Abstract

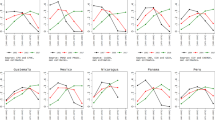

We use a decade of longitudinal data on start-ups and employment in Swedish regions to analyze the effect of start-ups on subsequent employment growth. We extend previous analyses by decomposing the effect of start-ups on total employment change into within- and cross-sector effects. We find that start-ups in a sector influence employment change in the same as well as in other sectors. The results illustrate that the known S-shaped pattern can be attributed to the different effects of start-ups in a sector on employment change in the same sector and in others. Start-ups in a sector have a positive impact on employment change in the same sector. The effects on employment change in other sectors may be negative or positive, and depend on the sector under consideration. In particular, start-ups in high-end services deviate from manufacturing and low-end services in that they have significant negative impacts on employment change in other sectors. The findings are consistent with the idea that start-ups are a vehicle for change in the composition of regional industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The role of small and new firms is maintained to be amplified by the increased pace of technological change and innovation, which shorten product cycles. Small and new firms are often maintained to have innovation and growth advantages in such contexts (cf. Acs and Audretsch 1987; Christensen and Rosenbloom 1995).

Moreover, a significant fraction of European Union (EU) funding, for instance, from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), is devoted to projects aimed at supporting start-ups in EU regions.

A special issue of Small Business Economics (2008, vol. 30) collected a number of contributions applying a similar methodology, which produced comparable results from regions in different countries. Analyses were conducted for Portugal (Baptista et al. 2008), The Netherlands (van Stel and Suddle 2008) Germany (Fritsch and Mueller 2008), the USA (Acs and Mueller 2008), Spain (Arauzo Carod et al. 2008), and Great Britain (Mueller et al. 2008). An analysis was also conducted for a set of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Carree and Thurik 2008).

Moreover, high-end services are characterized by small-scale firms among incumbents as well as entrants, which suggests that demand effects may be relatively limited.

These are the same data as Andersson and Koster (2009) make use of in their analysis of persistence in start-up rates across Swedish municipalities.

Data have been corrected for change in municipality classifications between 1994 and 2004.

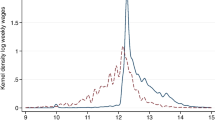

In relation to some previous Swedish analyses of start-ups and employment we employ a more precise measure of start-ups. Data on start-ups in, e.g., Nyström (2008b) is based on tracing new firm identity numbers in the business register on a year-to-year basis. In this case, firm identity may change due to changes in, for instance, legal form or simply an error. Borgman and Braunerhjelm (2007) measure entrepreneurship by the change in the number of establishments with zero or one employee.

As a robustness check we have also estimated our empirical model with start-up rates that also include start-ups with personal liability. This does not change the results we present in the sequel. Additional tables are available from the authors.

Low-end services are defined by NACE code 50–64 and include logistics and transport services, retail, wholesale, hotels, restaurants, and repair shops. High-end services are defined by NACE code 65–99 and include advanced producer services, R&D institutions, education services, etc.

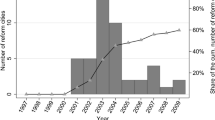

A potential explanation for the observed decline in manufacturing and low-end service start-ups since 1994 is that 1994 marked the end of a recession in the early 1990s. Improved economic conditions and a consequent recovery of the labor market in 1994 and onwards may have impeded start-up activity.

Weighted with the employment share of sector s in region r.

Weighted with the employment share of other sectors in region r.

In addition to the variables listed in the table, we have included median income in the estimations. This can be theoretically motivated but is correlated to education. When it is included in the model it has a negative parameter estimate and does not change the results presented in the sequel. Results from the estimations which include median income are available from the authors upon request.

Most studies use population per square kilometer or similar as a density measure. Our accessibility measure is also a measure of density. It combines information about the magnitude of economic activity in a municipality with information about the time distances in terms of travel by car between different zones within the municipality. In this sense it is a more precise density measure than density measures based on the geographical scope of a region (e.g., square kilometers). Actual time distances is a better description of actual interaction opportunities and proximity in a region than crude measures such as square kilometers.

As stated in the previous sections, we also tested models including start-ups with personal liability and also estimated the models with median income included among the regressors. Population density as an alternative density measures has been tested as well. The results presented here are robust to these alterations. The results with different model specifications, including polynomial lag estimates, are available from the authors upon request.

The total number of start-ups is the sum of the start-ups in low- and high-end services as well as manufacturing.

As stated previously, it is evident that the effect of total employment growth as given by the sum of the estimated parameters in column 1 (within sector) and 2 (cross sectors) is consistent with the estimated effect of high-end service start-ups on total employment change in Appendix Table 3 for all lags but t − 3. Despite the difference being statistically significant at the 10% level, it is small in magnitude.

Moreover, the measurement of start-ups applied here excludes start-ups due to splits of existing establishments.

References

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1987). Innovation, market structure and firm size. Review of Economics and Statistics, 69(4), 567–575.

Acs, Z. J., & Mueller, P. (2008). Employment effects of business dynamics: Mice, gazelles and elephants. Small Business Economics, 30, 85–100.

Albæk, K., Arai, M., Asplund, R., Barth, E., & Madsen, E. S. (1998). Measuring wage effects of plant size. Labour Economics, 5, 425–448.

Andersson, M. (2006). Co-location of manufacturing and producer services—A simultaneous equations approach. In C. Karlsson, B. Johansson, & R. R. Stough (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and dynamics in the knowledge economy (pp. 94–124). London: Routledge.

Andersson, M., & Gråsjö, U. (2009). Spatial dependence and the representation of space in empirical models. Annals of Regional Science, 43, 159–180.

Andersson, M., & Koster, S. (2009). Sources of persistence in regional start-up rates—Evidence from Sweden, CESIS Working Paper No. 177.

Andersson, Å. E., & Strömquist, U. (1988). K-Samhällets Framtid (The future of the K-society). Värnamo: Prisma.

Arauzo Carod, J. M., Solís, D. L., & Martín Bofarull, M. (2008). New business formation and employment growth: Some evidence for the spanish manufacturing industry. Small Business Economics, 30, 73–84.

Audretsch, D. B., & Fritsch, M. (1994). On the measurement of entry rates. Empirica, 21, 105–113.

Audretsch, D. B., & Fritsch, M. (2002). Growth regimes over time and space. Regional Studies, 36, 113–124.

Audretsch, D. B., & Thurik, R. (2001). What’s new about the new economy? Sources of growth in the managed and entrepreneurial economies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10, 267–315.

Baptista, R., Escária, V., & Madruga, P. (2008). Entrepreneurship, regional development and job creation: The case of Portugal. Small Business Economics, 30, 49–58.

Baptista, R., & Preto, M. T. (2010). New firm formation and employment growth: Regional and business dynamics. Small Business Economics (in this issue).

Baumol, W. J. (1967). Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth—The anatomy of urban crisis. American Economic Review, 57, 415–426.

Borgman, B., & Braunerhjelm, P. (2007). Entrepreneurship and local growth—A comparison of the US and Sweden, CESIS WP 103. Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology.

Braunerhjelm, P. (2008). Entrepreneurship, knowledge and economic growth. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 4, 451–533.

Braunerhjelm, P., & Borgman, B. (2004). Geographical concentration, entrepreneurship, and regional growth—Evidence from regional data in Sweden 1975–1999. Regional Studies, 38, 929–947.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, R. (2003). The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. In Z. J. Acs & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 437–471). Boston: Kluwer.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, R. (2008). The lag structure of the impact of business ownership on economic performance in OECD countries. Small Business Economics, 30, 101–110.

Christensen, C. M., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (1995). Explaining the attacker’s advantage: Technological paradigms, organisational dynamics, and the value network. Research Policy, 24, 233–257.

Ciccone, A., & Hall, R. E. (1996). Productivity and the density of economic activity. American Economic Review, 86, 54–70.

Czarnitzki, D., & Spielkamp, A. (2003). Business services in Germany: Bridges for innovation. The Service Industries Journal, 23(1), 1–30.

Davidsson, P., Lindmark, L., & Olofsson, C. (1994). New firm formation and regional development in Sweden. Regional Studies, 28, 395–410.

Davidsson, P., Lindmark, L., & Olofsson, C. (1998). The extent of overestimation of small firm job creation—An empirical examination of the regression bias. Regional Studies, 11, 87–100.

Davis, S., Haltiwanger, J., & Schuh, S. (1996). Job creation and job destruction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dejardin, M. (2004). Sectoral and cross-sectoral effects of retailing firm demographies. Annals of Regional Science, 38, 311–334.

Fölster, S. (2000). Do entrepreneurs create jobs? Small Business Economics, 14(2), 137–148.

Fritsch, M. (1996). Turbulence and growth in West Germany: A comparison of evidence by regions and industries. Review of Industrial Organization, 11, 231–251.

Fritsch, M. (2008). How does new business formation affect regional development? Introduction to the special issue. Small Business Economics, 30, 1–14.

Fritsch, M., & Mueller, P. (2004). Effects of new business formation on regional development over time. Regional Studies, 38, 961–975.

Fritsch, M., & Mueller, P. (2008). The effect of new business formation on regional development over time: The case of Germany. Small Business Economics, 30, 15–29.

Fritsch, M., & Noseleit, F. (2009). Investigating the anatomy of the employment effects of new business formation. Jena Economic Research Papers, 2009–001.

Fuchs, V. (1968). The service economy. New York: NBER/Columbia University Press.

Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hansen, N. (1993). Producer services, productivity and urban income. Review of Regional Studies, 3, 255–264.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2008). Gazelles as job creators—A survey and interpretation of the evidence. IFN Working Paper No. 733.

Johansson, B., Klaesson, J., & Olsson, M. (2003). Commuters’ non-linear response to time distances. Journal of Geographical Systems, 5, 315–329.

Johnson, P., & Parker, S. (1994). The interrelationships between births and deaths. Small Business Economics, 6, 283–290.

Keeble, D., Bryson, J., & Wood, P. (1991). Small firms, business service growth and regional development in the United Kingdom: Some empirical findings. Regional Studies, 25, 439–457.

Klaesson, J., & Johansson, B. (2008). Agglomeration dynamics of business services. CESIS WP 153.

Makun, P., & MacPherson, D. (1997). Externally-assisted product innovation in the manufacturing sector: The role of location, in-house R&D and outside technical support. Regional Studies, 31(7), 659–668.

Marshall, J. N., Damesick, P., & Wood, P. (1987). Understanding the location and role of producer services in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning A, 19, 575–595.

Miles, I. (2003). Services and the knowledge-based economy. In J. Tidd & F. M. Hull (Eds.), Service innovation, organizational responses to technological opportunities & market imperatives (pp. 81–112). London: Kluwer.

Miles, I., Kastrinos, N., Bilderbeek, R., & den Hertog, P. (1995). Knowledge-intensive business services—Users, carriers and sources of innovation. Manchester: PREST.

Miner, A. (1987). Idiosyncratic jobs in formalized organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 327–351.

Miner, A. (1990). Structural evolution through idiosyncratic jobs—The potential for unplanned learning. Organization Science, 1, 195–210.

Mueller, P., van Stel, A., & Storey, D. J. (2008). The effects of new firm formation on regional development over time: The case of Great Britain. Small Business Economics, 30, 59–71.

Mueller, E., & Zenker, A. (2001). Business services as actors of knowledge transformation: The role of KIBS in regional and national innovation systems. Research Policy, 30, 1501–1516.

Noyelle, T. (1982). The implications of industry restructuring for spatial organization in the United States. In F. Moulaert & P. W. Salinas (Eds.), Regional analysis and the new international division of labor. Boston: Kluwer Nijhoff.

Noyelle, T. J., & Stanback, T. M. (1984). The economic transformation of American cities. Totawa, NJ: Rowman & Allanheld.

Nyström, K. (2008a). Is entrepreneurship the salvation for enhanced economic growth? CESIS WP 143, Royal Institute of Technology.

Nyström, K. (2008b). Entry, market turbulence and industry employment growth. Empirica. doi:10.1007/s10663-008-9086-z.

Peneder, M., Kaniovsky, S., & Dachs, B. (2003). What follows tertiarisation?: Structural change and the role of knowledge-based services. The Service Industry Journal, 23, 47–66.

Persson, H. (2004). The survival and growth of new establishments in Sweden 1987–1995. Small Business Economics, 23, 423–440.

Plümper, T., & Troeger, V. (2007). Efficient estimation of time-invariant and rarely changing variables in finite sample panel analyses with unit fixed effects. Political Analysis, 15, 124–139.

Sassen, S. (2006). The global city: New York, London, Tokyo (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schettkat, R. (2007). The astonishing regularity of service employment expansion. Metroeconomica, 58, 413–435.

Schettkat, R., & Yocarini, L. (2006). The shift to services employment: A review of the literature. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 17(2), 127–147.

Schumpeter, J. (1911). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest and the business cycle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector. London: Routledge.

van Praag, M., & Versloot, P. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Business Economics, 29, 351–382.

van Stel, A., & Storey, D. (2004). The link between firm births and job creation: Is there a Upas tree effect? Regional Studies, 38, 893–909.

van Stel, A., & Suddle, K. (2008). The impact of new firm formation on regional development in the Netherlands. Small Business Economics, 30, 31–47.

Venables, A. J. (1996). Equilibrium locations of vertically linked industries. International Economic Review, 37(2), 341–360.

Weesie, J. (1999). Seemingly unrelated estimation and the cluster-adjusted sandwich estimator. Stata Technical Bulletin, 52, 34–47. (Reprinted in Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints, 9, 231–248).

Wennberg, K., & Lindqvist, G. (2008). The effects of clusters on the survival and performance of new firms. Small Business Economics. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9123-0.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for comments from Michael Fritsch, Marcus Dejardin, Kristina Nyström, and two anonymous referees that substantially improved earlier versions of this paper. We also thank Jan Andersson at Statistics Sweden for support with data issues. Martin Andersson acknowledges financial support from the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems (VINNOVA) and from the EU sixth framework program (MICRODYN project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersson, M., Noseleit, F. Start-ups and employment dynamics within and across sectors. Small Bus Econ 36, 461–483 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9252-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9252-0