Abstract

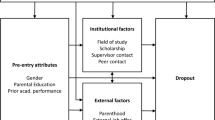

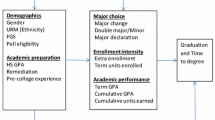

In this paper we study the factors that influence both dropout and (4-year) degree completion throughout university by applying the set of discrete-time methods for competing risks in event history analysis, as described in Scott and Kennedy (2005). In the French-speaking Belgian community, participation rates are very high given that higher education is largely financed through public funds, but at the same time, the system performs very poorly in terms of degree completion. In this particular context, we explore two main questions. First, to what extent is socioeconomic background still a determinant of success for academic careers in a system that, by construction, aims to eliminate economic barriers to higher education? Second, given the high proportion of students who fail their first year and are unable to move to their second year, can authorities promote degree completion and decrease dropout among students who have already experienced a failure? Using the competing risks model, we show that in spite of low entry barriers, students coming from lower socioeconomic background are more vulnerable to dropout along the whole academic path because of financial constraints that prevent them from re-enrolling. Also, our results reveal that, after a failed year, a significantly higher proportion of students who re-enroll in a different field obtain a degree compared to those that re-enroll in the same field, suggesting that universities should rethink the mechanisms available to manage failure and guide student choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Source: OECD (2007),Education at Glance: OECD indicators, OECD, Paris.

See Arias Ortiz and Dehon (2011) for a detailed discussion about how academic performance in Belgian high schools is associated with math-intensive tracks, and how this led to a reform of the entire high school system in the 1970s.

For a detailed review of the main findings and methodological issues of this early group of papers see Arias Ortiz and Dehon (2008).

Unlike the US, in Belgian universities, administrative data at entry does not account for race or ethnic origin. The only information registered is student nationality and thus, all studies related to educational attainment in Belgium only use this variable.

Belgium is a Federal state where communities are responsible for the organization of the educational system since 1988.

Faits et Gestes, Débats & Recherches en Communauté française Wallonie-Bruxelles, revue trimestrielle, hiver 2011.

The general Belgian high school system is the system that prepares students to enter a higher education institution. This excludes students of the technical or the professional system that prepares them to immediately enter the labor market.

The number of students enrolled in higher education is divided more or less equally between university institutions and non-university institutions. As opposed to universities, the non-university institutions offer 3- or 5-year degrees geared towards more practical learning.

The students enrolled in Medicine are not studied in this paper because their degree requires a minimum of seven years of full-time enrollment.

For a complete description of the samples and the degree programs contained in each, see Table 10 in the Appendix.

The complete analysis of the 5-year program sample and a detailed discussion of the cases in which students in this sample present particular or interesting behavior with respect to those in the 4-year program sample is available on the electronic appendix found on-line (http://homepages.ulb.ac.be/~cdehon/research.html).

The field of enrollment is coded into three main groups given that authorities believe at ULB believe that students in science have higher rates of success than students in other domains (Arias Ortiz and Dehon 2008).

In Belgium, the law requires children to start their primary education in the academic year in which they turn six years old.

The difference in success rates observed in the first year at university between students from these two educational systems is analyzed in Arias Ortiz and Dehon (2011).

We call this reorientation.

A full review of the technical considerations justifying why discrete time models are preferable, in educational contexts, to continuous time, is described in Chen and DesJardins (2010).

For more details about these methods see Kleinbaum and Klein (2005).

As explained earlier, a student cannot finish a 4-year career in less than four years, so the hazard probabilities of the outcome degree are equal to zero for the first three years of enrollment. Moreover, concerning the outcome dropout, the definition of “being at risk” for the first three years is computed as in the situation with one single outcome.

Given that very few individuals are still enrolled after eight years at university and in order to keep a large number of observations, we merged individuals who experienced an outcome in their 8th, 9th, 10th of 11th year of enrollment into one category. However, 99 is a relatively small number so it is possible to have some instabilities in the hazard functions for this last period. The estimators in the multivariate model related to the last period of enrollment should be interpreted with caution.

In our case, we have to bear in mind that surviving means experiencing no outcome, so only still being enrolled.

The most flexible baseline function is given by a set of T time dummies representing each period of time.

We could parametrize the time effect by eliminating one time dummy and including a stand-alone intercept (not multiplied by a time variable). However, this type of common representation is less intuitive for survival models, and thus, we decided to keep one intercept by time period.

It is important to highlight that these hazard probabilities are not exactly equal to those seen in Table 3 because, in the first section, we analyzed the whole sample and not the smallest complete sample required for estimating the model. The results, however, hold independently of the sample we use.

There are three assumptions required for estimating a discrete-time hazard model: (i) the linearity assumption, (ii) no unobserved heterogeneity and (iii) the proportionality assumption. The first one is not relevant in our case given that the entire set of explanatory variables is composed of dummy variables. The second assumption is derived from the fact that discrete-time hazards models do not include an error term, implying that all the variation in the hazards profiles comes from the variation in the value of the covariates. The problem with this assumption is of course that omitting an important predictor from the model can then have severe consequences on the estimates. But the potential biases are diminished if a fully flexible specification for the baseline hazard function is used, which is the case in our model. One easy way to solve this problem is to incorporate a random error term in the model (Allison, 1982). This solution is already well developed for discrete time proportional hazard model (see Stephen Jenkin’s website) but not yet available for competing risks models.

This is already an important issue in medicine, as a large majority of medical students are women, and evidence shows that they tend to exit earlier the labor market and those who stay, work less hours (Lorant and Artoisenet, 2004).

So far, the university offers personalized counseling at the end of the first year only for student that make a personal request.

References

Ai, C., Norton, E. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80, 123–129.

Alaluf, M., Imatouchan, N., Marage, P., Pahaut, S., Sanvura, R., Valkeneers, A., Vanheerswynghels, A. (2003). "Les filles face aux é tudes scientifiques. Réussite scolaire et inégalités d’orientation", Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

Allen, D. (1999). Desire to finish college: An empirical link between motivation and persistence. Research in Higher Education, 40(4), 461–485.

Allison, P., D. (1982). Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories, In S. Leinhardt (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 61–98). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Arias Ortiz, E., Dehon, C. (2008). What are the factors that influence success at university? a case study in Belgium. CESifo Economic Studies, 54(2), 121–148.

Arias Ortiz, E., Dehon, C.(2011). High school curriculum and success at university: The effect of student choices, mimeo.

Bahr, P. (2008). Does mathematics remediation work?: A comparative analysis of academic attainment among community college students. Research in Higher Education, 49(5), 420–450.

Becker, G.S., Tomes, N. (1976). Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children, The Journal of Political Economy, 84(4), Part 2: Essays in labor economics in honor of H.Gregg Lewis, 143–62.

Bruffaerts, C., Dehon, C., Guisset, B. (2011). Can schooling and socio-economic level be a millstone to a student’s academic success?, mimeo.

Chen, R., DesJardins, S. (2010). Investigating the impact of financial aid on student dropout risks: Racial and ethnic differences, The Journal of Higher Education, 81 (2).

D’Addio, A., Rosholm, M. (2005). Exits from temporary jobs in Europe: A competing risks analysis. Labour Economics, 12(4), 449–468.

Demeulemeester, J.-L., Rochat, D. (1995). Impact of individuals characteristics and sociocultural environment on academic success. International Advances in Economic Research, 1(3), 278–87.

DesJardins, S., Ahlburg, D., McCal, B. (1999). An event history model of student departure. Economics of Education Review, 18(3), 375–390.

DesJardins, S., Ahlburg, D., McCall, B. (2002a). A temporal investigation of factors related to timely degree completion. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(5), 555–581.

DesJardins, S., Ahlburg, D., McCall, B. (2002b). Simulating the longitudinal effects of changes in financial aid on student departure from college. The Journal of Human Resources, 37(3), 653–679.

Dolton, P., van der Klaauw, W. (1999). The turnover of teachers: A competing risks explanation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(3), 543–550.

Droesbeke, J.-J., Hecquet, I., Wattelar, C. (2001). La population étudiante: Description, évolution et perspectives, Bruxelles: Editions de l’Université Libre de Bruxelles and Editions Ellipses.

Droesbeke, J.-J., De Kerchove A.-M., Lambert J.-P., Vermandele C. (2005). Enquête sur les trajectoires étudiantes à à l’entr ée de l’enseignement supérieur de la Communauté Française de Belgique, Colloque francophone sur les sondages (24–27 mai), Société Française de Statistique.

Hosmer, D., Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression, New York: Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics.

Hu, S., John, E.S. (2001). Student persistence in a public higher education system: Understanding racial and ethnic difference. The Journal of Higher Education, 72(3), 265–286.

Ishitani, T., DesJardins, S. (2002–2003). A longitudinal investigation of dropout from college in the United States. Journal of College Student Retentions 4 (2):173–201

Ishitani, T., Snident, K.G. (2006). Longitudinal effects of college preparation programs on college retention. IR Applications, 9,1–10.

Jakobsen, V., Rosholm, M. (2003). Dropping out of school? a competing risks analysis of young immigrants’ progress in the educational system, IZA Discussion Paper series, No. 918.

Kleinbaum, D., Klein, M. (2005). Survival analysis: A self-learning text (2nd edn.), New York: Springer.

Lessard, C., Santiago, P., Hansen, J., & Müller Kucera, K. (2004). Attracting, developing and retaining effective teachers. Country Note: The French Community of Belgium, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Education and Training Policy Division.

Lorant, V., Artoisenet, C. (2004). La féminisation des é tudes et de l’activité médical, Louvain Medical, 123.

Murtaugh, P., Burns, L., Schuster, J. (1999). Predicting the retention of university students. Research in Higher Education, 40(3), 355–371.

Munro, B. (1981). Dropouts from higher education: Path analysis of a national sample. American Educational Research Journal, 18(2), 133–141.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2007). Education at glance: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

Resche-Rigon, M., Azoulay, E., Chevret, S. (2006). Evaluating mortality in intensive care units: Contribution of competing risks analyses, Critical Care, 10(1).

Scott, M., Kennedy, B. (2005). Pitfalls in pathways: Some perspectives on competing risks event history analysis in education research. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 30(4), 413–442.

Singer, J., Willett, J. (1993). It’s about time: Using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. Journal of Educational Statistics, 18(2), 155–195.

Singer, J., Willett, J. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45 ,89–125.

Tinto, V. (1988). Stages of student departure: Reflections on the longitudinal character of student leaving. Journal of Higher Education, 59,438–455.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd edn.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Vieillevoye, S., Wathelet, V., Romainville, M. (2011). La Il faut corriger ce titre par: La démarche (sans espace) et éliminer double a : une transposition de la recherche vers l’intervention, In Romainville M. and Michaut Ch. (directors), Réussite, échec et abandon dans l’enseignement supé rieur, De Boeck.

Willett, J., Singer, J. (1991). From whether to when: New methods for studying student dropout and teacher attrition. Review of Educational Research, 61(4), 407–450.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge research support from FRFC (Fonds de Recherche Fondamentale Collective) and from the ARC contract of the Communauté Française de Belgique.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arias Ortiz, E., Dehon, C. Roads to Success in the Belgian French Community’s Higher Education System: Predictors of Dropout and Degree Completion at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. Res High Educ 54, 693–723 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9290-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9290-y