Abstract

Background and objective

The EuroQol 5 dimensions 5 levels (EQ–5D–5L) is the new version of EQ–5D, developed to improve its discriminatory capacity. This study aims to evaluate the construct validity of the Spanish version and provide index and dimension population-based reference norms for the new EQ–5D–5L.

Methods

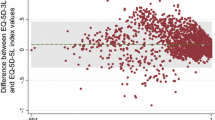

Data were obtained from the 2011/2012 Spanish National Health Survey, with a representative sample (n = 20,587) of non-institutionalized Spanish adults (≥ 18 years). The EQ–5D–5L index was calculated by using the Spanish value set. Construct validity was evaluated by comparing known groups with estimators obtained through regression models, adjusted by age and gender. Sampling weights were applied to restore the representativeness of the sample and to calculate the norms stratified by gender and age groups. We calculated the percentages and standard errors of dimensions, and the deciles, percentiles 5 and 95, means, and 95% confidence intervals of the health index.

Results

All the hypotheses established a priori for known groups were confirmed (P < 0.001). The EQ–5D–5L index indicated worse health in groups with lower education level (from 0.94 to 0.87), higher number of chronic conditions (0.96–0.79), probable psychiatric disorder (0.94 vs 0.80), strong limitations (0.96–0.46), higher number of days of restriction (0.93–0.64) or confinement to bed (0.92–0.49), and hospitalized in the previous 12 months (0.92 vs 0.81).

Conclusions

The EQ–5D–5L is a valid instrument to measure perceived health in the Spanish-speaking population. The representative population-based norms provided here will help improve the interpretation of results obtained with the new EQ–5D–5L.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The Spanish National Health Survey is an official statistic included in the National Statistical Plan. The agency responsible for the survey is the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. The anonymized microdata of the Spanish National Health Survey can be requested for purposes of scientific research.

References

Mishoe, S. C., & Maclean, J. R. (2001). Assessment of health-related quality of life. Respiratory Care, 46, 1236–1257.

Vodicka, E., Kim, K., Devine, E. B., Gnanasakthy, A., Scoggins, J. F., & Patrick, D. L. (2015). Inclusion of patient-reported outcome measures in registered clinical trials: Evidence from ClinicalTrials.gov (2007–2013). Contemporary Clinical Trials, 43, 1–9.

Brooks, R., & The EuroQol Group (1996). EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy, 37, 53–72.

Bharmal, M., & Thomas, J. III (2006). Comparing the EQ-5D and the SF-6D descriptive systems to assess their ceiling effects in the US general population. Value in Health, 9, 262–271.

Hinz, A., Klaiberg, A., Brahler, E., & Konig, H. H. (2006). The Quality of Life Questionnaire EQ-5D: Modelling and norm values for the general population. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 56, 42–48.

Xin, Y., & McIntosh, E. (2017). Assessment of the construct validity and responsiveness of preference-based quality of life measures in people with Parkinson’s: A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 26, 1–23.

Fransen, M., & Edmonds, J. (1999). Reliability and validity of the EuroQol in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology, 38, 807–813.

Krahn, M., Bremner, K. E., Tomlinson, G., Ritvo, P., Irvine, J., & Naglie, G. (2007). Responsiveness of disease-specific and generic utility instruments in prostate cancer patients. Quality of Life Research, 16, 509–522.

Janssen, M. F., Birnie, E., Haagsma, J. A., & Bonsel, G. J. (2008). Comparing the standard EQ-5D three-level system with a five-level version. Value in Health, 11, 275–284.

Feng, Y., Devlin, N., & Herdman, M. (2015). Assessing the health of the general population in England: How do the three- and five-level versions of EQ-5D compare? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13, 171.

Janssen, M. F., Pickard, A. S., Golicki, D., Gudex, C., Niewada, M., Scalone, L., et al. (2013). Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: A multi-country study. Quality of Life Research, 22, 1717–1727.

Kim, S. H., Kim, H. J., Lee, S. I., & Jo, M. W. (2012). Comparing the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L in cancer patients in Korea. Quality of Life Research, 21, 1065–1073.

Pickard, A. S., De Leon, M. C., Kohlmann, T., Cella, D., & Rosenbloom, S. (2007). Psychometric comparison of the standard EQ-5D to a 5 level version in cancer patients. Medical Care, 45, 259–263.

Jia, Y. X., Cui, F. Q., Li, L., Zhang, D. L., Zhang, G. M., Wang, F. Z., et al. (2014). Comparison between the EQ-5D-5L and the EQ-5D-3L in patients with hepatitis B. Quality of Life Research, 23, 2355–2363.

Kim, T. H., Jo, M. W., Lee, S. I., Kim, S. H., & Chung, S. M. (2013). Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in the general population of South Korea. Quality of Life Research, 22, 2245–2253.

Scalone, L., Ciampichini, R., Fagiuoli, S., Gardini, I., Fusco, F., Gaeta, L., et al. (2013). Comparing the performance of the standard EQ-5D 3L with the new version EQ-5D 5L in patients with chronic hepatic diseases. Quality of Life Research, 22, 1707–1716.

Cunillera, O., Tresserras, R., Rajmil, L., Vilagut, G., Brugulat, P., Herdman, M., et al. (2010). Discriminative capacity of the EQ-5D, SF-6D, and SF-12 as measures of health status in population health survey. Quality of Life Research, 19, 853–864.

Janssen, M. F., Bonsel, G. J., & Luo, N. (2018). Is EQ-5D-5L better than EQ-5D-3L? A head-to-head comparison of descriptive systems and value sets from seven countries. Pharmacoeconomics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0623-8.

Aaronson, N., Alonso, J., Burnam, A., Lohr, K. N., Patrick, D. L., Perrin, E., et al. (2002). Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Quality of Life Research, 11, 193–205.

Alonso, J., Regidor, E., Barrio, G., Prieto, L., Rodriguez, C., & de la Fuente, L (1998). Population reference values of the Spanish version of the Health Questionnaire SF-36. Medicina Clinica, 111, 410–416.

Vilagut, G., Valderas, J. M., Ferrer, M., Garin, O., Lopez-Garcia, E., & Alonso, J. (2008). Interpretation of SF-36 and SF-12 questionnaires in Spain: Physical and mental components. Medicina Clinica, 130, 726–735.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Herdman, M., Devine, J., Otto, C., Bullinger, M., Rose, M., et al. (2014). The European KIDSCREEN approach to measure quality of life and well-being in children: Development, current application, and future advances. Quality of Life Research, 23, 791–803.

Schmidt, S., & Pardo, Y. (2014). Normative data. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 4375–4379). Dordrecht: Springer.

Szende, A., Janssen, B., & Cabases, J. (2014). Self-reported population health: An international perspective based on EQ-5D. Dordrecht: SpringerOpen.

Konig, H. H., Bernert, S., Angermeyer, M. C., Matschinger, H., Martinez, M., Vilagut, G., et al. (2009). Comparison of population health status in six european countries: Results of a representative survey using the EQ-5D questionnaire. Medical Care, 47, 255–261.

Garcia-Gordillo, M. A., Adsuar, J. C., & Olivares, P. R. (2016). Normative values of EQ-5D-5L: In a Spanish representative population sample from Spanish Health Survey, 2011. Quality of Life Research, 25, 1313–1321.

Ramos-Goñi, J. M., Craig, B. M., Oppe, M., Ramallo-Fariña, Y., Pinto-Prades, J. L., Luo, N., et al. (2018). Handling data quality issues to estimate the Spanish EQ-5D-5L value set using a hybrid interval regression approach. Value in Health, 21(5), 596–604.

Martin-Fernandez, J., Ariza-Cardiel, G., Polentinos-Castro, E., Sanz-Cuesta, T., Sarria-Santamera, A., & Del Cura-Gonzalez, I. (2017). Explaining differences in perceived health-related quality of life: A study within the Spanish population. Gaceta Sanitaria. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.05.016.

Ministerio de Sanidad, S.S.e.I., & Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2012). Encuesta Nacional de Salud de España 2011/12. http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/encuesta2011.htm.

Herdman, M., Gudex, C., Lloyd, A., Janssen, M., Kind, P., Parkin, D., et al. (2011). Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research, 20, 1727–1736.

Oppe, M., Devlin, N. J., van Hout, B., Krabbe, P. F., & de Charro, F. (2014). A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value in Health, 17, 445–453.

Oppe, M., Rand-Hendriksen, K., Shah, K., Ramos-Goni, J. M., & Luo, N. (2016). EuroQol protocols for time trade-off valuation of health outcomes. Pharmacoeconomics, 34, 993–1004.

Gispert, R., Rajmil, L., Schiaffino, A., & Herdman, M. (2003). Sociodemographic and health-related correlates of psychiatric distress in a general population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38, 677–683.

Goldberg, D. P., & Williams, P. (1988). A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. London: Institute of Psychiatry.

van Oyen, H., Van der Heyden, J., Perenboom, R., & Jagger, C. (2006). Monitoring population disability: Evaluation of a new Global Activity Limitation Indicator (GALI). Sozial-Und Praventivmedizin, 51, 153–161.

Schmidt, S., Vilagut, G., Garin, O., Cunillera, O., Tresserras, R., Brugulat, P., et al. (2012). Reference guidelines for the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey version 2 based on the Catalan general population. Medicina Clinica, 139, 613–625.

McClure, N. S., Sayah, F. A., Xie, F., Luo, N., & Johnson, J. A. (2017). Instrument-defined estimates of the minimally important difference for EQ-5D-5L index scores. Value in Health, 20, 644–650.

Hopman, W. M., Towheed, T., Anastassiades, T., Tenenhouse, A., Poliquin, S., Berger, C., et al. (2000). Canadian normative data for the SF-36 health survey. Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research Group. CMAJ, 163, 265–271.

Burstrom, K., Johannesson, M., & Diderichsen, F. (2001). Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Quality of Life Research, 10, 621–635.

Michelson, H., Bolund, C., Nilsson, B., & Brandberg, Y. (2000). Health-related quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30—Reference values from a large sample of Swedish population. Acta Oncologica, 39, 477–484.

Power, M., Quinn, K., & Schmidt, S. (2005). Development of the WHOQOL-old module. Quality of Life Research, 14, 2197–2214.

Hinz, A., Kohlmann, T., Stobel-Richter, Y., Zenger, M., & Brahler, E. (2014). The quality of life questionnaire EQ-5D-5L: Psychometric properties and normative values for the general German population. Quality of Life Research, 23, 443–447.

Craig, B. M., Pickard, A. S., & Lubetkin, E. I. (2014). Health problems are more common, but less severe when measured using newer EQ-5D versions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67, 93–99.

Golicki, D., & Niewada, M. (2017). EQ-5D-5L Polish population norms. Archives of Medical Science, 13, 191–200.

Burstrom, K., Johannesson, M., & Rehnberg, C. (2007). Deteriorating health status in Stockholm 1998–2002: Results from repeated population surveys using the EQ-5D. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1547–1553.

Badia, X., Schiaffino, A., Alonso, J., & Herdman, M. (1998). Using the EuroQoI 5-D in the Catalan general population: Feasibility and construct validity. Quality of Life Research, 7, 311–322.

Puhan, M. A., Ahuja, A., Van Natta, M. L., Ackatz, L. E., & Meinert, C. (2011). Interviewer versus self-administered health-related quality of life questionnaires—Does it matter? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9, 30.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Aurea Martin for helping us in the English editing process and supervision of this manuscript.

Funding

This study has been funded by grants from the Generalitat de Catalunya (2017 SGR 452 and 2014 SGR 748) and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III FEDER, (PI12/00772).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GH analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted, and critically revised the manuscript and did the statistical analysis. OG provided supervision, conceived, and designed the study, and critically revised the manuscript. YP and GV analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript. AP analyzed and interpreted the data, and did the statistical analysis. MS, MN, LR, IG, YR, and JC interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. JA provided supervision, conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript. MF obtained funding, provided supervision, conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Spanish National Health Survey is a statistical operation included in the National Statistical Plan. The agency responsible for the survey is the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality and it is performed jointly with the National Statistics Institute according to the 2000 revision of the Helsinki Declaration.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernandez, G., Garin, O., Pardo, Y. et al. Validity of the EQ–5D–5L and reference norms for the Spanish population. Qual Life Res 27, 2337–2348 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1877-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1877-5