Abstract

Purpose

The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system 29-item profile (PROMIS-29 v2.0) is a widely used health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measure. Summary scores for physical and mental HRQoL have recently been developed for the PROMIS-29 using a general population. Our purpose was to adapt these summary scores to a population of older adults with multiple chronic conditions.

Methods

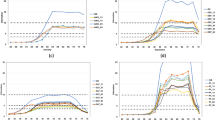

We collected the PROMIS-29 v2.0 for 1359 primary care patients age 65+ with at least 2 of 13 chronic conditions. PROMIS-29 has 7 domains, plus a single-item pain intensity scale. We used exploratory factor analysis (EFA), followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), to examine the number of factors that best captured these eight scores. We used previous results from a recent study by Hays et al. (Qual Life Res 27:1885–1891, 2018) to standardize scoring coefficients, normed to the general population.

Results

The mean age was 80.7, and 67% of participants were age 80 or older. Our results indicated a 2-factor solution, with these factors representing physical and mental HRQoL, respectively. We call these factors the physical health score (PHS) and the mental health score (MHS). We normed these summary scores to the general US population. The mean MHS for our population of was 50.1, similar to the US population, while the mean PHS was 42.2, almost a full standard deviation below the US population.

Conclusions

We describe the adaptation of physical and mental health summary scores of the PROMIS-29 for use with a population of older adults with multiple chronic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cella, D. F. (1995). Measuring quality of life in palliative care. Seminars in Oncology, 22(2 Suppl 3), 73–81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7537908.

Schipper, H., Clinch, J. J., & Olweny, C. L. M. (1996). Quality of life studies: Definitions and conceptual issues. In B. Spilker (Ed.), Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials (pp. 11–23). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers.

Bevans, M., Ross, A., & Cella, D. (2014). Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): Efficient, standardized tools to measure self-reported health and quality of life. Nursing Outlook, 62(5), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2014.05.009.

Chen, J., Ou, L., & Hollis, S. J. (2013). A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organizations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-211.

Ware, J. E. Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

Hays, R. D., Alonso, J., & Coons, S. J. (1998). Possibilities for summarizing health-related quality of life when using a profile instrument. In M. Staquet, R. Hays & P. Fayers (Eds.), Quality of life assessment in clinical trials: Methods and practice (153, p. 143). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Farivar, S. S., Cunningham, W. E., & Hays, R. D. (2007). Correlated physical and mental health summary scores for the SF-36 and SF-12 health survey, V. 1. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5:54. 18.

Hays, R. D., Marshall, G. N., Wang, E. Y. I., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1994). Four-year cross-lagged associations between physical and mental health in the medical outcomes study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 441–449.

Hays, R. D., Spritzer, K. L., Schalet, B., & Cella, D. (2018). PROMIS®-29 v2.0 physical and mental health summary scores. Quality of Life Research, 27(7), 1885–1891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1842-3.

Rose, A. J., et al. (2018). Evaluating the PROMIS-29 v2.0 for use among older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1958-5

Tarlov, A. R., et al. (1989). The medical outcomes study: An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA, 262(7), 925–930.

Edelen, M. O., Rose, A. J., Bayliss, E., Baseman, L., Butcher, E., Garcia, R. E., Tabano, D., & Stucky, B. D. (2017). Patient-reported outcome-based performance measures for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2176.html.

Embretson, S. E., & Reise, S. P. (2000). item response theory for psychologists. London: Psychology Press.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02310555.

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000116.

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1, 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10.

SAS (9.4 ed.). Cary, NC: SAS Corporation.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Hays, R. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1990). The structure of self-reported health in chronic disease patients. Psychological Assessment, 2, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.2.1.22.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Beaumont, J. L., Cella, D., Phan, A. T., Choi, S., Liu, Z., & Yao, J. C. (2012). Comparison of health-related quality of life in patients with neuroendocrine tumors with quality of life in the general US population. Pancreas, 41(3), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0b013e318232804527.

Kazis, L. E., Miller, D. R., Skinner, K. M., Lee, A., Ren, X. S., Clark, J. A. el al (2004). Patient-Reported Measures of Health: The Veterans Health Study. The Journal of ambulatory care management, 27(1), 70–83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14717468.

Revicki, D. A., Kawata, A. K., Harnam, N., Chen, W.-H., Hays, R. D., & Cella, D. (2009). Predicting EuroQol (EQ-5D) scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items and domain item banks in a United States sample. Quality of Life Research, 18, 783–791.

Hays, R. D., Revicki, D. A., Feeny, D., Fayers, P., Spritzer, K. L., & Cella, D. (2016). Using linear equating to map PROMIS global health items and the PROMIS-29 V. 2 Profile measure to the health utilities index—mark 3. Pharmacoeconomics, 34, 1015–1022.

Craig, B. M., Reeve, B. B., Brown, P. M., Cella, D., Hays, R. D., Lipscomb, J., Pickard, A. S., & Revicki, D. A. (2014). US valuation of health outcomes measured using the PROMIS-29. Value in Health, 17(8), 846–853.

Hanmer, J., Cella, D., Feeny, D., Fischhoff, B., Hays, R. D., Hess, R., et al. (2017). Selection of key health domains from PROMIS® for a generic preference-based scoring system. Quality of Life Research, 26, 3377–3385.

Hanmer, J., Feeny, D., Fischoff, B., Hays, R. D., Hess, R., Pilkonis, P., et al. (2015). The PROMIS of QALYs. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13, 122.

Quan, H., Sundararajan, V., Halfon, P., Fong, A., Burnand, B., Luthi, J. C., Saunders, L. D., Beck, C. A., Feasby, T. E., & Ghali, W. A. (2005). Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical Care, 43(11), 1130–1139. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83.

Funding

Funded by the National Institute on Aging (contract #HHSN271201500064C NIH NIA, PI: Edelen). The funder had no role in data collection, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript drafting, manuscript revision, or decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Approved by the Human Subjects Research Protection Committee of the RAND Corporation and the Institutional Review Board of Kaiser Permanente Colorado. The authors declare that this study was conducted in accordance with appropriate ethical standards for research, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Participants provided informed consent, with a waiver of documentation of informed consent.

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix 1: Conditions used in this study

See Table 5.

Development of code list

To develop an appropriate list of codes for the present study, we started with a set of codes developed by Quan et al., which were based on those originally established by Elixhauser for risk adjustment of chronic conditions [29]. We further modified the Quan set of codes in consultation with clinically trained members of our team and other practicing clinicians at RAND.

We modified the Quan set of codes in two main ways. First, we added codes to capture some conditions that were not included by Quan. The purpose of risk adjustment models such as the Elixhauser/Quan model is to detect chronic conditions that drive hospitalizations, costs, or mortality. Our purpose here, in contrast, was to detect conditions that would have an important effect on HRQoL. We therefore added codes to the Quan set to capture certain conditions that can impact HRQoL but are not a major cause of hospitalization or death, such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and sciatica.

Second, we added codes to extend the spectrum of disease for some conditions that were already part of the Quan model, because the spectrum of disease that we needed to detect was different. Quan was interested in detecting only the most severe manifestations of disease, because these tend to drive morbidity and mortality. For our study, we were also interested in capturing less severe manifestations of disease, because those can impact HRQoL as well. For ischemic heart disease, for example, we added the codes for angina pectoris to the codes that Quan had used to capture more severe manifestations of disease, such as myocardial infarction. We reasoned that, although angina pectoris is less severe, it could still meaningfully impact HRQoL.

Appendix 2: Comparison of survey responders with non-responders based on data derived from the KPCO electronic medical record

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, W., Rose, A.J., Bayliss, E. et al. Adapting summary scores for the PROMIS-29 v2.0 for use among older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Qual Life Res 28, 199–210 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1988-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1988-z