Abstract

Hybrid organizations’ success should effectively fulfill both beneficiaries’ and customers’ needs, requirements, and expectations, being embedded in the conflicting—and often incompatible—institutional logics of social mission and commercial activities. Despite the increasing attention to such a phenomenon in the business research literature, still little is known regarding how hybrid organizational structures may facilitate or hinder the co-existence of such conflicting institutional logics. Relying on an inductive comparative case study realized on 9 socially entrepreneurial NPOs—which represent significant examples of socially imprinted organizations involved in commercial activities (hybrid)—operating in the Italian socio-healthcare sector, two main concerns have arisen as particularly influenced by organizational decisions, namely (a) effectively combining multiple identities within the organization and (b) gaining legitimacy from stakeholders. Results show that a coherent identity for a hybrid organization seems to be facilitated by an integrated structure, i.e., social programs and commercial activities run in a unique organization. On the contrary, a compartmentalized organizational structure creates two separate legal entities of a social or commercial nature only and is more crucial in gaining external legitimacy. Finally, some hybrids seem to mimic both features of these organizational structures, tackling both necessities. Thus, this study provides comparisons and practice-oriented implications to implement such organizational changes and explores the complex universe of hybrid organizational design by simultaneously comparing different organizational structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Hybrid organizations (a.k.a. Hybrids) are organizations that combine two or more of the three traditional logics (Jay, 2013; Pache & Santos, 2013) and blur the boundaries of the three traditional distinct sectors (Billis, 2010; Ebrahim et al., 2014). Traditionally, activities of for-profit organizations’ were counterbalanced by social practices from entities such as public organizations and charity organizations, which are traditionally associated with “private,” “public,” and “non-profit” sectors. However, failures of both governments and markets (Sacchetti and Borganza, 2020; Salamon, 1987; Teasdale, 2012) to address social and civil problems have led to questioning these traditional forms of organizations. Consequently, ‘hybrid organizations’ emerged as possible solutions to address citizens’ socio-economic needs and expectations (Austin et al., 2006; Dees, 1998). This new organizational arrangement provides significant economic, social, and/or environmental value for the local community and society in general (Battilana et al., 2012). In addition to organization scholars, several public management researchers are investigating the “hybrid phenomenon” to understand current changes in public services organizations, stressing the need for public organizations to develop a market orientation and for for-profit organizations to develop a socio-philanthropic attitude due to their public service utility (Billis & Rochester, 2020; Boyne & Walker, 2010; Denis et al., 2015; Joldersma & Winter, 2002; Vickers et al., 2017). Hybrid organizations do not belong to any one of the three traditional sectors completely and exclusively, so they can simultaneously cope with challenges coming from different environments. They can overcome trade-offs between three traditional conflicting logics, such as market-based principles and social welfare (Haigh et al., 2015a; Mair et al., 2015).

Many challenges exist in hybrid organizations’ management, particularly referring to sustainable solutions to maintain the organization’s original ‘social imprinting’—defined as “the founding team’s early emphasis on accomplishing the organization’s social mission” (Battilana et al., 2015, p. 1659)—while fulfilling needs of both customers and beneficiaries. Different strategic and organizational solutions have been recently emphasized to address this problem, such as ‘selective coupling’ (Pache & Santos, 2013) or ‘spaces of negotiation’ (Battilana et al., 2015). While the former solution refers to the adoption of social welfare behavior by commercially oriented organizations and market logic by charitable organizations, the latter solution allows formal arenas of interaction among the members of conflicting organizational areas (Battilana et al., 2012).

All the hybrid organizations are not social enterprises e.g., some government-originated activities could be hybrid organizations that are not operating for community welfare. It is in the social entrepreneurship realm that hybrid organizations are most common (Morales et al., 2021). Defourny and Nyssen (2017) have observed that most of the hybrid organizations still operate in the third sector. Trading charities and mutual purpose traditional social enterprises are the most common hybrid organizations. The pursuit of such a kind of organizational structure (i.e., two separate entities sharing resources and purpose) is indeed among the best solutions to simultaneously pursue beneficiaries’ welfare and economic viability (Bouchard & Rousselière, 2016). Rarer examples of hybrid organizations have been found in separate entities of for-profit businesses (to pursue CSR-related objectives) and in government-originated ventures (Defourny et al., 2021). The notion of a hybrid organization is deeply rooted in social entrepreneurship and third sector-related literature and less diffused in different streams of research (Cornelissen et al., 2021).

Despite noteworthy, published results, the literature on hybrid organizations in the context of this research (social entrepreneurship) is still limited, at least for the following three points. First, scholars have mostly identified only two alternative hybrid organizational structures to effectively design hybrid arrangements, referring to either ‘integrated’ and ‘compartmentalized’ structures (Ebrahim et al., 2014). However, the real universe of hybrid organizations is rather more complex, and there is a strong need to further explore whether other hybrid designs exist (Santos et al., 2015). Next, although the advantages and disadvantages of the integrated and compartmentalized structures have been recently explored (Haigh et al., 2015a, 2015b; Pache & Santos, 2013), an effective and simultaneous comparison of such organizational structures is missing, especially in relation to how such designs may influence critical elements for hybrid organizations management. In detail, there is the need to understand the mechanisms underlying the combination of the two identities and how it affects stakeholders’ perceived legitimacy of the organization (Zollo et al., 2019). Indeed, structural aspects, albeit fundamental, have been frequently neglected aside from a few contributions (Bouchard & Rousselière, 2016; Haigh et al., 2015b). Finally, scholars have traditionally investigated hybrid organizational arrangements focusing on for-profit companies that gradually become social enterprises (Mair et al., 2015). However, noteworthy insights might be derived from non-profit organizations (NPOs) turning into hybrid organizations, which literature refers to as the commercialization, professionalism, or managerialism of NPOs (Hwang & Powell, 2009; Kreutzer and Jäger 2009; Lee et al., 2018). Such hybrid NPOs represent significant examples of ‘socially imprinted’ organizations doing commercial activities and provide useful insights into the recent hybrid debate (Austin et al., 2006; Dees, 1998, 2012). Henceforth, how European social entrepreneurial NPOs adapt to a more US-based schema needs to be addressed. Building on these research gaps, the aim of this research is to understand how hybrid and socially entrepreneurial NPOs manage their multiple identities. We shall focus on how NPOs maintain legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders and how organizational design may play a pivotal role.

For this purpose, we selected significant Italian NPOs in the socio-healthcare sector, specifically, the Region of Tuscany emergency and urgency transportation service. Findings from an inductive comparative case study (Ridder, 2017) suggest that different organizational structures impact two main critical elements faced by hybrid organizations, namely, combining multiple identities and gaining legitimacy from internal and external stakeholders, respectively. These insights show strong managerial implications for the direct comparisons of different hybrid organizational structures in social entrepreneurship contexts.

2 Literature review

2.1 Social entrepreneurship and hybrid organizations

The hybridization phenomenon is closely related to the social entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurs, and social enterprises concepts. Social entrepreneurship has been described as an engine of innovative solutions for social problems and transformations (Dees, 1998; Pless, 2012); a virtuous behavior to achieve a social mission and recognize social value creating opportunities (Mort et al., 2003; Defourny & Nyssen, 2017).

The notion of social entrepreneurship is deeply rooted in the European non-profit and voluntary sector organizations’ research and practice traditions (Defourny & Nyssen, 2013). First, it came up in Italy and the UK, where the legislators developed an enterprise model more inclusive than traditional co-operative organizations’ model. Specifically, the aim of these two governments was to create a kind of organization that could operate in the market while simultaneously promoting social development and integration. The pertinent literature (Borzaga & Defourny, 2001; Nyssens, 2006; Defourny and Nyssens, 2012) stresses that social enterprises in Europe are characterized by an interwinding of an economic/entrepreneurial dimension (i.e., producing goods or services, economic risks, and a minimum amount of paid work), a social dimension (i.e., the aim of social benefits to the company should be launched, and be limited to profit distribution), and finally a participatory governance (i.e., a high degree of autonomy, and a decision-making system not based on capital ownership). In this regard, Defourny (2001) observed that Social Enterprises in Europe stand at cross-roads between co-operatives and NPOs. Specifically, the literature on Italian hybrid social entrepreneurial NPOs shows that these organizations grew up due to bottom-up trialing of new services by citizens and political support (Defourny & Nyssens, 2021). Anyway, it is in more recent times that they started to integrate market activities to not rely only on fundraising to survive (Karré, 2018). Consistently, governmental regulations to allow such business models followed thereafter, and the most of Italian social entrepreneurial NPOs become hybrid (Polendrini & Borgaza, 2021). In this perspective, findings from Doherty et al. (2014) review corroborated how European research considered hybrid SE as social-objectives-bound (i.e. like co-operatives, or collective-social action ventures), yet capable to distribute surpluses to better pursue the social objectives.

Complementing European literature, anyway, over the last two decades there has also been an emergence of US literature on social enterprisesParticularly referring to the non-profit context, Austin et al. (2006) defined social entrepreneurship as “the phenomenon of applying business expertise and market-based skills in the non-profit sector when non-profit organizations develop innovative approaches to earn income.” To constantly maintain financial self-sustainability (Müller & Pfleger, 2014), NPOs increasingly implement income earning activities (i.e., the “earned-income school of thought”; Eikenberry and Kluever, 2004) because of cross-sector collaborations with for-profit companies, public entities or innovative organizational structures which can integrate commercial activities (Dess ). Accordingly, the US literature posits that social enterprises are a kind of organization focused on the pursuit of social innovation through incomes derived from for-profit activities (Dees & Anderson, 2006).

In this context, the phenomenon of cross-sector partnership among three main actors such as the public (Governmental Institutions), the market (for-profit businesses) and the Third Sector (NPOs) arose in the last decades at an international level (Selsky & Parker, 2005). Hence, strategic alliances between public entities or NPOs and for-profit companies emerged and successfully impacted on local communities development (Van Tulder et al., 2016; Vestergaard et al. 2021). This created a sort of “public network” where the different sectors are more and more collaborating to effectively cope with societal, economic and environmental challenges and issues (Kenis & Provan, 2009). For instance, in recent years multiple ownership and control structures which combine different governance mechanisms (state, market, networks and self-governance) have been used in education systems and in other public sectors, (Billis & Rochester, 2020; Vakkuri & Johanson, 2020). This has given space to new hybrid arrangements that transcend the boundaries of policy domains and jurisdictions, fostering innovative forms of collaboration (Koppenjan et al., 2019; Vickers et al., 2017).

Specifically, for public policymakers and Third Sector representatives (i.e., presidents, directors, managers), this evolution represents a unique opportunity to make NPOs a strategic social actor according to a triple-bottom line (TBL) perspective: a sort of “linkage” among the public sector and the market to facilitate socio-economic development, particularly at a local/community level.

From this perspective, the notion of hybrid social enterprise emerged (Wolf & Mair, 2019). Dees (2012) refers to the hybrid structure of NPOs as social enterprises, which strive to find a sustainable balance between traditional charitable and entrepreneurial logics (Zollo et al., 2017, 2021). In this regard, it has been observed how Europe-based literature has mostly been influenced by US-based one (Mair & Marti, 2006).

In such a context, hybrid organizations represent an innovative melting pot combining two traditionally distinct models: a social welfare model that pursues its societal development mission and a revenue generation model aiming at income through commercial activities (Battilana et al., 2012; Haigh & Hoffman, 2012). As a result, managers of hybrids need to establish businesses that not only generate profit but also create societal values (Battilana et al., 2015; Pache & Santos, 2013). This empirical research is mostly rooted in the European context, as the non-profit entity is frequently the leading one and the attention of most of the hybrid organizations is towards potential beneficiaries (Tacon et al., 2017).

Managing hybrid organizations might be challenging because they combine multiple institutional logics—defined as overarching principles, values, beliefs and assumptions that prescribe what is legitimate and meaningful within different realms of an organization's social and economic life (Mongelli et al., 2017; Ramus et al., 2017)—with multiple organizational forms to sustainably cope with pressures coming from internal and external stakeholders (Jay, 2013). For these reasons, management scholars defined hybrids as ‘fragile organizations’ (Santos et al., 2015, p. 36) that risk failure (Tracey & Jarvis, 2006), breakup or ‘organizational paralysis’ due to their need of effectively balancing a social mission and fulfilling the business required by stakeholders. In this sense, literature has stressed the fact that the main challenge of hybrid organizations’ management is to have an organizational design that is able to align goals and activities that simultaneously generate profit and have a social impact (e.g., Haigh et al., 2015a, 2015b; Santos et al., 2015). Building on the above, in this paper, we specifically focus on European, namely Italian, socially entrepreneurial NPOs, which represent significant examples of socially imprinted organizations involved in commercial activities to sustain their social mission (Weerawardena et al., 2010).

2.2 Combining commercial and social activities through organizational design

The alignment between commercial goals and social activities in hybrid organizations can be pursued through the design of their organizational structures. Indeed, the organizational structure of a hybrid organization has been observed among the principal survival factors of such a kind of organization (Bouchard & Rousselière, 2016; Haigh et al., 2015b). In particular, survival has been linked to the capability to hybridize resources (Leviten-Reid, 2012). Previous studies have found that these kinds of organizations either integrate or compartmentalize their activities (Battilana et al., 2012; Ebrahim et al., 2014). The level of integration or compartmentalization is related to the social and commercial activities being carried out by the organization and thus get integrated or compartmentalized into different service sub-units, managed separately (Battilana et al., 2015; Rajala et al., 2020).

The integrated structure is a mix of activities generating social and economic value at the same time within the same entity. Strategies of this structure focus on creating a virtuous circle where for-profit activities and their revenues allow social programs to flourish and being sustainable over a reasonable period. The integrated structure is a more comprehensive approach to hybridization and a univocal decision-making process (Haigh et al., 2015a, 2015b; Mair et al., 2015; Pache & Santos, 2013). Such an element may represent one of the greatest advantages and disadvantages, at the same time to cope with pressures coming from internal and external stakeholders. Concerning the advantages, an integrated structure may (a) improve the synergic value coming from activities of a hybrid organization; (b) increase the capacity of producing outcomes for both social and for-profit activities; (c) enhance working relationships: volunteers and employees are usually more committed to the organization and feel themselves as a part of a whole (Ebrahim et al., 2014; Haigh & Hoffman, 2012). The integrated structure requires collaborations, trusted relationships, and interactions within the organization to set a collaborative and non-autocratic atmosphere (Santos et al., 2015). The disadvantage of an integrated structure is the possibility of conflicts between commercial and social logics. If the hybrid organization’s management fails to correctly integrate and manage the two logics, synergic values may not be achieved, thus creating a detrimental effect on both social-value creation and profit gaining (Battilana et al., 2012).

On the contrary, the compartmentalized structure—sometimes referred to as ‘differentiated structure’ (Ebrahim et al., 2014)—is characterized by a marked separation of the social and for-profit activities of the hybrid organization (Battilana et al., 2012). Usually, this compartmentalization translates into a formal separation of a hybrid organization into two new units—one social and the other for-profit. As a result, in the hybrid compartmentalized structure, decision-making processes, planning, stakeholder relationships and resources employed are separate. One of the advantages of this structure is the specialization of the work (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012): the social entity dedicates its energies to social programs to deliver new, more suitable and inclusive services to the community or society at large and the for-profit entity is free to structure itself, satisfying its internal needs of managerial thinking and acting. This separation may allow the organization to better cope with pressures coming from internal and external stakeholders (Ebrahim et al., 2014). Indeed, it has been observed how hybrid organizations' performances increase because of performance dialogues with stakeholders (Rajala et al., 2020). In detail, such a dialogue may allow hybrid organizations’ managers to understand how to better provide a service through the pro-profit unit while not losing touch with the social objectives. As a matter of fact, these two separate entities keep a certain level of operative and financial interdependence; in particular, the for-profit entity offers financial support to the other entity for social programs to make them sustainable (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012). One of the main disadvantages of this structure refers to a possible loss of direct control over one of the entities and consequentially an increase of conflicts (Battilana et al., 2012). For example, an original NPO may have more difficulty in understanding the strong managerial evolutions of its for-profit division. This situation may lead to the disruption of operative equilibria and a possible change of objectives for the for-profit division.

2.3 Combining multiple identities and gaining legitimacy

As already discussed above, the management of hybrids implies a continuous situation of tension due to the idiosyncratic blended nature of such organizations (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012). Managers of hybrid organizations need to cope with conflicts that may exist between internal stakeholders, who may assume different identities to gain legitimacy with relevant external stakeholders. For the purpose of this study, we rely on the definition of hybrid organization given by Albert and Whetten (1985), according to which organizational identity is the distinctive and enduring characteristics of an organization resulting from its members’ shared beliefs and meanings. According to this definition and the specific nature of hybrid organizations, which are characterized by the presence of different kinds of internal stakeholders, we can assume that in hybrid organizations, different categories of members who have different kinds of shared belief meanings may coexist. Indeed, literature on organizational identity assumes that an organization may have multiple sets of identities that are either compatible, neutral, or conflicting (Albert & Whetten, 1985). Thus, hybrid organizations may face internal tensions because of multiple organizational identities, which can lead to internal conflict (Jay, 2013). For instance, the contemporary presence of volunteers and paid employees may shape different organizational identities, causing intraorganizational tensions and conflict. Larger hybrid organizations usually employ a lot of volunteers, besides paid staff, and the conflict between volunteers and paid employees is one of the reasons for volunteers abandoning the organization (Kreutzer & Jäger, 2011). Moreover, due to their peculiar nature, hybrid organizations combine commercial and social objectives and values; this can result in recruiting employees from different directions, bringing different identities, so potentially undermining the possibility of developing a joint identity (Cornelissen et al., 2021). A strong organizational identity allows the formation of a sense of belonging and cohesion within the organization. This is essential for organizations that have a social mission because their survival is anchored on local financial support offered by the community and citizens, volunteers’ participation in activities, etc. An NPO that carries on commercial activities also, can be subjected to a process of mission drift (Eikenberry and Kluver, 2004), referring to the risks of deviating from their socially imprinted mission and related organizational identity (Battilana et al., 2015; Weerawardena et al., 2010). In this sense, managers must maintain a consistent balance between the values related to the social mission, and those related to the income-generating activities, because “commercial operations can undercut an organization’s social mission” (Dees, 1998, p.56). Due to the nature of hybrid organizations, internal stakeholders may have different awareness and comprehension about their way of being (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999), thus developing different organizational identities. Combining such identities may be problematic because of several issues; from the number of distinctive identities an organization combines to the degree of divergence or convergence between identities, thus the extent to which they are synergistic. Some organizational members could assume an identity that prevalently relies on social values, conflicting with those who assume an identity that prevalently depends on commercial values. This sort of misalignment of organizational identities may lead to direct inter-personal conflicts. For instance, an organizational identity that relies too heavily on values related to for-profit activities, which refers to risk-taking and competitive positioning, may face difficulties in blending such values with those related to non-profit activities, which stress on embeddedness, civil participation, and philanthropy. This may lead hybrid organizations to a mission drift (Eikenberry and Kluever, 2004), replacing social attitudes with competitive ones. In the realm of socially entrepreneurial NPOs, focusing on volunteers and social activities—which represent the identity and the social added value of the organization—should preserve the hybrid organization from this risk. For example, the management of hybrids should actively reassure internal stakeholders that commercial activities are not the organization’s final goal but rather an instrumental one, used only to self-finance the organization.

Yet, hybrid organizations may face legitimacy problems, in terms of acceptance by their external stakeholders, who sometimes struggle to understand and accept these new organizational forms (Battilana et al., 2015). In general, legitimacy can be meant as the outcome of a degree of congruence between the manifestations of legitimacy in an organization and the normative expectations of the external environment (Suddaby et al., 2017). Legitimacy is something that we can find in the matching between internal organizational aspects as norms, values and structures and those of the external environment. Some authors have distinguished between internal and external legitimacy (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). In particular, external legitimacy can be defined as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate with some socially constructed system of norms, beliefs and definitions” (Suchman, 1995, p. 574). Hence, external legitimacy involves continuous testing and redefinition of the acceptability and suitability of the organization through ongoing social interactions (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). In the present study, external legitimacy is considered as the perception and comprehension of an organization’s model by subjects and institutions belonging to the surrounding environment, regarded as the ‘external stakeholders’ (Rosenzweig & Singh, 1991). Due to their nature, it is difficult to categorize hybrid organizations, and for this reason, they may be penalized in accessing resources due to their complex fit with institutionalized expectations (Mair et al., 2015). Indeed, hybrid organizations must gain legitimacy from multiple audiences, both in the commercial and the social sectors. External stakeholders tend to give legitimacy according to their own perceptions about the hybrid organizations' adherence to a specific model, so evaluating different qualities of the organizations’ activities. For example, hybrids may face challenges in gaining legitimacy simultaneously from multiple sectors, assuming that the pursuit of commercial activities may cause a deviation from recognizable aspects of the social mission and vice versa (Battilana et al., 2012). An economically productive division of an NPO is more likely to be perceived as legitimate by key external market constituents such as customers or investors (Battilana et al., 2015). However, at the same time, this may cause problems related the perception of external stakeholders such as volunteers and donors who are distant from such logics. In addition, looking at the external surroundings for legitimacy, they may enter into conflict with the internal organizational identity (Mair et al., 2015).

A substantial gap of such a stream of literature comes from the fact that the organizational structure is considered as a determining condition, thus a stable context in which such problems take place, rather than integrative leverage to achieve better arrangements and solutions (Mair et al., 2015). Building on this, the research question of the present study is to investigate how different ways of organizational design may help hybrid organizations to cope with the pressures coming from internal and external stakeholders, particularly in combining multiple identities and gaining and maintaining legitimacy. Consequently, it can be formulated as: How do different organizational designs effect hybrid organization pursue of legitimacy in stakeholders’ eyes?

3 Method

3.1 Contextualization of the study

We drew our empirical evidence from the Italian social and healthcare sector. The social and healthcare sector refers to the set of services related to secondary aspects of healthcare, such as: emergency transport (ambulance) involving conditions that are life-threatening and need medical attention as fast as possible; social transport with no threat to life for situations such as dialysis appointments, diagnostic tests; other medical services such as injections, bandage or removal of stitches, post-surgery care; social and health assistance to more needy people like elderly, chronically ill, infirm, disabled, or low income (Zollo et al., 2019). These services are categorized under four main core activities: (a) ordinary social assistance toward community, (b) emergency and urgency medical services (118 service), (c) ambulatories management, and (d) funeral services (i.e., transportation of bodies, ceremony decor, and burial). Thus, the sector has strong social imprinting as it offers people-centered services, and consequences for the beneficiaries/customers are of medium/high intensity. However, players in this sector are not necessarily NPO operators, but still, the competition in several services may come, for example, from diagnosis and medical centers, private transportation companies (ambulances), agencies of social workers, and social services agencies (Sacchetti & Borganza, 2020).

In particular, the focus of the present study has been on the Region of Tuscany, where the territorial presence of NPOs in social/health sector is high and well-established. The first NPO in this sector was established in Florence in 1244, as an association of citizens for care, burial, and transportation of sick persons to lazarettos, during the pest plague. Thus, voluntarism in Tuscany is a social phenomenon that is organized, structured, and distributed in a capillary way throughout the territory for historical reasons. Its consolidation and institutional relevance can be referred to as the creation of the 118 service, the unique number for emergency (D.P.R n. 27/1992). This service is central for any NPOs operating in this sector. Compared to other regions, in Tuscany, 118 services provide transportation using ambulances and coordination of the paramedic teams are externalized for more than two-thirds of the total requirement of NPOs. The 118 is an example in which the public healthcare system exploits NPOs’ means and resources, such as provision of ambulances and volunteers, for emergency and other services. The service is organized through call centers, managed by the public healthcare system and coordinated at the regional level. The emergency calls received are evaluated for the gravity of the case, and accordingly, local units in geographical proximity directly intervene or initiate resources required to face the emergency. This led to a close relationship with regional welfare and the necessity of an orientation towards professional knowledge to be able to continue to offer 118 services. For these reasons, many NPOs also use their vocation and skills in the social and healthcare and have started to run several commercial activities to sustain their social mission (Salvini, 2012).

In this sector, NPOs and hybrid organizations are subject to quite intense competition from private and public institutions (Salvini, 2011). In addition, NPOs compete over three resources, specifically: local community involvement, local government support and normal customers, for the commercial activities. In traditional social activities, NPOs ‘fight’ over attracting volunteers, who are the lifeblood for fueling their social activities and programs. This aspect is important because if the number of volunteers reduces in a hybrid organization, it may simply reduce the level of the services or shut down certain programs; from this point of view, the Tuscan socio-healthcare system represents quite an exception. However, without the 118 services these organizations would lose their support from the government that issues refunds for the NPOs on the basis of number and type of services required by the 118. Finally, as in any business, NPOs need to offer quality services to attract clients for their commercial activities.

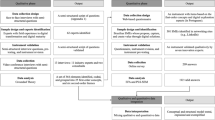

3.2 Qualitative protocol

To do an in-depth examination of different organizational replies to multiple identities' balance and legitimacy in terms of organizational design, a comparative multiple case studies approach is used (Ridder, 2017). Because our research problems are qualitative in nature (Eisenhardt, 1989) and the literature is rather limited, this methodology is suitable. We adopted multiple case studies (Yin, 1993), specifically 9 in our study, to externally validate and strengthen results coming from a single case study (within-case analysis) with a cross-case comparison (between-case analysis) (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). Such a number offered us a theoretical saturation (Eisenhardt, 1989) since the collected emergent evidence started to converge. Yet this number is in alignment or even a little above the average for a qualitative study on hybrids, e.g., Pache and Santos (2013) collected evidence from four case studies. Our qualitative research was supported by theoretical concepts related to the observed phenomena, and we consciously attempted to identify relevant examples within our data (Siggelkow, 2007). The field data provided empirical evidence, and elements of the evolving framework were revised and added regularly as the analysis moved iteratively between empirical findings and conceptual developments in a ‘reflective spiral’ (Anderson et al., 2010; Finch, 2002). This interaction of emergent theory and data collection generated our interpretative framework for the organizational design of hybrid organizations, which is presented in the next paragraph.

From a practical point of view, we selected our sample through preliminary interviews with volunteers and professionals contacted through regional charities associations, similar to what could be defined as category associations, specifically ‘ANPAS Toscana’ (the Tuscan chapter of the larger National Association of Public Assistances) for laic NPOs and ‘Confraternita delle Misericodie Toscane’ (Tuscan chapter of the larger Brotherhood of Mercy) for religion affiliated NPOs. For the criteria to include NPOs in our qualitative study, we followed the pertinent literature suggestions (Mair et al., 2015). First, we checked the availability of secondary data, such as organizations’ publications, social reports, code of ethics, publicly available statutes, and websites to allow for triangulation of data (Eisenhardt, 1989). Second, we considered the accessibility to primary data ensured by lively engagement of NPOs’ presidents and managers; this allowed researchers to have multiple rounds of feedback (Saldaña, 2012). Next, we concretely verified that organizations implement both commercial and social welfare logics and, thus, conform to the validated notion of hybrid organizations (Battilana et al., 2012; Haigh & Hoffman, 2012), which stresses the strategic importance of both types of activities. Specifically, in our study, as a proxy of this strategic focus/importance, we adopted two factors that indicate a hybrid nature of the social organization. The first factor is related to the ‘consistency’ of the commercial activities, and it was assessed through publicly available materials and confirmed by interviewees. The second parameter was the ‘stability’ of such commercial activities in the operative life of the organization. We further checked that income-generating activities were not simply limited to some sporadic events like fundraising fairs/events. Yet, according to the Italian law (n. 1460, 4/12/1997), NPOs, and hybrid organizations, cannot have commercial revenues exceeding 60% of their total volume of activities, otherwise, they lose the status of NPOs and all the fiscal and legal benefits coming from it. This threshold has been recalled in every interview as a strong limitation to the expansion. Indeed, in the case of compartmentalized hybrids, this was one of the main reasons to divide their social and for-profit activities. Thus, we can infer that the level of income-generating activities for the whole sample should be around this threshold. To summarize, our sampled organizations had high levels of income-generating activities (about 50–60% or more), and most of them were organized in a stable manner, see for example, cases of ambulatories, museums, funeral services, and retirement homes (Table 1).

Consistently with grounded theory and inductive research (Charmaz, 2008), to assure a theoretical saturation of the sampling, we selected a balanced set of Tuscan NPOs that opted either for an integrated or compartmentalized organizational design. According to Mair et al. (2015), “this sampling strategy also reflects the distribution of hybrid types in our overall sample, allowing us to substantiate mechanisms and to develop more robust insights.” According to this last parameter, we also ensured that hybrids adopting a compartmentalized structure maintain strong connections between the two entities (social and for-profit). Without this, the ‘sense’ of uniqueness and the possibility of financial and operative interdependence (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012) would collapse with the possibility to call these entities a hybrid. Such connections in our cases were represented, for example, by duality of roles in top management key roles, e.g., president of the for-profit foundation and member of the directive body in the NPO, or a contract that forces the for-profit entity to transfer a certain amount of money to the social division etc.

Through such a selection, we obtained a number of 9 cases which was deemed as appropriate, also because it represents almost half of the whole population of hybrid social entrepreneurial NPOs belonging to the metropolitan area of the Tuscany region. While the number of NPOs in this territory is larger, some of those are not relevant for the present study as they are either non-hybrid, i.e., no evident and continuous engagement with for-profit activities; or state-owned, which is a spurious situation where the organizational design may also respond to political pressures rather than for organizational needs. This metropolitan area is defined by law as the co-urbanization of three cities: Florence, Prato, and Pistoia. Being relevant for normative reasons, it also shows the highest density of NPOs in the whole region, rendering it extremely interesting to study the hybrid phenomenon. This theoretical sampling approach allowed us to create an experimental empirical basis to study the phenomenon under particularly insightful and revealing contexts (Siggelkow, 2007). The summary description of the sample NPOs is reported in Table 1 (for privacy reasons, NPOs' names have been replaced with Greek alphabetical letters).

Data collection was implemented by personal interviews with NPOs’ members who play a strategic key role within the organization—such as presidents, board members and managers. A minimum of two interviews with each interviewee were conducted for a total of 30 face-to-face interviews. The interviews were collected over a period of three years (September 2013–November 2016) and were conducted by three authors of this research paper, and one researcher attended all of them to keep an internal consistency of the protocol. Anyway, data were updated on a yearly basis through encounters with the managers to maintain them consistently. These interviews lasted anywhere between thirty minutes to two hours, they were tape-recorded and then transcribed.

Although the interview protocol during the process of data collection was ‘fluid’ to take advantage of emerging themes, following common questions were always addressed:

-

(a)

the decision-making process toward hybridization, with a focus on effects on legitimacy-related objectives (Haigh et al., 2015a, 2015b);

-

(b)

the hybrid organizations’ structure, growth, and expansion processes (Battilana et al., 2015);

-

(c)

the financial, economic and value creation aspects of the hybridization phenomenon (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012).

3.3 Coding analysis

A research diary was kept to systematically record any insight during the interviews. We began by examining all data about one single case, discarding whatever was irrelevant and bringing together what seemed most important (Eisenhardt, 1989; Saldaña, 2012). The research diaries were reviewed and constantly updated to clarify emergent themes until only a few new insights occurred. As exemplar phenomena were collected, we related them to the theoretical frame, to re-examine them in the light of these findings (Finch, 2002).

Formal interviews were transcribed, read, and re-read, with notes on emergent themes contemporaneously entered into our research diaries (Anderson et al., 2010). After the transcription of taped recorded interviews (about 300 pages), we started a manual cut-and-paste process to organize main emergent concepts, obtaining almost 50 purposeful emergent tags or codes within each case (Saldaña, 2012). These finely grained codes, not reported in the paper for brevity’s sake, represented the base for the within-case analysis. The correlated and supporting information is drawn from secondary sources—such as NPOs’ websites, statutes, and publications, e.g., an owned magazine from one NPOs ‘Il giornale di San Sebastiano’ (The Journal of San Sebastian), public press and internet contents—each member of team started the axial coding, in order to make a more aggregative iteration (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). The results of this second phase were shared among the group, and the diverse patterns obtained in isolation have been compared. To this purpose, we adopted the protocol described by Finch (2002) and applied to the entrepreneurial and management field by Anderson et al. (2010). As already generally presented in the qualitative protocol description, during the qualitative coding, we moved back and forth from the theory and the data; this operation was repeated as many times as necessary to frame all the topics in the mainstream literature. This allowed an ‘open mind’ approach for studying the data and at the same time, avoided the ‘no-where heading’ evidence, which means that our results would be completely disconnected from powerful and useful concepts and schemes drawn upon the literature (Siggelkow, 2007). Through this second step, we reduced our codes to only 17 themes (full list of these themes is reported in Table 2, divided into each category). At this point, we were ready to start the cross-case analysis to individuate common classes of issues among different realities (Eisenhardt, 1989). As the result of the coding process, 2 categories have been individuated as critical for decision about the hybrid design, namely combining multiple identities and gaining legitimacy from stakeholders.

4 Findings

Table 2 reports the results of our case study: themes of the coding analysis, overarching categories emerged, and relevant quotes from respondents. Related criticalities and suggested solutions are also included.

4.1 Hybrid organizational design

We started the analysis of our results by assessing the organizational design selected by each hybrid organization and how each structure clearly relates to different strategies used to cope with conflicting institutional logics. The NPOs in our sample structured themselves according to all types of traditional organizational designs; (1) the integrated archetype, where within the same organizational social programs and commercial activities are run simultaneously, (2) the archetype of the compartmentalized structure that instead splits a hybrid organization in two sub-entities, also legally separated, as was presented in previous paragraphs.

On the one hand, the integration strategy attempts to reconcile different competing institutional demands. Integrated NPOs of our sample internally resolved the competing institutional demands by respecting the norms imposed by the regional law—e.g., growth constraints—and simultaneously fulfilling social expectations. For these cases (Alfa and Beta), it emerged that the social division may fully benefit from financial streams coming from the for-profit division, but this, at the same time, may limit the overall growth of NPO and externally spread a perception of unfair competition. Thus, stakeholders’ expectations can only be partially satisfied. On the other hand, compartmentalization refers to strategies that apparently conform with rules and norms imposed by their institutional environment, yet operatively act in different ways. For example, the compartmentalized NPOs of our sample separated their organizational structure by creating a different entity wholly dedicated to for-profit activities. This allowed them to better conform with regional laws and norms, which prevent NPOs from having more than 60% of the total financial revenues deriving from commercial activities (as for Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, and Zeta). In this way, the for-profit entity represents an effective way to avoid growth constraints, thus respecting the legislative framework and being perceived as legitimate to ‘normally’ compete in the market arena by other stakeholders. However, this organizational design is only an apparent conformation to institutional pressures since the NPO is still able to design and control the for-profit division.

Our findings also show the adoption of a ‘selective coupling’ strategy by some hybrids (Eta, Theta, and Iota). The aim is to effectively cope with conflicting institutional logics by highlighting the hybrid’s strengths depending on the environmental context in which the activities are carried out; and situation that could please both internal and external stakeholders’ requirements (Alexius & Grossi, 2018). Because of this, for-profit entities are exploited as strategic vehicles to implement activities in new fields and markets. Specifically, our results show how some hybrids decided to adopt what we can refer to as ‘a mixed organizational design’ where the main hybrid organization—which we will refer as the ‘mother organization’—has a hybrid nature, implementing both social and for-profit activities within a unique entity, as in the traditional integrated structure. However, they also create ‘satellite entities’ which are separate and autonomous from the ‘mother,’ and they implement specific for-profit activities in a more efficient and effective way than a hybrid could do. In this way, the mother organization exploits these entities to carry out commercial activities in different geographical areas separate from traditional regions, usually even using a different name, to increase the autonomy. Differently from the compartmentalized structure, these hybrids let their satellites operate in geographical areas which could not otherwise be reachable or in commercial activities particularly ‘distant’ from the cultural background of the mother organization. This way of organizational designing may allow hybrid organizations to mimic and render more evident features of a commercial nature according to actual contingencies to stimulate/preserve legitimacy of the satellites. Likewise, the ‘mother’ organization remains an integrated hybrid—carrying out its ‘core’ and traditional social and commercial activities—thus mitigating risks of coping with multiple identities, especially distant logics from its background, and preserving support of internal stakeholders.

The three organizational responses and strategies are summarized in Fig. 1.

In the following sub-paragraphs, we will present the two critical elements that emerge from the analysis, combining multiple identities and gaining legitimacy and situational advantages/disadvantages within each type of hybrid organizational structure. From in-depth interviews of managers and board members of the selected NPOs, we find that each of these factors may be improved or hindered by different organizational designs.

4.2 Combining multiple identities

The first category of critical elements emerged from our sample NPOs refers to combining multiple identities, namely the social and commercial ones. Two of the NPOs of our sample showed the features of an integrated hybrid structure, namely Alfa and Beta. As reported in Table 2, Alfa and Beta NPOs that adopted an integrated hybrid structure, while recognizing the management of organizational identities as a critical factor for survival also showed no particular high pressures coming from this aspect. Managing their organizational identity, referring to the difficulty of combining two traditionally opposite institutional logics, such as social mission and commercial activities within the same organization, seems not a problem in the current situation. The management of this hybrid combines multiple organizational identities being transparent and clear toward its internal stakeholders, the volunteers and employees, particularly stressing the need of deploying commercial revenues to be financially self-sustainable. From interviews, it clearly emerges that a decision to compartmentalize an NPO would be interpreted as a way of ‘exploiting’ the voluntary association for commercial and for-profit interests, as in the words of the director of Alpha. Similarly, the President of Beta stated that financial revenues are used to better pay their own volunteers. In this case, the ability of the management was to successfully create an internal shared culture about the use and deployment of commercial activities. Again, management’s transparency toward internal stakeholders about the nature and the scope of for-profit activities has been crucial for volunteers’ approval. In both cases, management’s ability to communicate with internal stakeholders, explaining reasons for choosing a specific hybrid organizational structure and clearly explaining its functioning and objectives has paid off.

Oppositely, four hybrids showed the features of a compartmentalized structure—Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, and Zeta. They show high levels of pressure referring to the management of the organizational identity. The main problems refer to the nature of the for-profit division created to carry out the commercial activities, which is usually difficult to combine with the identity of the original hybrid. Gamma created an ad hoc foundation that manages funeral services and ambulatories management and a promotional agency. Particularly for the second entity, a Ltd. company has been co-created in a consortium, which caused identity issues because volunteers interpreted such an alliance as purely commercially driven agreement and did not fully accept a collaboration with other organizations characterized by historically different values and cultures. Similarly, Epsilon had several problems in combining multiple identities mainly due to the object difficulty of managing different legal entities, which carry out commercial services, e.g., ambulatories management, funeral services, and bar activities. Indeed, volunteers at the beginning raised concerns toward commercial activities, fearing a possible mission drift and loss of identity for the for-profit division. To cope with similar problems, Delta decided to (a) name the for-profit division in the same way as the NPO; (b) cautiously separated volunteers from employees in the two entities, to avoid blending different approaches and logic in the operation of the hybrid; (c) clearly stressed the need to generate financial revenues with the separate entity, which is much more efficient and provide financial sustainability to the NPO. Thus, the original social division can provide more social services. The President of Zeta also confirmed that maintaining a univocal organizational identity in a compartmentalized hybrid structure represents one of the main challenges for the NPO. The only remedy found by this hybrid has been to effectively stress the efficiency of a separate for-profit division in creating sustainable streams of revenues. Yet, internal stakeholders have been repeatedly reassured about the ultimate social objective of the for-profit entity, in terms of self-financing the NPO, and, in some cases, providing a salary to disadvantaged people employed in the for-profit division, thus, finally reconciling the commercial division to a social inclusion issue.

Finally, the three hybrids—Eta, Theta, and Iota –showed what we defined as a mixed organizational structure. Combining multiple identities is a prominent critical element. However, their structure seems to respond quite efficiently. In this way, a reciprocal relationship of trust (Göbel et al., 2013) was created between the mother organization and its satellites. In the case of Theta, for example, the management leaves its satellites quite independent, with only key roles of the governance body being the same as the NPO’s mother organization. They aim to maintain a sustainable common vision and common long-term objectives, but at the same time, a rigid separation of operative roles. Moreover, the management paid a lot of attention in emphasizing the high professionalism and competence for the satellites’ employees. This made volunteers aware of the differences between the two ‘entities’ from other more traditional for-profit activities that are kept in the integrated mother organization. As reported by the director of Iota, the satellites’ activities are carried out in a different Italian region than the mother organization. Also, in this case, it is impossible to manage such services internally by the mother organization, thereby enabling the acceptance of some specific for-profit divisions from internal stakeholders.

4.3 Gaining legitimacy

Results from the case study showed how gaining legitimacy from external stakeholders represented the category of elements essential to the survival and growth of the NPOs. For the two NPOs with an integrated structure, this element creates strong problems. As stated by the Director of Alpha, the management decided to remain integrated because the creation of a for-profit entity would hinder volunteers’ perception of the NPO. Indeed, the management perceived that the legitimacy gained in more than one hundred years of continuous operations may be reduced by creation of for-profit entities (Manetti et al., 2017). Similarly, Beta experienced problems in gaining legitimacy from competitors. To cope with such an issue, the President refers that a large amount of time and resources were spent to institutionally communicate clearly to a plethora of stakeholders (e.g., governmental agencies, competitors of the for-profit activities in the local area, and the community at large), and all the commercial activities were carried out by volunteers—and not employees—and all the financial revenues were re-invested in the NPO. This helped in gaining acceptance from for-profit organizations carrying out similar commercial activities—such as funeral services and ambulatories management—but this remains a delicate issue to be resolved. As a result, it emerged that integrated hybrids usually give preference to maintaining high levels of multiple identities combination by prioritizing internal stakeholders’ expectations—above all volunteers and beneficiaries—and attempting to enhance the perceived legitimacy of their environment.

Instead, the empirical analysis showed how the four compartmentalized hybrids successfully gained high levels of acceptability after the creation of the for-profit entity, as reported by the President of Gamma, who is also a member of the board of the for-profit foundation. Interestingly, the interviews with Epsilon showed that external stakeholders—such as customers and competitors—did not perceive the NPOs’ for-profit entities as ‘real competitors of other for-profit organizations, mainly because all the financial revenues are utilized for the NPO’s growth and self-sustainability. Similarly, the Director of Zeta also confirmed this aspect. Finally, the Director of Delta stated that their for-profit entity benefitted from the ‘Association brand’—referring to the values, culture, and identity historically associated to their NPO’s name within the regional area—to gain legitimacy from external stakeholders. Also, in this case, the surrounding community did not perceive the for-profit entity as an unfair competitor mainly because the management has clearly and transparently stressed that all the revenues are re-invested in the NPO, contributing to its expansion. As a result, gaining legitimacy for the analyzed compartmentalized hybrids was favored from the creation of a separate for-profit entity. Hence, the history of the organization does not represent a burden in the case. It may be helpful to communicate the intention to invest the revenues of the for-profit entity in the no-profit one (Testi et al., 2017). In particular, it emerged how communication about the history is relevant when there is the need to explain the for-profit entity as necessary for the continuance of the whole organization.

The three hybrids using the mixed organizational structure, or the ‘mother-satellites’ structure, gaining legitimacy was facilitated by the adoption of satellites, similarly to what happens in the compartmentalized structure. This was stressed by the President and the Director of Iota, who confirmed that the ‘mother’ NPO benefitted a lot in terms of legitimacy after the creation of the satellites. Particularly, the perceived incompatibility between competing institutional logics was reduced due to an effective balance of social and commercial orientation carried out by the ‘mother’ NPO and satellites, respectively. Concerning Eta, initially, this hybrid opted for an integrated organizational structure, thus, integrating both social and commercial activities within the same organization. Both external stakeholders did not perceive the commercial services as legitimate, hence, the management decided to create external and autonomous for-profit entities under a different name to clearly separate the two competing logics. In all these cases, the selective coupling strategy was successfully enacted, but this required a lot of effort in terms of clear and transparent communication to stakeholders about the use of revenues for the whole hybrid’s financial self-sustainability.

A summary of insights that emerged from our case studies is summarized in Table 3.

The interpretative framework from our studies is presented in Fig. 2 to illustrate our strategic guidelines and organizational design suggestions for hybrids’ managers and practitioners. In the following section, we discuss the framework for main implications according to a strategic and organizational perspective.

5 Discussion

Our study seeks a better understanding of hybrids’ response to crucial elements affecting their survival, growth and, thus, ultimately, their organizational effectiveness. Specifically, it focuses on the way hybrids cope with combining multiple identities and gaining legitimacy from external stakeholders. Consistent with the pertinent literature (Battilana et al., 2012; Mair et al., 2015), our case study establishes how hybrids need to constantly face competing institutional demands—such as social and commercial expectations—by adopting two main organizational design responses (Battilana et al., 2015). The first type of response is prevalently adopted by integrated hybrids, as seen from our empirical results. These are more inclined to satisfy internal stakeholders’ expectations of effectively combining the organization’s multiple identities. Precisely, volunteers, members and employees of the integrated hybrids require high levels of transparency and communication to clearly understand the ultimate objective pursued by the commercial division—which is to re-invest the financial revenues to become self-sustainable and fulfill the social division needs. In this sense, some authors (Jäger & Schröer, 2014) have proposed the concept of ‘integrated identity’ to overcome the concept of ‘multiple or dual organizational identity’; given the possible strong tensions between the social and the commercial component of hybrid organizational identity, and between the paid employees and the volunteers’ cultures and values, this integration is not easy, but the integrated organizational model can be an effective answer to such tensions. However, at the same time, external stakeholders may perceive integrated hybrids as ‘unfair’ competitors because of their fiscal benefits, advantages they derive from their legal status, and their inability to attract a ‘zero-cost’ labor force, i.e., volunteers performing tasks for the for-profit division. In this sense, the ‘integration’ strategy attempts to enact within the same integrated organization compatible normative and behavioral processes to gain a minimum standard of external stakeholders’ expectations while succeeding in combining multiple identities (Pache & Santos, 2013). For these reasons, we summarize the following:

Proposition 1a

An integrated organizational structure emphasizes the relevance of internal stakeholders allowing hybrid organizations to obtain high levels of efficiency in managing multiple organizational identities.

Proposition 1b

An integrated organizational structure allows hybrid organizations to obtain only minimum levels of efficiency in gaining external legitimacy.

On the contrary, the second type of organizational design response is more frequently adopted by compartmentalized hybrids. These hybrids aim to expand their commercial activities through a separate for-profit division, usually perceived as much legitimated by institutional stakeholders—such as competitors and the local government. Indeed, the creation of a ‘pure’ for-profit division allows the hybrid to compete with the existing for-profit competitors equally and fairly, without any sort of growth constraints or legal limitations due to the status of NPO. However, the most delicate issue for such a solution refers to a possible loss of identity, precisely a mission drift from the original ‘social imprinting’ of the NPO (Battilana et al., 2015). Consequently, NPOs’ management should appropriately maintain the original values and cultural aspects in the for-profit entity, clearly emphasizing the need to generate financial revenues for an overall improvement of the organization itself. In this case, it emerged that shared governance between the social and commercial divisions is one of the best solutions for coping with multiple identities’ issues. Thus, we propose the following:

Proposition 2a

A compartmentalized organizational structure emphasizes the relevance of external stakeholders allowing to obtain high levels of efficiency in gaining legitimacy.

Proposition 2b

A compartmentalized organizational structure allows hybrid organizations to obtain only minimum levels of efficiency in managing multiple organizational identities

The mixed organizational structure, or the ‘mother-satellites’ structure, assumes the strategy of the ‘selective coupling’ (Pache & Santos, 2013), allowing the hybrids to be purely commercial in distant and far-reaching areas, while simultaneously remaining integrated in the territorial area. In this way, advantages of both the integrated and compartmentalized solutions may be achieved. This structure shows an effective organizational response to simultaneously face both hybrids’ critical elements, namely combining multiple identities and gaining legitimacy. Actually, from our case studies, it emerged that three hybrids adopting such a strategy show the most adequate and ‘fitting’ organizational nature depending on the institutional context—social or commercial—mainly to meet both internal and external stakeholders’ expectations. However, pursuing both types of expectations simultaneously may impede a complete fulfillment of each of them. Thus, the ‘pure’ organizational structures may result in a higher level of satisfaction of internal and external stakeholders’ expectations for the compartmentalized structure. Consequentially, we propose the following:

Proposition 3

A mixed organizational structure emphasizes the relevance of both internal and external stakeholders allowing to obtain medium-high levels of efficiency in managing multiple organizational identities and gaining legitimacy.

Hence, the best organizational response for a hybrid depends on which stakeholder’s expectation assumes the highest priority, thus stressing the crucial role played by both internal and external stakeholders in the sustainability of hybrid organizations. Therefore, our propositions and interpretive framework would indicate to the management of hybrids that they should adopt one of the two organizational responses depending on which stakeholder’s expectation they aim to satisfy the most. Specifically, our findings suggest that (see Fig. 2): (1) an integrated structure is a suitable organizational configuration when there is a strong emphasis on managing multiple identities and the management can afford lower levels of external legitimacy; (2) a compartmentalized structure instead responds well in increasing the legitimacy, but at the expenses of previous equilibria in managing multiple identities; and (3) a mixed structure or the ‘mother-satellites’ structure seems to better response when it is necessary to maintain simultaneously the equilibrium between managing multiple identities and gaining external legitimacy.

6 Conclusions

As we already described in our discussion section, based on our multiple studies, we have shed more light on how critical elements of the management of a hybrid organization can be faced. Actually, both scholars and practitioners recently stressed the importance of improving the way NPOs are managed in a more structured fashion, especially in the European context (Zollo et al., 2021). NPOs—as well as organizations belonging to the Third Sector in general—frequently “mix” commercial and philanthropic activities in an unstructured and even non-institutionalized way, thus giving rise to several critical issues concerning organizational identity (principles, values, beliefs, etc.) and image (the way the organization is perceived from outside) (Battilana et al., 2015; Dees, 2012; Pache & Santos, 2013). As a result, hybrids’ economic and social performances suffer due to misalignment between their mission/vision and organizational settings. One of the main goals of the present research was to highlight the need for NPOs, using hybrid organizational arrangements, to follow structured and clear frameworks Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). To accomplish their objectives in a more effective way and to fulfill their social and economic goals, at the same time, they should choose the proper organizational design, setting and response. In addition to the economic advantages, we believe that a better organizational structuring and response to hybrid challenges might positively impact on NPOs’ environmental and institutional legitimacy, which is a significant element for their long-term survival (Zollo et al., 2019).

Our contribution to the literature is, at least, twofold; firstly, our study increased the understanding of the real universe of hybrids’ organizational arrangements beyond the traditional ‘integrated’ and ‘compartmentalized’ organizational structures (Battilana et al., 2012; Ebrahim et al., 2014). Indeed, our study confirms that hybrids tend to use satellites to cope better with the pressures of their institutional environment (Pache & Santos, 2013; Santos et al., 2015). Secondly, we clearly compared how a major focus on managing multiple identities and/or on gaining legitimacy may affect the organizational design (Haigh et al., 2015a, 2015b). A study that effectively and simultaneously compares such organizational structures was missing, especially in relation to how such designs may influence critical elements of hybrid organizations. Finally, our study is particularly interesting because we investigated NPOs that turned into hybrid organizations that have received limited attention from the academic community (Dees, 2012).

However, like every case study research, the findings of our study suffer from generalizability to a larger population since it is based only on a specific territorial setting—the Tuscan Region in Italy, and only on one type of hybrids—those involved in the social-healthcare sector. To overcome these limitations, it is necessary to carry out investigations about the organizational responses for hybrids in other regional and institutional contexts, considering whether and how the three strategies are functioning. However, we believe that our study contributes to the growing body of literature of hybrid organizations; following pertinent literature (Battilana et al., 2015; Haigh et al., 2015a, 2015b; Pache & Santos, 2013), we actually focused on the way hybrids’ management cope with existing conflicting logics, and not on their specific content (Santos et al., 2015). Indeed, these are general concerns shared by all hybrid organizations. In terms of future research, we believe that selective coupling and a coherent mixed organizational structure is an interesting strategic solution, that should be studied further since it offers intermediate levels of efficiency to manage organizational identity and legitimacy issues at the same time. For example, it is necessary to determine an ‘efficiency barrier,’ or in other words, determining points where one of three structures become more efficient than the others (dotted line of Fig. 2). Thus, it would be important to study, both at theoretical and empirical levels, the thresholds for which the attention to internal or/and external stakeholders becomes so critical to require a shift of organizational design. Specifically, we can offer a set of research questions worthwhile to further studies. In relation to our first and second propositions, it can be further inquired: How the relevance of the internal (or external) stakeholders can be gauged? What is or How to determine the threshold of relevance that justifies the adoption of an integrated (or compartmentalized) structure?

Finally, our third proposition postulates a possible balance between managing identities and gaining legitimacy and thus a balance between internal and external stakeholders’ expectations. However, this mixed structure can be considered as a compromise of the other two and is necessary to individuate its ‘range of efficient application.’ Thus: What are and how to determine intermediate levels of relevance that justify the adoption of a mixed structure?

In relation to this, we believe that more evidence on the hybrids’ use of satellites would be beneficial to the stream of literature.

References

Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 7, pp. 263–295). JAI Press.

Alexius, S., & Grossi, G. (2018). Decoupling in the age of market-embedded morality: Responsible gambling in a hybrid organization. Journal of Management and Governance, 22(2), 285–313.

Anderson, A. R., Dodd, S. D., & Jack, S. (2010). Network practices and entrepreneurial growth. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26(2), 121–133.

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 1–22.

Battilana, J., Lee, M., Walker, J., & Dorsey, C. (2012). In search of the hybrid ideal. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 10(3), 51–55.

Battilana, J., Sengul, M., Pache, A. C., & Model, J. (2015). Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: The case of work integration social enterprises. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1658–1685.

Billis, D. (2010). Hybrid organizations and the third sector: Challenges for practice, theory and policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Billis, D., & Rochester, C. (Eds.). (2020). Handbook on hybrid organisations. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Borzaga, C., & Defourny, J. (2001). The emergence of social enterprise. Routledge.

Bouchard, M.J., & Rousselière, D. (2016). Do hybrid organizational forms of the social economy have a greater chance of surviving? An examination of the case of Montreal. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(4), 1894–1922.

Boyne, G. A., & Walker, R. M. (2010). Strategic management and public service performance: The way ahead. Public Administration Review, 70, 185–192.

Charmaz, K. (2008). Grounded theory as an emergent method. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & P. Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp. 155–170). Guilford Press.

Cornelissen, J. P., Akemu, O., Jonkman, J. G., & Werner, M. D. (2021). Building character: The formation of a hybrid organizational identity in a social enterprise. Journal of Management Studies, 58(5), 1294–1330.

Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits. Harvard Business Review, 76, 54–69.

Dees, J. G. (2012). A tale of two cultures: Charity, problem solving, and the future of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 321–334.

Dees, J. G., & Anderson, B. B. (2006). Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: Building on two schools of practice and thought. Research on Social Enterpreneurship, 1(3), 39–66.

Defourny, J. (2001). From third sector to social enterprise. In C. Borzaga & J. Defourny (Eds.), The emergence of social enterprise 2 (pp. 1–28). Routledge.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2012). Conceptions of social enterprise in Europe: A comparative perspective with the United States. In J. Defourny, & M., Nyssens, Social enterprises (pp. 71–90). London (UK), Palgrave Macmillan.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2013). Social co-operatives: When social enterprises meet the co-operative tradition. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity, 2(2), 11–33.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2017). Fundamentals for an international typology of social enterprise models. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(6), 2469–2497.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2021). Social enterprise, welfare regimes and policy implications. In J. Defourny, & M., Nyssens, Social enterprise in Western Europe: Theory, Models and Practice (pp.351–356). London (UK), Routledge.

Defourny, J., Nyssens, M., & Brolis, O. (2021). Testing social enterprise models across the world: Evidence from the “International Comparative Social Enterprise Models (ICSEM) project.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(2), 420–440.

Denis, J. L., Ferlie, E., & Van Gestel, N. (2015). Understanding hybridity in public organizations. Public Administration, 93(2), 273–289.

Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436.

Ebrahim, A., Battilana, J., & Mair, J. (2014). The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, 81–100.

Eikenberry, A. M., & Drapal Kluver, J. (2004). The marketization of the nonprofit sector: Civil society at risk? Public Administration Review, 64(2), 132–140.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

Finch, J. (2002). The role of grounded theory in developing economic theory. Journal of Economic Methodology, 9(2), 213–234.

Göbel, M., Vogel, R., & Weber, C. (2013). Management research on reciprocity: A review of the literature. Business Research, 6(1), 34–53.

Haigh, N., & Hoffman, A. (2012). Hybrid organizations: The next chapter of sustainable business. Organizational Dynamics, 41(2), 126–134.

Haigh, N., Kennedy, E. D., & Walker, J. (2015a). Hybrid organizations as shape-shifters. California Management Review, 57(3), 59–82.

Haigh, N., Walker, J., Bacq, S., & Kickul, J. (2015b). Hybrid organizations: Origins, strategies, impacts, and implications. California Management Review, 57(3), 5–12.

Hwang, H., & Powell, W. W. (2009). The rationalization of charity: The influences of professionalism in the nonprofit sector. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(2), 268–298.

Jäger, U.P., & Schröer, A. (2014). Integrated organizational identity: A definition of hybrid organizations and a research agenda. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25(5), 1281–1306.

Jay, J. (2013). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137–159.

Joldersma, C., & Winter, V. (2002). Strategic management in hybrid organizations. Public Management Review, 4(1), 83–99.

Karré, P. M. (2018). Navigating between opportunities and risks: The effects of hybridity for social enterprises engaged in social innovation. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity, 7(1), 37–60.

Kenis, P., & Provan, K. G. (2009). Towards an exogenous theory of public network performance. Public Administration, 87(3), 440–456.

Koppenjan, J., Karré, P. M., & d Termeer, K. (Eds.). (2019). Smart hybridity: Potentials and challenges of new governance arrangements. Eleven International Publishing.

Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 64–81.