Abstract

Humanitarian emergencies such as armed conflicts are increasingly perceived as opportunities to improve mental health systems in fragile states. Research has been conducted into what building blocks are required to reform mental health systems in states emerging from wars and into the barriers to reform. What is less well known is what work and activities are actually performed when mental health systems in war-affected resource-poor countries are reformed. Questions that remain unanswered are: What is it that international humanitarian aid workers and local experts do on the ground? What are the actual activities they perform in order to enable and sustain system reform? This article begins to answer these questions through ethnographic case studies of mental health system reform in Kosovo and Palestine. Based on the findings, a theory of “practice-based evidence” is developed. Practice-based evidence assumes that knowledge is derived from practice, rather than the other way around where practice is believed to be informed by systematic evidence. It is argued that a focus on practice rather than evidence can improving system reform processes as well as the provision of mental health care in a way that is sensitive to local contexts, structural realities, culture, and history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humanitarian emergencies such as armed conflicts and natural disasters are increasingly described as opportunities for global mental health. WHO’s “Building Back Better” report, for example, states on its first page: “Emergencies, in spite of their tragic nature and adverse effects on mental health, are also unparalleled opportunities to improve the lives of large numbers of people through mental health reform” (2013:9). Similar reasoning has been voiced by a number of scholars. Patel et al. (2011) note that crises situations “[offer] the international humanitarian community a unique opportunity to create new services, or reorganize and reform pre-existing ones, so that short-term support may be transitioned into sustainable (mental health and psychosocial support) MHPSS programs” (p. 473). The science and technology journalist Greg Miller (2006) goes as far as to state, “often it takes a disaster to get mental health on the agenda”, and Shekhar Saxena, Director of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse at WHO, is quoted to have said that until something terrible happens, politicians do not think about mental health and therefore “our [the interventionists’] job (…) is systematically shaming them into thinking about it” (in Miller 2006:461).

Crises situations are indeed fertile grounds for mental health system reform in that they are often piggybacked on emergency interventions which are, in turn, driven by what Calhoun (2010) has called an “emergency imaginary”. According to him, such emergency imaginaries assume notions of suddenness, unpredictability, surprise, and shock, and are believed to demand urgent responses rather than political or economic analysis to improve lives. The emergency imaginary has been shown to create exceptional opportunities for medical humanitarian interventions in war affected settings by demarcating particular spaces, time frames, governance paradigms, and system accountability (for case studies see edited volume by Abramowitz and Panter-Brick (2015) and by introducing or further entrenching power hierarchies between expatriate humanitarian aid providers who tend to be in charge of interventions and local experts whose role is largely to implement rather than to lead the initiatives (Benton 2016; Last 2000; Locke 2015; Redfield 2005, 2013). In the mental health field, the emergency imaginary has been productive in specific ways having led to (a) an influx of financial resources into affected areas thereby making developments in mental health possible that have been hitherto unthinkable; (b) changing perceptions of dismantled health and mental health systems to view them as novel opportunities to build more person-centred systems of care; and (c) the mobilization of media attention and public sympathy to make mental health a priority (Epping-Jordan et al. 2015). Accordingly, emergency contexts are fruitful for decision-makers to be able “to allocate resources toward mental health and consider options beyond the status quo” (WHO 2013:13; Saraceno et al. 2007).

So far, research has been conducted into what building blocks are required to reform mental health systems in fragile states to be compatible with overall global mental health agendas. These include the provision of training for local mental health providers and the promotion of accessible mental health services by expanding community-based mental health care and downsizing long-stay psychiatric hospitals (Betancourt et al. 2013; Patel et al. 2011; Zwi et al. 2010). We also know about the barriers to such reform (mainly informed by the global mental health literature) including lack of funding, staff, medication, facilities, and, most importantly, political will (Prince et al. 2007; Saxena et al. 2007). What is less well known is what work and activities are actually performed when mental health systems in war-affected resource-poor countries are reformed. What is it that international humanitarian aid workers and local experts do on the ground? What are the actual activities they perform in order to enable and sustain system reform?

Interestingly, mental health system reform is seldom discussed specifically as work or practice and, consequently, its actual routine and mundane workings do not find their way into institutional history. Reasons for why the performative, practice-based element of such reforms has been mostly ignored are various. One that sticks out is the pressure exerted by funding agencies to focus on outputs and ‘evidence’ which is believed to underlie the emergency interventions and reform procedures. That is, mental health system reforms implemented in states emerging from crises are framed as following universal, consensus-based guidance and standards which, in turn, are considered to be based on scientific evidence. Overall, such guidelines call for key psychosocial interventions such as psychological first aid, emotional support, providing information, sympathetic reassurance, and the recognition of core mental health problems (Kienzler and Pedersen 2012). Equally, the scaling up of such initiatives from emergency interventions to mental health system reform is claimed to be in line with evidence-based global mental health standards for community-based mental health care (Pedersen et al. 2015). Hereby, the focus is on knowledge, guidelines, protocols, and plans in the abstract rather than their deployment in practice and the dialectic relationship with knowledge and context.

Practices that actually drive the intervention and reform processes are conspicuously absent from reports and academic publications. This is a crucial omission since by investigating and outlining such activities by individuals in specific contexts, it would be possible to discover what actually happens when mental health systems are reformed in war-affected countries. To achieve this, I propose to begin by questioning the dominant view of mental health system reform which foregrounds the implementation of ‘evidence-based practice’ and mainly highlights outputs. Specifically, I will turn ‘evidence-based practice’ on its head to investigate ‘practice-based evidence’ as it unfolds in concrete humanitarian situations. Practice-based evidence assumes that knowledge is derived from practice (a form of learning-by-doing), rather than the other way round where practice is believed to be informed by systematic evidence.

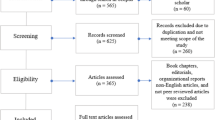

Focusing on practice-based evidence is important as it allows investigation of what actually happens by showing how variously positioned experts produce actions and, thereby, arrive at understandings of what is fitting or appropriate for the respective context. Practically speaking, this perspective could provide an inroad for improving actual reform processes as well as the provision of mental health care in a way that is sensitive to local contexts, structural realities, culture, and history. To illustrate my argument, I will work with two case studies derived from long-term ethnographic research in Kosovo (since 2004) and Palestine (since 2013). These two cases are particularly fitting as they are also featured in WHO’s (2013) “Building Back Better” report cited above where they serve as examples of the dominant view on mental health system reform. However, my data are different in that they focus on what international and local actors actually do when reforming mental health systems in their respective states. In both Kosovo and Palestine, I mapped organizations currently providing mental health care, conducted informal and semi-structured interviews with and observations among their staff, and analysed reports on mental health as well as pamphlets from nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and health service providers. I used ATLAS.ti software to explore, annotate, code, organize, and map my data and analysed them using thematic analysis.

In what follows, I will first outline the official and dominant narrative of what it means to “build back better” mental health care during and after emergency situations and then go on to introduce academic and interventionist views that have challenged this. Secondly, I will explore new avenues into understanding reform processes as practice by questioning the knowledge-action dichotomy and introducing a new perspective, inspired by the philosopher Cook and the policy scholar Wagenaar (2012), which perceives practice, knowledge, and context as relational processes. Thirdly, I will apply this shift in thinking to two case studies, namely, mental health system reforms in Kosovo and Palestine, in order to further elaborate how practice-based evidence rather than evidence-based practice shape reform processes. I will conclude by proposing a new perspective which views humanitarian and development practice, knowledge, and context as inherently relational and pragmatic rather than idealised reform processes as outlined in plans and protocols.

The Role of “Evidence-Based Practice” in “Building Back Better” Mental Health Systems

Opportunities for introducing and implementing health and mental health system reforms following emergency situations are rife in this day and age. With a rapid increase in wars and an ever-growing refugee crisis (UNHCR 2017), countries are facing new and severe humanitarian and health systems challenges. These challenges, in turn, are fuelled by new disease patterns. Many of the war-affected populations have recently undergone the epidemiological transition with non-communicable diseases and mental health problems heading the public health burden (Jones et al. 2009; Zwi et al. 2010). Their diagnoses, management and treatment face additional complexity in emergency situations due to the diseases’ chronic nature.

Mental disorders and psychosocial problems are attracting particular attention reflecting emerging evidence of increasing incidence and prevalence as well as more systematic recording practices and improved diagnostic techniques (Silove, Steel and Psychol 2006), along with the awareness that additional support services are required for persons suffering from acute trauma and distress (WHO 2003, 2013). Epidemiological surveys have made strikingly apparent that armed conflicts exacerbate the overall rates of mental disorders. A systematic review carried out by Tol et al. (2011) indicates an average prevalence of 15.4% (30 studies) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 17.3% (26 studies) for depression in conflict-affected populations (see also De Jong, Komproe and Van Ommeren 2003; WHO 2019). These rates are considerably higher than the average of 7.6% for any anxiety disorder and 5.3% for any mood disorder, which have been reported in the seventeen general populations participating in the World Mental Health Survey (Demyttenaere et al. 2004). Additionally, it is argued that severe mental disorders are on the rise in complex emergencies although prevalence rates are, in fact, unknown due to a lack of epidemiological research (Jones et al. 2009; Weine et al. 2005).

In order to fill this knowledge and intervention gap, scholars and interventionists advocate for immediate research, the implementation of evidence-based practice, and prioritizing of policies for adequate and sustainable mental health interventions during and in the aftermath of emergencies. For now, mental health interventions implemented during or immediately after emergencies mostly follow best-practice guidelines which are considered to be universal, standardized and evidence-based (Kienzler and Pedersen 2012). They include the Sphere Handbook (Sphere Project 2004), the “Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings” (Inter-Agency Standing Committee 2007), the WHO report “Mental Health in Emergencies” (2003), and the WHO report “Building Back Better. Sustainable Mental Health Care After Emergencies” (2003). These documents advocate for community-based mental health services that focus on counselling, community-based social supports, structured social activities, provision of information, psychoeducation, and raising awareness (Tol et al. 2011).

Once immediate crises are over, such emergency mental health interventions serve as basis for the development of extended mental health and psychosocial support programs and, related to this, institutional development (Abramowitz 2010). The focus is hereby put on the enhancement of (government) policies, human resources and training, programming and services, research and program monitoring, and finances (Ventevogel et al. 2011). Advocated best practices focus on community-based mental health approaches mirroring global mental health agendas implemented in development settings (for examples see Agani et al. 2010; Anckermann et al. 2005; Baingana and Ventevogel 2008; Bass et al. 2012; de Jong 1995; Doucet and Denov 2012; Eppel 2002; Igreja et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2007; Tol et al. 2008). Following the outline of the “WHO Service Organization Pyramid” (2007: http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/2_Optimal%20Mix%20of%20Services_Infosheet.pdf), emphasis is on self-care, informal community care, and primary mental health care at the base of the model. For persons requiring more intensive services, focused psychosocial supports are deemed appropriate while in-patient specialised services are to be reserved for the few suffering from severe mental disorders. Such approaches have been praised for being “affordable, effective, acceptable, and culturally valid” (Banatvala and Zwi 2000:103). Moreover, they are believed “to have great sensitivity to local culture, to be more able to demonstrate cultural competency, to use local outreach more effectively and to emphasize community participation in the development of healing networks of care” (Abramowitz 2010:364).

The implementation and governance of mental health and psychosocial support programs is often assumed to take place in humanitarian settings with weak or highly dysfunctional states (Good, Grayman and DelVecchio Good 2015). In such contexts, it appears to be possible for international organizations and their personnel to act in lieu of states rather than in close collaboration with them (Abramowitz 2015). However, researchers have begun to question this view highlighting that humanitarian mental health interventions also take place in strong state settings and that humanitarian work in such settings is necessarily framed and practiced differently. For example, Good, Grayman and DelVecchio Good (2015) have outlined the ways in which their team was required to adapt their mental health work to Indonesia’s strong institutional and bureaucratic structures by building meaningful cooperation with the government, especially the Ministry of Health, the public health system, and local health experts in order to produce successful outcomes. According to the authors, it is particularly important to acknowledge the different working conditions for humanitarians in strong versus weak state settings at a time where the role of humanitarian agencies is changing and debates are heated when it comes to legitimizing the focus on trauma, psychosocial interventions, and the development of mental health services.

It appears that WHO and other humanitarian actors are increasingly recognizing the importance of working with states when promoting mental health system reform with a focus on transitioning institution-based mental health care to a community-based approach. To this effect, WHO has created a “Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package” (http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/essentialpackage1/en/) containing training and advocacy modules. The goal is to reform systems by transferring knowledge about evidence-based practice and, thereby, change professional behaviour. Knowledge translation platforms, such as the one provided by WHO, are assumed to require an integrated effort by bringing together global research evidence and context-specific knowledge to inform mental health policies and persuade policy makers that the available evidence is both relevant and user-friendly (Yehia and El Jardali 2015; Moat et al. 2013). Thus, a linear approach emerges whereby knowledge is translated into guidelines, which, in turn, are expected to be adapted to local contexts before they are then implemented and evaluated.

Such approaches to mental health system reform are not particular to post-war situations. They are also widely adopted and further developed in the field of global mental health. In fact, medical humanitarianism and global health agendas have been shown to overlap in that they jointly influence international development, human rights advocacy, and international peacekeeping and diplomacy (Abramowitz and Panter-Brick 2015). What makes health system reform processes particular in humanitarian settings is that the “emergency imaginary” provides the opportunity for fast tracking reforms along the lines advocated. Exemplary cases where such a scenario has resulted in mental health system reform are listed in WHO’s “Building Back Better” report and include Afghanistan, Burundi, Indonesia, Iraq, Jordan, Kosovo, Palestine, Somalia, Sri Lanka, and Timor-Leste. What remains unclear from the report is what reforming mental health systems in such settings actually involved beyond the provision of training for mental and primary healthcare staff and restructuring of services, and how the emerging knowledge was channelled into broader developmental agendas by international and national organisations and experts. In other words, no insight is provided into the practices through which the reforms were brought about, evaluated, and sustained and to what extent systems were indeed built back better.

Critical Assessment of the “Dominant View”

The above outlined approaches to building back better mental health care following emergencies have not gone unchallenged. Both researchers and interventionists have criticized the approaches variously as top-down or even “imperialist” due to the fact that international actors implement them with limited options for local experts to collaborate (Summerfield 2012). Indeed, even proponents of the “dominant view” recognize that such top-down approaches pose the risk that “poorly designed policies and services may be introduced and may undermine local capacity, expertise, resilience and sustainability” (Zwi et al. 2010:339). Other researchers have attributed such shortcomings to (a) the lack of on-the ground coordination between the numerous governmental and non-governmental organizations (Weine et al. 2002); (b) the absence of evidence on whether or not the advocated practices are effective due to a lack of rigorous field testing of guidelines and standardized approaches (Ager 2002; Banatvala and Zwi 2000; Kienzler and Pedersen 2012); and (c) the lack of insight into the historical, political, social and cultural contexts within which mental health system reforms are carried out (Kirmayer 2005; Makhashvili, Tsiskarishvili and Droždek 2010; Summerfield 2003).

Debates surrounding appropriate ways of reforming mental health systems are ongoing and mostly concern questions as to whether or not such interventions are truly evidence-based and are socially and culturally appropriate or, in fact, wanted by the local communities (Pedersen, Kienzler and Guzder 2015; Pupavac 2004). Makhashvili, Tsiskarishvili, and Drožđek (2010) note pessimistically that “foreign assistance” causes, in the best case, “a devaluation of psychosocial aid in care recipients, whereas in the worse case, it results in a further deterioration of the psychological state of those who are already suffering and/or traumatized” (66). Instead, they along with other scholars argue for paying greater attention to the sociocultural contexts within which mental health problems are expressed and treatment protocols unfold (Kirmayer 2005), as well as to the long-term effects on health and local patterns of distress, help-seeking behavior, and healing (Abramowitz 2010; Friedman-Peleg and Goodman 2010; Pedersen 2002; Summerfield 2003; Weiss 2010).

In order to counter top-down mental health system reforms, empower users of mental health services as well as the communities they live in, and provide appropriate care, a two-tier approach is suggested. Tier one proposes that approaches should be deeply rooted in the community, combine both emic and etic approaches to diagnosis and treatment, and incorporate traditional healing practices to allow for a truly pluralist healthcare system to exist (de Jong 1995; Kirmayer 1989). Tier two advocates for increased access to political recognition and economic power so that individuals and communities can shape their own healing trajectories in meaningful ways (Campbell and Burgess 2012; Campbell et al. 2010). Campbell and Burgess (2012) summarize the underlying rationale by highlighting the need for “greater attention to the role of context and culture in framing how people experience and respond to threats to their wellbeing, greater recognition of the agency and resilience of individuals and communities, and the need to take more explicit account of the ways in which power inequalities undermine opportunities for health” (387). It is in meeting these challenges, they argue that community participation has a vital role to play.

While there clearly exist tensions between proponents of the ‘dominant view’ and critics who advocate for a more empowering “two-tier approach”, the debate has not reached a deadlock. In fact, I argue that this tension productively influences and, to a certain extent, even drives mental health reform agendas in conflict-affected settings. Indeed, those advocating for the ‘dominant view’ are conscious of the critique, deliberately expose themselves to it, and are taking some of the recommendations on board (Bemme and D’souza 2012). They openly recognize the lack of crucial information on cultural difference in expressions of distress and support the generation of culturally sensitive data on mental disorders and meaningful and feasible changes to mental health systems (Tol et al. 2011). Both parties to the discussion are, thus, calling for more locally relevant knowledge and understanding of how contextual factors help or hinder practice. In other words, all involved emphasize the importance of conducting long-term research projects to achieve cultural competency; using mixed-methods approaches to gain a better understanding of local needs, coping mechanisms, and conceptions of mental health; and designing community-based psychosocial interventions based on locally relevant evidence to empower both individuals and groups.

While such mutual learning is certain a positive sign, I want to challenge both parties to the debate on what should constitute meaningful and sustainable mental health system reform. Instead of advocating for more evidence-based practice, I argue that it is in fact not predominantly knowledge and understanding of context that shapes practice, but that practice itself generates knowledge and (impacts on) contexts. Through this shift in perspective, it would be possible to gain a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which mental health systems are reformed. In the following, I will outline what this shift entails by engaging with Cook and Wagenaar’s practice theory and applying it to two empirically researched case studies.

The Practice of Mental Health System Reform in Contexts of War and Conflict

Shifting the Focus from Knowledge to Practice

By shifting attention from evidence to practice, I am working toward developing a theory of “practice-based evidence” so as to show how practice brings about mental health system reform in specific humanitarian contexts. By illustrating this with two concrete cases, Kosovo and Palestine, it will become apparent that the respective reforms look somewhat different and a lot less coherent than presented in the ‘glossy reports’ produced by international organizations and governments.

To build the theory, I draw heavily on Cook and Wagenaar’s article “Navigating the Eternally Unfolding Present: Toward an Epistemology of Practice” in which they convincingly argue that it is not primarily knowledge and context that shape practice. Rather, they explain, knowledge and context emerge as artefacts from practice as people deal with uncertainty, complexity, and the limits of predictability. Accordingly, practice is seen as distinct and primary, which gives shape to knowledge and context and, thus, has an epistemic dimension in and of itself. Similarly, I want to argue that mental health system reforms in contexts of both crisis and development are less based on systematised knowledge or evidence than born out of situations where people do not know, or at least don’t completely know, what decisions to take, where the problems to be tackled are contested, and where the course of action is often rather unclear.

To develop this argument further, it is helpful to provide a brief overview of Cook and Wagenaar’s practice theory and highlight the kinds of questions it raises for the study of mental health system reform in contexts of war and conflict. According to the authors, it is traditionally assumed that when people engage in an activity, they “articulate the situation that confronts them as a particular kind of problem, after which they apply the relevant knowledge (…) that enable them to solve the problem” (4). Knowledge is, thus, understood to be applied in practice while context is believed to help or hinder the respective application. This, what they call Cartesian perspective, appears commonsensical to many, which is not surprising as it forms the basis for much of our work in government, higher education, and the business world (Tylor 1995a). Cook and Wagenaar set out to challenge this view by thinking through three main concepts that foreground practice: “actionable understanding”, “ongoing business”, and “the eternally unfolding present”.

“Actionable understanding” is based on the premise that as people undertake their often ordinary tasks of dealing with situations and organizing work, they engage in a “flow of activities” which in and of itself is not very eventful. Within this flow, they might get confronted with situations that obstruct or facilitate it—situations that evolve out of routine tasks and which require resolving through “actionable understanding” (19). To deal with or solve the respective matter does not require the application of knowledge, but rather to generate a form of practice within which new knowledge can emerge and/or existing knowledge is applied. In other words, “the value of knowledge lies in its utility within practice, not in a supposed ability to give rise to practice” (20). With regards to the study of mental health system reform in conflict-affected settings, this raises the questions: What forms of practice emerge within humanitarian settings that might generate new knowledge that could facilitate mental health system reform? What kind of knowledge is considered useful and by whom? How and by whom is knowledge applied in the reform process? What other tools, besides knowledge, are utilized by the actors involved to facilitate their practice and how do they, thereby, change the context within which they work?

This brings me to the author’s second concept, “ongoing business”. In life as in work, Cook and Wagenaar write, we seldom follow pre-determined policy mandates or blueprints like automatons. Instead, such mandates or rules only become apparent as the trajectory of the practice itself develops. They emerge out of “ongoing business”. As people go about their “business as usual”, they share experiences and activities collectively. Such action is habitual and particularly useful when navigating unpredictable situations as they do not require much overthinking. In other words, “the concept of ongoing business (…) points to a dynamic, developmental, often taken-for granted and unproblematic background against which and within which problems and opportunities of community’s practice arise and are dealt with” (21). While it might appear contradictory to think about “ongoing business” in situations that are driven by an “emergency imaginary” which requires thinking-on-one’s-feet, speedy decision-making, and quick acting, it is important to acknowledge that humanitarian interventions are, for the most part, enacted routinely and give rise to power-dynamics that go largely unquestioned. What then are the routine actions and understandings, environments, tools, predictable behaviors of stakeholders, and expectations of humanitarian practice? Put differently, what is it that we expect to be there, and which we tend not to give special attention? What happens when “ongoing business” gets disrupted and what forms of practice does this engender, what kind of knowledge gets deployed and/or generated? Who are the various actors and in what ways are they involved in particular practices and knowledge generation?

Finally, “the eternally unfolding present” draws our attention to the fact that negotiations, reform activities, and evaluations take place in the here and now. That is, there is usually not another dimension that undergirds practice as it unfolds; rather, immediate practice allows for actionable understanding to emerge and ongoing business to be sustained. From such a perspective, knowledge is neither static nor standardized, it cannot be stored and applied as soon as an optimal situation presents itself. In fact, the situation at hand does not contain a priori recognition rules that inform the actors what knowledge they need to apply (Tylor 1995b; Wagenaar 2004). Information that we possess only functions if we put it to use and is, in this very process, modified and, in some cases, radically altered. Of course, this does not mean that experts involved in reforming mental health systems in fragile states arrive at the scene without knowledge. Instead, I am arguing that they set to work and, thereby, put existing knowledge to use, generate new insights, and develop pathways through which to change the context they face. From this perspective, the idea of evidence-based practice is completely overloaded and, indeed, useless if one wants to understand how mental health system reform unfolds in the present. So how does practice contribute to knowledge and context in mental health system reform processes following emergencies? What new insights can be gained and made useful for other development contexts? What uncomfortable truths might come to light and how would an engagement with them allow us to enact humanitarian and development aid differently?

The above questions related to actionable understanding, ongoing business, and the eternally unfolding present will guide the following review of two case studies of mental health system reform in Kosovo and Palestine.

Case 1: Experimenting with Community-Based Mental Health Care in Kosovo

The Kosovo War in 1998/1999 led to a large-scale international humanitarian intervention campaign involving military, political, and aid responders who aimed at bringing an end to the war and its carnage (Kienzler 2012). Serbian forces had exerted extreme brutality against the Albanian population including large-scale killings and mass displacements. It is estimated that 10,000 were killed between March and June 1999, with the vast majority of the victims being Kosovar Albanians killed by Serbian forces. Rape and torture, looting, pillaging, and extortion were committed on a large scale. About 90% of the civilian population was forced to leave their homes and seek refuge abroad or inside Kosovo as internally displaced persons (Independent International Commission on Kosovo 2000).

In response to this unfolding humanitarian catastrophe, aid providers, including health professionals, rushed to the refugee camps that had sprung up at the border regions of Kosovo to provide protection, aid, and healthcare. Expecting to deal with injuries, malnourishment, and infectious diseases they had brought aid kits containing dressing material for fixing broken bones, cuts, and burns; supplements to improve the diets; and vital medication to curtail potential disease outbreaks. Yet, standard operating procedures and its routine actions, understandings, and tools were not what was required. Instead, aid responders were taken by surprise when the refugees mostly sought help for what appeared to be psychological distress connected to the gruesome violence that they had been forced to endure and witness (de Jong, Ford, Kleber 1999). Many felt utterly unprepared considering that they had received no mental health training. Taken aback by the extreme distress experienced by the refugees, some of the interventionists began, despite their lack of knowledge and expertise, to develop ad hoc psychiatric intervention strategies geared toward treating psychological trauma (Fassin and Rechtman 2009; de Jong, Ford and Kleber 1999).

A situation was, thus, encountered which demanded action by shifting gears rather than pressing on by applying pre-existing knowledge or evidence. It was a kind of gut reaction to suffering that drove humanitarians to swiftly generate new forms of practice and “actionable understandings”. Interestingly, however, what had started as a gut reaction became swiftly rationalized and institutionalized in that aid providers who were not necessarily trained in the field of mental health sought out Kosovar health professionals and volunteers in the refugee camps; provided them with training in the use of diagnostic manuals, scales, and treatment protocols; and integrated them in the line of humanitarian work mostly as assistants (Kienzler 2012). A Kosovar psychiatrist remembered during one of our conversations, “Foreign organizations brought us some forms [diagnostic checklists], as they were much more experienced with this. Through these questionnaires we could [more effectively] distinguish PTSD from other disorders. This made a great difference and I could change the way I worked.” Another psychiatrist showed me the questionnaires that they had used to capture traumatic events, emotions, and symptoms among the refugees. He contemplated, “In Albania, we had good conditions to do research. For example, in one camp there were 3500 refugees. They were located in one place. We entered there with questionnaires.”

These examples show that the immediate presence of humanitarian practice allowed for particular interactions with the world in that aid providers and local experts evoked, shaped, and deployed certain knowledges and, in doing so, changed, even created humanitarian and scientific spaces. In fact, the scientific practices that emerged in the folds of the of humanitarian aid provision as a new initiative are a textbook example of ‘actionable understanding’; knowledge in and through acting on the situation at hand. It was for the first time that prevalence rates and dynamics of trauma-related disorders could be established in situ, right behind frontlines of an ongoing war that disgorged traumatized individuals into the refugee camps and clinics of humanitarian aid providers, researchers, and their local assistants. In other words, the camp conditions imposed a particular order and practice of surveillance which enabled systematic population-based research and the generation of new scientific evidence.

The newly acquired insights, skills, and ways of working were further deepened and expanded after the war as humanitarian organizations followed the refugee population into Kosovo. They immediately began their work by implementing a variety of training and intervention strategies and programs (Pupavac 2002, 2004). Within this context, mental health experts arrived to lecture, organize workshops, administer exams, and provide certificates. At the same time, more research was being conducted to establish prevalence rates of mental disorders and survey therapeutic treatments among the general population. Epidemiological studies found high levels of psychopathological distress and elevated rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety among civilians due to war exposure (Eytan et al. 2004; Cardozo et al. 2003; Morina, Rushiti, Salihu and Ford 2010).

During this time, mental health gained unprecedented attention. As a WHO (2003) reflected, it was precisely due to the war that local stakeholders “became receptive to considering new approaches” and international human and financial resources were made accessible for research and training (63–64; see also Weine et al. 2005). During what has been described as the organization’s largest operation in the world at the time (WHO 2001), a mental health unit as part of the UN Kosovo Team (UNKT) was established and a rapid assessment conducted to understand the country’s mental health needs. This was followed by a Mental Health Strategic Plan (approved in 2001) which foresaw the transformation of Kosovo’s asylum in Shtime into a Centre for Integration and Rehabilitation, the building of Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs) in all the country’s regions, and training mental and primary healthcare providers in diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care.

Less clear was how to actually implement these reforms on the ground as no blueprints or illustrative case studies were available. New “actionable understandings” had to be found to improve mental health. For instance, interventionists experimented with self-help groups for families with persons with severe mental disorders which had been shown to be effective in very different social contexts such as HIV/AIDS prevention in the United States (Weine et al. 2005). New partnerships were formed as WHO began to collaborate with the University of Illinois at Chicago as well as with Kosovar mental health professionals in order to draw up a plan for mental health services following a community-based approach focusing on families, resilience, and professional collaboration. This program led to the development of professional teams at local CMHCs and, in 2006, the overall program was implemented in Kosovo’s health system (Griffith et al. 2005). In parallel, a group of researchers and interventionists from the United States partnered with Kosovar psychiatrists to create psychoeducational multi-family group programs in the newly built CMHCs for families of persons with severe mental illness to improve access to treatment, combat stigma, and raise awareness. This initiative led to a change in policy at the level of the Kosovar Ministry of Health which now required the establishment and funding for multiple-family groups and family home visits in each of the CMHCs (Weine et al. 2005). It was, thus, hoped that it would be possible to address the public mental health needs of Kosovars and “to build a system (…) under conditions of low resources” (18).

Over 10 years on, the country’s mental health system has been described as vibrant due to “the focus on sustainability and the commitment of local health professionals” (Epping-Jordan et al. 2015). Yet, when one reads WHO reports that form part of the organization’s ‘grey literature’ rather than the ‘glossy report genre’, one can learn that already in 2001 huge financial cuts were made to the intervention resulting from the shift from the emergency situation to a development operation and “demands for emergency funds elsewhere in the world”. Reflecting on this situation, the director of a CMHC confirmed this by telling me that since the “internationals left to Afghanistan” his centre was hardly able to come up with the necessary funds to pay its employees and finance the treatments and programmes offered to patients. Similarly, a psychiatrist working for a local mental health NGO reasoned, “During the postwar period most of the mental health centers did not exist and a lot of funds, donations, and support went into those. Once the buildings were built, not enough money was invested into resources and capacities inside.” It can be speculated that this was partly because mental health is underrecognized and underfunded almost everywhere, including in so-called high-income countries, and that consequent organizational routines of mental healthcare were reproduced also in Kosovo.

Consequently, there is currently a severe lack of human resources with some figures indicating 1.9 psychiatrists, 0.3 psychologists, 8.8 psychiatric nurses, and 0.5 social workers/counselors per 100,000 population (UNKT 2007). Moreover, government spending on mental health is low, which makes long-term and follow-up treatment difficult. Until this day, CMHCs depend on foreign donations and training programs, as only a two percent of an already under-funded health care system is devoted to mental health. International donors and training providers, in turn, encourage Kosovar mental health practitioners to follow evidence-based diagnostic practices and treatment procedures in an attempt to provide quality care nevertheless (WHO 2013). While well meaning, such encouragement shows little regard for what it actually means to follow standards when fundamental resources are lacking and donors earmark funds for artefacts such as workshops and buildings rather than for operating costs such as salaries, ongoing routine practices of treatment and care, and drug supplies.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to conclude that the reforms and related activities were unsuccessful per se—they did, after all, improve access to mental health care and the provision of services despite challenges related to financing, training and coordination. As I was able to show, the reform activities created new practices, valuable epidemiological data, mental health awareness among the population, and insights into ways in which mental health systems could be transformed from institution-based ones into community-based ones in crises situations. They also delivered ‘lessons learned’ that could be applied elsewhere in the world where similar reform opportunities presented themselves in contexts of emergency. Thus, by focusing on practice and its iterative relationship with knowledge and context, it is possible to bring to light what it takes to reform systems in fragile situations including the ad hoc responses to unexpected mental health problems, the organization and coordination of research activities under pressure, the experimenting with various approaches to health care and system changes, and the working and related frustrations under resource-scarce and uncertain conditions. Unfortunately, these insights are rarely, if ever, reflected on in the process of streamlining practices into protocols and guidelines and, thus, fail to explicitly inform practices in new locales.

Case 2: Lessons Learned or Learning-by-Doing in Palestine’s Mental Health System Reform?

As WHO was scaling down the intervention in Kosovo, its headquarters in Geneva received an inquiry from the Palestinian Ministry of Health asking for a situational analysis of the mental health of the population and the functioning of the mental health system (WHO 2010). The reason for reaching out was that human rights organizations and health providers had reported an alarming increase of distress and trauma-related mental disorders connected to the ongoing Second Intifada (Palestinian uprising, 2000–2004) and, particularly, to Israel’s exertion of extreme violence including the demolition of houses and bombardment of residential areas, an increase in detentions and torture, and the killing of more than 3135 Palestinians (Giacaman et al. 2009).

WHO responded by sending Benedetto Saraceno, then Director of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, to head the situational analysis. He deployed the World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS), a tool that had been developed to collect information on mental health systems. As data collection progressed, findings emerged that drew attention to particular system gaps and recommendations for future reform (WHO 2010). Specifically, it was revealed that the Ministry of Health concentrated 90% of its staff and budgets and 100% of its inpatient beds in tertiary psychiatric care at the Bethlehem Psychiatric Hospital and Gaza Nasr Hospital. Moreover, primary health workers were deemed to have close to no training in diagnosing and treating mental disorders, and very little investment had been made in community-based care for persons suffering from mental disorders besides PTSD (WHO 2013). With these shortcomings in mind, WHO formulated an operational plan, which was signed by the Palestinian Ministry of Health, the WHO, and the French and Italian development organizations. Their joint objective was “developing, reorganizing, improving and expanding current mental health services according to a community-based mental health approach” (WHO 2009:21). This included limited funding from the European Union for the building of CMHCs, the formulation of a mental health policy, an Anti-Stigma Campaign, and the formation of a Family Association.

While such initiatives had appeared “experimental” immediately after the Kosovo War, they had achieved a character of “ongoing business” in conflict-affected Palestine. However, this is not to say that reform practices in Palestine were solely informed by existing knowledge and experience gained in other fragile states. Rather, interventionists used knowledge as tools to facilitate practice and give work “a specific character” (Cook and Wagenaar 2012, 25). The specific character was largely shaped by the politically fragile context that put serious constraints on the implementation of standard operating procedures and routine policy instruments. In fact, the shifting context required practitioners to improvise on the spot and arrive, time and again, at new “actionable understandings” in order to push reform processes forward. Thus, the emerging practices continued to have a strong learning-by-doing character as there was no guideline or otherwise agreed upon plan of how to achieve system reform in a volatile and constantly shifting political context. According to WHO’s “Building Back Better” report, key practices entailed (a) providing mental health training to health workers, including nurses, in primary health clinics and newly established community-based mental health centres; (b) responding ad hoc to crisis situations resulting from violence and loss due to the military occupation and the resistance against it; (c) developing a unified directorate of mental health to manage community-based and hospital mental health services across the West Bank and Gaza despite their physical separation and inability of policy makers, health providers and, in many cases, international aid personnel to travel between the two places; and (d) delivering services while struggling with regular funding shortages.

The implementation of these initiatives was not straightforward as large-scale politics (rather than scientific evidence or best-practice guidelines) determined where the reform processes were heading. For instance, in 2006 the reform came to a grinding halt as all direct financial support was withdrawn following the democratic election of Hamas, which was identified by Western nations as a terrorist organization with which the donor countries refused to formally interact. I was told, “When the elections happened, we were [supposed to receive] the project [funding] from the EU. But, they had frozen the funds so we were affected and this delayed the [reform] to start.” Consequently, the building of CMHCs was suspended and the mental health policy remained unfinished, making it impossible for mental health professionals to provide community-based mental health care (Kienzler and Amro 2015). The situation changed again in 2007, when Mahmoud Abbas formed a government in the West Bank. As a result of this political shift, the WHO could apply for funding from the EU to underwrite the implementation of the mental health policy. Funding was provided in two relatively short phases (2008–2011 and 2011–2015) which was not sufficient to fully integrate mental health into primary healthcare as had been the plan.

In this scenario practice appears to be indeed shaped by the international and national political contexts rather than the other way around as Cook and Wagenaar’s practice theory would suggest. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to assume that interventionists and health providers solely reacted within a given context. Instead, they acted in what the authors call the “eternally unfolding present” as they opened up new spaces for the organization, management, and treatment of mental health. For instance, local NGOs started to play an important role in the delivery of training and health care due to their flexible nature that allowed them to creatively work within contexts of fluctuating funding and expertise. Having first emerged in the social action movement of the 1980s, their agenda had long been directed at building Palestinian services and, through this, resisting to occupation and calling for justice (Giacaman, personal conversation). As we have previously shown, they were able to build new networks among mental health providers in order to prevent the duplication of services; started to build pathways for referrals between NGOs, UNRWA and the Ministry of Health; improved the provision of treatment by organising international and national training sessions and recording best-practices; and developed fund-raising skills and mechanisms to continue their work despite depleting international aid (Kienzler and Amro 2015). A testament to their enormous productivity is our recently created comprehensive directory of 21 NGOs working in the field of mental health and psychosocial support across the entire West Bank (http://icph.birzeit.edu/research-intervention-tools/mental-health-and-psychosocial-directory-mhpss-west-bankopt). It highlights a diverse range of treatment strategies ranging from pharmacological treatment; to different forms of psychotherapy with a focus on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), narrative therapies, and Eye-Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR); psychosocial support; rehabilitation services for those with physical disabilities; socio-educative services, school-based counselling and inclusive education; and community engagement such as awareness raising, advocacy, empowerment and anti-stigma campaigns. While these services are mostly directed at all affected demographic groups with a focus on those with low socioeconomic status (10 NGOs), a smaller number of NGOs focuses on specific groups such as children and adolescents (6 NGOs); survivors of political violence and torture (2 NGOs); and women (2 NGOs).

As expertise is increasing and the mental health system is strengthened, myriad challenges continue to exist. First of all, all mental health providers we talked to criticized the relatively unstable “project like character” of the mental health system reform. They lamented the fact that international donors only fund time-limited projects directed at particular populations that promise concrete and preferably measurable outcomes. This, they said, hampered the development of long-term relations between service providers and clientele as well as the creation of a sustainable mental health program. Similar to the situation in Kosovo, it requires the heightened state of emergency to free up funding for system building—system development as such is not “urgent” enough to warrant the distribution of resources on a regular basis.

Additionally, other individual service providers we talked to spoke openly about their perception of the current state of the mental health system. To give insight into their discontent, the following themes and quotes are illustrative as health providers mainly criticized: (a) donor dependency, short-term projects and financial challenges—“What stresses us out is that we don’t have enough funding to continue with a particular service or continue with the idea of a project”; (b) movement restrictions and accessibility—“Of course the political context is a major problem. For example, we sometimes can’t have access to some of the centres, especially those located in villages because the Israeli military closed the access. Sometimes we can’t have group activities in our centres because there might be teargas all around”; (c) lack of professional and academic training—“We face a lack of good academic training for people working in mental health. For example, when we employ new people in our centre, we have to spend a long time training them [on the job] because there is a big lack of practical training at the university”; (d) stigma in the community—“There is shame or stigma when it comes to attending a mental health workshop or seeing a psychiatrist”; and (e) waning support for vulnerable groups in the society—“I think that we are changing (…) to a less supportive community. (…) People had enough. They can’t think of others (…), every person is stressed, it’s so stressful for all of us what is happening [economically and the occupation related restrictions and violence]. So people reach the point where they don’t have enough energy to share with others. [They feel] ‘I, me by myself need more’. People can’t take it anymore”. All these factors were perceived to disrupt emerging routines requiring such workers to adapt or develop new practices and deploy knowledge in innovative ways.

Moreover, health workers often scathingly criticized the lack of political will in the Ministry of Health which turned both institution building and clinical practice into a struggle. Indeed, a person working for the mental health unit in the MoH told me, “policy makers in health, give lip service to mental health.” They elaborated this stating that both the MoH and policy makers tend to divert money earmarked for mental health to other health sectors which, in turn, exacerbates the underfunding of the mental health system resulting in a lack of staff, medication, and facilities. Additionally, they explained that often not the most capable staff are employed in the mental health sector and that even underperforming staff in more prestigious health fields are “bumped down” to the mental health unit. Sarcastically they said, “It’s like the island of the despised, yeh?” Finally, with regards to infrastructure, they revealed how it came to be that the Mental Health Unit was recently moved from the expensively renovated CMHC in Ramallah (which I had visited 5 years earlier) to a comparatively shabby part of town:

Mental health generates a lot of projects and money for the Minister of Health and for a while they keep nice offices, they buy furniture and equipment, and some centres were established to be mental health centres and mental health facilities. But soon after the project is over, the Ministry of Health takes over these territories and sends the people working in mental health to places where accessibility is a problem.

Amidst these scandals and systemic weaknesses, health providers did not lack imagination on how they would like the situation to be improved. They called for (1) increasing cooperative efforts to improve coordination between the different stakeholders working in the mental health field; (2) establishing a strong educational system to improve psychiatry and psychology training through the revision of the university curricula, the establishment of international exchange programs, and a properly functioning residency program; and (3) investing in long-term development rather than short-term emergency interventions. However, the question remains, how funding could be made to last long enough to both absorb immediate and longer-term development needs during the ongoing crisis situation. The responses of study participants show that as their work unfolded in the present, it was both informed by the past through knowledge as well as future aspirations. However, they went even further claiming that systemic change and development would need to rest on political solutions beginning with political stability through the end of the Israeli occupation; reparations for decades of injustice, human rights abuses and the imposition of barriers for development; and the international recognition of the State of Palestine. At the same time, they were acutely aware that their visions were merely aspirational as the international community was not ready to commit to long-term, sustainable development in such a complex and often unpredictable context. It becomes, thus, apparent that the practice involved in mental health system reform in a fragile and conflict-affected state like Palestine does not primarily rest on scientific evidence or best-practice guidelines. It emerges through a creative combination of routine practices, experimentation, adaptation, and knowledge application in the present which, in turn, brings together both past experiences with ambitions located in the future. Through this complex process, new forms of knowledges and contexts are created resulting in what I want to call “practice-based evidence” which is the real driver of system reform and possibly even mental healthcare in fragile states.

Towards a Theory of “Practice-Based Evidence”

Based on the case studies presented, I am calling for a rethink of the role of ‘evidence’ when it comes to mental health system reform and the provision of community-based care in order to gain a better understanding of what actually happens when systems are reformed in contexts of emergency and fragility. In other words, I propose a theory of ‘practice-based evidence’.

To unravel this further, I want to return to the very beginning of the article where I discussed perceptions of humanitarian emergencies as ‘opportunities’ for mental health system reforms. Opportunity in such arguments is directly linked to ‘action’ and not primarily to reflection or analysis. This is in line with the concept of ‘opportunity’ itself which, according to the Oxford Dictionary, refers to an occasion or situation that makes it possible to do something that one wants to do or has to do, or the possibility of doing something. The “possibility of doing something” in the aftermath of political violence is, as I was able to show, driven by an “emergency imaginary” which suggests that immediate action rather than analysis is required. In Milton Friedman’s words: “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around” (1962:ix).

Crises have been shown to lead to heightened industriousness among various actors. In the contexts of both Kosovo and Palestine, this became apparent as international and national actors speedily freed material resources, changed attitudes of policy makers to embrace the possibility of system reform, and mobilized media attention and public sentiment to accelerate action on the ground. In an extremely short period of time, researchers and interventionists collected, analyzed, and reported data reflecting the mental health situation on the ground (situational analyses); drew up action plans and signed memoranda of understanding; built entirely new infrastructures including the establishment of community-mental health centers in every major region, the delivery of accredited training courses, and a newly trained work force in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare; and performed novel forms of community-based mental health treatment.

Such hyper-productivity is not uncommon in complex and unpredictable contexts. For instance, Naomi Klein (2007) writes with regards to crises situations in Iraq, Sri Lanka and the US that “every time a new crisis hits (…) the fear and disorientation that follow are harnessed for radical social and economic re-engineering” (49). That is, as core functions of government break away during crises situations, new funding schemes and actors appear on the scene taking the liberty to enter into communities in order to revamp institutional structures and practices. In the field of mental health, they have been shown to re-engineer health systems and reshape how people relate to suffering, mental illness, and treatment when they, the humanitarian aid providers, might not have been invited or appreciated to do so under more mundane circumstances (Pupavac 2002, 2004).

Crisis-laden contexts can thus be seen as productive tools which are put to work by actors who animate certain elements of their environment that allow them to move particular situations forward in a productive way. The case of mental health system reform in war-affected settings has shown that this involves habits and routines (ongoing business); thinking and acting on one’s feet as well as improvisation to arrive at something like an actionable understanding; and a being in the present that brings past experiences together with future aspirations (eternally unfolding present). What this ongoing relationship between the actors and their environment requires in order to bring about meaningful change is not easily, if ever, fully predictable. What then does it take to keep situations from slipping into chaos even in contexts that often appear chaotic due to political and economic instability, violence, and social fragmentation?

In an earlier article, Wagenaar (2004) notes with regards to a very different context that this puzzle resides in the “unrecognized assumptions of the observer—in particular, in the pervasive Cartesian bias in our culture that suggests that mastering a particular situation is equal to knowing it” (649). Yet, in both Kosovo and Palestine actors were far from knowing the situations they were facing. Indeed, they were often unprepared for what they were confronted with and did not initially know what decisions to take. In the case of Kosovo, the delivery of mental healthcare and psychosocial support in refugee camps was based on gut reactions when aid providers were shocked into action upon witnessing the emotional distress expressed by their patients. They swiftly designed treatment protocols, trained capable refugees in therapeutic methods, and drew up agendas for research to enhance knowledge on mental health prevalence rates, risks, and intervention requirements. In the aftermath of the Kosovo War, the emerging results and expertise were employed as tools in the process of system reform. The mental health system reform itself was achieved through varied attempts until some success was achieved (the main principle of trial and error) and lessons-learned emerged that could be exported to other parts of the world such as Palestine. While the reform processes in Palestine appeared similar on the surface, they had to be enacted differently considering the ongoing conflict and large-scale international politics which, depending on the situation at hand, enabled or shut down financial and technical support. Consequently, the reform practices resulted in yet again new knowledge and the creation of unique contexts in which NGOs pressed forward thanks to their relative political independence and flexibility. Indeed, Palestinian and international NGOs rather than government institutions strengthened the health system and provided professional training to Ministry of Health workers, designed referral pathways, and began to deliver state-of-the-art psychiatric treatment and psychosocial support to beneficiaries.

This is not to say that guidelines or scientific evidence were irrelevant—they were just not blueprints for action. Instead, they were tools with which actors engaged in order to help them to push mental health system reforms forward against the odds of funding shortages and lack of political will. Thus, for guidelines or evidence to be useful they had to enter into a dynamic relationship with practice, knowledge, and context. Unlike what is propagated in the glossy reports of international and national organizations, this relationality did not necessarily bring about ideal or best possible outcomes (according to the circumstances). Rather, it reveals the ways in which interventionist act on situations and move about in what Wagenaar refers to as the “moral-political environment of high uncertainty” (650). Thus, WHO’s rhetoric of “building back better” has to be questioned in that it has a tendency to provide a false sense of optimism and the illusion of meaningful, even verifiable betterment. Additionally, the rhetoric hides or brushes to the side uncomfortable matters such as the ‘laboratory character’ of aid provision, the shattered dreams of sustainability, and the unequal power dynamics among differently positioned actors. Indeed, anthropological critique of medical humanitarianism has pointed out that its interventions create or deepen dependencies, neglect to address political and economic conditions ultimately responsible for people’s suffering and ill health, entrench inequalities along gendered, cultural and economic difference, and fail to confront structural racism and white supremacy within the aid field (Abramowitz and Panter-Brick 2015; Benton 2016; Redfield 2013). At the same time, a focus on practice debunks critics of the dominant view in that reform processes are not simply imposed top-down on conflict-affected countries. On the contrary, I show that local experts play a paramount role, despite their unequal status, in terms of inviting, hosting, participating in, and shaping international interventions. The two cases demonstrate that the reforms are to certain degrees coproduced across countries, disciplines, and individual actors and, thereby, engender relatively flexible and situational knowledges. In both countries new knowledge and evidence was created that helped to improve mental healthcare delivery not only locally, but, as I hypothesize, in other emergency situations as well.

To explore these practices across space and time requires further multi-site research and engagement with various actors and sources of inquiry in order to not misrepresent the field. First, humanitarian organizations are hugely diverse and, it has been shown that there is a difference in their working depending on the respective state settings (i.e. mental health interventions are carried out differently in weak versus strong state and bureaucratic settings) (Good, Grayman and DelVecchio Good 2015). Second, it is crucial to base one’s investigation on diverse information sources—was one to focus solely on publications, websites, or conversations with official proponents of mental health reform agendas, one’s view would be skewed. That is, one might be enticed by their claims related to the importance of conducting long-term research projects to achieve cultural competency; using mixed-methods approaches to gain a better understanding of local needs, coping mechanisms, and conceptions of mental health; designing community-based psychosocial interventions to empower both individuals and groups; addressing social determinants of mental health through initiatives such as microcredit programs; and raising awareness to combat stigma. Yet as actors in the international mental health field know full well, such long-term engagement is close to impossible to achieve in most contexts. Instead, intended sustainable program development is more often than not reduced to a project-like patchy effort to change professional practices. Unlike programmes, projects can react more flexibly to frequent changes in administration and funding interruptions due to their narrowly set goals and predefined end-dates (Jacobsen 2014)—a necessity when working in the both the humanitarian and development sectors. What it takes to understand the various ways in which mental health systems are reformed and treatment delivered in different national contexts is a move away from a focus on “evidence-based practice”. Embracing “practice-based evidence” could produce valuable insights into how health system reforms proceed in “real life”; how the reforms might or might not be linked into local and global bureaucratic structures; how reform practices might affect other areas of policy and practice not immediately related to heath and medicine (i.e., social welfare, housing, education); what effect these processes have on professional practice and how this is experienced by health practitioners; what these systematic and practical changes are doing to intended beneficiaries and their mental health outcomes over the long-term; whether or not reforms and changing practices empower local groups and what new forms of actions might emerge as a consequence; and what the unintended consequences are of practices engaged in system reform. In a first step, such practice-based evidence would allow us to explore more fully the complexity of building health systems and practices of delivering mental health care in settings affected by conflict, instability, and resource-scarcity. In a second step, it would be important to put emerging new insights to the test by exploring whether or not such evidence actually leads to improved access to healthcare, professional practice, and effective and, importantly, valued care for those in need.

References

Abramowitz, Sharon A. 2010. “Trauma and Humanitarian Translation in Liberia: The Tale of Open Mole.” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 34 (2): 353-379.

Abramowitz, Sharon A. 2015. What Happens When MSF Leaves? Humanitarian Departure and Medical Sovereignty in Postconflict Liberia. In: S. A. Abramowitz and C. Panter-Brick (eds.) Medical Humanitarianism Ethnographies of Practice, pp. 137–154. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Abramowitz, Sharon A. and Catherine Panter-Prick. 2015. “Bringing Life into Relief: Comparative Ethnographies of Humanitarian Practice”. In: S. A. Abramowitz and C. Panter-Brick (eds.) Medical Humanitarianism Ethnographies of Practice, pp. 1-19. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Agani, Ferid, Judith Landau, and Natyra Agani. 2010. “Community‐Building Before, During, and After Times of Trauma: The Application of the LINC Model of Community Resilience in Kosovo.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 80 (1): 143–149.

Ager, A. 2002. “Psychosocial Needs in Complex Emergencies.” The Lancet, 360: s43–s44.

Anckermann, Sonia, Manuel Dominguez, Norma Soto, Finn Kjaerulf, Peter Berliner, and Elizabeth Naima Mikkelsen. 2005. “Psycho-Social Support to Large Numbers of Traumatized People in Post-Conflict Societies: An Approach to Community Development in Guatemala.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 15 (2): 136–152.

Baingana, Florence, and Peter Ventevogel. 2008. Mental Health and Psychosocial Interventions and Their Role in Poverty Alleviation. Proceedings of a Conference. Intervention 6(2):167–173.

Banatvala, Nicholas, and Anthony Zwi. 2000. “Conflict and Health: Public Health and Humanitarian Interventions: Developing the Evidence Base.” British Medical Journal 321 (7253): 101.

Bass, Judith, Bhava Poudyal, Wietse Tol, Laura Murray, Maya Nadison, and Paul Bolton. 2012. “A Controlled Trial of Problem-Solving Counseling for War-Affected Adults in Aceh, Indonesia.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 47 (2): 279–291.

Bemme, Doerte, and Nicole D’souza 2012 Global Mental Health and its Discontents. Somatosphere. http://somatosphere.net/2012/07/globalmentalhealthanditsdiscontents.html, accessed July 19, 2018.

Benton, Adia. 2016. “African Expatriates and Race in the Anthropology of Humanitarianism.” Critical African Studies 8 (3): 266-277.

Betancourt, Theresa S., Ms Sarah E. Meyers-Ohki, Ms Alexandra P. Charrow, and Wietse A. Tol. 2013. “Interventions for Children Affected by War: An Ecological Perspective on Psychosocial Support and Mental Health Care.” Harvard Review of Psychiatry 21 (2):70–91.

Calhoun, Craig. 2010. “The Idea of Emergency: Humanitarian Action and Global (Dis)order. In Contemporary States of Emergency: the Politics of Military and Humanitarian Interventions, edited by D. Fassin and M. Pandolfi, 29-58. New York: Zone Books.

Campbell, Catherine, and Rochelle Burgess. 2012. “The Role of Communities in Advancing the Goals of the Movement for Global Mental Health.” Transcultural Psychiatry 49 (34): 379–395.

Campbell, Catherine, Flora Cornish, Andrew Gibbs, and Kerry Scott. 2010. “Heeding the Push from Below How Do Social Movements Persuade the Rich to Listen to the Poor?” Journal of Health Psychology 15 (7): 962–971

Cardozo, Barbara Lopes, Reinhard Kaiser, Carol A. Gotway, and Ferid Agani. 2003. “Mental Health, Social Functioning, and Feelings of Hatred and Revenge of Kosovar Albanians one Year After the War in Kosovo.” Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 16 (4): 351-360.

Cook, SD Noam, and Hendrik Wagenaar. 2012, “Navigating the Eternally Unfolding Present: Toward an Epistemology of Practice.” The American Review of Public Administration 42 (1): 3-38.

de Jong, Joop. 1995. “Prevention of the Consequences of Man-Made or Natural Disaster at the (Inter) National, the Community, the Family and the Individual Level.” In Extreme Stress and Communities: Impact and Intervention, pp. 207–227. Springer, Berlin.

De Jong, Joop TVM, Ivan H. Komproe, and Mark Van Ommeren. 2003. “Common Mental Disorders in Postconflict Settings.” The Lancet 361 (9375): 2128-2130.

De Jong, Kaz, Nathan Ford, and Rolf Kleber. 1999. “Mental Health Care for Refugees from Kosovo: the Experience of Médecins Sans Frontières.” The Lancet 353 (9164): 1616-1617.

Demyttenaere, Koen, Ronny Bruffaerts, Jose Posada-Villa, Isabelle Gasquet, Viviane Kovess, Peal Lepine, Matthias C. Angermeyer, Bernert S, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T 2004. “Prevalence, Severity, and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys.” Jama 291 (21): 2581-2590.

Doucet, Denise, and Myriam Denov. 2012. “The Power of Sweet Words: Local Forms of Intervention with War-Affected Women in Rural Sierra Leone.” International Social Work 55 (5): 612–628.

Eppel, Shari. 2002. “Reburial Ceremonies for Health and Healing After State Terror in Zimbabwe.” The Lancet 360 (9336): 869–870.

Epping-Jordan, JoAnne E., Mark Van Ommeren, Hazem Nayef Ashour, Albert Maramis, Anita Marini, Andrew Mohanraj, Aqila Noori, Rizwan H, Saeed K, Silove D, Suveendran T 2015. “Beyond the Crisis: Building Back Better Mental Health Care in 10 Emergency-Affected Areas Using a Longer-Term Perspective.” International Journal of Mental Health Systems 9 (1): 15.

Eytan, Ariel, Marianne Gex-Fabry, Letizia Toscani, Lisa Deroo, Louis Loutan, and Patrick A. Bovier. 2004. “Determinants of Postconflict Symptoms in Albanian Kosovars.” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192 (10): 664-671.

Didier Fassin, Richard Rechtman. (2009). The Empire of Trauma An Inquiry into the Condition of Victimhood. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Friedman, Milton. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman-Peleg, K., Y.C. Goodman 2010. From Posttrauma Intervention to Immunization of the Social Body: Pragmatics and Politics of a Resilience Program in Israel’s Periphery. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 34(3): 421–442.

Giacaman, Rita, Rana Khatib, Luay Shabaneh, Asad Ramlawi, Belgacem Sabri, Guido Sabatinelli, Marwan Khawaja, and Tony Laurance. 2009. ‘Health Status and Health Services in the Occupied Palestinian Territory’. Lancet 373 (9666): 837–49.

Good, Byron, Jesse Hession Grayman and Mary-Jo DelVecchio Good. 2015. “Humanitarianism and “Mobile Sovereignty” in Strong State Settings: Reflections on Medical Humanitarianism in Aceh, Indonesia. In: S. A. Abramowitz and C. Panter-Brick (eds.) Medical Humanitarianism Ethnographies of Practice, pp. 155-175. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Griffith, James L., Ferid Agani, Stevan Weine, Shqipe Ukshini, Ellen Pulleyblank‐Coffey, Jusuf Ulaj, John Rolland, Afrim Blyta, and Melita Kallaba. 2005. “A Family‐Based Mental Health Program of Recovery from State Terror in Kosova.” Behavioral Sciences and the Law 23 (4): 547-558.

Igreja, Victor, Wim C. Kleijn, Bas JN Schreuder, Janie A. Van Dijk, and Margot Verschuur. 2004. “Testimony Method to Ameliorate Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Community-Based Intervention Study with Mozambican Civil War Survivors.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 184 (3): 251–257.

Independent International Commission on Kosovo. 2000. The Kosovo Report: Conflict, International Response, Lessons Learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee 2007 IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Inter-Agency Standing Committee.

Jacobsen, Kathryn. 2014. Introduction to Global Health. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Lisa M. Jones, H. A. Ghani, A. Mohanraj, Shannon Morrison, Peter Smith, and D. Stube. 2007. Crisis into Opportunity: Setting up Community Mental Health Services in Post-Tsunami Aceh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium for Public Health 19:60.

Jones, Lynne, Joseph B. Asare, Mustafa El Masri, Andrew Mohanraj, Hassen Sherief, and Mark Van Ommeren. 2009. “Severe Mental Disorders in Complex Emergencies.” The Lancet 374 (9690): 654-661.

Kienzler, Hanna. 2012. “The Social Life of Psychiatric Practice: Trauma in Postwar Kosova.” Medical Anthropology 31 (3): 266-282.

Kienzler, Hanna and Zeina Amro. 2015. ‘Unknowing’and mental health system reform in Palestine. Medicine Anthropology Theory 2 (3): 113-127.