Abstract

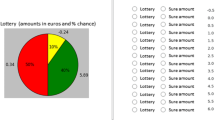

We develop a new protocol to elicit preferences over gambles that contain large, asymmetric, low-probability outcomes. Subjects first select their preferred choice from a set of zero-skewness gambles, providing a measure of their preferences for risk as standard deviation. The new lottery choices have the same expected payoffs and standard deviation as the original set of choices, but with positive skewness. We find that subjects are skewness-seekers and more importantly, positive skewness in the payoff structure increases the riskiness of subjects’ preferred lottery choices. We conclude that skewed, long-shot payoffs entice decision makers to higher levels of risk taking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

https://www.nflplayers.com/About-us/FAQs/NFL-Hopeful-FAQs/. Football is not unique. Only one major league sport (baseball) has more than 2% of NCAA players go pro (http://www.businessinsider.com.au/odds-college-athletes-become-professionals-2012-2?op=1#baseball-116-of-college-players-play-professionally-06-of-high-school-players-do-1). Though statistics are not as readily available, it is probably safe to say that similar outcomes occur in many winner-take-all professions, such as musician or actor.

Throughout this paper our concern is with positive skewness. Unless otherwise indicated, skewness should be taken to mean positive skewness.

EG is similar to Binswanger (1980, 1981), used in rural India, and is almost identical to the adaptation used in Barr and Genicot (2008) and Attanasio et al. (2012). Other studies using the EG methodology include Brañas-Garza and Rustichini (2011), Carpenter et al. (2011), Garbarino et al. (2011), Cleave et al. (2013), Reynaud and Couture (2012), Cooper and Saral (2013).

In studies which use this version, about one in five student subjects selects lottery F (see references in footnote 3).

Dave et al. (2010) compare the EG and HL protocols and find that, while the more complex HL elicitation method has superior predictive accuracy, this accuracy comes at the cost of noisier behavior, especially by low math ability subjects.

In all three studies, subjects make multiple choices between paired lotteries. A random-choice payment technique is used to determine each subject’s payoff. EW also test subjects’ taste for the related prudence. See, also, Deck and Schlesinger (2010) for tests of preferences for prudence. NTV also tests for temperance.

Both BLQ and NTV have at least one lottery pair with differing variances.

The sample was drawn from a subject pool managed by CentERdata of 9000 individuals who regularly complete internet surveys. The subsample was selected to reflect the Dutch population.

Gamble, as opposed to lottery, is the terminology used in the experimental instructions. Eckel and Grossman (2008) show no effect of framing the decision as an investment or gamble, among US students.

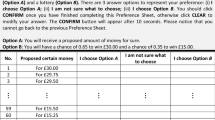

The instrument could be altered to allow for negative skewness. For example, Gamble C with skewness = −1 would be −$43.94 with p = 1%; $4.15 with p = 50%; and $25.24 with p = 49%. Given that most universities’ human subject committees would require that subjects be protected from out-of-pocket costs, such an exercise would be prohibitively costly.

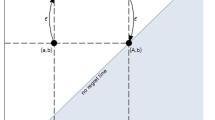

A subject who, in Task 2, selected a lottery with skewness = 1 cannot in Task 3 select a lottery with skewness = 0, unless he were to choose lottery A, the sure thing.

See the online appendix for additional examples illustrating choice sets for each task and how choices made in one task determine the choice set for the next task and the final lottery played.

To be clear, a subject would play her Task 1, zero-skewness lottery choice if in both Task 2 and Task 3 she chose to reject the higher skewness lotteries; she would play her Task 2, skewness = 1 lottery choice if in Task 2 she had chosen a Task 2, one-skewness lottery in preference to her Task 1, zero-skewness lottery choice and in Task 3 she chose to reject the higher skewness lotteries; and she would play her Task 3, skewness = 2 lottery choice if in Task 3 she had chosen a Task 3, two-skewness lottery in preference to her Task 1, zero-skewness lottery choice or her Task 2, one-skewness lottery choice.

The ROCL axiom states that the individual is indifferent between a compound lottery and the actuarially-equivalent simple lottery found by multiplying out the probabilities of the two stages of the compound lottery. For example, assume n = 2 (A1 vs. B1, and A2 vs. B2) with the lotteries defined as:

A1

(0.5 $30, 0.5 $0)

B1

(0.75 $20, 0.25 $0)

A2

(0.5 $20, 0.5 $10)

B2

(0.75 $20, 0.25 $0)

If a choice is selected at random to determine the individual’s payoff and the individual prefers Ai to Bi for all i, then, if the ROCL axiom holds, the individual should prefer A′ to B′ with A′ and B′ defined as:

A′

(0.25 $30, 0.25 $20, 0.25 $10, 0.25 $0)

B′

(0.75 $20, 0.25 $0).

We attempted to recruit a more gender-balanced sample (by holding female only sessions, etc.), but women did not volunteer as frequently as did men. When we attempted to conduct gender balanced sessions (i.e., the first 5 men and the first 5 women were seated) more men than women tended to show up. After waiting a reasonable length of time for more women to appear, the session was filled with the surplus men.

Drawn from the questions reported in Statistics Canada (2003). In 2009, the majority of the incoming class had an ACT Math score less than or equal to 23 (the 67th percentile in that year).

Subjects were not permitted to use calculators. Seven math questions were asked but the answers of one were inadvertently not recorded by the program.

SCSU has a large contingent of Nepalese students which helps to explain the high percentages of Buddhist and Hindu subjects.

Approximately 6% of our subjects select lottery F, indicating a risk loving preference. This is consistent with HL who also classify 6% of their subjects as risk loving.

Because we are interested in how the availability of skewness affects risk taking, when a subject keeps their previous-stage lottery this is coded as keeping the same lottery. For example, if in every stage 1–3 a subject selected gamble C, the independent variable measuring skewness would equal 0, 1, and 2 for stages 1, 2, and 3.

In preliminary regressions we control for age, race, relative family income, personal finances, employed (either full or part time), and their number of correct answers on the six mathematics questions. These variables are consistently insignificant and so dropped.

Complete results available upon request.

To decrease skewness, a subject has to change his/her lottery choice from a choice of lottery B–F to a choice of lottery A.

We do not control for Task. Since such a high percentage of the subjects move to a more highly skewed lottery with each opportunity, Skewness and Task are highly correlated (r = 0.91).

In preliminary regressions we control for age, race, relative family income, personal finances, employed (either full or part time), and their number of correct answers on the six mathematical questions. These variables are consistently insignificant and so dropped.

Complete results available upon request.

We tested alternative specifications such as the ratio of Maximum to Skewness but this did not alter the basic results.

In preliminary regressions we control for age, race, relative family income, personal finances, employed (either full or part time), and their number of correct answers on the six mathematical questions. These variables are consistently jointly insignificant and so dropped.

Alternatively, subjects may be using some rule of thumb that has them selecting the lottery with the highest maximum payoff.

The Powerball game’s payoff structure has also become increasingly skewed. At its outset in 1992, the odds of winning the Powerball jackpot were 1:54,979,155; today the odds of winning the Powerball jackpot are 1: 195,249,054. During this period the initial jackpot also increased from $2 million to the current $20 million. http://www.powerball.com/pb_history.asp.

Walker (2008) shows that a diversified product mix can increase aggregate sales. The 31 states and the District of Columbia listed on the Multistate Lottery Association’s website each run a minimum of three and as many as six lotto style games (http://www.musl.com/).

Since 1947, surveys consistently find that a majority of between 50% and 70% of taxpayers believe that the taxes they pay are too high (Chamberlain 2007). In contrast, there is support for lotteries: in 1984, four states held referenda on the lottery and in all cases the lottery passed overwhelmingly (Mikesell and Zorn 1986).

Clotfelter and Cook (1989) note that some states constrain the revenue raising objective in various ways (see their fn. 17).

References

Attanasio, O., Barr, A., Camilo Cardenas, J., Genicot, G., & Meghir, C. (2012). Risk pooling, risk preferences, and social networks. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4, 134–167.

Ball, S. B., Eckel, C., & Heracleous, M. (2010). Risk aversion and physical prowess: prediction, choice and bias. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 41, 167–193.

Barr, A., & Genicot, G. (2008). Risk sharing, commitment, and information: an experimental analysis. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6, 1151–1185.

Becker, G., DeGroot, M. H., & Marschak, J. (1964). Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behavioral Science, 9, 226–232.

Binswanger, H. P. (1980). Attitudes toward risk: experimental measurement in rural India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62, 395–407.

Binswanger, H. P. (1981). Attitudes toward risk: theoretical implications of an experiment in rural India. The Economic Journal, 91, 867–890.

Brañas-Garza, P., & Rustichini, A. (2011). Organizing effects of testosterone and economic behavior: not just risk taking. PLoS ONE, 6(12), e29842.

Brünner, T., Levínský, R., & Qiu, J. (2011). Preferences for skewness: evidence from a binary choice experiment. The European Journal of Finance, 17, 525–538.

Carpenter, J. P., Garcia, J. R., & Lum, J. K. (2011). Dopamine receptor genes predict risk preferences, time preferences, and related economic choices. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 42, 233–261.

Chamberlain, A. (2007). What does America think about taxes?: The 2007 annual survey of US attitudes on taxes and wealth. Washington DC: Tax Foundation.

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Imas, A. (2013). Experimental methods: eliciting risk preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 87, 43–51.

Cleave, B. L., Nikiforakis, N., & Slonim, R. (2013). Is there selection bias in laboratory experiments? The case of social and risk preferences. Experimental Economics, 16, 372–382.

Clotfelter, C. T., & Cook, P. J. (1989). Selling hope: state lotteries in america. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clotfelter, C. T., & Cook, P. J. (1990). On the economics of state lotteries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4, 105–119.

Clotfelter, C. T., & Cook, P. J. (1991). Lotteries in the real world. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 4, 227–232.

Clotfelter, C. T., Cook, P. J., Edell, J. A., & Moore, M. (1999). State lotteries at the turn of the century: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. National Gambling Impact Study Commission. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&lr=&q=cache:B4oN6hzJhz8J:www.nd.edu/~jstiver/FIN360/lottery.pdf+State+Lotteries+at+the+Turn+of+the+Century

Cooper, D. J., & Saral, K. J. (2013). Entrepreneurship and team participation: an experimental study. European Economic Review, 59, 126–140.

Dave, C., Eckel, C. C., Johnson, C., & Rojas, C. (2010). Eliciting risk preferences: when is simple better? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 41, 219–243.

Deck, C., & Schlesinger, H. (2010). Exploring higher order risk effects. Review of Economic Studies, 77, 1403–1420.

Ebert, S., & Wiesen, D. (2011). Testing for prudence and skewness-seeking. Management Science, 57, 1334–1349.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2002). Sex differences and statistical stereotyping in attitudes toward financial risk. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 281–295.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Forecasting risk attitudes: an experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 68, 1–17.

Eckel, C. C., Grossman, P. J., Johnson, C. A., de Oliveira, A. C. M., Rojas, C., & Wilson, R. (2012). School environment and risk preferences: experimental evidence. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 45(3), 265–292.

Garbarino, E., Slonim, R., & Sydnor, J. (2011). Digit ratios (2D:4D) as predictors of risky decision making for both sexes. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 42, 1–26.

Garrett, T. A., & Sobel, R. S. (1999). Gamblers favor skewness, not risk: further evidence from United States lottery games. Economic Letters, 63, 85–90.

Golec, J., & Tamarkin, M. (1998). Bettors love skewness, not risk, at the horse track. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 205–225.

Grossman, P. J. (2013). Holding fast: the persistence of gender stereotypes. Economic Inquiry, 51, 747–763.

Grossman, P. J., & Lugovskyy, O. (2011). An experimental test of the persistence of gender-based stereotypes. Economic Inquiry, 49, 598–611.

Haisley, E., Volpp, K. G., Pellathy, T., & Loewenstein, G. (2012). The impact of alternative incentive schemes on completion of health risk assessments. American Journal of Health Promotion, 26, 184–188.

Halpern, S. D., Kohn, R., Dornbrand‐Lo, A., Metkus, T., Asch, D. A., & Volpp, K. G. (2011). Lottery‐based versus fixed incentives to increase clinicians’ response to surveys. Health Services Research, 46, 1663–1674.

Hansen, A., Miyazaki, A. D., & Sprott, D. E. (2000). The tax incidence of lotteries: evidence from five states. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34, 182–203.

Harrison, G. W., Martínez-Correa, J., & Swarthout, J. T. (2015). Reduction of compound lotteries with objective probabilities: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 119, 32–55.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92, 1644–1655.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2014). Assessment and estimation of risk preferences. In M. Machina & W. K. Viscusi (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of risk and uncertainty (pp. 135–201). Oxford: North Holland.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

Kearney, M. S. (2005). State lotteries and consumer behavior. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 2269–2299.

Kimmel, S. E., Troxel, A. B., Loewenstein, G., Brensinger, C. M., Jaskowiak, J., Doshi, J. A., Laskin, M., & Volpp, K. G. (2012). Randomized trial of lottery-based incentives to improve warfarin adherence. American Heart Journal, 164, 268–274.

Mikesell, J. L., & Zorn, C. K. (1986). State lotteries as fiscal savior or fiscal fraud: a look at the evidence. Public Administration Review, 46, 311–320.

Murphy, G. M., Petitpas, A. J., & Brewer, B. W. (1996). Identity foreclosure, athletic identity, and career maturity in intercollegiate athletes. The Sports Psychologist, 10, 239–246.

Noussair, C. N., Trautmann, S. T., & van de Kuilen, G. (2014). Higher order risk attitudes, demographics, and financial decisions. Review of Economic Studies, 81, 325–355.

Reynaud, A., & Couture, S. (2012). Stability of risk preference measures: results from a field experiment on French farmers. Theory and Decision, 73(2), 203–221.

Scott, F., & Garen, J. (1993). Probability of purchase, amount of purchase, and the demographic incidence of the lottery tax. Journal of Public Economics, 54, 121–143.

Singer, J. N., & May, R. A. B. (2011). The career trajectory of a black male high school basketball player: a social reproduction perspective. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46, 299–314.

Statistics Canada & OECD. (2003). Learning a living: First results of the Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. www.oecd.org/edu/innovation-education/34867438.pdf. Accessed 7 Dec 2015.

Walker, I. (2008). How to design a lottery. In D. B. Hausch & W. T. Ziemba (Eds.), Handbook of sports and lottery markets (pp. 459–479). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Wu, C. C., Bossaerts, P., & Knutson, B. (2011). The affective impact of financial skewness on neural activity and choice. PLoS ONE, 6, e16838.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Saint Cloud State University Faculty Research Grant. Interface design and programming were conducted at the Center for Behavioral and Experimental Economic Science at the University of Texas at Dallas. We thank Thomas Sires and Sheheryar Banuri for research assistance and programming, and Mara Eckel for the interface graphic design. We also thank Glenn Harrison for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 79 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grossman, P.J., Eckel, C.C. Loving the long shot: Risk taking with skewed lotteries. J Risk Uncertain 51, 195–217 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-015-9228-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-015-9228-1