture reinforces the positive relation between the intrinsic motivation of individuals and their frequency of knowledge sharing across BUs.

3 Methods

3.1 Sample and Data Collection

Our focus is on knowledge sharing in Telenor. For Telenor (Telenor, 2014b), the concept of knowledge spans “expertise” and “experience” related not only to technical issues but also to serving customers across different markets. We derived our data set from a survey of knowledge sharing among employees across Telenor’s 14 BUs conducted in 2014. In addition to four BUs in Norway (Telenor’s home country), Telenor had a BU in Denmark, Sweden, Hungary, Serbia, Montenegro, Malaysia, Thailand, India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan at the time of the survey.

Initially, we developed a pilot of the survey instrument and pretested it among 74 employees in Bangladesh and Telenor’s corporate headquarters in Norway. The aim was to obtain feedback from individuals located across a variety of task environments and two dissimilar national cultures in order to make certain that the survey instrument was comprehensible across the company. To ensure valid translation of the instrument, we employed several back-translation methods and pre-tests (Chidlow et al., 2014). In addition, we consulted 14 senior managers in Telenor’s R&D and HR departments both before and after the pilot study in order to finalize the instrument.

In March 2014, the knowledge-sharing survey was sent by internal e-mail to all 25,340 employees in Telenor’s BUs located across all its countries of operation. It was accompanied by an invitation letter from the CEO stressing the importance of the survey and including an assurance of anonymity. After three weeks, 15,793 employees had completed the questionnaire, which equates to a total response rate of 63 percent. The response rate exceeded 50 percent in all but three BUs and the response rate in all BUs was above 37 percent. Thereafter, to ensure a minimum level of responses from each department, we excluded all respondents located in departments with less than five responses. In order to exclude employees who had no opportunity to share knowledge with colleagues in other BUs, we remove respondents who indicated that they had not collaborated with colleagues in BUs other than their own. This reduced the number of respondents in our final sample to 11,484. These respondents were nested in 1235 departments, with an average of 9.3 respondents per department.

In addition, we linked our survey data on knowledge sharing with two additional sources of data: Telenor’s annual Employment Engagement Survey conducted in January 2014 and the company’s HR data on the respondents. Thus, we employed three different data sources. To the extent that the three data sets were collected at different points in time from the same individuals, we were able to validate parts of the knowledge-sharing survey data.

3.2 Measures

For most of the items in the hypothesized relationships, we used scales found in prior empirical studies. All new scales were based on adaptations of existing measures from the literature. For all multi-item constructs, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis in order to assess reliability and validity. More specifically, we calculated the values for composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach’s alpha (CA). Most of the data came from the knowledge-sharing survey, but some data were from the Employment Engagement Survey or the company’s HR records. In the following, we indicate when data was derived from sources other than the knowledge-sharing survey.

3.2.1 Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable is the extent of the individual’s knowledge sharing across BUs within the same MNE (Telenor), a measure that was inspired by Gupta and Govindarajan (2000), who likewise measured intra-organizational knowledge sharing. We used four items to measure the dependent variable. For each item, respondents were asked to use a seven-point scale ranging from “never” (= 1) to “very often” (= 7) to indicate how often they shared knowledge with colleagues in other BUs on “customer groups and markets,” “new service development,” “technology and telecom infrastructure,” and “new ways to serve customers.” The construct demonstrated strong reliability with a CR of 0.96, an AVE of 0.78, and a CA of 0.96.

3.2.2 Independent Variables

3.2.2.1 Individual Competence

The extant literature includes various proxies for individuals’ ability, such as role breadth self-efficacy (Andreeva & Sergeeva, 2016); tenure (Cabrera et al., 2006); and involvement in job rotation, training, and career development (Reinholt et al., 2011). Telenor’s approach to assessing the competence of individual employees was to assess the level of formal education, participation in company management training, and whether employees had been accorded the status of “company expert.” On this basis, our measure comprised four binary items (0–1) that we derived from Telenor’s HR data: individuals with at least a master’s degree, individuals who had participated in management training, individuals who had participated in specialized training in their area of expertise, and individuals who were recognized as experts in the company. As such, individual competence is a formative index ranging from 0 to 4 where 0 is low and 4 is high. As a robustness check, we ran all models for each component separately.

3.2.2.2 Intrinsic Motivation

We apply insights and scales from self-determination theory on motivation that clearly distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Foss et al., 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2000a). Respondents were asked to indicate the reasons that they shared knowledge with others using a seven-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (= 1) to “strongly agree” (= 7). We used four items: “I find it personally satisfying,” “I like sharing knowledge,” “I think it is an important part of my job,” and “I feel I have knowledge that can be useful for others” (CR = 0.85, AVE = 0.59, CA = 0.84).

3.2.2.3 Individual Opportunity

In order to assess the individual respondents’ opportunities to develop collegial relations across BUs, we asked them to indicate whether they had participated in job rotation across different BUs, participated in general training; and participated in seminars and workshops involving other BUs. We counted the number of interaction activities in which the individual had engaged with other BUs. Thus, the opportunity scale ranged from 0 to 3.

3.2.2.4 Departmental Collaborative Culture

Members of a department are exposed to common normative features in the organization. Our focus is on the degree to which members of a department perceive a collaborative culture. We measured collaborative culture using the organizational culture profile (OCP) developed by O’Reilly et al. (1991). As suggested by O’Reilly et al. (1991), we utilize a seven-point scale ranging from “most uncharacteristic” (= 1) to “most characteristic” (= 7) to measure the individual’s perception of a collaborative culture in relation to each of four items describing the values of their department: “Working in collaboration with others,” “Team oriented,” “Cooperative,” and “Supportive” (CR = 0.89, AVE = 0.68, CA = 0.89). The construct for departmental collaborative culture was the average of the four items.

In order to justify the aggregation of individual-level responses to the departmental level, the extent to which perceptions are shared within the department should be evaluated by analyzing the interrater agreement and interrater reliability or, more specifically, the similarity measures of Rwg and ICC(2) (LeBreton & Senter, 2008). For collaborative culture, we obtained satisfactory values of 0.70 for Rwg and 0.98 for ICC(2), which allowed us to average the individual-level responses in each unit to represent the department collaborative culture.

3.2.2.5 National Collaborative Culture

There were some non-indigenous employees in Telenor’s BUs and we could identify the country in which each individual was embedded. In order to operationalize our notion of national collaborative culture, we employed Hofstede’s (1980b) national-level measure of individualism (spanning from 0 to 100). As the converse of individualism corresponds to the collaborative values underlying the prosocial behavior of knowledge sharing with colleagues in other BUs, we reverse-coded Hofstede’s (1980b) measure of individualism.

3.2.3 Control Variables

We acknowledge that a range of other organizational features may affect the sharing of knowledge across BUs, including workloads (Marrone et al., 2007), customer-satisfaction focus, the extent to which individuals are empowered in their jobs, and the use of performance-related rewards (Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Foss et al., 2009). Thus, we controlled for individual perceptions of workload (“My workload is reasonable”) and the importance individuals attached to customer satisfaction with the company (“External customers should be extremely satisfied with the quality of our services”). We derived both from our second data source (i.e., Telenor’s Employment Engagement Survey). Our measure of empowerment comprised three items (CR = 0.83, AVE = 0.63, CA = 0.83) from the knowledge-sharing survey. From the company’s HR data, we derived a measure of whether part of the focal individual’s salary was based on performance (1 or 0). We labelled this measure rewards.

As the factors promoting knowledge sharing might work differently when sharing knowledge on, for example, technology as opposed to sales, we added control variables for function (i.e., dummy variables for sales, technology, R&D, supply chain, and administration). To control for variations in departmental size, we included a variable to capture departmental size. For both departmental function and departmental size, the data stemmed from the company’s HR data. Finally, as both gender and tenure might affect knowledge-sharing behavior (Cabrera et al., 2006), we drew from the knowledge-sharing survey to control for these factors.

Common method bias is an obvious limitation of survey-based measures (Chang et al., 2010). As we derived our data from three sources, this should be less of an issue in our study. Nevertheless, we undertook several statistical analyses to assess the severity of common method bias. A Harman’s one-factor test on the variables indicated that common method bias was not a major issue, as multiple factors were detected and the variance did not stem only from the first factors (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986).

Another potential concern with our data is endogeneity – that is, some of our variables might be determined by omitted variables. We approached this issue by conducting the Hausman specification test, whereby we were able to use instrumental variables from the Employment Engagement Survey (e.g., on motivation, satisfaction, and competence) rather than variables obtained from the knowledge survey. We employed the Hausman test in separate (3SLS) models for each of our hypothesized variables (the three AMO variables and the two context variables; i.e., five models in total). For example, for the Hausman test on the endogeneity between individual opportunity and knowledge sharing, we used the following three variables (from the Employment Engagement Survey): (1) “I am proud to work for my company,” (2) “Overall, I am extremely satisfied with my company as a place to work,” and (3) “I would recommend my company to others as a good place to work.” These variables fulfill the relevancy and exclusion restrictions for instrumental variables, as they explain a substantial part of the variation in individual opportunity but are only marginally related to knowledge sharing. Combined with the use of variables from three data sources in all models, the relatively low correlations (see Table 1), and the fact that our models span three levels, this test indicates that endogeneity is not a major concern.

Given the multilevel nature of the hypotheses and the nested structure of the data, the most appropriate model for testing our hypotheses is a random coefficients model in which we let the coefficient of the moderator vary across departments and nations (Preacher et al., 2016). We applied a hierarchical linear model based on the variance decomposition at the three levels. In addition, we standardized all variables with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 before running the models, as the models include interaction effects with variables on different scales.

4 Results

Table 1 depicts bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations before the variables are standardized. The table does not suggest that collinearity is an issue, as all correlations are below the standard threshold of 0.4.

The results of the multilevel analysis are listed in Table 2, which contains four models. In Model 1, we present the results of the null model without any explanatory variables. The variance components for the intercept at both the departmental (β = 0.218, p < 0.001) and national levels (β = 0.277, p < 0.006) are significant in this model, indicating a substantial range in mean knowledge sharing across departments and countries. No less than 14 percent of the total variance in individuals’ knowledge sharing resides at the departmental level (6 percent) and the national level (8 percent).

Model 2 introduces the control variables. Except for tenure, they are all statistically significant. The addition of these control variables reduces the unexplained variation at the individual level by 4 percent, while the unexplained variation at the departmental level decreases by 17 percent, indicating that the control variables explain 17 percent of the variation at the departmental level. The national level contributes an additional 3 percent. This relatively powerful explanatory role of the organizational level is a feature of Models 3 and 4.

In Model 3, we add all of the main effects of our five hypothesized variables (i.e., individual competence, intrinsic motivation, opportunity, collaborative organizational culture, and collaborative national culture) on the three levels. While collaborative national culture is insignificant (p = 0.120), the other four variables are highly significant (p < 0.001). Notably, when adding these five variables, the variation on all three levels decreases substantially, suggesting that the explanatory power increases to 11, 42, and 41 percent on the individual, departmental, and national levels, respectively.

Model 4, which is the fully specified model, incorporates the two hypothesized interaction effects. In relation to Model 3, the explanatory power is largely unchanged at 12, 43, and 42 percent on the individual, departmental, and national levels, respectively. The results show that the interaction between collaborative organizational culture and intrinsic motivation is positive and highly significant (β = 0.06, p < 0.001). To graph the interaction, we plotted the simple slopes for the relationship between individuals’ intrinsic motivation and knowledge sharing at one standard deviation above and below the mean of collaborative organizational culture (Fig. 2). The figure shows that knowledge-sharing behavior increases when both the collaborative organizational culture and intrinsic motivation are high. The dotted line shows that employees with high levels of intrinsic motivation are more influenced by collaborative organizational culture. In contrast, the effect of a collaborative organizational culture is weaker for employees with low levels of intrinsic motivation. The slopes of the two lines differ, indicating that a high collaborative culture strongly reinforces the effect of intrinsic motivation on knowledge sharing. The interaction between collaborative national culture and intrinsic motivation is also positive but only marginally significant (β = 0.03, p < 0.030). Similarly, in Fig. 3, we graph the interaction for the relationship between individuals’ intrinsic motivation and knowledge sharing at one standard deviation above and below the mean of collaborative national culture. The figure shows that knowledge-sharing behavior increases with intrinsic motivation when the collaborative national culture is either low or high. In fact, the slopes of the two lines are similar, indicating that the level of national collaborative culture only reinforces the effect of intrinsic motivation on knowledge sharing to a small extent. The significant main effects in Model 3 are also evident in Model 4, which includes the added interaction effects.

Overall, the results indicate that the three individual-level variables (i.e., individual competence, motivation, and opportunity) have strong, positive effects on knowledge sharing across business units. Thus, we find support for H1a, H1b, and H1c. While a collaborative organizational culture has a significant direct effect on knowledge sharing, this is not the case for a collaborative national culture. Thus, H2a is supported but H3a is not. When we test for the interaction of these two variables with intrinsic motivation, we find support for both H2b and H3b but the interaction involving collaborative organizational culture has a more pronounced effect.

As robustness checks, we ran a number of alternative models, such as split-sample models for Nordic, European, and Asian countries, and we removed individual countries from the sample to determine whether single countries were driving the results (e.g., Norway as the home country). Similarly, we ran the models separately for each function. In all of these alternative models, the results were qualitatively similar (although typically weaker).

5 Discussion and Conclusion

As individuals engage in knowledge sharing, theorizing about individual attributes is an important task. Nevertheless, as Foss and Pedersen (2019, p. 1597) argue in their overview of knowledge sharing in MNEs, while individuals’ characteristics and behaviors are important:

The evidence is overwhelming that context matters, as any IM (international management) scholar knows, but it matters because it influences individual characteristics and behaviors. Thus, context influences what is the available action set (i.e., opportunity), as well as the cognition (attention) and motivation (affect) of individuals within the context. Leaving context out would therefore amount to under-specification and to sacrificing valuable information.

However, for pragmatic reasons, few studies of knowledge sharing in MNEs have utilized a multi-level design that examines multi-level interaction effects (Gooderham et al., 2011). Using a multi-level approach, we find that all three individual variables contribute to variations in knowledge sharing across business units – a finding that is in line with previous AMO research. However, our inclusion of context reveals that both organizational and national collaborative cultures must be taken into consideration. Not only does the organization’s collaborative culture have a direct effect on knowledge sharing, but both organizational and national culture also positively and significantly moderate individuals’ intrinsic motivation.

As such, our most substantial contribution to knowledge sharing in MNEs is the introduction and validation of the notion of contextualized AMO. In short, AMO explanations of knowledge sharing in MNEs must be sensitive to multi-level contextual interaction effects. In addition, our study contributes to the motivation literature (Gagné & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). Furthermore, as we find a collaborative organizational culture to be a potent explanatory factor for knowledge sharing, our study contributes to the organizational culture literature (O’Reilly & Chatman, 1996; O’Reilly et al., 1991).

5.1 Managerial Implications

Our contextualized approach to AMO has both established and novel implications for managers of MNEs who wish to promote knowledge sharing across BUs. While managers should be aware of the importance of recruiting and developing individuals in terms of their competences and intrinsic motivations for knowledge sharing (Gagné, 2009), they should also create opportunities for collegial interaction across BUs. Furthermore, managers should keep in mind the importance of stimulating individuals’ intrinsic motivations (Gagné & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). What might this mean in practice? Based on SDT, Gagné (2009, p. 583) makes several suggestions for managerial practice in response to the question of “how to develop and design HRM practices that will promote intrinsic motivation to enhance knowledge sharing.” Gagné (2009) recommends that managers ensure that individuals experience autonomy in their work settings and encounter social support and relatedness among colleagues. At the same time, they should enhance individuals’ feelings of competence in their work settings. Gagné (2009, p. 583) also proposes that as “satisfying those three psychological needs is the key to promoting intrinsic motivation, one can design or redesign HRM practices to fulfill those needs.” It is also possible to train managers in transformational leadership to promote intrinsic motivation and foster knowledge-sharing norms (Dvir et al., 2002). Our findings regarding the interaction of collaborative national cultures with intrinsic motivation suggest that this type of intervention is particularly important in individualistic settings.

As well as demonstrating the importance of managers taking individual factors into account, our study points to the need to consider the quality of collaborative organizational culture within departments. Indeed, as our paper has shown, a considerable part of the variation in knowledge sharing can be explained by cultural factors at the departmental level. These factors create “the context for social interaction” that “determines” the degree of knowledge sharing across business units (De Long & Fahey, 2000, p. 126). Unlike national culture, organizational culture is a relatively malleable factor – that is, as Cabrera and Cabrera (2005) argue, managers have the discretion to affect knowledge sharing across departments by developing collaborative departmental cultures.

Arguably, managers will find it more challenging to view a collaborative organizational culture and intrinsic motivation not just as discrete factors that promote knowledge sharing but as factors that interact. One possible way to facilitate this understanding is to encourage managers to carefully examine the characteristics of their “best-” and “worst-case” knowledge-sharing departments in terms of both factors.

5.2 Limitations and Future Research

Inevitably, one limitation of a study involving concepts like individual competence, intrinsic motivation, opportunity, and organizational and national cultures relates to their operationalization. This may be particularly true for national collaborative culture. Following researchers like Brewer and Venaik (2011), who view Hofstede’s individualism-collectivism measure as better at capturing levels of individualism than collectivism, we reversed Hofstede’s individualism scale to form a measure of what we label national collaborative culture. Future research may benefit from a more direct and intended measure of this concept.

A second limitation is the cross-sectional and, therefore, non-longitudinal nature of our data, which means that we cannot dismiss some degree of reverse causality. For example, it is possible that individuals who share knowledge come to be recognized by colleagues as having expertise and are provided with opportunities to further develop their competence. Likewise, the act of sharing knowledge may increase individuals’ intrinsic motivation. Our approach to limiting common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012) was to collect data from three sources. We also controlled for alternative explanations using various controls. Nevertheless, we recommend that future research should seek opportunities to collect data at different points in time.

A third limitation concerns our conceptualization of individuals’ knowledge sharing with colleagues in other BUs. Our conceptualization does not consider the possibility of particularly strong or weak bilateral flows of knowledge across Telenor at the BU level. Moreover, it does not enable us to gauge whether individuals located in certain BUs played more active roles than individuals in other BUs.

A final limitation relates to our research setting. As we have noted, Telenor does not attempt to promote knowledge sharing using extrinsic rewards. Previous research suggests that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation may have direct, positive effects on knowledge sharing (see, e.g., Argote et al., 2003; Gagné, 2009; Osterloh & Frey, 2000). Future research should therefore consider selecting research settings that combine both forms of motivation.

References

Alavi, M., Kayworth, T. R., & Leidner, D. E. (2005). An empirical examination of the influence of organizational culture on knowledge management practices. Journal of Management Information Systems, 22(3), 191–224.

Andreeva, T., & Sergeeva, A. (2016). The more the better… or is it? The contradictory effects of HR practices on knowledge-sharing motivation and behavior. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(2), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12100

Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2000). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. ILR Press.

Argote, L., McEvily, B., & Reagans, R. (2003). Managing knowledge in organizations: An integrative framework and review of emerging themes. Management Science, 49(4), 571–582.

Bailey, T. R. (1993). Discretionary effort and the organization of work: Employee participation and work reform since Hawthorne. Teachers College and Conservation of Human Resources, Columbia University.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Bello-Pintado, A. (2015). Bundles of HRM practices and performance: Empirical evidence from a Latin American context. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(3), 311–330.

Blumberg, M., & Pringle, C. D. (1982). The missing opportunity in organizational research: Some implications for a theory of work performance. Academy of Management Review, 7, 560–569. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1982.4285240

Boselie, P., Dietz, G., & Boon, C. (2005). Commonalities and contradictions in HRM and performance research. Human Resource Management Journal, 15(3), 67–94.

Bos-Nehles, A. C., Van Riemsdijk, M. J., & Kees Looise, J. (2013). Employee perceptions of line management performance: Applying the AMO theory to explain the effectiveness of line managers’ HRM implementation. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 861–877.

Boxall, P. (2003). HR strategy and competitive advantage in the service sector. Human Resource Management Journal, 13(3), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2003.tb00095.x

Brewer, P., & Venaik, S. (2011). Individualism–collectivism in Hofstede and GLOBE. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(3), 436–445.

Cabrera, A., Collins, W. C., & Salgado, J. F. (2006). Determinants of individual engagement in knowledge sharing. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(2), 245–264.

Cabrera, E. F., & Cabrera, A. (2005). Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(5), 720–735.

Chang, S. J., Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 178–184.

Chidlow, A., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Welch, C. (2014). Translation in cross-language international business research: Beyond equivalence. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(5), 562–582.

Collins, C. J., & Smith, K. G. (2006). Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 544–560.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

De Long, D. W., & Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. Academy of Management Perspectives, 14(4), 113–127.

Dvir, T., Eden, D., Avolio, B. J., & Shamir, B. (2002). Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 45(4), 735–744.

Edwards, P. K., Sánchez-Mangas, R., Tregaskis, O., Lévesque, C., McDonnell, A., & Quintanilla, J. (2013). Human resource management practices in the multinational company: A test of system, societal, and dominance effects. ILR Review, 66(3), 588–617.

Elter, F., Gooderham, P. N., & Ulset, S. (2014). Functional-level transformation in multi-domestic MNCs: Transforming local purchasing into globally integrated purchasing. In T. Pedersen, M. Venzin, T. M. Devinney, & L. Tihanyi (Eds.), Orchestration of the global network organization. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Felin, T., & Hesterly, W. S. (2007). The knowledge-based view, nested heterogeneity, and new value creation: Philosophical considerations on the locus of knowledge. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 195–218.

Foss, N. J., & Lindenberg, S. (2013). Microfoundations for strategy: A goal-framing perspective on the drivers of value creation. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(2), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0103

Foss, N. J., Minbaeva, D. B., Pedersen, T., & Reinholt, M. (2009). Encouraging knowledge sharing among employees: How job design matters. Human Resource Management, 48(6), 871–893.

Foss, N. J., & Pedersen, T. (2004). Organizing knowledge processes in the multinational corporation: An introduction. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 340–346.

Foss, N. J., & Pedersen, T. (2019). Microfoundations in international management research: The case of knowledge sharing in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1594–1621.

Gagné, M. (2009). A model of knowledge-sharing motivation. Human Resource Management, 48(4), 571–589.

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362.

Gaur, A. S., Ma, H., & Ge, B. (2019). MNC strategy, knowledge transfer context, and knowledge flow in MNEs. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(9), 1885–1900.

Gelfand, M. J., Lim, B. C., & Raver, J. L. (2004). Culture and accountability in organizations: Variations in forms of social control across cultures. Human Resource Management Review, 14(1), 135–160.

Ghoshal, S., & Bartlett, C. A. (1988). Creation, adoption, and diffusion of innovations by subsidiaries of multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(3), 365–388.

Goh, S. C. (2002). Managing effective knowledge transfer: An integrative framework and some practice implications. Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(1), 23–30.

Gooderham, P., Minbaeva, D. B., & Pedersen, T. (2011). Governance mechanisms for the promotion of social capital for knowledge transfer in multinational corporations. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1), 123–150.

Gooderham, P. N. (2007). Enhancing knowledge transfer in multinational corporations: A dynamic capabilities driven model. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 5(1), 34–43.

Gottschalg, O., & Zollo, M. (2007). Interest alignment and competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 418–437. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351356

Grant, R., & Phene, A. (2022). The knowledge based view and global strategy: Past impact and future potential. Global Strategy Journal, 12(1), 3–30.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122.

Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2000). On the assessment of situational intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motivation and Emotion, 24(3), 175–213.

Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge flows within multinational corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 473–496.

Hofstede, G. (1980a). Motivation, leadership and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9, 42–63.

Hofstede, G. (1980b). Values and culture. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (1994). Management scientists are human. Management Science, 40(1), 4–13.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage.

House, R. J., & Javidan, M. (2004). Overview of GLOBE. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 9–26). Sage.

Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution: Changing values and political values. Princeton University Press.

Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012). How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1264–1294.

Kim, K. Y., Pathak, S., & Werner, S. (2015). When do international human capital enhancing practices benefit the bottom line? An ability, motivation and opportunity perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2015.10

Kim, M., Lampert, C. M., & Roy, R. (2020). Regionalization of R&D activities:(Dis) economies of interdependence and inventive performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(7), 1054–1075.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397.

LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852.

Llopis, O., & Foss, N. J. (2016). Understanding the climate–knowledge sharing relation: The moderating roles of intrinsic motivation and job autonomy. European Management Journal, 34(2), 135–144.

Lombardi, S., Cavaliere, V., Giustiniano, L., & Cipollini, F. (2020). What money cannot buy: The detrimental effect of rewards on knowledge sharing. European Management Review, 17(1), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12346

Marrone, J. A., Tesluk, P. E., & Carson, J. B. (2007). A multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of team member boundary-spanning behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 50(6), 1423–1439. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.28225967

McDermott, R. (1999). Why information technology inspired but cannot deliver knowledge management. California Management Review, 41(4), 103–117.

McDermott, R., & O’Dell, C. (2001). Overcoming cultural barriers to sharing knowledge. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(3), 76–85.

Minbaeva, D. B., Mäkelä, K., & Rabbiosi, L. (2012). Linking HRM and knowledge transfer via individual-level mechanisms. Human Resource Management, 51(3), 387–405.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

Ng, J. Y., Ntoumanis, N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Duda, J. L., & Williams, G. C. (2012). Self-determination theory applied to health contexts a meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612447309

Nguyen, T.-M., Nham, T. P., Froese, F. J., & Malik, A. (2019). Motivation and knowledge sharing: A meta-analysis of main and moderating effects. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(5), 998–1016. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2019-0029

Noorderhaven, N., & Harzing, A. W. (2009). Knowledge-sharing and social interaction within MNEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(5), 719–741.

Nordhaug, O. (1998). Competence specificities in organizations: A classificatory framework. International Studies of Management and Organization, 28(1), 8–29.

O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. A. (1996). Culture as social control: Corporations, cults, and commitment. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 157–200.

O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Osterloh, M., & Frey, B. S. (2000). Motivation, knowledge transfer, and organizational forms. Organization Science, 11(5), 538–550.

Paauwe, J. (2009). HRM and performance: Achievements, methodological issues and prospects. Journal of Management Studies, 46(1), 129–142.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544.

Preacher, K. J., Zhang, Z., & Zyphur, M. J. (2016). Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000052

Quigley, N. R., Tesluk, P. E., Locke, E. A., & Bartol, K. M. (2007). A multilevel investigation of the motivational mechanisms underlying knowledge sharing and performance. Organization Science, 18(1), 71–88.

Quigley, N. R., & Tymon, W. G. (2006). Toward an integrated model of intrinsic motivation and career self-management. Career Development International, 11(6), 522–543.

Reinholt, M., Pedersen, T., & Foss, N. J. (2011). Why a central network position isn’t enough: The role of motivation and ability for knowledge sharing in employee networks. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1277–1297.

Rivera-Vazquez, J. C., Ortiz-Fournier, L. V., & Rogelio Flores, F. (2009). Overcoming cultural barriers for innovation and knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(5), 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270910988097

Rode, J. C., Huang, X., & Flynn, B. (2016). A cross-cultural examination of the relationships among human resource management practices and organisational commitment: An institutional collectivism perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(4), 471–489.

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 749–761.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000a). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Schein, E. A. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Sterling, A., & Boxall, P. (2013). Lean production, employee learning and workplace outcomes: A case analysis through the ability-motivation-opportunity framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 23(3), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12010

Sturman, M. C., Shao, L., & Katz, J. H. (2012). The effect of culture on the curvilinear relationship between performance and turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 46–62.

Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 27–43.

Telenor (2014a). Strategy for the Telenor Group 2014a–2016. Internal company document available on request from Telenor Research, Fornebu.

Telenor (2014b). Telenor organization culture survey. Internal company document available on request from Telenor Research, Fornebu.

Thomas, D. C., Ravlin, E. C., Liao, Y., Morrell, D. L., & Au, K. (2016). Collectivistic values, exchange ideology and psychological contract preference. Management International Review, 56, 255–281.

Tsai, W., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(4), 464–476.

Wang, S., Noe, R. A., & Wang, Z. M. (2014). Motivating knowledge sharing in knowledge management systems: A quasi-field experiment. Journal of Management, 40(4), 978–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311412192

Wilkesmann, U., Fischer, H., & Wilkesmann, M. (2009). Cultural characteristics of knowledge transfer. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(6), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270910997123

Williams, C., & Lee, S. H. (2016). Knowledge flows in the emerging market MNC: The role of subsidiary HRM practices in Korean MNCs. International Business Review, 25(1), 233–243.

Yildiz, H. E., Murtic, A., Zander, U., & Richtner, A. (2019). What fosters individual-level absorptive capacity in MNCs? An extended motivation-ability-opportunity framework. Management International Review, 59, 93–129.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the RaCE program “Radical Technology-driven Change in Established Firms”. Grant: The Research Council of Norway 294458.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian School Of Economics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gooderham, P.N., Pedersen, T., Sandvik, A.M. et al. Contextualizing AMO Explanations of Knowledge Sharing in MNEs: The Role of Organizational and National Culture. Manag Int Rev 62, 859–884 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-022-00483-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-022-00483-0