Abstract

Efforts to educate citizens about the candidates and issues at stake in elections are widespread. These include distributing voter guides describing candidates’ policy views and interactive tools conveying similar information. Do these voter education tools help voters identify candidates who share their policy views? We address this question by conducting survey experiments that randomly assign a nonpartisan voter guide, political party endorsements, a spatial map showing voters their own and the candidates’ ideological positions, or both a spatial map and party endorsements. We find that each type of information strengthens the relationship between voters’ policy views and those of the candidates they choose. These effects are largest for uninformed voters. When spatial maps and party endorsements send conflicting signals, many voters choose candidates with more similar policy views, against their party’s recommendation. These results contribute to debates about citizen competence and demonstrate the efficacy of practical efforts to inform electorates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Like Lupia (1994), we distinguish extensive fact-based information (encyclopedic) about candidates’ policy views from recommendations of knowledgeable information providers (shortcuts) that are easily acquired and allow voters to infer the consequences of their choices.

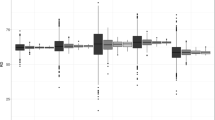

Previously, we examined the effects of a randomly-assigned voter guide relative to a control group receiving no information. Here, we build on that design by comparing the effects of two information shortcuts—party endorsements and spatial maps (both separately and together)—with the voter guide. We assess the effects of information on: (1) informed versus uninformed voters and (2) voters whose policy views and partisanship are aligned versus at odds.

The Republican Party’s webpage recommended “not Eric Mar” as a means of endorsing Lee without setting him up for a backlash from an overwhelmingly Democratic electorate.

202 of these letters were “returned to sender” by the Post Office.

The other 185 surveys were for a separate study. The number of observations in our analyses is 344 after excluding those who fail to indicate a party or a preference between Lee and Mar.

52% of respondents reported spending “1–5 minutes” viewing the guide, while another 36% spent longer. 95% found the voter guide to be “somewhat” or “very helpful.”

Bridging the profiles with these candidate and voter responses enhances the precision of the estimated ideal points, making it more likely that they reflect respondents’ true policy views.

See the OA for randomization checks and models that include control variables.

We also omit Ideology, as the variable Control * Ideology is coded to take the value of the respondent’s ideal point for respondents in the control group and zero otherwise.

We used the pscl package in R to analyze candidate and voter responses to 65 policy questions. We estimated a one-dimensional model with uninformative priors for all model parameters. The first dimension correctly classifies 75.1% of candidate and voter responses. Adding a second dimension did not improve the model (see the OA for details).

See the OA for models with an alternative measure of political knowledge.

A naïve spatial model with no partisan bias would predict that among respondents with ideal points equidistant between Mar and Lee, support for Lee would be 0.50. We observe support levels significantly below 0.50, suggesting some bias in favor of Mar, the incumbent.

We observe this effect despite the fact that our model includes Republicans and Independents. In the OA, we show that this effect is magnified when we exclude these respondents.

Specifically, the effect of receiving a voter education tool on the effect of Ideology among low-knowledge respondents is 0.39 higher than among high-knowledge respondents (p < 0.05). The difference in the effects of the voter guide (0.35), spatial map (0.36), and party + map (0.51) is also significant (p < 0.10) and the difference in the effect of party cues (0.31) nearly so.

References

Ahn, T. K., Huckfeldt, R., & Ryan, J. B. (2014). Experts, activists, and democratic politics: Are electorates self-educating?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arceneaux, K. (2008). Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior,30, 139–160.

Arceneaux, K., & Kolodny, R. (2009). Educating the least informed: Group endorsements in a grassroots campaign. American Journal of Political Science,53(4), 755–770.

Bafumi, J., & Herron, M. C. (2010). Leapfrog representation and extremism: A study of American voters and their members in congress. American Political Science Review,104(3), 519–542.

Bartels, L. M. (1996). Uninformed voters: Information effects in presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science,40, 194–230.

Bedolla, L. G., & Michelson, M. (2012). Mobilizing inclusion: Transforming the electorate through get-out-the-vote campaigns. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Black, D. (1948). On the rationale of group decision-making. Journal of Political Economy,56, 23–34.

Boudreau, C. (2009). Closing the gap: When do cues eliminate differences between sophisticated and unsophisticated citizens? Journal of Politics,71(3), 964–976.

Boudreau, C., Elmendorf, C. S., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2015a). Lost in space? Information shortcuts, spatial voting, and local government representation. Political Research Quarterly,68(4), 843–855.

Boudreau, C., Elmendorf, C. S., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2015b). Informing electorates via election law: An experimental study of partisan endorsements and nonpartisan voter guides in local elections. Election Law Journal,14(1), 2–23.

Boudreau, C., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2014). Informing the electorate? How party cues and policy information affect public opinion about initiatives. American Journal of Political Science,58(1), 48–62.

Bullock, J. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review,105(3), 496–515.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W., & Stokes, D. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Carpini, D., Michael, X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing public opinion in competitive democracies. American Political Science Review,101(4), 637–655.

Clinton, J. D., Jackman, S., & Rivers, D. (2004). The statistical analysis of roll call data. American Political Science Review,98, 355–370.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,85, 808–822.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent (pp. 206–261). New York: Free Press.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: HarperCollins.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth: Harcourt.

Enelow, J. M., & Hinich, M. J. (1984). The spatial theory of voting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garzia, D., Trechsel, A. H., Vassil, K., & Dinas, E. (2013). Indirect campaigning—Past, present and future of voting advice applications. In B. Grofman, A. H. Trechsel, & M. Franklin (Eds.), The Internet and Democracy in Global Perspective. New York: Springer.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Grofman, B., & Norrander, B. (1990). Efficient use of reference group cues in a single dimension. Public Choice,64, 213–227.

Jessee, S. A. (2010). Partisan bias, political information and spatial voting in the 2008 presidential election. Journal of Politics,72(2), 327–340.

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making,8(4), 407–424.

Kuklinski, J. H., Quirk, P. J., Jerit, J., & Rich, R. F. (2001). The political environment and citizen competence. American Journal of Political Science,45(2), 410–424.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science,45(4), 951–971.

Lodge, M., Steenbergen, M. R., & Brau, S. (1995). The responsive voter: Campaign information and the dynamics of candidate evaluation. American Political Science Review,89(2), 309–326.

Lupia, A. (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting behavior in california insurance reform elections. American Political Science Review,88, 63–76.

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they need to know?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McKelvey, R. D., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1986). Information, electoral equilibria, and the democratic ideal. Journal of Politics,8, 909–937.

Mummolo, J., & Peterson, E. (2017). How content preferences limit the reach of voting aids. American Politics Research,45(2), 159–185.

Nicholson, S. P. (2011). Dominating cues and the limits of elite influence. Journal of Politics,73(4), 1165–1177.

Petersen, M. B., Slothuus, R., & Togeby, L. (2010). Political parties and value consistency in public opinion formation. Public Opinion Quarterly,74(3), 530–550.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science,37, 472–496.

Rogers, T., & Middleton, J. (2015). Are ballot initiative outcomes influenced by the campaigns of independent groups? Political Behavior,37(3), 567–593.

Shor, B., & Rogowski, J. C. (2016). Ideology and the US congressional vote. Political Science Research and Methods. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.23.

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice: Explorations in political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., & Stiglitz, E. H. (2012). The reputational premium. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science,50, 755–769.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank participants in the “New Developments in the Study of Political Persuasion” conference at UC Irvine for valuable feedback. Thank you as well to the anonymous reviewers and the Editor for their excellent suggestions.

Funding

This research was generously funded by an Interdisciplinary Research Grant from the University of California, Davis. We are grateful to Danielle Joesten Martin for outstanding research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Additional information

Data and replication files are available on Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/U6YTI5).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boudreau, C., Elmendorf, C.S. & MacKenzie, S.A. Roadmaps to Representation: An Experimental Study of How Voter Education Tools Affect Citizen Decision Making. Polit Behav 41, 1001–1024 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9480-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9480-6