Abstract

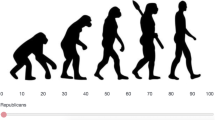

Two current members of the U.S. Supreme Court took their seats despite allegations of sexual harassment (Clarence Thomas) and sexual assault (Brett Kavanaugh) leveled against them during their confirmation hearings. In each instance, the Senate vote was close and split mainly along party lines: Republicans for and Democrats against. Polls showed that a similar division existed among party supporters in the electorate. There are, however, differences among rank-and-file partisans that help shape their views on the issues raised by these two controversial appointments to the nation’s highest court. Using data from a national survey of registered voters, we examine the factors associated with citizens’ attitudes about the role of women in politics, the extent to which sexism is a problem in society, the recent avalanche of sexual harassment charges made against elected officials and other political (as well as entertainment, business, and academic) figures, and the #MeToo movement. We are particularly interested in whether a strong sense of partisan identity adds significantly to our understanding of people’s attitudes on these matters. In addition, our experimental evidence allows us to determine whether shared partisanship overrides other factors when an elected official from one’s own party is accused of sexual misbehavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The dataset can be downloaded from: https://www.dropbox.com/s/u1xik7fdjz92c7q/CraigCossettePolBehavior_2018%20survey.dta?dl=0.

Code Availability

The code (Stata do file) can be downloaded here: https://www.dropbox.com/s/2qufmg4tfk6d9u0/PoliticalBehavior.do?dl=0.

Notes

The final vote was 52–48, split largely along party lines.

As of this writing, the VAWA has expired. Although the Democrat-controlled House passed a full re-authorization and revision of the bill in April 2019, the Senate has yet to act; see Willis (2019).

Following a series of misconduct cases that came to light in 2017 and 2018 (suggesting that the system was not working as intended), Congress passed new legislation that holds members personally liable for any financial settlements resulting from harassment and retaliation, and mandates a public reporting of any such settlements (Tully-McManus and Lesniewski 2018).

Reflecting on the Kavanaugh controversy, Jocelyn Frye, an African-American lawyer and senior fellow at the Center for American Progress in Washington, made the following observation: “27 years later, we have the same phenomenon rearing its head again. The people who have an interest in protecting the status quo... are attacking the integrity of Dr. Ford. It was hard to watch 27 years ago and it’s [agonizing] to watch now. To see many of the lessons that we should have learned in 1991 being ignored is infuriating” (D. Smith 2018).

Surveys conducted over the years give us little reason to believe that there is (or ever has been) a consensus among the American public as to what, exactly, constitutes sexual harassment. See, for example, Collins and Blodgett (1981), Kolbert (1991), Tinkler (2008), Kahn (2017); Daily Chart (2017). According to the aforementioned Ipsos/NPR poll from October 2018, 50% of all respondents (54% men, 46% women) agreed with the statement that “it can be hard sometimes to tell what is sexual harassment and what is not.” Moreover, behavior that is labeled by some as sexual harassment (e.g., solicitation for sex, “quid pro quo” harassment, inappropriate touching, etc.) is considered by others to be a form of sexual assault. In our study, some of these behaviors are classified as sexual harassment because we modeled our experimental treatments (described below) after news stories that reported alleged misconduct by prominent political figures. These stories typically framed the behaviors in question as harassment rather than assault, though we acknowledge that this line is blurry and any given act may be interpreted differently by different individuals.

While this statement is undoubtedly true, it fails to capture the nuances that are evident in public attitudes about sex crimes, offenders, and victims; for example, see Pickett et al. (2013), King and Roberts (2017), King (2019). However, in contrast to the lack of consensus reported in note 7, most Americans do have “a general conceptual understanding” of the difference between sexual assault and sexual harassment. When asked open-ended questions about how they would define these actions, respondents in the 2018 Ipsos/NPR survey tended to use more terms denoting “coercive action” regarding the former (e.g., ‘forcing,” “consent,” “attacked”), and more terms denoting “verbal or emotional forms of abuse” with respect to the latter (e.g., “feel,” “make,” “saying”). See https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/NPR-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault.

Although the success of Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, and others suggests that infidelity (especially when it involves a consensual act between adults, something that is rarely if ever the case for instances of workplace harassment) may not carry the stigma with voters that it once did, experience tells us that other kinds of “moral lapses” can exact a heavy political toll (Stanton 2015; Weiser 2017). In addition, there are offenses not involving either money or sex for which officeholders and candidates may be held accountable (Redlawsk and McCann 2005; Basinger 2013).

See Cossette and Craig (2020) and our supporting materials (the latter can be viewed at https://www.dropbox.com/s/rmakm2qmivojsn0/appendix.docx?dl=0) for additional details. Consistent with the results reported by Barnes and Cassese (2017), the gender gap on these items was greater among Republican identifiers than among Democrats. Even so, there is a subset of mostly white Republican women (and a smaller number of white female Democrats) who believe that women are less capable than men, who respond negatively to behavior that violates traditional gender stereotypes, who do not view gender inequality in society or politics as a function of discrimination or other structural obstacles facing women, and who therefore are less likely to be supportive of women who claim to have been victims of sexual harassment or assault. These attitudes are characteristic of what has been called “hostile sexism” and help to explain why the gender gap is not larger than it appears in our data. See Glick and Fiske (2001), Frasure-Yokley (2018), Cassese and Barnes (2019), Cassese and Holman (2019), Glick (2019), Luks and Schaffner (2019).

In this regard, little has changed since Clarence Thomas squared off against Anita Hill in 1991: https://www.aei.org/politics-and-public-opinion/the-anita-hill-controversy-what-the-polls-said/.

For more on partisan identity and affective polarization in contemporary American politics, see Green et al. (2002), Huddy et al. (2015), Iyengar and Westwood (2015), Ahler and Sood (2018), Iyengar and Krupenkin (2018), Levendusky (2018), Mason (2018), Sides et al. (2018), Strickler (2018), Egan (2019).

A qualitative approach focused on specific cases is probably better suited for observing the kind of back-and-forth that often occurs in real life. The drawback is that case study results, however insightful, cannot be generalized to the larger population of cases with which scholars are typically concerned.

The need for image repair might be present, for example, when a politician takes a policy position that is unpopular with constituents (McGraw 1990), faces negative attacks over the course of an election campaign (Craig et al. 2014), or is accused of engaging in some sort of illegal, unethical, or immoral behavior (Benoit 2017). This literature is discussed more fully in Cossette and Craig (2020).

Data were provided by Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com), a web interface and data collection service, from panels consisting of millions of pre-screened individuals recruited to participate in a variety of research studies. Respondents were drawn from a national panel and self-identified as registered voters. The sample was collected to meet demographic quotas reflecting the gender (53% female), race/ethnicity (72% identifying as non-Hispanic white, 12.7% African American, 9.7% Hispanic, 3.7% Asian, and 1.6% “other”), age (9.5% between 18 and 24, 15.6% between 25 and 34, 15.1% between 35 and 44, 17.8% between 45 and 54, 18.7% between 55 and 64, and 23.3% aged 65 and over), and education level (5.9% less than high school, 26.0% high-school graduates, 31.0% some college, 24.8% college graduates, and 12.4% with at least some post-graduate education) distributions of the population of registered voters as reported by the US Census. Our data include only respondents who completed the entire survey and who correctly answered two questions used as manipulation checks (see Cossette and Craig 2020). Although Qualtrics’s panel is quite diverse, we make no claim that it is representative of registered voters nationwide.

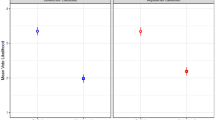

Index scores (alpha = 0.83 for Democrats, 0.83 for Republicans, 0.63 for Independents), which range from 3 to 15, were collapsed so that 13–15 = strong sense of identity (32.8% of Democrats, 27.5% of Republicans, and 25.2% of Independents), 10–12 = moderate sense of identity (29.9%, 33.7%, and 46.6%, respectively), and 3–9 = weak sense of identity (37.4%, 38.6%, 27.7%). One self-identified Republican and one Independent provided incomplete answers on the identity questions and were coded as missing.

Independent identity is less often studied and, as a result, less well-understood than its partisan counterparts. It is also perhaps less interesting theoretically, at least for our purposes (given that our experimental vignettes portray candidates with party affiliations), and prior research provides relatively little guidance as to how a strong group identity might be expected to shape the reactions of Independents to those vignettes. It does appear, however, that some self-identified Independents exhibit stronger in-group favoritism and out-group disaffection than others and that (the evidence is mixed here) this may lead to distinctive patterns of political behavior. Although strong-identity Independents might logically be expected to evaluate scandal-plagued candidates from both parties more negatively than weak-identity Independents, we include non-identifiers in our analysis primarily for purposes of comparison with Democrats and Republicans. For more on the nature of Independent identity, see Greene (1999, 2004), Klar (2014); Huddy et al. (2015); Klar and Krupnikov (2016).

Many respondents either took a “mixed/in-between” position with regard to #MeToo (17.9% Democrats, 23.1% Republicans) or did not “know enough about the movement” to offer an opinion (12.8% and 18.2%, respectively). A sizable number, including more Republicans than Democrats, also took a middle position on the other two questions noted here. See our supporting materials for details.

These biographies were crafted in such a way as to ensure that the two portrayals were essentially equivalent; see Fig. 1 and our supporting materials. To clarify: Each of our twelve vignettes pitted an incumbent (the target of allegations in all instances) against a challenger of the opposite party and sex. An effort was made to keep biographies free from any hint of controversy, e.g., both candidates were said to be married (with children), born and raised locally, college graduates with advanced degrees, military veterans, and active in civic organizations. Details for each man and each woman remained the same even as the party affiliation of the candidates varied across treatments.

The randomization process appears to have been successful, as no statistically significant pre-exposure differences were observed among members of the various groups with regard to demographics, partisanship, ideological self-identification, issue positions, or baseline candidate preferences. We can therefore be confident that any post-treatment differences were driven by the experimental stimuli.

The content of both allegations and responses was based on actual cases reported in the news, mostly during the period since the Weinstein scandal broke in October 2017. In writing the treatments for each combination of incumbent party and gender, the only words that varied were the candidate’s name, relevant pronouns, and a few small details to reflect differences in likely behavior based on candidate gender (e.g. the male incumbent was accused of touching a woman’s thighs, while the female was accused of touching a man’s buttocks). Otherwise, treatments for Democratic and Republican incumbents employ identical language; we provide the text for the male Republican here only as an example. Wordings for all twelve treatments can be found in our supporting materials.

The complete script for these responses is provided in our supporting materials. See Cossette and Craig (2020) for further details.

Ultimately, this is a question that will only be answered with the passage of time. For a discussion of other factors (including, among men, masculine identity, perceived threat to one’s masculinity, and narcissism) that may contribute to sexually inappropriate behavior, see Quinn (2002), Robinson (2005), Maass and Cadinu (2006), Berdahl (2007), McLaughlin et al. (2012), Zeigler-Hill et al. (2016), Berdahl et al. (2018), Walker (2018), Halper and Rios (2019).

Although this might seem counterintuitive, it is based on the fact that very few out-party identifiers supported the incumbent (5.3% for a male incumbent, 13.2% for a female) even before reading about the harassment allegations. As noted by Vonnahme (2014; also see von Sikorski et al. 2019) and confirmed by her experimental data, “opponents of a candidate may have little room to downgrade their evaluation of the candidate, whereas affect has substantial room to plummet among supporters after scandal involvement” (p. 1311).

The complete dataset can be found at https://www.dropbox.com/s/u1xik7fdjz92c7q/CraigCossettePolBehavior_2018%20survey.dta?dl=0.

Although the difference here (p < 0.01) suggests that Independents may be more likely to punish women than men for sexual misconduct, the post-allegation decline in favorability does not vary significantly by candidate gender among this group.

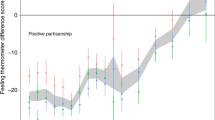

We look at change in this instance using OLS because, unlike vote preference, the favorability variable is not dichotomous. When this model is replicated using favorability at T2 as our dependent variable (and including favorability at T1 as a predictor), results are very similar to those portrayed in Fig. 3. The same is true when we run the favorability model using ordered logit, with favorability at T2 as dependent (and including favorability at T1 as a predictor).

See Fig. A1 in our supporting materials.

Results are similar for incumbent favorability, with one exception: while the probability of Democratic co-partisans voting for the incumbent at T2 increased at higher levels of partisan identity, stronger-identity co-partisans actually reduced their favorability score to a greater extent following the allegations than did their weaker-identity counterparts (see Fig. A2 in our supporting materials for details).

See Benoit (2015)

T-test tables can be found in our supporting materials.

While some might worry that our results will encourage sexual predators to employ such an account strategy in a cynical (and dishonest) effort to salvage their political career, we believe that there are times when a denial is simply not credible, at least in the long run. Further, the lack of clear evidence makes it difficult in many “she said/he said” disputes to determine what actually happened—but this seems more likely to be the case when sexual assault is alleged than in cases involving workplace harassment, where the presence of witnesses and multiple accusers telling reinforcing stories may leave less reason to doubt that the behavior in question occurred. For a consideration of the effectiveness of denial relative to other account strategies, see Benoit (2015).

See Cossette and Craig (2020) for additional details, as well as Fig. A3 and Tables A3 and A4b in our supporting materials. In most cases, denial also was the most effective response for (partially) reversing the loss of favorability that occurred following a reading of the allegations.

As with the post-allegation findings, we observe differences between the results for vote and favorability for the Democratic incumbent. Whereas Democratic co-partisans and Independents with stronger partisan identities were more likely to vote for the incumbent after reading the response, the opposite was true for favorability; that is, strong-identity Democrats and Independents reduced the rating of the Democratic incumbent more than weak identifiers at T3. For the Republican incumbent, similar results were observed for vote choice and favorability (see our supporting materials for details).

Respondents were asked at T3 whether they agreed or disagreed with “those who are calling for [name] to resign [his/her] seat in Congress?” Our analysis indicated that identity helped to shape the attitudes of Republican voters (but not of Democrats) on this question; specifically, those with a strong attachment were more likely than weak-identity Republicans to support resignation—but only when the incumbent in question was a Democrat. See Cossette and Craig (2020) for further details.

References

Agiesta, J., & Sparks, G. (2018, October 11). CNN poll: Two-thirds call sexual harassment a serious problem in the US today. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/11/politics/sexual-harassment-poll/index.html.

Ahler, D. J., & Sood, G. (2018). The parties in our heads: Misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. Journal of Politics, 80(3), 964–981.

Baekgaard, M., Christenser, J., Mondrup Dahlmann, C., Mathiesen, A., & Petersen, B. G. (2019). The role of evidence in politics: Motivated reasoning and persuasion among politicians. British Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 1117–1140.

Barnes, T. D., & Beaulieu, E. (2014). Gender stereotypes and corruption: How candidates affect perceptions of election fraud. Politics and Gender, 10(3), 365–391.

Barnes, T. D., & Beaulieu, E. (2019). Women politicians, institutions, and perceptions of corruption. Comparative Political Studies, 52(1), 134–167.

Barnes, T. D., Beaulieu, E., & Saxton, G. W. (2018). Sex and corruption: How sexism shapes voters’ responses to scandal. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 8(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1441725.

Barnes, T. D., & Cassese, E. C. (2017). American party women: A look at the gender gap within parties. Political Research Quarterly, 70(1), 127–141.

Basinger, S. J. (2013). Scandals and congressional elections in the post-Watergate era. Political Research Quarterly, 66(2), 385–398.

Benoit, W. L. (2015). Accounts, excuses, and apologies: Image repair theory and research (2nd ed.). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Benoit, W. L. (2017). Image repair on the Donald Trump “Access Hollywood” video: “Grab them by the p*ssy”. Communication Studies, 68(3), 243–259.

Benoit, W. L., & Brinson, S. L. (1994). AT&T: “Apologies are not enough.” Communication Quarterly, 42(1), 75–88.

Berdahl, J. L. (2007). Harassment based on sex: Protecting social status in the context of gender hierarchy. The Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 641–658.

Berdahl, J. L., Cooper, M., Glick, P., Livingston, R. W., & Williams, J. C. (2018). Work as a masculinity contest. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 422–448.

Berelson, B. R., Lazarsfeld, P. F., & McPhee, W. N. (1954). Voting: A study of opinion formation in a presidential campaign. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Berinsky, A. J., Hutchings, V. L., Mendelberg, T., Shaker, L., & Valentino, N. A. (2011). Sex and race: Are black candidates more likely to be disadvantaged by sex scandals? Political Behavior, 33(2), 179–202.

Bisgaard, M. (2019). How getting the facts right can fuel partisan-motivated reasoning. American Journal of Political Science, 63(4), 824–839.

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., & Lomax Cook, F. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36(2), 235–262.

Bongiorno, R., Langbroek, C., Bain, P. G., Ting, M., & Ryan, M. K. (2020). Why women are blamed for being sexually harassed: The effects of empathy for female victims and male perpetrators. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(1), 11–27.

Bouchard, M., & Taylor, M. S. (2018, September 27). Flashback: The Anita Hill hearings compared to today. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/27/us/politics/anita-hill-kavanaugh-hearings.html.

Brown, L. M. (2006). Revisiting the character of Congress: Scandals in the U.S. House of Representatives, 1966–2002. Journal of Political Marketing, 5(1–2), 149–172.

Burgoon, J. K., & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Communication Monographs, 55(1), 58–79.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. New York, NY: Wiley.

Carlson, J., Ganiel, G., & Hyde, M. S. (2000). Scandal and political candidate image. Southeastern Political Review, 28(4), 747–757.

Cassese, E. C., & Barnes, T. D. (2019). Reconciling sexism and women’s support for Republican candidates: A look at gender, class, and whiteness in the 2012 and 2016 presidential races. Political Behavior, 41(3), 677–700.

Cassese, E. C., & Holman, M. R. (2019). Playing the woman card: Ambivalent sexism in the 2016 U.S. presidential race. Political Psychology, 40(1), 55–74.

Collins, E. G. C., & Blodgett, T. B. (1981). Sexual harassment … some see it … some won’t. Harvard Business Review, 59(2), 76–94.

Cossette, P. S., & Craig, S. C. (2020). Politicians behaving badly: Men, women, and the politics of sexual harassment. New York, NY: Routledge.

Courtemanche, M., & Green, J. C. (2020). A fall from grace: Women, scandals, and perceptions of politicians. Journal of Women, Politics and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2020.1723055.

Craig, S. C., Rippere, P. S., & Grayson, M. S. (2014). Attack and response in political campaigns: An experimental study in two parts. Political Communication, 31(4), 647–674.

Daily Chart. (2017, November 17). Over-friendly or sexual harassment? It depends partly on whom you ask. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/11/17/over-friendly-or-sexual-harassment-it-depends-partly-on-whom-you-ask.

DeBonis, M. (2018, September 19). “I told her that I believed her”: Calif. lawmaker describes meeting with Kavanaugh accuser. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2018/09/19/i-told-her-that-i-believed-her-calif-lawmaker-describes-meeting-with-kavanaugh-accuser/.

Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., & Miller, M. G. (2011). Are financial or moral scandals worse? It depends. PS: Political Science and Politics, 44(4), 749–757.

Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., & Miller, M. G. (2014). Does time heal all wounds? Sex scandals, tax evasion, and the passage of time. PS: Political Science and Politics, 47(2), 357–366.

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57–79.

Edelson, J., Alduncin, A., Krewson, C., Sieja, J. A., & Uscinski, J. E. (2017). The effect of conspiratorial thinking and motivated reasoning on belief in election fraud. Political Research Quarterly, 70(4), 933–946.

Egan, P. J. (2019). Identity as dependent variable: How Americans shift their identities to align with their politics. American Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12496.

Eggers, A. C., Vivyan, N., & Wagner, M. (2018). Corruption, accountability, and gender: Do female politicians face higher standards in public life? Journal of Politics., 80(1), 321–326.

Frasure-Yokley, L. (2018). Choosing the velvet glove: Women voters, ambivalent sexism, and vote choice in 2016. Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 3(SI1), 3–25.

Funk, C. L. (1996). The impact of scandal on candidate evaluations: An experimental test of the role of candidate traits. Political Behavior, 18(1), 1–24.

Gibson, C. & Guskin, E. (2017, October 17). A majority of Americans now say that sexual harassment is a “serious problem.” Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/a-majority-of-americans-now-say-that-sexual-harassment-is-a-serious-problem/2017/10/16/707e6b74-b290-11e7-9e58-e6288544af98_story.html.

Glick, P. (2019). Gender, sexism, and the election: Did sexism help Trump more than it hurt Clinton? Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(3), 713–723.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118.

Grady, C., & Framke, C. (2017, December 13). All the women who have accused Harvey Weinstein of sexual harassment and assault, so far. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/10/11/16460164/harvey-weinstein-sexual-harassment-assault-accusations.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (1999). Understanding party identification: A social identity approach. Political Psychology, 20(2), 393–403.

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153.

Halper, L. R., & Rios, K. (2019). Feeling powerful but incompetent: Fear of negative evaluation predicts men’s sexual harassment of subordinates. Sex Roles, 80(5–6), 247–261.

Hamel, B. T., & Miller, M. G. (2019). How voters punish and donors protect legislators embroiled in scandal. Political Research Quarterly, 72(1), 117–131.

Hattery, A. J., & Smith, E. (2019). Gender, power, and violence: Responding to sexual and intimate partner violence in society today. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Herbst, D. (2018, April 19). Trump sexual assault accusers find unlikely heroine in Stormy Daniels: “She’s got a lot of guts.” People. Retrieved from https://people.com/politics/trump-sexual-assault-accusers-praise-stormy-daniels/.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17.

Iyengar, S., & Krupenkin, M. (2018). The strengthening of partisan affect. Political Psychology, 39(suppl. 1), 201–218.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Johnson, T. (2018). Deny and attack or concede and correct? Image repair and the politically scandalized. Journal of Political Marketing, 17(3), 213–234.

Junn, J., Masuoka, N., & Grose, C. (2018). Sexual harassment and candidate evaluation. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association, Boston, MA.

Kahn, Chris. (2017, December 27). Poll: Hugs and dirty jokes – Americans differ on acceptable behavior. Reuters.com. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-metoo-poll/poll-hugs-and-dirty-jokes-americans-differ-on-acceptable-behavior-idUSKBN1EL147.

Kantor, J., & Twohey, M. (2017, October 5). Harvey Weinstein paid off sexual harassment accusers for decades. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/us/harvey-weinstein-harassment-allegations.html.

King, L. L. (2019). Perceptions about sexual offenses: Misconceptions, punitiveness, and public sentiment. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 30(2), 254–273.

King, L. L., & Roberts, J. J. (2017). The complexity of public attitudes toward sex crimes. Victims and Offenders, 12(1), 71–89.

Klar, S. (2014). Identity and engagement among political Independents in America. Political Psychology, 35(4), 577–591.

Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. (2016). Independent politics: How American disdain for parties leads to political inaction. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kolbert, E. (1991, October 11). The Thomas nomination: Sexual harassment at work is pervasive, survey suggests. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/11/us/the-thomas-nomination-a-case-study-of-sexual-harassment.html.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

Levendusky, M. S. (2018). Americans, not partisans: Can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? Journal of Politics, 80(1), 59–70.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Luks, S., & Schaffner, B. (2019, July 11). New polling shows how much sexism is hurting the Democratic women running for president. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/07/11/women-candidates-must-overcome-sexist-attitudes-even-democratic-primary/.

Maass, A., & Cadinu, M. R. (2006). Protecting a threatened identity through sexual harassment: A social identity interpretation. In R. Brown & D. Capozza (Eds.), Social identities: Motivational, emotional and cultural influences (pp. 109–132). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Mason, L. (2016). A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80, 351–377.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mason, L., & Wronski, J. (2018). One tribe to bind them all: How our social group attachments strengthen partisanship. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 257–277.

Maule, L. S., & Goidel, R. K. (2003). Adultery, drugs, and sex: An experimental investigation of individual reactions to unethical behavior by public officials. Social Science Journal, 40(1), 65–78.

McGraw, K. M. (1990). Avoiding blame: An experimental investigation of political excuses and justification. British Journal of Political Science, 20(1), 119–129.

McLaughlin, H., Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2012). Sexual harassment, workplace authority, and the paradox of power. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 625–647.

Miller, P. R., & Johnston Conover, P. (2015). Red and blue states of mind: Partisan hostility and voting in the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 68(2), 225–239.

Pereira, M. M., & Waterbury, N. W. (2019). Do voters discount political scandals over time? Political Research Quarterly, 72(3), 584–595.

Peterson, D. A. M., & Vonnahme, B. M. (2014). Aww, shucky ducky: Voter response to accusations of Herman Cain’s “inappropriate behavior.” PS: Political Science and Politics, 47(2), 372–378.

Pew Research Center. (2018, September 20). Women and leadership 2018. Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/09/20/women-and-leadership-2018/.

Pickett, J. T., Mancini, C., & Mears, D. P. (2013). Vulnerable victims, monstrous offenders, and unmanageable risk: Explaining public opinion on the social control of sex crime. Sociology, 51(3), 729–759.

Popovich, P. M., & Warren, M. A. (2010). The role of power in sexual harassment as a counterproductive behavior in organizations. Human Resource Management Review, 20(1), 45–53.

Praino, R., Stockemer, D., & Moscardelli, V. M. (2013). The lingering effect of scandals in congressional elections: Incumbents, challengers, and voters. Social Science Quarterly, 94(4), 1045–1061.

PRRI (Public Religion Research Institute). (2018). Partisanship trumps gender: Sexual harassment, woman candidates, access to contraception, and key issues in 2018 midterms. Retrieved from https://www.prri.org/research/abortion-reproductive-health-midterms-trump-kavanaugh/.

Puente, M. (2017, December 18). Women are rarely accused of sexual harassment, and there’s a reason why. USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.king5.com/article/news/nation-now/women-are-rarely-accused-of-sexual-harassment-and-theres-a-reason-why/465-0c6438fe-a68c-4acc-bfed-49588c95c00c.

Quinn, B. A. (2002). Sexual harassment and masculinity: The power and meaning of “girl watching.” Gender and Society, 16(3), 386–402.

Redlawsk, D. P., Civettini, A. J. W., & Emmerson, K. M. (2010). The affective tipping point: Do motivated reasoners ever “get it”? Political Psychology, 31(4), 563–593.

Redlawsk, D. P., & McCann, J. A. (2005). Popular interpretations of “corruption” and their partisan consequences. Political Behavior, 27(3), 261–283.

Rikleen, L. S. (2019). The shield of silence: How power perpetuates a culture of harassment and bullying in the workplace. Chicago, IL: American Bar Association.

Robinson, K. H. (2005). Reinforcing hegemonic masculinities through sexual harassment: Issues of identity, power and popularity in secondary schools. Gender and Education, 17(1), 19–37.

Rosenwald, M. S. (2018, September 18). No women served on the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991. The ugly Anita Hill hearings changed that. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2018/09/18/no-women-served-senate-judiciary-committee-ugly-anita-hill-hearings-changed-that/.

Rundquist, B. S., Strom, G. S., & Peters, J. G. (1977). Corrupt politicians and their electoral support: Some experimental observations. American Political Science Review, 77(3), 954–963.

Saguy, A. C. (2003). What is sexual harassment? From Capitol Hill to the Sorbonne. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schaffner, B. F., & Roche, C. (2017). Misinformation and motivated reasoning: Responses to economic news in a politicized environment. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81(1), 86–110.

Sides, J., Tesler, M., & Vavreck, L. (2018). Identity crisis: The 2016 presidential campaign and the battle for the meaning of America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sigal, J., Hsu, L., Foodim, S., & Betman, J. (1988). Factors affecting perceptions of political candidates accused of sexual and financial misconduct. Political Psychology, 9(2), 273–280.

Smith, D. (2018, September 22). Anita Hill and the Senate “sham trial” that echoes down to Kavanaugh. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/law/2018/sep/22/brett-kavanaugh-christine-blasey-ford-anita-hill-clarence-thomas-senate-judiciary-committee.

Smith, E. S., & Powers, A. S. (2005). If Bill Clinton were a woman: The effectiveness of male and female politicians’ account strategies following alleged transgressions. Political Psychology, 26(6), 115–134.

Smith, T. (2018, October 31). On #MeToo, Americans more divided by party than gender. NPR.org. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/10/31/662178315/on-metoo-americans-more-divided-by-party-than-gender.

Sparks, G. (2018, September 4). Would voters prefer men or women on the ballot? This poll asked. CNN.com. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2018/09/04/politics/voters-support-women-over-men/index.html.

Stanton, Z. (2015, November 20). The page who took down the GOP: Why I leaked the scandalous Mark Foley messages – and what I regret about it. Politico. Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/11/the-page-who-took-down-the-gop-mark-foley-dennis-hastert-213378.

Stemple, L., & Meyer, I. H. (2017, October 10). Sexual victimization by women is more common than previously known. Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/sexual-victimization-by-women-is-more-common-than-previously-known/.

Stolberg, S. G. (2011, June 11). When it comes to scandal, girls won’t be boys. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/12/weekinreview/12women.html?_r=0.

Strickler, R. (2018). Deliberate with the enemy? Polarization, social identity, and attitudes toward disagreement. Political Research Quarterly, 71(1), 3–18.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769.

Terkel, A. (2017, October 11). 26 years ago, American started talking about sexual harassment thanks to Anita Hill. Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/anita-hill-26-years-sexual-harassment_n_59deaf0fe4b0fdad73b1e9bf.

Theodoridis, A. (2019, July 25). Surprise! Most Republicans and Democrats identify more with their own party than against the other party. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/07/25/surprise-most-republicans-democrats-identify-more-with-their-own-party-than-against-other-party/.

Tinkler, J. E. (2008). “People are too quick to take offense”: The effects of legal information and beliefs on definitions of sexual harassment. Law and Social Inquiry, 33(2), 417–446.

Tully-McManus, K., & Lesniewski, N. (2018, December 21). Donald Trump signs overhaul of anti-harassment law for members of Congress, staff. Roll Call. Retrieved from https://www.rollcall.com/2018/12/21/donald-trump-signs-overhaul-of-anti-harassment-law-for-members-of-congress-staff/.

Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2004). Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review, 69(1), 64–92.

von Sikorski, C. (2018). The aftermath of political scandals: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Communication, 12, 3109–3133.

von Sikorski, C., Heiss, R., & Matthes, J. (2019). How political scandals affect the electorate: Tracing the eroding and spillover effects of scandals with a panel study. Political Psychology, 41(3), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12638.

Vonnahme, B. M. (2014). Surviving scandal: An exploration of the immediate and lasting effects of scandal on candidate evaluation. Social Science Quarterly, 95(5), 1308–1321.

Walker, S. (2018). Parties to the crime: Locus of control as a catalyst to sexually harassing behaviors. Academy of Business Research Journals, 1, 41–52.

Watson, D., & Moreland, A. (2014). Perceptions of corruption and the dynamics of women’s representation. Politics and Gender, 10(3), 392–412.

Weiser, B. (2017, September 25). Anthony Weiner gets 21 months in prison for sexting with teenager. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/25/nyregion/anthony-weiner-sentencing-prison-sexting-teenager.html.

Welch, S., & Hibbing, J. R. (1997). The effects of charges of corruption on voting behavior in congressional elections, 1982–1990. Journal of Politics, 59(1), 226–239.

Whiting, J. (2019, January 16). How denial and victim blaming keep sexual assault hidden. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/love-lies-and-conflict/201901/how-denial-and-victim-blaming-keep-sexual-assault-hidden.

Willis, J. (2019, December 13). Why can’t the Senate pass the Violence Against Women Act? GQ.com. Retrieved from https://www.gq.com/story/senate-violence-against-women-act.

Wolf, R., & Hayes, C. (2018, October 6). Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh: The plot twists and moments that got us here. USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/10/06/brett-kavanaugh-moments-supreme-court-confirmation/1539791002/.

Zeigler-Hill, V., Besser, A., Morag, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2016). The dark triad and sexual harassment proclivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 47–54.

Funding

The survey in this study was funded by the University of Florida Graduate Program in Political Campaigning and the Washington College Faculty Enhancement Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Craig, S.C., Cossette, P.S. Eye of the Beholder: Partisanship, Identity, and the Politics of Sexual Harassment. Polit Behav 44, 749–777 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09631-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09631-4