The Econ tribe occupies a vast territory in the far North. Their land appears bleak and dismal to the outsider, and travelling through it makes for rough sledding; but the Econ, through a long period of adaptation, have learned to wrest a living of sorts from it. (…) The extreme clannishness, not to say xenophobia, of the Econ makes life among them difficult and perhaps even somewhat dangerous for the outsider. This probably accounts for the fact that the Econ have so far not been systematically studied. Information about their social structure and ways of life is fragmentary and not well validated. More research on this interesting tribe is badly needed.

Axel Lejonhufvud (1973, p. 327) our italics

Abstract

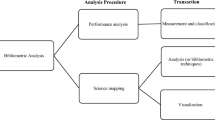

Increased specialization and extensive collaboration are common behaviours in the scientific community, as well as the evaluation of scientific research based on bibliometric indicators. This paper aims to analyse the effect of collaboration (co-authorship) on the scientific output of Italian economists. We use social network analysis to investigate the structure of co-authorship, and econometric analysis to explain the productivity of individual Italian economists, in terms of ‘attributional’ variables (such as age, gender, academic position, tenure, scientific sub-discipline, geographical location), ‘relational’ variables (such as propensity to cooperate and the stability of cooperation patterns) and ‘positional’ variables (such as betweenness and closeness centrality indexes and clustering coefficients).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The empirical evidence for both arguments is mixed. In terms of quantity, McDowell and Smith (1992) use cross-sectional data on academics and regress the number of articles produced by an individual (with co-authored articles discounted by the number of authors) on the percentage of co-authored articles and find no significant result. Durden and Perri (1995) use time series data for annual economics publications, over 24 years, and find that the total number of publications is positively related to the number of co-authored publications. Hollis (2001) uses the same data, and regresses total publications on the proportion that is co-authored, and finds no significant relationship. He then employs panel data for 339 individuals (US and Canadian AEE members) and finds that, if publications are discounted by number of authors, ‘adding one more author is associated with a per capita reduction in output of between 7% and 20%’ (Hollis 2001, p. 527).

In terms of quality also, the empirical evidence is mixed. Laband and Tollison (2000) document an acceptance rate of 12% for collaborative papers submitted during the mid-1980s to the Journal of Political Economy, compared to 10% for single-authored papers. Others, such as Laband (1987), measure quality by citation frequency and report that this index is significantly higher for co-authored articles, while Barnett et al. (1988) use the positioning of the article in the journal as the signal of quality and find no support for this argument.

These cites theoretically support the inclusion of a series of network analysis indexes in the empirical part of this paper, to take account of both the attributional features of each author and his/her relational and positional characteristics.

‘Interdisciplinary research also should be characterized by high rates of co-authorship by the same reasoning. The Piette–Ross insight, coupled with economists' steadily increasing colonization of other disciplines during the latter half of the twentieth century, may ex-plain a significant portion of the increase in the incidence of co-authorship’ (Laband and Tollison 2000, p. 640).

‘It may be cheaper for an individual to acquire new capacity (human capital) to produce through formal collaboration (merger) with someone who already has the requisite human capital than to acquire the needed knowledge de novo, personally’ (Laband and Tollison 2000, pp. 639–640).

‘The development of technology has made collaboration more accessible across time and space. Overnight mail, photocopiers, computers, fax machines, email, and teleconferencing make long-distance collaboration considerably less daunting and time consuming. In essence, the invisible college of the 1960 s and 1970 s has been replaced by the “virtual college,” or, more appropriately, the “virtual research center,” of today’ (Fisher et al. 1998, pp. 847–848; Kretschmer 1994). In order to detect the relevance of networks in publishing, an interesting perspective on the analysis of the editorial boards has been conducted by Baccini and Barabesi (2010).

As for the effects of ICT on co-authorship patterns, Butler (2007) shows that (at least for a subsample of American Economic Association members working in the JEL fields D8, G2 and J3) the rate of internet penetration moved from almost nothing in 1995 to around 60 % in 1997, and to almost 100 % in 1999; while Maggioni et al. (2009) show that the average distance between co-authors working on the issue of ‘industrial clusters’, increased continuously in the period 1969–2007.

These positions in Italian are: Professore Ordinario, Professore Straordinario, Professore Associato Confermato, Professore Associato, Ricercatore Confermato, Ricercatore. There is another position, Assistente Ordinario, which is between a lecturer and a professor whose academic duties are similar to a senior lecturer. Since this position is increasingly disappearing (percentage is only around 1%), we code this as SL. See Appendix A1 and Cainelli et al. (2006) for more details.

The law is contained in the Decreto Ministeriale 4 ottobre 2000 and published in the G.U. n. 249 del 24 ottobre 2000—supplemento ordinario 175.

Economics also includes Political Economy and Economic Policy (i.e. corresponding to the disciplinary sectors SECS-P/01 Economia Politica, SECS P/02 Politica Economica), Econometrics refers to the disciplinary sector SECS-P/05 Econometria, Public Economics to SECS-P/03 Scienza delle Finanze, and Others is a miscellaneous disciplinary sector which includes SECS-P/04 Storia del Pensiero Economico (History of Economic Thought), and SECS-P/06 Economia Applicata, a mix of regional economics, transport economics, and industrial organization.

Econlit distinguishes between different “scientific products”: journal articles, collective volume articles, books, working papers and dissertations.

The focus on JA reflects the overwhelming role played by these “products” in the recent evaluation procedures (CIVR, VQR) put forward by individual universities and the Ministry.

By using Econlit as bibliographic database, we focus at the quantitative profile of the internationally-visible scientific production of Italian economists, but we do not measure the “scientific value” of their publications. Although this might be considered a significant shortcoming, we do not believe to be as serious as the dominant faction in the current debate on evaluation might suggest. We are in fact convinced that the issue of how to weigh publications, and particularly the use of impact factors or citation indexes, should still be considered an open question for economics, as suggested by the results of the evaluation of European economics departments carried out by the European Economic Association (see Neary et al. 2003a, b).

The 19 foreign economists affiliated to Italian universities in the economics fields, in this paper are considered to be ‘Italian economists’.

The affiliations can be worldwide: this selection includes individuals with both foreign and Italian affiliations (i.e. individuals from other scientific sectors not included in those defined in “The original database”, or institutions outside academia, i.e. Banca d’Italia, CNR, ISTAT, etc.).

We should stress that 41 individuals in the M population have entries in the Econlit database that do not refer to JA.

Since we are interested in investigating differences in the collaborative behaviour of Italian economists in scientific collaborations with native academics and collaborations with foreigners, and since researchers are often quite mobile (and may change affiliations in the course of their careers), we attribute the residual population to sub-sets F or O based on nationality.

For connected networks, the range is between 0 (i.e. the network is minimally connected, meaning that the removal of just 1 link would disconnect the whole network) and 1 (i.e. the network is complete, meaning all possible links already exist).

It is useful to recall that a large random network (Erdős and Renyi 1959) is characterized by a binomial degree distribution, while CC—which depends on the size of the network—is equal to the ratio of average degree and number of nodes, and APL and δ depend on the size of the network structure and its average degree (Albert and Barabasi 2002).

Similarly it is possible randomly to remove some nodes in order compare the main components of the real network with the equivalent random ones (Maggioni and Uberti 2009).

In a ‘small world’ structure, the path between two nodes in very large network may be extremely short due to the existence of bridging agents. This means that even in very large and locally clustered networks efficient and fast information diffusion is possible.

In the paper we compute Q sw for the whole network (from 1969 to 2006) as well as for the last two sub-periods when a main component emerged in the network structure.

These networks are characterized by a very skewed degree distribution with very few pivotal nodes, and a large number of peripheral nodes.

Degree, betweenness and closeness centralities are calculated as defined by Freeman (1979).

On the basis of the degree centrality index of each node, we computed a network index, average degree (av_deg), as the mean value of the degrees (i.e. directly incident links) of each node in the network, in order to enable comparison of the collaborative behaviours of Italian academic economists in different time periods.

Relative density is negative, signalling the existence of isolated nodes.

We should remember that the denominator of density measures increases non-linearly (n*n − 1) with network size n.

Thus we did not compute the index for periods 1 and 2.

Specifically, we use the dprobit model. Rather than reporting coefficients, dprobit reports the marginal effects, i.e. the change in the probability for an infinitesimal change in each independent, continuous variable and, by default, reports discrete change in the probability of the dummy variables.

This has been used as the reference and not included in the regression.

This has been used as the reference and not included in the regression.

We should remark that we do not compute the individual share of each co-author in an article, in other words we do not capture the individual contributions’ of each economist to a given paper in order not to introduce arbitrary corrections in our regressions given that within certain research fields—such as economic and econometric theory, history of economic thought, economic history—the number of co-authors tends to be systematically lower than in applied economics.

E.g. for an individual i who published his/her first article in an Econlit indexed journal in 1985, the “seniority” is calculated as 2006–1985 = 21.

Calculated to distinguish each person’s identity.

When the coefficient on the inverse Mill’s ratio is negative this means that there are unobserved variables increasing the probability of selection and the probability of a lower than average score on the dependent variable.

Even if we cannot exclude that the liaison with members of the editorial boards of international journals might also play an important role in the publication processes.

These values are calculated exclusively on the MC of the co-authorships network dichotomized according to a threshold value greater than zero.

This value is calculated for each individual based on the aggregated network of the Italian economist community for the whole period 1969–2006.

In general SNA terms, if the neighbors of a single node are also neighbors of each other (i.e. if the clustering coefficient of that node is high), these neighbors are not reliant on the single node for their connection. Therefore, the intermediate node is completely needless for the connection between these two neighbors.

These are Gender, Tenured, and controls such as North West, North East, Centre, South, Islands, Age97_06, Age87_96, Age77_86, Age69_76.

This is one of the reasons for omitting the most common measure of centrality (degree centrality index) in our case equal to the number of previous co-authors, which is easily observed by the individual researcher: the other reasons are multicollinearity with other measures of centrality.

“Thus the most connected individuals collaborated extensively and most of their co-authors did not collaborate with each other. The most connected individuals can be viewed as `stars' from the perspective of the network architecture” (Goyal et al. 2006, p. 412).

References

Acedo, F. J., Barroso, C., Casanueva, C., & Galàn, J. L. (2006). Co-authorship in management and organizational studies: An empirical and network analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 43(5), 957–983.

Albert, R., & Barabasi, A. L. (2002). Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Reviews of Modern Physics, 74(1), 47–99.

Baccini, A., & Barabesi, L. (2010). Interlocking editorship. A network analysis of the links between economic journals. Scientometrics, 82(2), 365–389.

Barnett, A. H., Ault, R. W., & Kaserman, D. L. (1988). The rising incidence of co-authorship in economics: Further evidence. Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(3), 539–543.

Borgatti, S. P., & Everett, M. G. (1997). Network analysis of 2-mode data. Social Networks, 19(3), 243–269.

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Burt, R. S. (2004). Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology, 110(2), 349–399.

Butler, R. J. (2007). JRI, JF, and the Internet: Coauthors, new authors, and empirical research. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 74(3), 713–737.

Cainelli, G., de Felice, A., Lamonarca, M., & Zoboli, R. (2006). The publications of Italian economists in ECONLIT. Quantitative assessment and implications for research evaluation. Economia politica. Journal of Analytical and Institutional Economics, 23(3), 385–423.

Cainelli, G., Maggioni, M. A., Uberti, T. E., & de Felice, A. (2012). Coauthorship and productivity among Italian economists. Applied Economic Letters, 19(16), 1609–1613.

Dolado, J. J., Garcia-Romero, A., & Zamarro, G. (2003). Publishing performance in economics: Spanish rankings (1990–1999). Spanish Economic Review, 5(4), 85–100.

Doreian, P., Batagelj, V., & Ferligoj, A. (2004). Generalized blockmodeling of two-mode network data. Social Networks, 26(1), 29–53.

Durden, G. C., & Perri, T. J. (1995). Coauthorship and publication efficiency. Atlantic Economic Journal, 23(1), 69–76.

Erdős, P., & Rényi, A. (1959). On random graphs. Publicationes Mathematicae, 6, 290–297.

Fafchamps, M., Goyal, S., & van der Leij, M. J. (2010). Matching and network effects. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(1), 203–231.

Fafchamps, M., van der Leij, M.J., & Goyal, S. (2006). Scientific networks and co-authorship. Economics. Oxford: Working Papers, University of Oxford, p. 256.

Fisher, B. S., Cobane, C. T., Ven Vander, T. M., & Cullen, T. M. (1998). How many authors does it take to publish an article? Trends and patterns in political science. Political Science and Politics, 31(4), 847–856.

Fleming, L., Mingo, S., & Chen, D. (2007). Brokerage and collaborative creativity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 443–475.

Freeman, L. C. (1979). Centrality in social networks. Conceptual Clarification. Social Networks, 1(3), 215–239.

Goyal, S. (2005). Strong and weak links. Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2–3), 608–616.

Goyal, S. J., van der Leij, M., & Moraga-Gonzalez, J. L. (2006). Economics: An emerging small world. Journal of Political Economy, 114(2), 403–432.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Hilmer, C. E., & Hilmer, M. J. (2005). How do journal quality, co-authorship, and author order affect agricultural economists’ salaries? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87(2), 509–523.

Holder, M., Langrehr, F., & Schroeder, D. (2000). Finance journal co-authorship: How do co-authors in very selected journals evaluate the experience? Financial Practice and Education, 10(1), 142–152.

Hollis, A. (2001). Co-authorship and the output of academic economists. Labour Economics, 8(4), 503–530.

Hudson, J. (1996). Trends in multi-authored papers in economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(3), 153–158.

Johnston, D. W., Piatti, M., & Torgler, B. (2013). Citation success over time: Theory or empirics? Scientometrics, 95, 1023–1029.

Kalaitzidakis, P., Mamuneas, T. P., & Stengos, T. (1999). European economics: An analysis based on publications in the core journals. European Economic Review, 43(4–6), 1150–1168.

Kretschmer, H. (1994). Coauthorship networks of invisible colleges and institutionalized communities. Scientometrics, 30(1), 363–369.

Laband, D. N. (1987). A Quantitative test of journal discrimination against women. Eastern Economic Journal, 13, 149–154.

Laband, D., & Piette, M. J. (1995). Team production in economics: Division of labour or mentoring. Labour Economics, 2(1), 33–40.

Laband, D., & Tollison, R. (2000). Intellectual collaboration. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 632–661.

Laband, D., & Tollison, R. (2006). Alphabetized co-authorship. Applied Economics, 38(14), 1649–1653.

Lee, S., & Bozeman, B. (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science, 35(5), 673–702.

Liebowitz, S. J., & Palmer J. P. (1983). Assessing assessments of the quality of economics departments, manuscript. Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester.

Maggioni, M. A. (1995). Metodologie reticolari per l’analisi dei sistemi locali di produzione e innovazione. Economia and Lavoro, 29(1/2), 109–130.

Maggioni, M. A., Gambarotto, F., & Uberti, T. E. (2009) Mapping the Evolution of Clusters. A Meta-Analysis. Milano: Working Papers, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, p. 74.

Maggioni, M. A., & Uberti, T. E. (2009). Knowledge networks across Europe: Which distance matters? Annals of Regional Science, 43(3), 691–720.

Maggioni, M. A., & Uberti, T. E. (2011). Networks and geography in the economics of knowledge flows. Quality & Quantity, 45(5), 1031–1051.

McDowell, J. M., & Melvin, M. (1983). The determinants of co-authorship: An analysis of the economics literature. Review of Economics and Statistics, 65(1), 155–160.

McDowell, J. M., & Smith, J. (1992). The effect of gender-sorting on propensity to coauthor: Implications for academic promotion. Economic Inquiry, 30(1), 68–82.

Medoff, M. H. (2003). Collaboration and the quality of economics research. Labour Economics, 10(5), 597–608.

Neary, J. P., Mireless, J. A., & Tirole, J. (2003a). Evaluating economics research in Europe: An introduction. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(6), 1239–1249.

Neary, J. P., Mireless, J. A., & Tirole, J. (2003b). Evaluating economics research in Europe: An introduction. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(6), 1239–1249.

Newman, M. E. J. (2001). The structure of scientific collaboration networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 404–409.

Newman, M. E. J. (2003). The structure and function of complex networks. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics Review, 45(2), 167–256.

Nowell, C., & Grijalva, T. (2011). Trends in co-authorship in economics since 1985. Applied Economics, 43(iss. (28-30)), 4369–4375.

Piette, M. J., & Ross, K. L. (1992). An analysis of the determinants of co-authorship in economics. Journal of Economic Education, 23(3), 277–283.

Sauer, R. (1988). Estimates of the returns to quality and co-authorship in economic academia. Journal of Political Economy, 96(4), 855–866.

Sigelman, L. (2009). Are two (or three or four … or nine) heads better than one? Collaboration, multidisciplinarity, and publishability. Political Science and Politics, 42(3), 507–512.

Strogatz, S. (2001). Exploring complex networks. Nature, 410, 268–276.

Sutter, M., & Kocher, M. (2004). Patterns of co-authorship among economists in the USA. Applied Economics, 36(4), 327–333.

Ter Wal, A. L. J., & Boschma, R. A. (2009). Applying social network analysis in economic geography: Framing some key analytic issues. Annals of Regional Science, 43(3), 739–756.

Uzzi, B., & Spiro, J. (2005). Collaboration and creativity: The small world problem. American Journal of Sociology, 111(2), 447–504.

van der Leij, M., & Goyal, S. (2011). Strong ties in a small world. Review of Network Economics, De Gruyter, 10(2), 1–22.

Vieira, P. C. C. (2008). An economics journals’ ranking that takes into account the number of pages and co-authors. Applied Economics, 40(7), 853–861.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Watts, D. (1999). Small worlds: The dynamics of networks between order and randomness. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cainelli, G., Maggioni, M.A., Uberti, T.E. et al. The strength of strong ties: How co-authorship affect productivity of academic economists?. Scientometrics 102, 673–699 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1421-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1421-5