Abstract

The existence of negative descriptions denoting events is controversial in the literature, since it implies enriching the semantic ontology with negative events. The goal of this article is to argue that the readings that have been called ‘negative events’—in contrast to sentential negation reading—should be analysed as inhibited eventualities. We will argue that the inhibited eventuality reading emerges when negation scopes over the verbal domain. Sentential negation, in contrast, scopes above the existential closure of the event variable. We will implement the analysis in a framework where the verbal domain combines symbolic objects that yield partial event-descriptions. These descriptions do not entail the existence of a Davidsonian eventuality with time and world parameters until they transition to the aspectual level. We will show that an analysis on these terms can capture the empirical properties of non-sentential negation without the need to propose negative events as objects in the ontology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unless otherwise noted, the data in this paper were elicited from 25 native speakers whose intuitions are reported to belong to different varieties of European Spanish. Namely, they stem from Andalucía, Asturias, Catalunya, Castilla La Mancha, Castilla y León, Madrid and the Basque Country. Their intuitions have, additionally, been checked with two speakers from Perú, and one speaker from México, but sufficient data about Latin American varieties of Spanish is lacking.

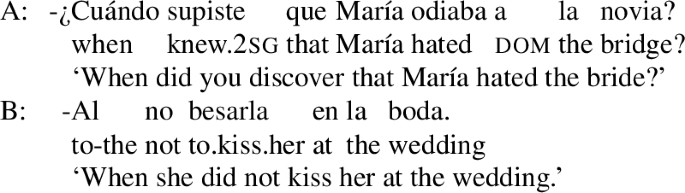

It is of course clear that there are pragmatic conditions on the felicitousness of this type of perception report. There are many instances of María not kissing the bride where the utterance in (1) is not felicitous—for instance, when María is sleeping at her place. This article will abstract away from the pragmatic conditions, however, instead concentrating on the syntactic and semantic conditions of sentences such as (1). As we will see in Sect. 3.3, there are argument structure restrictions on inhibited eventualities that have no obvious explanation in pragmatic terms.

See Cooper (1997:12–13) on the claim that some structures that license the inhibited event reading in English do not produce grammatical results in Swedish, for instance.

A note is in order with respect the term ‘eventuality.’ We use this term in the same sense as Bach (1986), that is, to refer to eventive predicates as well as to stative predicates. In Sect. 3.2, we will focus on the aspectual properties of inhibited eventualities and discuss if they denote events (Cooper 1997; Przepiórkowski 1999; Weiser 2008; Arkadiev 2015, 2016) or states, as has been argued by a number of authors (Bennett and Partee 1972; Dowty 1979; Verkuyl 1993; de Swart and Molendijk 1999).

As the careful reader will note, we are appealing to an inhibited eventuality in order to describe the interpretation of (2b) for expository reasons. The same applies throughout this section. For now, it suffices to note that (2a) and (2b) receive different readings. We will provide a more detailed discussion of the semantic object denoted by the reading in (2b) in Sect. 3.

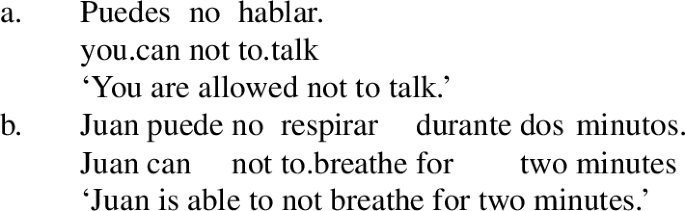

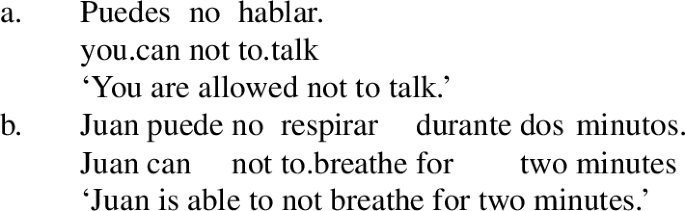

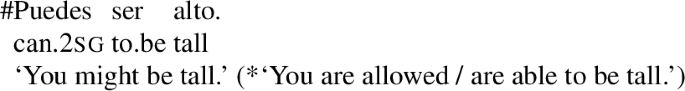

We assume here Picallo’s (1990) proposal that deontic modals are introduced lower than epistemic modals, close enough to the verbal complex so that they can still be sensitive to the argumental entailments of the external argument—hence the informal term ‘root modal’ that is sometimes used in the literature. The picture shown in (3) is also found with the other class of auxiliaries typically classified as root modals, dynamic modals: cf. Juan sabe no meterse en líos ‘lit. Juan knows not to.get into trouble, Juan knows how not to get into trouble.’

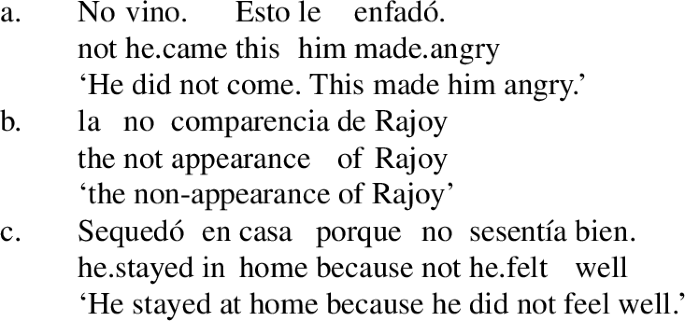

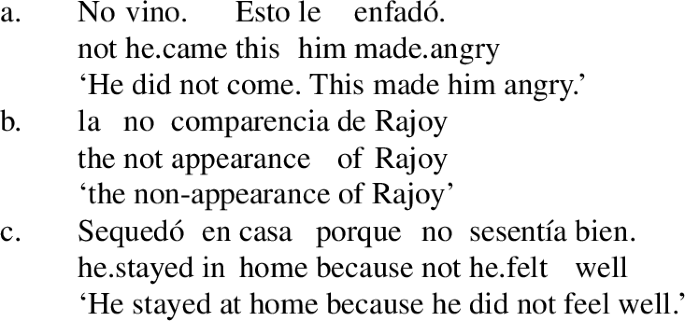

We will not discuss some of the arguments offered in the literature because they have been interpreted by other authors as compatible with an analysis in terms of facts. In particular, we exclude the following tests: the anaphoric reference to a negative sentence (see (ia)), the existence of nominal phrases such as the one in (ib), and the possibility of a negative clause having causal efficacy (see (ic)). As noted by Asher (1993), these constructions could involve also facts.

-

(i)

-

(i)

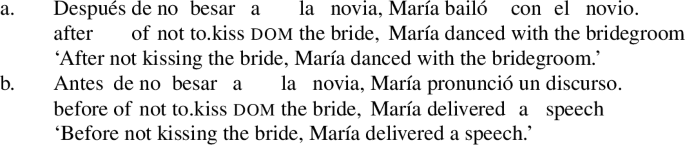

Notice that these adverbials exclude the sentential negation reading like durative modifiers do. They require an eventuality and the sentential negation interpretation does not satisfy this requirement, since it is denied that the eventuality took place.

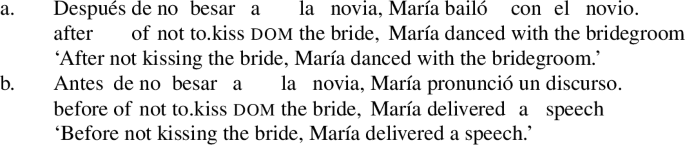

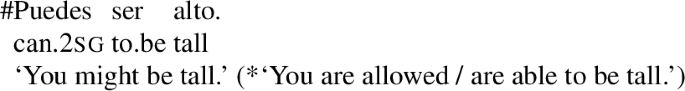

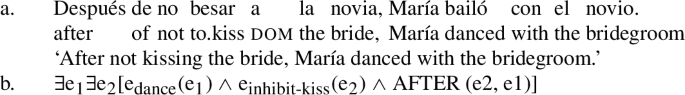

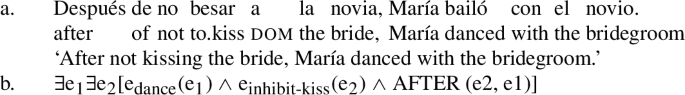

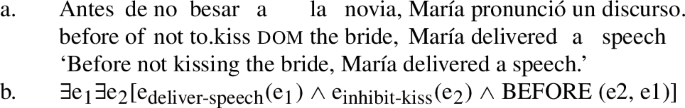

The fact that conjunctions with temporal meaning can combine with negative infinitives (Le Draoulec 1998) also argues for an eventuality denotation for the non-sentential reading. Facts cannot define temporal intervals. The grammaticality of (i), therefore, supports the claim that the negative reading denotes an eventuality. <Después de ‘after’ + infinitive> and <antes de ‘before’ + infinitive> structures have no interpretation beside a temporal one as they establish a temporal relation between the event of the embedded clause and the one in the main clause. Thus, (ia) describes a situation in which the eventuality of not kissing the bride takes place during a specific time period, which is followed by a time period during which María dances with the bridegroom. (ib) denotes that the period in which the eventuality of María not kissing the bride takes place is preceded by the time period in which María’s speech occurs.

-

(i)

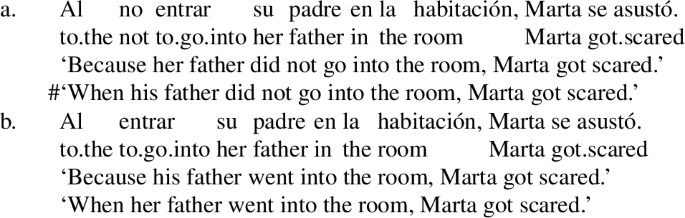

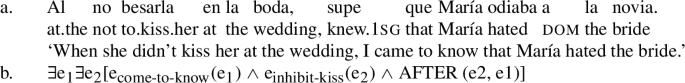

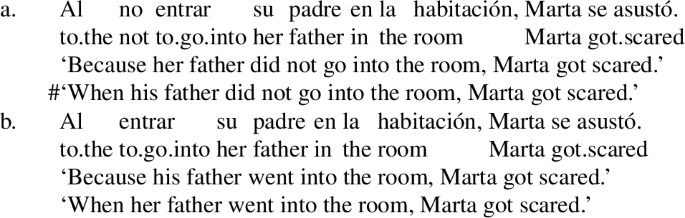

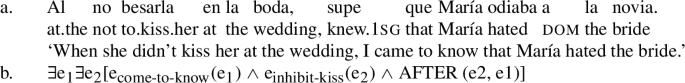

Rigau (1995, 1998), discussing temporal constructions in Spanish (and Catalan), claims that the infinitival construction <al + infinitive> only receives a causal reading when the infinitive is negated (see (iia)). If negation is not present, the temporal reading is possible (see (iib)).

-

(ii)

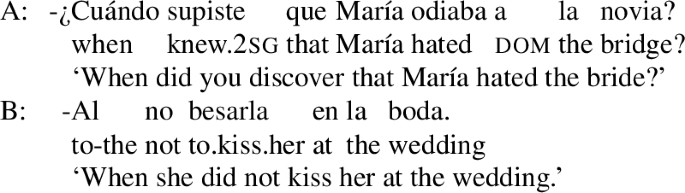

However, as predicted by a proposal where the relevant reading does not denote a fact, there are situations in which the infinitive preceded by negation can denote a particular time period, as shown by (iii).

-

(iii)

-

(i)

De Swart (1996) offers a similar argument for the existence of negative eventualities—specifically, in her opinion, of negative states: the possibility of relating an anaphoric pronoun to a negative clause (see (i)). However, as noted in fn. 8, Asher (1993) points out that anaphoric pronouns can also refer to facts (see (ib)) and, as a result, (ia) is not a strong argument in favour of negative eventualities (Przepiórkowski 1999).

-

(i)

.

-

a.

Su colega no asistió a la reunion. Eso provocó sorpresa.

‘His colleague did not attend the meeting. This caused surprise.’

-

b.

Su colega asistió a la reunion. Sin embargo, Luis no se lo cree.

‘His colleague attended the meeting. However, Luis does not believe it.’

-

a.

-

(i)

We do not take into account temporal properties such as the present tense interpretation (Csirmaz 2008; Marín and McNally 2011) and the possibility of moving the reference time of discourse forward (Kamp and Reyle 1993:547–548; de Swart and Molendijk 1999:3; Przepiórkowski 1999:241). In these contexts, the negated event reading does not seem to be excluded and it could be at play here.

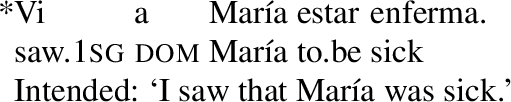

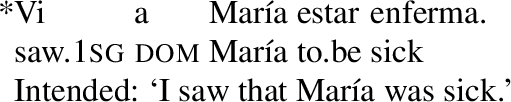

Of course, the very nature of the perception verb ver ‘see’ requires the embedded infinitive to denote an object that can be seen. Note, however, that the states used in our ungrammatical examples are easily perceived visually. An anonymous reviewer points out that Spanish seems to also allow stage level states in this construction; the reviewer documents the example Te he visto estar mal, lit. ‘I have seen you to be bad’ through Google. To us, this example is less than perfect as copulative verbs do not always produce states (see below for evaluative adjectives such as ser amable ‘to be nice’, which behave as activities, cf. Arche 2006). The type of complement that the verb takes influences the aspectual properties of the whole predicate. Importantly, mal ‘bad’ is an adverbial used to express manner. We propose that speakers who consider this Google-attested example as grammatical are plausibly taking the manner component of the adverb to define an event of maintaining oneself in a bad manner; however, none of the native speakers consulted (or the authors of this article) consider the example fully grammatical.

A similar argument is found for deontic modals. Note that the emerging reading in the example illustrated in (3b), repeated here in (ia), involves permission; examples denoting capacity can also be built (see (ib)).

-

(i)

With stative verbs, on the other hand, permission and capacity readings are excluded, plausibly, because the holder of a state lacks control over the state (Lakoff 1970, pace Pylkännen 2000).

-

(i)

Thus, modal verbs also provide an argument that the low negation giving rise to the reading in which the entity denoted by the subject does not initiate the event, does not force a stative interpretation.

-

(i)

As noted by a reviewer, until-phrases deserve a more detailed study. Under the analysis mentioned here, the grammaticality of (41b) is due to the durative nature of inhibited eventualities, which implies that until has the same denotation regardless of the polarity of the sentence (see Smith 1974 and Mittwoch 1977). However, Kartunnen (1974) argues against this type of account and proposes that two different untils should be differentiated, a durative one and a punctual one. The former appears in affirmative sentences whereas the latter is a negative polarity item that occurs in negative sentences. If we assume this account, the grammaticality of (41b) would not be an argument for the durative nature of negative eventualities. In fact, de Swart (1996) shows that both types of analysis give rise to the same truth conditions and the same implicatures. The possible differentiation between durative and punctual until must be evaluated on the basis of its possible negative polarity status, which may differ through languages. Because of the complexity of this issue, we will leave for future research the status of this item in Spanish and its interaction with negative eventualities.

Given this generalisation, the grammaticality of (2b) constitutes evidence in favour of the proposal, going back to at least Bolinger (1973), that weather verbs include a subject—possibly a spatio-temporal entity—whose internal properties trigger the meteorological event (as independently suggested by the grammaticality of sentences like It snowed without raining). Note that weather verbs cannot be causativised, which supports the view that they contain InitP.

As Cooper (1997:2) puts it: this makes a difference in terms of negation since on the situation theoretic approach it is possible to negate an infon and thus get a narrow scope negation corresponding to the claim “e is an event of Smith not hiring Jones” in addition to the wider scope negation which is available in both the Austinian and the Davidsonian approaches corresponding to the claim “e is not an event of Smith hiring Jones.”

The conditions to satisfy the inhibited event can be even weaker. Partee (2012) notes the example I actually saw Khrushchev not bang his shoe, which is intuitively true even in a situation where Khrushchev does not consider at any moment to bang his shoe on the table. The proposal that the causative relation between the initiator and the process is denied also explains cases like these, because it limits itself to saying that the particular participant did not start an event of banging his shoe.

Notice that Ramchand (2008) does not allow the option of the highest projection of a predicate being ResP, given that the distinction between Init and Res is configurational: Res is the interpretation that a stative head receives when it is embedded under Proc.

An anonymous reviewer correctly notes that there is some resemblance between our approach and the distinction between event types or kinds and event particulars or tokens advocated for in Gehrke and McNally (2011, 2015), Gehrke (2015) (see also Carlson 2003; Landman and Morzycki 2003; Mueller-Reichau 2013; Schwarz 2014; Grimm and McNally 2015). As in this account, event types are abstract objects that, through combination with the functional verbal structure, can become particular instantiations. This, therefore, raises the question of whether our account could be transformed into one using these two primitives rather than the descriptive properties of events and eventualities. We will not discuss this possibility here. In our account, such modifiers are allowed because negation merely builds the inhibited versions of the corresponding events, which can be located in space. Then, they are instantiated in a particular situation, which can be located in time. Given this empirical difference, it seems, to us, that the distinction between event kinds and event tokens, if appropriate, is, in itself, orthogonal to the type of data that we discuss in this article. See also Ramchand (2018:17–18) for some theoretical differences between the two approaches.

With respect to temporal clauses (cf. fn. 10), given that an eventuality whose existence is not denied is found in the inhibited eventuality reading, the time parameter of that eventuality can be ordered with respect to a second eventuality, just like the eventualities corresponding to positive descriptions. See (i), (ii) and (iii), where we adapt Vikner’s (2004) proposal about temporal clauses as one of the two arguments of a temporal operator introduced by the conjunction. We treat al + infinitive temporal structures as imposing a semantics equivalent to ‘before’ in their temporal reading.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

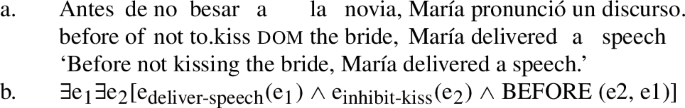

The formulas above clearly show that if negation operates over the existential closure of the event associated to the temporal clause, the denotation of the temporal operator is not satisfied, because one of the two events that it orders would be asserted not to exist.

-

(i)

Barwise (1981) famously argued that the complements of perception verbs denote a situation. This cannot be the case since perception verbs are sensitive to dynamicity—a property related to the event level.

-

(i)

-

(i)

References

Arche, María Jesús. 2006. Individuals in time: Tense, aspect and the individual/stage distinction. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Arkadiev, Peter. 2015. Negative events: Evidence from Lithuanian. In Donum semanticum: Opera linguistica et logica in honorem Barbarae Partee a discipulis amicisque Rossicis oblata, eds. Peter Arkadiev, Ivan Kapitonov, Yury Lander, Ekaterina Rakhilina, and Sergei Tatevosov, 7–20. Moscow: LRC Publishing.

Arkadiev, Peter. 2016. Long-distance genitive of negation in Lithuanian. In Argument realization in Baltic, eds. Axel Holvoet and Nicole Nau, 37–82. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Asher, Nicolas. 1993. Reference to abstract objects in discourse. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Bach, Edmond. 1986. The algebra of events. Linguistics and Philosophy 9: 5–16.

Barwise, Jon. 1981. Scenes and other situations. The Journal of Philosophy 78: 369–397.

Barwise, Jon. 1988. The situation in logic. Stanford: CSLI.

Barwise, Jon, and Robin Cooper. 1993. Extended Kamp Notation: A graphical notation for situation theory. In Situation theory and its applications, eds. Peter Aczel, David Israel, Yasuhiro Katagiri, and Stanley Peters, 29–53. Stanford: CSLI.

Barwise, Jon, and John Etchemendy. 1987. The liar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barwise, Jon, and John Perry. 1983. Situations and attitudes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bennett, Michael, and Barbara Partee. 1972. Towards the logic of tense and aspect in English. In Technical report (1972). Santa Monica: System Development Corporation. Published with a new appendix (1978) by Indiana Linguistics Club, Univ. of Indiana, Bloomington.

Bennis, Hans. 2000. Adjectives and argument structure. In Lexical specification and lexical insertion, eds. Peter Coopmans, Martin Everaert, and Jane Grimshaw, 27–69. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bertinetto, Pier Marco. 1986. Tempo, aspetto e azione nel verbo italiano. Firenze: Academia della Crusca.

Bolinger, Dwight. 1973. Ambient it is meaningful too. Journal of Linguistics 9: 261–270.

Carlson, Gregory. 1977. Reference to kinds in English. PhD diss., Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Carlson, Gregory. 2003. Weak indefinites. In From NP to DP, eds. Martine Coene and Yves D’hulst, 195–210. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Champollion, Lucas. 2015. The interaction of compositional semantics and event semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy 38: 31–66.

Cooper, Robin. 1996. The role of situations in generalized quantifiers. In Handbook of contemporary semantic theory, ed. Shalom Lappin, 65–86. Oxford: Blackwell.

Cooper, Robin. 1997. Austinian propositions, Davidsonian events and perception complements. In The Tbilisi symposium on language, logic and computation: Selected papers, eds. Jonathan Ginzburg, Zurab Khasidashvili, Jean-Jaques Levy, and Enric Vallduví, 19–34. Stanford: CSLI.

Cormack, Annabel, and Neil Smith. 2002. Modals and negation in English. In Modality and its interaction with the verbal system, eds. Sjef Barbiers, Frits Beukema, and Wim van der Wurff, 143–173. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Csirmaz, Anniko. 2008. Aspect, negation and quantifiers. In Event structure and the left periphery, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 225–253. Dordrecht: Springer.

Davidson, Donald. 1969. The individuation of events. In Essays in honor of Carl G. Hempel, ed. Nicholas Rescher, 216–234. Dordrecht: Reidel.

De Miguel, Elena. 1999. El aspecto léxico. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, eds. Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte, 2977–3060. Madrid: Espasa.

Doron, Edit. 1990. Situation semantics and free indirect discourse with examples from contemporary Hebrew fiction. Hebrew Linguistics 28: 21–29.

Dowty, David R. 1979. Word meaning and Montague grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Dretske, Fred. 1969. Seeing and knowing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eckhardt, Regine. 2012. ‘Hereby’ explained: An event-based account of performative utterances. Linguistics and Philosophy 35: 21–55.

Eide, Kristin Melum. 2006. Norwegian Modals. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Elbourne, Paul. 2005. Situations and individuals. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Fábregas, Antonio, and Raquel González Rodríguez. 2019. Perífrasis e inductores negativos: un análisis en términos de dominios. Onomázein. Revista de lingüística, filología y traducción 43, 95–113.

Fernald, Theodore. 1999. Evidential coercion: Using individual-level predicates in stage-level enviroments. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 29: 43–63.

Folli, Raffaella, and Heidi Harley. 2007. Causation, obligation and argument structure: The nature of little v. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 197–238.

García Fernández, et al.. 2006. Diccionario de perifrasis verbales. Madrid: Gredos.

Gawron, Jean Mark and Stanley Peters. 1990. Anaphora and quantification in situation semantics. Stanford: CSLI.

Gehrke, Berit. 2015. Adjectival participles, event kind modification and pseudo-incorporation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 33: 897–938.

Gehrke, Berit, and Louise McNally. 2011. Frequency adjectives and assertions about event types. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 19, eds. Cormany Satoshi Ito and David Lutz, 180–197.

Gehrke, Berit, and Louise McNally. 2015. Distributional modification: the case of frequency adjectives. Language 91: 837–870.

Geuder, Wilhelm. 2002. Oriented adverbs. PhD diss., Universität Tübingen.

Ginzburg, Jonathan. 2005. Situation Semantics: The ontological balance sheet. Research on language and Computation 3: 363–389.

Ginzburg, Jonathan, and Ivan Sag. 2000. Interrogative investigations. Stanford: CSLI.

Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1988. Perífrasis verbales: sintaxis, semántica y estilística. Madrid: Arco/libros.

González Rodríguez, Raquel. 2015. Negation of resultative and progressive periphrases. Borealis 4: 31–56.

Grimm, Scott, and Louise McNally. 2015. The -ing dynasty: Rebuilding the semantics of nominalizations. Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 25: 82–102.

Harley, Heidi. 2013. External arguments and the Mirror Principle: On the distinctness of Voice and v. Lingua 125: 35–57.

Henderson, Robert. 2016. Pluractional demonstrations. Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 26: 667–683.

Higginbotham, James. 1983. The logic of perceptual reports: an extensional alternative to situation semantics. Journal of Philosophy 80: 100–127.

Higginbotham, James. 1996. On events in linguistic semantics. Ms., Oxford University. Version of 25 June 1997.

Higginbotham, James. 2000. On events in linguistic semantics. In Speaking of events, eds. James Higginbotham, Fabio Pianesi, and Achille, 49–79. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hintikka, Jaakko. 1969. On the logic of perception. In Models for modalities, 151–183. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hoepelman, Jakob, and Christian Rohrer. 1980. On the mass-count distinction and the French imparfait and passé simple. In Time, tense, and quantifiers, ed. Christian Rohrer. 85–112. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Horn, Laurence. 1989. A natural history of negation. Stanford: CSLI.

Iatridou, Sabine, and Hedde Zeijlstra. 2013. Negation, polarity and deontic modals. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 529–568.

Jaque, Matías. 2014. La expression de la estatividad en español: niveles de representación y grados de dinamicidad. PhD diss., Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Kamp, Hans, and Uwe Reyle. 1993. From discourse to logic. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kartunnen, Lauri. 1974. Until. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 10, 284–297. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Kertz, Laura. 2006. Evaluative adjectives: An adjunct control analysis. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 25, eds. Donald Baumer, David Montero, and Michael Scanlon, 229–235. Cascadilla.

Klein, Wolfgang. 1994. Time in language. London: Routledge.

Koontz-Garboden, Andrew. 2009. Anticausativization. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 27: 77–139.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1989. An investigation of the lumps of thought. Linguistics and Philosophy 12: 607–653.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2002. Facts: Particulars or information units? Linguistics and Philosophy 25: 655–670.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2007. Situations in natural language semantics. In Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Stanford: The Metaphysics Research Lab. Available at https://plato.stanford.edu/. Accessed 16 October 2019.

Krifka, Manfred. 1989. Nominal reference, temporal constitution and quantification in event semantics. In Semantics and Contextual Expression, eds. Renate Bartsch, Johan van Benthem, and Peter van Emde Boas, 75–115. Dordrecht: Foris.

Laka, Itziar. 1990. Negation in syntax: on the nature of functional categories and projections. PhD diss., MIT.

Lakoff, George. 1966. Stative adjectives and verbs in English. Mathematical linguistics automatic translation; report to the national Science Foundation 17, Computational Laboratory, Harvard University.

Lakoff, George. 1970. Irregularities in syntax. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Landau, Idan. 2010. Saturated adjectives, reified properties. In Lexical semantic, syntax, and event structures, eds. Malka Rappaport Hovav, Edit Doron, and Ivy Sichel, 204–225. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Landman, Maredith, and Marcin Morzycki. 2003. Event-kinds and the representation of manner. In Western Conference on Linguistics (WECOL) 2002, ed. Nancy Mae Antrim, Grant Goodall, Martha Schulte-Nafeh, and Vida Samiian, 136–147. Fresno: California State University.

Le Draoulec, Anne. 1998. La négation dans less subordonnées temporelles. In Variations sur la référence verbale, eds. Andrée Borillo, Carl Vetters, and Marcel Vuillaume, 256–276. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Maienborn, Claudia. 2003. Die logische Form von Kopula-Sätzen. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Maienborn, Claudia. 2005. On the limits of the Davidsonian approach: The case of copula sentences. Theoretical Linguistics 31: 275–316.

Marín, Rafael. 2004. Entre ser y estar, Madrid: Arco/Libros.

Marín, Rafael, and Louise McNally. 2011. Inchoativity, change of state, and telicity: Evidence from Spanish reflexive psychological verbs. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 48: 35–70.

Mittwoch, Anita. 1977. Negative sentences with until. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 13, 410–417. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Mittwoch, Anita. 1990. On the distribution of bare infinitive complements in English. Journal of Linguistics 26: 103–131.

Mourelatos, Alexander P. 1978. Events, processes and states. Linguistics and Philosophy 2: 415–434.

Mueller-Reichau, Olav. 2013. On Russian factual imperfectives. In Formal Description of Slavic Languages (FDSL) 9, Göttingen 2011, eds. Uwe Junghanns, Dorothee Fehrmann Denisa Lenertová, and Hagen Pitsch, Vol. 28 of Linguistik International, 191–210. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Oshima, David Y. 2009. Between being wise and acting wise: A hidden conditional in some constructions with propensity adjectives. Journal of Linguistics 45: 363–393.

Partee, Barbara. 2012. I actually saw Khrushchev not bang his shoe. Language Log. Available at http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3995. Accessed 16 October 2019.

Picallo, M. Carme. 1990. Modal verbs in Catalan. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 8: 285–312.

Przepiórkowski, Adam. 1999. On negative eventualities, negative concord and negative yes/no questions. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 9, eds. Tanya Matthews and Devon Strolovitc. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Pylkännen, Liina. 2000. On stativity and causation. In Events as grammatical objects, eds. Carol Tenny and James Pustejovsky, 417–442. Stanford: CSLI.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2005. Two types of negation in Bengali. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. Veneeta Dayal and Anoop Mahajan, 39–66. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2008. First phase syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2018. Situations and syntactic structures. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Ramchand, Gillian, and Peter Svenonius. 2014. Deriving the functional hierarchy. Language Sciences 46: 152–174.

Rappaport-Hovav, Malka, and Beth Levin. 2000. Classifying single argument verbs. In Lexical specification and insertion, eds. Peter Coopmans, Martin Everaert, and Jane Grimshaw, 269–304. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Récanati, Francois. 1986/1987. Contextual dependence and definite descriptions. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 87: 57–73.

Rigau, Gemma. 1995. The properties of the temporal infinitive constructions in Catalan and Spanish. Probus 7: 279–301.

Rigau, Gemma. 1998. On temporal and causal infinitive constructions in Catalan dialects. Catalan Working Papers in Linguistics 6: 95–114.

Rothmayr, Antonia. 2009. The structure of stative verbs. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Schwarz, Florian. 2014. How weak and how definite are Weak Definites? In Weak Referentiality, eds. Ana Aguilar-Guevara, Bert Le Bruyn, and Joost Zwarts, 213–236. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Smith, Steven B. 1974. Meaning and negation. The Hague: Mouton.

Stockwell, Robert P., Paul Schachter, and Barbara H. Partee. 1973. The major syntactic structures of English. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston Inc.

Stowell, Tim. 1991. The alignment of arguments in adjective phrases. In Perspectives in phrase structure, ed. Suzan Rothstein, 105–135. New York: Academic Press.

de Swart, Henriëtte. 1993. Adverbs of quantification: A generalized quantifier approach. New York: Garland Press.

de Swart, Henriëtte. 1996. Meaning and use of not…until. Journal of Semantics 13: 221–263.

de Swart, Henriëtte, and Arie Molendijk. 1999. Negation and the temporal structure of narrative discourse. Journal of Semantics 16: 1–42.

Talmy, Leonard. 1988. Force dynamics in language and cognition. Cognitive science 12: 49–100.

Thomason, Richmond H. 1973. Semantics, pragmatics, conversation and presupposition. In Proceedings of the Texas conference on performatives, presuppositions and conversational implicatures, eds. John Murphy, Andy Rogers, and Robert Wall. Washington D.C.: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Verkuyl, Henk J. 1993. A theory of aspectuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vikner, Carl. 2004. Scandinavian when clauses. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 27: 133–167.

Weiser, Stéphanie. 2008. The negation of Action Sentences. Are there Negative Events? In ConSOLE 15, eds. Sylvia Blaho, Camila Constantinescu, and Erik Schoorlemmer, 357–364.

Wiltschko, Martina. 2014. The universal structure of categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wolff, Phillip. 2007. Representing causation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 136: 82–111.

Wolff, Phillip, and Jason Shepard. 2013. Causation, touch and the perception of force. Psychology of Learning and Motivation 58: 167–202.

Acknowledgements

The research underlying this article has been financed by grant Variación gramatical del español: microparámetros en las interficies sintaxis-semántica-discurso (FFI 2017-87140-C4-3-P). We are grateful to Luis García Fernández, Gillian Ramchand, Kjell Johan Sæbø, Cristina Sánchez, Henriette de Swart, Hedde Zeijlstra and three anonymous reviewers of Natural Language and Linguistic Theory for data, useful comments and suggestions. All disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fábregas, A., González Rodríguez, R. On inhibited eventualities. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 38, 729–773 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09461-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09461-y