Abstract

This theoretical review proposes an integrated biopsychosocial model for stress recovery, highlighting the interconnectedness of intra- and interpersonal coping processes. The proposed model is conceptually derived from prior research examining interpersonal dynamics in the context of stressor-related disorders, and it highlights interconnections between relational partner dynamics, perceived self-efficacy, self-discovery, and biological stress responsivity during posttraumatic recovery. Intra- and interpersonal processes are discussed in the context of pre-, peri-, and post-trauma stress vulnerability as ongoing transactions occurring within the individual and between the individual and their environment. The importance of adopting an integrated model for future traumatic stress research is discussed. Potential applications of the model to behavioral interventions are also reviewed, noting the need for more detailed assessments of relational dynamics and therapeutic change mechanisms to determine how relational partners can most effectively contribute to stress recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social support is well-established as a major protective factor following potentially traumatic events (i.e., exposure to “death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence”) [1]. Social support has demonstrated numerous protective effects, from buffering risk for negative psychological outcomes (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD; depression; self-harm) [2,3,4] to enhancing treatment (i.e., quicker reductions in PTSD symptoms, lower rates of PTSD symptom recurrence) [5, 6]. These protective effects can manifest from various types of social relationships (e.g., romantic partners, family members, close friends) and shield against mental health problems stemming from multiple forms of trauma (e.g., combat, assault/abuse, witnessed violence, traumatic loss, natural disasters) [7,8,9,10,11].

However, the functions of social relationships are nuanced, and an established body of research has worked to identify exactly how social support mitigates psychological symptoms and functional impairment after trauma. Some of this work has focused on better understanding how nuanced, contextualized effects and interpersonal processes within certain relationships (e.g., relational qualities) may promote post-trauma resilience and recovery [12, 13]. Other work has emphasized the need to understand sociocultural influences on posttraumatic stress recovery in the context of evolutionary and psychobiological theoretical frameworks [14, 15].

Given the varied pathways by which individuals eventuate in similar (i.e., equifinality) and divergent outcomes (i.e., multifinality) following traumatic stress exposure, the field would benefit from a comprehensive conceptual model [16, 17]. A unified framework that merges theoretical perspectives and empirical research on biological and cognitive stress response systems may encourage and guide multilevel and multimodal examinations of biological, cognitive, and social processes that collectively contribute to resilience and recovery following a potentially traumatic event. The introduction of such a framework is timely given how the recent widespread global CoVID-19 pandemic has increased awareness of the varied ways in which social processes can both increase (e.g., isolation, loneness) and buffer (e.g., social support, shared experience) risk for poor mental health outcomes following traumatic stress exposure [18].

We propose the Integrated Biopsychosocial Model for Posttraumatic Stress Recovery (IBM-PSR) as a framework for understanding stress recovery in the interpersonal context following trauma exposure. This framework considers intrapersonal coping (i.e., internal resources and strategies, such as schema change, that contribute to the stress response) [19] as inextricable from interpersonal coping (i.e., external resources, such as social support and relational dynamics, that contribute to post-stressor recovery) [20, 21]. As such, the IBM-PSR considers the adaptive and maladaptive mechanisms through which relational partners influence the posttraumatic stress response as being co-determined by ongoing intra- and inter-personal coping processes. The framework also highlights the impact of trauma on the biopsychosocial foundations of social support, which connect posttraumatic adjustment with biological stress response system functioning, altered perceptions of self-efficacy, and functional, coping-centric aspects of social support. Following the presentation of the IBM-PSR, we discuss implications of this integrated framework for research and behavioral intervention efforts.

The Integrated Biopsychosocial Model for Posttraumatic Stress Recovery

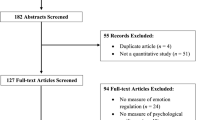

The IBM-PSR assimilates the fundamental components of well-established theory in a unified framework that summarizes specific processes contributing to posttraumatic stress recovery in the interpersonal context (see Fig. 1). Posttraumatic stress recovery is a dynamic process involving transactions between biological and cognitive stress responses [14]. As such, the IBM-PSR presents inter- and intrapersonal coping strategies in the context of continuous, transactional, biopsychosocial processes inherent to an individual’s intrinsic traumatic stress responses and recovery.

Instead of viewing trauma as an insular mechanism, diathesis-stress frameworks assert that stressors are merely catalysts that prompt psychological reactions, which are governed by several pre-, peri-, and post-trauma susceptibility factors [22, 23]. These vulnerabilities have been conceptually divided into ecological diatheses (i.e., encompassing the self and environment), biological diatheses (e.g., genetic, neurological features), and catalyzing factors (e.g., trauma-related variables, residual stress [22]. Within a diathesis-stress framework, ecological predispositions (e.g., individual’s developmental history and coping style) and biological predispositions (e.g., threat-response neural circuitry) interact with pathogenic triggers (e.g., trauma) to initiate a psychological stress reaction that can spur recovery or contribute to dysregulation and the emergence of psychopathology. The tenets of the diathesis-stress framework are used to organize the other major theoretical perspectives and domains of research that are referenced throughout presentation of the IBM-PSR.

The role of relational partners in providing social support is highlighted specifically in the posttraumatic stress recovery period and depicted as “Interpersonal Coping” in Fig. 1. Interpersonal coping is defined as any post-stressor behavior that centers on use of social relationships to facilitate recovery. Intrapersonal coping is presented as any self-initiated, post-stressor behavior enacted with the intention of facilitating recovery of the intrinsic stress response. By considering multiple, multilevel risk factors and pathogenic mechanisms, the IBM-PSR aims to provide a guiding model for understanding variance in posttraumatic recovery and explaining why some individuals develop significant mental health symptoms whereas others experience resilience and growth.

The full IBM-PSR conceptual model is discussed below. Discussions of relevant theory and empirical findings are intentionally succinct to maintain focus on the overarching model.

Latent Stress Response

The processing of an acute traumatic event is influenced substantially by cognitive and biological dispositions (i.e., endogenous, intrinsic factors) prior to the trauma, referred to herein as the “latent stress response” (referred to in other work as a component of “pre-traumatic factors”) [24, 25]. Some individuals may have intrinsic factors that predispose them to respond adaptively post-stressor. Other individuals may have cognitive and biological dispositions that have been taxed by historical or co-occurring stressors, which may potentiate vulnerability for PTSD.

Paths A and B

The cognitive and biological components of the latent stress response work in a synergistic and dynamic fashion to set the stage for an individual’s reactions to a potentially traumatic event. In line with the social cognitive theory for posttraumatic recovery [26], the cognitive component of the latent stress response consists of social-cognitive schemas that represent the individual and their world. Cognitive disposition and biological stress response proclivities within the latent stress response reciprocally influence one another [14], such that cognitive schemas resulting from an individual’s past encounters with stressors influence the disposition of biological stress response systems (path A), which in turn influence cognitive disposition through neurocognitive functioning and biofeedback (path B). For example, an individual may be predisposed to experience exaggerated biological reactivity in response to a new stressor if the schema that informs their appraisal of a stressor is rooted in prior failed attempts to cope with similar stressors. Biological factors such as poor diet, excessively low/high activity levels, abnormal circadian rhythm, and physical illness also contribute to overall stress vulnerability [27].

Path C

Consistent with bioecological systems [28] and biopsychosocial-evolutionary frameworks [14], bidirectional associations exist between an individual’s stress response system (i.e., latent, acute, recovery) and the environment. That is, factors within the environment (e.g., financial, interpersonal, cultural) [25] contribute to an individual’s latent stress response [29, 30], which in turn, can affect interactions with their environment. As suggested by the stress generation hypothesis [31], individuals exposed to substantial stressors in their environment may develop negative cognitive styles and dysregulated affective states and, as a result, select into or contribute to challenging environmental contexts. This hypothesized transaction has been documented in particular for individuals living in low-income and impoverished communities [32], with poverty-related stressors and racial marginalization contributing to dysregulated biological and cognitive predispositions that manifest in future stress management difficulties [33, 34]. The IBM-PSR posits that the bidirectional relationship between an individual’s intrinsic disposition and the environment (e.g., financial, cultural) is continually present within every phase of the posttraumatic stress response process, as denoted by all paths labeled C in Fig. 1. Given the focus of the current framework on interpersonal processes during posttraumatic recovery, transactions between the individual and the environment during the recovery phase are parsed more fully below (paths L-Q).

Acute Stress Response

Paths D, E, F, and G

The latent stress response influences the acute stress response in the face of a stressful event, as predisposing cognitive schemas are applied when appraising the level of threat presented by a current stressor (path D) [35]. Research in affective neuroscience suggests that preconceptions of threat/injury and self-efficacy are embedded in memory with affective cues that actuate biological stress responses accordingly in potentially harmful situations (path E) [36]. As such, pre-established schemas not only impact the evaluation of a future or current stressor, but also the degree to which biological stress response systems become activated in response to the stressor. Historical and co-occurring stressors also contribute to allostatic load – the cumulative toll of chronic or significant stressors on physiologic stress response systems [37]. Individuals with high allostatic load often show impaired and discordant functioning across multiple, interconnected biological stress response systems implicated in stress response and recovery. For instance, high allostatic load can contribute to sustained physiological arousal, systemic inflammation, dysregulated neuroendocrine function, aberrant brain connectivity, and adverse gene expression [38,39,40,41]. Baseline biological stress response systems affected by prior stressors influence both perceptions of threat (path F) and how strongly the biological stress response system will react to perceived danger (path G). Individuals experiencing a heightened state of biological stress vulnerability are more likely to perceive an event as dangerous and experience more significant biological stress reactions [37].

Paths H and I

In the face of an acute stressor, cognitive and biological response processes influence one another in a reciprocal manner. As perceptions of danger increase and self-efficacy decreases, biological stress response systems are more likely to increase in activation (path H). In turn, increased activation provides physiological feedback that may increase perceptions of danger (path I). In other words, the more a person perceives danger, the more they feel stressed; and the more stressed a person feels, the more they perceive danger. In some situations, conscious cognitive evaluation of situational stressors may initiate a stress response. However, the “sudden” nature of trauma may lend itself more to involuntary stress responses that involve a greater degree of rapid subconscious processing reliant on pre-established schema.

Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Coping

Paths J and K

Strategies for intrapersonal coping are directly influenced by acute cognitive and biological stress responses, with indirect effects derived from latent responses. At the cognitive level, appraisals of stress and self-efficacy inform the individual’s assessment and execution of intrapersonal coping strategies (path J) [19, 26]. The dynamic tension between initial threat and self-efficacy appraisal processes involves ongoing individual-environment transactions that unfold in the moment and eventuate in the individual’s response to the stressor [19, 42, 43]. Thus, appraisal processes can recursively influence an individual’s response to trauma reminders and subsequent stressor exposures. During the recovery phase, election of coping strategies is focused on maximizing self-efficacy. Self-efficacious individuals may implement a wide range of active intrapersonal coping strategies: cognitive restructuring (i.e., modifying appraisals of stressful events and one’s ability to cope), emotion regulation, problem solving, and proactive reduction in stress vulnerability (i.e., reducing factors that influence overall stress levels such as financial problems, health conditions, and poor self-care [44, 45]. Coping research within the PTSD literature corroborates the importance of coping self-efficacy, showing that self-efficacious individuals who frequently use active, agentic intrapersonal coping skills show greater rates of posttraumatic recovery than those who do not [46]. Moreover, greater flexibility in utilizing active coping strategies has been shown to reduce the risk of PTSD following trauma [47].

Self-efficacy may be lower for novel trauma and also for trauma that bears strong similarity to stressful events that an individual had difficulty managing in the past. In these situations, the individual may need to explore new coping responses and seek out higher levels of social support to cope adaptively. Otherwise, the individual may resort to ineffective and iatrogenic coping behaviors, such as repressing undesirable aspects of the situation (avoidance), adjusting goals to better align with the situation (accommodation), or viewing their coping response to the situation as unimportant (devaluation) [48]. Less agentic forms of coping, such as these, maintain or amplify traumatic stress reactions and contribute to PTSD symptoms [49].

At the biological level, the selection and effective enactment of a coping response is supported by physiological resource mobilization and regulation of biological stress responses (path K) [50]. Unfortunately, traumatic stress exposure can adversely impact neurobiological systems needed to cope effectively. A full review of biological factors contributing to posttraumatic stress recovery is beyond our purview, but we briefly mention them here to note the importance of considering the complex and dynamic interactions that occur within and between biological systems affected by trauma exposure as contributors to one’s coping capabilities [14]. The Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) axis has been investigated extensively and shown to play a key role in trauma-related symptom emergence and maintenance [51, 52]. Individuals suffering from PTSD show dysregulated patterns of HPA activity throughout the day (i.e., diurnal fluctuations), compared to individuals who have not been exposed to trauma [53]. In addition, those with PTSD are known to exhibit a dysregulated HPA axis response to acute stressors (e.g., hypoactivation, hyperactivation) [53]. HPA hypoactivation fails to mobilize biological resources requisite for generating appropriate behavioral responses to manage acute stressors. Alternatively, HPA hyperactivation involves activation that exceeds what is warranted by the stressor, which cognitively incapacitates individuals and inhibits efficient use of executive resources for effective stressor management (e.g., regulatory interference) [54]. Overexposure to glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) that accompanies HPA hyperactivation is known to have neurotoxic effects brain regions implicated in affect regulation and executive functions (e.g., ventromedial prefrontal cortex) [55]. These findings are consonant with a burgeoning literature linking stressor exposure, acute and diurnal HPA dysregulation, and impaired prefrontal executive functioning (e.g., working memory, cognitive flexibility) involved in active coping (e.g., problem solving, cognitive restructuring) [56].

HPA dysregulation provides only one example of how trauma-related impairment of executive control, mediated by neurobiological disturbance, can compromise agency and ability to actively and effectively cope with stressors. Researchers have identified, and continue to identify, a variety of biological systems affected by trauma and biological mechanisms contributing to stress-related risk and resilience [22, 57, 58]. These include genetic and epigenetic factors, and their mediating relations with endophenotypes [59], levels of inflammatory markers [60], stress-reactivity neuroendocrine profiles (e.g., glucocorticoids, androgens) [51, 52], aberrant brain function and structure [61], and key regulators of sympathetic arousal and parasympathetic recovery, such as endogenous neurochemicals (e.g., norepinephrine, epinephrine, GABA) [62] and exogenous agents (e.g., propanalol) [63].

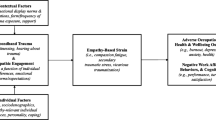

For individuals exhibiting an exaggerated biological reaction to trauma, behavioral responses may be characterized by psychobiological paralysis (i.e., freezing behavior), poor execution of active coping skills (e.g., problem solving), or more automatic, involuntary responses (e.g., aggression, avoidance, fight or flight) focused on quickly neutralizing the stressor. Such behavioral responses may lead to poor resolution of stress or even amplification of an individual’s trauma response (i.e., make the situation worse and cause further emotional distress). Even more, an overall pattern of stress responding can emerge whereby dysregulated biological stress responses lead to ineffective behavioral responses, which decrease perceptions of self-efficacy. In turn, decreases in self-efficacy increase the likelihood of biological dysregulation and ineffective behavioral responses (see Fig. 2 for an illustration). Should such a pattern emerge, the risk of PTSD increases significantly.

Paths L and M

Social relationships with relational partners hold the potential to positively or negatively influence intrapersonal coping processes. As such, we will forego the term social supports, in favor of the term relational partnersFootnote 1 with due acknowledgment that not all relationships and interpersonal responses are inherently supportive.

Psychobiological impairment and reductions in self-efficacy resulting from trauma often pull for support from relational partners. In turn, partners are tested in their ability to rise to the occasion and meet the supportive needs of the trauma-exposed individual. The deleterious effects of trauma on biological and cognitive systems, lowered perceptions of self-efficacy, and less effective coping may result in more frequent support-seeking behavior [64], which increases demands on relational partners, who may not be well-equipped to provide effective psychological support. Although individuals with larger social support networks typically experience fewer negative outcomes post-stressor [65], vis-à-vis stress buffering [66,67,68], more fine-grained research has suggested that the perceived helpfulness of one’s social support network is more strongly associated with posttraumatic adjustment than the size of one’s support network [69, 70]. This supports the position that functional, qualitative dimensions (i.e., emotional, instrumental) may better predict stress recovery than structural dimensions of social support (i.e., network size, frequency of social interactions [71, 72].

Social support may be offered in response to a direct or indirect solicitation for support by the stressed individual, or also based on deductive reasoning (i.e., based on the demands of the environment and known/inferred stress-managing capabilities of the individual) (path L). Trauma-exposed individuals can leverage relationships to help themselves more effectively use intrapersonal coping strategies (path M), but this assumes that relational partners’ possess the ability to offer support that aligns with the individual’s needs. The social cognitive theory for posttraumatic recovery emphasizes the connection between social support and agency, suggesting that support most effectively facilitates recovery from trauma-related stress when it enables a person to utilize existing, or develop new, intrapersonal coping skills. More self-efficacious individuals may use the relationship context as a “sounding board,” while individuals with lower self-efficacy may require more involved assistance. Social supports may promote intrapersonal coping by either encouraging the utilization of specific strategies or actively modeling such strategies. Additionally, social support can serve to decrease avoidance and encourage other proactive actions that reduce risk for PTSD [73, 74]. For example, friends or family may encourage a trauma-afflicted loved one to resume daily activities, to confront trauma reminders, to discuss and process the traumatic event and their reactions, and to implement other effective coping strategies during high-stress periods.

Consistent with current models of differential susceptibility [75], posttraumatic growth (PTG) theory proposes a qualitative shift in the operationalization of posttraumatic adjustment, from a restricted focus on the reduction of negative affect, posttraumatic distress, and related sequelae (i.e., recovery) to further include increases in positive affect, appreciation of life, spiritual enrichment, and other adaptive potentialities (i.e., growth) [76]. PTG implicates the interplay of interpersonal (e.g., self-disclosure, social support) and intrapersonal (e.g., schema change) processes in postraumatic adjustment in ways that facilitate growth (e.g., sense of personal strength). PTG deviates from social cognitive theory in two notable ways. First, in social cognitive theory, social support-driven posttraumatic adjustment is achieved vis-à-vis self-efficacy, while in PTG theory such adjustment is achieved vis-à-vis self-discovery. In other words, social cognitive theory holds that social support fosters agency through encouraging use and socialization of coping skills. PTG theory, on the other hand, holds that social support fosters actualization through interpersonal self-disclosure and discourse, such that individuals co-construct novel self-narratives as well as re-construct schemas about one’s character, meaning, and purpose. Second, in social cognitive theory, social support processes focus on remediating the individual, and once self-efficacy is bolstered and the trauma symptoms are alleviated, the individual terminates the use of support-driven coping strategies. In PTG theory, social support focuses on transcending the individual and continuing prosocial behavior-driven increases in hedonic, eudaimonic, and psychological well-being of the self-discovered individual. Posttraumatic growth (PTG) theory [76] suggests that continued dialogue with relational partners over time could aid in the generation of new self-narratives and a redefined understanding of one’s character, meaning, and purpose (e.g., a newfound belief in one’s abilities after managing reactions to traumatic event).

Relational partners who previously experienced trauma and were successful in effectively managing their posttraumatic stress reactions may prove to be a potentially important source of social support [77]. These partners may be knowledgeable about supportive strategies (e.g., emotional, instrumental) that foster adaptive intrapersonal coping. As an example, among parent–child dyads, children tend to have better psychological outcomes if their parents report lower levels of distress [78]. PTG theorists hold that stress-exposed individuals may be more willing to self-disclose to relational partners who can relate to their traumatic experiences, normalize their reactions, and assist in modifying problematic narratives and schemas about the trauma, given the credibility of their partner’s perspective [76].

Despite the best efforts of relational partners, core symptoms of PTSD can make receiving social support difficult and negatively impact social relationships. For instance, trauma-affected individuals often withdraw from others and present as angry or irritable when they are socially engaged [79, 80]. Trauma-induced deficits in problem-solving, difficulties with intimacy, and aggressive behavior may impinge on relationship quality and the likelihood of receiving future relational support [81,82,83]. Due to heightened stress levels and limited executive capacity, trauma-affected individuals may fail to attend to relational partners’ emotional state or support them in times of need, resulting in a lack or reciprocity [84]. These interpersonal difficulties often lead to increased misunderstandings in the relationship, increased conflict, and decreased relationship satisfaction, all of which reduce the likelihood of relational partners offering continued support [85]. Work examining bidirectional associations between social support and health outcomes suggests that the stress buffering effects of social support may decrease over time as stress-related psychological symptoms and increased impairment place strain on relationships, thereby dampening the availability and quality of support [21]. A recent meta-analysis found that PTSD symptoms and social support were reciprocally connected over time such that greater social support predicted decreases in PTSD symptoms and greater PTSD symptoms predicted decreases in social support, which were more significant within closer relationships (family members, significant others, friends) [86].

Other problematic interpersonal dynamics can also occur in the context of trauma recovery. Relational partners who are less efficacious in active listening, managing their own stress reactivity, tolerating others’ distress, or offering perspectives that can be incorporated into constructive schema change may be more dismissive or divert the conversation to avoid discussions about traumatic experiences (e.g., “That’s not a big deal”). Some relational partners may respond to disclosures of trauma with harmful criticism (e.g., blaming, demeaning, or teasing comments), which can promote increased negative affect, diminish perceptions of self-efficacy, and reinforce existing harmful schemas (e.g., shame, guilt, failure). A recent meta-analysis determined that trauma-exposed individuals with relational partners who show greater negative affect towards them and make more negative social evaluations of them experience more severe PTSD symptoms; in fact, the effect size for “negative social reactions” in predicting PTSD symptom severity was significantly larger than those of more positive social support factors [87]. In addition to negatively influencing an individual’s self-perceptions and serving as an additional source of stress following trauma, relational partners may model and encourage ineffective or harmful coping strategies, such as substance use, aggression towards others, or suicidal ideation [88, 89]. If relational partners actively avoid discussing traumatic events, respond punitively to disclosure, or otherwise encourage iatrogenic coping strategies, these behaviors could reinforce maladaptive coping and psychobiological dysregulation for the trauma-exposed individual, thereby increasing risk of PTSD symptoms [90, 91].

Relational partners may also provide precarious support – interpersonal behaviors that appear helpful and may offer some benefit (e.g., increased social connection, temporary distress alleviation) but may also be disadvantageous in promoting self-efficacy or self-discovery. Co-rumination, or a tendency to dwell on problems and negative affect in the interpersonal context [92], is one example of precarious support. Though examined predominantly in the depression literature, this dyadic interpersonal process has implications for posttraumatic stress recovery as well. While those who co-ruminate with a stress-exposed individual may demonstrate basic support skills such as responsiveness and validation, the process of co-rumination often fails to generate agentic ideas for adaptive coping. Thus, the trauma-affected individual may “feel” supported but remain stressed in the absence of a plan to actively manage their stress. Co-rumination may even serve as a mechanism that facilitates contagion of internalizing symptoms within relationships [93], thereby increasing risk of psychopathology for both the stressed individual and their relational partners. Of note, co-rumination is distinct from mutual cognitive processing [76], whereby relational partners engage with stress-exposed individuals in thinking that is conscious, instrumental in its focus, and not directly cued from the environment. Mutual cognitive processing can offer stress-exposed individuals additional opportunities for meaning making and positive reinterpretations of problematic trauma-related beliefs.

Other forms of precarious support may effectively reduce an individual’s stress levels in the short-term but present problems in the long-term. For instance, relational partners may directly manage or remove environmental factors that contribute to stress levels (e.g., giving money to reduce financial distress; allowing the stressed individual to stay at their home to avoid marital strife; communicating with someone on behalf of the stressed individual to avoid conflict), but not address the underlying posttraumatic stress symptoms. Notably, these partner behaviors may be vital in supporting the immediate physical safety and security of recently stress-exposed individuals. However, in the long-term (presumably when the immediate threat has passed), they may promote avoidance, diminish agency, and thwart actualization for the trauma-exposed individual. In essence, precarious support can bypass the intrapersonal processes required for helping a stress-exposed individual strengthen their own coping self-efficacy and foster their own self-discovery. As such, precarious support can foster patterns of excessive reassurance-seeking and dependency on others for stress management [94]. The resulting perpetuation of low coping self-efficacy, lack of schema reconstruction, and maintenance of elevated traumatic stress levels has the potential to strain ties with relational partners who are overly relied upon.

Certain unhelpful dynamics may be more likely to occur with relational partners who are experiencing their own posttraumatic stress reactions due to direct or vicarious trauma exposure.

When an individual and their relational partner are both experiencing psychological symptoms, a reciprocally supportive relationship could be difficult to maintain due to competing needs and the limited availability of psychological resources required to provide effective support. As an example, if a relational partner was impacted by the same trauma (e.g., family members who experienced the same home invasion or car accident) and both partners are struggling to cope, the relationship could become non-supportive. This may take the form of mutual avoidance of disclosures about the trauma (due to fears of triggering one another), co-ruminative discussions, or joint engagement in harmful avoidant coping strategies (e.g., substance use, risk-taking). Given the strain that traumatic stress can place on relationship functioning, it is not surprising that PTSD symptoms prospectively predict decreases in social support in the years following a traumatic event [21, 95, 96].

Paths N and O

Supportive behavior may also focus on making modifications to the environment that facilitate intrapersonal coping (e.g., helping the individual meet immediate physical safety and security needs, removing or reducing stressors not directly tied to the trauma) (path N). However, relational partners who continue to provide excessive reassurance and accommodations even after the threat to physical safety and security has passed may miss opportunities to promote intrapersonal coping and consequently foster dependency in the trauma-affected individual. The quality and degree of support offered may also be influenced by environmental factors affecting the relational partner (path O). For instance, a relational partner may be able to provide only limited support if they are struggling to manage their own cognitive and biological stress reactions to chronic or multiple environmental stressors.

Paths P and Q

Intrapersonal coping can modulate the potentially deleterious impact of traumatic stressors in individuals’ immediate environmental contexts (path P). Examples include an individual leaving or changing the situation (e.g., situation selection/modification) or using internal coping strategies (e.g., attentional deployment, cognitive restructuring) to reduce the influence of the environment on their ability to manage their stress response [97]. As noted by Tedechi and Calhoun [76], traumatic events happen not only to individuals, but also to relational partners, groups of people, and societies. When trauma is widespread, intrapersonal attempts at meaning-making and reconstructing narratives may generate new schemas that challenge existing social conventions (e.g., stigma) and seek to change problematic environmental structures (e.g., laws). Through transformative mutual support, stressor-exposed individuals’ narratives can be integrated into socially shared schemas. As an example, a recent study using nationally representative sample of US veterans showed that, in addition to receiving social support, increases in altruistic behavior (e.g., provision of support to those in need) reduced internalizing symptoms, perhaps by reducing social isolation and loneliness but also by promoting a sense of meaning, direction and purpose in life [77].

Environmental factors also influence an individual’s ability to cope intrapersonally (path Q), such as the continued presence of trauma cues, other environmental stressors, and accessibility of coping resources. Continued exposure to trauma cues and additional stressors could maintain or increase stress responses, thereby challenging an individual’s ability to successfully utilize intrapersonal coping strategies. Environmental responses that address the trauma directly (e.g., justice delivered by the legal system) or reduce the likelihood of similar trauma in the future (e.g., revamped community safety measures) may positively impact intrapersonal efforts and further enhance recovery. Similarly, recent work has demonstrated that social identification with one’s community, collective agency, and well-being stemming from expected support and shared goals in the wake of a common traumatic stressor can improve recovery (e.g., natural disaster) [98].

Stress Recovery

Paths R, S, T, and U

Intrapersonal coping mediates pathways from acute response to recovery through alterations in threat and injury appraisals, perceived self-efficacy, schema modification, narrative reconstruction, and regulation of biological stress response systems. Strategies that serve to change perceptions (e.g., cognitive restructuring), recalibrate biological arousal (e.g., relaxation), or modify environmental stressors (e.g., leaving the situation or making an environmental change) may all help to regulate stress responses (paths R and S) and facilitate efficient stress recovery. As perceptions of threat/injury decrease and perceptions of self-efficacy increase, biological stress vulnerability lessens (path T), and in turn, reductions in biological stress vulnerability increase appraisals of safety/wellness and self-efficacy (path U). Thus, intrapersonal and interpersonal coping contribute meaningfully to recovery through adjustments to one’s appraisals of stress and self-efficacy, schema about the trauma, and ability to regulate biological stress responses and/or change the environment.

Environment and Time

Path V

Importantly, some environmental factors contributing to an individual’s latent stress response will likely exert influence across the acute stress response and recovery phases. These ongoing environmental factors (path V) may include socioeconomic strain, maltreatment, pollutants, population density, and cultural oppression. Some environmental factors may remain consistent across each phase of the stress response (e.g., local culture) and, thus, maintain risk or promote resilience in an ongoing manner. However, as noted for paths N and P, intra- and interpersonal coping processes can also influence environmental factors and context.

Time

Time is an important concept within the recovery phase of the IBM-PSR. The timeline for recovery begins immediately following an acute traumatic experience. Importantly, we note that timelines for recovery are individual-specific, such that the length of time between the traumatic event and stress recovery is contingent on a multitude of factors, including intrinsic and learned coping abilities, as well as access to resources that support utilization of intra- and interpersonal coping strategies. Defining the end point to “recovery” is complex, given the varied indicators that could be used to operationalize recovery. For example, using “return to baseline” (biological or psychological state) assumes that baseline functioning was adaptive and healthy, and even if this assumption was upheld, “healthy” psychological functioning in the posttraumatic recovery phase may be qualitatively very different from healthy pre-trauma functioning (i.e., conceptualizations of recovery need to acknowledge posttraumatic growth).

The effectiveness of specific coping strategies in facilitating recovery may differ based on the phase of recovery (i.e., they may be time-dependent). For example, avoidance (e.g., running away) at the outset of trauma exposure (e.g., physical assault) may serve to mitigate cognitive and biological “wear and tear” that an individual might otherwise incur if they chose to remain proximal to the trauma and/or related stressors. Approach-oriented coping in the face of an immediate and uncontrollable trauma may compromise safety and psychobiological function that would otherwise have been preserved with more avoidant flight-oriented strategies. In the long-term, however, prolonged avoidance (e.g., difficulty leaving the house months after a traumatic event) may impede efficient stress recovery, whereas active coping strategies (e.g., leaving the house to run errands, returning back to work) may promote efficient stress recovery.

With regards to time-sensitive interpersonal coping, relational partners may be most helpful if they encourage the use of intrapersonal strategies that align with the phase-specific needs of the trauma-affected individual. Relational partners may help with practical challenges in the immediate aftermath of the trauma (e.g., filing a police report) and eventually transition to providing increased emotional support. Psychological First Aid [99] and Skills for Psychological Recovery [100] are trauma-centered prevention programs that emphasize the importance of tailoring support to individuals and their phase of recovery.

Recovery-informed Dispositions

Path W

The overall stress response (i.e., acute stress response plus stress recovery) to the traumatic event or trauma reminder informs the individual’s future latent stress responses as a function of altered disposition (path W). An individual’s perceived self-efficacy in managing their stress response and the impact of the stressor on their overall well-being are incorporated into social-cognitive schema. Similarly, the degree of activation caused by the stressor as well as the duration of sustained activation influences the set points for biological stress response systems, both with regard to diurnal (i.e., daily) and acute (i.e., stress-reactive) functioning.

Directions for Future Empirical Research

The literature reviewed and model proposed above underscore the need for nuanced research that addresses how interpersonal, biological, and cognitive processes operate together in governing posttraumatic stress recovery. As researchers continue to examine connections between social support and PTSD symptoms, the proposed theory could serve as a framework for identifying specific unilateral and transactional mechanisms that either confer risk or promote recovery. While social support has been widely regarded as protective, our review has illustrated that not all social support is created equal and studying the ‘who, what, when, where, and how’ of social support is critical for identifying interpersonal behaviors that promote and hinder efficacious coping following trauma. We provide recommendations for future research that may address remaining gaps in this field, emphasizing the need for multimodal, multidimensional, and prospective assessments of stress responses (latent, acute, recovery), intrapersonal and interpersonal coping processes, and environmental factors. Further, we note the importance of proper research designs and analytic techniques suitable for testing the proposed model and discuss implications of such research for prevention and intervention.

Intrapersonal Coping, Interpersonal Coping, and Post-Trauma Recovery

To adequately examine the interconnections between processes most relevant to post-trauma recovery, prospective, multimodal research designs are needed. Changes in concurrent functioning of neuroendocrine, physiological, and immunological stress response systems should be monitored simultaneously with longitudinal collection of biological samples (e.g., salivary cortisol, alpha-amylase, heart rate variability, inflammatory cytokines) to establish cross-system profiles of biological vulnerability. In particular, prospective work should aim to include experimental paradigms that examine functioning of these systems in relation to acute stress, threat, and reward (including for instance indices of cortisol reactivity, error-related negativity, reward positivity) over time and under specific conditions of intrapersonal coping (e.g., avoidance, distraction). Additionally, in vivo paradigms are needed that examine negative and positive valence systems specifically in the context of interpersonal stress processing, with consideration of varied relationship types (e.g., close friendships, romantic partnerships, caregiver-child relationships) and concomitant functioning of neurobiological systems most responsive to interpersonal processes (e.g., oxytocin system). Behavioral observation systems should examine connections of neurobiological systems with naturally-occurring interpersonal stress processing and across instructed conditions of support (e.g., active listening, validation, problem-solving, coping skills identification/expansion). Ecological momentary assessments (EMA) of coping behaviors, cognitive processes, trauma-related stressors (e.g., triggers), and posttraumatic symptoms administered in combination with the aforementioned experimental paradigms would allow for both micromomentary and situational-based examinations of trauma recovery. Extended measurement may be needed to capture growth indices (e.g., shifts in trauma-related self-perceptions/narratives) and other distal outcomes of trauma (e.g., tracking trauma-exposed children into late adolescence/adulthood to learn how early-life trauma affects relationships and mental health later in life). Data collected from multimodal, prospective research designs may benefit from use of multilevel, person-centered analyses and latent class analyses [101, 102] to identify individual differences in stress recovery processes and PTSD risk profiles that better indicate the level of intervention needed.

Intervention research specifically dedicated to the promotion of resiliency by modulating the links between social support and coping is warranted. The state of the science establishing the efficacy of trauma-related treatment across the lifespan is encouraging, with numerous randomized controlled trials demonstrating that trauma-exposed individuals with significant mental health symptoms recover with treatment [103,104,105]. Recent advances in treatment research have demonstrated that relational partners play an important role in facilitating coping skill development. For instance, incorporating a caregiver to both model and promote coping has become an important element of empirically supported treatments for youth, such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy (TF-CBT) [106] and Risk Reduction through Family Therapy (RRFT) [107]. Similarly, cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy for PTSD incorporates romantic partners to help support trauma-affected individuals in their recovery [108]. Recruiting relational partners to help provide encouragement, model coping skills, and support completion of exposure-based activities may be an effective way to increase treatment retention and positive treatment outcomes [109, 110].

However, incorporating relational partners into trauma treatment also comes with challenges. Partners may have difficulties hearing details of trauma involving gruesome injuries, death, or physical/sexual abuse, especially if they are close to a person who suffered during the trauma. These difficulties could manifest as a secondary or vicarious trauma response, which could decrease the likelihood that a trauma-affected individual will continue to process the trauma with their relational partner (i.e., promote avoidance) or reduce the quality of support received (e.g., partners struggling to manage their own reactions may not be able to provide helpful suggestions for coping). In some cases, relational partners may have experienced the same trauma and have difficulty supporting one another due to the impact of the trauma on their own stress regulating capacities. As noted earlier, posttraumatic stress and conduct problems are greater for children of caregivers who report high levels of distress after a traumatic event [78]. Carefully assessing a relational partner’s readiness to provide support is essential for minimizing any potential problems that could arise should they be included as part of treatment planning.

Finally, the IBM-PSR provides opportunities for prevention efforts examining the utility of relational partners and intrapersonal coping strategies in mitigating mental health symptoms following exposure to traumatic stressors. Over 60% of individuals have experienced one or more adverse childhood experiences [111], which suggests that a significant proportion of the population have experienced a major stressor, or several, during their lifetime. Many of these individuals do not seek formal interventions and instead rely on their own intrapersonal coping mechanisms and relational support networks. However, as previously described, even well-intentioned support efforts can fall flat or foster maladaptive coping strategies. Dismantling research is needed to determine which aspects of social support most effectively reduce the impact of traumatic stress and improve one’s capacity to cope. Specifically, research that closely examines the interpersonal components of intervention and prevention programs are needed to clarify whether providing psychoeducation about trauma and teaching constructive support (e.g., promoting self-efficacy, relaxation techniques, approaching trauma reminders) to relational partners reduces risk of psychological symptoms and bolsters the effectiveness of treatment. Further, research dedicated to understanding the timing of social support and the promotion of adaptive coping may be useful in uncovering empirically-informed answers to ‘when’ questions (e.g., “when are certain forms of social support most effective?;” “when is supplemental therapeutic support warranted / maximally effective?”).

Conclusion

The Integrated Biopsychosocial Model for Posttraumatic Stress Recovery assimilates multiple theoretical perspectives relating to the interplay of intrapersonal and interpersonal coping processes following a traumatic event. As such, this novel conceptual framework connects fairly disparate domains of empirical inquiry in an effort to holistically articulate the complexities of posttraumatic risk and resiliency. In its reflection of the state-of-the-field, the framework emphasizes the need to consider a multitude of transactional processes, particularly those relevant to understanding how interpersonal coping influences intrapersonal recovery. Using the framework as a guide, investigators can fill gaps in knowledge with continued experimental and clinical research that centers on identifying specific mechanisms through which interpersonal processes may contribute beneficially and detrimentally to stress recovery.

Notes

For the current definition, relational partners encompass anyone within an individual’s social circle (i.e., friends, family members, intimate partners, colleagues).

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Author: Washington, DC, USA. 2013.

Danielson CK, Cohen JR, Adams ZW, Youngstrom EA, Soltis K, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero KJ. Clinical decision-making following disasters: Efficient identification of PTSD risk in adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45(1):117–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0159-3.

Panagioti M, Gooding PA, Taylor PJ, Tarrier N. Perceived social support buffers the impact of PTSD symptoms on suicidal behavior: implications into suicide resilience research. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(1):104–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.06.004.

Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM. Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(8):745–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20558.

Fredette C, El-Baalbaki G, Palardy V, Rizkallah E, Guay S. Social support and cognitive–behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Traumatology. 2016;22(2):131–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000070.

Price M, Gros DF, Strachan M, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R. The role of social support in exposure therapy for Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom veterans: A preliminary investigation. Psychol Trauma. 2013;5(1):93–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026244.

Agaibi CE, Wilson JP. Trauma, PTSD, and resilience: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(3):195–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838005277438.

Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):748–66. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748.

Davis L, Siegel LJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a review and analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2000;3(3):135–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009564724720.

Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:52–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52.

Wright BK, Kelsall HL, Sim MR, Clarke DM, Creamer MC. Support mechanisms and vulnerabilities in relation to PTSD in veterans of the Gulf War, Iraq War, and Afghanistan deployments: a systematic review. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(3):310–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21809.

Feeney BC, Collins NL. A new look at social support: a theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2015;19(2):113–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544222.

Southwick SM, Sippel L, Krystal J, Charney D, Mayes L, Pietrzak R. Why are some individuals more resilient than others: the role of social support. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:77–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20282.

Christopher M. A broader view of trauma: a biopsychosocial-evolutionary view of the role of the traumatic stress response in the emergence of pathology and/or growth. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:75–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2003.12.003.

Haŝto J, Vojtova H, Hruby R, Tavel P. Biopsychosocial approach to psychological trauma and possible health consequences. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34(6):464–81 PMID: 24378444.

Cicchetti D. Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: a multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):145–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00297.x.

Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8(4):597–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400007318.

Saltzman LY, Hansel TC, Bordnick PS. Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12(S1):S55.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 1984.

Hyman SM, Gold SN, Cott MA. Forms of social support that moderate PTSD in childhood sexual abuse survivors. J Fam Violence. 2003;18:295–300. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025117311660.

Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: sequential roles of social causation and social selection. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(3):274–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20334.

McKeever VM, Huff ME. A diathesis-stress model of posttraumatic stress disorder: Ecological, biological, and residual stress pathways. Rev Gen Psychol. 2003;7(3):237–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.7.3.237.

Elwood LS, Hahn KS, Olatunji BO, Williams NL. Cognitive vulnerabilities to the development of PTSD: a review of four vulnerabilities and the proposal of an integrative vulnerability model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:87–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.002.

Bomyea J, Risbrough V, Lang AJ. A consideration of select pre-trauma factors as key vulnerabilities in PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(7):630–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.008.

Vogt D, King D, King L. Risk pathways for PTSD: Making sense of the literature. In: Friedman M, Keane T, Resick P, editors. Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice. New York: Guilford Press. 2007. p. 99–115.

Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: the role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(10):1129–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008.

Lopresti AL, Hood SD, Drummond PD. A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: diet, sleep and exercise. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:12–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.014.

Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: a bioecological model. Psychol Rev. 1994;101(4):568–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568.

Edes AN, Crews DE. Allostatic load and biological anthropology. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2017;162(63):44–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23146.

James GD, Brown DE. The biological stress response and lifestyle: catecholamines and blood pressure. Annu Rev Anthropol. 1997;26:313–35. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.313.

Hammen C. Stress generation in depression: reflections on origins, research, and future directions. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(9):1065–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20293.

Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):536–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jtg063.

Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Dev Perspect. 2013;7:43–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12013.

Williams DR. Stress and the mental health of populations of color: advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. J Health Soc Behav. 2018;59(4):466–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146518814251.

Abelson RP. Psychological status of the script concept. Am Psychol. 1981;36(7):715–29.

Bechara A, Damasio AR. The somatic marker hypothesis: A neural theory of economic decision. Games Econ Behav. 2005;52(2):336–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2004.06.010.

McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Res. 2000;886(1–2):172–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02950-4.

Danese A, Baldwin JR. Hidden wounds? Inflammatory links between childhood trauma and psychopathology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017;68:517–44. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044208.

Morris MC, Hellman N, Abelson JL, Rao U. Cortisol, heart rate, and blood pressure as early markers of PTSD risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;49:79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.001.

Passos IC, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Costa LG, Kunz M, Brietzke E, Quevedo J, Salum G, Magalhães PV, Kapczinski F, Kauer-Sant’Anna M. Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1002–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00309-0.

Teicher MH, Samson JA, Anderson CM, Ohashi K. The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(10):652–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.111.

Biggs A, Brough P, Drummond S. Lazarus and Folkman's psychological stress and coping theory. In Cooper CL, Quick JC, editors. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice, first edition. Wiley-Blackwell. 2017;351–364.

Dewe P, Cooper GL. Coping research and measurement in the context of work related stress. In: Hodgkinson GP, Ford JK, editors. Int Rev Ind Organ Psychol. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 2007;141–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753378.ch4.

Billings AG, Moos RH. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. J Behav Med. 1981;4(2):139–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00844267.

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56(2):267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267.

Luszczynska A, Benight CC, Cieslak R. Self-efficacy and health-related outcomes of collective trauma: A systematic review. Eur Psychol. 2009;14:51–62. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.51.

Park M, Chang ER, You S. Protective role of coping flexibility in PTSD and depressive symptoms following trauma. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;82:102–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.007.

Edwards JR, Baglioni AJ. Empirical versus theoretical approaches to the measurement of coping: A comparison using the ways of coping questionnaire and the cybernetic coping scale. In: Dewe P, Leiter M, Cox T, editors. Coping, health and Organizations. London: Taylor & Francis. 2000;29–50.

Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(4):319–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0.

Kaltas GA, Chrousos GP. The neuroendocrinology of stress. In: Cacioppo J, Tassinary L, Berntson G, editors. Handbook of psychophysiology. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2007;303–18.

Cobb AR, Josephs RA, Lancaster CL, Lee HJ, Telch MJ. Cortisol, testosterone, and prospective risk for war-zone stress-evoked depression. Mil Med. 2018;183(11–12):e535–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy065.

Josephs RA, Cobb AR, Lancaster CL, Lee HJ, Telch MJ. Dual-hormone stress reactivity predicts downstream war-zone stress-evoked PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;78:76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.013.

Morris MC, Compas BE, Garber J. Relations among posttraumatic stress disorder, comorbid major depression, and HPA function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(4):301–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.002.

Bendezú JJ, Sarah ED, Martha EW. What constitutes effective coping and efficient physiologic regulation following psychosocial stress depends on involuntary stress responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;73:42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.07.005.

Shansky RM, Lipps J. Stress-induced cognitive dysfunction: hormone-neurotransmitter interactions in the prefrontal cortex. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:123. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00123.

Shields GS, Sazma MA, Yonelinas AP. The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: A meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:651–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.038.

Rauch SL, Shin LM, Phelps EA. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: human neuroimaging research–past, present, and future. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):376–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.004.

Telch MJ, Rosenfield D, Lee HJ, Pai A. Emotional reactivity to a single inhalation of 35% carbon dioxide and its association with later symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety in soldiers deployed to Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1161–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.8.

Kim-Cohen J, Gold AL. Measured gene–environment interactions and mechanisms promoting resilient development. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(3):138–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01624.x.

Rasmussen LJH, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Danese A, Eugen-Olsen J, Fisher HL, Harrington H, Houts R, Matthews T, Sugden K, Williams B, Caspi A. Association of adverse experiences and exposure to violence in childhood and adolescence with inflammatory burden in young people. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:38–47. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3875.

Bremner JD, Elzinga B, Schmahl C, Vermetten E. Structural and functional plasticity of the human brain in posttraumatic stress disorder. Prog Brain Res. 2008;167:171–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67012-5.

Vaiva G, Thomas P, Ducrocq F, Fontaine M, Boss V, Devos P, Rascle C, Cottencin O, Brunet A, Laffargue P, Goudemand M. Low posttrauma GABA plasma levels as a predictive factor in the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(3):250–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.08.009.

Vaiva G, Ducrocq F, Jezequel K, Averland B, Lestavel P, Brunet A, Marmar CR. Immediate treatment with propranolol decreases posttraumatic stress disorder two months after trauma. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(9):947–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00412-8.

Anseel F, Beatty AS, Shen W, Lievens F, Sackett PR. How are we doing after 30 years? A meta-analytic review of the antecedents and outcomes of feedback-seeking behavior. J Manage. 2015;41:318–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313484521.

Cohen S, Gottlieb BH, Underwood LG. Social relationships and health. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: a guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press. 2000;3–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.003.0001.

Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. 1976;38:300–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003.

Cohen S, McKay G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In Handbook of psychology and health (Volume IV). Routledge. 2020;253–267.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Social support and victims of crime: matching event, support, and outcome. Am J Community Psychol. 1992;20(2):211–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00940837.

Norris FH, Kaniasty K. Received and perceived social support in times of stress: a test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(3):498–511. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.498.

Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D, Southwick S. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(5):35–40.

Southwick SM, Vythilingam M, Charney DS. The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: implications for prevention and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:255–91. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143948.

Dalgleish T, Joseph S, Thrasher S, Tranah T, Yule W. Crisis support following the Herald of Free-Enterprise disaster: a longitudinal perspective. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(4):833–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02104105.

Joseph S, Yule W, Williams R, Andrews B. Crisis support in the aftermath of disaster: a longitudinal perspective. Br J Clin Psychol. 1993;32(2):177–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1993.tb01042.x.

Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(6):885–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017376.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01.

Na PJ, Tsai J, Southwick S, Pietrzak R. Provision of social support and mental health in US military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. 2022. Preprint: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1374800/v1.

Kerns CE, Elkins RM, Carpenter AL, Chou T, Green JG, Comer JS. Caregiver distress, shared traumatic exposure, and child adjustment among area youth following the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:50–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.040.

Markowitz JC, Milrod B, Bleiberg K, Marshall RD. Interpersonal factors in understanding and treating posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(2):133–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000348366.34419.28.

Robinaugh DJ, Marques L, Traeger LN, Marks EH, Sung SC, Gayle Beck J, Pollack MH, Simon NM. Understanding the relationship of perceived social support to post-trauma cognitions and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(8):1072–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.07.004.

Byrne CA, Riggs DS. The cycle of trauma; relationship aggression in male Vietnam veterans with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Violence Vict. 1996;11(3):213–25 PMID: 9125790.

Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Fairbank JA, Schlenger WE, Kulka RA, Hough RL, Weiss DS. Problems in families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(6):916–26. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.916.

Nezu AM, Carnevale GJ. Interpersonal problem solving and coping reactions of Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987;96(2):155–7. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.96.2.155.

Plana I, Lavoie MA, Battaglia M, Achim AM. A meta-analysis and scoping review of social cognition performance in social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder and other anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(2):169–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.005.

Nietlisbach G, Maercker A. Social cognition and interpersonal impairments in trauma survivors with PTSD. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2009;18(4):382–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770902881489.

Wang Y, Chung MC, Wang N, Yu X, Kenardy J. Social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85: 101998.

Zalta AK, Tirone V, Orlowska D, Blais RK, Lofgreen A, Klassen B, Dent AL. Examining moderators of the relationship between social support and self-reported PTSD symptoms: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2021;147(1):33–54.

Valente TW, Gallaher P, Mouttapa M. Using social networks to understand and prevent substance use: a transdisciplinary perspective. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39(10–12):1685–712. https://doi.org/10.1081/ja-200033210.

Velting DM, Gould MS. Suicide contagion. In: Maris R, Silverman M, Sarsa S, editors. Rev of Suicidology. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. p. 96–137.

Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the trauma of rape: A cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1998.

Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(5):748–56. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748.

Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Dev. 2002;73(6):1830–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00509.

Schwartz-Mette RA, Rose AJ. Co-rumination mediates contagion of internalizing symptoms within youths’ friendships. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(5):1355–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027484.

Evraire LE, Dozois DJ. An integrative model of excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking in the development and maintenance of depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(8):1291–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.014.

Platt JM, Lowe SR, Galea S, Norris FH, Koenen KC. A longitudinal study of the bidirectional relationship between social support and posttraumatic stress following a natural disaster. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29(3):205–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22092.

Shallcross SL, Arbisi PA, Polusny MA, Kramer MD, Erbes CR. Social causation versus social erosion: comparisons of causal models for relations between support and PTSD symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29(2):167–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22086.

Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2(3):271–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

Ntontis E, Drury J, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ, Williams R, Saavedra P. Collective resilience in the disaster recovery period: Emergent social identity and observed social support are associated with collective efficacy, well-being, and the provision of social support. Br J Soc Psychol. 2021;60(3):1075–95.

Brymer M, Jacobs A, Layne C, Pynoos R, Ruzek J, Steinberg A, … Watson P. (National Child Traumatic Stress Network and National Center for PTSD), Psychological First Aid: Field Operations Guide, 2nd Edition. July 2006. Available on: www.nctsn.org and www.ptsd.va.gov.

Berkowitz S, Bryant R, Brymer M, Hambien J, Jacobs A, Layne C, … Watson P. The national center for PTSD & the national child traumatic stress network, skills for psychological recovery: field operations guide. 2010. Available on: www.nctsn.org and www.ptsd.va.gov.

Laursen B, Hoff E. Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill Palmer Quart. 2006;377–89. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0029.

Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL. Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge University Press. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499531.

Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Steer RA. A follow-up study of a multisite, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1474–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000240839.56114.bb.

Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(6):635–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.007.

Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(4):867–79. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867.

Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):393–402. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005.

Danielson CK, Adams Z, McCart MR, Chapman JE, Sheidow AJ, Walker J, Smalling A, de Arellano MA. Safety and efficacy of exposure-based risk reduction through family therapy for co-occurring substance use problems and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77(6):574–86. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4803.

Monson CM, Fredman SJ. Cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Therapist’s manual. New York, NY: Guilford. 2012.

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Predictors of treatment outcome in sexually abused children. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(7):983–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00153-8.

Monson CM, Taft CT, Fredman SJ. Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: from description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):707–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.002.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health grants T32 MH018869 (MPI: D. G. Kilpatrick & C. K. Danielson), T32MH015442 (PI: M. Laudenslager), T32 MH015755 (PI: D. Cicchetti), and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-1540502 awarded to K.J. Stone. Views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies acknowledged. NIMH and NSF had no role in drafting this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

The manuscript does not contain any studies with humans performed by the authors; therefore, informed consent was not obtained.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This article does not contain any studies with humans or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Calhoun, C.D., Stone, K.J., Cobb, A.R. et al. The Role of Social Support in Coping with Psychological Trauma: An Integrated Biopsychosocial Model for Posttraumatic Stress Recovery. Psychiatr Q 93, 949–970 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-022-10003-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-022-10003-w