Abstract

Given the prevalence of transfer activity, education stakeholders must understand how transfer may be associated with student outcomes. Such knowledge is critical, as the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn have impacted college enrollment and student transfer behavior. Relying on a sample of 6510 undergraduate students from BPS:12/17 data, we conducted analyses using multiple regression to examine the relationship between student transfer direction and two student outcomes: time to degree and cumulative loan debt. Further, we analyzed whether these relationships varied by income status, using adjusted gross income (AGI) as a proxy. We found that transferring from one postsecondary institution to another may extend time to degree by one academic semester and result in increased student loan debt, with these findings varying by income level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

During the past few decades, college student transfer has been a prevalent practice and topic in the United States’ system of postsecondary education (Adelman, 1999; McCormick, 2003; McCormick & Carroll, 1997; Peter & Cataldi, 2005; Shapiro et al., 2018). In the 1990s, an estimated 40–50% of students attended more than one postsecondary institution, with some students transferring within the first 5 years of enrollment (McCormick & Carroll, 1997; Peter & Cataldi, 2005). More recently, 38% of students who started college in the fall of 2011 had enrolled at another institution at least once within 6 years (Shapiro et al., 2018). This rate was slightly higher for 4-year college entrants (38.5%) compared to 2-year college entrants (36.7%).

There are several types of transfers by direction (Hossler et al., 2012; Taylor & Jain, 2017). In the literature, “transfer” most often refers to vertical transfer, in which students begin at a 2-year institution and then transfer to a 4-year institution. Lateral transfer indicates transfer between institutions at the same level (i.e., between two 4-year institutions or between two 2-year institutions). Reverse transfer refers to transfer from a 4-year institution to a 2-year institution.Footnote 1 Students who reverse transfer from a 4-year college to a 2-year college may appear to be abandoning the pursuit of a bachelor’s degree, however, these students often eventually return to a 4-year school (Hossler et al., 2012). Therefore, reverse transfer can be another strategic pathway toward earning a bachelor’s degree.

Although each type of transfer direction may have varying levels of association with degree completion, other critical factors, such as income status, also contribute to college student outcomes. Depending on income and the ability to afford college, students may first decide to attend a lower-cost postsecondary institution (i.e., a 2-year institution, public institution, etc.) to complete introductory coursework and then transfer to a different postsecondary institution in hopes of completing their desired credential. This has often been motivated by the discourse on potential economic benefits such as lower student debt (Jenkins & Fink, 2015). In fact, it is estimated that more than half of all low-income students start their postsecondary education at a 2-year institution, with the goal of transferring to a 4-year institution (Berkner & Choy, 2008). The purported economic benefits of higher education (i.e., increased employability, greater lifetime earnings, etc.) are reliant upon the successful completion of a postsecondary credential, specifically an associate and/or a bachelor’s degree.

Motivated by two different ideas and messages recently put forth by policymakers and postsecondary education leaders in the higher education discourse: (1) transferring may not adversely affect total time to degree completion and (2) transferring postsecondary institutions may reduce student loan debt, the purpose of this study was to contribute new evidence on the association between college student transfer patterns on two college student outcomes, specifically time to degree completion and cumulative student loan debt. Further, we focus on how said associations differ by the income status of college students, specifically adjusted gross income (AGI). With noticeable inequalities in college student outcomes and two decades of research indicating that transferring postsecondary institutions may result in more negative outcomes than positive outcomes, it is imperative to understand and quantify the extent to which inequalities in student loan debt and time to degree vary between students from different economic levels and backgrounds. This is of particular importance as institutional mobility becomes more feasible due to the proliferation of college promise programs that provide free or low-cost 2-year educational opportunities and an increased demand for streamlined transfer pathways and credit articulation agreements.

Although many studies have examined the impact of transfer processes in the broader college cost savings and completion arena (González Canché, 2014; Hu et al., 2018; Lichtenberger & Dietrich, 2017), few studies have specifically focused on the variations in these outcomes by income level. This is critical to understand as students and families consider different pathways through college and seek to limit their associated student debt burden. In light of current transfer trends and prevalent messaging to students and their families about these decisions, the two central research questions that guided this study were:

-

(1)

Are there relationships between the direction of transfer a student makes between institutions and: (a) total time to degree in months and/or (b) cumulative student loan debt?

-

(2)

Do these relationships vary by income status when using AGI as a measure of income?

Conceptual Framework

According to Chickering and Schlossberg (2002), a transition is any event that disrupts roles, routines, and/or experiences, prompting individuals to both adapt and formulate new assumptions about themselves. Transferring universities is arguably a considerable transition that can bring myriad academic and social challenges, often leading students to change how they perceive themselves. These challenges, such as making new friends and maintaining a strong grade point average (GPA), have been well documented (Cejda, 1997; Hills, 1965; Pascarella, 1999; Rhine et al., 2000), as transfer students are frequently marginalized on their new campus (Weiss et al., 2006). Using insight from Chickering and Schlossberg (2002) on transitions, we combined three bodies of literature on the complexity of student transfer to guide this study in the development of our research questions, statistical models, and interpretation of our results. These included literature on transfer shock, transfer student adjustment, and transfer capital.

First, transfer shock refers to the initial reaction students may experience at their new institution within the first or second semester of transferring (Laanan, 2001). This shock has been commonly associated with a decline in academic performance as it pertains to student GPA and is commonly applied to community college students who transfer to 4-year postsecondary institutions. However, transfer shock could also be applied to any student who transfers, regardless of the transfer pathway, as that student must adjust to a new environment with new policies, practices, cultures, etc. Transfer shock also focuses on the emotional and psychological aspects of the transition (Chickering & Schlossberg, 2002; Laanan, 2001). That is, the potential decline in student academic performance may not be directly related to academic abilities but instead may be related to emotional and psychological processes that can ultimately affect a student’s ability to perform academically, which may extend time to degree and increase student loan debt (Hills, 1965; Laanan, 2001). Since college student transfer can be viewed as a multiphase process, we use transfer shock to emphasize the initial adjustment period for students at the receiving institution. Although transfer shock has been shown to be temporary, occurring for a short period of time immediately after transferring, it may have long-term effects on student outcomes related to time spent pursuing a degree and subsequent loan borrowing.

Second, transfer student adjustment describes a specific process along with potential challenges that students may experience when transferring from one postsecondary institution to another (Laanan, 2001). This process has been described using multiple constructs and frameworks. As it relates to the scope of this study, we incorporated definitions of transfer student adjustment as outlined by Laanan (2001), which include two key components: (1) comparisons with students at the receiving institution, and (2) personal, demographic, and environmental characteristics. These two components underscore the importance of peers (i.e., collegiality, cultural competency, etc.) and environmental factors (i.e., campus climate, academic opportunities, faculty interactions, etc.) as they relate to college student transfer. To account for personal, demographic, and environmental characteristics that coalesce to influence transfer student adjustment, we considered and included key variables in model specification during analyses.

Lastly, Transfer Student Capital (TSC) refers to the collection of knowledge that students accumulate, both before and during the transfer process, that fosters academic success and positive student outcomes (Maliszewski Lukszo & Hayes, 2020). This collection of knowledge is an amalgamation of information and resources (i.e., support and knowledge from peers and family, known academic requirements, etc.) obtained through, for example, a student’s high school experience and advisors or faculty at the sending institution. It has been emphasized that having more information and knowledge during the transfer process can help students set their expectations while creating feasible plans to successfully transition to their intended receiving postsecondary institution without encountering setbacks that may extend time to degree and/or increase costs (e.g., credit loss, unanticipated curriculum requirements at the receiving institution, etc.). The knowledge gained as part of TSC has aided in the reduction of credit loss, enhanced self-efficacy, and less turbulent transitions to new postsecondary environments (Maliszewski Lukszo & Hayes, 2020).

The convergence of transfer shock, transfer student adjustment, and TSC provides insight into why transitioning from one institution to another may extend time to degree, and in some cases lead to increased debt as a result of additional time spent pursuing a degree. By applying this conceptual framework, we may better understand how transfer, or transitioning to a new institution, is associated with time to degree attainment and cumulative loan debt, our two outcomes of interest, in addition to challenging the common conception that transferring institutions can lead to lower student loan debt. To supplement this framework, we next review the empirical literature on college student transfer and our two outcomes of interest.

Literature Review

Challenges of Transfer Students and Transfer Direction

Transferring brings a range of challenges as students adapt to their new school environment. Exploring an unfamiliar campus and learning new administrative processes (i.e., registering for classes) are necessary steps for transfer students (Townsend, 2008). Making new friends is another potentially challenging component, as previous research has documented transfer students’ difficulties making friends in an environment where most peers already have stable friendship groups (Britt & Hirt, 1999; Townsend & Wilson, 2006; Weiss et al., 2006). Such social challenges may contribute to transfer students’ inactive participation in both in- and out-of-class activities (Ishitani & McKitrich, 2010; Roberts & McNeese, 2010).

The challenges transfer students experience, however, may differ depending on the direction of transfer. An important aspect that makes transfer direction significant is differing academic environments. Particularly for students who vertically transfer (e.g., 2-year college to 4-year university), differences in academic environments between the origin and destination schools may lead to academic challenges. Prior research has reported that community college transfer students often experience a considerable decline in GPA (Cejda, 1997; Cejda & Kaylor, 1997; Hills, 1965; Pascarella, 1999; Rhine et al., 2000). Upon entering the destination university, community college transfer students may face not only higher academic standards, but also potentially different class atmospheres—less supportive and interactive instructors, more competitive peer-to-peer relationships, etc. (Davies & Casey, 1999; Laanan, 2007; Townsend, 1995, 2008). Reverse transfer students from a 4- to 2-year school have reported completely opposite experiences (Hagedorn & Castro, 1999; Townsend & Dever, 1999), confirming the existence of contrasting academic environments across institution types.

Course credit loss adds an additional practical barrier for transfer students (Contomichalos, 2014; Hodara et al., 2016; Townsend, 2008). Existing studies have estimated that, on average, about 13 credits (43% of previously accumulated credits) are lost during the transfer process (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2017) with Simone (2014) finding that 41% of transfer students move between institutions without transferring credits. To recover from credit loss, transfer students may experience longer time to degree completion and an increased financial burden due to their prolonged enrollment. Monaghan and Attewell (2015) even argued that credit loss functions as a critical mechanism that places community college transfer students at a disadvantage in completing their degrees. In their analysis, transfer students who had most of their credits accepted had 2.5 times greater odds of completing their degrees within 6 years of matriculation than those who had lost more than half of their credits in the transfer process. Another study confirmed the significance of credit loss on the graduation rate of transfer students, where differences in the 6-year graduation rate between transfer students (from both 2- and 4-year institutions) and native students were significant only when fewer than 33 credits had been accepted during transfer (Gao et al., 2002).

However, how many credits are lost in the transfer process often depends on the direction of transfer. According to existing studies using nationally representative data on college students, in general, higher percentages of course credits are accepted during transfers from 2-year colleges to 4-year universities or between two 4-year universities than during transfers from 4-year universities to 2-year colleges or between two 2-year colleges (Simone, 2014; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2017). Specifically, students transferring to 4-year institutions lost 9–10.6 credits on average, whereas students who transferred to 2-year institutions lost about 17.3–18.3 credits. Moreover, 12–17% of students transferring to 4-year universities lost all accumulated credits, compared to about half of students transferring to 2-year schools (Simone, 2014). Such differences suggest a possible structural disparity in student outcomes related to the direction of transfer.

Student Outcomes

It is believed that transferring, specifically transferring from a community college to a 4-year institution, has potential positive benefits (i.e., lower total costs of tuition and fees in pursuit of the desired degree), although this is highly debated in higher education. Further, there are many concerning negative outcomes associated with transferring to different postsecondary institutions (i.e., dropout, credit loss, decline in GPA, etc.).

Time to Degree

The literature, mainly focusing on vertical transfers from 2- to 4-year institutions, has presented mixed findings on the role of transfers on degree completion. A group of studies reported no significant difference in graduation rates between community college transfer students and native students (Anglin et al., 1995; Jones & Lee, 1992; Melguizo et al., 2011). In contrast, other studies demonstrated disadvantages with starting at community colleges (Doyle, 2009; Hu et al., 2018; Jenkins & Fink, 2016; Long & Kurlaender, 2009; Monaghan & Attewell, 2015). The inconsistent findings in the literature might be attributed to differences in the methods applied, and more specifically to whether and how the researchers controlled for possible selection bias. Furthermore, the role of transfer may reach beyond degree attainment outcomes. For example, Lichtenberger and Dietrich (2017) tracked 7 years after initial enrollment to investigate if starting at a community college penalized students in terms of time to degree. While initial graduation rates appeared to be higher among native students compared to transfer students, that gap disappeared five years after matriculation. That is, transferring may lengthen time to degree, thereby increasing students’ opportunity costs and borrowing burdens.

The positive relationship between the number of institutions attended on time to degree has been well-documented, indirectly suggesting that the number of transfers, regardless of direction, is associated with longer time to degree completion (Bradburn et al., 2003; Hossler et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2016). Previous empirical studies, however, have mostly investigated the role of vertical transfers on time to degree, presenting different findings on how much time on average, if any, a transfer student may expect to spend in pursuit of a postsecondary degree (Bound et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2018; Long & Kurlaender, 2009).

Examining the relationship between student transfer and baccalaureate (BA) degree completion for two cohorts of students from 1972 and 1988, Bound et al. (2012) showed that students who began at community colleges and less-selective universities experienced increased time to degree completion after successfully transferring, with fewer than 16% of students successfully completing a BA degree within 4 years and the majority of students taking 5 years to attain a degree. In another study, Long and Kurlaender (2009) confirmed those results, finding that students who began at community colleges and successfully attained a bachelor’s degree after transferring were more likely to complete the 4-year degree in 6 years. In some cases, students took as long as 9 years to complete a 4-year degree, though the authors posit this could be due to many additional factors such as attendance intensity (i.e., beginning college on a part-time basis). Hu et al. (2018), using a cohort of students who began college in 2004, estimated that community college transfer students took between 2.4 and 5.1 additional months to attain a bachelor’s degree, with the average completer taking about 3 months longer to complete the degree than their counterparts who started at 4-year institutions.

While these studies have provided evidence on the relationship between college student transfer and time to degree over the past 40 years, they only accounted for vertical transfers from a 2- to a 4-year postsecondary institution and did not account for other types of transfer patterns such as lateral and reverse transfers. Likewise, gaps remain in the literature as it pertains to the relationship between transfer students’ income levels and their subsequent time to degree outcomes and student loan borrowing. For example, Goldrick-Rab et al. (2016) examined income inequality in educational attainment by estimating the impact of a private need-based grant program on college persistence and degree completion using factors such as AGI and standardized test scores. Although the researchers accounted for income and/or socioeconomic status in their analyses to estimate time to degree, their study did not make direct comparisons between income levels. By not making direct comparisons by income levels, nuances related to how a student’s financial status may be associated with their ability to graduate on-time could be overlooked.

Cumulative Student Loan Debt

With findings indicating transfer students may experience extended time to degree completion by at least one academic semester, it is important to understand how student debt may increase as a result of additional enrollment. Empirical evidence has demonstrated the relationship between time to degree completion and the amount of loan debt students incur (Harrast, 2004; Witteveen & Attewell, 2019). Although student loans are not new forms of financing education, the increasing debt burden on students to cover the costs associated with college is of great concern in higher education (e.g., Fox et al., 2017; Gervais & Ziebarth, 2019; Herzog, 2018).

Similar to the body of studies regarding time to degree, findings on cumulative loan debt for transfer students have been somewhat inconsistent. In addition to examining time to degree, Hu et al. (2018) found lower cumulative loan debt for students who began at community colleges (a difference in cumulative loan debt of $2221), possibly due to lower tuition and fees at their first institution of attendance. For those who attained bachelor’s degrees, Hu et al. (2018) noted that extended time to degree may mitigate initial cost savings. While they found potential lower loan debt for transfer students who began at less expensive institutions, they did not directly explore if results varied by income level. Instead, they accounted for key components of socioeconomic status (i.e., parents’ education level, family incomes, and expected family contributions). Focusing his attention on the potential cost savings associated with starting at a community college and then transferring to a 4-year institution, González Canché (2014) concluded that students who began at community colleges did not fare any better or worse than students who began at 4-year institutions in terms of loan debt. These findings were presented after accounting for attendance intensity, credits attempted/earned, co-enrollment, and time to degree, indicating the perceived benefits of lower tuition and fees due to entering a lower-cost 2-year institution may be diminished by other factors. Like many studies on student transfer, these studies on debt accumulation for transfer students have primarily focused on students who pursued vertical transfers.

Several studies that examined student loan debt also included variables to examine the relationship between student loan behavior and other student characteristics. For example, in a study that examined the behaviors of student loan borrowers, Barr et al. (2016) used several control variables such as AGI, race, gender, and dependency status for financial aid to determine whether their treatment would have impacted students’ borrowing behavior. In a similar study, Kantrowitz (2009) reported that the number of college students graduating with debt has continued to grow and that such trends persisted even when controlling for differences in AGI or Pell Grant recipient status.

Flint (1997) investigated repayment behaviors of students using the Student Loan Recipient Survey (SLRS) of the 1987 National Postsecondary Study Aid Study (NPSAS:87). Specifically, the author modeled the prediction of loan default status as default or repayment using student background variables (i.e., gender, race, age, parents’ education, family income), institutional choice characteristics (i.e., highest degree, sector, church-related, admission selectivity, enrollment), student academic variables (i.e., status of index major, cumulative GPA, total terms enrolled, earned credential), loan counseling characteristics (i.e., source of loan, aid packages, amount borrowed, number of loans, number of lenders), exit counseling characteristics (i.e., counseling source by timing, extent paid by others, number of others), and other variables (i.e., disposable income, congruence, future aspiration, marital status, number of dependents). Among those variables, gender, race, age, cumulative GPA, source of loan, number of lenders, counseling source, disposable income, and congruence were found to be statistically significant in the model.

Although the vertical transfer pathway is most common, only focusing on this transfer pathway neglects the trends and outcomes of students who pursued other transfer pathways (i.e., lateral or reverse), as these pathways may be selected in hopes of attaining a degree and/or reducing costs associated with attending college. Just as many students choose vertical transfer pathways for financial reasons, reverse transfer pathways can also be often financially motivated (Hagedorn & Castro, 1999). Meanwhile, the convenience of location is another important reason for lateral transfers (Taylor & Jain, 2017). However, how different transfer strategies may affect students’ financial burdens and debt levels has been understudied. The present study addressed these gaps by examining the relationships between college student transfer patterns on two outcomes of interest, time to degree and cumulative loan debt.

Method

Dataset and Measures

The participants selected for this study were students from the restricted-use Beginning Postsecondary Students 2012/2017 (BPS:12/17) survey conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) at the U.S. Department of Education. BPS:12/17 is the third and latest completed study in the BPS program and followed a cohort of students enrolled in their first year of postsecondary education. This dataset measured student persistence and postsecondary education completion including employment transition and demographic characteristics (Bryan et al., 2019). Data were collected using a two-stage sample design where postsecondary institutions were selected followed by the selection of students from those institutions. Participants in BPS:12/17 were originally surveyed at the end of their first academic year in 2011–2012, and then were invited to follow-up at the end of their third (2013–2014) and sixth years (2016–2017).

For the current study, only students who attained a bachelor’s degree were included, as students who did not complete their degree may be systematically different from those who did especially in terms of the outcomes variables of months enrolled and cumulative loan debt (Bryan et al., 2019). Further, students who reported having an undecided major at the time of graduation were excluded since it is highly uncommon for students to successfully attain a bachelor’s degree without declaring a major. The final analytic sample consisted of 6510 students representing a weighted sample of 1.53 million students (or approximately 37% of the sample).

Although we only included students who graduated with a bachelor’s degree, as done in similar studies using BPS (see Jackson & Reynolds, 2013), and we are not claiming to have causal estimates, we recognize there may be selection bias in our estimates. However, since we used a pre-collected nationally representative dataset, it was not possible to randomly assign participants. We recognize that popular alternatives include quasi-experimental methods, such as propensity score matching, however, there are still flaws with this type of design (see King & Nielsen, 2019). Further, research has demonstrated an association between student loan debt and college completion or persistence (Attewell et al., 2011; DesJardins et al., 2002). Since our variables of interest included student loan debt and transfer, we wanted to ensure our sample shared the similarity of obtaining a bachelor’s degree.

Dependent Variables

The first dependent variable was cumulative loan debt, which accounted for cumulative student loan amounts borrowed through 2017. These data were collected from the BPS:12/17 Interview, the National Student Loan Data System (NSLDS:14; NSLDS:12), and the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:12 Student Records). The second dependent variable of interest was months enrolled, which accounted for the total number of months the student was enrolled at any institution through June 2017. These data were collected from the BPS:12/17 Interview, the BPS:12/14 Interview, the BPS:12/17 Student Records, the NPSAS:12 Student Records, the National Safety Council (NSC), and the NSLDS:17.

Independent Variables

The primary independent variables of interest included transfer direction for those who successfully transferred from one institution to another and AGI. Transfer direction was classified as the student’s first transfer or when the student left one institution and enrolled at another for four or more consecutive months. This variable was categorized as never transferred (i.e., student never left their first institution), vertical transfer (i.e., student transferred from a 2- to 4-year institution), and lateral transfer (i.e., the student transferred from a 2- to a 4-year institution or a 4-year to a 4-year institution). The AGI variable measured the income of students during the first year of college (2011–2012). For students who identified as a dependent, their parent/guardian AGI was used, and for students who identified as independent, AGI from the student and, if applicable, their spouse/partner was used. AGI was selected as it is typically less flawed than variables like Pell Grant status and has been commonly used in previous research (Delisle, 2017; Goldrick-Rab et al., 2016; Kantrowitz, 2009). Data for these variables were collected from the BPS:12/17 Interview, the BPS:12/14 Interview, the NPSAS:12 Interview, the NSC, the NPSAS:12 Student Records, the NSLDS:17, the BPS:12/17 Student Records, and the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS:11).

Control Variables

In addition to our dependent and independent variables, we included control variables to better understand the relationships between college student transfer and the primary outcomes of interest. The control variables were selected based on results and findings from previous research that highlighted factors that may be associated with college student outcomes and transfer patterns. Control variables can be categorized into two classification groups: (1) individual characteristics and (2) postsecondary characteristics. Variables considered as individual characteristics were gender, race, parents’ education, immigrant generation status, dependency status, risk status index (i.e., a variable that summed seven characteristics that may be adversely associated with persistence and attainment in college), and disability status (Burgstahler et al., 2001; Dennis et al., 2008; González Canché, 2014; Laanan et al., 2010; Wawrzynski & Sedlacek, 2003). Individual characteristics also included variables that measured pre-college academic factors such as high school GPA and participation in college-level coursework in high school (Spencer, 2019). Variables included as postsecondary characteristics were the level of first institution, institutional type, attendance intensity (i.e., full-time, part-time, etc.), and college major (Bailey et al., 2005; Laanan et al., 2010; Townsend & Wilson, 2006). Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for all variables analyzed.

Analyses

Descriptive Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to identify patterns in the data and determine whether assumptions were met for the regression analyses (i.e., data screening, lack of outliers, checks for normal distributions). Continuous variables were reported using means and standard deviations and categorical data were reported using frequencies and percentages.

Regression Analyses

To determine the associations between our variables of interest on our multiple outcome variables, multiple regression was implemented. Due to variables being measured on different scales, all continuous variables in the model were standardized (M = 0, SD = 1) to create standardized regression coefficients for the continuous variables and effect size measures for binary variables. To interpret comparisons between dummy coded variables (i.e., gender, race, etc.), Cohen’s d (1992) was used (0.20 = small, 0.50 = moderate, and 0.80 = large). In addition, survey weights were normalized by taking the raw weight and dividing it by the mean of the weights (Hahs-Vaughn, 2005). College/university fixed effects were included in the models by dummy coding the school identification variable (Huang, 2016). To answer the research questions, four regression models were developed:

1a. Student characteristics model on months enrolled (e.g., student gender; student race; parental education level; level of first institution; type of first institution; immigrant generation status; dependency status; whether taken college classes in high school; student attendance, either full-, part-time, or mixed; disability status; college major; direction of first transfer; high school GPA; risk status index; AGI; and cumulative loan debt);

1b. Interaction model on months enrolled (e.g., all characteristics from Model 1a, in addition to the interactions between transfer direction and AGI);

2a. Student characteristics model on cumulative loan debt (e.g., includes the same variables as Model 1a, except the outcome variable is cumulative loan debt and months enrolled is a predictor variable);

2b. Interaction model on cumulative loan debt (e.g., all characteristics from Model 2a, in addition to interactions between transfer direction and AGI).

Due to missing data, multiple imputations were completed. This method is recommended as it accurately estimates variability and standard error estimates (Dong & Peng, 2013). After investigating the patterns of missingness, data were missing at random, suggesting that multiple imputations were an appropriate procedure (Austin et al., 2021). Using guidelines suggested by Allison (2001) and Bodner (2008), 17 datasets were imputed since 17% of the data were missing. The MICE (multivariate imputation by chained equations) package (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoom, 2011) in R 3.3 (R Core Team, 2016) was used to impute the data. Results were pooled using Rubin’s (1987) rules.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, these data were from a secondary dataset that was comprised of students who voluntarily opted into the original BPS:12/17 study and participated in the survey for a 6-year period. Therefore, the BPS dataset may consist of a set of students who are particularly interested in policies and protocols compared to students who opted out of the study or began the study but did not fully participate in all three benchmarks during the 6-year period. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to different types of students who may not have had access to participate in the original BPS:12/17 study and/or students who transferred during college and ultimately earned a postsecondary credential but are not represented in the dataset. Additionally, we acknowledge the disproportionate racial representation within our sample as compared to national enrollment trends for the 2011 to 2017 time period. Nationally, white students made up 52% of undergraduate college student enrollment while Black students made up 13%, Hispanic students made up 21%, Asian students made up 7%, and other racial groups combined made up 8% (Hussar et al., 2020), whereas our sample was 69% white, 8% Black, 12% Hispanic, 7% Asian, and 4% Other. The overrepresentation of white students and underrepresentation of Black, Hispanic, and Other students in our sample may be due to participant recruitment in the original BPS study from which the sample is derived. While BPS has improved in racial representation since its first cohort in the 1990s, more consideration around race should be given when recruiting students for participation. In light of these limitations, individuals should exercise some caution when considering differences between critical populations as they pertain to race, the ability to participate in BPS, and/or transfer status. We also recognize there may be selection bias in our estimates. Extant literature has noted students who transfer may be inherently different across multiple variables and factors than students who do not transfer (McGuire & Belcheir, 2013; Xu et al., 2018a, 2018b), which may further explain time to degree and cumulative loan debt in a more nuanced way. The inability to control for all variables measuring the difference between students who transfer and those who do not may likely bias estimates in favor of those do transfer. Considering the differences that exist between students who transfer and those who do not might exert notable influence on the two outcomes of interest, the results of the study should be interpreted with care when implementing policies, resources, services, and/or providing guidance to directly address outcomes of students who may aspire to transfer during college. Future research might consider employing quasi-experimental quantitative approaches to reduce bias when drawing comparisons between groups.

Results

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between college student transfer patterns and two outcomes of interest: time to degree and cumulative loan debt. We reported our results by discussing the estimates produced from our multiple regression analyses and the interactions of interest. Four regression models with imputed data were used to investigate the relationship between AGI and transfer direction on two distinct variables: months enrolled and cumulative loan debt, respectively. In Model 1a, when months enrolled was the outcome variable, students who laterally transferred (B = 5.18, p < .001) were more likely to enroll in college longer than students who did not transfer. Further, for every one standard deviation increase in AGI, months enrolled decreased by 0.02 standard deviations, p < .001 (Table 2).

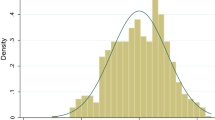

Model 1b investigated the interaction between transfer direction and AGI on months enrolled (see Fig. 1). There was a statistically significant interaction between AGI and vertical transfer (B = 0.11, p < .01). To better understand this interaction, simple slopes analysis was conducted (Hayes & Montoya, 2017). For students who completed a vertical transfer compared to not transferring, the interaction was statistically significant for levels above 0 standard deviations. The effect size for this interaction was large, ranging from 0.17 (at 0 SDs) to 0.80 (at 5 SDs). Lateral transfer was not statistically significant.

Source U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study 2012–2017 (BPS:12/17)

Interaction between transfer direction and adjusted gross income on months enrolled. Note lateral transfer was not shown because it was not statistically significant.

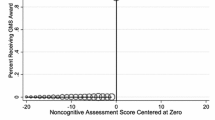

In Model 2a, transfer direction and AGI were statistically significant predictors of cumulative loan debt, p < .05. Specifically, students who laterally transferred had lower cumulative loan debt than students who did not transfer (B = − 0.10, p < .001) and students with higher AGI had lower cumulative loan debt (B = − 0.06, p < .001). Model 2b investigated the interaction between transfer direction and AGI on cumulative loan debt (see Fig. 2). This interaction was statistically significant and probed using simple slopes analysis (Hayes & Montoya, 2017). For students who completed a vertical transfer compared to students who did not transfer, the interaction was statistically significant for levels above 1 standard deviation. The effect size was moderate, ranging from .11 (at 1 SDs) to .57 (at 5 SDs). Lateral transfer was again not statistically significant.

Source U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study 2012–2017 (BPS:12/17)

Interaction between transfer direction and adjusted gross income on cumulative loan debt. Note lateral transfer was not shown because it was not statistically significant.

Discussion and Implications

This study was conceived and implemented considering the noticeable trends of college transfer patterns and public messaging that enrolling first in a lower-cost institution and subsequently transferring may facilitate greater efficiency in attaining a bachelor’s degree in terms of time spent and accumulated debt. With this study, we aimed to provide new evidence on the relationship between income status, transfer patterns, and two specific outcomes for bachelor’s degree recipients: months to degree completion and cumulative student loan debt. Critical to the current project is the recognition that the study of transfer student outcomes inherently involves examining questions of equity and inclusion in higher education. Patterns in the literature have shown how income is associated with students’ enrollment behavior and transfer activity. While students can and do transfer in vertical, lateral, or reverse directions, vertical transfer from a 2- to a 4-year institution remains the predominant pathway. This study provides a valuable update and extension of existent literature on transfer students with two key findings.

Finding 1: Transferring May Not Reduce Time to Degree

The finding that students who transferred, be it vertical or lateral, were more likely to remain enrolled for a longer period than those who did not transfer supports previous research on the various challenges associated with transfer students’ timely progression toward a degree (Cejda, 1997; Hills, 1965; Laanan, 2001; Weiss et al., 2006). It is also likely that the transfer students in our sample experienced some level of credit loss or credit duplication in their movement between institutions that necessitated a longer period of enrollment than students who entered and completed their degree from one institution (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2017).

Additionally, we found a significant interaction between the direction of transfer and AGI on the number of months students were enrolled. Specifically, the number of months enrolled increased as AGI increased for both vertical and lateral transfer students, while months enrolled decreased for each standard deviation increase in AGI for students who never transferred. Students whose first transfer was lateral spent the greatest number of months enrolled; given that the students in our sample all completed a bachelor’s degree, this indicates that transferring between institutions that are similar in level continues to pose barriers and challenges, which further underscores potential hurdles highlighted by theories on transition and TSC (Chickering & Schlossberg, 2002; Laanan, 2001). In addition to spending more time enrolled than their peers whose initial transfer was vertical, we saw that income may mitigate excessive additional months enrolled when included as an interaction. As AGI increased, the gap in months enrolled prior to bachelor’s degree completion increased at a steeper rate for students who vertically transferred compared to those who never transferred or transferred laterally. While these findings indicate that lower-income students completed their degrees more quickly, it also opens a window of critical inquiry into the circumstances that may contribute to higher-income students remaining enrolled for longer periods.

Sixty-five percent of students in our sample began their postsecondary education at a public institution; for 2-year entrants, this is likely a public community college. Vertical transfer students from higher-income backgrounds may be more likely than those from lower-income backgrounds to subsequently transfer into a private 4-year institution in pursuit of their bachelor’s degree. Not only do private institutions typically charge higher tuition rates than public institutions—creating a financial barrier to access for lower-income transfer students—but critically, credit articulation agreements are less likely to exist between a public 2-year and private 4-year institution than between public 2-year and public 4-year institutions in the same state (Jenkins & Fink, 2015). Prior studies have shown that students transferring into a private non-profit institution transferred more than 20% fewer credits (and those who transferred into a private for-profit college transferred more than 52% fewer credits) than those who transferred into a public institution (Simone, 2014). Accordingly, lower-income students transferring between public institutions may need to recoup fewer credits to complete a bachelor’s degree compared to higher-income students transferring to a private institution.

Further, students with higher incomes may have benefited from having greater financial resources and/or personal supports that allowed them to afford extending their enrollment period. For example, these students may have had the financial capacity to change majors, explore different courses of study, or participate in study abroad programs, internships, or co-op learning experiences. Comparatively, those transfer students from lower-income backgrounds may have experienced internal and/or external pressures to complete their degrees faster, potentially limiting their ability to explore different fields of study than their initial major or contributing to inequities in access to academic and co-curricular opportunities during their enrollment.

Finding 2: Transferring May Be More Expensive in the Long Run

The current study also examined cumulative loan debt taken on by bachelor’s degree-completing transfer students. Given the prior findings on time to degree following transfer and the demonstrated likelihood of transfer students experiencing some level of loss of accumulated academic credit, it follows that transfer students may need to take on larger amounts of student debt to finance their enrollment, which corroborates the existing literature on potential academic and financial pitfalls of transferring postsecondary institutions (González Canché, 2014). Our results illustrate that transfer direction and income can be best understood collectively as opposed to separately. When examining the interactions between transfer direction and income, the results showed that students who transferred vertically had higher student loan debt than students who never transferred. Moreover, the results highlighted that higher-income vertical transfer students held more debt than lower-income vertical transfer students. One interesting result of our study that supports the notion of possible debt reduction as a result of transferring noted lateral transfers resulted in lower cumulative loan debt when not accounting for income. This could be better understood within future research investigating the differences in cost of attendance between the sending institution and receiving institution as there may be cases when the two institutions vary by control (e.g., beginning at a 4-year private institution and then transferring to 4-year public institution).

As both prior research on transfer (including the persistent focus in the literature on the vertical transfer pathway) and patterns of institutional practice reflect, 2-year institutions have traditionally been thought of as the entities primarily responsible for preparing students for transfer to a 4-year institution (Xu et al., 2018a, 2018b). If transfer students were unsuccessful in their application and transition to a 4-year university or did not go on to complete a bachelor’s degree, those expectations could result in ascribing fault to the 2-year school for inadequate preparation, or alternatively to the students themselves for personal lack of persistence or ability. Yet it is now broadly recognized that such expectations give insufficient consideration to the vital role that receiving institutions (often 4-year universities) play in ensuring a smooth transition. Further, both 2- and 4-year institutions must be actively engaged in collaborative efforts to support students along the transfer pipeline and establish practices and policies to promote transfer student success (Xu et al., 2018a, 2018b). With both the costs of attending college and outstanding national student debt steadily increasing, particularly for borrowers of color (Chan et al., 2019; Houle & Addo, 2019; Kim et al., 2017), the current study’s examination of factors associated with transfer students’ timely degree completion and cumulative borrowing offers a warranted addition to the growing body of research informing transfer pathways and policies.

Implications

The results presented in this study have important implications for postsecondary education in the United States in the realms of both research and policy. In the research arena, a consistent effort to understand transfer student outcomes by student characteristics and student enrollment trends is imperative. While prior research has shown that transfer activity can be a negative predictor of degree attainment (Fauria & Slate, 2014; Handel & Williams, 2012; Jenkins & Fink, 2015), limiting the dataset to students who attained a bachelor’s degree allows the current study to examine how the circumstances of transfer are associated with time to degree and cumulative debt load for a population of students who completed their desired credential, and to deepen our understanding of how those differences may vary by students’ income. Research must continue to examine how transfer activity and patterns may be associated with persistence and degree attainment, especially given (1) enrollment trends for traditionally underserved students (i.e., racially under-represented and low-income students) and (2) the likelihood of consistent, if not increased, transfer rates for students as a result of COVID-19 altering enrollment behavior and the proliferation of college promise programs across many states. Over half of students with incomes of less than $30,000 who entered college for the first time in 2011 enrolled in a 2-year institution; and in Fall 2020, community college students represented 53% of Native American undergraduates, 50% of Hispanic undergraduates, 40% of Black undergraduates, and 36% of Asian/Pacific Islander undergraduates nationally (American Association of Community Colleges, 2022).

Historically underrepresented in higher education, students of color and students from low-income backgrounds represent a plurality of the pool of potential vertical transfer students. Supporting these student populations through the transfer pipeline to degree completion has significant equity implications for individual students and families and for state and national educational attainment goals. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has both laid bare the deeply entrenched inequities in the US higher education system and created valid cause for concern that the progress that has been made in closing equity and attainment gaps may be halted—or even reversed—in the years ahead. The myriad pressures placed on students and families by the pandemic and economic downturn may also contribute to an uptick in student transfer between institutions by leading students to consider, for example, college options that are lower-cost or closer to home (Fishman & Hiler, 2020). This will be of great importance as postsecondary education stakeholders strive for greater equity across the system.

In the policy arena, more and stronger memorandums of understanding (MOUs), credit articulation agreements, and student-facing transfer planning guides and advisory supports are needed. As of 2020, over 30 states had enacted policies to ensure statewide guaranteed transfer of 2-year associate degrees and require that lower-division general education credits be transferable across public institutions (Francies & Anderson, 2020). Key policies and frameworks that promote strategic transfer readiness at the institutional and state levels, such as the establishment of articulation agreements to facilitate smoother transfer of credit and transparency mandates that ensure clear, relevant information on transfer pathways and processes is readily available to students, should be required and updated frequently. Given that many students attend postsecondary institutions in more than one state while in pursuit of a degree, greater interstate collaboration and innovative partnerships are long overdue and will be needed in the decades to come.

Incentivizing the development and implementation of transfer partnerships that apply to all public institutions within a state would be highly beneficial in supporting transfer students—particularly given the notable proliferation of tuition-free community college promise programs in many states. The availability of these programs is likely to increase interest and enrollment in public 2-year institutions, necessitating sustained policy focus on strengthening transfer pathways if states wish to ensure that the growing number of students pursuing an associate degree through such programs will have clear and viable opportunities to transfer and attain a bachelor’s degree without experiencing significant credit loss, delayed time to degree, or unwieldy student debt.

Conclusion

In today’s postsecondary education system, with students eager to enter the US labor market on a full-time basis and families becoming increasingly interested in reducing financial burdens as they relate to college, this quantitative study contributes to research and the conversation within the postsecondary education context by encouraging leaders and individuals working with transfer students to critically think about outcomes for students who transfer postsecondary institutions. With the intent to examine and highlight the nuanced relationship between transferring postsecondary institutions and outcomes for students who attained a bachelor’s degree, the findings from this study confirm that college student transfer may not reduce student debt and/or time to degree for all students across different income levels.

As such, policymakers and leaders engaged in messaging that suggests students should consider transferring postsecondary institutions as a method for making postsecondary education more efficient and affordable for students might reframe their messaging to reflect the nuances of the transfer process and be more transparent that this approach to postsecondary education may not prove beneficial to all students who pursue these pathways. Using secondary data from the National Center for Education Statistics, we underscore that cumulative loan debt and time to degree in terms of months is comparatively greater for high-income students than low-income students. College student transfer theories (i.e., transfer shock, transfer student adjustment, TSC, etc.) served as a framework to better understand why transfer status and transfer pathways may yield varying results for students enrolled in postsecondary education in the United States.

Data availability

This study used restricted-use dataset provided by the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). The restricted-use BPS:12/17 dataset may be accessed by securing a Restricted-use Data License.

Notes

The term “reverse transfer” is also used to refer to the process of retroactively awarding an earned associate degree to a student who transferred from a two-year institution to a 4-year institution and fulfilled the requirements for the associate degree at the 4-year institution. See, e.g., Anderson, L. (2015). Reverse Transfer: The path less traveled. Education Commission of the States, www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/01/18/77/11877.pdf. For the purposes of this paper, we operationalize the definition of “reverse transfer” to mean the direction of transfer from a 4-year institution to a 2-year institution.

References

Adelman, C. (1999). Answers in the toolbox: Academic intensity, attendance patterns, and bachelor’s degree attainment. U.S. Department of Education.

Allison, P. (2001). Missing data (SAGE University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, series no. 07-136). SAGE.

American Association of Community Colleges. (2022, February). Fast Facts 2022. American Association of Community Colleges. https://www.aacc.nche.edu/research-trends/fast-facts/, https://www.aacc.nche.edu/research-trends/fast-facts/

Anglin, L. W., Davis, J. W., & Mooradian, P. W. (1995). Do transfer students graduate? A comparative study of transfer students and native university students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 19(4), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066892950190404

Attewell, P., Heil, S., & Reisel, L. (2011). Completing explanations of undergraduate noncompletion. American Educational Research Journal, 48, 536–559. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210392018

Austin, P. C., White, I. R., Lee, D. S., & van Buuren, S. (2021). Missing data in clinical research: A tutorial on multiple imputation. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 37(9), 1322–1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2020.11.010

Bailey, T. R., Calcagno, J. C., Jenkins, D., Kienzl, G. S., & Leinbach, T. (2005). The effects of institutional factors on the success of community college students. Columbia University.

Barr, A., Bird, K., & Castleman, B. L. (2016). Prompting active choice among high-risk borrowers: Evidence from a student loan counseling experiment. EdPolicyWorks Working Paper Series No. 41. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/education_seminar_series/prompting_choice_among_student_borrowers.pdf

Berkner, L., & Choy, S. (2008). Descriptive summary of 2003–04 beginning postsecondary students: Three years later (NCES 2008-174). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Bodner, T. E. (2008). What improves with increased missing data imputations? Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 15(4), 651–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510802339072

Bound, J., Lovenheim, M. F., & Turner, S. (2012). Increasing time to baccalaureate degree in the United States. Education Finance and Policy, 7(4), 375–424. https://doi.org/10.1162/EDFP_a_00074

Bradburn, E. M., Berger, R., Xiaojile, L., Katharin, P., & Rooney, K. (2003). A descriptive summary of 1999–2000 bachelor’s degree recipients 1 year later: With an analysis of time to degree. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2003/2003165.pdf

Britt, L. W., & Hirt, J. B. (1999). Student experiences and institutional practices affecting spring semester transfer students. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1086

Bryan, M., Cooney, D., & Elliott, B. (2019). 2012/17 Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS:12/17) Data File Documentation (NCES 2020-522). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch

Burgstahler, S., Crawford, L., & Acosta, J. (2001). Transition from two-year to four-year institutions for students with disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v21i1.253

Cejda, B. D. (1997). An examination of transfer shock in academic disciplines. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 21(3), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066892970210301

Cejda, B. D., & Kaylor, A. J. (1997). Academic performance of community college transfer students at private and liberal arts colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 21(7), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066892970210704

Chan, M., Kwon, J., Nguyen, D. J., Saunders, K. M., Shah, N., & Smith, K. N. (2019). Indebted over time: Racial differences in student borrowing. Educational Researcher, 48(8), 558–563. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19864969

Chickering, A. W., & Schlossberg, N. K. (2002). Getting the most out of college (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

Contomichalos, S. K. (2014). Issues and obstacles for lateral transfer students to selective colleges. Journal of College Admission, 32(3). http://eduadvise.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Transfer-Student-Article-Fall-2014.pdf

Davies, T. G., & Casey, K. (1999). Transfer student experiences: Comparing their academic and social lives at the community college and university. College Student Journal, 33(1), 60–71.

Delisle, J. (2017, October 12). The Pell Grant proxy: A ubiquitous but flawed measure of low-income student enrollment. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-pell-grant-proxy-a-ubiquitous-but-flawed-measure-of-low-income-student-enrollment/

Dennis, J. M., Calvillo, E., & Gonzalez, A. (2008). The role of psychosocial variables in understanding the achievement and retention of transfer students at an ethnically diverse urban university. Journal of College Student Development, 49(6), 535–550.

DesJardins, S. L., Ahlburg, D. A., & McCall, B. P. (2002). Simulating the longitudinal effects of changes in financial aid on student departure from college. The Journal of Human Resources, 37, 653–679. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069685

Dong, Y., & Peng, C.-Y.J. (2013). Principled missing data methods for researchers. Springerplus, 2, 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-222

Doyle, W. R. (2009). The effect of community college enrollment on bachelor’s degree completion. Economics of Education Review, 28(2), 199–206.

Fauria, R. M., & Slate, J. R. (2014). Persistence rate differences of university students by race: A within groups comparison. International Journal of University Teaching and Faculty Development, 4(1), 1–10.

Fishman, R., & Hiler, T. (2020, September 2). New polling from New America and Third Way on COVID-19's impact on current and future college students. Third Way. www.thirdway.orgmemo/new-polling-from-new-america-third-way-on-covid-19s-impact-on-current-and-future-college-students

Flint, T. A. (1997). Predicting student loan defaults. The Journal of Higher Education, 68(3), 322–354. https://doi.org/10.2307/2960044

Fox, J. J., Bartholomae, S., Letkiewicz, J. C., & Montalto, C. P. (2017). College student debt and anticipated repayment difficulty. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 47(2), 111–135.

Francies, C., & Anderson, L. (2020, February 24). 50-State comparison: Transfer and articulation policies. Education Commission of the States. https://www.ecs.org/transfer-and-articulation-policies-db/

Gao, H., Hughes, W. W., O’Rear, M. R., & Fendley, W. R. (2002, June). Developing structural equation models to determine factors contributing to student graduation and retention: Are there differences for native students and transfers? In Paper presented at the Annual Forum of the Association for Institutional Research, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Gervais, M., & Ziebarth, N. L. (2019). Life after debt: Postgraduation consequences of federal student loans. Economic Inquiry, 57(3), 1342–1366.

Goldrick-Rab, S., Kelchen, R., Harris, D. N., & Benson, J. (2016). Reducing income inequality in educational attainment: Experimental evidence on the impact of financial aid on college completion. American Journal of Sociology, 121(6), 1762–1817. https://doi.org/10.1086/685442

González Canché, M. S. (2014). Is the community college a less expensive path toward a bachelor’s degree? Public 2- and 4-year colleges’ impact on loan debt. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(5), 723–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2014.11777346

Hagedorn, L. S., & Castro, C. R. (1999). Paradoxes: California’s experience with reverse transfer students. New Directions for Community Colleges, 106, 15–26.

Hahs-Vaughn, D. L. (2005). A primer for using and understanding weights with national datasets. The Journal of Experimental Education, 73, 221–248. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.73.3.221-248

Handel, S. J., & Williams, R. W. (2012). The promise of the transfer pathway: Opportunity and challenge for community college students seeking the baccalaureate degree. The College Board.

Harrast, S. A. (2004). Undergraduate borrowing: A study of debtor students and their ability to retire undergraduate loans. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 34(1), 21–37.

Hayes, A. F., & Montoya, A. K. (2017). A tutorial on testing, visualizing, and probing an interaction involving a multicategorical variable in linear regression analysis. Communication Methods and Measures, 11(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1271116

Herzog, S. (2018). Financial aid and college persistence: Do student loans help or hurt? Research in Higher Education, 59, 273–301.

Hills, J. R. (1965). Transfer shock: The academic performance of the junior college transfer. The Journal of Experimental Education, 33(3), 201–215.

Hodara, M., Martinez-Wenzl, M., Stevens, D., & Mazzeo, C. (2016). Improving credit mobility for community college transfer students: Finding and recommendations from a 10-state study. Education Northwest.

Hossler, D., Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Ziskin, M., Chen, J., Zerquera, D., & Torres, V. (2012, February). Transfer and Mobility: A National View of Pre-degree Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Signature Report. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Houle, J. N., & Addo, F. R. (2019). Racial disparities in student debt and the reproduction of the fragile black middle class. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 5(4), 562–577.

Hu, X., Ortagus, J. C., & Kramer, D. A. (2018). The community college pathway: An analysis of the costs associated with enrolling initially at a community college before transferring to a 4-year institution. Higher Education Policy, 31(3), 359–380.

Huang, F. L. (2016). Alternatives to multilevel modeling for the analysis of clustered data. The Journal of Experimental Education, 84(1), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2014.952397

Hussar, B., Zhang, J., Hein, S., Wang, K., Roberts, A., Cui, J., Smith, M., Bullock Mann, F., Barmer, A., & Dilig, R. (2020). The Condition of Education 2020 (NCES 2020-144). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020144

Ishitani, T. T., & McKitrich, S. A. (2010). About transfer: The engagement of community college students at a four-year collegiate institution. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 34(3), 576–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920701831522

Jackson, B. A., & Reynolds, J. R. (2013). The price of opportunity: Race, student loan debt, and college achievement. Sociological Inquiry, 83(3), 335–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12012

Jenkins, D., & Fink, J. (2015). What we know about transfer. Columbia University.

Jenkins, D., & Fink, J. (2016). Tracking transfer: New measures of institutional and state effectiveness in helping community college students attain bachelor’s degrees. Columbia University.

Jones, J. C., & Lee, B. S. (1992). Moving on: A cooperative study of student transfer. Research in Higher Education, 33(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00991976

Kantrowitz, M. (2009). Growth in cumulative education debt at college graduation. Student Aid Policy Analysis. Publisher of FinAid.org and FastWeb.com, July 30, 2009. https://immagic.com/eLibrary/ARCHIVES/GENERAL/MNSTR_US/F090828K.pdf

Kim, J., Chatterjee, S., Young, J., & Moon, U. J. (2017). The cost of access: Racial disparities in student loan burdens of young adults. College Student Journal, 51(1), 99–114.

King, G., & Nielsen, R. (2019). Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Political Analysis, 27(4), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.11

Laanan, F. S. (2001). Transfer student adjustment. New Directions for Community Colleges, 114(3), 5–13.

Laanan, F. S. (2007). Studying transfer students: Part II: Dimensions of transfer students’ adjustment. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 31(1), 37–59.

Laanan, F. S., Starobin, S. S., & Eggleston, L. E. (2010). Adjustment of community college students at a four-year university: Role and relevance of transfer student capital for student retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 12(2), 175–209.

Lichtenberger, E., & Dietrich, C. (2017). The community college penalty? Examining the bachelor’s completion rates of community college transfer students as a function of time. Community College Review, 45(1), 3–32.

Long, B. T., & Kurlaender, M. (2009). Do community colleges provide a viable pathway to a baccalaureate degree? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31(1), 30–53. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373708327756

Maliszewski Lukszo, C., & Hayes, S. (2020). Facilitating transfer student success: Exploring sources of transfer student capital. Community College Review, 48(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552119876017

McCormick, A. C. (2003). Swirling and double-dipping: New patterns of student attendance and their implications for higher education. New Directions for Higher Education, 121(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.98

McCormick, A. C., & Carroll, C. D. (1997). Transfer behavior among beginning post-secondary students, 1989–94 (No. NCES 97-266). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

McGuire, S. P., & Belcheir, M. (2013). Transfer student characteristics matter. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 15(1), 37–48.

Melguizo, T., Kienzl, G. S., & Alfonso, M. (2011). Comparing the educational attainment of community college transfer students and four-year college rising juniors using propensity score matching methods. The Journal of Higher Education, 82(3), 265–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2011.11777202

Monaghan, D. B., & Attewell, P. (2015). The community college route to the bachelor’s degree. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 70–91. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373714521865

Pascarella, E. (1999). New studies track community college effects on students. Community College Journal, 69(6), 8–14.

Peter, K., & Cataldi, E. F. (2005). The road less traveled? Students who enroll in multiple institutions (NCES 2005-157). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Government Printing Office.

R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/

Rhine, T. J., Milligan, D. M., & Nelson, L. R. (2000). Alleviating transfer shock: Creating an environment for more successful transfer students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 24(6), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920050137228

Roberts, J., & McNeese, M. N. (2010). Student involvement/engagement in higher education based on student origin. Research in Higher Education Journal, 7. http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/09346.pdf

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley.

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Huie, F., Wakhungu, P. K., Bhimdiwali, A., Nathan, A., & Hwang, Y. (2018, July). Transfer and Mobility: A National View of Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2011 Cohort (Signature Report No. 15). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Wakhungu, P. K., Yuan, X., Nathan, A., & Hwang, Y. (2016, November). Completing College: A National View of Student Attainment Rates. Fall 2010 cohort (Signature Report No. 12). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Simone, S. A. (2014). Transferability of Postsecondary Credit Following Student Transfer or Coenrollment (NCES 2014-163). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics.

Spencer, G. (2019). Can transfer guides improve the uptake of major prerequisites? Evidence from Ohio’s transfer and articulation policy reform. Research in Higher Education, 60(4), 458–484.

Taylor, J. L., & Jain, D. (2017). The multiple dimensions of transfer: Examining the transfer function in American higher education. Community College Review, 45(4), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552117725177

Townsend, B. K. (1995). Community college transfer students: A case study of survival. The Review of Higher Education, 18(2), 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.1995.0022

Townsend, B. K. (2008). “Feeling like a freshman again”: The transfer student transition. New Directions for Higher Education, 144(4), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.327

Townsend, B. K., & Dever, J. (1999). What do we know about reverse transfer students? Understanding the impact of reverse transfer students on community colleges. New Directions for Community Colleges, 106(2), 5–14.

Townsend, B. K., & Wilson, K. (2006). “A hand hold for a little bit”: Factors facilitating the success of community college transfer students to a large research university. Journal of College Student Development, 47(4), 439–456. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2006.0052

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2017, August 14). Higher education: Students need more information to help reduce challenges in transferring college credits. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-574

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 2–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03

Wawrzynski, M. R., & Sedlacek, W. E. (2003). Race and gender differences in the transfer student experience. Journal of College Student Development, 44(4), 489–501.

Weiss, M. L., McKelfresh, D. A., & Yang, R. K. (2006). Transfer student marginality. Journal of Student Affairs, 15, 50–57.

Witteveen, D., & Attewell, P. (2019). The social dimensions of student debt: A data mining analysis. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 49(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.55504/0884-9153.1683

Xu, D., Jaggars, S. S., Fletcher, J., & Fink, J. E. (2018a). Are community college transfer students “a good bet” for 4-year admissions? Comparing academic and labor-market outcomes between transfer and native 4-year college students. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(4), 478–502.

Xu, D., Ran, F. X., Fink, J., Jenkins, D., & Dundar, A. (2018b). Collaboratively clearing the path to a baccalaureate degree: Identifying effective 2- to 4-year college transfer partnerships. Community College Review, 46(3), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552118772649

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the Association for Institutional Research and the National Center for Education Statistics. (Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Association for Institutional Research and the National Center for Education Statistics.) We thank AIR staff and NCES Data Institute organizers, particularly Tinsley Smith, Adam Ross Nelson, and Sean Simone, for their support and for sharing their knowledge of NCES survey data and providing feedback on early drafts of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shirley, M., Olsen, A., Kim, S. et al. Heading in the Right Direction? Examining the Relationship of Transfer Patterns and Income Status on College Student Outcomes. Res High Educ 64, 808–833 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-023-09729-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-023-09729-8