Abstract

Studies of gender-ideology stereotypes suggest that voters evaluate male and female candidates in different ways, yet data limitations have hindered an analysis of candidate ideology, sex, and actual election outcomes. This article draws on a new dataset of male and female primary and general election candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives from 1980 to 2012. I find little evidence that the relationship between ideology and victory patterns differs for male and female candidates. Neither Republican nor Democratic women experience distinct electoral fates than ideologically similar men. Candidate sex and ideology do interact in other ways, however; Democratic women are more liberal than their male counterparts, and they are advantaged in primaries over Republican women as well as Democratic men. The findings have important implications for contemporary patterns of women’s representation, and they extend our understanding of gender bias and neutrality in American elections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The magnitude of the effect of candidate sex on perceptions of candidate ideology is much smaller than that of factors like respondent ideology, feeling thermometer ratings, and perceptions of party ideology (Koch 2002, p. 421). Moreover, the size of the effect of actual candidate ideology on voter perceptions of her ideology is between two and four times that of candidate sex (Koch 2002, p. 421).

The DIME dataset includes candidates who filed with the FEC. Candidates who do not exceed the $5000 threshold of campaign fundraising are not required to file. Those who are excluded are thus more likely to be long-shot candidates, but it is not clear that they are more likely to be ideologues or moderates. Even so, these excluded candidates comprise only 6% of primary winners and 0.02% of general election winners, so they are highly unlikely to have an influence on policy outcomes or women’s representation. Furthermore, these data provide the best publicly available measures of the ideological positions of congressional winners and losers over time.

Bonica suggests that contribution records may even offer a more complete measure of ideology than does legislative voting. Contributors can consider factors beyond candidates’ voting behavior, such as policy goals, endorsements, or cultural values. Yet Bonica’s goal is not to replicate DW-NOMINATE scores, and he notes that the two measures should be viewed as complementary.

These averages include races in which candidates do and do not face opposition.

Ideology could also be measured as liberalism, but I opted to use this measure in light of the above research on whether conservatism has a stronger effect on election outcomes for female candidates.

Candidate sex was unable to be identified in 13 cases.

Pettigrew et al.’s (2014) data and the data presented here are virtually identical. There are very minor discrepancies due to the omission of a few states and/or districts in a handful of years, but the fact that they were collected independently provides further validation to both datasets.

I calculated the total number of primary candidates by party, congressional district, and year. The number of candidates was calculated by congressional district and year in states where the top two vote getters advance to the general, regardless of party (i.e., CA, LA, and WA in various cycles).

I also ran the models with controls for partisan eras (1980–1992; 1994–2004; 2006–2012), and the results are virtually identical to those presented below (see Table 3). In addition, I account for whether it was a presidential election year and whether the candidate was running in the South, and the results are the same (see Table 4). Standard errors are clustered by race in the primary models.

Like Lawless and Pearson (2008), I exclude primary and general election candidates who are unopposed. Of the 17,639 primary candidates with CFscores, 7606 (43%) were unopposed; of the 12,632 general election candidates with CFscores, 916 were unopposed (7%). This figure is higher than the percentage of unopposed candidates in the full sample of 24,125 primary candidates (35%), because those with CFscores were more likely to run unopposed than those without CFscores (43% and 12%, respectively). Since the focus is on the interaction between candidate ideology and sex, the candidates with ideology scores are of primary interest here.

I also ran logistic regression models, and these results are presented in Table 5. I also present the most basic specification of the models with ideology, sex, the interaction term, and incumbent (Table 6). Lastly, I ran the models with primary and general election vote share as the dependent variable (Table 7), but I opted to focus on victory rates because they are of ultimate relevance for patterns of women’s representation. Across specifications, the results remain largely the same, and the interaction term does not reach conventional levels of significance. The sole exception is the general election model for Democrats in Table 7, but again, the size of the coefficient is small, and the overwhelming pattern indicates statistical and substantive insignificance across models.

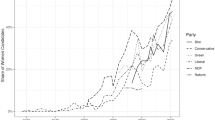

It is possible that the pooled models mask variation over time and that sex and ideology were associated with victory rates in the 1980s and early 1990s. To examine this question, I ran separate models for each election year (see Lawless and Pearson 2008 and Frederick 2009 for similar empirical approaches). The results are presented in Fig. 6. In general, the relationship between ideology and election outcomes does not differ for men and women across this 30-year period.

All other variables are set at their mean or mode so these values are for non-incumbents.

Candidate quality has long been a key factor in congressional elections as well, but data limitations prevent its inclusion here. Pettigrew et al.’s (2014) dataset includes the previous political experience of primary candidates from 2000 to 2010, and this variable is correlated with campaign receipts at 0.60 and with incumbent at 0.82 so I am confident the models are capturing a key dimension of quality. Yet I also ran the models with this measure of candidate quality among non-incumbents from 2000 to 2010, and the interaction term is insignificant (see Table 8).

Male and female candidates were statistically indistinguishable in all five categories. The ideology category controls are not shown in Table 2, but the coefficients are not significant.

These values are calculated from the models in Table 1. Additional models that exclude the interaction term are provided in Tables 9 and 10. In the primary models, candidate sex is insignificant for Republicans but positive and significant for Democrats, with and without the inclusion of ideology. In the general election models, candidate sex is insignificant for Republicans but negative and significant for Democrats, with and without the inclusion of ideology.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., Alexander, B., & Gunning, M. (2006). Incumbency, redistricting, and the decline of competition in U.S. House elections. Journal of Politics,68(1), 75–88.

Ansolabehere, S., Snyder, J. M., Jr., & Stewart, C., III. (2001). Candidate positioning in U.S. House elections. American Journal of Political Science,45(1), 136–159.

Bauer, N. M. (2015). Who stereotypes female candidates? Identifying individual differences in feminine stereotype reliance. Politics, Groups, and Identities,3(1), 94–110.

Bonica, A. (2014). Mapping the ideological marketplace. American Journal of Political Science,58(2), 367–387.

Bonica, A., McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2013). Why hasn’t democracy slowed rising inequality. Journal of Economic Perspectives,27(3), 103–124.

Brady, D. W., Han, H., & Pope, J. C. (2007). Primary elections and candidate ideology: out of step with the primary electorate? Legislative Studies Quarterly,32(1), 79–105.

Brooks, D. J. (2013). He runs, she runs: Why gender stereotypes do not harm women candidates. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Burden, B. (2004). Candidate positioning in U.S. congressional elections. British Journal of Political Science,34(2), 211–227.

Burrell, B. C. (1994). A woman’s place is in the house: Campaigning for congress in the feminist era. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Burrell, B. C. (2014). Gender in campaigns for the U.S. House of representatives. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Canes-Wrone, B., Brady, D. W., & Cogan, J. F. (2002). Out of step, out of office: Electoral accountability and house members’ voting. American Political Science Review,106(1), 103–122.

Carroll, S. J. (1994). Women as candidates in American politics (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Cassese, E. C., & Holman, M. R. (2017). Party and gender stereotypes in campaign attacks. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9423-7.

Cook, E. A. (1998). Voter reaction to women candidates. In S. Thomas & C. Wilcox (Eds.), Women and elective office. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cooperman, R., & Oppenheimer, B. I. (2001). The gender gap in the house of representatives. In L. C. Dodd & B. I. Oppenheimer (Eds.), Congress reconsidered (7th ed.). Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Crowder-Meyer, M., & Lauderdale, B. E. (2014). A partisan gap in the supply of female potential candidates in the United States. Research and Politics,1(1), 1–7.

Darcy, R., Welch, S., & Clark, J. (1994). Women, elections, and representation (2nd ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Ditonto, T., Hamilton, A. J., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2014). Gender stereotypes, information search, and voting behavior in political campaigns. Political Behavior,36(2), 335–358.

Dolan, K. (2014). When does gender matter? Women candidates and gender stereotypes in American elections. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dolan, K. A. (2004). Voting for women: How the public evaluates women candidates. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Duerst-Lahti, G. (1998). The Bottleneck, women as candidates. In S. Thomas & C. Wilcox (Eds.), Women and elective office: Past, present, and future. New York: Oxford University Press.

Elder, L. (2008). Whither republican women: The growing partisan gap among women in congress. The Forum,6(1), 1–21.

Erikson, R. S., & Wright, G. C., Jr. (2000). Representation of constituency ideology in congress. In D. W. Brady, J. F. Cogan, & M. P. Fiorina (Eds.), Continuity and change in house elections. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Frederick, B. (2009). Are female house members still more liberal in a polarized era? The conditional nature of the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation. Congress & the Presidency,36(2), 181–202.

Freeman, J. (1986). The political culture of the democratic and republican parties. Political Science Quarterly,101(3), 327–356.

Fulton, S. A. (2012). Running backwards and in high heels: The gendered quality gap and electoral success. Political Research Quarterly,65(2), 303–314.

Gaddie, R. K., & Bullock, C. S., III. (2000). Elections to open seats in the U.S. House: Where the action is. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Grossman, M., & Hopkins, D. A. (2015). Ideological Republicans and group interest Democrats: The asymmetry of American party politics. Perspectives on Politics,13(1), 119–139.

Hall, A. B., & Snyder, J. M. Jr. (2015). Candidate ideology and electoral success. Working Paper, Harvard University.

Hayes, D. (2011). When gender and party collide: Stereotyping in candidate trait attribution. Politics & Gender,7(2), 133–165.

Hayes, D., & Lawless, J. L. (2015). A non-gendered lens? Media, voters, and female candidates in contemporary congressional elections. Perspectives on Politics,13(1), 95–118.

Hayes, D., Lawless, J. L., & Baitinger, G. (2014). Who cares what they wear? Media, gender, and the influence of candidate appearance. Social Science Quarterly,95(5), 1194–1212.

Hetherington, M. J. (2001). Resurgent mass partisanship: The role of elite polarization. American Political Science Review,95(3), 619–631.

Hirano, S., Snyder, J. M., Jr., Ansolabehere, S., & Hansen, J. M. (2010). Primary elections and partisan polarization in the U.S. congress. Quarterly Journal of Political Science,5(2), 169–191.

Holman, M. R., Merolla, J. L., & Zechmeister, E. J. (2016). Terrorist threat, male stereotypes, and candidate evaluations. Political Research Quarterly,69(1), 134–147.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993). The consequences of gender stereotypes for women candidates at different levels and types of office. Political Research Quarterly,46(3), 503–525.

Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). (2017). Women in National Parliaments, 2017. http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm. Accessed June 2017.

Jacobson, G. (2013). The politics of congressional elections (8th ed.). New York: Pearson.

Jacobson, G. C. (2015). It’s nothing personal: The decline of the incumbency advantage in US house elections. Journal of Politics,77(3), 861–873.

King, D., & Matland, R. (2003). Sex and the grand old party: An experimental Investigation of the effect of candidate sex on support for a republican candidate. American Politics Research,31(6), 595–612.

Koch, J. (2000). Do citizens apply gender stereotypes to infer candidates’ ideological orientations? American Journal of Political Science,62(2), 414–429.

Koch, J. (2002). Gender stereotypes and citizens’ impressions of house candidates’ ideological orientations. American Journal of Political Science,46(2), 453–462.

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Women, war, and winning elections: Gender stereotyping in the post-september 11th era. Political Research Quarterly,57(3), 479–490.

Lawless, J. L., & Pearson, K. (2008). The primary reason for women’s underrepresentation? Reevaluating the conventional wisdom. Journal of Politics,70(1), 67–82.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became Democrats and conservatives became Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McDermott, M. (1997). Voting cues in low-information elections: Candidate gender as a social information variable in contemporary United States elections. American Journal of Political Science,41(1), 270–283.

McDermott, M. (1998). Race and gender cues in low information elections. Political Research Quarterly,51(4), 895–918.

Milyo, J., & Schosberg, S. (2000). Gender bias and selection bias in house elections. Public Choice,105(1/2), 41–59.

Osborn, T. L. (2012). How women represent women: Political parties, representation, and gender in the state legislatures. New York: Oxford University Press.

Palmer, B., & Simon, D. (2008). Breaking the political glass ceiling: Women and congressional elections (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Palmer, B., & Simon, D. (2012). Women & congressional elections: A century of change. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Pearson, K., & McGhee, E. (2013). What it takes to win: Questioning ‘gender neutral’ outcomes in U.S. House elections. Politics & Gender,9(4), 439–462.

Pettigrew, S., Owen, K., & Wanless, E. (2014). U.S. House primary election results (1956–2010). Harvard Dataverse, V3. https://doi.org/10.7910/dvn/26448.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2007). Ideology and congress. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Scammon, R. M., McGillivray, A. V., & Cook, R. (1990–2006). America votes 19-27: A handbook of contemporary American election statistics. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Political Psychology,35(2), 245–266.

Seltzer, R. A., Newman, J., & Leighton, M. V. (1997). Sex as a political variable: Women as candidates and voters in U.S. elections. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner.

Stone, W. J., & Maisel, L. S. (2003). The not-so-simple calculus of winning: Potential U.S. House candidates’ nomination and general election chances. Journal of Politics,65(4), 951–977.

Stonecash, J. M., Brewer, M. D., & Mariani, M. D. (2003). Diverging parties: Social change, realignment, and party polarization. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Streb, M. J., Burrell, B., Frederick, B., & Genovese, M. A. (2008). Social desirability effects and support for a female american president. Public Opinion Quarterly,72(1), 76–89.

Swers, M. L. (2014). Representing women’s interests in a polarized congress. In S. Thomas & C. Wilcox (Eds.), Women and elective office: past, present, and future (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Thomas, S., & Wilcox, C. (1998). Women and elective office: Past, present, and future. New York: Oxford University Press.

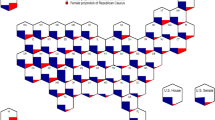

Thomsen, D. M. (2015). Why so few (republican) women? Explaining the partisan imbalance of women in the U.S. congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly,40(2), 295–323.

Thomsen, D. M., & Swers, M. L. (2017). Which women can run? Gender, partisanship, and candidate donor networks. Political Research Quarterly,70(2), 449–463.

Welch, S. (1985). Are women more liberal than men in the U.S. congress? Legislative Studies Quarterly,10(1), 125–134.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of the article were presented at the annual meetings of the Midwest Political Science Association and the Southern Political Science Association. I am grateful to the Dirksen Congressional Center and the Political Parity Project for their support of the data collection. I thank Rosalyn Cooperman, Melissa Deckman, Chris Faricy, Shana Gadarian, Andy Hall, Katherine Michelmore, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback. I am grateful to Spencer Piston for his comments on multiple drafts of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 4, 5, and 6 and Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Marginal effect of conservatism on primary election victory, by party. Note Values are calculated from the models in Table 1. The graphs show the marginal effect of ideological conservatism on primary election victory by party. The effect is positive for Republicans and negative for Democrats, but it does not differ for male and female candidates in either party

Marginal effect of conservatism on general election victory, by party. Note Values are calculated from the models in Table 1. The graphs show the marginal effect of ideological conservatism on general election victory by party. The effect is negative for Republicans and positive for Democrats, but it does not differ for male and female candidates in either party

The interactive effect of ideological conservatism and gender on primary and general election outcomes, by election year and party. Note The coefficients and 95% confidence intervals are calculated by year from the party-specific primary and general election models in Table 1. The interaction is significant only three times during this period (democratic primaries in 1984 and 1994 and republican general elections in 2006)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomsen, D.M. Ideology and Gender in U.S. House Elections. Polit Behav 42, 415–442 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9501-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9501-5