Abstract

To date, studies have consistently demonstrated associations between either neuropsychological deficits or neuroanatomical changes and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in aging. Only a limited number of studies have evaluated morphological brain changes and neuropsychological test performance concurrently in relation to IADL in this population. As a result, it remains largely unknown whether these factors independently predict functional outcome. The current systematic review intended to address this lack of information by reviewing the literature on older adults, incorporating studies that examined e.g., normal aging, but also stroke or dementia patients. A comprehensive search of databases (Pubmed, Embase, Medline, Web of Science, PsycINFO) and reference lists was performed, focusing on papers in the English language that examined the combined effect of neuropsychological and neuroanatomical factors on IADL in samples of adults with an average age above 50. In total, 58 potential articles were identified; 20 were included in the review. The results show that especially neuropsychological variables (primarily memory and executive functions) independently predict IADL. Although some unique predictive value of brain morphological changes, such as hippocampal atrophy, was found, support for the importance of white matter changes was limited. However, the results of the studies reviewed are diverse, and appear to be at least partially determined by the variables included. For example, studies were less likely to find an independent effect of cognition if they solely employed a cognitive screening instrument. This indicates that a structured examination of neuroanatomical and neuropsychological correlates of IADL in different patient populations is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Activities of daily living can be divided into basic activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). ADL consist of activities of self-maintenance such as feeding, dressing and toileting (Lawton and Brody 1969). IADL include complex behaviours of domestic functioning, such as food preparation, financial administration, housekeeping, use of telephone, responsibility for own medication, mode of transportation and shopping. In older adults with cognitive decline, such as dementia or vascular cognitive impairment, daily-living skills are often compromised. Moreover, even though normal aging is by definition characterized by intact IADL, some studies have illustrated that a lower level of education and an advanced age are associated with poorer functional status (Artero et al. 2001), as are chronic disease burden and lifestyle factors (Wang et al. 2002). Deficits in IADL have been linked to increased distress and a reduced quality of life in patients and their caregivers as well as an increased use of healthcare services (Hope et al. 1998; Vetter et al. 1999). Given the significant burden of functional impairments on patients, caregivers, and care providers, identifying factors that best predict future decline in daily functioning has important clinical implications. ADL and IADL can be affected by conditions that disturb mobility (e.g. stroke, amputation, arthritis) or visual and auditory perception. In the current review, the focus is on two other important correlates of IADL: neuropsychological and morphological brain changes.

Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), one of the most studied clinical populations, are commonly characterized by impairments in IADL. In the initial phases of AD, independent accomplishment of IADL is altered. The progressive decline later affects ADL as well (Gauthier et al. 1997). IADL functions require a greater complexity of neuropsychological organisation than ADL functions, and are therefore more likely to be sensitive to the early effects of cognitive decline (Pérès et al. 2008; Wicklund et al. 2007). In contrast, ADL, including tasks such as grooming, toileting, and feeding, correlate strongly with motor functioning and coordination (Boyle et al. 2002; Cahn et al. 1998).

In clinical practice, IADL impairments by definition determine the difference between the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia stage of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. As indicated in the previous section, IADL variables and neuropsychological deficits are closely related, but other determinants of IADL have also recently been identified. For example, neuroanatomical changes may act as a common pathway of deficits in both neuropsychological test performance and IADL, explaining their interrelationship. Previous studies have indeed illustrated a relationship between IADL and neuroanatomical outcome measures, such as white matter hyperintensities (Inzitari et al. 2009). A crucial question therefore is whether neuroanatomical and neuropsychological correlates are independently related to IADL. Most studies to date have focused on either neuropsychological or neuroanatomical correlates of IADL in isolation. The goal of this review is to examine the extent to which neuropsychological and neuroanatomical correlates independently predict IADL. In the next sections, we provide a short summary of the neuropsychological and neuroanatomical factors that have been identified as the most important correlates of impaired IADL, followed by a review of those studies that examined neuroanatomical and neuropsychological correlates of IADL concurrently.

The Relation between Neuropsychological Deficits and IADL

The first studies on this association showed that certain IADL activities are sensitive to early neuropsychological decline, and as such may be useful as predictors of future severe cognitive deterioration. Most earlier studies demonstrated a relation between global cognitive impairment, as assessed by screening instruments such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al. 1975), and measures of functional status (Reed et al. 1989; Skurla et al. 1988). Later studies (see next sections) distinguished between different cognitive domains and examined these either in isolation or in combination to IADL. Most of these studies were cross-sectional in nature; a handful of studies also examined longitudinal relationships.

Cross-Sectional Results

From a theoretical perspective, particularly executive functions may be relevant for IADL performance. These functions are generally defined as the abilities to perform complex, goal-directed, and self-serving behaviours (Brennan et al. 1997). Similarly, IADL are defined as complex, real-world adaptive human behaviours that require independence, volition, organizational ability, judgment and sequencing (Lawton 1988). Without appropriate executive control, individuals have difficulty appropriately initiating and completing IADL. Up until now, the majority of studies indeed point to strong associations between executive function and IADL. Previous work by Nadler et al. (1993) and Fogel and colleagues (Fogel 1994), for instance, demonstrated that measurements of executive functioning are reliable predictors of IADL in geriatric patients. More recent studies have confirmed these findings in other populations as well, including AD (Boyle et al. 2003a; Chen et al. 1998; Pereira et al. 2008; Razani et al. 2007; Senanarong et al. 2005; Stout et al. 2003), healthy community-dwelling elderly persons (Grigsby et al. 1998; Cahn-Weiner et al. 2000; Royall et al. 2004; Bell-McGinty et al. 2002), patients with Parkinson’s disease (Cahn et al. 1998) and elderly patients suffering from depression (Kiosses et al. 2000). These findings suggest that executive dysfunction may significantly affect the performance of complex activities that require goal-directed behaviour, organisation of an action and behavioural persistence.

In addition to executive dysfunction, a number of studies concluded that memory impairments are also associated with functional decline (Dunn et al. 1990; Goldstein et al. 1992; McCue et al. 1990; Richardson et al. 1995; Farias et al. 2004). Also studies that concurrently examined multiple cognitive domains, have demonstrated that memory and executive functioning are important correlates of IADL in AD (Farias et al. 2003; Matsuda and Saito 2005).

Longitudinal Results

Most of the studies examining the relationship between cognition and functional impairment are cross-sectional in nature, and have not examined how memory and executive function at baseline predict the rate of future decline in IADL. Cross-sectional studies therefore provide only limited insight into the course of decline in cognition and IADL function. Understanding the patterns of change in these two domains provides a better explanation of the course of dementia. Many early longitudinal studies that evaluated cognitive functioning and its relation with future disability have relied on global measures of cognition, such as the MMSE. For example, population-based longitudinal studies have shown that global measures of lower baseline cognitive function are associated with faster rates of functional decline and that they predict the development of future disability in IADL (Barberger-Gateau and Fabrigoule 1997; Royall et al. 2004; Schmeidler et al. 1998). More recently, Farias et al. (2009) examined the association between longitudinal changes in domain-specific cognitive functions and the decline in IADL. They found that changes in both memory and executive functions were independently associated with the rate of decline in IADL.

The Relation between Brain Morphological Changes and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Previous studies have revealed that neuropsychological functioning accounts for only a moderate proportion of variance in IADL (Reed et al. 1989; Nadler et al. 1993), indicating that other variables are important as well. For example, several studies have shown a significant association between IADL and white matter changes (WMC). Such findings have been reported in populations with predominantly subcortical ischemic vascular disease (SIVD) (Pohjasvaara et al. 2003, 2007) but also in patients with MCI (Yoon et al. 2013) or dementia (Moon et al. 2011; Park et al. 2011), as well as in community-dwelling older adults (Baune et al. 2009; Sonohara et al. 2008). A longitudinal study confirmed the important role of WMC in predicting future functional decline (Inzitari et al. 2009), by showing that older people with extensive age related changes in white matter are at a high risk of functional decline over the next three years.

In addition to WMC, some studies have highlighted the importance of gray matter atrophy in IADL (Yoshida et al. 2012). Hénon et al. (1998), for instance, found evidence that medial temporal lobe atrophy was associated with functional status in stroke patients. A recent longitudinal study demonstrated that parietal and temporal lobe atrophy at baseline predict worsening IADL impairment over time (Marshall et al. 2014). Nonetheless, up until now, most studies focused solely on WMC, and did not consider possible gray-matter alterations as important correlates of IADL.

Interim Summary and Goal of the Present Review

Overall, the aforementioned studies suggest that particularly executive function is related to IADL. Similarly, most studies indicate that WMC are associated with IADL. The extent to which these observations are independent is, however, unclear. The strong association that has been reported between executive function and WMC (Schmidt et al. 2011) indicates that WMC may mediate the relationship between executive function and IADL. In the same line, both hippocampal atrophy and memory function have been identified as correlates of IADL, but the extent to which these relationships are independent of one another, considering their strong association (Kaup et al. 2011), is largely unknown. Only a limited number of studies have examined the predictive value of neuropsychological and morphological variables for IADL concurrently. The main goal of this review is therefore to describe the present knowledge of the interrelationships between, and the unique contributions of, cognitive functioning and MRI findings in relation to IADL in elderly populations. We hypothesized that the effects of brain morphological changes and neuropsychological test performance on IADL are independent. In addition, we hypothesized that the underlying clinical condition (e.g., AD) affects this relationship. Here, we expected that neurocognitive deficits characteristic for a specific disease would emerge as the most important correlate of IADL, for example memory and/or hippocampal atrophy for AD and executive function and/or WMC in diseases with vascular pathology.

Methods

For this systematic review, an extensive literature search was conducted of online databases (Pubmed, Embase, Medline, Web of Science, and PsycINFO) until June 2015. The following inclusion criteria were employed: 1. The paper had to be published after 1988, based on the first population based studies concerning the relation between brain morphological changes, neuropsychological test performance and IADL in older adults; 2. The age of the study sample was restricted to a minimum of 50 years (on average), since from that age onwards significant changes in gray and white matter brain regions become apparent (Bartzokis et al. 2001; Walhovd et al. 2005); 3. The paper had to examine IADL in relation to neuropsychological and brain morphological changes concurrently. Only those articles explicitly addressing the question whether cognitive and/or neuropathological factors independently predict IADL in older adults were selected; 4. The paper had to be published in the English language; 5. The paper had to employ a validated measure of IADL, such as the Lawton & Brody IADL list, or had to refer to a previous study in which the list was validated; 6. Clinical diagnoses had to be made according to internationally-established guidelines.

Searches were conducted using (any truncated versions of) combinations of a keyword from each category: Category 1: Cognition (cognitive, cognition, memory, executive, visuospatial); Category 2: Imaging (MRI, magnetic resonance imaging, white matter, grey/gray matter, hippocampus); Category 3: IADL (activities of daily living, independence, functional impairment, functional decline, functional status, instrumental activities of daily living, IADL, ADL and vitality). IADL included the ability to perform the following tasks independently: food preparation, financial administration, housekeeping, use of telephone, responsibility for own medication, mode of transportation and shopping. The reference lists of all articles related to the study were screened, to identify additional relevant articles. Finally, in order to reduce the effect of a publication bias, several key authors of studies included in the review were contacted to inquire about the existence of unpublished study results on this topic.

EJO performed all initial searches and screened all abstracts of all articles that resulted from this search to identify potentially suitable papers; further selection of papers of interest for this study was conducted by EJO and JMO independently, and findings were discussed in a consensus meeting.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of all studies was rated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. This scale measures three types of outcomes for which a total of 9 stars can be given. These are the Selection criteria (4 stars maximum), the Comparability criteria (2 stars maximum), and the Outcome criteria (3 stars maximum). Criteria were adjusted such that the use of volumetric or validated visual rating scales was necessary to assess brain morphological changes, together with the use of standardized and validated instruments to measure neuropsychological test performance. Groups had to be matched with regard to age (first Comparability criterion), and educational attainment/intelligence estimate or sex (second Comparability criterion), or these factors had to be statistically controlled for in case of cross-sectional data, as they present important potential confounds of IADL. Since the studies included in this review examined cross-sectional/correlational data to answer the research question of whether MRI variables and neuropsychological scores independently predict IADL within specified study samples, also in longitudinal studies, the criteria were adjusted so that they covered quality ratings of these kinds of correlational studies (see Herzog et al. 2013). Both EJO and JMO independently rated these criteria, and consensus was reached through discussions.

Results

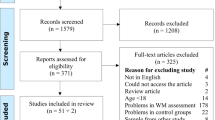

Based on the first screening of the titles and abstracts, the initial search resulted in 175 potential articles that were fully screened in order to identify potential studies for inclusion in this review, of which 58 explicitly referred to IADL in relation to cognitive and neuropathological deficits. A careful review of their reference lists did not identify any additional articles. A further detailed examination revealed that only 20 of these 58 studies explicitly examined the combined impact of cognitive and neuroanatomical factors on IADL, and met all specified inclusion criteria (Table 1). These studies focused on the following clinical populations: non-demented elderly people (n = 3), depressed elderly (depressed only: n = 2, depressed + non-depressed elderly: n = 2), vascular dementia patients (n = 3), MCI patients and elderly controls (n = 1), early AD and elderly controls (n = 2), elderly controls, MCI and dementia patients (n = 3), diabetic patients and elderly controls (n = 1), stroke patients with elderly controls (n = 1), MCI patients only (n = 1), and AD patients with cerebrovascular disease (n = 1). The authors that were contacted were not aware of unpublished study results; one unpublished dissertation was found, however, further inspection revealed that results from this dissertation were used as part of an already included article.

Studies that Found Unique Associations with Neuroanatomical Changes

Overall, of the 12 studies that examined the independent effects of WMC, four articles confirmed previous findings of significant associations between WMC and IADL. For example, Cahn et al. (1996) found that in patients with depression, subcortical hyperintensities accounted for an additional 18 % of the variance in IADL, in addition to age, depression severity, and neuropsychological test performance. Similar results have been reported in other populations such as patients with vascular dementia (Boyle et al. 2003b), AD patients with cerebrovascular disease (Chen et al. 2015), as well as in a longitudinal study in an elderly population (Inzitari et al. 2007).

Nine studies reported on the unique predictive value of hippocampal atrophy for IADL. Of these, four studies reported independent associations between hippocampal atrophy and IADL. Again, these findings pertain to a range of patient samples, including MCI and AD patients (Cahn-Weiner et al. 2007; Brown et al. 2011) as well as elderly people (Bennett et al. 2006; Verlinden et al. 2014).

Other studies reported unique associations with a neuroanatomical substrate that was reported in a single study only, such as orbitofrontal cortex volume (Taylor et al. 2003).

Studies that Found Unique Neuropsychological Correlates

The findings with regard to the unique neuropsychological correlates of IADL are somewhat homogeneous. Of the nine studies that examined the independent effects of executive function, in addition to other functions, six reported unique associations with IADL. (i.e., Bennett et al. 2006; Boyle et al. 2003b; 2004; Cahn-Weiner et al. 2007; Christman et al. 2010; Mok et al. 2004). Furthermore, out of eight studies that examined the independent effects of memory function, in addition to other functions, five studies found unique associations with IADL (i.e., Bennett et al. 2002, 2006; Brown et al. 2011; Cahn-Weiner et al. 2007; Marshall et al. 2014). Some studies found effects of other measures, such as spatial span and arithmetic ability (Griffith et al. 2010) or of tests that tap psychomotor speed (Brown et al. 2011; Christman et al. 2010; Marshall et al. 2014) or attention (Bennett et al. 2002, 2006; Stoeckel et al. 2013).

Since executive functions are strongly related to WMC, it is crucial to determine whether the effects of executive function are independent of those from WMC; the same applies to memory and hippocampal atrophy. Six studies examined WMC together with executive control (as independent measure, not as part of one overall cognitive domain score) in relation to IADL. Of these, four studies noted independent effects of executive function only, one study found contributions of both executive function and WMC, whereas one study found no effects of these variables at all. In the same line, four studies examined memory and hippocampal measures concurrently, three of which reported independent effects of both of these predictors, whereas the fourth study reported no effects of these variables at all.

Study that Reported Inconclusive Results

In a mixed group of healthy adults and early AD patients, Vidoni et al. (2010) demonstrated that impaired cognitive functioning was related to reduced gray matter volume in the medial frontal (AD patients) and in the middle frontal and precentral cortex (healthy group). According to the authors, this likely affects independent performance of IADL in part through a decline in associated executive aspects of functioning. The results suggest that cognitive function had both a strong direct effect on and mediated the influence of physical function on independence for those with AD. It is unclear, however, whether cognitive and neuroimaging correlates independently related to IADL.

Effects of Clinical Condition

Of all studies included in the review, four reported on patient groups with a significant underlying cerebrovascular pathology, five on patients with Alzheimer pathology (amnestic MCI and/or AD, without including controls in the analysis), three on patients with depression (apart from controls), and six on elderly populations (without including patients in the analysis). In this section, we specifically focus on white matter and hippocampal measures, together with memory and executive function as neuropsychological domains, as these were the most important predictors of IADL overall. An overview of the most important MRI correlates of IADL is depicted in Fig. 1, specific disease states in which certain MRI variables are associated with IADL are reported in the caption.

Overview of the main brain structures involved in IADL function; a) neocortical regions: middle frontal gyrus (blue) associated with IADL in non-demented older adults and AD patients, supramarginal gyrus (yellow) associated with IADL in AD, angular gyrus (red) associated in amnestic MCI and AD, inferior temporal gyrus (green) associated with IADL in AD; b) medial temporal lobe atrophy associated with impaired IADL function in non-demented older adults, MCI and AD (coronal T1-MRI showing the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in green boxes); c) subcortical white matter lesions associated with IADL in vascular dementia, older adults with depressive symptoms and non-demented older adults (red arrows on transversal FLAIR-MRI indicating frontal and occipital white matter hyperintensities)

In the studies that include patients with cerebrovascular pathology, three out of four found a unique effect of executive functioning on IADL, but only one out of four found a unique effect of underlying white matter pathology. One study found a unique effect of memory, but only two studies examined memory performance as an independent predictor in total; none of these studies examined hippocampal volume.

Of the five studies examining Alzheimer pathology, only one out of four studies that examined hippocampal volume found an independent effect on IADL. Two out of three studies found an effect of memory; two studies used executive function measures, but found no effect. None of these five studies measured white matter integrity.

None of the studies on clinical depression focused on independent measures of memory, executive function, or hippocampal volume. White matter integrity was examined in all three studies; only one reported an independent effect on IADL.

Finally, in six studies examining elderly populations, one out of four studies showed a unique effect of WMC whereas two out of three studies identified hippocampal volume as a unique correlate. Only two studies examined independent effects of memory and executive functioning, and only one reported that these cognitive functions independently relate to IADL.

The Effect of Methodology

Consensus was reached between both raters and, overall, methodological quality of the studies was judged to be sufficient (see supplementary Online Recourse 1). One study did not reach the cut-off point of 5 (out of 9) that has been used to determine whether the methodological quality is sufficient (Stubbs et al. 2013). Six studies obtained a score of 5, five a score of 6, four a score of 7, and four a score of 8. Nonetheless, significant methodological differences exist across studies, which may account for the heterogeneous findings. In the next section, we will discuss the following potential confounders in relation to the study outcomes: how IADL was measured (self-report, informant-based or performance-based), how brain morphological changes were quantified (through visual or volumetric measures), and how the neuropsychological assessment was conducted (brief or detailed).

The Effect of IADL Assessment

Of all studies included, six solely relied on self-report measures, nine used informant-based measures of IADL, two combined self-report with informant-based reports for their participants, two used performance-based indices of IADL, and one used informant-based IADL measures for their patients and self-report measures for their control group (see Table 1). The outcomes of the studies using self-report versus informant-based reports of IADL were comparable. In the seven studies that reported on correlates of self-report measures, five times (71.4 %) a unique effect of cognition was demonstrated, and four times (57.1 %) an independent effect of neuroimaging variables was reported. Of the 12 studies that reported correlates of informant-based IADL measures, these numbers were eight (66.7 %) and seven (58.3 %), respectively. At a more detailed level, no association was found between the type of IADL assessment and whether or not an effect of hippocampal atrophy, executive or memory deficits on IADL was found. The only exception was WMC, which were never related to IADL when self-report measures were used, whereas they were related to IADL in 50 % of the instances where studies relied on informant-reports. It should be noted, though, that informant-reports or performance-based indices of IADL were more likely employed in patients with pathological conditions such as stroke, MCI or dementia (83.3 % of the cases) compared to studies that solely focused on the elderly population, diabetic patients or depressed patients (54.5 % of all cases where cognitive and MRI correlates were considered).

The Effect of MRI Assessment

Nearly all studies employed volumetric measurements to quantify morphological changes in the brain. Visual scoring, if used, was mainly employed to assess white matter integrity. Out of a total of 12 studies, five used visual and seven volumetric assessment of WMC. For both assessment methods, two studies reported unique effects of WMC on IADL, whereas five (volumetric) and three (visual) did not.

The Effect of Neuropsychological Assessment

Several studies used a neuropsychological test battery to provide a detailed examination of cognitive functioning, tapping a wide array of functions such as memory, attention, executive functions, and psychomotor speed. Others, however, used a brief battery tapping some, but not all, of these functions, or even used a single broad cognitive screening instrument such as the MMSE. Further employment of cognitive outcome measures also differed between studies: some calculated a single cognitive outcome measure based on multiple neuropsychological tests, whereas others examined tasks/functions such as memory and executive function as independent constructs when examining associations with IADL.

To examine the effect of neuropsychological assessment, we made an distinction between: 1. Studies employing multiple neuropsychological tests tapping at least 3 distinct cognitive domains, 2. Studies conducting a brief neuropsychological examination, employing one or some neuropsychological tests and/or tapping less than 3 cognitive domains, and 3. Studies only using a screening instrument such as the MMSE. This resulted in six studies using a detailed and seven using a brief neuropsychological examination, and seven studies using a screening instrument. Of these studies, independent associations of cognition with IADL were noted for the majority of studies using detailed or brief neuropsychological examinations (both >65 %); for those studies using a screening instrument, only 42.9 % reported an independent association between this instrument and IADL.

Discussion

The main goal of the present review was to examine to what extent cognitive and brain morphological changes independently predict IADL. The majority of studies discussed in the present review demonstrate that performance on neuropsychological tests for the domains memory (62.5 % of studies that examined this function) and executive functioning (66.7 % of studies) are both associated with present IADL impairment and predictive of future decline in IADL; overall, 83.3 % of all studies (that explicitly reported the effect of cognition) demonstrated a unique effect of cognition on IADL. Neuroimaging markers, independent of cognitive function, were also associated with IADL, but to a lesser extent. In total, 44.4 % of studies examining this brain structure reported that hippocampal volume was associated with impairment in IADL, and 33.3 % of studies found WMC predictive of IADL; overall, 60.0 % of the studies reported an independent effect of brain neuroanatomical changes. Whereas both these factors – cognitive dysfunction and brain morphological changes – are important and independent indicators of IADL, cognitive functioning appears to be a stronger predictor than morphological changes in the brain. Finally, whereas some unique effects of hippocampal atrophy were noted, that extended beyond the effects of episodic memory, WMC appear less predictive, particularly once executive functioning is simultaneously examined.

One possible explanation why episodic memory plays an important role in IADL is that our ability to fulfil future actions is strongly dependent on episodic memory processes (Einstein et al. 1992). Alternatively, a potential explanation is that episodic memory impairment/hippocampal atrophy merely reflects a disease severity effect in MCI and AD patients, in that more severe hippocampal atrophy/memory impairments and severe IADL impairments are both indicative of a more advanced disease state. Similarly, the association with hippocampal volume in healthy aging may reflect preclinical neuropathological changes as the result of neurodegenerative disease, such as AD (Apostolova et al. 2010; Den Heijer et al. 2006). Thus, the association between memory and hippocampal atrophy and IADL functioning may predominantly reflect an underlying neuropathological process rather than highlight a unique role of the hippocampus or memory function. Further studies that compare multiple, yet homogeneous, clinical populations that vary in the level of the extent to which memory and hippocampal volume are affected are needed in order to answer this question.

With respect to executive dysfunction, planning, sequencing capacity, and monitoring are prerequisites for successful IADL performance. In line, impaired executive processes may provide a possible explanation about how WMC may lead to impairment in IADL. That is, WMC may result in impaired executive function relevant for IADL due to disruption of frontal subcortical circuits (Cahn et al. 1996; Kiosses et al. 2000). However, we found that studies that concurrently examined the effects of WMC and executive functioning most consistently reported independent effects of executive function, but not WMC, on IADL. This suggests that the impairment in IADL associated with WMC is mediated by an impairment in executive function.

Although our review indicates that both neuropsychological and neuroanatomical changes may be important independent correlates of IADL, some limitations need to be addressed. Firstly, some studies reported a composite measure of cognitive functioning including several cognitive domains, making it impossible to detect the unique contribution of each domain in relation to IADL (Inzitari et al. 2007; Cahn et al. 1996; Vidoni et al. 2010). These studies therefore prohibit drawing firm conclusions regarding specific cognitive domains that are relevant for IADL.

Secondly, it is crucial to realize that the study outcome is largely determined by the variables that were included in the respective studies. For example, some studies only used the MMSE as the cognitive correlate (Steffens et al. 2002; Taylor et al. 2003; Hybels et al. 2014; Verlinden et al. 2014; Kochan et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2015), whereas others employed extensive neuropsychological test batteries (e.g., Cahn et al. 1996; Bennett et al. 2002; Christman et al. 2010). It is unclear whether MMSE scores (that are known to have little sensitivity for executive dysfunction or memory) will still be significantly associated with IADL once other functions, such as executive control, are considered as well. Patients with high education levels may also perform near ceiling level, which makes the MMSE inappropriate as a measure of cognitive functioning in highly-educated subjects (Franco-Marina et al. 2010). These shortcomings are substantiated by our examination of the outcomes in relation to the neuropsychological examination; unique associations with IADL were less often reported when cognitive screening instruments were used, compared to studies that employed more detailed neuropsychological examinations.

Similarly, with respect to potential morphological correlates, a significant portion of studies focused solely on WMC in relation to IADL (Boyle et al. 2004; Hybels et al. 2014; Pantoni et al. 2006; Inzitari et al. 2007). Likewise, the unique contribution of variables that are strongly interrelated and also predict IADL, such as executive function and WMC, or hippocampal atrophy and memory, needs specification in future studies. Most studies found either an independent effect of morphological changes or an independent effect of neuropsychological correlates. Only a small number of studies found concurrent independent effects of both potential correlates, and only few identified independent contributions of interrelated predictors, such as concurrent independent effects of WMC and executive function.

Even though we found evidence that executive function problems, and at one occasion WMC, predicted IADL in patients with vascular pathology, hippocampal pathology was not examined in these patients. However, hippocampal atrophy is a common observation in patients with vascular cognitive impairment (Liu et al. 2014, although the atrophy is potentially less severe than in AD, see Kim et al. 2015) and is therefore likely to predict IADL in this population as well. In turn, none of the studies in patients with Alzheimer pathology examined whether WMC played an important role, despite the fact that WMC are also commonly observed in AD patients (Burton et al. 2006; Kandiah et al. 2015). Related to this, although true neurocognitive deficits are likely present in neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, factors such a lack of motivation may explain such deficits in depressed patients (Kiosses and Alexopoulos 2005). Whether this holds true for the current findings is unclear, as two studies have demonstrated independent effects of brain morphological changes, namely of white matter pathology (Cahn et al. 1996) and orbitofrontal cortex volume (Taylor et al. 2003), on IADL. This suggests that much remains to be done in identifying those variables that most strongly predict IADL in different clinical populations.

One of the reasons for the mixed results may relate to the method of reporting on IADL questionnaires. For example, Tan et al. (2009) found that executive function was more strongly associated with informant-reports than self-reports in MCI. In addition, informant-reports of IADL were able to accurately distinguish levels of functional independence, whereas self-report measurements could not (Farias et al. 2005). In particular, when IADL variables are obtained from self-reports in depressed individuals, results may not represent true limitations, as a depressed mood may influence the perception of functional impairment. Furthermore, most of the studies reviewed used questionnaire-based assessment and only two studies used performance-based assessments. Questionnaire-based and performance-based assessment of IADL may call upon different executive problems or processes (Cahn-Weiner et al. 2002). Consequently, cognitive predictors may vary as a result of the type of IADL assessment protocol.

In addition, it is possible that the type or format of the IADL questionnaire used may influence the cognitive variables which are necessary to perform the task. Although nine studies used the same IADL subscale of Lawton and Brody, with which the remaining questionnaires show overlap, there are also differences in the type of IADL items being assessed. For instance, some of the questionnaires include items such as being able to talk about current events, a tendency to dwell in the past, or paying attention and understanding while reading or watching television. Moreover, a variation is present in the way questions about IADL items are formulated. Whereas one questionnaire may inquire more superficially about performing financial administration, the other will examine the same task more thoroughly. The interpretation of the relation found between cognitive variables and IADL is further complicated by a variety in formats of items to be rated. The scales differ in their range of rating points between dependence and independence in a task, which make them more or less sensitive to detect functional decline. In sum, a number of factors related to the questionnaires reviewed influence the variance in prediction of IADL performance.

Some discussion about the methodological quality of the included studies in this review is in place. The methodological quality of the studies included was rated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. Overall, the quality of nineteen studies was judged to be sufficient; only one study did not reach the cut-off point of 5. Nevertheless, the quality of the studies reviewed could certainly be improved given the fact that eleven studies achieved just a score of 5 or 6. Moreover, the possibility of a publication bias cannot be ruled out. In order to take into account the effect of a publication bias, the majority of the key authors of the studies included were contacted to inquire about the existence of unpublished study results on this topic. Only three authors responded to our request; none of these authors were aware of unpublished studies. Furthermore, considering the small number of included studies, we could not be too strict regarding the inclusion versus exclusion criteria, for example by including only those studies with a comprehensive neuropsychological examination.

Clearly, research examining the combined impact of cognitive and neuropathological factors on instrumental activities of daily living is still in its infancy. Additional research is needed to clarify the predictors of functional impairment in elderly people and to establish the relative contribution of specific neuropsychological and morphological deficits. Given the impact of pre-frontal dysfunction and hippocampal atrophy on IADL, thorough evaluations of executive and memory dysfunction in patients seen in memory clinics, combined with neuroimaging, may assist in identifying individuals at risk for functional disability and provide important information regarding treatment planning.

To summarize, the present review provides clear evidence that executive function and memory, together with hippocampal atrophy – and to a lesser extent white matter changes – play crucial roles in maintaining an independent lifestyle. Studies systematically examining these neuropsychological and morphological factors concurrently in different patient populations are needed to identify the uniqueness of these potential correlates for IADL. In addition, longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether these cognitive and morphological deficits are actually causally related to disability. If so, interventions to treat cerebrovascular disease and to prevent its worsening may have a significant impact on functional status.

References

Apostolova, L. G., Mosconi, L., Thompson, P. M., Green, A. E., Hwang, K. S., Ramirez, A., et al. (2010). Subregional hippocampal atrophy predicts alzheimer’s dementia in the cognitively normal. Neurobiology of Aging, 31(7), 1077–1088.

Artero, S., Touchon, J., & Ritchie, K. (2001). Disability and mild cognitive impairment: a longitudinal population-based study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(11), 1092–1097.

Barberger-Gateau, P., & Fabrigoule, C. (1997). Disability and Cognitive Impairment in the Elderly. Disability and Rehabilitation, 19(5), 175–193.

Bartzokis, G., Beckson, M., Lu, P. H., Nuechterlein, K. H., Edwards, N., & Mintz, J. (2001). Age-related changes in frontal and temporal lobe volumes in men: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 461–465.

Baune, B. T., Schmidt, W. P., Roesler, A., & Berger, K. (2009). Functional consequences of subcortical white matter lesions and mri-defined brain infarct in an elderly general population. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 22(4), 266–273.

Bell-McGinty, S., Podell, K., Franzen, M., Baird, A. D., & Williams, M. J. (2002). Standard measures of executive function in predicting instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(9), 828–834.

Bennett, H. P., Corbett, A. J., Gaden, S., Grayson, D. A., Kril, J. J., & Broe, G. A. (2002). Subcortical vascular disease and functional decline: a 6-year predictor study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(12), 1969–1977.

Bennett, H. P., Piguet, O., Grayson, D. A., Creasey, H., Waite, L. M., Lye, T., et al. (2006). Cognitive, extrapyramidal, and magnetic resonance imaging predictors of functional impairment in nondemented older community dwellers: the Sydney older person study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(1), 3–10.

Boyle, P. A., Cohen, R. A., Paul, R., Moser, D., & Gordon, N. (2002). Cognitive and motor impairments predict functional declines in patients with vascular dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(2), 164–169.

Boyle, P. A., Malloy, P. F., Salloway, S., Cahn-Weiner, D. A., Cohen, R., & Cummings, J. L. (2003a). Executive dysfunction and apathy predict functional impairment in alzheimer disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(2), 214–221.

Boyle, P. A., Paul, R. H., Moser, D. J., & Cohen, R. A. (2004). executive impairments predict functional declines in vascular dementia. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 18(1), 75–82.

Boyle, P. A., Paul, R., Moser, D., Zawacki, T., Gordon, N., & Cohen, R. (2003b). Cognitive and neurologic predictors of functional impairment in vascular dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(1), 103–106.

Brennan, M., Welsh, M. C., & Fisher, C. B. (1997). Aging and executive function skills: an examination of a community-dwelling older adult population. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 84(3), 1187–1197.

Brown, P. J., Devanand, D. P., Liu, X., & Caccappolo, E. (2011). Functional impairment in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(6), 617–626.

Burton, E. J., McKeith, I. G., Burn, D. J., Firbank, M. J., & O’Brien, J. T. (2006). Progression of white matter hyperintensities in alzheimer disease, dementia with lewy bodies, and parkinson disease dementia: a comparison with normal aging. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(10), 842–849.

Cahn, D. A., Malloy, P. F., Salloway, S., Rogg, J., Gillard, E., Kohn, R., et al. (1996). Subcortical hyperintensities on mri and activities of daily living in geriatric depression. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 8(4), 404–411.

Cahn, D. A., Sullivan, E. V., Shear, P. K., Pfefferbaum, A., Heit, G., & Silverberg, G. (1998). differential contributions of cognitive and motor component processes to physical and instrumental activities of daily living in parkinson’s disease. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 13(7), 575–583.

Cahn-Weiner, D. A., Boyle, P. A., & Malloy, P. F. (2002). Tests of executive function predict instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling older individuals. Applied Neuropsychology, 9(3), 187–191.

Cahn-Weiner, D. A., Farias, S. T., Julian, L., Harvey, D. J., Kramer, J. H., Reed, B. R., et al. (2007). Cognitive and neuroimaging predictors of instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 13(5), 747–757.

Cahn-Weiner, D. A., Malloy, P. F., Boyle, P. A., Marran, M., & Salloway, S. (2000). Prediction of functional status from neuropsychological tests in community-dwelling elderly individuals. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 14(2), 187–195.

Chen, S. T., Sultzer, D. L., Hinkin, C. H., Mahler, M. E., & Cummings, J. L. (1998). Executive dysfunction in alzheimer’s disease: association with neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional impairment. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 10(4), 426–432.

Chen, Y. K., Xiao, W. M., Li, W. Y., Liu, Y. L., Li, W., Qu, J. F., et al. (2015). Neuroimaging indicators of the performance of instrumental activities of daily living in alzheimer’s disease combined with cerebrovascular disease. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 15(5), 588–593.

Christman, A. L., Vannorsdall, T. D., Pearlson, G. D., Hill-Briggs, F., & Schretlen, D. J. (2010). Cranial volume, mild cognitive deficits, and functional limitations associated with diabetes in a community sample. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 25(1), 49–59.

Den Heijer, T., Geerlings, M. I., Hoebeek, F. E., Hofman, A., Koudstaal, P. J., & Breteler, M. M. (2006). Use of hippocampal and amygdalar volumes on magnetic resonance imaging to predict dementia in cognitively intact elderly people. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(1), 57–62.

Dunn, E. J., Searight, H. R., Grisso, T., Margolis, R. B., & Gibbons, J. L. (1990). The relation of the halstead-reitan neuropsychological battery to functional daily living skills in geriatric patients. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 5(2), 103–117.

Einstein, G. O., Holland, L. J., McDaniel, M. A., & Guynn, M. J. (1992). Age-related deficits in prospective memory: the influence of task complexity. Psychology and Aging, 7(3), 471–478.

Farias, S. T., Cahn-Weiner, D. A., Harvey, D. J., Reed, B. R., Mungas, D., Kramer, J. H., et al. (2009). Longitudinal changes in memory and executive functioning are associated with longitudinal change in instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 23(3), 446–461.

Farias, S. T., Harrell, E., Neumann, C., & Houtz, A. (2003). The relationship between neuropsychological performance and daily functioning in individuals with alzheimer’s disease: ecological validity of neuropsychological tests. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 18(6), 655–672.

Farias, S. T., Mungas, D., & Jagust, W. (2005). Degree of discrepancy between self and other-reported everyday functioning by cognitive status: dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy elders. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(9), 827–834.

Farias, S. T., Mungas, D., Reed, B., Haan, M. N., & Jagust, W. J. (2004). Everyday functioning in relation to cognitive functioning and neuroimaging in community-dwelling hispanic and non-hispanic older adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 10(3), 342–354.

Fogel, B. S. (1994). The Significance of frontal system disorders for medical practice and health policy. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 6(4), 343–347.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). "Mini-mental state". a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198.

Franco-Marina, F., García-González, J. J., Wagner-Echeagaray, F., Gallo, J., Ugalde, O., Sánchez-García, S., et al. (2010). The Mini-mental state examination revisited: ceiling and floor effects after score adjustment for educational level in an aging mexican population. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 72–81.

Gauthier, S., Gélinas, I., & Gauthier, L. (1997). Functional disability in alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics, 9(S1), 163–165.

Goldstein, G., McCue, M., Rogers, J., & Nussbaum, P. D. (1992). Diagnostic differences in memory test based predictions of functional capacity in the elderly. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 2(4), 307–317.

Griffith, H. R., Stewart, C. C., Stoeckel, L. E., Okonkwo, O. C., den Hollander, J. A., Martin, R. C., et al. (2010). Magnetic resonance imaging volume of the angular gyri predicts financial skill deficits in people with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(2), 265–274.

Grigsby, J., Kaye, K., Baxter, J., Shetterly, S. M., & Hamman, R. F. (1998). Executive cognitive abilities and functional status among community-dwelling older persons in the san luis valley health and aging study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 46(5), 590–596.

Hénon, H., Pasquier, F., Durieu, I., Pruvo, J. P., & Leys, D. (1998). Medial temporal lobe atrophy in stroke patients: relation to pre-existing dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 65(5), 641–647.

Herzog, R., Álvarez-Pasquin, M. J., Díaz, C., Del Barrio, J. L., Estrada, J. M., & Gil, Á. (2013). Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13, 154.

Hope, T., Keene, J., Gedling, K., Fairburn, C. G., & Jacoby, R. (1998). Predictors of institutionalization for people with dementia living at home with a carer. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(10), 682–690.

Hybels, C. F., Pieper, C. F., Landerman, L. R., Payne, M. E., & Steffens, D. C. (2014). Vascular lesions and functional limitations among older adults: does depression make a difference? International Psychogeriatrics, 26(9), 1501–1509.

Inzitari, D., Pracucci, G., Poggesi, A., Carlucci, G., Barkhof, F., Chabriat, H., et al. (2009). Changes in white matter as determinant of global functional decline in older independent outpatients: three year follow-up of ladis (leukoaraiosis and disability) study cohort. British Medical Journal, 339, b2477.

Inzitari, D., Simoni, M., Pracucci, G., Poggesi, A., Basile, A. M., Chabriat, H., et al. (2007). Risk of rapid global functional decline in elderly patients with severe cerebral age-related white matter changes: the LADIS study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167(1), 81–88.

Kandiah, N., Chander, R. J., Ng, A., Wen, M. C., Cenina, A. R., & Assam, P. N. (2015). Association between white matter hyperintensity and medial temporal atrophy at various stages of alzheimer’s disease. European Journal of Neurology, 22(1), 150–155.

Kaup, A. R., Mirzakhanian, H., Jeste, D. V., & Eyler, L. T. (2011). A review of the brain structure correlates of successful cognitive aging. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 23(1), 6–15.

Kim, G. H., Lee, J. H., Seo, S. W., Kim, J. H., Seong, J. K., Ye, B. S., et al. (2015). Hippocampal volume and shape in pure subcortical vascular dementia. Neurobiology of Aging, 36(1), 485–491.

Kiosses, D. N., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2005). IADL functions, cognitive deficits, and severity of depression: a preliminary study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(3), 244–249.

Kiosses, D. N., Alexopoulos, G. S., & Murphy, C. (2000). Symptoms of striatofrontal dysfunction contribute to disability in geriatric depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(11), 992–999.

Kochan, N. A., Breakspear, M., Valenzuela, M., Slavin, M. J., Brodaty, H., Wen, W., et al. (2011). Cortical responses to a graded working memory challenge predict functional decline in mild cognitive impairment. Biological Psychiatry, 70(2), 123–130.

Lawton, M. P. (1988). Scales to measure competence in everyday activities. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 24(4), 609–614.

Lawton, M. P., & Brody, E. M. (1969). Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3), 179–186.

Liu, C., Li, C., Gui, L., Zhao, L., Evans, A. C., Xie, B., et al. (2014). The pattern of brain gray matter impairments in patients with subcortical vascular dementia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 341(1–2), 110–118.

Marshall, G. A., Lorius, N., Locascio, J. J., Hyman, B. T., Rentz, D. M., Johnson, K. A., et al. (2014). Regional cortical thinning and cerebrospinal biomarkers predict worsening daily functioning across the alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 41(3), 719–728.

Matsuda, O., & Saito, M. (2005). Functional competency and cognitive ability in mild alzheimer’s disease: relationship between adl assessed by a relative/carer-rated scale and neuropsychological performance. International Psychogeriatrics, 17(2), 275–288.

McCue, M., Rogers, J. C., & Goldstein, G. (1990). Relationship between neuropsychological and functional assessment in elderly neuropsychiatric patients. Rehabilitation Psychology, 35(2), 91–99.

Mok, V. C., Wong, A., Lam, W. W., Fan, Y. H., Tang, W. K., Kwok, T., et al. (2004). Cognitive impairment and functional outcome after stroke associated with small vessel disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 75(4), 560–566.

Moon, S. Y., Na, D. L., Seo, S. W., Lee, J. Y., Ku, B. D., Kim, S. Y., et al. (2011). Impact of white matter changes on activities of daily living in mild to moderate dementia. European Neurology, 65(4), 223–230.

Nadler, J. D., Richardson, E. D., Malloy, P. F., Marran, M. E., & Hosteller Brinson, M. E. (1993). The ability of the dementia rating scale to predict everyday functioning. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 8(5), 449–460.

Pantoni, L., Poggesi, A., Basile, A. M., Pracucci, G., Barkhof, F., Chabriat, H., et al. (2006). Leukoaraiosis predicts hidden global functioning impairment in nondisabled older people: the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis and Disability in the Elderly) study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(7), 1095–1101.

Park, K. H., Lee, J. Y., Na, D. L., Kim, S. Y., Cheong, H. K., Moon, S. Y., et al. (2011). Different associations of periventricular and deep white matter lesions with cognition, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and daily activities in dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 24(2), 84–90.

Pereira, F. S., Yassuda, M. S., Oliveira, A. M., & Forlenza, O. V. (2008). Executive dysfunction correlates with impaired functional status in older adults with varying degrees of cognitive impairment. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(6), 1104–1115.

Pérès, K., Helmer, C., Amieva, H., Orgogozo, J. M., Rouch, I., Dartigues, J. F., et al. (2008). Natural history of decline in instrumental activities of daily living performance over the 10 years preceding the clinical diagnosis of dementia: a prospective population-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(1), 37–44.

Pohjasvaara, T. I., Jokinen, H., Ylikoski, R., Kalska, H., Mäntylä, R., Kaste, M., et al. (2007). White matter lesions are related to impaired instrumental activities of daily living poststroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, 16(6), 251–258.

Pohjasvaara, T., Mäntylä, R., Ylikoski, R., Kaste, M., & Erkinjuntti, T. (2003). Clinical features of mri-defined subcortical vascular disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 17(4), 236–242.

Razani, J., Casas, R., Wong, J. T., Lu, P., Alessi, C., & Josephson, K. (2007). Relationship between executive functioning and activities of daily living in patients with relatively mild dementia. Applied Neuropsychology, 14(3), 208–214.

Reed, B. R., Jagust, W. J., & Seab, J. P. (1989). Mental status as a predictor of daily function in progressive dementia. The Gerontologist, 29(6), 804–807.

Richardson, E. D., Nadler, J. D., & Malloy, P. F. (1995). Neuropsychologic prediction of performance measures of daily living skills in geriatric patients. Neuropsychology, 9(4), 565–572.

Royall, D. R., Palmer, R., Chiodo, L. K., & Polk, M. J. (2004). Declining executive control in normal aging predicts change in functional status: the Freedom house study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(3), 346–352.

Schmeidler, J., Mohs, R. C., & Aryan, M. (1998). Relationship of disease severity to decline on specific cognitive and functional measures in alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 12(3), 146–151.

Schmidt, R., Grazer, A., Enzinger, C., Ropele, S., Homayoon, N., Pluta-Fuerst, A., et al. (2011). MRI-detected white matter lesions: do they really matter? Journal of Neural Transmission, 118(5), 673–681.

Senanarong, V., Poungvarin, N., Jamjumras, P., Sriboonroung, A., Danchaivijit, C., Udomphanthuruk, S., et al. (2005). Neuropsychiatric symptoms, functional impairment and executive ability in thai patients with alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics, 17(1), 81–90.

Skurla, E., Rogers, J. C., & Sunderland, T. (1988). Direct assessment of activities of daily living in alzheimer’s disease. a controlled study. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 36(2), 97–103.

Sonohara, K., Kozaki, K., Akishita, M., Nagai, K., Hasegawa, H., Kuzuya, M., et al. (2008). White matter lesions as a feature of cognitive impairment, low vitality and other symptoms of geriatric syndrome in the elderly. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 8(2), 93–100.

Steffens, D. C., Bosworth, H. B., Provenzale, J. M., & MacFall, J. R. (2002). Subcortical white matter lesions and functional impairment in geriatric depression. Depression and Anxiety, 15(1), 23–28.

Stoeckel, L. E., Stewart, C. C., Griffith, H. R., Triebel, K., Okonkwo, O. C., den Hollander, J. A., et al. (2013). Brain Imaging and Behavior, 7(3), 282–292.

Stout, J. C., Wyman, M. F., Johnson, S. A., Peavy, G. M., & Salmon, D. P. (2003). Frontal behavioral syndromes and functional status in probable alzheimer disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(6), 683–686.

Stubbs, B., Binnekade, T. T., Soundy, A., Schofield, P., Huijnen, I. P., & Eggermont, L. H. (2013). Are older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain less active than older adults without pain? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Medicine, 14(9), 1316–1331.

Tan, J. E., Hultsch, D. F., & Strauss, E. (2009). Cognitive abilities and functional capacity in older adults: results from the modified scales of independent behavior-revised. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 23(3), 479–500.

Taylor, W. D., Steffens, D. C., McQuoid, D. R., Payne, M. E., Lee, S. H., Lai, T. J., et al. (2003). Smaller orbital frontal cortex volumes associated with functional disability in depressed elders. Biological Psychiatry, 53(2), 144–149.

Verlinden, V. J., van der Geest, J. N., de Groot, M., Hofman, A., Niessen, W. J., van der Lugt, A., et al. (2014). Structural and microstructural brain changes predict impairment in daily functioning. The American Journal of Medicine, 127(11), 1089–1096.

Vetter, P. H., Krauss, S., Steiner, O., Kropp, P., Möller, W. D., Moises, H. W., et al. (1999). Vascular dementia versus dementia of alzheimer’s type: do they have differential effects on caregivers’ burden? Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 54(2), 93–98.

Vidoni, E. D., Honea, R. A., & Burns, J. M. (2010). Neural correlates of impaired functional independence in early alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 19(2), 517–527.

Walhovd, K. B., Fjell, A. M., Reinvang, I., Lundervold, A., Dale, A. M., Eilertsen, D. E., et al. (2005). Effects of age on volumes of cortex, white matter and subcortical structures. Neurobiology of Aging, 26(9), 1261–1270.

Wang, L., van Belle, G., Kukull, W. B., & Larson, E. B. (2002). Predictors of functional change: a longitudinal study of nondemented people aged 65 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(9), 1525–1534.

Wicklund, A. H., Johnson, N., Rademaker, A., Weitner, B. B., & Weintraub, S. (2007). Profiles of decline in activities of daily living in non-alzheimer dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 21(1), 8–13.

Yoon, B., Shim, Y. S., Kim, Y. D., Lee, K. O., Na, S. J., Hong, Y. J., et al. (2013). Correlation between instrumental activities of daily living and white matter hyperintensities in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: results of a cross-sectional study. Neurological Sciences, 34(5), 715–721.

Yoshida, D., Shimada, H., Makizako, H., Doi, T., Ito, K., Kato, T., et al. (2012). the relationship between atrophy of the medial temporal area and daily activities in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(5), 423–429.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to research, authorship and publication of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Overdorp, E.J., Kessels, R.P.C., Claassen, J.A. et al. The Combined Effect of Neuropsychological and Neuropathological Deficits on Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Older Adults: a Systematic Review. Neuropsychol Rev 26, 92–106 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-015-9312-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-015-9312-y