Abstract

Background

About 20% of patients with renal cell carcinoma present with non-clear cell histology (nccRCC), encompassing various histological types. While surgery remains pivotal for localized-stage nccRCC, the role of cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) in metastatic nccRCC is contentious. Limited data exist on the role of CN in metastatic nccRCC under current standard of care.

Objective

This retrospective study focused on the impact of upfront CN on metastatic nccRCC outcomes with first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor (IO) combinations or tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) monotherapy.

Methods

The study included 221 patients with nccRCC and synchronous metastatic disease, treated with IO combinations or TKI monotherapy in the first line. Baseline clinical characteristics, systemic therapy, and treatment outcomes were analyzed. The primary objective was to assess clinical outcomes, including progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Statistical analysis involved the Fisher exact test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, analysis of variance, Kaplan–Meier method, log-rank test, and univariate/multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models.

Results

Median OS for patients undergoing upfront CN was 36.8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 24.9–71.3) versus 20.8 (95% CI 12.6–24.8) months for those without CN (p = 0.005). Upfront CN was significantly associated with OS in the multivariate Cox regression analysis (hazard ratio 0.47 [95% CI 0.31−0.72], p < 0.001). In patients without CN, the median OS and PFS was 24.5 (95% CI 18.1–40.5) and 13.0 months (95% CI 6.6–23.5) for patients treated with IO+TKI versus 7.5 (95% CI 4.3–22.4) and 4.9 months (95% CI 3.0–8.1) for those receiving the IO+IO combination (p = 0.059 and p = 0.032, respectively).

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates the survival benefits of upfront CN compared with systemic therapy without CN. The study suggests that the use of IO+TKI combination or, eventually, TKI monotherapy might be a better choice than IO+IO combination for patients who are not candidates for CN regardless of IO eligibility. Prospective trials are needed to validate these findings and refine the role of CN in current mRCC management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma of non-clear cell histology undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy prior to systemic therapy have better outcomes compared with those treated with systemic therapy alone. |

For patients who are not candidates for cytoreductive nephrectomy, immunotherapy plus tyrosine kinase inhibitor combination or, eventually, tyrosine kinase inhibitor monotherapy might be preferred. |

1 Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents one of the most prevalent urogenital malignancies with increasing incidence in developed countries [1]. Clear cell RCC is the predominant histological type, accounting for about 80% of all RCC cases. According to the current histopathological classification of non-clear cell RCC (nccRCC), accounting for the remaining 20% of RCC cases, it comprises several distinct entities [2]. Nonetheless, while surgery remains the pivotal therapeutic strategy for localized-stage RCC, the question regarding the role of cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) in the context of mRCC continues to be a subject of considerable contention. In the previous era of cytokine therapy, CN followed by cytokine therapy used to be the standard of care. This approach was based on two prospective randomized clinical trials [3, 4]. However, substantial progress in systemic therapies for mRCC has been changing this paradigm. The cytokine therapy era was followed by the era of targeted therapies, based on the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Now, we are moving forward into the era of immunotherapy combinations, where the front-line therapy is based on immuno-oncology (IO) combinations with two immune checkpoint inhibitors (IO+IO) or a combination of IO and TKIs (IO+TKI). The results of a prospective randomized trial, CARMENA, suggest that sunitinib alone is non-inferior to CN followed by sunitinib in mRCC with intermediate or poor prognosis according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center prognostic model [5]. In contrast, several retrospective studies showed superior outcomes of patients with mRCC undergoing upfront CN [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. When focusing on the role of CN in the current standard of care based on first-line IO combinations, the data are limited. Although several retrospective studies suggest improved outcomes in patients who underwent CN, there are no available data from prospective randomized trials that are currently in progress [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Furthermore, the question of optimal timing of CN (upfront vs deferred) has been a subject of debate.

Importantly, the vast majority of data on CN currently available are derived from studies mainly focused on clear cell RCC or an unselected mRCC population, where nccRCC represented only small patient cohorts. Thus, the role of CN in patients with mRCC of non-conventional histological types remains highly underexplored. In the present retrospective study, we focused on the impact of upfront CN on the outcomes of patients with metastatic nccRCC treated with IO combinations or TKI monotherapy as a first-line systemic therapy.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Population

The study included patients with nccRCC, and synchronous metastatic disease, treated with first-line IO combinations (1 January, 2016 to 1 October, 2023) or TKI monotherapy (1 January, 2008 to 1 January, 2017) from 47 cancer centers. All included patients had known baseline clinicopathological characteristics including the prognostic group according to the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) criteria [22], previous upfront CN, and the type and duration of systemic therapy.

Clinical data were retrospectively extracted at each participating center, from the patients’ medical records. First-line therapy was continued until evidence of clinical and/or radiological progression according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) Version 1.1 criteria [23], unacceptable toxicities, or death. Computed tomography and laboratory tests were performed following current clinical guidelines and standard local procedures.

The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice and has been designed with the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki on human experimentation. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the coordinating center (Marche Region—2021-492, Study Protocol “ARON-1 Project” NCT05287464) and by the institutional review boards of the international participating centers. Informed consent with subsequent analysis of the follow-up data was obtained from all participants.

2.2 Statistical Analysis

Baseline clinical characteristics were summarized with descriptive statistics and the comparisons between groups were performed using the Fisher exact test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and an analysis of variance. Overall survival (OS) was determined from the date of the first-line treatment initiation until the date of death of any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was determined from the date of the first-line treatment initiation until the date of progression or death of any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients in whom the terminal event had not occurred were censored at the date of the last follow-up. Overall survival and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and point estimates were accompanied by two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The log-rank test was used for the assessment of statistical significance of the differences in OS and PFS. To identify independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models were performed. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using the MedCalc Version 19.6.4 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).

3 Results

3.1 Study Population

In total, the ARON-1 study enrolled 4211 patients with RCC. We identified 369 (8.7%) patients with metastatic nccRCC; of those, 221 presented with synchronous metastatic disease at diagnosis and were included in the present study (Fig. S1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]); 111 patients (50%) underwent upfront CN followed by first-line systemic therapy (CN group) while 110 patients (50%) were treated with systemic therapies without CN (no-CN group).

The median age was 64 years (range 25−89 years). Tumor histology was papillary in 118 cases (53%), chromophobe in 26, unclassified in 25, MiT family translocation in 9, tubolocystic in 4, fumarate hydratase deficient in 4, Bellini duct in 4, medullary in 3, eosinophilic solid and cystic in 3, mucinous tubular spindle cell in 3, and thyroid-like follicular in 2 cases. The lung was the most common metastatic site occurring in 128 patients (58%). Fifty-four patients (24%) presented with only one site of metastases, while 167 (76%) had two or more metastatic sites.

Baseline clinical and pathological characteristics of patients according to CN are summarized in Table 1. The only characteristic that differs significantly between the two groups is the distribution of the IMDC risk group (p = 0.002); indeed, nephrectomized patients had fewer poor-risk and more intermediate-risk individuals compared with those not undergoing CN. In addition, no differences were observed in the clinical characteristics of patients according to the type of first-line systemic therapy (Table 2). The median follow-up time in the overall study population was 26.6 months (95% CI 13.4−78.5); 30.2 months (95% CI 20.7–49.8) for patients receiving TKI monotherapy, 23.8 months (95% CI 12.0–51.7) for IO+TKI, and 25.2 months (95% CI 17.8–80.9) for those receiving IO+IO (p = 0.561).

3.2 OS and PFS

The median OS was 36.8 months (95% CI 24.9–71.3) for patients who underwent CN versus 20.8 months (95% CI 12.6–24.8) for those without CN (p = 0.005, Fig. 1). The benefit of upfront CN was confirmed in both IMDC risk groups (intermediate risk: 41.7 months, 95% CI 26.9–72.3 vs 24.5 months 95% CI 20.8–31.3, p = 0.046; poor risk: 27.7 months, 95% CI 11.9–35.3 vs 9.2 months, 95% CI 7.5–22.1, p = 0.022; Fig. 1). No significant difference in PFS was found between patients who underwent CN or not (11.7 months, 95% CI 6.5–80.0 vs 6.6 months, 95% CI 6.0–45.7, p = 0.229), with a 1-year PFS rate of 48% vs 37% (p = 0.117). Similarly, no significant difference in PFS was found between the CN and no-CN groups in both intermediate-risk patients (12.2 months, 95% CI 8.3–80.0 vs 8.1 months, 95% CI 6.1–45.7, p = 0.527) and poor-risk patients (8.1 months, 95% CI 3.2–22.7 vs 6.1 months, 95% CI 4.8–8.7, p = 0.390).

Further, we stratified patients by metastatic sites. Overall survival was significantly longer in the CN subgroup in the patients with lung (41.7 months, 95% CI 27.7–116.8 vs 28.8 months, 95% CI 9.3–30.0, p < 0.001, Fig. 2), bone (41.7 months, 95% CI 24.9–92.3 vs 12.6 months, 95% CI 9.2–30.0, p = 0.004, Fig. 2), or liver metastases (36.8 months, 95% CI 19.7–93.4, vs 8.1 months, 95% CI 6.4–24.5, p = 0.017, Fig. 2). The favorable impact of CN was observed in both patients with one metastatic site (median OS: 71.3 months, 95% CI 35.3–71.3 vs 29.4 months, 95% CI 12.6–40.5, p = 0.046, Fig. 2) or those with two or more metastatic sites (median OS: 28.8 months, 95% CI 23.9–116.8 vs 16.7 months, 95% CI 9.3–22.4, p = 0.002, Fig. 2).

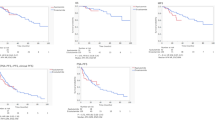

3.3 Comparison of OS and PFS Between Immune-Based Combinations and TKI Monotherapy According to Upfront CN

The median OS was 31.1 (95% CI 20.8–40.5) for patients receiving IO+TKI, 19.7 months (95% CI 7.3–28.8) for IO+IO, and 26.9 months (95% CI 22.1–36.8) for those receiving TKI monotherapy (p = 0.236, Fig. 3A). The median PFS was 15.8 months (95% CI 12.7–22.7) for IO+TKI, 8.1 months (95% CI 4.1–47.6) for IO+IO, and 6.5 months (95% CI 5.340.0) for those receiving TKI monotherapy (p = 0.037, Fig. 3B).The survival according to IMDC risk can be seen in the ESM.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival and overall survival according to the type of first-line therapy stratified by upfront cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN). Comparison between immuno-oncology (IO) combinations containing tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) plus IO (TKI+IO) vs a combination of two IO agents (IO+IO) vs TKI monotherapy (TKI) for the overall patient population (A, B), patients who underwent CN (C, D), and those without CN (E, F)

In patients who underwent CN, the median OS was not reached for both the types of IO combinations and 26.9 months (95% CI 23.5–41.7) for TKI monotherapy (p = 0.080, Fig. 3C). The median PFS was 22.7 months (95% CI 12.3–23.5) versus 11.9 months (95% CI 3.9–47.6) for those treated with IO+TKI versus IO+IO versus TKI monotherapy, respectively (p = 0.005, Fig. 3D).

In patients without CN, the median OS was 24.5 (95% CI 18.1–40.5) for patients receiving IO+TKI, 7.5 (95% CI 4.3–22.4) for IO+IO, and 22.1 months (95% CI 12.6–30.0) for those treated with TKI monotherapy (p = 0.065, Fig. 3E). The median PFS was 13.0 months (95% CI 6.6–23.5) for patients treated with IO+TKI, 4.9 months (95% CI 3.0–8.1) for those receiving the IO+IO combination, and 6.5 months (95% CI 5.0–45.7) for those receiving TKI monotherapy (p = 0.033, Fig. 3F).

3.4 Univariate and Multivariate Cox Analyses

Upfront CN was significantly associated with OS in both univariate (HR 0.48 [95% CI 0.31−0.72], p < 0.001) and multivariate (HR 0.47 [95% CI 0.31−0.72], p < 0.001) Cox regression analyses. Other significant prognostic factors for OS were IMDC risk group and the number of metastatic sites in both univariate and multivariate models. Otherwise, the IMDC risk group, bone metastases, and the choice between TKI monotherapy and IO combinations were significant predictors of PFS in the univariate analysis and subsequently the presence of bone metastases and the choice of first-line therapy confirmed their prognostic role in the multivariate analysis. The results of Cox regression analyses are listed in Table 3.

4 Discussion

The results of our retrospective study suggest a superior OS for patients with synchronous metastatic nccRCC undergoing upfront CN followed by systemic therapy regardless of whether with IO combination regimens or TKI monotherapy as compared with those who did not undergo surgery. In the current era of IO combinations, the role of CN is more relevant than ever and a subject of ongoing discussion. Nevertheless, the use of CN in mRCC has remained substantially stable for the last decades: more than 85% of patients included in randomized clinical trials and expanded access programs published from 2003 to 2019 had undergone previous nephrectomy before systemic therapy initiation, which means that current evidence driving the clinical practice, is mainly based on a nephrectomized population and supports the use of CN also in the metastatic setting [24]. As the systemic treatment with cytokines proved benefit in patients with mRCC, studies evaluating the addition of CN in patients with synchronous metastatic disease started to emerge. A combined analysis of two randomized trials conducted in the era of cytokine first-line therapy underlined a 31% reduction in the risk of death in patients undergoing surgery [25]. Since then, CN has become a pivotal weapon in the spectrum of treatment for patients with mRCC with good performance status and a limited burden of disease. In the following TKI era, two parallel prospective clinical trials, CARMENA (Cancer du Rein Metastatique Nephrectomie et Antiangiogéniques) and SURTIME (Immediate Surgery or Surgery After Sunitinib Malate in Treating Patients With Metastatic Kidney Cancer), explored the role of CN [5, 26]. The CARMENA trial was a non-inferiority study evaluating the upfront CN strategy, followed by systemic therapy with sunitinib compared to a sunitinib without CN approach. The analysis showed that sunitinib alone was not inferior to the combination of surgery followed by sunitinib in terms of OS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.89) and PFS (HR 0.82) [5]. Stratifying patients according to IMDC risk factors, patients with one risk factor seemed to benefit from surgery, while in patients with at least two risk factors for CN this appeared to be detrimental in terms of survival [27]. The parallel SURTIME trial compared upfront surgery followed by sunitinib therapy with deferred CN after a 3-month sunitinib treatment. No significant difference in PFS was found between the two strategies, while median OS was significantly longer in the arm with deferred CN (32.4 months vs 15.0 months, HR 0.57, p = 0.03). In addition, the SURTIME study highlighted that patients with premature progressive disease do not seem to benefit from surgery and have a worse overall prognosis [26].

To date, the treatment of mRCC has changed substantially. However, the data supporting CN in the modern era of IO combination therapies only come from retrospective analyses. The available data appear to be consistent, suggesting a positive impact of CN on OS of patients with mRCC, while it is performed before or after the initiation of systemic therapy represented by IO+IO or IO+TKI combinations [21, 28, 29].

A recent evidence-based meta-analysis of eight studies including 2397 patients with mRCC treated with various IO therapies (i.e., nivolumab+ipilimumab, nivolumab monotherapy, or interferon-alpha) confirmed the positive survival impact of CN (HR 0.53, p < 0.0001) [30].

Less is known regarding the potential difference between upfront and deferred surgery. Another meta-analysis of nine studies conducted by Li et al., focusing on this point, found a longer OS for patients undergoing deferred CN compared with those undergoing upfront surgery (HR 0.71, p = 0.003) in the overall population of patients with mRCC. However, particularly in patients receiving IO as a systemic therapy, there was no difference in OS between the two CN strategies (p = 0.41) [31]. Similar results came from a recent small prospective randomized study conducted by Shen et al.’s group enrolling 84 patients with mRCC, which reported no OS difference between the two CN strategies (HR 0.814), although deferred CN appeared to improve PFS in patients receiving nivolumab (HR 0.50) [32].

According to current international guidelines for mRCC, upfront CN should be considered only in selected patients, while it should be deferred after IO combination therapy initiation, in those with a clinical response. Patients with a poor-risk prognosis according to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center/IMDC should not be considered for CN [33].

Beyond providing data for the role of CN in the era of IO combinations, our analysis aimed at exploring a population for whom data are strongly lacking: patients affected by nccRCC. In patients with rare non-clear cell histology types, there is very limited, typically retrospective, evidence supporting CN. Three comparable registry-based assessments were conducted within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, involving 951 patients (2000–9), 851 patients (2001–14), and 1573 patients (2006–15) with nccRCC, respectively. The results were a consistent and observed reduction in mortality rates for patients undergoing CN (cancer-specific mortality rate: HR 0.62, p < 0.001, HR 0.38, p < 0.001 and overall mortality rate: HR 0.3, p < 0.001 in the analysis by Aizer et al., Marchioni et al., and Luzzago et al., respectively). Data on the type of systemic therapy received were not available and, with regard to the considered time frame (2000–15), we assumed that the patients were not treated with first-line IO combinations [34,35,36]. Similarly, a Korean retrospective analysis including 156 patients with nccRCC highlighted that patients undergoing CN reported longer cancer-specific survival than those without CN (median cancer-specific survival: 30 months vs 6 months, p < 0.0001). In their study, no patient received first-line IO therapy [37]. Last, the group of Riveros retrospectively analyzed the outcomes of 594 patients with papillary RCC receiving IO or IO+TKI combinations. Their study showed that patients undergoing CN in addition to systemic therapy experienced longer OS (HR 0.59) [38].

Consistent with what has been reported in the literature, our data support the positive prognostic role of upfront CN in patients with metastatic nccRCC, revealing a statistically significant association with longer OS both in univariate and multivariate analysis, despite the different distribution of IMDC risk groups between nephrectomized and non-nephrectomized patients. Moreover, CN was associated with longer OS in every subgroup of patients, stratified according to IMDC risk groups, and by the type or number of metastatic sites (including patients with liver metastases). In our study population, the use of IO combination regimens compared to TKI monotherapy was associated with longer PFS (confined to IMDC intermediate-risk patients) but without differences in terms of OS, indicating no difference in the prognostic impact of CN based on the type of systemic treatment (TKI monotherapy vs IO combinations). Furthermore, both IO+TKI and TKI monotherapy showed superior OS compared with the IO+IO combination. No differences in PFS were observed according to upfront CN, suggesting that the prognostic role of CN may be independent of the benefit obtained from first-line treatment in terms of disease control. Interestingly, among patients treated with IO combinations, those treated with IO+TKI showed both longer OS and PFS compared with patients treated with the IO+IO combination, especially for patients who did not undergo CN. This observation may support the hypothesis that patients with the primary tumor in place may have a greater need for the anti-angiogenic activity of TKIs. Additionally, our results suggest that TKI monotherapy is still an acceptable front-line systemic treatment for patients with nccRCC, particularly for those who are not candidates for the IO+TKI combination. However, the results of these subgroup analyses in the present study should be taken with caution because of the limited number of patients in the specific subgroups and the selected population of patients with synchronous metastatic disease.

Our study has some limitations that should be noted. These include the retrospective design, the absence of a comparison between upfront and deferred CN, the absence of a central pathology review, and the relatively small sample size. We have to point out that the high number of intermediate-risk patients in the CN group and poor-risk patients in the non-CN group and a consequent selection bias may raise uncertainty regarding the difference in OS observed in this study.

Several ongoing prospective clinical trials aim to clarify the role of CN in the context of IO combinations: the Cyto-KIK trial (NCT04322955) is testing a combination with nivolumab+cabozantinib, PrimerX (NCT05941169) immunotherapy, while the PROBE trial (NCT04510597) and NORDIC-SUN trial (NCT03977571) are testing any currently available combination. All these trials plan to include patients with nccRCC. Hopefully, these results will harden the evidence and elucidate the role of CN in the future.

5 Conclusions

Our analysis adds strength to the current argument for incorporating CN into a systemic therapy for metastatic nccRCC. When feasible, upfront CN should also be considered in selected patients with non-clear cell histological types of RCC as it is associated with longer OS irrespective of the choice of first-line systemic treatment. The use of IO+TKI combination or, eventually, TKI monotherapy might be a better choice than IO+IO combination for patients who are not candidates for CN regardless of IO eligibility.

References

Znaor A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Laversanne M, Jemal A, Bray F. International variations and trends in renal cell carcinoma incidence and mortality. Eur Urol. 2015;67:519–30.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 24 Apr 2024.

Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, Bearman SI, Roy V, McGrath PC, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1655–9.

Mickisch GH, Garin A, van Poppel H, de Prijck L, Sylvester R, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Genitourinary Group. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:966–70.

Méjean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, Colas S, Beauval JB, Bensalah K, et al. Sunitinib alone or after nephrectomy in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. New Engl J Med. 2018;379:417–27.

You D, Jeong IG, Ahn JH, Lee DH, Lee JL, Hong JH, et al. The value of cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the era of targeted therapy. J Urol. 2011;185:54–9.

Graham J, Wells JC, Donskov F, Lee JL, Fraccon A, Pasini F, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in metastatic papillary renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol Oncol. 2019;2:643–8.

Klatte T, Fife K, Welsh SJ, Sachdeva M, Armitage JN, Aho T, et al. Prognostic effect of cytoreductive nephrectomy in synchronous metastatic renal cell carcinoma: acomparative study using inverse probability of treatment weighting. World J Urol. 2018;36:417–25.

Day D, Kanjanapan Y, Kwan E, Yip D, Lawrentschuk N, Davis ID, et al. Benefit from cytoreductive nephrectomy and the prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Intern Med J. 2016;46:1291–7.

Choueiri TK, Xie W, Kollmannsberger C, North S, Knox JJ, Lampard JG, et al. The impact of cytoreductive nephrectomy on survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy. J Urol. 2011;185:60–6.

Heng DY, Wells JC, Rini BI, Beuselinck B, Lee JL, Knox JJ, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol. 2014;66:704–10.

de Groot S, Redekop WK, Sleijfer S, Oosterwijk E, Bex A, Kiemeney LA, et al. Survival in patients with primary metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib with or without previous cytoreductive nephrectomy: results from a population-based registry. Urology. 2016;95:121–7.

Poprach A, Holanek M, Chloupkova R, Lakomy R, Stanik M, Fiala O, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy and overall survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy: data from the National Renis Registry. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:2911.

Singla N, Hutchinson RC, Ghandour RA, Freifeld Y, Fang D, Sagalowsky AI, et al. Improved survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the contemporary immunotherapy era: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. Urol Oncol. 2020;38(604):e9-17.

Bakouny Z, El Zarif T, Dudani S, Connor Wells J, Gan CL, Donskov F, et al. Upfront cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors or targeted therapy: an observational study from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol. 2023;83:145–51.

Gross EE, Li M, Yin M, Orcutt D, Hussey D, Trott E, et al. A multicenter study assessing survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy with and without cytoreductive nephrectomy. Urol Oncol. 2023;41(51):e25-51.e31.

Rebuzzi SE, Signori A, Banna GL, Gandini A, Fornarini G, Damassi A, et al. The prognostic value of the previous nephrectomy in pretreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving immunotherapy: a sub-analysis of the Meet-URO 15 study. J Transl Med. 2022;20:435.

Yoshino M, Ishihara H, Nemoto Y, Nakamura K, Nishimura K, Tachibana H, et al. Therapeutic role of deferred cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2022;52:1208–14.

Stellato M, Santini D, Verzoni E, De Giorgi U, Pantano F, Casadei C, et al. Impact of previous nephrectomy on clinical outcome of metastatic renal carcinoma treated with immune-oncology: a real-world study on behalf of Meet-URO Group (MeetUro-7b). Front Oncol. 2021;11: 682449.

Ghatalia P, Handorf EA, Geynisman DM, Deng M, Zibelman MR, Abbosh P, et al. The role of cytoreductive nephrectomy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a real-world multi-institutional analysis. J Urol. 2022;208:71–9.

Takemura K, Ernst MS, Navani V, Wells JC, Bakouny Z, Donskov F, et al. Characterization of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma undergoing deferred, upfront, or no cytoreductive nephrectomy in the era of combination immunotherapy: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol Oncol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euo.2023.10.002.

Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Harshman LC, Bjarnason GA, Vaishampayan UN, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:141–8.

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumours: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16.

Mazzaschi G, Quaini F, Bersanelli M, Buti S. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in the era of targeted- and immuno- therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an elusive issue? A systematic review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;160: 103293.

Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, Tangen C, Van Poppel H, Crawford ED. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol. 2004;171:1071–6.

Bex A, Mulders P, Jewett M, Wagstaff J, van Thienen JV, Blank CU, et al. Comparison of immediate vs deferred cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving sunitinib: the SURTIME randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:164–70.

Méjean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, Chevreau C, Bensalah K, Geoffrois L, et al. Sunitinib alone or after nephrectomy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: is there still a role for cytoreductive nephrectomy? Eur Urol. 2021;80:417–24.

Studentova H, Spisarova M, Kopova A, Zemankova A, Melichar B, Student V Jr. The evolving landscape of cytoreductive nephrectomy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:3855.

Song SH, Lee S. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in the age of immunotherapy-based combination treatment. Investig Clin Urol. 2023;64:425–34.

Li KP, Chen SY, Wang CY, Li XR, Yang L. The impact of cytoreductive nephrectomy on survival outcomes in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving immunotherapy: an evidence-based analysis of comparative outcomes. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1132466.

Li KP, He M, Wan S, Chen SY, Wang CY, Li XR. Comparison of upfront versus deferred cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving systemic therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2023;109:3178–88.

Shen XP, Xie M, Wang JS, Guo X. Efficacy of immunotherapy-based immediate cytoreductive nephrectomy vs. deferred cytoreductive nephrectomy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27:5684–91.

Rouprêt M, Seisen T, Birtle AJ, Capoun O, Compérat EM, Dominguez-Escrig JL, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: 2023 update. Eur Urol. 2023;84:49–64.

Aizer AA, Urun Y, McKay RR, Kibel AS, Nguyen PL, Choueiri TK. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic non-clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC). BJU Int. 2014;113:E67-74.

Marchioni M, Bandini M, Preisser F, Tian Z, Kapoor A, Cindolo L, et al. Survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy in metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients: a population-based study. Eur Urol Focus. 2019;5:488–96.

Luzzago S, Palumbo C, Rosiello G, Knipper S, Pecoraro A, Mistretta FA, et al. Association between systemic therapy and/or cytoreductive nephrectomy and survival in contemporary metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:598–607.

Kim JK, Kim SH, Song MK, Joo J, Seo SI, Kwak C, et al. Survival and clinical prognostic factors in metastatic non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy: a multi-institutional, retrospective study using the Korean metastatic renal cell carcinoma registry. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3401–10.

Riveros C, Ranganathan S, Xu J, Chang C, Kaushik D, Morgan M, et al. Comparative real-world survival outcomes of metastatic papillary and clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and combination therapy. Urol Oncol. 2023;41(150):e1-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Open access publishing supported by the National Technical Library in Prague.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Ondrej Fiala received honoraria from Novartis, Janssen, Merck, BMS, MSD, Pierre Fabre, and Pfizer for consultations and lectures unrelated to this project. Sebastiano Buti has received honoraria for speaking at scientific events and advisory roles from AstraZeneca, BMS, Ipsen, Merck, Eisai, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer and research funding from Novartis and Pfizer unrelated to this project. Francesco Massari has received research support and/or honoraria from Astellas, BMS, Janssen, Ipsen, MSD, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Enrique Grande has received honoraria for speaker engagements, advisory roles, or funding of continuous medical education from Adacap, Amgen, Angelini, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blueprint, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caris Life Sciences, Celgene, Clovis-Oncology, Eisai, Eusa Pharma, Genetracer, Guardant Health, HRA-Pharma, Ipsen, ITM-Radiopharma, Janssen, Lexicon, Lilly, Merck KGaA, MSD, Nanostring Technologies, Natera, Novartis, ONCODNA (Biosequence), Palex, Pharmamar, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Genzyme, Servier, Taiho, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and research grants from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Astellas, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper. Ugo De Giorgi services as an advisory/board member of Astellas, Bayer, BMS, Ipsen, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi, has received research grant/funding to the institution from AstraZeneca, Roche, and Sanofi, and travel/accommodations/expenses from AstraZeneca, BMS, Ipsen, Janssen, and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper. Javier Molina-Cerrillo declares consultant, advisory, or speaker roles for Ipsen, Roche, Pfizer, Sanofi, Janssen, and BMS unrelated to this project. Zin W. Myint has received research support from Merck unrelated to the present paper. Ray Manneh Kopp has received research support and/or honoraria from Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Tecnofarma, and Roche unrelated to this project. Jakub Kucharz has received honoraria from Angelini, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, IPSEN, Janssen, Merck MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer, and research funding from Novartis, all unrelated to the present paper. Maria Giuseppa Vitale has received honoraria from Astellas, BMS, MSD, and Ipsen unrelated to this project. Alvaro Pinto has received research support and/or honoraria from Pfizer, Novartis, Ipsen, BMS, Janssen, Astellas, Sanofi, Bayer, Clovis, Roche, MSD, Pierre Fabre, Merck, Bayer, Pharmacyclics, AstraZeneca, Eisai, and Aveo unrelated to this project. Thomas Büttner has received fees for speakers bureau, travel, and accommodation from Astellas, Ipsen, and MSD, all unrelated to the present paper. Carlo Messina has received fees for speakers bureau and advisory board activities from Merck, MSD, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Johnson and Johnson, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baier, and GSK, all unrelated to the present paper. Fernando Sabino M. Monteiro has received research support from Janssen and Merck Sharp Dome and honoraria from Janssen, Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Merck Sharp Dome. All unrelated to the present paper. Ravindran Kanesvaran has received fees for speakers bureau and advisory board activities from Pfizer, MSD, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Amgen, Astellas, and Bayer, all unrelated to this project. Tomáš Büchler has received research support from AstraZeneca, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Merck KGaA, MSD, and Novartis, consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Astellas, Janssen, and Sanofi/Aventis, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Roche, Servier, Accord, MSD, and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper. Jindřich Kopecký has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, MSD, and Ipsen and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureau, manuscript writing, or educational events from Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. All of the above are unrelated to the present paper. Camillo Porta has received honoraria from Angelini Pharma, AstraZeneca, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, and MSD and acted as a Protocol Steering Committee Member for BMS, Eisai, and MSD unrelated to this project. Matteo Santoni has received research support and honoraria from Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ipsen, MSD, Astellas, A.A.A., and Bayer unrelated to the present paper. Aristotelis Bamias, Renate Pichler, Marco Maruzzo, Emmanuel Seront, Fabio Calabrò, Gaetano Facchini, Rossana Berardi, Luigi Formisano, Nicola Battelli, Daniele Santini, and Giulia Claire Giudice have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the coordinating center (Marche Region—2021-492, Study Protocol “ARON-1 Project” NCT05287464) and by the institutional review boards of the international participating centers.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of patient data security but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

Study concept and design: all authors. Acquisition of data: all authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: OF, SB, MS, CG. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: MS. Obtaining funding: none. Administrative, technical, or material support: none. Supervision: CP.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fiala, O., Buti, S., Bamias, A. et al. Real-World Impact of Upfront Cytoreductive Nephrectomy in Metastatic Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated with First-Line Immunotherapy Combinations or Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (A Sub-Analysis from the ARON-1 Retrospective Study). Targ Oncol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-024-01065-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-024-01065-w