Abstract

Purpose

Although strong associations between self-reported health and mortality exist, quality of life is not conceptualized as a cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor. Our objective was to assess the independent association between health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and incident CVD.

Methods

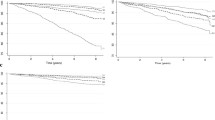

This study used the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke data, which enrolled 30,239 adults from 2003 to 2007 and followed them over 10 years. We included 22,229 adults with no CVD history at baseline. HRQOL was measured using the SF-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores, which range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better HRQOL. Scores were normed to the general US population with mean 50 and standard deviation 10. We constructed a four-level HRQOL variable: (1) individuals with PCS & MCS < 50, (2) PCS < 50 & MCS ≥ 50, (3) MCS < 50 & PCS ≥ 50, and (4) PCS & MCS ≥ 50, which was the reference. The primary outcome was incident CVD (non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), fatal MI or coronary heart disease (CHD) death, fatal and non-fatal stroke). Cox proportional hazards models examined associations between HRQOL and CVD.

Results

Median follow-up was 8.4 (IQR 5.9–10.0) years. We observed 1766 CVD events. Compared to having PCS & MCS ≥ 50, having MCS & PCS < 50 was associated with increased CVD risk (aHR 1.46; 95% 1.24–1.70), adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and CVD risk factors. Associations between MCS & PCS < 50 and CVD were consistent for CHD (aHR 1.54 [1.26–1.89]) and stroke (aHR 1.35 [1.05–1.72]) endpoints.

Conclusions

Given strong, adjusted associations between poor HRQOL and incident CVD, self-reported health may be an excellent complement to current approaches to CVD risk identification.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Benjamin, E. J., Blaha, M. J., Chiuve, S. E., Cushman, M., Das, S. R., Deo, R., de Ferranti, S. D., Floyd, J., Fornage, M., Gillespie, C., Isasi, C. R., Jimenez, M. C., Jordan, L. C., Judd, S. E., Lackland, D., Lichtman, J. H., Lisabeth, L., Liu, S., Longenecker, C. T., Mackey, R. H., Matsushita, K., Mozaffarian, D., Mussolino, M. E., Nasir, K., Neumar, R. W., Palaniappan, L., Pandey, D. K., Thiagarajan, R. R., Reeves, M. J., Ritchey, M., Rodriguez, C. J., Roth, G. A., Rosamond, W. D., Sasson, C., Towfighi, A., Tsao, C. W., Turner, M. B., Virani, S. S., Voeks, J. H., Willey, J. Z., Wilkins, J. T., Wu, J. H., Alger, H. M., Wong, S. S., & Muntner, P. (2017). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 135(10), e146–e603. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000485.

Goff, D. C. Jr., Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Bennett, G., Coady, S., D’Agostino, R. B. Sr., Gibbons, R., Greenland, P., Lackland, D. T., Levy, D., O’Donnell, C. J., Robinson, J. G., Schwartz, J. S., Shero, S. T., Smith, S. C. Jr., Sorlie, P., Stone, N. J., & Wilson, P. W. (2014). 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 63(25 Pt B), 2935–2959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.005.

Colantonio, L. D., Richman, J. S., Carson, A. P., Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Howard, G., Deng, L., Howard, V. J., Safford, M. M., Muntner, P., & Goff, D. C. Jr. (2017) Performance of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease pooled cohort risk equations by social deprivation status. Journal of the American Heart Association. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.005676.

Cook, N. R., & Ridker, P. M. (2014). Further insight into the cardiovascular risk calculator: The roles of statins, revascularizations, and underascertainment in the Women’s Health Study. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(12), 1964–1971. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5336.

D’Agostino, R. B. Sr., Vasan, R. S., Pencina, M. J., Wolf, P. A., Cobain, M., Massaro, J. M., & Kannel, W. B. (2008). General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 117(6), 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.107.699579.

DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K., He, J., & Muntner, P. (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(3), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x.

Dominick, K. L., Ahern, F. M., Gold, C. H., & Heller, D. A. (2002). Relationship of health-related quality of life to health care utilization and mortality among older adults. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 14(6), 499–508.

Howard, V. J., Cushman, M., Pulley, L., Gomez, C. R., Go, R. C., Prineas, R. J., Graham, A., Moy, C. S., & Howard, G. (2005). The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: Objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology, 25(3), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1159/000086678.

Ware, J. Jr., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233.

Zhang, Z. M., Prineas, R. J., & Eaton, C. B. (2010). Evaluation and comparison of the Minnesota Code and Novacode for electrocardiographic Q-ST wave abnormalities for the independent prediction of incident coronary heart disease and total mortality (from the Women’s Health Initiative). The American Journal of Cardiology, 106(1), 18–25.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.02.007.

Luepker, R. V., Apple, F. S., Christenson, R. H., Crow, R. S., Fortmann, S. P., Goff, D., Goldberg, R. J., Hand, M. M., Jaffe, A. S., Julian, D. G., Levy, D., Manolio, T., Mendis, S., Mensah, G., Pajak, A., Prineas, R. J., Reddy, K. S., Roger, V. L., Rosamond, W. D., Shahar, E., Sharrett, A. R., Sorlie, P., & Tunstall-Pedoe, H. (2003) Case definitions for acute coronary heart disease in epidemiology and clinical research studies: A statement from the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; AHA Statistics Committee; World Heart Federation Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Epidemiology and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 108(20):2543–2549. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000100560.46946.ea.

Prineas, R. C. R., & Blackburn, H. (1982). The Minnesota code manual of electrocardiographic findings: Standards and procedures for measurement and classification. Boston: Wright-OSG.

Brown, T. M., Parmar, G., Durant, R. W., Halanych, J. H., Hovater, M., Muntner, P., Prineas, R. J., Roth, D. L., Samdarshi, T. E., & Safford, M. M. (2011). Health Professional Shortage Areas, insurance status, and cardiovascular disease prevention in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(4), 1179–1189. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2011.0127.

Sokolow, M., & Lyon, T. P. (1949). The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. American Heart Journal, 37(2), 161–186.

Levey, A. S., Stevens, L. A., Schmid, C. H., Zhang, Y. L., Castro, A. F. III, Feldman, H. I., Kusek, J. W., Eggers, P., Van Lente, F., Greene, T., & Coresh, J. (2009). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150(9), 604–612.

Schroff, P., Gamboa, C. M., Durant, R. W., Oikeh, A., Richman, J. S., & Safford, M. M. (2017) Vulnerabilities to health disparities and statin use in the REGARDS (reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke) study. Journal of the American Heart Association. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.116.005449.

Burgette, L. F., & Reiter, J. P. (2010). Multiple imputation for missing data via sequential regression trees. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(9), 1070–1076. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq260.

Doove, L. L., Van Buuren, S., & Dusseldorp, E. (2014). Recursive partitioning for missing data imputation in the presence of interaction effects. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 72, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2013.10.025.

Rich, M. W., Chyun, D. A., Skolnick, A. H., Alexander, K. P., Forman, D. E., Kitzman, D. W., Maurer, M. S., McClurken, J. B., Resnick, B. M., Shen, W. K., & Tirschwell, D. L. (2016). Knowledge gaps in cardiovascular care of older adults: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Geriatrics Society: Executive Summary. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(11), 2185–2192. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14576.

Harrell FE, Jr., Lee KL, Mark DB (1996) Multivariable prognostic models: Issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in Medicine 15(4):361–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19960229)15:4%3C361::aid-sim168%3E3.0.co;2-4

Barkhordari, M., Padyab, M., Sardarinia, M., Hadaegh, F., Azizi, F., & Bozorgmanesh, M. (2016). Survival regression modeling strategies in CVD prediction. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 14(2), e32156. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.32156.

Harrell, F. E. (1986) The PHGLM Procedure. In: SUGI Supplemental Library Guide. Version 5 edn. SAS Institute Cary, NC.

Clark, T. G., & Altman, D. G. Developing a prognostic model in the presence of missing data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 56(1):28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00539-5.

Ul-Haq, Z., Mackay, D. F., & Pell, J. P. (2014). Association between physical and mental health-related quality of life and adverse outcomes: A retrospective cohort study of 5,272 Scottish adults. BMC Public Health, 14, 1197. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1197.

Li, C. L., Chang, H. Y., Hsu, C. C., Lu, J. F., & Fang, H. L. (2013). Joint predictability of health related quality of life and leisure time physical activity on mortality risk in people with diabetes. BMC Public Health, 13, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-67.

Myint, P. K., Surtees, P. G., Wainwright, N. W., Luben, R. N., Welch, A. A., Bingham, S. A., Wareham, N. J., & Khaw, K. T. (2007). Physical health-related quality of life predicts stroke in the EPIC-Norfolk. Neurology, 69(24), 2243–2248. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000296010.21252.78.

Sattelmair, J., Pertman, J., Ding, E. L., Kohl, H. W. III, Haskell, W., & Lee, I. M. (2011). Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Circulation, 124(7), 789–795. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.110.010710.

Kodama, S., Saito, K., Tanaka, S., Maki, M., Yachi, Y., Asumi, M., Sugawara, A., Totsuka, K., Shimano, H., Ohashi, Y., Yamada, N., & Sone, H. (2009). Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 301(19), 2024–2035. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.681.

Fredericksen, R. J., Edwards, T. C., Merlin, J. S., Gibbons, L. E., Rao, D., Batey, D. S., Dant, L., Paez, E., Church, A., Crane, P. K., Crane, H. M., & Patrick, D. L. (2015). Patient and provider priorities for self-reported domains of HIV clinical care. AIDS Care, 27(10), 1255–1264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1050983.

Backe, E. M., Seidler, A., Latza, U., Rossnagel, K., & Schumann, B. (2012). The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 85(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0643-6.

Nicholson, A., Kuper, H., & Hemingway, H. (2006). Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146,538 participants in 54 observational studies. European Heart Journal, 27(23), 2763–2774. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl338.

Richardson, S., Shaffer, J. A., Falzon, L., Krupka, D., Davidson, K. W., & Edmondson, D. (2012). Meta-analysis of perceived stress and its association with incident coronary heart disease. The American Journal of Cardiology, 110(12), 1711–1716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.004.

Rugulies, R. (2002). Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease. A review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23(1), 51–61.

Henderson, K. M., Clark, C. J., Lewis, T. T., Aggarwal, N. T., Beck, T., Guo, H., Lunos, S., Brearley, A., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Evans, D. A., & Everson-Rose, S. A. (2013). Psychosocial distress and stroke risk in older adults. Stroke, 44(2), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.112.679159.

Stewart, J. C., Rand, K. L., Muldoon, M. F., & Kamarck, T. W. (2009). A prospective evaluation of the directionality of the depression-inflammation relationship. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23(7), 936–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.011.

Moise, N., Khodneva, Y., Richman, J., Shimbo, D., Kronish, I., & Safford, M. M. (2016) Elucidating the association between depressive symptoms, coronary heart disease, and stroke in black and white adults: The REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Journal of the American Heart Association. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.116.003767.

Burstrom, B., & Fredlund, P. (2001). Self rated health: Is it as good a predictor of subsequent mortality among adults in lower as well as in higher social classes? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55(11), 836–840.

Pakhomov, S. V., Jacobsen, S. J., Chute, C. G., & Roger, V. L. (2008). Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. The American Journal of Managed Care, 14(8), 530–539.

Basch, E. (2017). Patient-reported outcomes—Harnessing patients’ voices to improve clinical care. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(2), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1611252.

Cagle, J., & Bunting, M. (2017). Patient reluctance to discuss pain: Understanding stoicism, stigma, and other contributing factors. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 13(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2017.1282917.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2012.301069.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and participants of the REGARDS study for all of their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org.

Funding

This research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and R01 HL80477 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health. Representatives of the funding agency have been involved in the review of the manuscript but not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. This study was approved by the participating institutions’ Institutional Review Boards. All authors have read and approved the manuscript for submission to Quality of Life Research.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required. All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinheiro, L.C., Reshetnyak, E., Sterling, M.R. et al. Using health-related quality of life to predict cardiovascular disease events. Qual Life Res 28, 1465–1475 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02103-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02103-1