Abstract

To examine cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships of psychotropic medications with physical function after menopause. Analyses involved 4557 Women’s Health Initiative Long Life Study (WHI-LLS) participants (mean age at WHI enrollment (1993–1998): 62.8 years). Antidepressant, anxiolytic, and sedative/hypnotic medications were evaluated at WHI enrollment and 3-year follow-up visits. Performance-based physical function [Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)] was assessed at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS visit. Self-reported physical function [RAND-36] was examined at WHI enrollment and the last available follow-up visit—an average of 22 [±2.8] (range: 12–27) years post-enrollment. Multivariable regression models controlled for socio-demographic, lifestyle, and health characteristics. Anxiolytics were not related to physical function. At WHI enrollment, antidepressant use was cross-sectionally related to worse self-reported physical function defined as a continuous (β = −6.27, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −8.48, −4.07) or as a categorical (< 78 vs. ≥ 78) (odds ratio [OR] = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.48, 2.98) outcome. Antidepressant use at WHI enrollment was also associated with worse performance-based physical function (SPPB) [< 10 vs. ≥ 10] (OR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.05, 2.21) at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS visit. Compared to non-users, those using sedative/hypnotics at WHI enrollment but not at the 3-year follow-up visit reported a faster decline in physical function between WHI enrollment and follow-up visits. Among postmenopausal women, antidepressant use was cross-sectionally related to worse self-reported physical function, and with worse performance-based physical function after > 20 years of follow-up. Complex relationships found for hypnotic/sedatives were unexpected and necessitate further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The decline in physical functioning that accompanies aging has detrimental implications for quality of life [1], well-being [2], and independence [3]. Epidemiologic studies of older adults suggest that self-reported and performance-based physical function may be worsened by frequently co-occurring depression [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], anxiety [5, 10, 12,13,14], and sleep disorders [13, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. The impact of anxiety and depression on physical function appears to be complex. For instance, a study of older patients with knee osteoarthritis suggested that while higher anxiety was related to poorer self-reported physical function, neither anxiety nor depression was related to performance-based physical function [9]. By contrast, among community-dwelling adults, ≥ 80 years of age, poor sleep efficiency and frequent waking after sleep onset were negatively associated with walking speed and knee extension strength [21]. A gap exists as to how psychotropic (antidepressants [28,29,30], anxiolytic [12], and sedative/hypnotic [12, 31, 32]) medications that were used to treat depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders may alter physical function. One issue is that psychotropic medications are used for a variety of indications. Nevertheless, they are known to increase the risk of falls and fractures, to slow gait speed, and to promote neurocognitive dysfunction in older populations [33,34,35,36,37]. Antidepressant use has been specifically evaluated in relation to morbidity and mortality risks among postmenopausal women [33,34,35,36,37], with much less known about the health implications of anxiolytic [38] and sedative/hypnotic [38, 39] use after menopause. There is limited evidence linking any of the psychotropic medications to physical function among older adults [28,29,30, 40], in general, and in postmenopausal women [32], in particular. Most available studies have ≤ 10 years of follow-up and assessed psychotropic medication use and physical function at a single time point. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, and specifically, the WHI Long Life Study (WHI-LLS), allows us to examine cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships of antidepressant, anxiolytic, and sedative/hypnotic medication use to physical function among postmenopausal women with > 20 years of follow-up. Use of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and sedative/hypnotics may be associated with poorer physical function not only because they are considered a proxy for underlying depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders but also because they may reflect level of disease severity and can result in side-effects that are detrimental to physical function [41]. In this study, we hypothesized that psychotropic medication use is related to poorer physical function at baseline and over time among postmenopausal women.

Methods

Data sources

The WHI is a long-term study focused on strategies for preventing heart disease, breast, and colorectal cancers as well as osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. The WHI study design, eligibility criteria, recruitment methods, and measurement protocols are described elsewhere [42, 43]. Briefly, the WHI collected data on a multiethnic sample of postmenopausal women who were recruited and enrolled between 1993 and 1998 at 40 geographically diverse clinical centers (24 states and the District of Columbia) in the United States. The WHI study received institutional review board approval with informed consent from all participating clinical centers. WHI-Clinical Trials (n = 68,132) and the WHI-Observational Study (n = 93,676) are two components of the WHI with a combined enrollment of 161,808 participants. Whereas WHI-CTs evaluated outcomes of menopausal hormone therapy (Hormone Therapy [HT] Trials), calcium and vitamin D supplementation ([CaD] Trial), and a low-fat eating pattern (Dietary Modification Trial), the WHI-OS evaluated causes of morbidity and mortality in postmenopausal women. At enrollment (1993–1998), WHI participants, 50–79 years of age, completed the same self-administered questionnaire covering demographics, general health, clinical and anthropometric characteristics, functional status, healthcare behaviors, reproductive, medical, and family history, personal habits, thoughts and feelings, therapeutic class of medication, hormones, supplements, and dietary intake, and several of these characteristics were assessed at later follow-up times. The main analyses for this paper were performed using data on WHI participants who enrolled in the WHI-LLS which was conducted in 2012–2013. The WHI-LLS involves a one-time, in-person, visit for collecting phlebotomy, anthropometry, and objective physical function measures in a subset of WHI participants. The WHI-LLS included former participants of the WHI HT, as well as African American and Hispanic women. Women who resided in an institution or were unable to provide informed consent due to dementia were excluded from the WHI-LLS. Of 14,081 WHI participants who were eligible for the WHI-LLS, 7875 women, 63–99 years of age, successfully completed at-home visits between March 2012 and May 2013 [44,45,46]. An additional sub-cohort of WHI-CT participants (≥ 65 years of age at enrollment) had performance-based physical function tests at enrollment (1993–1998), 1 year, 3 years, and 6 years follow-up visits [47]. This sub-cohort provided the opportunity to conduct more detailed longitudinal analyses of hypothesized relationships between psychotropic medications and physical function. This project was determined as exempt research by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute on Aging.

Study variables

Psychotropic medications

WHI participants were instructed to bring prescription and non-prescription medication containers at enrollment (1993–1998) and 3-year follow-up visits. With respect to medications used for > 2 weeks, drug names and doses were entered into a medications database and assigned therapeutic class codes using the Master Drug Data Base (MDDB: Medi-Span, Indianapolis, IN; Medi-Span software: First DataBank, Inc., San Bruno, CA). A series of dichotomous (“yes” or “no”) variables were defined for psychotropic (antidepressants, anxiolytics, sedative/hypnotics) medication use, at baseline and 3 years of follow-up, based on therapeutic class codes (See ESM 1 Appendix Methods for details regarding specific medications).

Patterns of psychotropic medication use

Taking non-users of psychotropic medications as a referent category, we defined a variable that combines the dichotomous (“yes” or “no”) variables for antidepressants, anxiolytics, and sedative/hypnotics at WHI enrollment (1993–1998). Specifically, an interaction variable was defined as follows: antidepressant only, anxiolytic only, sedative/hypnotics only, antidepressant + anxiolytic, antidepressant + sedative/hypnotics, anxiolytic + sedative/hypnotics, antidepressant + anxiolytic + sedative/hypnotics. Taking sample size limitations into account, this variable was later categorized as antidepressant only, anxiolytic only, sedative/hypnotic only, and combined psychotropic medication use. For each type of psychotropic medication, we defined patterns of use between enrollment (1993–1998) and 3-year follow-up visits as non-user, user at enrollment only, user at follow-up only, or user at enrollment and follow-up visits (See ESM 1 Appendix Methods for details regarding sample sizes).

Self-reported physical function

The RAND-36 Item Survey was used to assess repeated measures of self-reported physical function at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) and subsequent follow-up visits. It consists of 10 survey questions regarding self-perceived difficulty in specific functional activities [moderate/vigorous activity (2 items); strength to lift, carry, stoop, bend, stair climb (4 items); ability to walk various distances without difficulty (3 items); and self-care (1 item)], each scored as “1=a lot,” “2=a little,” or “3=not at all”, and transformed to generate a total score of 0–100, with higher scores reflecting better function. The RAND-36 was initially administered to WHI-CT participants at enrollment (1993–1998), year 1 and end of follow-up and to WHI-OS participants at enrollment (1993–1998) and year 3 of follow-up, and subsequently at later follow-up times. Continuous RAND-36 scores were dichotomized as < 78 indicating low function or ≥ 78 indicating high function [22, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Change in RAND-36 score over time was also calculated by dividing the difference in RAND-36 score between the last available follow-up and enrollment (1993–1998) visits by the age difference between these two visits. The latest data whereby RAND-36 items were administered using Form 521 became available on February 19, 2022, with durations of follow-up for WHI participants ranging between 7 and 28 years (See ESM 1 Appendix Methods for details regarding sample sizes).

Performance-based physical function

Trained research staff conducted in-person evaluations of grip strength and tested components of the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [balance, timed walk, and chair stand tests] at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS home visit, with mean [±SD] of 16.0 [±1.2] (range: 14–19) years post-WHI enrollment (1993–1998). Accordingly, we defined performance-based physical function at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS home visit using scores that combined these measurements, ranging between 0 and 12, with a score of < 10 indicating worse physical function [22, 48,49,50, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Because SPPB evaluations were not consistently available at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) or earlier follow-up visits among the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS cohort, and because of the long period of time between enrollment (1993–1998) and 2012–2013 WHI-LLS visits, we also examined performance-based physical function over time using data on 5985 WHI-CT participants (≥ 65 years of age at enrollment) for whom specific SPPB evaluations (grip strength, chair stands, gait speed) were performed at WHI enrollment (1993–1998), 1 year, 3 years, and 6 years follow-up visits [47] (See ESM 1 Appendix Methods for details regarding sample sizes).

Covariates

We evaluated several characteristics collected at the WHI enrollment (1993–1998) visit as potential confounders of hypothesized relationships. These characteristics, which are known to be associated with the exposure (psychotropic medications) and outcome (physical function) variables of interest, and are not on the causal pathway between them, include WHI component, socio-demographic characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, education, household income, marital status), lifestyle characteristics (smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity), and health characteristics, namely, body mass index (BMI), comorbid conditions (cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes), symptoms of depression and insomnia, as well as self-rated health. Trained staff collected anthropometric data, including weight [kg] and height [cm] at enrollment [59], and BMI was calculated as (weight (kg) ÷ (height2 (m2)) and further categorized as < 25.0 kg/m2 [underweight/normal weight]; 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 [overweight]; and ≥ 30 kg/m2 [obese]. History of cardiovascular disease was defined in terms of previous coronary heart disease, angina, aortic aneurysm, carotid endarterectomy or angioplasty, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, cardiac arrest, stroke, or transient ischemic attack. History of hypertension was defined as a self-reported diagnosis or treatment for hypertension or evidence of high blood pressure based on systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements. History of diabetes was defined as physician-diagnosed diabetes or use of diabetes medications. History of hyperlipidemia was defined as using lipid-lowering medications or having been told of high cholesterol by a physician. A depressive symptoms screening algorithm previously developed by Burnam et al. with scores ranging between 0 and 1 and higher scores consistent with a greater burden of depressive symptoms was generated using 6 items from the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and 2 items from the National Institute of Mental Health’s Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS). Furthermore, we dichotomized this variable based on a pre-established threshold of 0.06, whereby WHI participants with a score > 0.06 have strong evidence of depressive symptoms while those with a score ≤ 0.06 did not [60,61,62,63,64]. The WHI Insomnia Rating Scale (WHIIRS) consists of five items: whether participants had trouble falling asleep, woke up several times at night, woke up earlier than planned, and had trouble getting back to sleep after awakening early over the past 4 weeks (i.e., response categories coded as follows: 0 = “no, not in the past 4 weeks”; 1 = “yes, less than once per week;” 2 = “yes, 1 to 2 times per week;” 3 = “yes, 3 or 4 times per week;” and 4 = “yes, 5 or more times per week,”) as well as one item on overall sleep quality (coded as: 0 = “very sound or restful,” 1 = “sound or restful,” 2 = “average quality,” 3 = “restless,” and 4 = “very restless.”) These items were summed to calculate an overall insomnia score (range: 0–20). WHIIRS scores > 9 were consistent with diagnostic criteria for insomnia [60, 65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76].

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Summary statistics included mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Bivariate associations were examined using the chi-square test, independent samples t-test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, or their non-parametric counterparts, as appropriate. Linear and logistic regression models were constructed to estimate β coefficients or odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI), before and after controlling for confounders. Linear regression models were applied when the outcome was defined as a continuous variable, whereas logistic regression models were applied when self-reported physical function was defined as < 78 versus ≥ 78 or performance-based physical function was defined as < 10 versus ≥ 10. First, we examined psychotropic (antidepressant, anxiolytic, sedative/hypnotic) medication use in relation to demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and health characteristics at WHI enrollment (1993–1998). Second, we examined self-reported physical function (at enrollment and annualized change between visits) as well as performance-based physical function at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS visit in relation to demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and health characteristics at WHI enrollment (1993–1998). Finally, we examined cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships of psychotropic medication use with physical function scores, before and after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and health characteristics measured at WHI enrollment (1993–1998). Specifically, we constructed fixed-effects and mixed-effects linear and logistic regression models to evaluate antidepressant, anxiolytic, and sedative/hypnotic medication use and their combinations (patterns of use) at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) in relation to (1) self-reported physical function at WHI enrollment (1993–1998), (2) change in self-reported physical function between WHI enrollment (1993–1998) and last available follow-up visits, and (3) performance-based physical function (2012–2013 WHI-LLS visit; WHI-CT random sample: WHI enrollment (1993–1998), 1 year, 3 years, 6 years). For analyses involving the WHI-CT random sample, the GLIMMIX procedure was applied with visit considered a random effect to examine the relationship of psychotropic medication use at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) with performance-based physical function (grip strength, chair stand, gait speed) cross-sectionally and cumulatively over time. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine patterns of psychotropic medication use between WHI enrollment (1993–1998) and 3-year follow-up visits in relation to change in self-reported physical function between WHI enrollment (1993–1998) and the last available follow-up visit. Furthermore, key analyses were repeated after stratifying by levels of depressive and insomnia symptoms. All multivariable models were adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, education, household income, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, BMI, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, symptoms of depression, and insomnia, as well as self-rated health. Complete subject analyses were performed, and two-tailed statistical tests were assessed at an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Study flowchart

Of 7875 2012–2013 WHI-LLS participants, 5262 had no missing data on self-reported or performance-based physical function measurements, and of those, 5125 had no missing data for medication use at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) and 3-year follow-up visits. The final analytic sample consisted of 4557 2012–2013 WHI-LLS (mean [±SD] age at WHI enrollment (1993–1998): 62.79 [±6.95] years) participants, whom, in addition to having complete physical function and medication use data, had no missing demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and health data (Fig. 1a). An additional 5985 WHI-CT participants (≥ 65 years of age at WHI enrollment (1993–1998)) had complete performance-based physical function data available at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) and at 1-, 3-, and 6-year post-enrollment visits (a total of 21,697 observations) (Fig. 1b).

Study flowchart—Women’s Health Initiative Long Life Study and Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trials (age ≥ 65 years) subsamples. Notes: Women’s Health Initiative: The enrollment visit for Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trials and Observational Study occurred between 1993 and 1998. Women’s Health Initiative Long Life Study (Fig. 1A.): The final analytic sample consists of 4557 women who, in 2012–2013, participated in the Women’s Health Initiative Long Life Study, had no missing data on self-reported and performance-based physical function scores, psychotropic medication use at enrollment (1993–1998), and 3-year follow-up, as well as socio-demographic, lifestyle, and health characteristics at enrollment (1993–1998). Self-reported physical function was assessed at enrollment (1993–1998) and the last available follow-up visit, using the RAND-36 scale. The last available follow-up visit for self-reported physical function occurred an average of 22 (± 2.8) (range: 12–27) years after the enrollment (1993–1998) visit. Performance-based physical function was assessed at the 2012–2013 Women’s Health Initiative Long Life Study visit using the Short Physical Performance Battery. Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trials (age ≥ 65 years) (Fig. 1B.): The final analytic sample consists of 5985 Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trials participants (≥ 65 years of age at WHI enrollment) who had performance-based physical function tests (grip strength, chair stand, gait speed) at enrollment (1993–1998), 1-year, 3-year, and 6-year follow-up visits

Psychotropic medications among 2012–2013 WHI-LLS participants

The prevalence rates of antidepressant, anxiolytic, and sedative/hypnotic use at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) visit were 4.2%, 2.2%, and 2.4%, respectively. Antidepressant use differed among ethnic groups, and other variables measured at enrollment (1993–1998) that were directly associated with antidepressant use included lower physical activity scores, smoking, alcohol consumption, as well as history of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. Similarly, the use of anxiolytics was directly associated with history of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes, and use of sedative/hypnotics was directly associated with BMI and history of diabetes measured at enrollment (1993–1998). Also, women with fair/poor self-rated health, high depressive, and/or insomnia symptom scores were more likely to be users of antidepressants, anxiolytic, and/or sedative/hypnotic medications at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) (Table 1).

Physical function among 2012–2013 WHI-LLS participants

Table 2 displays the associations of demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and health characteristics at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) with physical function outcomes, namely, (a) self-reported physical function at enrollment (1993–1998) (mean ± SD: 84.05 ± 17.68, range: 0–100), (b) annualized change in self-reported physical function between the enrollment (1993–1998) visit and the last available follow-up visit (mean ± SD: −1.39 ± 1.44, range: −6.00–4.69), and (c) performance-based physical function at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS follow-up visit (mean ± SD: 8.05 ± 2.69, range: 0–12). The mean (± SD) number of years elapsed between the enrollment (1993–1998) visit and the last available follow-up visit for assessing self-reported physical function was 21.99 (± 2.82), ranging between 12 and 27 years. Disparities in self-reported and performance-based physical function were observed according to most of the selected demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and health characteristics.

Psychotropic medications at enrollment in relation to self-reported physical function among 2012–2013 WHI-LLS participants

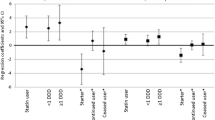

Table 3 presents the results of unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models for psychotropic medications at the 1993–1998 enrollment visit in relation to self-reported physical function at the enrollment (1993–1998) visit and to change in self-reported physical function between the enrollment (1993–1998) visit and the last available follow-up visit, 12 to 27 years later. We observed a negative cross-sectional relationship between antidepressant use and self-reported physical function at enrollment (1993–1998) which remained statistically significant after controlling for confounders (β = −6.27, 95% CI: −8.48, −4.07). Compared to non-users of any psychotropic medications, users of antidepressants alone had a significantly lower self-reported physical function at enrollment (1993–1998) (β = −6.65, 95% CI: −9.02, −4.28), after controlling for confounders. Antidepressant use was cross-sectionally related to lower self-reported physical function [< 78] (OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.48, 2.98) at enrollment (1993–1998). Also, the use of antidepressants alone (versus non-use of psychotropic medications) was cross-sectionally related to lower self-reported physical function [< 78] (OR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.50, 3.18) at enrollment (1993–1998) (ESM 2, Table A.1). Unlike antidepressant medications, anxiolytics and sedative/hypnotics were not cross-sectionally related to self-reported physical function at enrollment (1993–1998). In fully adjusted regression models, combined patterns of psychotropic medication use at enrollment (1993–1998) were not significantly related to annualized change in self-reported physical function between enrollment (1993–1998) and the last available follow-up visits, a mean of 22 years later.

Psychotropic medications between enrollment and 3-year follow-up in relation to self-reported physical function among 2012–2013 WHI-LLS participants

Sensitivity analyses with repeated assessments of psychotropic medications at enrollment (1993–1998) and then again at 3-year follow-up indicated that women who reported sedative/hypnotic use at enrollment (1993–1998) but not at the 3-year follow-up visit experienced a decline in self-reported physical function between enrollment (1993–1998) and the last available follow-up visit (β = −0.36, 95% CI: −0.65, −0.079) in a fully adjusted regression model (ESM 2, Table A.2).

Psychotropic medications in relation to performance-based physical function among 2012–2013 WHI-LLS participants

Table 4 presents unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models for the use of psychotropic medications at enrollment (1993–1998) in relation to performance-based physical function at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS follow-up visit. Unadjusted models suggested a negative relationship between antidepressants taken alone (or in combination with sedative/hypnotics) at enrollment (1993–1998) and performance-based physical function at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS follow-up visit; however, these relationships became statistically non-significant after controlling for confounders. By contrast, in a multivariable logistic regression model, antidepressant use at enrollment (1993–1998) was associated with 50% increased odds of lower (< 10) performance-based physical function at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS visit (OR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.05, 2.21) (ESM 2, Table A.3).

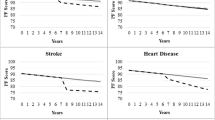

Psychotropic medications in relation to performance-based physical function measures among WHI-CT participants

Table 5 presents mixed-effects linear regression models for use of antidepressant, anxiolytic, and sedative/hypnotic medications at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) in relation to repeated measures (enrollment (1993–1998), 1-year, 3-year, 6-year post-enrollment) of grip strength (17,843 observations), chair stands (16,783 observations), and gait speed (17,762 observations) among a random sample of 21,325 observations linked to 5985 WHI-CT participants, ≥ 65 years of age at enrollment (1993–1998). In fully adjusted models, use of antidepressants was cross-sectionally related to marginally worse performance on grip strength (users vs. non-users: 21.46 (1.92) vs. 21.76 (1.89); P = 0.0071), chair stand (users vs. non-users: 6.48 (0.16) vs. 6.71 (0.12); P < 0.0001), and gait speed (users vs. non-users: 7.06 (0.39) vs. 6.82 (0.30); P = 0.039) tests at enrollment (1993–1998). Use of anxiolytics was cross-sectionally related to marginally worse performance only on the chair stand test (users vs. non-users: 6.54 (0.18) vs. 6.71 (0.12); P = 0.0011) at enrollment (1993–1998). By contrast, hypnotics/sedatives were not cross-sectionally related to performance-based physical function measures at enrollment (1993–1998). Use of psychotropic medications at enrollment (1993–1998) was not associated with a decline in any of the performance-based physical function measures.

Key analyses stratified by depressive and insomnia symptoms

Multiple linear regression models for relationships of psychotropic medication (i.e., antidepressant and sedative/hypnotic) use at enrollment (1993–1998) with key continuous physical function outcomes are displayed after stratifying by levels of depressive (Table A.4.) and insomnia (Table A.5.) symptoms at enrollment (1993–1998). At enrollment (1993–1998), use of hypnotics was cross-sectionally associated with grip strength among women with low (≤ 9) and high (> 9) levels of insomnia symptoms, with a significant interaction effect (Pinteraction = 0.006). Among women with WHIIRS score ≤ 9, grip strength was significantly lower among users (21.72 [0.70]) vs. non-users (22.13 [0.44]) of sedative/hypnotics (P = 0.04), at enrollment (1993–1998). Conversely, among women with WHIIRS score > 9, grip strength was significantly higher among users (22.23 [0.88]) vs. non-users (21.26 [0.68]) of sedative/hypnotics (P = 0.04), at enrollment (1993–1998). There were no other significant interactions between antidepressant use and depressive symptoms or between hypnotic use and insomnia symptoms in relation to the key physical function outcomes.

Discussion

In this epidemiological study, we analyzed data on a sub-sample of > 4000 WHI participants who, in 2012–2013, participated in the WHI-LLS and found that use of anxiolytics was not cross-sectionally or longitudinally associated with self-reported or performance-based physical function, whereas antidepressant use assessed at WHI enrollment (1993–1998) was cross-sectionally (but not longitudinally) related to worse self-reported physical function and was associated with worse performance-based physical function at the 2012–2013 WHI-LLS follow-up visit. Unexpected results of analyses involving this sub-sample of > 4000 WHI participants were that, compared to non-users, those using sedative/hypnotics at enrollment (1993–1998) but not at the 3-year follow-up visit self-reported a decline in physical function over an average of 22 years of follow-up. Mixed models constructed using a subsample of > 5000 WHI-CT participants (≥ 65 years of age at enrollment (1993–1998)) suggested that (a) psychotropic medication use at enrollment (1993–1998) was not longitudinally related to performance-based physical function tests, (b) sedative/hypnotic use at enrollment (1993–1998) was not cross-sectionally related to performance-based physical function tests, but the relationship with grip strength was dependent on level of insomnia symptoms; (c) use of antidepressants or anxiolytics at enrollment (1993–1998) was cross-sectionally, but marginally, related to worse performance on the chair stand test; and, (d) antidepressant use at enrollment (1993–1998) was cross-sectionally, but marginally, related to worse performance on grip strength and gait speed tests.

A thorough review of the literature indicated that evidence linking psychotropic medication use to self-reported and performance-based physical function remains scarce. However, there are numerous studies that have linked physical function to underlying conditions for which the psychotropic medications we studied are often prescribed. It is important to note that, in clinical practice, symptoms and diagnoses may not match with, and therefore, are not acceptable proxies for medication type. Despite having symptoms and/or being diagnosed with a specific condition, individuals may not be treated with the types of psychotropic medications under study. Nevertheless, published studies examining the association of depression and/or anxiety with physical function may provide insight into our broadly defined study question. For instance, a community-based prospective cohort study of individuals, > 65 years of age, suggested that late-life depression may be associated with a greater risk of mortality with physical inactivity and hand-grip strength partly mediating this association [7]. Another cohort study of community-dwelling participants, 80 years and older, found that depression was associated with lower 4-m walking test and SPPB scores and increased number of impaired Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, though not significantly associated with hand-grip strength or Basic Activities of Daily Living scores [8]. Analyses of 5-year longitudinal cohort data on adults, 70–79 years at baseline, from the Health, Aging and Body Composition (Health ABC) study suggested that anxiety symptoms were not associated with declines in objectively measured physical performance but were associated with declines in self-reported functioning over a 5-year follow-up period [77]. An evaluation of baseline psychiatric status in relation to a 6-year trajectory of objective physical function in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety [78] suggested no differences in the rate of decline over time, whereas women with current depression/anxiety had poorer hand-grip strength compared to non-anxious/depressed women during the 6-year follow-up [78]. Finally, mixed growth curve models using annual surveys of community-dwelling adults with chronic conditions suggested significant concurrent and longitudinal associations of anxiety with self-reported physical function, cognitive function, and satisfaction with social roles, independent of depression severity [5]. Whereas both anxiety and depression exhibited similar effect sizes in their unique relationships with each outcome, depression was more strongly associated with satisfaction with social roles and physical function than anxiety [5].

Compared to studies of depression and anxiety, there has been more interest in cross-sectional and longitudinal evaluations of the relationship between sleep parameters and physical function [15, 17,18,19, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders are highly enmeshed with no clear causal relationship among them. Psychotropic medications prescribed for these indications only add to the difficulty in understanding how variations in physical function found in our analyses relate to each of the underlying conditions. Although use of sedative/hypnotics was not cross-sectionally related to physical function in this study, the finding that inconsistent use of sedative/hypnotics may be a risk factor for decline in physical function is unexpected and novel, although it might reflect a propensity for medication adherence or a beneficial effect of sedative/hypnotics on sleep quality, and, consequently, on physical function. Study replication is needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

Previous studies have suggested that psychotropic medications may increase morbidity and mortality risks and have a negative impact on physical function among older adults. For example, An et al. examined the relationship between antidepressant use and onset of functional limitations pertaining to physical mobility, large muscle function, activities of daily living, gross motor function, fine motor function, and instrumental activities of daily living, among Health and Retirement Study participants, showing that antidepressant use for ≥ 12 months was associated with greater risk of functional limitation by 8%, whereas the relationship between use of antidepressants for < 12 months and functional limitation was statistically non-significant [29]. Antidepressant use was associated with a greater risk of functional limitation by 8% among currently non-depressed participants but not currently depressed participants [29], highlighting the complex entanglement of psychotropic medications with underlying conditions and indications. Blazer et al. analyzed sociodemographic and health characteristics in relation to anxiolytic, sedative, and hypnotic medication in a community-based, bi-racial cohort of 4000 older adults followed for 10 years [12]. Overall, 13.3% of subjects were taking these medications at baseline, with the proportion 10 years later only modestly less at 11.8% [12]. Correlates of use at baseline and follow-up were female gender, white race, depression symptoms, poor self-rated health, health services use, and physical disability defined based on items from the modified Katz Activities of Daily Living scale, the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale, and the Rosow-Breslow Physical Health Scale [12]. Finally, Hartz and Ross analyzed data on 148,938 postmenopausal women, aged 50–79 years at baseline, from the WHI to evaluate baseline hypnotic use in relation to risks of mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, and seven types of cancer, over a median follow-up time of 8 years [32], yielding results that are somewhat inconsistent with our study. For women who used hypnotic medications almost daily, the age-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for mortality was 1.62 [32]. Greater hypnotic use was associated with less healthy levels of self-reported physical function, general health, and smoking at baseline [32]. After adjustment for these factors, the HR for almost daily hypnotic use was 1.14 for mortality and 1.53 for melanoma but not significantly associated with increased incidence of other diseases or disorders examined [32]. Less frequent hypnotic use and most types of sleeping difficulties were not associated with mortality, but sleeping more than 10 h a night had a risk-adjusted HR for mortality of 1.28 [32].

A strength of the study is that the WHI study involves detailed data collection at enrollment which facilitates the evaluation of hypothesized relationships taking key confounders into consideration. Second, analyses of WHI data could be generalized to postmenopausal women of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds that reside in various geographical areas within the U.S. However, there are several limitations necessitating cautious interpretation of study findings. First, data from WHI clinical trials and observational studies were combined in these analyses, although they consist of multiple studies that differ in terms of design and eligibility criteria. Second, missing data on exposure, outcome, and covariate variables may have resulted in selection bias. Third, given that most of the variables were assessed through self-report, non-differential misclassification may have resulted in the underestimation of exposure-outcome relationships. Fourth, residual confounding, due to unmeasured or inadequately measured confounders as well as confounding by indication, remains a concern for observational study designs. For instance, the relationship between psychotropic medication use and physical function may be confounded by complex characteristics such as access to and use of healthcare services, which were not adequately evaluated in this study. Although multivariable models controlled for depressive and insomnia symptoms, we were unable to control for anxiety symptoms and could not ascertain the specific indications for the use of psychotropic medications. Thus, disentangling the role of a psychotropic medication from that of its indicated health condition remains an issue to be addressed in future studies. Fifth, it is difficult to ascertain whether a change in the use of psychotropic medications had occurred in the intervening period between baseline and follow-up visits. Accordingly, future studies should incorporate repeated measurements of psychotropic medication use and physical function, which would also elucidate the potential for reverse causality. It is worth noting that a causal relationship between psychotropic medication use and physical function can only be definitively established in the context of an experimental design. Sixth, despite the relatively large sample size, these analyses were adequately powered for evaluating the relationship of antidepressant use with physical function, but likely underpowered to detect marginal differences between users and non-users of other psychotropic medications, especially when less than 5% of the study sample reported using anxiolytics and sedative/hypnotics. A recently published Data Brief by the National Center for Health Statistics estimated the 12-month prevalence rates of any mental health treatment, prescription medication, and counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, at 20.3%, 16.5%, and 10.1%, respectively, in 2020 [79]. Thus, study results may not generalize to contemporaneous populations of postmenopausal women, whereby use of psychotropic medications has become more commonplace in recent years. Finally, the WHI is not population-based but involves volunteers at clinical centers, specifically targeting postmenopausal women. Therefore, its generalizability to men as well as younger and less-educated women is not possible.

In conclusion, the use of antidepressants, not anxiolytics or hypnotics, was cross-sectionally related to worse self-reported physical function and was also associated with worse performance-based physical function > 20 years later, among postmenopausal women. These preliminary findings should be validated using larger samples with repeated measurements of psychotropic medications and physical function to determine the bi-directional relationship between these two constructs. Complex relationships involving hypnotic/sedatives necessitate further investigation. Future studies should explore the use of advanced analytic techniques such as Mendelian randomization or negative controls to address the issue of confounding by indication. Reliance on large claims and electronic health record databases can aid in answering questions pertaining to the cost-effectiveness of psychotropic medication use among different patient subgroups defined according to their disease severity and duration.

Data availability

Data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Obuobi-Donkor G, Nkire N, Agyapong VIO. Prevalence of major depressive disorder and correlates of thoughts of death, suicidal behaviour, and death by suicide in the geriatric population-a general review of literature. Behav Sci (Basel). 2021;11(11):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110142.

Garatachea N, Molinero O, Martinez-Garcia R, Jimenez-Jimenez R, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Marquez S. Feelings of well being in elderly people: relationship to physical activity and physical function. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48(3):306–12.

Vaughan L, Leng X, La Monte MJ, Tindle HA, Cochrane BB, Shumaker SA. Functional independence in late-life: maintaining physical functioning in older adulthood predicts daily life function after age 80. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S79–86.

Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Hill KD, Flicker L. Depression among nonfrail old men is associated with reduced physical function and functional capacity after 9 years follow-up: the health in men cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(1):65–9.

Battalio SL, Glette M, Alschuler KN, Jensen MP. Anxiety, depression, and function in individuals with chronic physical conditions: a longitudinal analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63(4):532–41.

Davis JC, Falck RS, Best JR, Chan P, Doherty S, Liu-Ambrose T. Examining the inter-relations of depression, physical function, and cognition with subjective sleep parameters among stroke survivors: a cross-sectional analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(8):2115–23.

Hamer M, Bates CJ, Mishra GD. Depression, physical function, and risk of mortality: National Diet and Nutrition Survey in adults older than 65 years. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(1):72–8.

Russo A, Cesari M, Onder G, Zamboni V, Barillaro C, Pahor M, Bernabei R, Landi F. Depression and physical function: results from the aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE Study). J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20(3):131–7.

Scopaz KA, Piva SR, Wisniewski S, Fitzgerald GK. Relationships of fear, anxiety, and depression with physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):1866–73.

Stegenga BT, Nazareth I, Torres-Gonzalez F, Xavier M, Svab I, Geerlings MI, Bottomley C, Marston L, King M. Depression, anxiety and physical function: exploring the strength of causality. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(7):e25.

Zhao M, Wang Y, Wang S, Yang Y, Li M, Wang K. Association between depression severity and physical function among Chinese nursing home residents: the mediating role of different types of leisure activities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063543.

Blazer D, Hybels C, Simonsick E, Hanlon JT. Sedative, hypnotic, and antianxiety medication use in an aging cohort over ten years: a racial comparison. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(9):1073–9.

Glaser AP, Mansfield S, Smith AR, Helfand BT, Lai HH, Sarma A, Yang CC, Taddeo M, Clemens JQ, Cameron AP, et al. Impact of sleep disturbance, physical function, depression and anxiety on male lower urinary tract symptoms: results from the symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction research network (LURN). J Urol. 2022;208(1):155–63.

van Milligen BA, Vogelzangs N, Smit JH, Penninx BW. Physical function as predictor for the persistence of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):828–32.

Arias-Fernandez L, Smith-Plaza AM, Barrera-Castillo M, Prado-Suarez J, Lopez-Garcia E, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Lana A. Sleep patterns and physical function in older adults attending primary health care. Fam Pract. 2021;38(2):147–53.

Bhushan B, Beneat A, Ward C, Satinsky A, Miller ML, Balmert LC, Maddalozzo J. Total sleep time and BMI z-score are associated with physical function mobility, peer relationship, and pain interference in children undergoing routine polysomnography: a PROMIS approach. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(4):641–8.

Campanini MZ, Mesas AE, Carnicero-Carreno JA, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E. Duration and quality of sleep and risk of physical function impairment and disability in older adults: results from the ENRICA and ELSA cohorts. Aging Dis. 2019;10(3):557–69.

Fujisawa C, Umegaki H, Nakashima H, Kuzuya M, Toba K, Sakurai T. Complaint of poor night sleep is correlated with physical function impairment in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(2):171–2.

Huang WC, Lin CY, Togo F, Lai TF, Liao Y, Park JH, Hsueh MC, Park H. Association between objectively measured sleep duration and physical function in community-dwelling older adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):515–20.

Kakizaki M, Kuriyama S, Nakaya N, Sone T, Nagai M, Sugawara Y, Hozawa A, Fukudo S, Tsuji I. Long sleep duration and cause-specific mortality according to physical function and self-rated health: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(2):209–16.

Kim M, Yoshida H, Sasai H, Kojima N, Kim H. Association between objectively measured sleep quality and physical function among community-dwelling oldest old Japanese: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(8):1040–8.

Kline CE, Colvin AB, Pettee Gabriel K, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Cauley JA, Hall MH, Matthews KA, Ruppert KM, Neal-Perry GS, Strotmeyer ES, et al. Associations between longitudinal trajectories of insomnia symptoms and sleep duration with objective physical function in postmenopausal women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Sleep. 2021;44(8):zsab059. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab059.

Lorenz RA, Budhathoki CB, Kalra GK, Richards KC. The relationship between sleep and physical function in community-dwelling adults: a pilot study. Fam Community Health. 2014;37(4):298–306.

Okoye SM, Szanton SL, Perrin NA, Nkimbeng M, Schrack JA, Han HR, Nyhuis C, Wanigatunga S, Spira AP. Objectively measured sleep and physical function: associations in low-income older adults with disabilities. Sleep Health. 2021;7(6):735–41.

Song Y, Dzierzewski JM, Fung CH, Rodriguez JC, Jouldjian S, Mitchell MN, Josephson KR, Alessi CA, Martin JL. Association between sleep and physical function in older veterans in an adult day healthcare program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(8):1622–7.

Stenholm S, Kronholm E, Bandinelli S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Self-reported sleep duration and time in bed as predictors of physical function decline: results from the InCHIANTI study. Sleep. 2011;34(11):1583–93.

Thorpe RJ Jr, Gamaldo AA, Salas RE, Gamaldo CE, Whitfield KE. Relationship between physical function and sleep quality in African Americans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(10):1323–9.

Kvelde T, Lord SR, Close JC, Reppermund S, Kochan NA, Sachdev P, Brodaty H, Delbaere K. Depressive symptoms increase fall risk in older people, independent of antidepressant use, and reduced executive and physical functioning. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(1):190–5.

An R, Lu L. Antidepressant use and functional limitations in U.S. older adults. J Psychosom Res. 2016;80:31–6.

Hafferty JD, Wigmore EM, Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Campbell AI, MacIntyre DJ, Nicodemus KK, Lawrie SM, Porteous DJ, et al. Pharmaco-epidemiology of antidepressant exposure in a UK cohort record-linkage study. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(4):482–93.

Kramer M. Hypnotic medication in the treatment of chronic insomnia: non nocere! Doesn’t anyone care? Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(6):529–41.

Hartz A, Ross JJ. Cohort study of the association of hypnotic use with mortality in postmenopausal women. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e001413. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001413.

Frisard C, Gu X, Whitcomb B, Ma Y, Pekow P, Zorn M, Sepavich D, Balasubramanian R. Marginal structural models for the estimation of the risk of diabetes mellitus in the presence of elevated depressive symptoms and antidepressant medication use in the Women’s Health Initiative observational and clinical trial cohorts. BMC Endocr Disord. 2015;15:56.

Goveas JS, Hogan PE, Kotchen JM, Smoller JW, Denburg NL, Manson JE, Tummala A, Mysiw WJ, Ockene JK, Woods NF, et al. Depressive symptoms, antidepressant use, and future cognitive health in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(8):1252–64.

Kiridly-Calderbank JF, Sturgeon SR, Kroenke CH, Reeves KW. Antidepressant use and risk of colorectal cancer in the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(8):892–8.

Lakey SL, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, Borson S, Williams CD, Calhoun D, Goveas JS, Smoller JW, Ockene JK, Masaki KH, et al. Antidepressant use, depressive symptoms, and incident frailty in women aged 65 and older from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):854–61.

Smoller JW, Allison M, Cochrane BB, Curb JD, Perlis RH, Robinson JG, Rosal MC, Wenger NK, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Antidepressant use and risk of incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2128–39.

Beydoun HA, Saquib N, Wallace RB, Chen JC, Coday M, Naughton MJ, Beydoun MA, Shadyab AH, Zonderman AB, Brunner RL. Psychotropic medication use and Parkinson’s disease risk amongst older women. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9(8):1163–76.

Haines A, Shadyab AH, Saquib N, Kamensky V, Stone K, Wassertheil-Smoller S. The association of hypnotics with incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in older women with sleep disturbances. Sleep Med. 2021;83:304–10.

Leaney AA, Lyttle JR, Segan J, Urquhart DM, Cicuttini FM, Chou L, Wluka AE. Antidepressants for hip and knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;10:CD012157.

Mathur S, Roberts-Toler C, Tassiopoulos K, Goodkin K, McLaughlin M, Bares S, Koletar SL, Erlandson KM, Team AAS. Detrimental effects of psychotropic medications differ by sex in aging people with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(1):88–95.

Anderson GL, Manson J, Wallace R, Lund B, Hall D, Davis S, Shumaker S, Wang CY, Stein E, Prentice RL. Implementation of the Women’s Health Initiative study design. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S5–17.

Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Limacher M, Allen C, Rossouw JE. The Women’s Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S18–77.

Beasley JM, Rillamas-Sun E, Tinker LF, Wylie-Rosett J, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Datta M, Caan BJ, LaCroix AZ. Dietary intakes of Women’s Health initiative long life study participants falls short of the dietary reference intakes. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(9):1530–7.

Haring B, McGinn AP, Kamensky V, Allison M, Stefanick ML, Schnatz PF, Kuller LH, Berger JS, Johnson KC, Saquib N, et al. Low diastolic blood pressure and mortality in older women. Results from the Women’s Health Initiative Long Life Study. Am J Hypertens. 2022;35(9):795–802.

Luo J, Thomson CA, Hendryx M, Tinker LF, Manson JE, Li Y, Nelson DA, Vitolins MZ, Seguin RA, Eaton CB, et al. Accuracy of self-reported weight in the Women’s Health Initiative. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(6):1019–28.

Laddu DR, Wertheim BC, Garcia DO, Brunner R, Groessl E, Shadyab AH, Going SB, LaMonte MJ, Cannell B, LeBoff MS, et al. Associations between self-reported physical activity and physical performance measures over time in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(10):2176–81.

Atkinson HH, Rapp SR, Williamson JD, Lovato J, Absher JR, Gass M, Henderson VW, Johnson KC, Kostis JB, Sink KM, et al. The relationship between cognitive function and physical performance in older women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative memory study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(3):300–6.

Bea JW, Going SB, Wertheim BC, Bassford TL, LaCroix AZ, Wright NC, Nicholas JS, Heymsfield SB, Chen Z. Body composition and physical function in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:15–22.

Beasley JM, Wertheim BC, LaCroix AZ, Prentice RL, Neuhouser ML, Tinker LF, Kritchevsky S, Shikany JM, Eaton C, Chen Z, et al. Biomarker-calibrated protein intake and physical function in the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1863–71.

Brunner RL, Cochrane B, Jackson RD, Larson J, Lewis C, Limacher M, Rosal M, Shumaker S, Wallace R. Women’s Health Initiative I: Calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and physical function in the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(9):1472–9.

Michael YL, Gold R, Manson JE, Keast EM, Cochrane BB, Woods NF, Brzyski RG, McNeeley SG, Wallace RB. Hormone therapy and physical function change among older women in the Women’s Health Initiative: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2010;17(2):295–302.

Michael YL, Wu C, Pan K, Seguin-Fowler RA, Garcia DO, Zaslavsky O, Chlebowski RT. Postmenopausal breast cancer and physical function change: a difference-in-differences analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):1029–36.

Patel KV, Cochrane BB, Turk DC, Bastian LA, Haskell SG, Woods NF, Zaslavsky O, Wallace RB, Kerns RD. Association of pain with physical function, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and sleep quality among veteran and non-veteran postmenopausal women. Gerontologist. 2016;56 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S91–101.

Rillamas-Sun E, LaCroix AZ, Bell CL, Ryckman K, Ockene JK, Wallace RB. The impact of multimorbidity and coronary disease comorbidity on physical function in women aged 80 years and older: the Women’s Health Initiative. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S54–61.

Rosso AL, Lee BK, Stefanick ML, Kroenke CH, Coker LH, Woods NF, Michael YL. Caregiving frequency and physical function: the Women’s Health Initiative. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(2):210–5.

Seguin R, Lamonte M, Tinker L, Liu J, Woods N, Michael YL, Bushnell C, Lacroix AZ. Sedentary behavior and physical function decline in older women: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:271589.

Zhu K, Wactawski-Wende J, Ochs-Balcom HM, LaMonte MJ, Hovey KM, Evans W, Shankaran M, Troen BR, Banack HR. The Association of muscle mass measured by D3-creatine dilution method with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and physical function in postmenopausal women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(9):1591–9.

Jung SY, Ho G, Rohan T, Strickler H, Bea J, Papp J, Sobel E, Zhang ZF, Crandall C. Interaction of insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin resistance-related genetic variants with lifestyle factors on postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(2):475–95.

Kling JM, Manson JE, Naughton MJ, Temkit M, Sullivan SD, Gower EW, Hale L, Weitlauf JC, Nowakowski S, Crandall CJ. Association of sleep disturbance and sexual function in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2017;24(6):604–12.

Patel KV, Cochrane BB, Turk DC, Bastian LA, Haskell SG, Woods NF, Zaslavsky O, Wallace RB, Kerns RD. Association of pain with physical function, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and sleep quality among veteran and non-veteran postmenopausal women. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S91–101.

Sands M, Loucks EB, Lu B, Carskadon MA, Sharkey K, Stefanick M, Ockene J, Shah N, Hairston KG, Robinson J, et al. Self-reported snoring and risk of cardiovascular disease among postmenopausal women (from the Women’s Health Initiative). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(4):540–6.

Zaslavsky O, LaCroix AZ, Hale L, Tindle H, Shochat T. Longitudinal changes in insomnia status and incidence of physical, emotional, or mixed impairment in postmenopausal women participating in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study. Sleep Med. 2015;16(3):364–71.

Danhauer SC, Brenes GA, Levine BJ, Young L, Tindle HA, Addington EL, Wallace RB, Naughton MJ, Garcia L, Safford M, et al. Variability in sleep disturbance, physical activity and quality of life by level of depressive symptoms in women with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2019;36(9):1149–57.

Cauley JA, Hovey KM, Stone KL, Andrews CA, Barbour KE, Hale L, Jackson RD, Johnson KC, LeBlanc ES, Li W, et al. Characteristics of self-reported sleep and the risk of falls and fractures: the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). J Bone Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2019;34(3):464–74.

Creasy SA, Crane TE, Garcia DO, Thomson CA, Kohler LN, Wertheim BC, Baker LD, Coday M, Hale L, Womack CR, et al. Higher amounts of sedentary time are associated with short sleep duration and poor sleep quality in postmenopausal women. Sleep. 2019;42(7):zsz093. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz093.

Chen JC, Espeland MA, Brunner RL, Lovato LC, Wallace RB, Leng X, Phillips LS, Robinson JG, Kotchen JM, Johnson KC, et al. Sleep duration, cognitive decline, and dementia risk in older women. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(1):21–33.

Generaal E, Vogelzangs N, Penninx BW, Dekker J. Insomnia, sleep duration, depressive symptoms, and the onset of chronic multisite musculoskeletal pain. Sleep. 2017;40(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw030.

Grieshober L, Wactawski-Wende J, Hageman Blair R, Mu L, Liu J, Nie J, Carty CL, Hale L, Kroenke CH, LaCroix AZ, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of telomere length and sleep in the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(9):1616–26.

Beverly Hery CM, Hale L, Naughton MJ. Contributions of the Women’s Health Initiative to understanding associations between sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep-disordered breathing across a range of health outcomes in postmenopausal women. Sleep Health. 2020;6(1):48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2019.09.005.

Ochs-Balcom HM, Hovey KM, Andrews C, Cauley JA, Hale L, Li W, Bea JW, Sarto GE, Stefanick ML, Stone KL, et al. Short sleep is associated with low bone mineral density and osteoporosis in the Women’s Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(2):261–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3879.

Royse KE, El-Serag HB, Chen L, White DL, Hale L, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Jiao L. Sleep duration and risk of liver cancer in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative study. J Women's Health. 2017;26(12):1270–7.

Rissling MB, Gray KE, Ulmer CS, Martin JL, Zaslavsky O, Gray SL, Hale L, Zeitzer JM, Naughton M, Woods NF, et al. Sleep disturbance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal veteran women. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S54–66.

Soucise A, Vaughn C, Thompson CL, Millen AE, Freudenheim JL, Wactawski-Wende J, Phipps AI, Hale L, Qi L, Ochs-Balcom HM. Sleep quality, duration, and breast cancer aggressiveness. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(1):169–78.

Levine DW, Kaplan RM, Kripke DF, Bowen DJ, Naughton MJ, Shumaker SA. Factor structure and measurement invariance of the Women’s Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess. 2003;15(2):123–36.

Levine DW, Kripke DF, Kaplan RM, Lewis MA, Naughton MJ, Bowen DJ, Shumaker SA. Reliability and validity of the Women's Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess. 2003;15(2):137–48.

Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Brenes GA, Newman AB, Shorr RI, Simonsick EM, Ayonayon HN, Rubin SM, Covinsky KE. Anxiety symptoms and decline in physical function over 5 years in the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):265–70.

Lever-van Milligen BA, Lamers F, Smit JH, Penninx BW. Six-year trajectory of objective physical function in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(2):188–97.

Terlizzi EP, Norris T. Mental health treatment among adults: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;419:1–8.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore, Maryland. The authors thank the WHI investigators and staff for their dedication and the study participants for making the program possible. A listing of WHI investigators can be found at https://www-whi-org.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/WHI-Investigator-Short-List.pdf. The sponsors did not play a role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through 75N92021D00001, 75N92021D00002, 75N92021D00003, 75N92021D00004, and 75N92021D00005. This analysis did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the A.T. Augusta Military Medical Center, the Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Any discussion or mention of commercial products or brand names does not imply or support any endorsement by the Federal Government.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary file 1

(DOCX 52 kb)

Supplementary file 2

(DOCX 35 kb)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Beydoun, H.A., Beydoun, M.A., Kwon, E. et al. Relationship of psychotropic medication use with physical function among postmenopausal women. GeroScience (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01141-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01141-z