Abstract

We examine whether an increase in ETF ownership is accompanied by a decline in pricing efficiency for the underlying component securities. Our tests show an increase in ETF ownership is associated with (1) higher trading costs (bid-ask spreads and market liquidity), (2) an increase in “stock return synchronicity,” (3) a decline in “future earnings response coefficients,” and (4) a decline in the number of analysts covering the firm. Collectively, our findings support the view that increased ETF ownership can lead to higher trading costs and lower benefits from information acquisition. This combination results in less informative security prices for the underlying firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the terms “pricing efficiency” and “informational efficiency” interchangeably. Both refer to the speed and efficiency with which price incorporates new information. Empirically, we use several proxies to measure informational efficiency, including “price synchronicity” (SYNCH), “future earnings response coefficients” (FERC), and the number of analysts covering a firm (ANALYST).

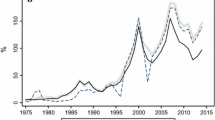

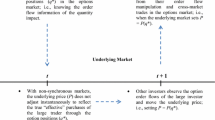

Several models predict noise investors will migrate to index-like instruments because their losses to informed traders are lower in these markets than in the market for individual securities (Rubinstein 1989; Subrahmanyam 1991; Gorton and Pennacchi 1993). Empirically, we have observed such a migration from actively managed assets to passively managed ETFs in recent years. As of June 2015, total ETF trading is close to 28% of the total daily value traded on US equity exchanges (Pisani 2015).

Note that the siphoning of liquidity from component securities can occur with other basket securities as well, such as open-end index funds. However, a key difference between ETFs and index-linked open-end funds is that ETF shares can be traded throughout the day, while transactions with open-end funds occur only at the end of the day and only at net asset value (NAV). Thus ETFs are a more attractive instrument for uninformed traders who trade for speculative reasons, while index funds are better suited to longer term buy-and-hold investors. In section 2, we explain in detail the implications of this difference for our tests.

We use annual holding periods to test our hypotheses because we expect the information-related effects of ETF ownership changes to be experienced gradually over time. Our inferences are the same if we use quarterly panels.

To improve our ability to identify the consequences of increased ETF ownership in a cleaner setting, we focus mainly on analyzing the associations of lagged changes in ETF ownership with firms’ trading costs and measures of pricing efficiency.

Compared to Hamm (2014), we use alternative measures of stock liquidity, include different control variables, examine annual versus quarterly observations, and use a more complete firm-level longitudinal data set. Our main findings with respect to the effect of ETF ownership on stock liquidity are consistent with those of Hamm (2014). It should be noted that Hamm (2014) does not examine the implications of ETF ownership on the informational efficiency of security prices.

Sullivan and Xiong (2012) note that, while passively managed funds represent only about one-third of all fund assets, their average annual growth rate since the early 1990s is 26%, double that of actively managed assets. Much of this increase has been in the form of ETFs. According to Madhavan and Sobczyk (2014), as of June 2014, there were 5217 global ETFs representing $2.63 trillion in total net assets.

Specifically, unlike ETFs, open-end funds do not provide a ready intraday market for deposits and redemptions with a continuous series of available transaction prices. Hence investors may not know with sufficient certainty the cash-out value of redemption before they must commit it.

Note that ETFs are most likely to be successful when the underlying securities are relatively less liquid or difficult to borrow (thus creating an equilibrium demand for the ETF shares, with its lower trading costs). For example, the highly popular small-cap ETF, IWM, is based on the Russell 2000 index. While the underlying securities are typically less liquid (they represent the 2000 stocks in the Russell Index that are below the largest 1000), IWM itself is over $26 billion in assets and trades at extremely low costs.

What happens if the cost of private information remains constant? In that case, pricing efficiency may not be affected by an exodus of uninformed traders. This result derives because the following two opposing forces are at work.

a. As uninformed traders exit the market the profits from trading with them as an informed trader becomes smaller.

b. As fewer informed traders purchase private signals, the value of being one of the remaining informed traders becomes larger.

The net effect is that fewer informed traders will individually make more money, with no net change in the economy-wide value of becoming informed (which remains equal to the information cost). Although the source of noise differs in the models of Verrecchia (1982) and the Grossman and Stiglitz (1980), the same result obtains in both. In both, pricing efficiency will be unaffected by an exodus of uninformed traders if information costs remain constant. We are grateful to the editor for pointing this out.

We test our hypotheses using annual panels because we expect the effect of increased ETF ownership to manifest itself gradually over time after an increase in ETF ownership. Figure 2 presents a sample construction timeline for the key empirical variables used in our tests. Most of our analyses are done using annual changes in ETF ownership, returns, and earnings (Panel A). However, in our replication and reconciliation of the Glosten et al. results, we used quarterly data (Panel B) to match their analyses.

Prior research on the relation between bid-ask spreads and institutional ownership is mixed. Glosten and Harris (1999) suggest that higher levels of concentrated institutional ownership will increase bid-ask spreads, while higher levels of dispersed institutional ownership might encourage competition that reduces bid-ask spreads.

Our inferences are the same when we use the residual from the regression model ∆ETF it = β 0 + β 1∆INST it + ε it as a measure of change in ETF ownership that is orthogonal to the change in the level of institutional ownership.

In untabulated analyses, we explore the sensitivity of our inferences to the inclusion of year fixed effects. We do so to address concerns that the inclusion of year fixed effects limits our analyses to the variation in changes in ETF ownership relative to other firms in the same year, while ignoring the variation in total average year-over-year changes in ETF ownership (which may also have a significant explanatory power for variation in the dependent variables). Our inferences remain the same under the alternative specification that excludes year fixed effects. We tabulate results controlling for year fixed effects, because we believe that controlling for unobserved time-specific effects helps us better isolate the effects of changes in ETFs on variables of interest. We thank the referee for raising this issue.

We adopt this model of returns to measure firm-specific adjusted R2 (and consequently synchronicity) because it is the most frequently used in the literature (Piotroski and Roulstone 2004; Hutton et al. 2009; Chan and Chan 2014). To ensure that our inferences are not affected by the method chosen to estimate firm-specific adjusted R2, we also estimate synchronicity using the methodology outlined by Crawford et al. (2012) and Li et al. (2014). Our inferences are the same when we use these alternate measurement techniques.

In computing SYNCH it , we exclusively use adjusted\( {R}_{it}^2 \) values. Following Crawford et al. (2012), we truncate the sample of adjusted \( {R}_{it}^2 \) values at 0.0001.

Note that our main identification strategy is to link changes in ETF ownership to subsequent changes in the variables of interest. An alternative approach is to identify a discontinuity in ETF ownership arising from an exogenous event (an event unrelated to firms’ trading costs or information environment). For example, Chang et al. (2015) use a regression discontinuity (RD) design to study the effect of Russell 2000 index membership on stock returns. In an attempt to adopt the same strategy, we obtained their dataset of instrumented Russell membership changes and closely follow their approach. Unfortunately, we found that ETF ownership does not change significantly immediately surrounding Russell 2000 index inclusions/exclusions. While this result is consistent with their finding of no relation between this event and changes in overall institutional ownership, it unfortunately means that the Russell 2000 membership reconstitution is not an effective instrument for changes in ETF ownership.

References

Admati, A. R. (1985). A noisy rational expectations equilibrium for multi-asset securities markets. Econometrica, 53, 629–657.

Amihud, Y. (2002). Illiquidity and stock returns: Cross-section and time-series effects. Journal of Financial Markets, 5, 31–56.

Barth, M. E., Kasznik, R., & McNichols, M. (2001). Analyst coverage and intangible assets. Journal of Accounting Research, 39, 1–34.

Ben-David, I., Franzoni, F., & Moussawi, R. (2015). Do ETFs increase volatility? Working Paper: Ohio State University.

Bhattacharya, A., & O’Hara, M. (2016). Can ETFs increase market fragility? Effect of information linkages on ETF markets. Working paper: Cornell University.

Black, F. (1986). Noise. Papers and proceedings of the forty-fourth annual meeting of the American Finance association. Journal of Finance, 41, 529–543.

Broman, M. S. (2013). Excess co-movement and limits-to-arbitrage: Evidence from exchange-traded funds. Working paper: York University.

Chan, K., & Chan, Y. C. (2014). Price informativeness and stock return synchronicity: Evidence from the pricing of seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 114, 36–53.

Chang, Y. C., Hong, H., & Liskovich, I. (2015). Regression discontinuity and the price effects of stock market indexing. Review of Financial Studies, 28, 212–246.

Chen, G., & Strother, T. S. (2008). On the contribution of index exchange traded funds to price discovery in the presence of price limits without short selling. Working paper: University of Otago, New Zealand.

Choi, J., Myers, L. A., Zang, Y., & Ziebart, D. A. (2011). Do management EPS forecasts allow returns to reflect future earnings? Implications for the continuation of management’s quarterly earnings guidance. Review of Accounting Studies, 16, 143–182.

Collins, D., Kothari, S., Shanken, J., & Sloan, R. (1994). Lack of timeliness versus noise as explanations for low contemporaneous return-earnings association. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 18, 289–324.

Cong, L. W., & Xu, D. (2016). Rise of factor investing: Asset prices, informational efficiency, and security design. Working paper: University of Chicago.

Copeland, T., & Galai, D. (1983). Information effects on the bid-ask spread. The Journal of Finance, 38, 1457–1469.

Corwin, S., & Schultz, P. (2012). A simple way to estimate bid-ask spreads from daily high and low prices. The Journal of Finance, 67, 719–759.

Crawford, S. S., Roulstone, D. T., & So, E. C. (2012). Analyst initiations of coverage and stock return synchronicity. The Accounting Review, 87, 1527–1553.

Da, Z., & Shive, S. (2013). Exchange-traded funds and equity return correlations. Working paper: University of Notre Dame.

Diamond, D. W., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1981). Information aggregation in noisy rational expectations model. Journal of Financial Economics, 9, 221–235.

Durnev, A., Morck, R., Yeung, B., & Zarowin, P. (2003). Does greater firm-specific return variation mean more or less informed stock pricing? Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 797–836.

Durnev, A., Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2004). Value-enhancing capital budgeting and firm-specific stock return variation. The Journal of Finance, 59, 65–105.

Ettredge, M., Kwon, S. Y., & Smith, D. (2005). The impact of SFAS no. 131 business segment data on the market’s ability to anticipate future earnings. The Accounting Review, 80, 773–804.

Fama, E., & French, K. (1992). The cross-section of expected returns. Journal of Finance, 46, 427–466.

Fang, Y., & Sang, G. C. (2012). Index price discovery in the cash market. Working paper: Louisiana State University.

Glosten, L., & Harris, L. (1999). Estimating the components of the bid/ask spread. Journal of Financial Economics, 21, 123–142.

Glosten, L., Nallareddy, S., & Zou, Y. (2016). ETF trading and informational efficiency of underlying securities. Working paper: Columbia University.

Gorton, G. B., & Pennacchi, G. G. (1993). Security baskets and index-linked securities. The Journal of Business, 66, 1–27.

Gow, I., Ormazabal, G., & Taylor, D. (2010). Correcting for cross-sectional and time-series dependence in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 85, 483–512.

Goyenko, R. Y., Holden, G. W., & Trzcinka, C. A. (2009). Do liquidity measures measure liquidity? Journal of Financial Economics, 92, 153–181.

Grossman, S. (1989). The informational role of prices. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Grossman, S., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1980). On the impossibility of informationally efficient markets. American Economic Review, 70, 393–408.

Hamm, S. J. W. (2014). The effects of ETFs on stock liquidity. Working paper: Ohio State University.

Hasbrouck, J. (2003). Intraday price formation in U.S. equity index markets. The Journal of Finance, 58, 2375–2399.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35, 519–530.

Hellwig, M. R. (1980). On the aggregation of information in competitive markets. Journal of Economic Theory, 22, 477–498.

Holden, C. (2009). New low-frequency spread measures. Journal of Financial Markets, 12, 778–813.

Hutton, A., Marcus, A., & Tehranian, H. (2009). Opaque financial reports, R2, and crash risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 94, 67–86.

Ivanov, S. I., Jones, F. J., & Zaima, J. K. (2013). Analysis of DJIA, S&P 500, S&P 400, NASDAQ 100 and Russell 2000 ETFs and their influence on price discovery. Global Finance Journal, 24, 171–187.

Jiambalvo, J., Rajgopal, S., & Venkatachalam, M. (2002). Institutional ownership and the extent to which stock prices reflect future earnings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19, 117–145.

Jin, L., & Myers, S. (2006). R-squared around the world: New theory and new tests. Journal of Financial Economics, 79, 257–292.

Kothari, S., & Sloan, R. (1992). Information in prices about future earnings: Implications for earnings response coefficients. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 15, 143–171.

Krause, T., Ehsani, S., & Lien, D. (2014). Exchange-traded funds, liquidity and volatility. Working paper. University of Texas at San Antonio.

Kyle, A. S. (1985). Continuous auctions and insider trading. Econometrica, 53, 1315–1335.

Kyle, A. S. (1989). Informed speculation with imperfect competition. Review of Economic Studies, 56, 317–356.

Lakonishok, J., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1994). Contrarian investment, extrapolation, and risk. Journal of Finance, 49, 1541–1578.

Lang, M., & Lundholm, R. (1996). Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review, 71, 467–492.

Lee, C. M. C., & So, E. (2015). Alphanomics: The informational underpinnings of market efficiency. Foundations and Trends in Accounting, 9, 59–258.

Lesmond, D., Ogden, J., & Trzcinka, C. (1999). A new estimate of transactions costs. Review of Financial Studies, 12, 1113–1141.

Li, B., Rajgopal, S., & Venkatachalam, M. (2014). R2 and idiosyncratic risk are not inter-changeable. The Accounting Review, 89, 2261–2295.

Lundholm, R., & Myers, L. (2002). Bringing the future forward: The effect of disclosure on the returns-earnings relation. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 809–839.

Madhavan, A., & Sobczyk, A. (2014). Price dynamics and liquidity of exchange-traded funds. BlackRock Inc: Working paper.

Milgrom, P., & Stokey, N. (1982). Information, trade and common knowledge. Journal of Economic Theory, 26, 17–27.

Pedersen, L. H. (2015). Efficiently inefficient: How Smart Money Invests & Market Prices are Determined. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Piotroski, J. D., & Roulstone, D. T. (2004). The influence of analysis, institutional investors, and insiders on the incorporation of market, industry, and firm-specific information into stock prices. The Accounting Review, 79, 1119–1151.

Pisani, R. (2015). Here is why ETFs are a growing part of total trading value, CNBC. http://www.cnbc.com/2015/07/02/heres-why-etfs-are-a-growing-part-of-total-trading-value.html Accessed 2 July 2015.

Ramaswamy, S. (2011). Market structures and systemic risks of exchange-traded funds. Working paper: Bank For International Settlements.

Roll, R. (1984). A simple implicit measure of the effective bid-ask spread in an efficient market. The Journal of Finance, 39, 127–1139.

Rubinstein, M. (1989). Market basket alternatives. Financial Analysts Journal, 45, 20–29.

Subrahmanyam, A. (1991). A theory of trading in stock index futures. The Review of Financial Studies, 4, 17–51.

Sullivan, R., & Xiong, J. (2012). How Index Trading Increases Market Vulnerability. Financial Analysts Journal, 68, 70–84. doi: 10.1007/s11142-017-9400-8.

Verrecchia, R. (1982). Information acquisition in a noisy rational expectations economy. Econometrica, 50, 1415–1430.

Wurgler, J. (2000). Financial markets and the allocation of capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 187–214.

Yu, L. (2005). Basket securities, price formation, and informational efficiency. Working paper: University of Notre Dame. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.862604.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge research assistance from Woo Young Park and Padmasini Venkatachari. We thank Inessa Liskovich and Harrison Hong for kindly providing us with their data on Russell 2000 reconstitutions. We are grateful for helpful suggestions and comments from Russell Lundholm (Editor), Ira Yeung (Discussant), an anonymous referee, Will Cong, Larry Glosten, Ananth Madhavan, Ed Watts, Frank Zhang as well as seminar participants at Emory University, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, Tel Aviv University, UCLA, the University of Iowa, Duke University, and Harvard University (IMO Conference 2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Israeli, D., Lee, C.M.C. & Sridharan, S.A. Is there a dark side to exchange traded funds? An information perspective. Rev Account Stud 22, 1048–1083 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9400-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9400-8

Keywords

- Exchange traded funds (ETFs)

- Informed and unformed traders

- Trading costs

- Informational efficiency

- Pricing efficiency