Abstract

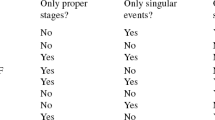

This paper looks at two different aspect splits in Neo-Aramaic languages that are unusual in that they do not involve any ergativity. Instead, these splits are characterized by agreement reversal, a pattern in which the function of agreement markers switches between aspects, though the alignment of agreement remains consistently nominative-accusative. Some Neo-Aramaic languages have complete agreement reversal, affecting both subject and object agreement (Khan 2002, 2008; Coghill 2003). In addition to this, we describe a different system, found in Senaya, which we call partial agreement reversal. In Senaya, the reversal only affects the marker of the perfective subject, which marks objects in the imperfective. We show that a unifying property of the systems that we discuss is that there is additional agreement potential in the imperfective. We develop an account in which these splits arise because of an aspectual predicate in the imperfective that introduces an additional φ-probe. This proposal provides support for the view that aspect splits are the result of an additional predicate in nonperfective aspects (Laka 2006; Coon 2010; Coon and Preminger 2012), because it allows for the apparently disparate phenomena of split ergativity and agreement reversal to be given a unified treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We are focusing here on the complete agreement reversal languages that exhibit an asymmetry between the perfective and the imperfective, in the form of a Person Case Constraint (PCC) effect. There are, however, a number of other types of systems that we will not discuss (see Doron and Khan 2012). Most notably, there are varieties with complete agreement reversal that do not exhibit a PCC effect in the perfective. For these, we think a morphological analysis of the aspect split is more appropriate, as argued in detail by Baerman (2007).

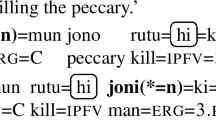

We make use of the following abbreviations: 1, 2, 3 = 1st, 2nd, 3rd person, I = noun class 1, III = noun class 3, abs = absolutive, aux = auxiliary, cl = clitic, conj = conjunction, erg = ergative, expl = expletive, f = female, fut = future, gen = genitive, impf = imperfective, indic = indicative, inf = infinitive, itv = intransitive verb suffix, L = L-suffix, m = male, nml = nominal, nmlz = nominalization, part = participle, pass = passive, perf = perfective, pl = plural, pres = present, S = S-suffix, s/sg = singular, sc = small clause, tv = transitive verb suffix. Senaya data come from original fieldwork on the language by Laura McPherson, Kevin Ryan, and the first author.

This asymmetry is the reason for our choice of examples above (intransitive perfective in (-1), transitive imperfective in (0)): the perfective verb base simply cannot appear with a definite object, as there is only one agreement slot, always occupied by subject agreement; this is discussed at length in Sect. 3.1.

These agreement markers are also sometimes referred to as the A-set suffixes (e.g., Hoberman 1989).

That the auxiliary is enclitic is evidenced by the fact that, in interrogative clauses, the auxiliary may behave as a second position element, encliticizing to fronted wh-words, e.g., (i):

-

(i)

The auxiliary also serves as a copula, encliticizing to predicate adjectives and nominals (Khan 2002:332).

-

(i)

In Senaya, the language that exhibits partial agreement reversal, there is actually very little evidence as to the status of L-suffixes as true agreement or as a clitic series. The L-suffixes are not phonological clitics in Senaya—adding an L-suffix to a verb triggers stress shift whereas adding the enclitic auxiliary does not—but their status as syntactic clitics is unknown. For the purposes of this paper, we will consider L-suffixes to be clitics in order to unify Senaya with the other Neo-Aramaic languages, but nothing in our analysis hinges on this.

The Senaya data in this paper comes from original fieldwork by Laura McPherson and Kevin Ryan (with recent participation by Laura Kalin), which has graciously been shared with us.

This way of representing the agreement alignment was originally conceived by Kevin Ryan.

The transitive perfective thus construed looks like an antipassive (since the object must be indefinite and cannot trigger agreement), while the transitive imperfective is the regular transitive configuration. However, this cannot be so, since the agreement configuration changes from the imperfective to the perfective in intransitives as well as transitives, but intransitives should not be able to be antipassivized.

There are two pieces of evidence for a high position for tm- in Senaya. First, tm- is in complementary distribution with the perfect prefix gii-, suggesting they compete for the same syntactic position. Perfect aspect has been argued to be generated above AspP, head of a PerfP projection (e.g., Iatridou et al. 2001). Second, it has been reported that in many Neo-Aramaic languages, the verb and object can be coordinated with other verb-object pairs to the exclusion of tm-, with tm- scoping over all elements in the coordination (Coghill 1999:41); when the perfective base is used in a series of coordinated verbs, on the other hand, all the verbs must appear in the perfective form in order to express perfective aspect.

The reason we put aside the tm- perfective for the purposes of this paper is as follows. The strategy for expressing perfective aspect seen in (15) (tm-prefixed on the imperfective verb base) can only be used when object agreement is required, i.e., for a perfective transitive with a definite (agreeing) object. We therefore do not consider this strategy to be the canonical way of expressing perfective aspect more generally—it would be difficult if not impossible to explain why the perfective strategy in (15) cannot be used for an intransitive perfective (or a transitive perfective with an indefinite object), given that the imperfective verb base (used as the basis of the construction in (15)) is perfectly capable of hosting just a single agreement morpheme, as in (-2a–c). If the perfective verb base, on the other hand, is taken to be the canonical way of expressing perfective aspect, then it is easy to see why (15) would surface as a secondary perfective strategy in Senaya: definite objects must be marked on the verb, and the imperfective verb base can host object agreement while the perfective verb base cannot. This line of reasoning extends to the languages discussed in Sect. 4, since they, too, have restrictions on object agreement in the perfective (though the restrictions are different from those in Senaya).

One might wonder whether L-suffixes might be the result of agreement with v. This would work in the perfective, so long as we give v the ability to probe upwards if it fails to find a goal when probing downwards, such that v can agree both with unaccusative subjects (complement of V) and with transitive/unergative subjects (Spec-vP), along the lines of Béjar and Rezac’s (2009) Cyclic Agree. However, such an approach would crucially fail in imperfective intransitives; see fn. 16.

Indefinite objects may even be separated from the verb by adverbial material. We propose that this is because the verb does undergo movement in Neo-Aramaic (as we also claim in Sect. 4.3.2).

Other recent research has also located an argument licenser on a head between T and v. First, Deal (2011) argues that subject agreement in Nez Perce is located on Asp, and further that “the choice of aspect/mood determines the form of subject number agreement” (11). Second, Halpert (2012a) proposes that in Zulu, a licensing head L is situated directly above vP and structurally licenses the highest nominal in vP.

An alternative to this would be to allow the subject to move around the probe, to Spec-TP, before T probes the object, as has been suggested for some ergative languages in which T assigns absolutive (Anand and Nevins 2006; Legate 2008; see also Holmberg and Hróarsdóttir 2003). We would then posit an EPP feature on T, which is activated before the person probe and serves to attract the subject so it no longer acts as an intervener.

Fn. 12 mentioned the logical possibility that v is the locus of L-suffixes in Senaya. As noted, in order to make this work in the perfective, we needed to add the stipulation that v has the ability to probe upwards if it fails to find a goal when probing downwards. However, in the imperfective, this proposal would fail outright. In particular, having a v that is endowed with Cyclic Agree properties (Béjar and Rezac 2009), and whose φ-probe spells out as an L-suffix, would predict intransitive subjects to be marked with an L-suffix in the imperfective, since v is a lower head than Asp. This is false empirically—intransitive subjects in the imperfective are marked with an S-suffix. We therefore reject this hypothesis.

It falls out naturally here that a clitic is not generated when the φ-probe on T fails to agree, resulting in the absence of an L-suffix in imperfective intransitives.

As noted in fn. 2, we only take into consideration complete agreement reversal languages which have a PCC effect in the perfective. For non-PCC varieties, we refer the reader to Baerman (2007), who argues for a morphological analysis of such agreement reversal.

It is not the case that all Neo-Aramaic languages with aspect-based agreement splits lack ergativity in the perfective. See Doron and Khan (2012) for a discussion of a broader range of Neo-Aramaic languages than we include here.

In order to express a 1st or 2nd person object with the perfective, these languages make use of two strategies. The object can be embedded under a preposition, in which case all persons are acceptable, or the perfective is expressed periphrastically, by putting a perfective prefix on the imperfective base (and agreement appears just as in the imperfective). See the discussion at the end of Sect. 3.1 and in fn. 11 on this phenomenon in Senaya.

Note that the syntactic signature of the PCC means that a morphological analysis of agreement reversal, as suggested by Baerman (2007) for the Neo-Aramaic language Amadiya, is not appropriate for Barwar or the other complete agreement reversal languages. For detailed argumentation that the PCC is syntactic, see Rezac (2011).

Béjar and Rezac ignore gender for the sake of simplicity, as number and gender generally pattern together. We will do the same here.

It has to be T that is active and not v, because otherwise this alignment would not map straightforwardly onto a PCC configuration. Specifically, if the φ-probe were on v, then we would have to make an additional stipulation about the directionality of probing (upwards then downwards) in order to account for the fact that the PCC affects objects and not subjects. In addition, while the perfective could be accounted for with this stipulation, it does not allow imperfective Asp to interfere in the desired way in the imperfective, as is needed to derive agreement reversal; see Sect. 4.2.

This spell-out rule applies only to φ-probes which are adjoined to the verb because there are some functional heads which have their own agreement paradigm, specifically the enclitic auxiliary used in copular constructions and a variety of other environments. See Sects. 4.3.1 and 4.3.2 for more detail.

Our thanks to an anonymous reviewer for discussion of this point.

An alternative approach would be to say that all definite objects move to Spec-vP (Diesing 1992), thus putting all such objects within range of T.

We then take the 3rd person forms of the S-suffixes to encode the absence of person, so that they spell out only number and gender agreement in these cases.

We might wonder whether we also expect to find Neo-Aramaic languages in which we see variation in the properties of Asp (i.e., whether it or its person/number probe is a clitic-doubler), since we are claiming that these are just lexical differences. We are not aware of any such dialect, but this is perhaps not surprising. Neo-Aramaic varieties all obey the verbal template S-suffix–Past tense–L-suffix. Because the S-suffix then reliably appears inside past tense morphology, it is unlikely to be reanalyzed as a clitic. The L-suffix, on the other hand, is always on the outside edge of the verb and so we might expect this position to be the source of variation, given that this makes the L-suffix compatible with a variety of analyses (e.g., as agreement, as a clitic, as a separate head).

Although we represent Asp as an undifferentiated probe here, it is also assumed to consist of a separate person and number probe. Since neither is a clitic-doubler, these probes will just always agree with the same argument.

In others, like Qaraqosh, the perfect and progressive make use of a nominalized participle or infinitive which inflects for object agreement with the same agreement that is found on nouns (Khan 2002). These then appear to involve a different structure. In Senaya, the perfect results simply from prefixing the perfective base with gii-, and there are otherwise no morphological changes; similarly, the progressive results from adding an auxiliary directly onto the imperfective base.

Note that perfect aspect and perfective aspect are formally distinct: whereas perfective aspect views an event as a whole, perfect aspect relates two times, “on the one hand the time of the state resulting from a prior situation, and on the other the time of that prior situation” (Comrie 1976:52).

In addition, the participle associated with the perfect inflects for the number and gender of the subject. We will not be too concerned here with the question of where this participial agreement is located. Presumably, perfect Asp is somehow associated with a bit of additional structure, like a PartP, which carries a number probe with it.

Equivalently, as per fn. 11, the φ-probe introduced by perfect Asp may appear on a Perf head directly above Asp. For simplicity, in this section we assume that perfect aspect appears on the Asp head directly.

The idea here is that, in all split-ergative Neo-Aramaic languages, perfective v assigns ergative case, to its specifier if it has one and to an internal argument otherwise. This mechanism seems problematic to us for a number of reasons. The idea that a case assigner can alternate between assigning case to its specifier and case to a DP in its c-command domain does not seem to be supported on independent grounds. Though Doron and Khan intend to treat ergative case as structural in these languages, this also seems to conflate inherent case and structural case, as the mechanism assigning case to a specifier is typically reserved for inherent case. Finally, it is not obvious how this mechanism can be prevented from over-generating. It remains unclear, for example, why v does not assign structural case to objects in transitives.

As Coon discusses, an implicational relationship seems to hold between the progressive and the imperfective, such that the progressive is always nominative-accusative if the imperfective is. See Coon (2010:169–170) for discussion of this and how to derive it.

This seems to be true of prepositions generally, in fact. Note that prepositions such as around, outside, and with do not truly convey a superset relation (Coon 2010:174–175).

If person always probes before number, then the converse situation, in which number is the clitic-doubler, should not have any clear effect on licensing (as both person and number will still target the same argument).

Assuming Burzio’s Generalization, such a system would also run into licensing problems with unaccusatives and passives, so that there would always be at least one argument that cannot be licensed.

References

Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. economy. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 21: 435–483.

Aldridge, Edith. 2008. Generative approaches to ergativity. Language and Linguistics Compass: Syntax and Morphology 2.5: 966–995.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2005. Strong and weak person restrictions: A feature checking analysis. In Clitic and affix combinations: Theoretical perspectives, eds. Lorie Heggie and Francisco Ordonez. Vol. 74 of Linguistics today, 199–235. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Anand, Pranav, and Andrew Nevins. 2006. The locus of ergative Case assignment: Evidence from scope. In Ergativity: Emerging issues, eds. Alana Johns, Diane Massam, and Juvénal Ndayiragije, 3–25. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Arregi, Karlos, and Andrew Nevins. 2012. Morphotactics: Basque auxiliaries and the structure of spellout. Dordrecht: Springer.

Baerman, Matthew. 2007. Morphological reversals. Journal of Linguistics 43: 33–61.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2003. Person licensing and the derivation of PCC effects. In Romance linguistics: Theory and acquisition, eds. Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux and Yves Roberge, 49–62. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2009. Cyclic agree. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 35–73.

Benmamoun, Elabbas. 2000. The feature structure of functional categories: a comparative study of Arabic dialects. London: Oxford University Press.

Bjorkman, Bronwyn. 2011. BE-ing default: The morphosyntax of auxiliaries. PhD diss., MIT.

Bonet, Eulàlia. 1991. Morphology after syntax: Pronominal clitics in Romance languages. PhD diss., MIT.

Bybee, Joan, and Östen Dahl. 1989. The creation of tense and aspect systems in the languages of the world. Studies in Language 13: 51–103.

Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: the framework. In Step by step: essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Coghill, Eleanor. 1999. The verbal system of North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. PhD diss., University of Cambridge, England.

Coghill, Eleanor. 2003. The Neo-Aramaic dialect of Alqosh. PhD diss., University of Cambridge.

Coghill, Eleanor. 2010. Ditransitive constructions in the Neo-Aramaic dialect of Telkepe. In Studies in ditransitive constructions: a comparative handbook, eds. Andrej Malchukov, Martin Haspelmath, and Bernard Comrie, 221–242. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect: An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coon, Jessica. 2010. Complementation in Chol (Mayan): A theory of split ergativity. PhD diss., MIT.

Coon, Jessica. 2013. TAM split ergativity. Language and Linguistics Compass 7.3: 171–200.

Coon, Jessica, and Omer Preminger. 2011. Towards a unified account of person splits. In Proceedings of the 29th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 29. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Coon, Jessica, and Omer Preminger. 2012. Taking ‘ergativity’ out of split ergativity: A structural account of aspect and person splits. lingBuzz/001556.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2011. Breaking down the ergative case. Presented at the Case by Case Workshop, École Normale Supérieure, Paris.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 2000. The primitives of temporal relations. In Step by step, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 157–186. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 2007. The syntax of time arguments. Lingua 117: 330–366.

Diesing, Molly. 1992. Indefinites. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1994. Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doron, Edit, and Geoffrey Khan. 2012. The typology of morphological ergativity in Neo-Aramaic. Lingua 122: 225–240.

Forker, Diana. 2010. The biabsolutive construction in Tsez. Paper presented at the Conference on Languages of the Caucasus at the University of Chicago.

Halpert, Claire. 2012a. Argument licensing and agreement in Zulu. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Halpert, Claire. 2012b. Structural case and nominal licensing in Zulu. Presented at GLOW 35, University of Potsdam.

Hoberman, Robert. 1988. The history of the Modern Aramaic pronouns and pronominal suffixes. Journal of the American Oriental Society 108: 557–575.

Hoberman, Robert. 1989. The syntax and semantics of verb morphology in Modern Aramaic: A Jewish dialect of Iraqi Kurdistan. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

Holmberg, Anders, and Thorbjörg Hróarsdóttir. 2003. Agreement and movement in Icelandic raising constructions. Lingua 113: 997–1019.

Iatridou, Sabine, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Roumyana Izvorski. 2001. Observations about the form and meaning of the Perfect. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 189–238. Amsterdam: MIT Press.

Kalin, Laura. 2014. Aspect and argument licensing in Neo-Aramaic. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Khan, Geoffrey. 2002. The Neo-Aramaic dialect of Qaraqosh. Leiden: Brill.

Khan, Geoffrey. 2008. The Neo-Aramaic dialect of Barwar: Grammar, Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill.

Krotkoff, Georg. 1982. A Neo-Aramaic dialect of Kurdistan: Texts, grammar, and vocabulary. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

Laka, Itziar. 2006. Deriving split ergativity in the progressive: The case of Basque. In Ergativity: Emerging issues, eds. Alana Johns, Diane Massam, and Juvenal Ndayiragije, 173–195. Dordrecht: Springer.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2008. Morphological and abstract case. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 55–101.

Mahajan, Anoop. 1990. The A/A-bar distinction and movement theory. PhD diss., MIT.

Massam, Diane. 2001. Pseudo noun incorporation in Niuean. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 19: 153–197.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25: 273–313.

Ouhalla, Jamal, and Ur Shlonsky. 2002. Introduction. In Themes in Arabic and Hebrew syntax, eds. Jamal Ouhalla and Ur Shlonsky, 1–43. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic.

Perlmutter, David. 1968. Deep and surface structure constraints in syntax. PhD diss., MIT.

Polinsky, Maria, and Bernard Comrie. 2002. The biabsolutive construction in Nakh-Daghestanian. Manuscript, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Preminger, Omer. 2009. Breaking agreements: Distinguishing agreement and clitic doubling by their failures. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 619–666.

Preminger, Omer. 2011. Agreement as a fallible operation. PhD diss., MIT.

Rezac, Milan. 2011. Phi-features and the modular architecture of language. Vol. 81 of Studies in natural language and linguistic theory. Berlin: Springer.

Salanova, Andrés Pablo. 2007. Nominalizations and aspect. PhD diss., MIT.

Sigurðsson, Halldór Ármann, and Anders Holmberg. 2008. Icelandic dative intervention: Person and Number are separate probes. In Agreement restrictions, eds. Roberta D’Alessandro, Gunnar H. Hrafnbjargarson, and Susann Fischer, 251–280. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Byron Ahn, Sabine Iatridou, Anoop Mahajan, David Pesetsky, Masha Polinsky, Omer Preminger, Norvin Richards, Carson Schütze, and Tim Stowell for helpful discussions about this research. We also thank Laura McPherson and Kevin Ryan, whose fieldwork and morphological analysis of Senaya made this research possible, and their language consultant Paul Caldani, for sharing his love of his language with us. Our thanks also to Marcel den Dikken, two anonymous NLLT reviewers, and the insightful audiences at GLOW 35, WCCFL 30, and CLS 48. Authors are listed alphabetically. The first author was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalin, L., van Urk, C. Aspect splits without ergativity. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 33, 659–702 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9262-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9262-8