Abstract

This article examines how the legacies of the past in peripheral post-industrial places serve to shape current and future entrepreneurial activity, and with it local economic resilience. Drawing on in-depth qualitative interviews with key regional stakeholders, the article reveals how peripheral post-industrial places are constrained by their histories. This is found to be manifest in different ways, such as low aspirations, generational unemployment and a loss of identity which are in turn compounded by negative perceptions of place and opportunity. These issues culminate in institutional hysteresis at the local level and constrain entrepreneurial ambition. The article argues that the rigidity and reproduction of informal institutions continues to stymie economic resilience and growth. We conclude by reflecting on the implications for entrepreneurship in peripheral post-industrial places as well as with recommendations for policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

One of the key questions in the social sciences is why some local and regional economies are more capable of renewal and transformation than others which remain locked in decline or underperformance (Hassink 2010; Martin and Sunley 2014). During the 1970s and 1980s, industrial regions saw large sections of their industry and manufacturing destroyed (Martin 2012). However, there is significant variation in regional responses to the effects of deindustrialisation, and while some regions have recovered positively, others continue to be constrained by its persisting negative effects (Cowell 2013).

For decades, governments have attempted to stimulate economic regeneration in former industrial regions (Burch et al. 2009), of which enterprise policy has sought to promote and foster entrepreneurship as an engine of economic growth (Curran 2000; Williams and Vorley 2014). However, Arshed et al. (2014) highlight that the formulation of enterprise policy is often guided by political interest rather than being underpinned by robust evidence, which can lead to ‘policy-based evidence making’ as opposed to employing ‘evidence-based policy making’. Moreover, enterprise policy in the UK has been conceived nationally with little sensitivity to local contexts (Huggins and Williams 2011), and consequently achieved little in reducing spatial and socio-economic disparities (Gardiner et al. 2013). Indeed, there has in fact been a widening of the divide between core and peripheral economic places (Mason et al. 2015), not only at the interregional but also intraregional level. This highlights the necessarily heterogeneous local responses in adapting to shocks.

Entrepreneurship research has highlighted that entrepreneurial outcomes are sensitive to institutional contexts (Estrin et al. 2016), with formal and informal institutions influencing the decisions of individuals to pursue entrepreneurial activity (Williams and Vorley 2015). However, while formal institutions may seek to promote entrepreneurship and resilience, informal institutions can pull in the opposite direction (Dennis 2011). Institutional research has shown that ‘history matters’ (Martin 2012), and informal institutions serve as ‘carriers of history’ (Pejovich 1999) which can be resistant to change. Where informal institutions are rigid, they can lead to institutional hysteresis, which occurs when institutions are self-reproducing and changing slowly over time (Martin and Sunley 2006). Hysteresis is often the outcome of ‘one-time disturbances [that] permanently affect the path of the economy’ (Romer 2001 p.471), of which deindustrialisation is a typical example (Martin 2012). Rigid informal institutions can also stymie entrepreneurship and undermine local economic resilience as they ‘can end up creating vicious circles of suboptimal development trajectories’ (Rodríguez-Pose 2013, p.1041). However, hysteresis has hitherto been studied mainly within the economic sphere, many studies emphasising the economic level impact of shocks (see, for example, Cross 1993; Cross et al. 2012; Martin 2012), and therefore less is known about how hysteresis manifests at the institutional level. Moreover, while previous research has highlighted variations in regional economic resilience (see, for example, Martin 2012; Pike et al. 2010), this article addresses the question of intraregional variation in economic resilience with a focus on the less researched local scale (Dawley et al. 2010).

The article contributes to these debates with a focus on peripheral post-industrial places (PPIPs). The term refers to places outside of major urban centres whose continued underperformance is the result of persisting effects of deindustrialisation, and as such have been unable to make what Hall (2008) describes as the ‘critical transition’ beyond the manufacturing economy. As they seek to embark on economic renewal, PPIPs face the dual challenge of peripherality and (negative) path dependency which maintains their status as peripheral. The article analyses how the local institutional environment has shaped entrepreneurial activity in PPIPs, focusing specifically on the impact of informal institutions. Previous research at the regional scale has emphasised the lower level of entrepreneurship in such places (see, for example, Greene et al. 2004; Mueller et al. 2008; Stuetzer et al. 2016). We find that in PPIPs this is the result of rigid informal institutions which culminate in institutional hysteresis at the local level, constraining entrepreneurship and undermining local economic resilience. As Martin (2012, p.28) highlights, a full explanation of why some local economies are more resilient than others ‘would need to analyse the reactions and adjustments of both firms and workers at the local level, as well as the reactions of local institutions and policy actors’. By highlighting the lack of adaptation of local informal institutions to deindustrialisation and the subsequent policy response, we contribute to a better understanding of why some places are more resilient than others.

Therefore, the central research question informing this article is ‘how do informal institutions affect entrepreneurship and local economic resilience in peripheral post-industrial places?’. In exploring this question, we find that policy attempts to stimulate entrepreneurial-led growth in PPIPs were hindered by an asymmetry between national and local level institutions, with local level informal institutions being unfavourable to entrepreneurship. The article shows that while national level formal institutions seek to foster entrepreneurship and resilience, local level informal institutions can pull in the opposite direction, meaning that neither entrepreneurship nor resilience is enhanced. As such, one potential way to address the challenges faced by PPIPs is through local governance and policy which reflects the needs of the locality. With increasing discrepancies between core cities and peripheral towns (Hall 2008), it is critical that policy adopts a more contextual approach to address the issues which create hysteresis and to promote entrepreneurship as a key factor underpinning economic regeneration and resilience. The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 situates the article in the institutional literature, Section 3 introduces the empirical focus and methodology, Section 4 presents an analysis and discussion of the findings, and Section 5 concludes, reflecting on implications of the study and areas for further research.

2 Literature review

2.1 The importance of institutions for entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is sensitive to the institutional context (Estrin et al. 2016), with the role of formal and informal institutions critical in determining the level of entrepreneurial activity (Acs et al. 2008). Formal institutions are the formally accepted rules and regulations that define the economic and legal framework of a society, while informal institutions are the unwritten rules and include customs, norms, values and conventions that are socially engrained (Acs et al. 2008; Williams and Vorley 2017). As such, it is the interplay and arrangement of formal and informal institutions that shapes social action, and with it entrepreneurial activity. When formal and informal institutions are mutually reinforcing, they create a virtuous circle, thereby fostering (more) productive entrepreneurship (Dennis 2011). Conversely, where institutional arrangements are asymmetric this can create tensions which stymie entrepreneurship. The prevailing alignment or asymmetry of institutions will affect entrepreneurship in different contexts (Williams and Vorley 2015), although little is understood about the differential impacts at the national and local levels.

Informal institutions are ‘the old ethos, the hand of the past, or the carriers of history’ (Pejovich 1999, p. 166), meaning that past events leave an institutional imprint causing institutions to change slowly over time. This emphasises the perspective that ‘history matters’, creating a path dependency where places are unable to ‘shake free of their history’ (Martin 2012, p.399). The consequence of this, as echoed by Hayter (2004) is that present and future socio-economic activity is shaped by past outcomes. However, as highlighted by Martin and Sunley (2006), path dependence can have different causes, such as technological lock-in, dynamic increasing returns where positive feedback reinforces existing development paths, and the tendency of informal institutions to be self-reproducing over time which culminates in institutional hysteresis. Thus, hysteresis is itself a form of path dependence and can manifest as a product of historical time (Setterfield 1993; Tubadji et al. 2016), creating a path dependence that is ‘grounded in the reproduction of instituted forms of behaviour’ (Hudson 2005, p.583). Indeed, institutional hysteresis manifests as the continuous reproduction of institutions ‘even if the original conditions that caused their creation might have long disappeared’ (Bathelt and Glückler 2014, p.9). However, in the case of institutional hysteresis, not all history matters. Extreme experiences (e.g., major socio-economic shocks) often inflict structural changes and can influence the behaviour of economic agents, hence the display of ‘selective memories’ characterising places affected by institutional hysteresis (Setterfield 2010), with the ‘memory’ of the shock persisting through a process known as ‘remanence’ (Grinfeld et al. 2009). In relation to institutions, Sztompka (1996, p.126) explains that the self-reproducing nature of informal institutions, and hence ‘remanence’, is determined by the ‘generational effect’, as ‘the bridge between the influences of the past and the future is provided by generations … who–in their formative years–have happened … to have lived through similar, significant social events’. For example, as Byrne (2002) highlights, industrialism became so engrained in the social fabric of industrialised places that these developed an industrial ‘way of life’. Thus, informal institutions developed around mass employment in large-scale industries as opposed to self-employment, and the absence of an entrepreneurship culture has seen such places facing difficulties in adapting to a post-industrial setting that emphasises entrepreneurial-led growth (Stuetzer et al. 2016).

Institutions develop in relation to place (Bathelt and Glückler 2014). As such, being socially engrained, informal institutions tend to vary from place to place, hence why different contexts determine institutional variety as opposed to homogeneity (Bathelt and Glückler 2014; Hayter 2004), which can affect the how formal institutional changes are adopted and implemented. Therefore, as Bristow (2010) asserts, ‘place matters’, meaning that the nature of path dependence is locally contingent and requires a geographical explanation (Martin and Sunley 2006). As such, due to the particularities of local institutional structures (Martin 2000), institutional hysteresis needs to be understood as a place-dependent process. The local variation of informal institutions means that the interplay between formal and informal institutions can be a potential cause of institutional hysteresis, with institutions incongruent at the national and local level. We argue that it is the slow changing nature of informal institutions, manifested through institutional hysteresis, which hinders change and affects the translation of national level institutions to the local level, hence why national level enterprise policies oftentimes only generate a limited economic impact at the local level and why some places are more resilient than other.

2.2 The impact of hysteresis on entrepreneurship and resilience at the local level

With much of the research on entrepreneurship conducted at the national and regional level, much less is known about the dynamics of entrepreneurship and resilience at the local scale (Dawley et al. 2010). Resilience has relatively recently emerged in the vocabulary of the social sciences, and remains a somewhat fuzzy concept. Martin (2012) summarises the main interpretations of resilience as the ability of a system to ‘bounce back’ to a pre-existing state following a shock; the ability of a system to absorb a shock while maintaining its structure, identity and function, and the ability of a system to anticipate and react to shocks by undergoing structural and operational adaptation. The first two interpretations represent equilibrist approaches, as they imply that responses to shocks involve either returning to an initial equilibrium or moving to a new equilibrium. While these involve stability and persistency of structures, adaptive resilience emphasises the interplay between continuity and change through which adaptation occurs, hence being referred to as evolutionary resilience (Martin and Sunley 2014).

Equilibrist approaches have been criticised on the basis that firms, organisations and institutions are in a continuous state of change and adaptation to their economic environments (Simmie and Martin 2010). Where major shocks result in structural change (Setterfield 2010; Bristow and Healy 2014), the return to a pre-existing state becomes virtually impossible. Instead, adaptive resilience takes account of the heterogeneity characterising local economies and can better explain how local institutions react to shocks, and thus why some economies are more resilient than others (Hassink 2010). Indeed, when shocks inflict structural changes, they transform into ‘slow-burn processes of change’ (Pike et al. 2010, p.5). As such, facing transformation, deteriorating conditions and pressures for institutional change, places affected by ‘slow burns’ face greater challenges in becoming more resilient (Pendall et al. 2010). A typical example is deindustrialisation where the initial shock affecting local economic structures and jobs drifted into a slow-burn process of adaptation to the effects of deindustrialisation (Pike et al. 2010). A major shock such as deindustrialisation creates pressures on institutions and the institutional response at national, regional and local levels (Dawley et al. 2010). As Greene et al. (2004) highlight, the formal institutional response to the negative impact of deindustrialisation has been the promotion of entrepreneurship; however, this has only achieved a limited impact in formerly industrialised places.

Indeed, there is significant intraregional variation in responses to deindustrialisation, with core cities forming ‘islands of economic growth, separated by wide seas of economic stagnation or decline’ (Hall 2008, p. 74). As such, many localities continue to underperform economically and to lack economic resilience. This means that adaptation is geographically uneven, particularly within the ‘wide rings of ex-industrial towns’ surrounding core cities (Hall 2008, p. 73), which can perpetuate pockets of deprivation (Salet and Savini 2015). Similarly, legacies of the past can constrain entrepreneurship, as the post-shock response and recovery of an economy is dependent on the response of local institutions and culture (Martin 2012). A lack of prior exposure to entrepreneurship and low entrepreneurial skills can contribute to hysteresis (Fayolle and Gailly 2015), which will impact on those living in PPIPs. Furthermore, such areas also see limited scale and ambition regarding entrepreneurship (Amoros et al. 2013) and an underdeveloped entrepreneurship culture (Stuetzer et al. 2016). As the self-reproducing nature of institutions can create ‘unchanging cultures’ (Simmie and Martin 2010), institutional hysteresis can serve to limit entrepreneurial activity in PPIPs, thereby constraining the adaptive capacity of a local economy and with it its economic resilience. Indeed, as cultural perceptions and attitudes change much more slowly than economic conditions, there is a persistence of culture related phenomena, although Tubadji et al. (2016) state that this may decrease in impact during a crisis period. However, we find that the continued economic underperformance and constrained level of entrepreneurial activity in PPIPs is the result of rigid informal institutions which culminate in institutional hysteresis at the local level, undermining local economic resilience. As such, we argue that, as economic resilience is premised on adaptive social and institutional arrangements (Martin and Sunley 2014), local economic resilience is inherently linked to institutional resilience at the local level, and that institutional responses have hitherto lacked sensitivity to institutional context, hence the failure of decades of national level policy to create more entrepreneurial and resilient local economies.

Institutional change can occur gradually through the addition of new rules, procedures and structures to existing arrangements and through a reorientation of institutions in terms of form, function, or both (Martin 2010) or by recombining institutional resources to produce new institutional structures (Schneiberg 2007). Nevertheless, highlighting the need to theorise local processes of institutional transformation, Martin (2000, p.86) states that ‘[t]he task for economic geographers is to conceptualize the spatial dimensions of this hysteretic process’ and ‘to determine how far and for what reasons the process of institutional change itself is likely to vary geographically’. We argue that the future economic growth of PPIPs needs to be premised on local processes of institutional transformation, of which we focus specifically on entrepreneurship which has the potential to move the economies away from previous (negative) path dependence.

3 Empirical focus and methodology

The empirical focus of this study is Doncaster, a post-industrial town and one of nine local authorities comprising the Sheffield City Region (SCR) in the North of England. The SCR is one of 37 Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) established as ‘functional economic areas’ intended to deliver tailored local economic strategic priorities and policies (Pugalis and Townsend 2012). However, the SCR is a monocentric region centred around the City of Sheffield while Doncaster is located on the periphery. The SCR LEP has a series of ambitious targets relating to fostering entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial-led growth, although the intraregional variation means that the economic reality of Sheffield is somewhat different to that facing Doncaster. While our focus is on a PPIP in the UK, the local configuration of policy reflects shifts in other economies which seek to empower cities and promote a more localised approach (Ache 2000), and as such lessons can be drawn for international policy and theoretical dimensions.

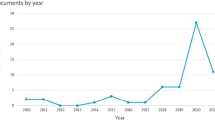

Doncaster, like many other former industrial towns in developed economies, has experienced a decline in traditional manufacturing industries from the mid-1970s, which has led to a prolonged period of economic decline and stagnation (Williams and Vorley 2014). Deindustrialisation resulted in significant job losses, releasing ‘a pool of low-skilled, low-wage labour onto the local labour market’ (Simmie and Martin 2010, p.36), and generating long-lasting effects (Beatty et al. 2007; Martin 2012). Left without economic purpose following deindustrialisation, such places underperform economically, needing both social and economic regeneration (Thompson 2010). In response to Doncaster’s path-dependent evolution, a concerted institutional response has been to foster entrepreneurship. While more recently Doncaster has seen an increase in start-up rates (Table 1), it ranks among the least competitive localities in the UK (Huggins and Thompson 2013) with more than three quarters of its businesses employing less than five people (Table 2), which emphasises the underproductive nature of entrepreneurial activity. Seeking to embark on economic renewal, PPIPs such as Doncaster continue to be constrained by legacies of the past which have weakened their economic resilience. With national level entrepreneurship policy having achieved a limited impact in stimulating entrepreneurial-led growth at the local level, the article sets out to examine the roots and implications of uneven intraregional development and local responses.

The empirical focus of this study involved qualitative research to develop a richer understanding of institutional hysteresis. In-depth interviews are particularly applicable to policy oriented research, as they assist in exploring contextual, diagnostic, evaluative and strategic dimensions, providing rich data (Silverman 2000). A qualitative approach thus enables a greater understanding of how legacies of the past continue to stymie entrepreneurial-led growth in PPIPs. In-depth interviews were conducted with stakeholders who had a key role in shaping entrepreneurship and economic development in Doncaster, following the schedule outlined in Online Resource 1. In total, 14 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders (Table 3), all of whom have a remit for supporting economic regeneration through a more enterprising and resilient local and regional economy. A snowball sampling method was used, with a core group of respondents involved in local development policy and delivery invited to take part, and who then recommended other potential respondents. We acknowledge that snowball sampling is not fully random and subject to selection bias, however this technique also allows the researchers’ high level of attentiveness to the focus of the study as they become immersed in the research area (Biernacki and Waldorf 1981). The approach also ensured that the interviews represented the key stakeholders involved in local policy within Doncaster as well as the wider City Region. Given the political sensitivity of the research and the position of many interviewees in public office, individuals participating in the research remained anonymous.

The interviews were conducted between November 2015 and May 2016 with stakeholders representing institutions in Doncaster and the SCR with the jurisdiction for entrepreneurship and economic growth. In qualitative research, the questions asked can be modified (Frank and Landström 2016), and the nature of semi-structured interviews meant that a number of issues that were not included in the interview schedule and yet were raised by respondents were subsequently explored further. The interviews were recorded with the respondent’s consent and transcribed before assuming a grounded approach towards thematically analysing and coding the data to explore emergent themes. It was important, in keeping with Bryman (2012), that the reliability of coding was consistent and structured in order to prevent coder bias. Therefore, the coding process was conducted independently by the authors, with overarching thematic categories identified to develop a coding scheme based on key themes so that intra-coder reliability could be consistent. This coding scheme was applied by the authors, and the results of it were then compared to ensure inter-coder reliability by identifying any discrepancies between the coders so that they could be revisited and agreed. This constant comparative method involves continually identifying emergent themes against the interview data, and employing analytic induction whereby the researcher identifies the nature of a relationship and develops the narrative (Silverman 2000). In many cases, consensus was found regarding the key areas of exploration and these responses can therefore be considered to be representative of the views of the majority of the respondents. Collectively, the interviews provided a comprehensive overview of the influence of traditional industries on the institutional environment at the local level, as well as deep insights into the impact of deindustrialisation and how its persisting effects continue to constrain entrepreneurial-led growth locally.

4 Findings

In analysing how legacies of the past continue to shape entrepreneurship in PPIPs, this section demonstrates how the long-lasting effects of deindustrialisation have created institutional hysteresis which stymies the development of a more enterprising and resilient local economy. The findings are discussed in relation to three key overarching themes which emerged from the interviews: (1) the socio-economic consequences of deindustrialisation, (2) hysteresis and the institutional environment, and (3) entrepreneurship and institutional transformation.

4.1 The socio-economic consequences of deindustrialisation

The stakeholders highlighted the seismic impact of deindustrialisation which destabilised the local economy of Doncaster, a process in common with other PPIPs, through large-scale job losses and the collapse of communities. Indeed, industrialisation brought economic growth and prosperity to such localities, where economic activity was focused around traditional industries. As a typical industrial town, Doncaster experienced rapid growth in the twentieth century. One stakeholder explains:

‘If you look at the development of these villages 10 years of it opening, they absolutely exploded. What then happened in the 1960’s, there were some government policy around directing jobs into these mining areas, so what you then tended to find was that you’d have a small village of 10,000 people where all the men worked down the pit and then all the women worked in the new textile factories’ (INT1).

The clustering and concentration of coal mining and rail industries in Doncaster, and the associated specialised labour markets and infrastructure, is what gave the town (and the wider region) its competitive advantage (Porter 2000; Martin and Sunley 2003). However, Doncaster’s economy, like other PPIPs, became over-reliant on a small concentration industries, and with it became vulnerable to what Bristow (2010, p.156) highlights as a ‘debilitating stasis caused by over-dependence on key industrial sectors in structural decline’. This was compounded by the inability of Doncaster to innovate and or develop capabilities in related or new industries, as was the case in the City of Sheffield at the core of the region. As the stakeholders emphasised, there was little spare capacity to enable the local economy to adapt in the event of structural change:

‘Up until the late 70’s, early 80’s Doncaster had essentially full employment with big manufacturing firms, a lot of them in the coal industry, and when those industries started to close down and downsize the one thing they didn’t do was actually leave any accommodation’ (INT1).

‘We had all our eggs in one basket and we had a very narrow sector base, so we were really struggling in the ‘80s because we did tend to be over-reliant … We tended to be involved in these bigger heavy industries, and it really has hit us hard’ (INT5).

As such, the mid-1970s, which marked the start of deindustrialisation in many developed economies, saw peripheral places like Doncaster confronted with major structural changes as the industries which hitherto fuelled their growth started to decline. With the demand for labour reduced, deindustrialisation changed the ‘nature of the game’ for industrialised places (Byrne 2002; Lever 1991). Indeed, deindustrialisation disrupted local and regional economies, leaving many without a job, and therefore an immediate negative impact of the shock was widespread unemployment. The impact of job losses was such that, to disguise its magnitude, a high number of economically inactive men were recorded as permanently sick, essentially ‘hidden unemployment’ (Beatty et al. 2007). The shock was amplified by skills mismatches, as people faced limited options for finding employment elsewhere. The men and women working in the coalmines and factories had limited transferable skills, and therefore finding employment in other sectors which required their specific set of skills was challenging. As one stakeholder explained:

‘You then saw a huge number of what was highly skilled individuals employed in a particular industry now struggling to find work which pays the same and utilises the skills they’ve got. When having been a quite highly skilled individual down the mines, to be told ‘actually you can drive a forklift truck now’, it’s not quite the same’ (INT2).

As a result, an immediate negative impact of the job losses, which manifested at the community level, was people’s loss of confidence which affected communities’ adaptation to the shock. The stakeholders highlighted:

‘In terms of the job impact of that collapse – obviously [it was] absolutely massive. Almost the more significant thing has been the collapse in confidence in people and communities’ (INT3).

‘With the demise of all [industries] at the same time really it had quite a big impact on people’s confidence to start up in business’ (INT11).

In the 1980s, the Government changed the policy paradigm in response to deindustrialisation, promoting a rhetoric based on enterprise and ‘freedom of independent economic action’ (Dodd and Anderson 2001, p.21). However, the industrial ‘way of life’ in Doncaster and other PIPPS was characterised by employment as opposed to any entrepreneurial activity, with no discernible enterprise culture. Consequently, PPIPs became characterised by the mass employment of workers from former labour intensive manufacturing industries, as the legacy of a once thriving wage labour culture (Hudson 2005), and were slow to adapt due to the institutional imprint left by deindustrialisation., if they were able to respond at all. Despite the shift in government policy and formal institutions more broadly, Doncaster was locked in to what Byrne (2002, p.287) refers to as an ‘industrial structure of feeling’, namely the specific set of values, norms and behaviours which governed the way of life. This is akin to the cultural hysteresis described by Tubadji et al. (2016), although acutely localised in its impact as the dominant City of Sheffield was quicker to adapt to the demands of the new economy. Another consequence of mass unemployment was the limited capacity of communities to adapt to the shock, with the wage labour mentality at odds with the ideology of entrepreneurship and enterprise. Where there were examples of entrepreneurial activity they did little more than replacing the loss of a job to provide a personal income:

‘What you tended to find was that people were looking at becoming drivers, trainers, you had motoring schools and window cleaning businesses. It was quite limited. A lot of it was ‘me too’ businesses, working from home’ (INT1).

Deindustrialisation prompted the transformation of policy at the national level, and the promotion of enterprise policies in particular (Greene et al. 2004). However, the informal norms remained largely rigid in PPIPs like Doncaster. The ‘structure of feeling’ that developed around industries and underpinned their growth, particularly in peripheral places, has continued to persist. The prevailing that underpinned the growth of PPIPs for decades contrasting with the enterprise policies of central government were incongruent with the culture of PPIPs, which has subsequently resulted in uneven development and geographical disparities at both regional and intraregional levels in the UK.

4.2 Hysteresis and the institutional environment

The previous section highlighted that deindustrialisation left an institutional imprint which constrained the adaptation of the local communities to the new ideology of entrepreneurship and enterprise. However, informal institutions in PPIPs remained grounded in legacies of the past. As one stakeholder emphasised, ‘the collapse of mining … still looms large in everyone’s psyche’ (INT3). The economic decline of traditional industries has also culminated in socio-cultural decline of communities in and around Doncaster. In this way, deindustrialisation represented not only a loss of jobs, but a loss of future opportunity as communities became instituted by legacies of the past (Hudson 2005). In the absence of employment opportunities, PPIPs became characterised by what Cumbers et al. (2009) refer to in terms low levels of ambition and aspirations. In Doncaster, this was compounded by a lack of enterprise culture, with no history or tradition of self-employment. As legacies of the past continued to shape people’s perceptions of what was achievable, this culminated in economic and cultural institutional hysteresis at the local level. For example, the wage labour culture still prevails yet there is no entrepreneurial ambition:

‘Somebody grows up in the family, the family has traditionally been dependent on somebody providing a job. It’s not about training to start your own business; it’s being dependent on other people to provide businesses and jobs, often large employers. They’re no longer there but the family values have not been about developing expectations that you can start a business’ (INT7).

‘In many cases you’re looking at second, third generation unemployed. There still is, in certain communities, that mentality of ‘Well, my granddad was unemployed, my dad was unemployed, you know that’s what I’m looking to do myself’ (INT2).

As such, the impact of deindustrialisation had a disproportionate impact in PPIPs and the effects of institutional hysteresis are more acute. This has hindered the adaptation of Doncaster compared to that of the core city as described by Williams and Vorley (2014). A major factor contributing to this localised hysteresis is the loss of identity, which has a negative impact on people’s perceptions of their economic future. Indeed, deindustrialisation left many communities ‘depleted’ not only of their economic purpose but also of the identity that had originally defined them as a community:

‘For communities it was devastating in the sense that lots of places, and their raison d'être within Doncaster - because we’ve got the urban centre and then we’ve got a number of satellite villages - a lot of the raison d'être of those communities was built around traditional industries, and that raison d'être is obviously gone’ (INT12).

Thus, while the periphery has once been a primary production zone (Anderson 2000), the loss of identity and loss of economic prospects serves to reinforce negative perceptions of place devoid of economic opportunity, or at best necessity-driven entrepreneurial activity. As another stakeholder explained:

‘People feel less inclined to start-up their own business or do something that’s more outward facing. They feel that actually Doncaster’s a forgotten town. Sometimes, when you speak to many business owners, setting up a business for themselves is a last-ditch attempt to try and do something worthwhile for their family’ (INT6).

The perceived lack of opportunities relates to more than the geographical peripherality of Doncaster, but rather as Johnstone and Lionais (2004) how opportunities are socialised and understood. The periphery is, therefore, defined by social processes (i.e. the use of space within the social context), which Anderson (2000, p.93) regards as ‘culturally specific, a social construct, best explained within the interplay of culture and economics’. This mirrors the nature of institutional hysteresis found in PPIPs, where place is instituted through social reproduction. Another interviewee summed this up, stating:

‘That kind of parochiality that’s informed by the collapse of traditional industries, informed by a lack of confidence in communities and the place, it’s almost pushed and pushed and pushed Doncaster into this kind of little bubble’(INT3).

Here the implication is that Doncaster is not only peripheral but becoming further marginalised with the out-migration of the more skilled and mobile groups of the population to the other core urban centres (Kaufmann and Malul 2015). In Doncaster this has perpetuated the negative perceptions of place and perceived lack of opportunity. This weakening of the institutional environment has resulted in what the stakeholders highlight as a brain drain, with graduates and potential entrepreneurs moving away from Doncaster:

‘There’s certainly an issue that the bright young people go away to University and as we all know very few of them return back home again, so there’s certainly a drain on those resources’ (INT1).

‘They don’t see that there’s the opportunity there for them in Doncaster, so they end up looking for jobs in Sheffield or Leeds, Manchester. So the skills which we have developed locally we lose as well’ (INT2).

The brain drain is about more than the loss of human capital, as it also detracts from potential entrepreneurial activity in Doncaster, which Johnstone and Lionais (2004, p.219) regard as ‘prime agents of development’. This in turn further perpetuates and exacerbates the reproduction of local informal institutions, with deindustrialisation leaving a long-term imprint that Stuetzer et al. (2016, p.18) find to result in ‘a vicious cycle of low entrepreneurship and [a] weak entrepreneurship culture’. Moreover, where there are examples of entrepreneurial activity they tend to be highly limited in both scope and ambition. More than deindustrialisation culminating in the ‘slow burn’ in PPIPs, it sees the legacies of the past kept alive and reinforce the prevailing institutional hysteresis.

4.3 Entrepreneurship and institutional transformation

As described above, the enduring nature of informal institutions in PPIPs has hindered entrepreneurial-led renewal and growth. That said, Doncaster is not devoid of entrepreneurial activity. The continuous effort of local stakeholders to promote entrepreneurship and a culture of enterprise has resulted in an increased business start-up rate compared to other SCR localities (see Table 1). However, the nature of the entrepreneurial activity in Doncaster is both highly localised and underproductive, verging on what Viswanathan et al. (2014) refer to as ‘subsistence entrepreneurship’, and therefore has limited impact on economic growth. As one of the stakeholders interviewed highlighted:

‘There’s not the aspiration to grow those businesses into fifteen, twenty, twenty five employee businesses. There’s a kind of an acceptance that you run a business and that provides you with a living and people are content with that’ (INT7).

Audretsch et al. (2017) regard the interplay between history and culture that creates a social imprinting to determine the nature of entrepreneurial activity at the local level. Moreover, and building on the preceding discussion, Minguzzi and Passaro (2001, p.181) explain that similar social, educational and entrepreneurial experiences can lead to ‘cultural entrepreneurial homogeneity’. In the case of Doncaster, this homogeneity is reflected by the limited scope and ambition:

‘I think quite clearly the adjustments to a more of an enterprising culture, a more of a private sector, smaller business type of culture has been incredibly difficult. And I think there is a legacy of lower aspirations, lower enterprise culture’ (INT8).

‘We get a lot of enquiries from people who start a business and they tend to be people who end up a micro-business or self-employed. We get a lot of demand for that’ (INT4).

Despite changing the orientation of formal institutions, most notably in the form of national level policy to support enterprise-led growth and economic regeneration (see Huggins and Williams 2009), these have not been universally successful across regions. Indeed, the formal institutional reforms have not seen employment levels ‘bounce back’ to pre-shock levels, let alone bounce forward and see unemployment levels reduced. Several stakeholders emphasised that despite making significant investments, the nationally led policies achieved a limited impact in PPIPs as they failed to account for the heterogeneity of local level informal institutions. Thus, not only did institutional hysteresis prevail as the result of rigid informal institutions which are slow to change, an asymmetry between national formal and local informal institutions has reinforced the underlying cause of hysteresis. As a result, the approach to breaking the ‘vicious cycle’ was incomplete as despite somewhat increased levels of entrepreneurship, the scope of local entrepreneurial activity has remained limited.

Several of the interviewees referred to the limited growth potential and lifestyle nature of many businesses, with little possibility of them driving economic growth in Doncaster. This can in part be explained by Dennis’s (2011, p.96) observation regarding the ‘conflicting incentive structures’, with national level (formal) institutions promoting entrepreneurship and local level (informal) institutions ‘pulling in the opposite direction’. The interviewees did highlight that that there is a growing awareness and acceptance of entrepreneurship, although the nature of entrepreneurial activity remains inherently local and underproductive. While increasing the number of new start-ups is important as an indication of entrepreneurial activity (Ross et al. 2015), PPIPs need to ultimately foster more productive entrepreneurship. This point was mentioned by several interviewees, with one interviewee stating:

‘We need entrepreneurship, we need people to want to start businesses and grow businesses but we also want those existing businesses to grow and expand’ (INT12).

To break the ‘vicious cycle’ and promote entrepreneurship as a catalyst for economic renewal and growth Williams and Vorley (2014) have argued for a more localised approach. This is imperative if PPIPs are to overcome the challenge of institutional hysteresis, and is about more than localised policy. It is about understanding how policies and programmes relate to the prevailing informal institutions. Indeed, focusing on new start-ups can lead to stimulating the ‘wrong type’ of entrepreneurship in low enterprise areas (Mueller et al. 2008; Shane 2009; van Stel and Suddle 2008), as pursuing entrepreneurship as a way out of unemployment may inadvertently create businesses with a low probability of long-term survival and growth (Baptista et al. 2014). Therefore, while entrepreneurship policy has hitherto been devised at the national level, an important implication is that one size does not fit all (Mason et al. 2015; Ross et al. 2015). Indeed, as Tubadji et al. (2016, p.104) highlight, ‘rather complex and path-dependent cultural preference mechanisms are at stake, when pro-entrepreneurial economic policy choices are to be made’, and as institutions develop in relation to place entrepreneurship and enterprise policy must be sensitive to local institutions. Therefore a localised, ‘territorial’ and place-sensitive approach is key to fostering evidence based policy making (Arshed et al. 2014) and to enabling more productive entrepreneurship at the periphery (Baumgartner et al. 2013). As a stakeholder highlighted:

‘I think quite often we can get government initiatives that although on paper they mean well, when you actually look at the deployment across the country they sometimes don’t hit the spot, so a lot of the initiatives that might work in, say, London, are not going to work here … because they’ve not thought through what happens in different geographies’ (INT5).

Thus, by continuing to ignore the local variation of informal institutions and how rigid informal institutions can constrain entrepreneurial potential, the challenge, given the complexities of national, regional and increasingly local governance, is in ensuring that institutions evolve in a way that gives rise to (more) productive and (more) systemic entrepreneurial activity in PPIPs. That said, the tendency has been to assume a layered approach towards the evolution of institutional arrangements, and that in Doncaster the desired transformation has not occurred. However, given the complexity of governance it is not immediately possible to simply assume a recombinant approach that (re)combines the existing social-political-economic structure with new resources to produce new structures to support entrepreneurial growth. That said, while institutional hysteresis remains a challenge in terms of institutional arrangements, this is also influenced by the strategic choices of (local) actors (Christopherson et al. 2010). To this end, one interviewee stated, ‘I think our policies need to be sharper to understand Doncaster the place, understand our business community and understand where we need to take it’ (INT5). This is consistent with the call of Brooks et al. (2016, p.12) for ‘more democratic locally based strategies’, and again highlights the critical importance of local knowledge and understanding in the delivery of nationally conceived enterprise policies and programmes (Jackson et al. 2013).

5 Conclusions

This article has analysed how the local institutional environment has shaped entrepreneurship in PPIPs following deindustrialization. The key contribution of this article is to demonstrate how rigid informal institutions culminate in institutional hysteresis at the local level, and how they can be overcome to foster entrepreneurship and enhance local economic resilience in PPIPs. We highlight the major socio-economic impact of deindustrialisation which transformed into a ‘slow burn’, hindering change through institutional hysteresis. Job losses and subsequent high unemployment, a wage labour culture, the lack of entrepreneurship tradition, and the loss of identity, have contributed to institutional hysteresis at the local level. With generational unemployment and lower aspirations as legacies of the past, compounded by negative perceptions of place and opportunity, entrepreneurial ambitions remain limited. In highlighting the persistence of legacies of the past through local social reproduction, the article also contributes towards a better understanding of why some places are more resilient than others.

Through our focus on Doncaster, a post-industrial town experiencing economic underperformance which has much in common with other peripheral places, we examine how PPIPs have been acutely affected by deindustrialisation and the challenges for transforming institutions to deliver to a nationally conceived entrepreneurial and enterprise-led growth policies, thus advancing understanding in this field. Building on previous institutional and policy research, the article identifies entrepreneurship as a key process of institutional transformation in PPIPs. However, in exploring the research question, the article shows an asymmetry between national level formal institutions and local level informal institutions, with nationally conceived policy largely ignoring the heterogeneity of local institutional contexts. As such, with local level policy expected to foster more place-sensitive strategies, the implication for entrepreneurship policy is the need for a more localised approach whereby local authorities have a key role in promoting entrepreneurial-led growth. To overcome institutional hysteresis, entrepreneurship policy in PPIPs must look beyond targeting higher start-up rates, and adopt a long-term approach at targeting cultural change which is critical to fostering enterprise-led growth.

Finally, we acknowledge that the research approach used contains some limitations. The study is geographically localised given its focus on the PPIP of Doncaster and involved a relatively small number of in-depth interviews with policy stakeholders. Clearly, the views of the respondents interviewed cannot be considered to be representative of policy makers in the wider regional or national economy. While this limits the generalisability of the findings, the value of our research lies in the rich insights it provides regarding institutional hysteresis in such peripheral localities. With regards to further research, it would be worthy to investigate the extent and impact of institutional hysteresis in other peripheral locations, as well as in core economic areas to examine the transferability of national level policy to the local level. Given the differential nature of economic shocks around the world, including economic crises and natural disasters, it would also be valuable to examine how in the light of such crises policy has responded through institutional change.

References

Ache, P. (2000). Cities in old industrial regions between local innovative milieu and urban governance – reflections on city region governance. European Planning Studies, 8(6), 693–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/713666434.

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(2/3), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9.

Amoros, J. E., Felzensztein, C., & Gimmon, E. (2013). Entrepreneurial opportunities in peripheral versus core regions in Chile. Small Business Economics, 40(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9349-0.

Anderson, A. R. (2000). Paradox in the periphery: an entrepreneurial reconstruction? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 12(2), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856200283027.

Arshed, N., Carter, S., & Mason, C. (2014). The ineffectiveness of entrepreneurship policy: is policy formulation to blame? Small Business Economics, 43(3), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9554-8.

Audretsch, D.B., Obschonka, M., Gosling, S.D. & Potter, J. (2017). A new perspective on entrepreneurial regions: linking cultural identity with latent and manifest entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 48(3), 681–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9787-9.

Baptista, R., Karaöz, M., & Mendonça, K. (2014). The impact of human capital on the early success of necessity versus opportunity-based entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 831–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9502-z.

Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2014). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823.

Baumgartner, D., Pütz, M., & Seidl, I. (2013). What kind of entrepreneurship drives regional development in European non-core regions? A literature review on empirical entrepreneurship research. European Planning Studies, 21(8), 1095–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722937.

Beatty, C., Fothergill, S., & Powell, R. (2007). Twenty years on: has the economy of the UK coalfields recovered? Environment and Planning A, 39(7), 1654–1675. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38216.

Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods and Research, 10(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912418101000205.

Bristow, G. (2010). Resilient regions: re-‘place’ing regional competitiveness. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp030.

Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2014). Regional resilience: an agency perspective. Regional Studies, 48(5), 923–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.854879.

Brooks, C., Vorley, T., & Williams, N. (2016). The role of civic leadership in fostering economic resilience in City Regions. Policy Studies, 37(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2015.1103846.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burch, M, Harding, A. & Rees, J. (2009). Having it both ways: explaining the contradiction in English spatial development policy. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 22(7), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550910993362.

Byrne, D. (2002). Industrial culture in a post-industrial world: the case of the North East of England. City, 6(3), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360481022000037733.

Christopherson, S., Michie, J., & Tyler, P. (2010). Regional resilience: theoretical and empirical perspectives. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq004.

Cowell, M. M. (2013). Bounce back or move on: regional resilience and economic development planning. Cities, 30, 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.04.001.

Cross, R. (1993). On the foundation of hysteresis in economic systems. Economics and Philosophy, 9(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266267100005113.

Cross, R., McNamara, H., & Pokrovskii, A. V. (2012). Memory of recessions. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 34(3), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.2753/PKE0160-3477340302.

Cumbers, A., Helms, G. & Keenan, M. (2009). Beyond Aspiration: Young People and decent work in the de-industrialised city. Discussion Paper, University of W. Available at: eprints.gla.ac.uk /115991.

Curran, J. (2000). What is small business policy in the UK for? Evaluation and assessing small business policies. International Small Business Journal, 18(3), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242600183002.

Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2010). Towards the resilient region? Local Economy, 25(8), 650–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690942.2010.533424.

Dennis Jr., W. J. (2011). Entrepreneurship, small business and public policy levers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00316.x.

Dodd, S. D., & Anderson, A. R. (2001). Understanding the enterprise culture: paradigm, paradox and policy. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 2(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000001101298747.

Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Stephan, U. (2016). Human capital in social and commercial entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(4), 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.05.003.

Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12065.

Frank, H., & Landström, H. (2016). What makes entrepreneurship research interesting? Reflections on strategies to overcome the rigour-relevance gap. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 28(1–2), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2015.1100687.

Gardiner, B., Martin, R., Sunley, P., & Tyler, P. (2013). Spatially unbalanced growth in the British economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 13(6), 889–928. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbt003.

Greene, F. J., Mole, K. F., & Storey, D. J. (2004). Does more mean worse? Three decades of enterprise policy in the Tees Valley. Urban Studies, 41(7), 1207–1228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000214752.

Grinfeld, M., Cross, R., & Lamba, H. (2009). Hysteresis and economics – taking the economic past into account. IEEE Control Systems, 29(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCS.2008.930445.

Hall, P. (2008). A spatial typology of the emerging post-industrial geography of England and Wales. Géocarrefour, 83(2), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.4000/geocarrefour.5722.

Hassink, R. (2010). Regional resilience: a promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp033.

Hayter, R. (2004). Economic geography as dissenting institutionalism: the embeddedness, evolution and differentiation of regions. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 86(2), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00156.x.

Hudson, R. (2005). Rethinking change in old industrial regions: reflecting on the experiences of North East England. Environment and Planning A, 37(4), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1068/a36274.

Huggins, R. & Thompson, P. (2013). UK Competitiveness Index. Available at: https://www.spelthorne.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5228&p=0

Huggins, R., & Williams, N. (2009). Enterprise and public policy: a review of Labour government interventions in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(1), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0762b.

Huggins, R., & Williams, N. (2011). Entrepreneurship and regional competitiveness: the role and progression of policy. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(9/10), 907–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.577818.

Jackson, M., McInroy, N., & Nolan, A. (2013). LEPs and local government – forging a new era of progressive economic development? In M. Ward & S. Hardy (Eds.), Where next for Local Enterprise Partnerships? London: The Smith Institute, UK.

Johnstone, H., & Lionais, D. (2004). Depleted communities and community business entrepreneurship: revaluing space through place. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(3), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/0898562042000197117.

Kaufmann, D., & Malul, M. (2015). The dynamic brain drain of entrepreneurs in peripheral regions. European Planning Studies, 23(7), 1345–1356. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.929639.

Lever, W. F. (1991). Deindustrialisation and the reality of the post-industrial city. Urban Studies, 28(6), 983–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989120081161.

Martin, R. (2000). Institutional approaches in economic geography. In E. Sheppard & T. J. Barnes (Eds.), A companion to economic geography. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, UK.

Martin, R. (2010). Roepke lecture in economic geography – rethinking regional path dependence: beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x.

Martin, R. (2012). Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr019.

Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2003). Deconstructing clusters: chaotic concept or policy panacea? Journal of Economic Geography, 3(1), 5–35.

Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012.

Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2014). On the notion of regional economic resilience: conceptualization and explanation. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu015.

Mason, C., Brown, R., Hart, M., & Anyadike-Danes, M. (2015). High-growth firms, jobs and peripheral regions: the case of Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu032.

Minguzzi, A., & Passaro, R. (2001). The network of relationships between the economic environment and the entrepreneurial culture in small firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(2), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00045-2.

Mueller, P., van Stel, A., & Storey, D. J. (2008). The effects of new firm formation on regional development over time: the case of Great Britain. Small Business Economics, 30(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9056-z.

Pejovich, S. (1999). The effects of the interaction of formal and informal institutions on social stability and economic development. Journal of Markets & Morality, 2(2), 164–181.

Pendall, R., Foster, K. A., & Cowell, M. (2010). Resilience and regions: building understanding of the metaphor. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp028.

Pike, A., Dawley, S., & Tomaney, J. (2010). Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq001.

Porter, M. E. (2000). Location, competition, and economic development: local clusters in a global economy. Economic Development Quarterly, 14(1), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124240001400105.

Pugalis, L., & Townsend, A. R. (2012). Rebalancing England: sub-national development (once again) at the crossroads. Urban Research & Practice, 5(1), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2012.656461.

Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748978.

Romer, R. (2001). Advanced macroeconomics. New York: McGraw Hill.

Ross, A. G., Adams, J., & Crossan, K. (2015). Entrepreneurship and the spatial context: a panel data study into regional determinants of small growing firms in Scotland. Local Economy, 30(6), 672–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094215600135.

Salet, W., & Savini, F. (2015). The political governance of urban peripheries. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 33(3), 448–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15594052.

Schneiberg, M. (2007). What’s on the path? Path dependence, organizational diversity and the problem of institutional change in the US economy, 1900–1950. Socio-Economic Review, 5(1), 47–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwl006.

Setterfield, M. (1993). A model of institutional hysteresis. Journal of Economic Issues, 27(3), 755–774.

Setterfield, M. (2010). Hysteresis. Working Paper 10–04, Department of Economics, Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9215-5.

Silverman, D. (2000). Doing qualitative research. London: Sage.

Simmie, J., & Martin, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions: towards an evolutionary approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp029.

van Stel, A., & Suddle, K. (2008). The impact of new firm formation on regional development in the Netherlands. Small Business Economics, 30(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9054-1.

Stuetzer, M., Obschonka, M., Audretsch, D. B., Wyrwich, M., Rentfrow, P. J., Coombes, M., Shaw-Taylor, L., & Satchell, M. (2016). Industry structure, entrepreneurship, and culture: an empirical analysis using historical coal fields. European Economic Review, 86, 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.08.012.

Sztompka, P. (1996). Looking back: the year 1989 as a cultural and civilizational break. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 29(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(96)80001-8.

Thompson, J. (2010). ‘Entrepreneurship enablers’ – their unsung and unquantified role in competitiveness and regeneration. Local Economy, 25(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690940903545406.

Tubadji, A., Nijkamp, P., & Angelis, V. (2016). Cultural hysteresis, entrepreneurship and economic crisis. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9(1), 103–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsv035.

Viswanathan, M., Echambadi, R., Venugopal, S., & Sridharan, S. (2014). Subsistence entrepreneurship, value creation, and community exchange systems: a social capital explanation. Journal of Macromarketing, 34(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146714521635.

Williams, N., & Vorley, T. (2014). Economic resilience and entrepreneurship: lessons from the Sheffield City Region. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal, 26(3–4), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2014.894129.

Williams, N., & Vorley, T. (2015). Institutional asymmetry: how formal and informal institutions affect entrepreneurship in Bulgaria. International Small Business Journal, 33(8), 840–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614534280.

Williams, N., & Vorley, T. (2017). Creating institutional alignment and fostering productive entrepreneurship in new born states. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, Online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1297853.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gherhes, C., Vorley, T. & Williams, N. Entrepreneurship and local economic resilience: the impact of institutional hysteresis in peripheral places. Small Bus Econ 51, 577–590 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9946-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9946-7