Abstract

Purpose

Do cancer survivors experience positive changes (i.e., posttraumatic growth; PTG) resulting in better quality of life? The issue has yet to yield consistent notions. This longitudinal study extends the literature on the role of PTG by examining the curvilinear relationship between PTG and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), and explored whether PTG predicts subsequent HRQoL in a quadratic relationship across 2 years following surgery.

Methods

Women with breast cancer (N = 359; Mage = 47.5) were assessed at five waves over two years. On every measurement occasion, PTG measured by the posttraumatic growth inventory and HRQoL measured by SF-36 were assessed. The five waves reflect major medical demands and related challenges in the breast cancer trajectory, in which 1-day, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months after surgery were adopted as the survey timing. In a series of hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analyses, the time-lagged predictions of PTG (i.e., linear, quadratic) on HRQoL were examined, controlling demographic and medical covariates.

Results

The results revealed that the quadratic term of PTG consistently significantly predicted physical and mental health quality of life (PCS and MCS), while the linear term of PTG did not significantly predict PCS or MCS.

Conclusion

With multi-wave longitudinal data, this study demonstrated that the relationship between PTG and HRQoL is curvilinear, and this finding extends to PTG’s prediction of subsequent HRQoL. The quadratic relationship has critical implications for clinical assessment and intervention. Details are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data and material is available on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Sung, H., et al. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249.

Wilson, I. B., & Cleary, P. D. (1995). Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA, 273(1), 59–65.

Ojelabi, A. O., et al. (2017). A systematic review of the application of Wilson and Cleary health-related quality of life model in chronic diseases. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 1–15.

Sumalla, E. C., Ochoa, C., & Blanco, I. (2009). Posttraumatic growth in cancer: Reality or illusion? Clinical Psychology Review, 29(1), 24–33.

Hou, W. K., et al. (2010). Resource loss, resource gain, and psychological resilience and dysfunction following cancer diagnosis: A growth mixture modeling approach. Health Psychology, 29(5), 484–495.

Edmondson, D. (2014). An enduring somatic threat model of posttraumatic stress disorder due to acute life-threatening medical events. Social and personality psychology compass, 8(3), 118–134.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.

Tedeschi, R. G., et al. (2018). Posttraumatic growth: Theory, research, and applications. Routledge.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471.

Lelorain, S., Bonnaud-Antignac, A., & Florin, A. (2010). Long term posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: Prevalence, predictors and relationships with psychological health. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17(1), 14–22.

Weiss, T. (2002). Posttraumatic growth in women with breast cancer and their husbands: An intersubjective validation study. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 20(2), 65–80.

Casellas-Grau, A., Ochoa, C., & Ruini, C. (2017). Psychological and clinical correlates of posttraumatic growth in cancer: A systematic and critical review. Psycho-oncology, 26(12), 2007–2018.

Tomich, P. L., & Helgeson, V. S. (2012). Posttraumatic growth following cancer: Links to quality of life. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(5), 567–573.

Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., & Tomich, P. L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 797–816.

Stanton, A. L., Bower, J. E., & Low, C. A. (2006). Posttraumatic growth after cancer. In L. G. Calhoun & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice (pp. 138–175). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Shand, L. K., et al. (2015). Correlates of post-traumatic stress symptoms and growth in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology, 24(6), 624–634.

Sawyer, A., Ayers, S., & Field, A. P. (2010). Posttraumatic growth and adjustment among individuals with cancer or HIV/AIDS: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 436–447.

Carver, C. S., Lechner, S. C., & Antoni, M. H., et al. (2009). Challenges in studying positive change after adversity: Illusions form research on breast cancer. In C. L. Park (Ed.), Medical illness and positive life change: Can crisis lead to personal transformation? (pp. 51–62). Washington, DC: APA.

Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Lurie-Beck, J. (2014). A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(2), 223–229.

Lechner, S. C., et al. (2006). Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 828–840.

Martin, L., et al. (2017). Quality of life and posttraumatic growth after adult burn: A prospective, longitudinal study. Burns, 43(7), 1400–1410.

Helgeson, V. S., Snyder, P., & Seltman, H. (2004). Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: Identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychology, 23(1), 3–15.

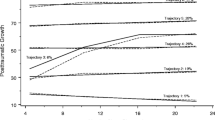

Wang, A.W.-T., et al. (2014). Identification of posttraumatic growth trajectories in the first year after breast cancer surgery. Psycho-Oncology, 23(12), 1399–1405.

Henselmans, I., et al. (2010). Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychology, 29(2), 160–168.

Wang, A.W.-T., et al. (2017). Buffering and direct effect of posttraumatic growth in predicting distress following cancer. Health Psychology, 36(6), 549–559.

Taku, K., et al. (2008). The factor structure of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: A comparison of five models using confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 21(2), 158–164.

Ware, J., et al. (1993). SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center.

Treanor, C., & Donnelly, M. (2015). A methodological review of the Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) and its derivatives among breast cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research, 24, 339–362.

Lu, J., Tseng, H., & Tsai, Y. (2003). Assessment of healthrelated quality of life in Taiwan (I): Development and psychometric testing of SF-36 Taiwan version. Taiwan Journal of Public Health, 22, 501–511.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2022). Hierarchical linear models Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Raudenbush, S. W., et al. (2011). HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1987). Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 147–158.

Engel, J., et al. (2003). Predictors of quality of life of breast cancer patients. Acta Oncologica, 42(7), 710–718.

Konieczny, M., et al. (2020). Quality of life of women with breast cancer and socio-demographic factors. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP, 21(1), 185–193.

Sörensen, J., Rzeszutek, M., & Gasik, R. (2021). Social support and post-traumatic growth among a sample of arthritis patients: Analysis in light of conservation of resources theory. Current Psychology, 40, 2017–2025.

Westphal, M., & Bonanno, G. A. (2007). Posttraumatic growth and resilience to trauma: Different sides of the same coin or different coins? Applied Psychology, 56(3), 417–427.

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301.

Pals, J. L., & McAdams, D. P. (2004). The transformed self: A narrative understanding of posttraumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 65–69.

Barskova, T., & Oesterreich, R. (2009). Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(21), 1709–1733.

Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2013). Posttraumatic growth in clinical practice. Routledge.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Council grant no. 99-2410-H-004-074-MY3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Changhua Christian Hospital. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All participants gave their written informed consent prior to participation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, A.WT., Hsu, WY. & Chang, CS. Curvilinear prediction of posttraumatic growth on quality of life: a five-wave longitudinal investigation of breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res 32, 3185–3193 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03464-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03464-4