Abstract

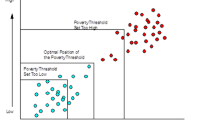

Determining the threshold separating poor from non-poor populations is one of the most influential choices when measuring poverty. Commonly used selection criteria leave considerable room for discretion or are not appropriate as academic standards. This vacuum in academic guidance leads to arbitrary and/or ideologically driven choices. This can greatly influence the measurement of a societal phenomenon, and thus research and public policy decisions over a period that extends well beyond the mandate of those making that threshold decision. This paper sets out an empirical validation method that contributes to reducing the range of thresholds and thereby aids decision-makers in making that normative decision. Our method uses an absolute concept of empirical validity and requires that the microdata for measuring poverty hold additional information closely associated with poverty. The method builds on insights from theory on measurement error that, for any given threshold, some persons are wrongly identified as poor (false positives) and others are wrongly identified as not poor (false negatives), and that the reduction of one error can only be attained by increasing the other. Our method uses the additional microdata to disaggregate the population into (likely) false positives and (likely) false negatives and analyzes marginal changes in this composition as the poverty threshold becomes stricter. Using Canadian data, we show that this approach substantially narrows the range of thresholds for two unidimensional poverty indicators, namely a material deprivation and an income poverty indicator. The underlying principle of the method extends to other (unidimensional) social indicators. The analysis itself can also serve other purposes, such as deepening our understanding of poverty and the cost-effectiveness of policies to reduce it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The dimensionality of an indicator reflects a continuum and this paper focuses on poverty indicators situated (more) on the unidimensional side, leaving the question on whether the approach developed here would also be useful for multidimensional indicators for future research.

This paper uses the term “likelihood of poverty” colloquially, thus conferring the meaning “the chances that” rather than its narrower and probabilistic meaning in statistics jargon.

We use the wording ‘strictness’ in this definition because an increase in strictness may reflect either an increase or a decrease in the numerical value depending on the poverty indicator used. For instance, a stricter material deprivation threshold implies a higher numerical value (e.g., from one to two deprivations) whereas a stricter income poverty threshold implies a lower numerical value (e.g., from two to one currency units). Furthermore, depending on the poverty indicator, the scale can be ordinal or cardinal.

The income threshold values (in Canadian Dollars) are $14,325 (30 percent), $19,100 (40 percent), $23,875 (50 percent), $28,650 (60 percent) and $33,425 (70 percent).

The income poverty rate at the 50 percent of median threshold in this paper differs from the official LIM rates published by Statistics Canada (see Table https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110013501, accessed 23 May 2018). This is because income in the CSEW data is self-reported while the official income poverty data are calculated largely using tax files. This is also because we calculate the before-tax LIM rate as the data do not have the preferable after-tax information whereas the CANSIM tables list the after-tax LIM rate. Unpublished calculations with the data source used for official poverty statistics give a before-tax LIM rate of 17.6 percent compared to 15.9 percent in our paper.

This lack of overlap between the two indicators of material poverty is well documented in the literature and has given rise to a broad consensus that income and material deprivation indicators are complements rather than substitutes (e.g., Cancian and Meyer, 2004; Fusco et al., 2011; Nolan and Whelan, 2011). This paper focuses on how to set a poverty threshold of a unidimensional indicator, and thus leaves aside considerations on what set of indicators to use in monitoring progress on poverty and/or the relevance of a multidimensional indicator of poverty.

We apply this argument in the spirit of Sen’s (2001) capability theory; it thus only applies to cases in which a person has the freedom of choice between adequate and realistically feasible alternatives.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that in classifying group B as “high” we give an income below the poverty threshold more weight than the absence of experiencing economic hardship. Group B is very small; categorizing group B as “low” or, alternatively, not counting the group towards any of the two measurement error groups would not change the threshold range for the material deprivation indicator (see Table S3, supplementary appendix).

Table S3 in the supplementary appendix shows the evolution of the composition of each of the six profiles in the materially deprived population at each threshold.

Tables S5 to S10 and accompanying descriptions in the supplementary appendix explain these robustness checks in further detail. A Monte Carlo Simulation, which consisted of performing the empirical validation exercise using 1,000 replicate samples drawn from our dataset, indicates that the chance of identifying an optimal threshold of two using the definitions outlined in step two is 91% (Table S12).

Because our data hold only before-tax total income the income distribution reflects government income transfers received but not income taxes paid. Since we use a relative threshold, we define the threshold range as percentages of the median. For absolute or hybrid thresholds, the range of threshold could be set differently.

A strict equality of weights for the error groups would identify the 40 percent of the median as optimal.

References

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 476–487.

Alkire, S., Foster, J. E., Seth, S., Santos, M. E., Roche, J., & Ballon, P. (2015). Multidimensional Poverty Measurement and Analysis: Chapter 3–Overview of Methods for Multidimensional Poverty Assessment.

Alkire, S., and Santos, M. E. (2009). ‘Poverty and Inequality Measurement’. in An introduction to the human development and capability approach: Freedom and agency. IDRC.

Alkire, S., and Santos, M. E. (2010). Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. United Nations Development Programme Human Development Report Office Background Paper (2010/11).

Atkinson, A. (2003). Multidimensional deprivation: Contrasting social welfare and counting approaches. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 51–65.

Atkinson, A., Cantillon, B., Marlier, E., and Nolan, B. (2002). Social Indicators: The EU and Social Inclusion. OUP Oxford.

Banerjee, A., Chitnis, U. B., Jadhav, S. L., Bhawalkar, J. S., & Chaudhury, S. (2009). Hypothesis testing, type I and type II errors. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 18(2), 127.

Beduk, S. (2018). Missing the unhealthy? Examining empirical validity of material deprivation indices (MDIs) using a partial criterion variable. Social Indicators Research, 135(1), 91–115.

Brodersen, J., Schwartz, L. M., Heneghan, C., O’Sullivan, J. W., Aronson, J. K., and Woloshin, S. (2018). Overdiagnosis: What It Is and What It Isn’t. Royal Society of Medicine.

Cancian, M., & Meyer, D. R. (2004). Alternative measures of economic success among TANF participants: Avoiding poverty, hardship, and dependence on public assistance. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(3), 531–548.

Coady, D., Grosh, M., and Hoddinott, J. (2004). Targeting of transfers in developing countries: Review of lessons and experience. The World Bank.

Colquhoun, D. (2017). The reproducibility of research and the misinterpretation of p-values. Royal Society Open Science, 4(12), 171085.

Davidson, R., & Duclos, J.-Y. (2000). Statistical inference for stochastic dominance and for the measurement of poverty and inequality. Econometrica, 68(6), 1435–1464.

Fisher, G. M. (1992). The development and history of the poverty thresholds. Social Security Bulletin, 55, 3.

Fusco, Alessio, Anne-Catherine Guio, and Eric Marlier. 2011. “Income Poverty and Material Deprivation in European Countries.” LISER.

Gordon, David. 2006. ‘The Concept and Measurement of Poverty’. Poverty and Social Exclusion in Britain. The Millennium Survey, Policy Press, Bristol 29–69.

Guio, A.-C. (2009). What Can be learned from deprivation indicators in Europe. Indicator Subgroup of the Social Protection Committee 10.

Guio, A.-C., Gordon, D., & Marlier, E. (2012). Measuring Material Deprivation in the EU: Indicators for the Whole Population and Child-Specific Indicators. Publications Office of the European Union.

Guio, A.-C., Marlier, E., Gordon, D., Fahmy, E., Nandy, S., & Pomati, M. (2016). Improving the measurement of material deprivation at the European union level. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(3), 219–333.

Liser. (2017). Material and social deprivation: The EU endorses a new indicator developed by LISER’. Retrieved 23 May 2018 (https://www.liser.lu/?type=news&id=1426).

Nandy, S., & Pomati, M. (2015). Applying the consensual method of estimating poverty in a low income African setting. Social Indicators Research, 124(3), 693–726.

National Research Council. (1995). Measuring Poverty: A New Approach. National Academies Press.

Nolan, B., and Whelan, C. T. (2011). Poverty and Deprivation in Europe. OUP Catalogue.

Notten, G., and Kaplan, J. (2021). Material Deprivation: Measuring Poverty by Counting Necessities Households Cannot Afford. Canadian Public Policy 1–17.

Notten, G., Charest, J. and Heisz, A. (2017). Material Deprivation in Canada. University of Ottawa Department of Economics.

Notten, G. (2015). Child poverty in Ontario: The value added of material deprivation indicators for comparative policy analysis in North America. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(5), 533–551.

Notten, G., & De Neubourg, C. (2011). Monitoring absolute and relative poverty:“Not Enough” is not the same as “Much Less.” Review of Income and Wealth, 57(2), 247–269.

Notten, G., & Roelen, K. (2012). A new tool for monitoring (Child) poverty: Measures of cumulative deprivation. Child Indicators Research, 5(2), 335–355.

Saunders, P., & Naidoo, Y. (2009). Poverty, deprivation and consistent poverty. Economic Record, 85(271), 417–432.

Sen, A. (1976). Poverty: An ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 219–31.

Sen, A. (2001). Development as Freedom. Oxford Paperbacks.

Smeeding, T. (2006). Poor people in rich nations: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 69–90.

Statistical hypotheses, verification of. Encyclopedia of Mathematics. http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Statistical_hypotheses,_verification_of&oldid=49601

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. Univ of California Press.

United States Census Bureau. (2018). n.d. The Supplemental Poverty Measure. Retrieved 23 May (https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/demo/p60-261.html).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andrew Heisz and all anonymous reviewers. Their comments helped us to further generalize the method beyond the data on which we first conceived it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Notten, G., Kaplan, J. An Empirical Validation Method for Narrowing the Range of Poverty Thresholds. Soc Indic Res 161, 251–271 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02817-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02817-1