Abstract

Many studies carried out on the evolution of the standard of living have shown that it is advisable to use several indicators as there is no single indicator that reflects all of the dimensions of well-being or that does so without incurring value judgements. Following this line of research, this study examines the well-being of the workers of Alcoy during the industrialisation process using four indicators: real wages, nutrition, life expectancy and height. As happened in other European industrialized regions some decades before, between 1870 and the end of the nineteenth century we can observe a “puzzle” as two indicators point to an increase in the standard of living and the other two reveal the opposite. The “puzzle” later disappears because from the beginning of the twentieth century to 1930 the four indicators show that well-being increased.

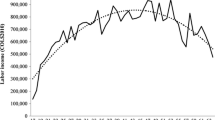

Source: The nominal wages have been obtained from the documentation in the following four archives: the Archivo Municipal de Alcoy, the Archivo de la Diputación Provincial de Alicante, the Archivo de la Real Fábrica de Paños de Alcoy (ARFPA) and the Archivo Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Estadística. The total number of observations was 12,300 wages which provides the sample with sufficient significance. Until 1881, data come from the records of ARFPA, the Hospital´s account books and budget settlements of the City Hall, completed with the occasional available statistics and historical press. Between 1881 and 1930 data come mainly from “Census Books of personal identification cards” and from labor agreements that were signed in the city since 1881

Source: The mercurial books have been consulted in the Archivo Municipal de Alcoy, in the Archivo de la Diputación de Alicante and in the Archivo Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Estadística. The accounts books of the hospital and the housing rental records can be found in the Archivo Municipal de Alcoy. In total, we have obtained 36,000 references of goods and services. See text

Source: Puche Gil (2009). From his excellent work on Alcoy (including 16.102 data of recruits between 19 and 21 years measured from 1876 to 1936) we have selected only the series of conscripts born in the city, and all the data are standardised at age 21

Sources: Budgets of the local government of Alcoy from 1865 to 1911 (sanitary reform) and «Estadística de movimiento natural de la población entre 1843 y 1860» (Archivo Municipal de Alcoy), Register of deaths in Alcoy (Civil register of Alcoy) and Beneito (2003)

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

01 December 2017

In the original publication of this article, Section 5 was missed out and Conclusions part was published incorrectly. Now Section 5 is included, and correct Conclusions section has been provided in this erratum.

Notes

We are referring to Norhdaus and Tobin (1973), Myrdal (1974), Samuelson (1983), or Morris (1979), who proposed alternative well-being indicators to income per person. The Nordhaus and Tobin’s EWM (Economic Well-being Measure) and the Samuelson’s NEW (Net Economic Well-being) modified the income adding variables like the value of leisure time and the housewives’ work and deducting the military costs and the contamination and urban life costs. Morris proposed The Physical Quality of Life Index, which includes life expectancy at the age of 1 year, infant mortality and the adult literacy rate and is obtained through the arithmetic mean of its three parts. Morris has defended the viability of the indicator because it contains a function of well-being defined by the enjoyment of a long life with the possibility of prospering due to literacy and because, in under-developed countries, a substantial part of basic consumption is not made through the market, so infant mortality and life expectancy are better indicators than income for capturing nutrition and health. These variables are also easy to estimate and therefore are more reliable than the dubious figures for income of many under-developed countries.

On the HDI, consult the Human Development Reports published from the year 2000 by the United Nations Development Programme. In 2010, the way to estimate the HDI was modified. The life expectancy was conserved as an indicator of health but the way to estimate education and the income changed, replacing the arithmetic average of the three components by a geometric one.

There is an abundant bibliography on anthropometry. Here we will only mention a few pioneering studies: Fogel and Engerman (1974), Engerman (1976), Eveleth and Tanner (1976), Fogel et al. (1982), Fogel (1989), Tanner (1990), Steckel (1995), Steckel and Floud (1997), Komlos and Baten (1998) and the recent compilation of studies edited by Floud et al. (2014). For Spain, see Martínez-Carrión and Puche (2011).

Pioneer studies which defend the use of several indicators of well-being include Crafts (1997), Floud and Harris (1997) and Horlings and Smits (1998). More recently, Stiglitz et al. (2010). For the Spanish case, Escudero and Simón (2003) have studied the evolution of well-being between 1850 and 1992 using income per person, the Physical Quality of Life Index, the Human Development Index and height.

The war of succession to the Spanish Crown was originated after the death of Carlos II in 1701. France and the Kingdom of Castile defended Felipe of Anjou, of the dynasty of the Bourbons. The Kingdom of Aragon and the Great Coalition (England, United provinces, Austria and Prussia) defended the Archduke Charles, of the dynasty of the Habsburgs. Once Philip of Anjou was named King of Spain, signed the Nueva Planta Decrees, which abolished the ancient privileges of the Crown of Aragon in 1707.

Since we do not have data the Spanish production of wool in the nineteenth century, specialists have used tax data for the main production centres. Data suggest that in 1856, 30% of Spanish wool production came from Terrassa and Sabadell, and 10% of Alcoy. Nadal (2003, p. 141).

Gutiérrez (2011, op. cit.).

In 1860, 60% of the active population worked in the industry and this percentage came to exceed 75% in the Decade of 1920. The data have been calculated by José Joaquín García making use of the municipal censuses of population and the municipal statistics of labourers.

Engel stated that the percentage of income allocated for food purchases decreases as income rises. Economists have extended this definition considering that as a household's income increases, the percentage of income spent on inferior goods decreases while the proportion spent on other goods (such as luxury goods) increases. One of the issues discussed in the debate on the standard of living of the British working class during the Industrial Revolution relates to the conditions that the estimate of real wages should fulfil. See, for example, Flinn (1974), Lindert and Williamson (1983), Crafts (1985), Scholliers (1989), Feinstein (1998) and Clark (2001).

The CPI measures the changes in the price of a market basket of consumer goods and services representing the consumption of the households.

Cost-of living indices of the Spanish regions are those of Moreno Lázaro (2006) for Castilla la Vieja; Lana Berasaín (2005) for Navarre; Molina de Dios (2003) for Mallorca and Pérez Castroviejo (2006) for Biscay. CPIs for the Great Britain of the Industrial Revolution in Feinstein (1998) and Clark (2001).

The apparent consumption is a method widely used in Economy and Economic History to estimate the consumption of a country or a region. It is defined as the production plus imports minus exports, sometimes also adjusted for changes in inventories.

We use the term “nutrition transition” in the sense proposed by Popkin (1993). An initial period before the Neolithic period which Popkin called “food collection” was followed by the “hunger” stage. At the end of the eighteenth century, another phase began characterised by diets based on saturated fats, sugar and carbohydrates which, well into the twentieth century gave rise to an increase in obesity. We should point out that the nutrition transition did not occur in the same way in Atlantic Europe as it did in Mediterranean Europe as in the latter case it began later and was a slower process. See Pujol and Cussó (2014).

This can be clearly seen between the end of the 1860s and the 1890s when the population of Alcoy increased by 30%.

On the urban penalty, Preston and Van de Walle (1978), Woods and Woodward (1984), Woodward (1984), Kearns (1988, 1991), Bairoch (1988), Schofield et al. (1991), Mooney (1994), Vögele (1998, 2000), Szreter and Mooney (1998), Woods (2000, 2003), Haines (2001, 2004). A statement of the situation in Spanish is to be found in Escudero and Nicolau (2014).

The construction of housing requires a series of previous conditions which extend the execution time of the works (the project design, purchase of the land, construction license, bank loans, hiring of the construction company and the time of execution was rarely less than 2 years). Although there are many studies that explain why adjustments in the real estate markets do not take place in the short term, we can highlight Smith et al. (1988).

Other measures proposed by the hygienists were the paving of the streets, refuse collection, vaccination, the “Gotas de Leche” child nutrition programme and the outreach campaigns about child care and child nutrition and personal and domestic hygiene. On health reform in the cities, see Szreter (2002a, b, c, 2005). Also Bell and Millward (1998), Fraser (1993), Luckin (2000), Harris (2004) and Sheard and Power (2000).

In fact, in other Spanish city suffering urban penalty as La Unión, this percentage reached to 86.4% between 1877 and 1900. (Escudero, García-Gómez and Martínez Soto, work in reviewing).

For child labour and the harsh working conditions in Alcoy during the industrialisation process, see Beneito (2003).

A more in-depth analysis of the evolution of nominal and real wages can be found in García-Gómez (2013), pp. 503–536.

The period known in Spain as the Restoration began in 1876 when a military coup d’état restored the monarchy under Alfonso XIII and ended in 1923 when General Primo de Rivera established the Dictatorship.

The settlements can be found in the Archivo Municipal de Alcoy.

From the beginning of the twentieth century, the State enacted legislation that improved working conditions: regulation of child and female labour, a reduction in the working day to 9 h and the Sunday rest law. See Beneito (2003).

References

Aracil, R., & García, M. (1974). Industrialització al País Valencià: el cas d´Alcoi. Valencia: Eliseu Climent.

Bairoch, P. (1988). Cities and economic development. From the dawn of history to the present. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bell, F., & Millward, R. (1998). Public health expenditures and mortality in England and Wales, 1870–1914. Continuity and Change, 13, 221–249.

Beneito, À. (1993). Comportamiento epidémico y evolución de las causas de defunción en la comarca de l´Alcoià-El Comtat. Siglos XIX–XX. Alicante: Unpublished Doctoral thesis.

Beneito, À. (2003). Condicions de vida i salut a Alcoi durant el procés d’industrialització. Valencia: Universitat Politècnica de València.

Cerdá, E. (1967). Monografía sobre la industria papelera. Gráficas Aitana: Alcoy.

Cerdá, E. (1980). Lucha de clases e industrialización. Valencia: Ed. Almudín.

Clark, G. (2001). Farm wages and living standards in the industrial revolution: England, 1670–1869. Economic History Review, 54, 477–505.

Crafts, N. F. R. (1985). English workers’ real wages during the industrial revolution: Some remaining problems. Journal of Economic History, 45, 139–144.

Crafts, N. F. R. (1997). Some dimensions of the quality of life during the British industrial revolution. Economic History Review, 50(4), 617–639.

Cuevas, J. (1999). Los orígenes financieros de la industria de Alcoi (1770–1900). Alicante: Unpublished Doctoral thesis.

Dávila, J. M. (1993). Alcoy: desarrollo urbano y planeamiento. Alicante: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante.

Deaton, A. (2013). The great escape: Health, wealth, and the origins of inequality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Engerman, S. (1976). The Height of U.S. Slaves. Local Population Studies, 16, 45–50.

Escudero, A., & Nicolau, R. (2014). Urban penalty: nuevas hipótesis y caso español (1860–1923). Historia Social, 80, 9–23.

Escudero, A., & Simón, H. (2003). El bienestar en España: una perspectiva de largo plazo (1850–1992). Revista de Historia Económica, 3, 525–565.

Eveleth, P. B., & Tanner, J. M. (1976). Worldwide variation in human growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feinstein, C. H. (1998). Pessimism perpetuated: Real wages and the standard of living in Britain during and after the industrial revolution. Journal of Economic History, 58, 625–658.

Flinn, M. W. (1974). Trends in real wagers, 1750–1850. Economic history review, 2nd series. 27, 3, 395–413.

Floud, R., Fogel, R. W., Harris, B., & Hong, C. (2011). The changing body. Health, nutrition and human development in the western world since 1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Floud, R., Fogel, R. W., Harris, B., & Hong, S. C. (Eds.). (2014). Health, mortality and the standard of living in Europe and North America since 1700. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Floud, R., & Harris, B. (1997). Health, height and welfare: Britain 1700–1980. In R. Steckel & R. Floud (Eds.), Health and welfare during industrialization (pp. 91–126). Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Fogel, R. W. (1989). Without consent or contract: The rise and fall of American Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Fogel, R. W., & Engerman, S. L. (1974). Time on the cross. The economics of American Negro Slavery. Boston-Toronto: Little, Brown and Company.

Fogel, R. W., Engerman, S. L., & Trussell, J. (1982). Exploring the uses of data on height: the analysis of long-term trends in nutrition, labor, welfare and labor productivity. Social Science History, 6, 401–421.

Fraser, H. (1993). Municipal socialism and social policy. In R. J. Morris & R. Rodger (Eds.), The Victorian city (pp. 258–280). London: Longman.

García-Gómez, J. J. (2013). El nivel de vida de los trabajadores de Alcoy (1836–1936). Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Alicante.

García-Gómez, J. J. (2016). Urban penalty en España: el caso de Alcoy (1857–1930). Historia Industrial, 63, 49–78.

García-Gómez, J. J., & Salort, S. (2014). La reforma sanitaria en Alcoi (1836–1914): Industrialización, urbanización, fallos de mercado e intervención pública. Historia Social, 80, 95–112.

Gutiérrez, M. (2011). Papel de fumar y mercado exterior: la historia de un éxito. In J. Catalán, J. A. Miranda, & R. Ramón-Muñoz (Eds.), Distritos y clústeres en la Europa del sur (pp. 37–56). Madrid: LID Editorial Empresarial.

Haines, M. (2001). The urban mortality transition in the United States, 1800–1940. Annales de Démographie Historique, 101(1), 33–64.

Haines, M. (2004). Growing incomes, shrinking people—Can economic development be hazardous to your health? Historical evidence for the United States, England, and the Netherlands in the nineteenth century. Social Science History, 28(2), 249–270.

Harris, B. (2004). The origins of the British Welfare State Society, State and Social Welfare in England and Wales, 1800–1945. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Horlings, E., & Smits, J. P. (1998). The quality of life in the Netherlands: 1800–1913. Experiments in measurement and aggregation. In J. Komlos & J. Baten (Eds.), Studies on biological standard of living in comparative perspective (pp. 321–343). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Kearns, G. (1988). The urban penalty and the population history of England. In A. Brandström & L. G. Tederbrand (Eds.), Society, Health and Population during the Demographic Transition (pp. 213–235). Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell International.

Kearns, G. (1991). Biology, class, and the urban penalti. In G. Kearns & C. J. Withers (Eds.), Urbanising Britain: Essays on class and community in the nineteenth century (pp. 12–30). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Komlos, J., & Baten, J. (1998). The biological standard of living in comparative perspective. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner.

Krugman, P., Wells, R., & Graddy, K. (2007). Economics (European ed.). New York: Worth Publishers.

Lana Berasaín, J. M. (2005). Aproximación a los salarios reales en la Navarra rural, 1785–1945. VIII Congreso de la Asociación Española de Historia Económica. http://www.usc.es/es/congresos/histec05/a1.jsp.

Lindert, P., & Williamson, J. (1983). English workers living standards during the industrial revolution: A new look. Economic History Review, 36(1), 1–25.

Luckin, B. (2000). Pollution in the city. In M. Daunton (Ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, 1840–1950 (Vol. III, pp. 207–228). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maluquer, J. (2006). La paradisíaca estabilidad de la anteguerra. Elaboración de un índice de precios de consumo en España, 1830–1936. Revista de Historia Económica, 24(2), 333–382.

Martínez-Carrión, J. M., & Puche, J. (2011). La evolución de la estatura en Francia y en España, 1770–2000. Balance historiográfico y nuevas evidencias. Dynamis, 31(2), 153–176.

Meier, G. M. (1980). Leading issues in economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Molina de Dios, R. (2003). Treball intensiu, treballadors polivalents. (Treball, salaris i cost de la vida, Mallorca, 1860–1936). Mallorca: Govern de les Illes Balears.

Mooney, G. (1994). The geography of mortality decline in Victorian London. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Moreno Lázaro, J. (2006). El nivel de vida en la España atrasada entre 1800 y 1936. El caso de Palencia. Investigaciones de Historia Económica, 4, 9–50.

Morris, M. D. (1979). Measuring the condition of the world’s poor. The Physical Quality of Life Index. New York: Overseas Development Council.

Myrdal, G. (1974). Contribución a una teoría más realista del crecimiento y el desarrollo económico. Trimestre Económico, 161, 217–229.

Nadal, J., (dir.). (2003). Atlas de la industrialización de España, 1750–2000. Barcelona: Crítica.

Nicolau, R. (2005). Población, salud y actividad. In A. Carreras & X. Tafunell (Eds.), Estadísticas históricas de España (siglos XIX y XX) (pp. 77–154). Bilbao: Fundación BBVA.

Nordhaus, W., & Tobin, J. (1973). Is growth obsolete? In M. Moss (Ed.), The measurement of economic and social performance (pp. 509–564). New York: Columbia University Press.

Pérez Castroviejo, P. (2006). Poder adquisitivo y calidad de vida de los trabajadores vizcaínos, 1876–1936. Revista de Historia Industrial, 30(1), 103–143.

Popkin, B. M. (1993). Nutrition patterns and transitions. Population and Development Review, 19, 138–157.

Preston, S. H., & van de Walle, E. (1978). Urban French mortality in the nineteenth century. Population Studies, 32, 275–297.

Puche Gil, J. (2009). Evolución de los niveles de vida biológicos en la Comunidad Valenciana, 1840–1948. Unpublished Doctoral thesis.

Pujol, J., & Cussó, X. (2014). La transición nutricional en Europa occidental, 1865–2000: una nueva aproximación. Historia Social, 80, 133–155.

Reher, D. S. (1990). Urbanization and demographic behaviour in Spain, 1860–1930. In A. Woude et al. (Eds.), Urbanization in history: A process of dynamic interactions (pp. 282–299). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Samuelson, P. A. (1983). Economía. Madrid: Mac Graw-Hill.

Schofield, R., Reher, D. S., & Bideau, A. (Eds.). (1991). The decline of mortality in Europe. Oxford: Claredon Press.

Scholliers, P. (Ed.). (1989). Real wages in 19th and 20th century Europe. Historical and comparative perspectives. Oxford: Berg.

Sen, A. (1993). The quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sheard, S., & Power, H. (Eds.). (2000). Body and city: histories of urban public health. Historical Urban Studies. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Smith, L. B., Rosen, K. T., & Fallis, G. (1988). Recent developments in economic models of housing markets. Journal of Economic Literature, 26(1), 29–64.

Steckel, R. (1995). Stature and the standard of living. Journal of Economic Literature, 33(4), 1903–1940.

Steckel, R., & Floud, R. (Eds.). (1997). Health and welfare during industrialization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1993). Economics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2010). Mismeasuring our lives. New York: The New Press.

Szreter, S. (2002a). A central role for local government? The example of late Victorian Britain. History & Policy. http://www.historyandpolicy.org/.

Szreter, S. (2002b). The relationship between public health and social change. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 722–725.

Szreter, S. (2002c). Health, class, place, and politics: Social capital and collective provision in Britain. Contemporary British History, 16, 27–57.

Szreter, S. (2005). Health and wealth: Studies in history and policy. Rochester studies in medical history. Rochester: Rochester University Press.

Szreter, S., & Mooney, G. (1998). Urbanization, mortality, and the standard of living debate: New estimates of the expectation of live in nineteenth century British cities. Economic History Review, 51, 84–112.

Tanner, J. M. (1990). Foetus into man: Physical growth from conception to maturity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Torró Gil, L. L. (1994a). Sobre la protoindustrialització. Reflexions a partir d’un cas local, Alcoi (segles XVI–XIX). Afers. Fulls de recerca i pensament, 19, 661–680.

Torró Gil, L. L. (1994b). Los inicios de la mecanización en la industria lanera de Alcoi. Revista de Historia Industrial, 11(6), 133–142.

Torró Gil, L. L. (2004). Procedimientos técnicos y conflictividad gremial: el ancho de los peines de los telares alcoyanos (1590–1797). Revista de Historia Industrial, 25, 165–182.

Vazquez, E., Camaño, F., Silvi, J., & Roca, A. (2003). La tabla de vida: una técnica para resumir la mortalidad y la sobrevivencia. Boletín epidemiológico Organización Mundial de la Salud, 24(4), 6–10.

Vögele, J. (1998). Urban mortality change in Britain and Germany, 1870–1913. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Vögele, J. (2000). Urbanization and the urban mortality change in imperial Germany. Health & Place, 6, 41–55.

Woods, R. (2000). The demography of victorian England and Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Woods, R. (2003). Urban-rural mortality differentials. An unresolved debate. Population and Development Review, 29, 29–46.

Woods, R., & Woodward, J. (Eds.). (1984). Urban disease & mortality in nineteenth-century England. London: Batsford Academic and Educational.

Woodward, J. (1984). Medicine and the city: the nineteenth century experience. In R. Woods & J. Woodward (Eds.), Urban disease and mortality in nineteenth-century England (pp. 65–78). London: Batsford.

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the Ministry of Economy of the Spanish Government through the Projects HAR2014-56428-C3-1-P, HAR2014-56428-C3-2-P and by Santander Universidades through the Grants Programa Becas Iberoamérica, Jóvenes Profesores e Investigadores y Alumnos de Doctorado. Santander Universidades. España, 2014 and 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: The section 5 was missed out and the Conclusions part was published incorrectly. Now the section 5 is included and correct Conclusions section has been provided in this erratum.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-Gómez, J.J., Escudero Gutierrez, A. The Standard of Living of the Workers in a Spanish Industrial Town: Wages, Nutrition, Life Expentancy and Heigth in Alcoy (1870–1930). Soc Indic Res 140, 347–367 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1776-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1776-0