Abstract

This paper shows that inverse marking and portmanteau agreement are in complementary distribution in Algonquin: inverse marking is possible only in contexts where portmanteau agreement is not. This correlation holds despite intralanguage variation in both phenomena. The paper proposes that the two phenomena pattern together because both are determined by the outcome of the Agree operation on Infl. When Infl enters a Multiple Agree relation with both arguments, the realization of portmanteau agreement morphology is possible. When Infl agrees only with the object, it duplicates the result of an earlier object agreement operation on Voice. The presence of identical features on Infl and Voice triggers an impoverishment operation that deletes the features of Voice, resulting in its spellout as an underspecified elsewhere form—which is the exponent that we know descriptively as the inverse marker. This analysis explains why inverse marking and portmanteau agreement never co-occur in Algonquin: the two phenomena are determined by alternative outcomes of the Agree operation on Infl. The analysis also enables a simple account of the intralanguage variation in the patterning of the two phenomena, which is shown to follow from variation in the specification of the probe on Infl.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

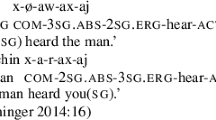

Interlinear glosses employ the Leipzig glossing conventions, with the following additions: 1pl = exclusive first-person plural, 21pl = inclusive first-person plural, 3 = proximate third person, 3′ = obviative third person, dir = direct, inv = inverse, t.s. = theme sign, X→Y = X acts on Y. Other abbreviations that occur in the paper are: PA = Proto-Algonquian, SUBJ = logical subject, OBJ = logical object, [Pers, Prox, Part, Addr] = [Person, Proximate, Participant, Addressee]. For compactness, feminine is used as a default in English translations of Algonquin 3sg forms, which show no masculine-feminine contrast.

Kitigan Zibi has also been known as River Desert or Maniwaki (as in Jones 1977).

The use of [Addressee] to distinguish 1st and 2nd persons follows Béjar and Rezac (2009), but either [Addressee] or [Speaker] would be equally sufficient for the purposes of my analysis. The representation of inclusive 1st-person plurals may involve both [Addressee] and [Speaker] (Harley and Ritter 2002).

Although I follow Béjar and Rezac’s approach to person features, I do not adopt their Cyclic Agree model of agreement. The Cyclic Agree analysis of Ojibwe theme signs in Béjar and Rezac (2009) is grounded in the premise that all theme signs are direct/inverse markers, but I argued in Sect. 3.1 that most theme signs are better understood as object agreement. Under this interpretation of the data, standard downward-probing Agree gives the simplest account.

The equidistance proposed in (13) is consistent with Richards’ (2001:102) suggestion that multiple specifiers created by A-movement are equidistant while those created by A-bar movement are not.

This definition of portmanteau agreement could be taken to apply not only to agreement suffixes like -agogw (Infl) but also to the inverse theme sign -igw (Voice), which is sensitive to the relative rank of the two arguments on the person hierarchy 1/2 > 3 > 3′ (Sect. 3.1). Because of their sensitivity to both arguments, inverse (and direct) theme signs have been characterized as portmanteaux by Trommer (2003) and Fry (2015). One important difference, however, is that the inverse theme sign expresses only a relation (“object outranks subject”) whereas a true portmanteau agreement marker such as -agogw indexes particular person and number features (1sg→2pl). In Sect. 5 the apparent portmanteau nature of the inverse theme sign will be attributed to an impoverishment operation that involves both Voice and Infl.

The 1pl suffix has two allomorphs, -inaːn (in (22)) and -imin (in (24)), which go back to Proto-Algonquian (PA) *-wenaːn and *-ehmenaːn respectively. PA *-wenaːn (> -inaːn) occurred in non-final position (i.e. when followed by a peripheral suffix) and *-ehmenaːn (> -imin) occurred in final position (i.e. when not followed by a peripheral suffix) (Goddard 2007). In Algonquin, the loss of final vowels has made the conditioning of the two allomorphs more opaque, as both can now be found in final position.

When an Algonquin clause contains two referential third persons, only one can be proximate; the other must be obviative (see e.g. Rhodes 1990). This restriction applies to referential third persons only. First, second, and impersonal third persons do not participate in or trigger obviation.

Similarly, Bruening (2005:22) suggests that in local forms in the Eastern Algonquian language Passamaquoddy, both arguments move to the specifier of InflP.

This generalization appears to hold in all Algonquian languages (Oxford 2017b), although space limitations prevent the presentation of supporting data here.

I assume that the agreement of Voice with the object does not prevent Infl from also agreeing with the object. That is, Chomsky’s (2000, 2001) Activity Condition does not constrain the outcome of the Agree operation in Algonquin. Baker (2008) has shown that this is the case for many languages; see Oxford (2017a) for discussion specific to Algonquian languages.

The formulation of the constraint as applying to “two adjacent heads” may in fact be too strong, as Neg can intervene between Voice and Infl without disrupting the inverse-marking pattern. Some notion of locality is required, however, as the constraint applies to Voice and Infl but does not apply to Voice and C: regardless of which argument C agrees with, C-agreement never affects the appearance of inverse marking. Alternatives to strict adjacency include “two heads within the same phase” (cf. Richards 2010) or “two adjacent phi-bearing heads,” with intervening heads that do not bear phi-features (such as Neg) being transparent (cf. the transparency of underspecified segments in phonological dissimilation, e.g. Steriade 1987). I leave the precise formulation of the constraint to future work.

I thank Bethany Lochbihler (p.c.) for expressing to me the insight that the inverse is “elsewhere-like.”

I thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing the Kadiwéu parallel to my attention.

Or, alternatively, if we assumed “tucking in” of the object in multiple-specifier configurations such as (45) (Richards 2001), we would predict the unmarked order to be uniformly Subject-Object.

Bruening (2001) suggests that the same effect may hold in Passamaquoddy as well: “the object of the Inverse should pattern with the subject of the Direct in word order” (65). However, in his textual data “there are simply not enough examples of Inverse clauses with overt NPs to draw any definitive conclusions” (68).

The insight that A-movement of inverse objects can derive the unmarked word order is from Bruening (2001:65). I differ from Bruening, however, on the triggering of this movement, which I attribute to an articulated probe on Infl° but Bruening (2005) attributes to an [EPP] feature that is optionally added to Voice in precisely those forms in which inverse marking appears: “If the feature is present, the clause ends up being inverse; if it is absent, direct” (20). The optional [EPP] approach misses the fact that the appearance of inverse marking is not, in fact, optional, but rather fully predictable from the person features of the arguments. For example, inverse marking is obligatory in an Independent 3→1 form and impossible in a 1→3 form. If the addition of the [EPP] feature is optional, what ensures that this option is always exercised in 3→1 forms and never exercised in 1→3 forms?

The abbreviations in the glosses are those of Bruening (2005), except his obv is replaced by 3′.

Direct forms are normally characterized as 3→3′, but the direct form in (49a) is actually 3′→3′, with both arguments obviative. However, the subject otayihshan ‘his dog’ is marked as obviative only because it is possessed by a third person. Rhodes (1990:102,111–12) shows that such instances of DP-internal “possessor obviation” often do not affect the external morphosyntax of the DP, which can behave as though it were proximate for the purposes of apposition, agreement, and inverse marking. This is the case in the 3′→3′ direct form in (49a), which has the same morphosyntax as a regular 3→3′ direct form.

References

Aissen, Judith. 1999. Markedness and subject choice in Optimality Theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 17: 673–711.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2005. Strong and weak person restrictions: A feature checking analysis. In Clitic and affix combinations: Theoretical perspectives, eds. Lorie Heggie and Francisco Ordóñez, 199–235. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Arregi, Karlos, and Andrew Nevins. 2007. Obliteration vs. impoverishment in the Basque g-/z- constraint. In Penn Linguistics Colloquium (PLC) 30, eds. Tatjana Scheffler, Joshua Tauberer, Aviad Eilam, and Laia Mayol, 1–14. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. Working Papers in Linguistics 10.1.

Arregi, Karlos, and Andrew Nevins. 2008. Agreement and clitic restrictions in Basque. In Agreement Restrictions, eds. Roberta D’Alessandro, Susann Fischer, and Gunnar Hrafn Hrafnbjargarson, 49–85. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Baker, Mark C. 2008. The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Béjar, Susana. 2003. Phi-syntax: A theory of agreement. PhD diss., University of Toronto.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2009. Cyclic Agree. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 35–73.

Bliss, Heather. 2013. The Blackfoot configurationality conspiracy. PhD diss., University of British Columbia.

Bliss, Heather, Elizabeth Ritter, and Martina Wiltschko. 2014. A comparative analysis of theme marking in Blackfoot and Nishnaabemwin. In Papers of the 42nd Algonquian conference, eds. J. Randolph Valentine and Monica Macaulay, 10–33. Albany: SUNY Press.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1946. Algonquian. In Linguistic structures of native America, ed. Harry Hoijer, 85–129. New York: Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1962. The Menomini language. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan D., and Phil Branigan. 2006. Eccentric agreement and multiple case-checking. In Ergativity: Emerging issues, eds. Alana Johns, Dian Massam, and Ndayiragije Juvénal, 47–77. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bonet, Eulalia. 1991. Morphology after syntax: Pronominal clitics in Romance. PhD diss., MIT.

Branigan, Phil, and Marguerite MacKenzie. 1999. Binding relations and the nature of pro in Innu-aimun. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 29, eds. Pius Tamanji, Masako Hirotani, and Nancy Hall, 475–485.

Branigan, Phil, Julie Brittain, and Carrie Dyck. 2005. Balancing syntax and prosody in the Algonquian verb complex. In Papers of the 36th Algonquian conference, ed. H. C. Wolfart, 75–93. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

Brittain, Julie. 1999. A reanalysis of transitive animate theme signs as object agreement: Evidence from Western Naskapi. In Papers of the 30th Algonquian conference, ed. David H. Pentland, 34–46. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

Brittain, Julie. 2001a. The morphosyntax of the Algonquian conjunct verb: A Minimalist approach. New York: Garland.

Brittain, Julie. 2001b. Obviation and coreference relations in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi. Linguistica Atlantica 23: 69–91.

Brittain, Julie. 2003. A Distributed Morphology account of the syntax of the Algonquian verb. In 2003 annual conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, eds. Stanca Somesfalean and Sophie Burelle, 25–39.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2001. Syntax at the edge: Cross-clausal phenomena and the syntax of Passamaquoddy. PhD diss., MIT.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2005. The Algonquian inverse is syntactic: Binding in Passamaquoddy. Ms., University of Delaware.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2008. Quantification in Passamaquoddy. In Quantification: A cross-linguistic perspective, ed. Lisa Matthewson, 67–103. Bingley: Emerald.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2009. Algonquian languages have A-movement and A-agreement. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 427–445.

Campana, Mark. 1996. The conjunct order in Algonquian. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 41: 201–234.

Campbell, Amy M. 2012. The morphosyntax of discontinuous exponence. PhD diss., Berkeley.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on Minimalism in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cook, Clare. 2014. The clause-typing system of Plains Cree: Indexicality, anaphoricity, and contrast. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dahlstrom, Amy. 1989. Morphological change in Plains Cree verb inflection. Folia Linguistica Historica 22: 59–72.

Dahlstrom, Amy. 1995. Topic, focus and other word order problems in Algonquian. The 1994 Belcourt Lecture. Winnipeg: Voices of Rupert’s Land.

Fry, Brandon. 2015. The derivation of theme-signs in Algonquin Ojibwe: A multiple agree approach. Talk presented at the 2015 CLA Annual Conference, University of Ottawa.

Georgi, Doreen. 2013a. Deriving the distribution of person portmanteaux by relativized probing. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 42, eds. Stefan Keine and Shayne Sloggett, 155–168.

Georgi, Doreen. 2013b. A relativized probing approach to person encoding in local scenarios. Linguistic Variation 12: 153–210.

Goddard, Ives. 1974. Remarks on the Algonquian Independent Indicative. International Journal of American Linguistics 40: 317–327.

Goddard, Ives. 1979. Delaware verbal morphology: A descriptive and comparative study. New York: Garland.

Goddard, Ives. 2000. The historical origins of Cheyenne inflections. In Papers of the 31st Algonquian conference, ed. John D. Nichols, 77–129. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

Goddard, Ives. 2007. Reconstruction and history of the independent indicative. In Papers of the 38th Algonquian conference, ed. H. C. Wolfart, 207–271. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

Goddard, Ives. 2015. Arapaho historical morphology. Anthropological Linguistics 57: 345–411.

Halle, Morris. 1997. Distributed morphology: Impoverishment and fission. In Papers at the interface, eds. Benjamin Bruening, Yoonjung Kang, and Martha McGinnis, 425–449. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from Building 20, eds. Ken Hale and Samuel J. Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harbour, Daniel. 2008. Discontinuous agreement and the syntax-morphology interface. In Phi-theory: Phi-features across modules and interfaces, eds. Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Béjar, 185–230. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78: 482–526.

Heath, Jeffrey. 1991. Pragmatic disguise in pronominal-affix paradigms. In Paradigms: The economy of inflection, ed. Frans Plank, 75–89. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Heath, Jeffrey. 1998. Pragmatic skewing in 1 ↔ 2 pronominal combinations in native American languages. International Journal of American Linguistics 64: 83–104.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2001. Multiple Agree and the defective intervention constraint in Japanese. In HUMIT 2000, eds. Ora Matushansky et al., 67–80. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 40.

Hirose, Tomio. 2003. Origins of predicates: Evidence from Plains Cree. New York: Routledge.

Hockett, Charles F. 1966. What Algonquian is really like. International Journal of American Linguistics 32: 59–73.

Hockett, Charles F. 1992. Direction in the Algonquian verb: A correction. Anthropological Linguistics 34: 311–315.

Hornstein, Norbert. 2009. A theory of syntax: Minimal operations and Universal Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jones, David. 1977. A basic Algonquin grammar: For teachers of the language at Maniwaki, Quebec, Maniwaki: River Desert Band Council.

Junker, Marie-Odile. 2004. Focus, obviation, and word order in East Cree. Lingua 114: 345–365.

van Koppen, Marjo. 2005. One probe—two goals: Aspects of agreement in Dutch dialects. PhD diss., Leiden University.

van Koppen, Marjo. 2006. One probe, multiple goals: The case of first conjunct agreement. In Leiden Papers in Linguistics 3.2, eds. Marjo van Koppen et al., 25–52.

van Koppen, Marjo. 2008. Agreement with coordinated subjects. A comparative perspective. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 7: 121–161.

Kramer, Ruth. 2014. Clitic doubling or object agreement: The view from Amharic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32: 593–634.

Lochbihler, Bethany. 2012. Aspects of argument licensing. PhD diss., McGill University.

Lochbihler, Bethany, and Eric Mathieu. 2016. Clause typing and feature inheritance of discourse features. Syntax 19: 354–391.

Macaulay, Monica. 2009. On prominence hierarchies: Evidence from Algonquian. Linguistic Typology 13: 357–389.

Mathieu, Eric. 2007. Petite syntaxe des finales concrètes en ojibwe. In Papers of the 38th Algonquian conference, ed. H. C. Wolfart, 295–321. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

McGinnis, Martha. 1995. Word-internal syntax: Evidence from Ojibwa. In 1995 annual conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, ed. Paivi Koskinen, 337–347.

McGinnis, Martha. 1999. Is there syntactic inversion in Ojibwa? In Papers from the workshop on structure and constituency in native American languages, eds. Leora Bar-el, Rose-Marie Déchaine, and Charlotte Reinholtz, 101–118. MIT Occasional Papers in Linguistics 17.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 273–313.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 939–971.

Nichols, John D. 1980. Ojibwe morphology. PhD diss., Harvard.

Oxford, Will. 2014. Microparameters of agreement: A diachronic perspective on Algonquian verb inflection. PhD diss., University of Toronto.

Oxford, Will. 2017a. The Activity Condition as a microparameter. Linguistic Inquiry 48: 711–722.

Oxford, Will. 2017b. Inverse marking as impoverishment. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 34, eds. Aaron Kaplan et al., 413–422.

Pentland, David H. 1999. The morphology of the Algonquian independent order. In Papers of the 30th Algonquian Conference, ed. David H. Pentland, 222–266. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

Perlmutter, David M. 1971. Deep and surface structure constraints in syntax. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Perlmutter, David M., and Richard A. Rhodes. 1988. Thematic-syntactic alignments in Ojibwa: Evidence for subject-object reversal. Paper presented at the 63rd annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, New Orleans.

Preminger, Omer. 2009. Breaking agreements: Distinguishing agreement and clitic doubling by their failures. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 619–666.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1981. A second COMP position. In Theory of markedness in generative grammar: Proceedings of the 1979 GLOW conference, eds. Adriana Belletti, Luciana Brandi, and Luigi Rizzi, 517–551. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore.

Rhodes, Richard A. 1976. The morphosyntax of the Central Ojibwa verb. PhD diss., University of Michigan.

Rhodes, Richard A. 1990. Obviation, inversion, and topic rank in Ojibwa. In Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 16: Special session on general topics in American Indian linguistics, ed. David Costa, 101–115.

Rhodes, Richard A. 1994. Agency, inversion, and thematic alignment in Ojibwe. In Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 20, ed. Susanne Gahl, Andy Dolbey, and Christopher Johnson, 431–446.

Rhodes, Richard A. 2006. Ojibwe language shift: 1600–present. Paper presented at Historical Linguistics and Hunter-Gatherer Populations in Global Perspective, MPI-EVA Leipzig.

Rhodes, Richard A., and Evelyn Todd. 1981. Subarctic Algonquian languages. In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 6: Subarctic, ed. June Helm, 52–66. Washington: Smithsonian.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. Movement in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richards, Norvin. 2004. The syntax of the conjunct and independent orders in Wampanoag. International Journal of American Linguistics 70: 327–368.

Richards, Norvin. 2010. Uttering trees. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2014. The composition of INFL: An exploration of tense, tenseless languages, and tenseless constructions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32: 1331–1386.

Russell, Kevin, and Charlotte Reinholtz. 1995. Hierarchical structure in a nonconfigurational language: Asymmetries in Swampy Cree. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 14, eds. Jose Camacho, Lina Choueiri, and Maki Watanabe, 431–445.

Sandalo, Filomena. 2016. The relational morpheme of Brazilian languages as an impoverished agreement marker. In Workshop on Structure and Constituency in the Languages of the Americas (WSCLA) 20 (UBCWPL 43), eds. Emily Sadlier-Brown, Erin Guntly, and Natalie Weber, 82–88.

Statistics Canada. 2013. Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, Indian band area, Quebec (Code 630073). National Household Survey (NHS) Aboriginal Population Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Catalogue no. 99-011-X2011007. Available at http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/aprof/index.cfm?Lang=E. Accessed December 20, 2016.

Steriade, Donca. 1987. Redundant values. In Chicago Linguistic Society 23, Part 2, eds. Anna Bosch, Barbara Need, and Eric Schiller, 339–362.

Tollan, Rebecca, and Will Oxford. 2018. Voice-less unergatives: Evidence from Algonquian. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 35, eds. William G. Bennett, Lindsay Hracs, and Dennis Ryan Storoshenko, 399–408.

Tomlin, Russell, and Richard A. Rhodes. 1979. An introduction to information distribution in Ojibwa. Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 15: 307–320.

Trommer, Jochen. 2003. Distributed optimality. PhD diss., Universität Potsdam.

Trommer, Jochen. 2007. On portmanteau agreement. Talk presented at the Harvard-Leipzig Workshop on Morphology and Argument Encoding, Harvard.

Trommer, Jochen. 2010. The typology of portmanteau agreement. Talk presented at the DGfS-CNRS Summer School on Linguistic Typology, Leipzig.

Ura, Hiroyuki. 1996. Multiple feature-checking: A theory of grammatical function splitting. PhD diss., MIT.

Valentine, J. Randolph. 1994. Ojibwe dialect relationships. PhD diss., University of Texas, Austin.

Valentine, J. Randolph. 2001. Nishnaabemwin reference grammar. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Wolfart, H. C. 1973. Plains Cree: A grammatical study. Vol. 63 of Transactions of the American philosophical society, Part 5. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Wolvengrey, Arok. 2011. Semantic and pragmatic functions in Plains Cree syntax. PhD diss., University of Amsterdam.

Woolford, Ellen. 2008. Active-stative agreement in Lakota: Person and number alignment and portmanteau formation. Ms., University of Massachusetts.

Woolford, Ellen. 2010. Active-stative agreement in Choctaw and Lakota. Revista Virtual de Estudos da Linguagem 8: 6–46.

Wunderlich, Dieter. 2005. The challenge by inverse morphology. Lingue e Linguaggio 4: 195–214.

Zúñiga, Fernando. 2006. Deixis and alignment: Inverse systems in Indigenous languages of the Americas. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Zúñiga, Fernando. 2008. How many hierarchies, really? Evidence from several Algonquian languages. In Scales, eds. Marc Richards and Andrej L. Malchukov. Vol. 86 of Linguistische Arbeits Berichte, 277–294. Leipzig: Universität.

Acknowledgements

The material in this paper has benefited from the helpful comments of Jonathan Bobaljik, Phil Branigan, Brandon Fry, Michael Hamilton, Bethany Lochbihler, and four anonymous reviewers, as well as audiences at WCCFL 32 (USC), WSCLA 19 (Memorial), the 47th Algonquian Conference (Manitoba), WCCFL 34 (Utah), NELS 47 (UMass Amherst), and the University of Ottawa. The research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Insight Development Grant 430-2016-00680).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Algonquin agreement paradigms

Appendix: Algonquin agreement paradigms

Tables 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 display the agreement paradigms for Kitigan Zibi Algonquin AI (Animate Intransitive) and TA (Transitive Animate) verbs as provided in Jones (1977). The orthography follows that of Jones, with two exceptions: the phoneme /dƷ/ is written as <j> instead of <dj> (cf. Valentine 2001) and long vowels are marked by a colon instead of an acute accent.

The paradigms show the underlying morphemic forms. Surface forms are derived by applying the following rules: (1) /w/ deletes word-finally; (2) /i/ deletes word-finally; (3) /i/ deletes after a vowel; (4) /a/ deletes after a vowel; (5) /w-i/ coalesces to /o/; (6) /-igw-waː/ becomes /-igowaː/; (7) /-igw-j/ becomes /-igoj/; (8) /-igw-an/ becomes /-igoːn/; (9) /-ih-g/ becomes /-ik/.

The following abbreviations are used in the table headers: Pfx = person prefix (Infl); Agr = agreement; T.S. = theme sign (Voice); Centr = central agreement (Infl); Periph = peripheral agreement (C). All instances of inverse marking and portmanteau agreement (or multiple Infl-agreement) are shown in bold.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oxford, W. Inverse marking and Multiple Agree in Algonquin. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 955–996 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9428-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9428-x