Abstract

We use a unique loan-level dataset to compare portfolio and securitized commercial real estate loans. The paper documents how the types of loans banks choose to hold in their portfolios differ substantially from the types of loans the same banks securitize. Banks tend to hold loans that are “non-standard” in some observable dimension. These loans are riskier and more likely to become delinquent or distressed. Conditional on default, we find that banks are significantly more likely to extend portfolio loans than is the case for securitized loans. Our results suggest that banks have a comparative advantage in funding risky assets with contracts that may require flexibility in the event of distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The share of securitization here includes CRE loans held by banks that are not good candidates for securitization, such as construction loans and loans on owner-occupied properties. Later in the paper we restrict our analysis to the pool of bank loans that are potential candidates for securitization, i.e. fixed rate loans on income producing properties.

In other words, the property has tenants making regular payments to the property owner and the loan on the property has a fixed interest rate.

FR Y-14Q Reporting Form and Instructions: http://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/reportforms/reportdetail.aspx?sOoYJ+5BzDZGWnsSjRJKDwRxOb5Kb1hL

We expect that over time, as the collection matures, it will become an invaluable source of information regarding the CRE market and the banks’ participation in that market.

Source: Call Report and Y9C.

As the FR Y-14 is a new data collection, we do not have reliable data for all of the fields that we require for analysis prior to 2012:Q1. As a result we have a left-censored database. We observe the portfolio loans that are still current as of 2012:Q1, but not those that have been originated, held in portfolio, and then resolved prior to that date.

Although this misses the height of the crisis, there is still significant stress on the loans in the sample.

We will refer to fixed-rate loans on income producing properties as fixed-rate income producing loans for the remainder of the paper. The income producing refers to the nature of the collateral, not the loan contract.

The Morningstar data extends back to the mid-1990s. FR Y-14 data available prior to 2012:Q1 lacks key variables needed for our analysis.

The Appendix provides a detailed discussion about the sample construction, including a comparison of descriptive statistics of the sample with the excluded CMBS and bank loans. This supports our contention that the sample is representative of the share of the CRE loan market where securitization is a viable option.

Later in the paper we will shrink the sample even further through a propensity score matching approach to attempt to make the loans in the sample even more comparable.

All of the loans in our sample are income-producing, which means that the initial construction phase has been completed and the vacancy rate has stabilized to normal levels.

Originations in 2012 are limited to those loans originated in 2012Q1.

The definitions of extension and default in Table 4 are independent of each other, they are not mutually exclusive categories.

This relates to differences between decentralized and hierarchical firms (Stein 2002).

This robustness test was made in response to a comment from a discussant, as almost all CMBS loans in our analysis are 10-year term loans.

An editor suggested this specification in case the pricing of the loans was endogenous to the securitization decision,

As a robustness test we re-estimate all these equations replace the securitization dummy with the fitted probability of securitization from column (iii) on Table 5. All the results persist in this specification.

To test this hypothesis that banks engage in efficient recontracting for distressed loans in their portfolio we would ideally compare ultimate loss rates for retained and securitized loans. Unfortunately we do not observe losses or recoveries in the bank data over a sufficient time period.

Specifically, we use the specification that generates the results in column (iii) of Table 5.

Coverage has currently expanded to 32 firms, but we limit our analysis to those firms participating in the initial reporting wave in order to maximize the time available to monitor loan performance.

References

Agarwal, S., Amromin, G., Ben-David, I., Chomsisengphet, S., & Evanoff, D. (2011). The role of securitization in mortgage renegotiation. Journal of Financial Economics, 102, 559–578.

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for “lemons”: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84, 488–500.

Ambrose, B., & Sanders, A. B. (2003). Commercial mortgage (CMBS) default and prepayment analysis. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 26, 179–196.

An, X., Deng, Y., & Gabriel, S. (2011). Asymmetric information, adverse selection, and the pricing of CMBS. Journal of Financial Economics, 100, 304–325.

Archer, W. R., Elmer, P. J., Harrison, D. M., & Ling, D. C. (2002). Determinants of multifamily mortgage default. Real Estate Economics, 30, 445–473.

Black, L., Chu, C. S., Cohen, A., & Nichols, J. B. (2012). Differences across originators in CMBS loan underwriting. Journal of Financial Services Research, 42, 115–134.

Ciochetti, B., Deng, Y., Lee, G., Shilling, J. D., & Yao, R. (2003). A proportional hazard model of commercial mortgage default with origination bias. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 27, 5–23.

Coleman, A. D. F., Esho, N., & Sharpe, I. G. (2006). Does bank monitoring influence loan contract terms? Journal of Financial Services Research, 30, 177–198.

Dehejia, R. H., & Wahba, S. (2002). Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 151–161.

Deng, Y., J.M Quigley, and A.B. Sanders (2004). Commercial mortgage terminations: evidence from CMBS. USC Working paper.

Downs, David H. and Pisun (Tracy) Xu (2014). “Commercial real estate, distress and financial resolution: portfolio lending versus securitization.” Working paper.

Esaki, H., S. L’Heureux, and M.P. Snyderman (1999). Commercial mortgage defaults: an update. Real Estate Finance, 16, 81–86.

Furfine, C. (2010). Deal complexity, loan performance, and the pricing of commercial mortgage backed securities. Kellogg School of Management working paper.

Ghent, A. and R. Valkanov (2013). Advantages and disadvantages of securitization: evidence from commercial mortgages. Working paper.

Keys, B. J., Mukherjee, T., Seru, A., & Vig, V. (2009). Financial regulation and securitization: evidence from subprime loans. Journal of Monetary Economics, 56, 700–720.

Piskorski, T., Seru, A., & Vig, V. (2010). Securitization and distressed loan renegotiation: evidence from the subprime mortgage crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 97, 369–397.

Puranandam, A. (2011). Originate-to-distribute model and subprime mortgage crisis. Review of Financial Studies, 24, 1881–1915.

Snyderman, M. P. (1991). Commercial mortgages: default occurrence and estimated yield impact. Journal of Portfolio Management, 18, 82–87.

Stafford, T., Linder, D., & Jones, R. (2010). CMBS under stress. Frequently asked questions about key provisions in CMBS pooling and servicing agreements addressing mortgage loan modifications. Real Estate Finance, 27(1), 3–6.

Stein, J. C. (2002). Information production and capital allocation: decentralized versus hierarchical firms. Journal of Finance, 57, 1891–1921.

Titman, S., & Tsyplakov, S. (2010). Originator performance, CMBS structures, and the risk of commercial mortgages. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 3558–3594.

Titman, S., Tompaidis, S., & Tsyplakov, S. (2005). Market imperfections, investment flexibility, and default spreads. Journal of Finance, 59, 165–205.

Vandell, K. D., Barnes, W., Hartzell, D., Kraft, D., & Wendt, W. (1993). Commercial mortgage defaults: proportional hazards estimation using individual loan histories. Journal of American Real Estate Urban Economic Association, 21, 451–480.

Acknowledgments

We thank seminar participants at the UF/FSU Real Estate Symposium, the Stress Test Modeling Research Conference, the Interagency Risk Quantification Forum, the AREUEA Annual Meetings, the Southern Finance Association Annual Meetings, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Ohio University, University of Cincinnati, as well as Travis Davidson, Ronel Elul, Emre Ergungor, Mark Lueck, Wayne Passmore, and Gokhan Torna for helpful comments, and Joseph Cox and Erin McCarthy for research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Appendix Construction of Data Set for Estimation

Appendix Construction of Data Set for Estimation

We draw our loan sample from two distinct data bases, the Morningstar CMBS database and the FR Y-14 Q CRE schedule. This appendix provides some additional detail on the construction of the database, including some characteristics of the portions of both databases that were excluded from the analysis.

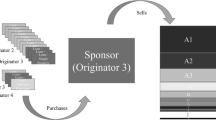

The CMBS data is drawn from the Morningstar database, which covers the CMBS market at the deal level. These deals include loans originated by banks, insurance companies, conduits and others. As of 2012:Q1, approximately 59 % of active CMBS loans were originated by banks. We limit our analysis to fixed rate loans originated by firms that are also in the FR Y-14 collection, which accounts for 84 % of CMBS bank originated loans. The FR Y-14 data collection included 19 firms in 2012:Q1.Footnote 21 Within this sample we restrict our analysis to fixed rate loans originated and held by the 8 firms that are also active in the CMBS market. The decision to restrict the sample to both fixed rate loans and to the same group of firms active in both the markets was made to minimize concerns regarding the endogenity of the securitization decision. We limit our analysis to a group of loans that have similar loan structures and are all from firms that had the option to either securitize or hold loans on their portfolio.

Appendix Table 9 below compares the portfolio characteristics of our estimation sample with the portions of the CMBS and bank portfolio that we excluded from our analysis. The first two columns report the characteristics from banks in the CMBS sample that are not FR Y-14 reporters and from FR Y-14 reporters that are not active in the CMBS market. The third and fourth columns report the characteristics of the adjustable and mixed-rate loans from the sample of nine banks active in CMBS market that also were FR Y-14 reporters. This table reflects the active portfolios as of 2012:Q1.

The outlier in these six portfolios is clearly the adjustable rate CRE loans in CMBS portfolio that were originated by our sample of nine banks. As of 2012:Q1 there were very few of these adjustable rate CMBS loans still active. They were dominated by a small number of very larger hotel loans, many of which were in default. The negative spread to Treasuries reflects that many of these loans may have been indexed to baseline rates other than Treasuries at origination.

Restricting ourselves to the other portfolios, the patterns we observe in our sample repeat. CMBS loans are larger with higher LTVs ratios and occupancy rates in each set of samples. Bank loans have higher debt yields and spreads to Treasuries than CMBS loans. Finally, as of 2012:Q1 more CMBS loans were in default than the bank loan portfolios.

Appendix Fig. 7 below provides additional evidence that the adjustable rate portfolios for the CMBS portfolios are fundamentally different. CMBS adjustable rate loans from our sample of nine banks have some of the shortest portfolio distributions in our sample while bank adjustable rate loans have some of the longest. The differences in the distribution of the original term between bank and CMBS loans between the fixed rate loans in our sample and the total portfolio from originators outside our sample are however quite similar.

Appendix Fig. 8 below shows the distribution across our six portfolios by property type. Again the adjustable rate CMBS loans from our sample of nine banks represents a strong outlier, being dominated by hotel loans while adjustable rate loans in bank portfolios are dominated by multifamily loans. The property distribution for CMBS and bank loans from our sample of nine banks is similar to the distribution we observe from the originators we exclude from our sample. These figures support our contention that our sample does provide a representative sample to examine CMBS vs. bank portfolios, and supports our decision to exclude the adjustable rate mortgages.

The larger size for CMBS loans may reflect differences in tenant quality, and therefore credit risk, between CMBS and bank loans. In the retail space the larger properties, such are often “anchored” by high quality tenants than those served by smaller “strip” centers. Unfortunately we lack the detailed information on tenant quality in both databases. The size of the property, and the related loan balance, may be used to proxy for the presence of such “anchored” retail properties, and similar properties with high quality tenants in other property types. Appendix Table 10 below reports the differences in the average balance at origination between CMBS and banks by property type. We see here that CMBS loans consistently have larger balances at origination than bank loans across all property types.

Insert text on how ARM portfolios are different, in particular in CMBS, but out of sample portfolios are similar.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Black, L., Krainer, J. & Nichols, J. From Origination to Renegotiation: A Comparison of Portfolio and Securitized Commercial Real Estate Loans. J Real Estate Finan Econ 55, 1–31 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9548-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9548-1