Abstract

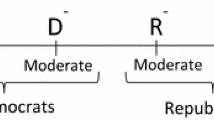

We present a formal model of intra-party politics to explain candidate selection within political parties. We think of parties as heterogeneous groups of individuals who aim to implement a set of policies but who differ in their priorities. When party heterogeneity is too great, parties are in danger of splitting into smaller yet more homogeneous political groups. In this context we argue that primaries can have a unifying role if the party elite cannot commit to policy concessions. Our model shows how three factors interact to create incentives for the adoption of primary elections, namely (1) the alignment in the preferred policies of various factions within a party, (2) the relative weight of each of these factions and (3) the electoral system. We discuss the existing empirical literature and demonstrate how existing studies can be improved in light of our theoretical predictions to provide a new, structured perspective on the adoption of primary elections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For an early discussion see, for example, North and Weingast (1989).

Boix and Svolik (2013) argue that institutionalized power-sharing within dictatorships could follow a similar logic.

Lee et al. (2004) argue that citizen candidate models account better for what actually happens in elections than Downsian models. Put differently, parties select candidates that implement their own preferred policy instead of selecting policies that are implemented by their candidates.

The rationale behind this simplifying assumption is that, relative to other selection methods, primaries have the tendency to take power away from the party elite.

In Sect. 5 we show the robustness of our results when considering a one-dimensional policy space.

The probabilities of winning the election capture a large set of models we might have in mind. For example, it could be the case that when the party splits, its voters perfectly coordinate by voting for one of the factions in order to avoid a large gain by the opposing party.

A possible example is the presence of a non-democratically elected elite that has been in power for many years while the policy preference of the party’s core supporters has shifted. The socialist party in Spain (PSOE) was, until the last leadership change in July 2014, an example of such a situation.

In order to illustrate the proposition’s result, it is best to write the two conditions in terms of y. They read as follows: \(y\; < \;\frac{1 - \alpha x}{1 - x}\;and\;y\; < \;\frac{(\alpha - 1)x}{1 - x}.\)

Their measure of this divergence is the difference between the Berry state citizen ideology score (a weighted average of the Democrat and Republican representatives’ scores) and the Berry-based Democratic elite ideology score.

In their cross-country section, Kemahlioglu et al. (2009) code the thresholds for preventing runoff elections as zero, one and two respectively. A higher likelihood of a runoff can be interpreted as a lower α and our theory suggests a non-monotonic effect on the aggregate use of primaries. However, their empirical design treats the effect of this variable as monotonic and finds no significant impact on the use of primaries. Instead, they find a negative relationship when bunching the values of zero and one and comparing them with two. Our theory suggests that this finding should become stronger when comparing the values of one and two, and weaker or even opposite between zero and one.

For instance, see Obler (2009) for a discussion of primary elections in Belgium.

Empirically this seems to be the case; see Lee et al. (2004).

A future avenue of research could analyze further the institutionalization of primaries as a more irreversible change than a policy concession. This establishes an interesting link to the work of Levy (2004), who models parties as commitment devices.

See Acemoglu and Robinson (2005) for an analogous discussion.

That this effect is not unrealistic is shown by Obler (2009) in his analysis of the introduction of primaries in Belgium. Obler argues that the Christian Social Party did not adopt primaries when the elite perceived the likely winner of the primaries to be more extreme.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2005). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Adams, J., & Merrill, S. (2008). Candidate and party strategies in two-stage elections beginning with a primary. American Journal of Political Science, 52(2), 344–359.

Aldrich, J. (1995). Why parties? the origin and transformation of political parties in America (p. 1995). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ansolabehere, S., Hirano, S., & Snyder, J. (2006). What did the direct primary do to party loyalty in Congress? In D. Brady & M. D. McCubbins (Eds.), Process, party and policy making: Further new perspectives on the history of Congress. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Aragon, F. (2009). Candidate nomination procedures and political selection: Evidence from Latin American parties, LSE STICERD Research Paper No. EOPP003.

Besley, T. (2005). Political selection. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(3), 43–60.

Boix, C., & Svolik, M. (2013). The foundations of limited authoritarian government: Institutions, commitment, and power-sharing in dictatorships. Journal of Politics, 75, 300–316.

Caillaud, B., & Tirole, J. (2002). Parties as political intermediaries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1453–1489.

Carey, J. (2003). Presidentialism and representative institutions in Latin America at the turn of the century. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Carey, J., & Polga-Hecimovich, J. (2006). Primary elections and candidate strength in Latin America. The Journal of Politics, 68(3), 530–543.

Cox, G. (1997). Making Votes Count. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crutzen, B., Castanheira, M., & Sahuguet, N. (2009). Party organization and electoral competition. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 26(2), 212–242.

De Luca, M., Jones, P., & Tula, M. (2002). Back rooms or ballot boxes?: candidate nomination in Argentina. Comparative Political Studies, 35(4), 413–436.

Folke, O., Persson, T., & Rickne, J. (2014). Preferential voting, accountability and promotions into political power: Evidence from Sweden. Huntingdon: Mimeo.

Gerber, E., & Morton, R. (1998). Primary election systems and representation. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 14, 304–324.

Hirano, S., & Snyder, J. M. (2008). The decline of third-party voting in the United States. The Journal of Politics, 69(01), 1–16.

Jackson, M., Mathevet, L. & Mattes, K. (2007). Nomination processes and policy outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 2, 67–94.

Kemahlioglu, O., Weitz-Shapiro, R., & Hirano, S. (2009). Why primaries in Latin American presidential elections? The Journal of Politics, 71(01), 339–352.

Key, V. O. (1949). Southern politics in state and nation. New York: Knopf.

Laver, M., & Sergenti, E. (2010). Party competition: an agent-based model. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lee, D., Moretti, E., & Butler, M. (2004). Do voters affect or elect policies? evidence from the U. S. House. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 807–859.

Levy, G. (2004). A model of political parties. Journal of Economic Theory, 115(2), 250–277.

Meinke, S., Staton, J., & Wuhs, S. (2010). State delegate selection rules for presidential nominations, 1972–2000. The Journal of Politics, 68(1), 180–193.

Mutlu-Eren, H. (2011). Keeping the party together. Mimeo.

North, D., & Weingast, B. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: the evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. Journal of Economic History, 49, 803–832.

Obler, J. (2009). Intraparty democracy and the selection of parliamentary candidates: the Belgian case. British Journal of Political Science, 4(02), 163–185.

Roemer, J. (2001). The democratic political economy of progressive income taxation. Econometrica, 67(1), 1–19.

Serra, G. (2011). Why primaries ? The party’s tradeoff between policy and valence. The Journal of Theoretical Politics, 23, 21–51.

Serra, G. (2013). when will incumbents avoid a primary challenge? Aggregation of partial information about candidates’ valence. In N. Schofield, G. Caballero, & D. Kselman (Eds.), Advances in Political Economy: Institutions, Modeling and Empirical Analysis (pp. 217–248). Heidelberg: Springer.

Snyder, J., & Ting, M. (2011). Electoral selection with parties and primaries. American Journal of Political Science, 55, 781–795.

Taagepera, R., & Shugart, M. (1989). Seats and votes: The effects and determinants of electoral systems. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 22, 875–876.

Tufte, E. (1973). The relationship between seats and votes in two-party systems. The American Political Science Review, 67(2), 540–544.

Ware, A. (2002). The American direct primary: Party institutionalization and transformation in the North. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Ansolabehere, Fernando Aragon, Torun Dewan, Simon Hix, Michael Laver, Massimo Morelli, Hande Mutlu-Eren, Gilles Serra, Kenneth Shepsle, participants of the APSA 2010 Annual Meetings and seminar participants at the London School of Economics and Universitat Autonoma of Barcelona for helpful comments and discussions. Hannes Mueller acknowledges financial support by the Juan de la Cierva programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hortala-Vallve, R., Mueller, H. Primaries: the unifying force. Public Choice 163, 289–305 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0249-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0249-8