Abstract

This study examined alcohol misuse and binge drinking prevalence among Harlem residents, in New York City, and their associations with psycho-social factors such as substance use, depression symptom severity, and perception of community policing during COVID-19. An online cross-sectional study was conducted among 398 adult residents between April and September 2021. Participants with a score of at least 3 for females or at least 4 for males out of 12 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test were considered to have alcohol misuse. Binge drinking was defined as self-reporting having six or more drinks on one occasion. Modified Poisson regression models were used to examine associations. Results showed that 42.7% used alcohol before COVID-19, 69.1% used it during COVID-19, with 39% initiating or increasing alcohol use during COVID-19. Alcohol misuse and binge drinking prevalence during COVID-19 were 52.3% and 57.0%, respectively. Higher severity of depression symptomatology, history of drug use and smoking cigarettes, and experiencing housing insecurity were positively associated with both alcohol misuse and binge drinking. Lower satisfaction with community policing was only associated with alcohol misuse, while no significant associations were found between employment insecurity and food insecurity with alcohol misuse or binge drinking. The findings suggest that Harlem residents may have resorted to alcohol use as a coping mechanism to deal with the impacts of depression and social stressors during COVID-19. To mitigate alcohol misuse, improving access to mental health and substance use disorder services, and addressing public safety through improving relations with police could be beneficial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol misuse—including alcohol dependence and excessive drinking (e.g., binge drinking) [1]—is an important public health problem. Globally, alcohol misuse is the most prevalent substance abuse and is the seventh leading cause of death and disability-adjusted life years [2]. Additionally, alcohol misuse negatively impacts other long-term health issues due to positive associations with injuries, progression of liver fibrosis, duration of hospital days, mental health symptoms, prevalence of psychiatric episodes, physical and mental quality of life, and lower social functioning [3]. Furthermore, minoritized people suffer a greater impact from alcohol misuse than their white counterparts, with an increased association with job loss, housing insecurity, and a significantly higher risk of alcohol dependence and related consequences [4]. This problem worsened during COVID-19 when alcohol-related deaths increased by 25.5% between 2019 and 2020, indicating the pandemic’s impacts on behavioral health-related outcomes [5]. Furthermore, alcohol use disorder treatment remains underutilized in the USA, where approximately 7.2% of people aged 12 or older with alcohol use disorders received treatment in the past year in 2019 [6]. This is more pronounced with minoritized people, where studies have shown that minoritized people are less likely to complete treatment for alcohol use disorders [7].

In the USA, alcohol misuse increased by up to 20.0% during COVID-19, with non-Hispanic Black individuals drinking being more likely to excess recommended drinking limits than non-Hispanic white individuals [8]. Paralleling with an increase in alcohol consumption, the COVID-19 pandemic created economic hardship and increased the prevalence of mental health problems [9]. Recent studies showed that many people used substances (e.g., cannabis, alcohol) to cope with pandemic-related uncertainties, changes, and disruptions to daily life [10, 11], and there is a negative spiral between pandemic-related psychological distress and excessive alcohol use [12]. Alcohol consumption during COVID-19 in minoritized communities is a particular concern, as non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations are at higher risk of alcohol-related complications and long-term dependency during times of economic hardship [4], especially in hard-hit cities by the pandemic like New York City (NYC). More importantly, these vulnerable populations were disproportionately targeted for both outdoor advertising of alcohol [13] and alcohol retailers [14], which facilitates increased accessibility to alcohol for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic people. Therefore, evaluating the prevalence of alcohol misuse and its impacts will guide public policy on addressing alcohol misuse following the pandemic, especially among minoritized communities.

NYC was the American epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic with devastatingly profound impacts on minoritized communities. For example, Harlem—with nearly 80.0% of both East Harlem and Central Harlem residents identifying as Black and/or Hispanic [15, 16]—was most affected by the pandemic (e.g., rates of infection and death) and related socioeconomic and health disparities, including food insecurity, financial distress, and unmet mental health needs [17, 18]. Moreover, Harlem is one of NYC’s poorest neighborhoods with nearly 30.0% of all households in Central Harlem living below the federal poverty level and historically being medically underserved, with 20.0% of all residents lacking health insurance, and one in nine Harlem residents going without needed medical care [19]. Understanding the impacts of psycho-social factors (e.g., housing insecurity, food insecurity, employment insecurity) on patterns of alcohol consumption among the most hard-hit population in Harlem plays a critical role in prioritizing resources for alcohol misuse interventions following the pandemic. According to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2020, 14.2% of New Yorkers reported binge drinking [20], however, more updated data is needed, especially after the pandemic, to provide a more comprehensive depiction of alcohol misuse. Moreover, no studies have examined the impact of public perception of police on alcohol misuse and binge drinking. It is possible that a lower public satisfaction perception of police in the community may be associated with increased alcohol misuse and binge drinking. This study, therefore, fills the gap by comparing prevalence of alcohol use among Harlem residents before and after the start of the pandemic in the city in March 2020, and explores psycho-social factors such as substance use, depression symptom severity, and residents’ perception of community policing with alcohol misuse and binge drinking in a community with a predominantly Black population in NYC.

Methodology

Study Design and Sample Size

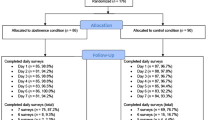

In this cross-sectional study, data were collected online via Qualtrics from April to September 2021. Eligible participants included those who were at least 18 years old and self-reported living in Harlem, NYC. To control for bots or spam responses, open-ended questions (e.g., “What is COVID-19?”) were added to the survey along with honeypot questions using JavaScript. Moreover, all participants were verified by (1) sending out emails to confirm collected information, (2) using Whitepages.com to check their phone number and address with self-reported data, and (3) through phone calls. This verification process ended up with a final of 437 eligible participants. However, 39 participants who did not disclose their gender were excluded because the standardized definition of alcohol misuse is gender-dependent [21]. A total of 398 participants were included in the final analyses.

Measurements

Alcohol Misuse

The primary outcome of interest was alcohol misuse, which was measured by using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) with 3 items. Each item was scored on a 0 to 4-point Likert scale, for example, “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol.” The Cronbach’s alpha for AUDIT-C in our study sample indicated acceptable internal consistency (0.79). A score of at least 3 for females and at least 4 for males out of 12 indicated alcohol misuse [22, 23]. Binge drinking during the pandemic included those who self-reported having six or more drinks on one occasion [22]. Binge drinking was classified as infrequent (if participants reported less than monthly or monthly) or frequent (if participants reported weekly, daily, or almost daily). Alcohol consumption prior to March 2020 was considered as drinking before pandemic and after March 2020 indicated drinking during pandemic.

Depression Severity

To assess depression symptomatology over the past 2 weeks, we administered the Patient Health Questionnaire with 4 items (PHQ-4) [24]. Responses were on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Nearly every day) for a summary score ranging from 0 to 12. Scores were rated as none (0–2), mild (3–5), moderate (6–8), and severe (9–12). The Cronbach’s alpha for PHQ-4 was 0.80, indicating good internal consistency.

Social Risk Factors

This includes four binary domains (yes/no) based on questions as follows: (1) employment insecurity was defined in individuals who (a) did not work since the beginning of the pandemic, (b) worked part-time on and off throughout those months, and (c) did not receive payment for the time they were not working; (2) housing insecurity included those who fell into one of the following categories: (a) currently live in a shelter; (b) have been evicted; and/or (c) somewhat/very difficult to pay for rent or mortgage; (3) food insecurity: Participants belonged to this group if they (a) did often/sometimes not enough to eat; and/or (b) could not afford to buy more food; and (4) childcare challenges: If participants responded either having somewhat/very difficult time with childcare or the main reason for not working was to care for their children who were not in school or daycare.

Interpersonal Violence

The Humiliation, Afraid, Rape, Kick (HARK) questions were used to evaluate interpersonal violence [25]. The scale included four binary questions assessing the exposure to violence in the home since the start of the pandemic (e.g., “Been humiliated or emotionally abused in any way by anyone in your household?” or “Been afraid that anyone in your household would do something to hurt you?”). A participant would test positive for experiencing interpersonal violence if they answered “yes” to any of the four items. The Cronbach’s alpha for HARK was 0.70 indicating good internal consistency.

Perceptions of Police

We developed a 10-item questionnaire such as, “The police are responsive to calls from my community” or “I find the police to be helpful in managing crime in my neighborhood.” Each item was scored from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), and total score ranged from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction with police in the community.

Demographics

We assessed age in years, gender (male and female), race/ethnicity (white vs. not white), born outside the USA (yes vs. no), currently married (yes vs. no), household size (only yourself, yourself and another, and 3–8 people), educational attainment (high school and less, associate’s or college’s degree, bachelor or graduate degree), employment status (unemployed vs. employed), work changed during the COVID-19 pandemic (yes vs. no), and respondents’ yearly income (< $25 K, $25–$49 K, $50–$99 K, and ≥ 100 K).

Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were presented for numeric variables while frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. For descriptive analysis, t-test, Fisher’s exact, and Chi-squared analyses were used to test the differences and associations of demographics and psycho-social risks with alcohol misuse and binge drinking. Given the prevalence of alcohol misuse, multivariable log-binominal regression analyses were conducted to assess the association of demographic factors and psycho-social factors such as substance use, depression symptom severity, and resident perception of community policing with alcohol misuse and binge drinking, after adjusting for age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Adjusted prevalence rates (aPRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. Data were cleaned and analyzed using STATA version 17.

Ethical Considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy, The City University of New York. All participants provided an online consent form before conducting the survey.

Results

Demographic Factors, Alcohol Misuse, and Binge Drinking

Of the 398 residents, the mean age was 33.8 (SD = 8.9) with most ranging from 30 to 39 years old (49.0%). More than half were female (57.3%) and a third was white individuals (32.2%). The majority of participants (90.5%) were born in the USA and approximately two-thirds (65.1%) were married. Most respondents reported living with 3–8 people (76.9%) and having at least associate’s or college’s degree or higher (68.0%). Nearly 17.0% experienced unemployment and 66.3% had work changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondent’s annual income mostly ranged from $25 K to $49 K (51.3%; Table 1).

In bivariate analyses, demographic factors associated with alcohol misuse and binge drinking during the pandemic included younger people, being males, being white, having associate’s or college’s degree, having work changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and respondents with high annual income.

Alcohol Consumption before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Approximately 42.7% of residents reported drinking alcohol before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in NYC and 69.1% reported alcohol use during the pandemic (Fig. 1). More than a third initiated or increased alcohol consumption during the pandemic (38.7%). Over half of the residents reported alcohol misuse (52.3%) and binge drinking (57.0%) during the pandemic. Among those who reported engaging in binge drinking, 38.9% reported infrequent binge drinking with less than monthly or monthly, and 18.1% reported frequent binge drinking on a weekly, daily, or almost daily basis.

Psycho-social Factors, Alcohol Misuse, and Binge Drinking

Psycho-social risk factors associated with alcohol misuse and binge drinking included higher severity of depression symptomatology, experiencing interpersonal violence, a history of drug use and cigarette smoking, reporting employment insecurity, housing insecurity, food insecurity, and challenges in childcare. In contrast, those who reported higher satisfaction with police were less likely to report alcohol misuse and binge drinking (Table 2).

Associations between Demographic, Psycho-Social Factors, Alcohol Misuse, and Binge Drinking

After adjusting for covariates such as age in years, gender, and race/ethnicity (Table 3), having mild (aPR = 2.32, 95%CI: 1.45, 3.72), moderate (aPR = 2.69, 95%CI: 1.68, 4.30), and severe (aPR = 2.76, 95%CI: 2.67, 4.55) symptoms of depression were associated with at least 132% higher probability of alcohol misuse during the pandemic compared with people without any depressive symptoms. Factors associated with alcohol misuse during the pandemic included a history of drug use (aPR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.36, 1.87) and a history of cigarette smoking (aPR = 1.40, 95%CI: 1.21, 1.62). While residents experiencing housing insecurity were more likely to be identified as alcohol misuse (aPR = 1.48, 95%CI: 1.18, 1.84), those who were more satisfied with community policing (aPR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.95, 0.99) were less likely to experience problematic alcohol use. No significant associations were found of employment insecurity, and food insecurity with alcohol misuse.

Having mild (aPR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.09, 2.23), moderate (aPR = 1.83, 95%CI: 1.28–2.61), and severe (aPR = 2.04, 95%CI: 1.40, 2.97) symptoms of depression were associated with at least 56% greater probability of binge drinking during the pandemic compared with people without any depressive symptoms (Table 3). In addition, factors associated with binge drinking during the pandemic included a history of drug use (aPR = 1.43, 95%CI: 1.25, 1.64) and a history of cigarette smoking (aPR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.23, 1.61). While residents who experienced housing insecurity were more likely to be identified as binge drinking (aPR = 1.31; 95%CI: 1.09, 1.58), no significant associations were found of employment and food insecurity, and perception of community policing with binge drinking.

Interpersonal violence was excluded from the adjusted analysis due to its correlation with depression severity. Similarly, childcare challenge was removed because only 251 participants self-reporting having children. The final models, adjusted for age, gender, and race/ethnicity, showed little change when social-economic status (e.g., being born outside the USA, education, and annual income) was included. Therefore, these variables were excluded to improve the parsimony of the model.

Discussion

Our findings showed that alcohol consumption increased from 42.7% to 69.1% after the pandemic, which is consistent with Barbosa’s 2020 study of a nationally representative sample, which also found an increase in excessive drinking habits among adults [8]. More importantly, we found that approximately 38.7% of residents initiated or increased alcohol use during the pandemic. These findings may imply that Harlem residents used alcohol as a coping strategy for the uncertainties and disruptions of daily life at the peak of the pandemic, which is supporting previous reports [10, 11]. This was compounded by easy access to alcohol during and after lockdown, with Drizly reporting an increase in up to 450% in alcohol delivery sales in NYC just 3 days after bars closed [26]. As COVID-19 vaccination continues and the virus becomes more endemic, the impact of the pandemic on alcohol misuse is important, as alcohol misuse remains a heavy burden on society and on the well-being of individuals affected. It is important to allocate funding for treatment and prevention of alcohol misuse following the pandemic. Our systems must address the economic stressors, mental health including substance use challenges associated with COVID-19 given the widespread prevalence particularly in minoritized communities.

Furthermore, 57.0% of our study population reported binge drinking during the pandemic, with at least six or more drinks consumed on one occasion. Our findings are much higher than the reported New York State data for 2020 (10.8%) in non-Hispanic Black residents. Likewise, prevalence of binge drinking in this sample is higher than in data at the state level, which reports binge drinking in 14.2% of NYC residents [20]. However, this discrepancy should be interpreted with caution due to the essence of small and convenience sampling in our study, which might not be representative for the city or the state as a whole. Notably, 18.1% of our Harlem residents reported frequent binge drinking at least once a week, and 38.9% reported binge drinking at least once a month during the pandemic. Overall, our results highlight concerning findings within Harlem, a neighborhood impacted heavily by the pandemic. Targeted public policies and interventions will be necessary to ameliorate the impact of the pandemic on the frequency of binge drinking.

We found that individuals who experienced housing insecurity had higher risk of both alcohol misuse and binge drinking, which is consistent with previous literature showing that individuals with trouble paying rent or lost housing had significantly increased risk of negative drinking consequences and alcohol dependency [27]. The dual impact of alcohol misuse and housing insecurity leads to a significant burden on individuals, with acute, social, and chronic consequences [28]. Hence, housing instability contributes to worsened mental health and substance use [29]. Interventions to target this at-risk population should improve accessibility to mental health treatment to those with low-income housing in NYC (e.g., affordable, supportive or congregate housing). Our study also highlighted a strong association of depression symptomatology with both alcohol misuse and binge drinking. This association has been well established in research, where a history of major depressive disorder increases the risk of binge drinking and alcohol misuse by two-to-threefold, and vice versa [30, 31]. During the pandemic, this relationship became more prominent, as individuals were more likely to use alcohol as a coping strategy for the stressors created by COVID-19, such as child care challenges, social isolation, and income insecurity [32]. This highlights the importance of integrating treatment for alcohol misuse with mental health interventions as these problems are intertwined. For instance, integration of alcohol misuse screening and intervention within primary care settings has been proven effective in Washington state, with an increase of 50.0% in diagnosis of alcohol use disorder and 54.0% increase in treatment [33].

Both drug use and history of smoking were associated with alcohol misuse and binge drinking in this study, consistent with established literature showing that nicotine use and drug use predicted ethanol consumption and vice versa [34]. Concurrent use of alcohol and nicotine makes it more difficult for individuals to respond to treatment of alcohol use disorders [35] and smoking cessation and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [36]. It is important to screen for alcohol misuse and nicotine/drug use to guide appropriate intervention. On a positive note, our findings show that higher police satisfaction was associated with decreased risk of alcohol misuse in Harlem. Other studies have also shown that adequate police presence and perception of the police force can mitigate risk of alcohol use in the younger population [37]. More studies are needed to evaluate how police perception impacts alcohol misuse and binge drinking among adults. Additionally, it is important for public policy and public health interventions to focus on strengthening the relationship of the police force with these at-risk neighborhoods to reduce the impact of alcohol use within the city.

Our findings should be interpreted in the light of study limitations. First, this study was conducted in Harlem with a predominantly Black population and collected its data via a convenience sample. Hence, these results may not be representative of the New York population as a whole. Yet, these findings highlighted the importance of urgent public health issues among the most vulnerable population during the pandemic. Second, alcohol consumption–related indicators are self-reported without face-to-face surveys, where participants could interpret the questionnaire differently and social desirability bias could be present. Yet, the online survey can be an effective way to gather a sufficiently large sample size during the pandemic, and more importantly, our main findings (e.g., its trend on alcohol consumptions) closely resemble prior citywide and statewide reports. Lastly, our study team solicited expert opinions to develop the perception of community policing scale to examine its association with alcohol misuse and binge drinking. While this is the initial scale employed to assess community policing perceptions, its Cronbach’s alpha was low at 0.41. Further research of this scale is needed in other populations to test the internal consistency as well as evaluate the validity by using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis.

Conclusion

Our study shows a concerning escalation in alcohol consumption throughout Harlem before and during the pandemic, with a high prevalence of initiating or increasing alcohol use during the pandemic. These findings imply that Harlem residents may have resorted to alcohol use as a coping mechanism to deal with the impacts of depression and social stressors. Given the positive association between psycho-social factors (e.g., depression, anxiety, other substance use, and housing insecurity) with alcohol misuse and binge drinking, the implications hint at a concerning burden on New York and Harlem that is associated with the stress and impact of COVID-19. It will be important to direct public health measures and policies toward not just alcohol misuse, but its psycho-social factors. Future interventions are necessary to screen not only for alcohol use, but for these other disorders such as mental health and substance abuse to allow a multifaceted approach to mitigate the burden of alcohol misuse on society.

Data availability

Aggregated datasets provided upon request from the corresponding author.

References

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Understanding alcohol use disorder. 2021. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-alcohol-use-disorder. Accessed 10 Jan 2023.

Griswold MG, et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015–35.

Charlet K, Heinz A. Harm reduction-a systematic review on effects of alcohol reduction on physical and mental symptoms. Addict Biol. 2017;22(5):1119–59.

Collins SE. Associations between socioeconomic factors and alcohol outcomes. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):83–94.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Deaths involving alcohol increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2022. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/news-events/research-update/deaths-involving-alcohol-increased-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 1 Jan 2023.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National survey on drug use and health. 2019. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health. Accessed 29 Apr 2022.

Saloner B, Cook BL. Blacks and Hispanics are less likely than Whites to complete addiction treatment, largely due to socioeconomic factors. Health Aff. 2013;32(1):135–45.

Barbosa C, Cowell AJ, Dowd WN. Alcohol consumption in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J Addict Med. 2021;15(4):341–4.

Witteveen D, Velthorst E. Economic hardship and mental health complaints during COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(44):27277–84.

Romano I, et al. Substance-related coping behaviours among youth during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Behav Rep. 2021;14:100392–2.

MacMillan T, et al. Exploring factors associated with alcohol and/or substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021; 1–10.

Rodriguez LM, Litt DM, Stewart SH. Drinking to cope with the pandemic: the unique associations of COVID-19-related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addict Behav. 2020;110:106532.

Hackbarth DP, et al. Collaborative research and action to control the geographic placement of outdoor advertising of alcohol and tobacco products in Chicago. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(6):558–67.

Lee JP, et al. What explains the concentration of off-premise alcohol outlets in Black neighborhoods? SSM Popul Health. 2020;12:100669.

New York University Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. Central Harlem MN10, in Neighborhood profiles. New York, NY; 2022. Available from: https://furmancenter.org/neighborhoods/view/central-harlem. Accessed 4 Apr 2023.

New York University Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. East Harlem MN11, in Neighborhood profiles. New York, NY; 2022. Available from: https://furmancenter.org/neighborhoods/view/east-harlem . Accessed 4 Apr 2023.

The City of New York. In 2020 NeON Summer served the neighborhoods hardest-hit by COVID-19. 2020. Available from: https://www.nyc.gov/site/neon/programs/covid-neighborhoods.page . Accessed 1 Jan 2023.

CUNY Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy. Harlem COVID-19 Survey – January 2022. New York, NY; 2022. Available from: https://sph.cuny.edu/research/covid-19-surveyjanuary-2022/harlem-covid-19-survey-january-2022/. Accessed 3 Mar 2023.

King L, et al. Community Health Profiles 2015, Manhattan Community District 11: East Harlem; 2015;11(59):1–16. New York, NY; 2015. Available from: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chpmn11.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2023.

Balu RK, et al. Binge and heavy drinking. New York State BRFSS Brief., No. 2022-24. Albany, NY: New York State Department of Health, Division of Chronic Disease Prevention, Bureau of Chronic Disease Evaluation and Research; 2022. Available from: https://health.ny.gov/statistics/brfss/reports/docs/2224_bingeheavydrinking.pdf . Accessed 4 Apr 2023.

Arellano-Anderson J, Keuroghlian AS. Screening, counseling, and shared decision making for alcohol use with transgender and gender-diverse populations. LGBT Health. 2020;7(8):402–6.

Bush K, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol use disorders identification test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–95.

Saunders JB, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804.

Kroenke K, et al. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–21.

Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49.

Movendi International. How COVID-19 affects alcohol, advertising industries. 2020. Available from: https://movendi.ngo/news/2020/03/27/how-covid-19-affects-alcohol-advertising-industries/. Accessed 13 Oct 2022.

Murphy RD, Zemore SE, Mulia N. Housing instability and alcohol problems during the 2007–2009 US recession: the moderating role of perceived family support. J Urban Health. 2014;91(1):17–32.

Pauly B, et al. “There is a place”: impacts of managed alcohol programs for people experiencing severe alcohol dependence and homelessness. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):70.

Chikwava F, et al. Patterns of homelessness and housing instability and the relationship with mental health disorders among young people transitioning from out-of-home care: retrospective cohort study using linked administrative data. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0274196.

Crum RM, et al. The association of depression and problem drinking: analyses from the Baltimore ECA followup study. Epidemiologic catchment area. Addict Behav. 2001;26(5):765–73.

Rodgers B, et al. Non-linear relationships in associations of depression and anxiety with alcohol use. Psychol Med. 2000;30(2):421–32.

Wardell JD, et al. Drinking to cope during COVID-19 pandemic: the role of external and internal factors in coping motive pathways to alcohol use, solitary drinking, and alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020;44(10):2073–83.

Bobb JF, et al. Evaluation of a pilot implementation to integrate alcohol-related care within primary care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(9):1030.

Bien TH, Burge R. Smoking and drinking: a review of the literature. Int J Addict. 1990;25(12):1429–54.

Bold KW, et al. Smoking characteristics and alcohol use among women in treatment for alcohol use disorder. Addict Behav. 2020;101:106137.

Whitfield JB, et al. Effects of high alcohol intake, alcohol-related symptoms and smoking on mortality. Addiction. 2018;113(1):158–66.

Lipperman-Kreda S, Paschall MJ, Grube JW. Perceived local enforcement, personal beliefs, and underage drinking: an assessment of moderating and main effects. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(1):64–9.

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by the City University of New York Interdisciplinary Research Grant (IRG 2841); NIH Transformative Research to Address Health Disparities & Advance Health Equity Initiative (U01OD033245); and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Systems for Action (RWJF 79174) (PI: Victoria K. Ngo).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Luisa N. Borrell and Victoria K. Ngo shared senior authorship.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Vu, T.T., Dario, J.P., Mateu-Gelabert, P. et al. Alcohol Misuse, Binge Drinking, and their Associations with Psychosocial Factors during COVID-19 among Harlem Residents in New York City. J Urban Health 100, 638–648 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00738-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00738-7