Abstract

We present an improved methodology for a thermal transient method enabling simultaneous measurement of thermal conductivity and specific heat of nanoscale structures with one-dimensional heat flow. The temporal response of a sample to finite duration heat pulse inputs for both short (1 ns) and long (5 μs) pulses is analyzed and exploited to deduce the thermal properties. Excellent agreement has been obtained between the recovered physical parameters and computational simulations through choosing an optimized pulse width.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

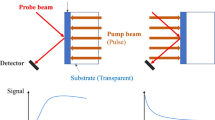

Accurate thermal characterization of low-dimensional structures is necessary both for fundamental understanding of heat transport at the nano-/macro-scale and for practical purposes such as determining the figure of merit of thermoelectric materials. However, the steady-state methods typically employed suffer from difficulties with thermal gradients and also require separate experiments to determine individual values of thermal conductivity (k), specific heat (C), and thermal diffusivity (D). Transient techniques can be exploited to circumvent the above difficulties [1, 2]. An early experiment in this regard entailed monitoring heat pulse propagation at a particular location on the sample and computation of the statistical moments of the temperature (T) versus time (t) curve to determine k and C [3]. In this case, the dispersion of a heat pulse as it travels down a sample as shown schematically in Fig. 1 can be quantified through the computation of its moments and related to the thermal parameters appearing in the solution of the corresponding heat equation (obtained through Laplace transform techniques). The moments, f n , have been defined as [4]

where ΔT(x,t) is the measured temperature change as a function of time (t) at a point (x) along the sample in response to a heat pulse, and n refers to the order of the moment. Through a differentiation theorem [5], it can be shown that these moments can also be expanded in terms of the Laplace transform of the temperature profile, ΔT(x,s), through

where s is the complex variable introduced in the Laplace transform. In Eq. 2, ΔT(x,s) can be taken to be the Laplace transform of the solution for the heat conduction equation. The moments method then relates the time-weighted integrals of ΔT(x,t) to derivatives of ΔT(x,s) through Eq. 2 to allow k and C to be extracted, and has the advantage that it can be modified to account for the influence of auxiliary thermal sources and sinks (i.e. heaters, thermometers, substrate/supporting structures, etc.) [6–8].

While the above formulation in its original form using δ-function like pulses is adaptable for nanoscale structures with one-dimensional heat flow, its application has been hindered by the fact that large geometric aspect ratios (inherent to nanotubes, nanowires, and thin films) and small energies (fJ–pJ) yield temperature changes (ΔT) that are very difficult to measure. Larger temperature changes through resistive heating can be achieved by increasing the heater power. However a heater cross-sectional area large enough to avoid electromigration [9] can also lead to undesirable thermal parasitics that complicate analyses. Alternately, increasing the applied current duration can cause deviations in the experimental temperature profiles resulting in substantial errors in the computation of the moments. In this letter, we reconsider the form of the input energy for a nanowire (assuming a rectangular cross-sectional area) to provide a new experimental formulation for k and C, and then demonstrate the recovery of these thermal parameters through simulations and improved computational methods.

We assume a one-dimensional heat conduction equation approximation which is valid when the sample is taken to be a wire with a very large aspect ratio (e.g. nanowire) with the appropriate boundary conditions. The heat pulse and heat sink are applied uniformly across the ends of the wire inducing isothermal cross sections normal to the wire axis. Therefore, the heat conduction along an isolated square wire (Fig. 1) of cross-sectional area A (=wh) and length l, where l ≫ w, h, is described by

where R′ = 1/kA is the thermal resistivity and C′ = CρA is the specific heat (both per unit length) and ρ is the density of the wire material. We then apply the following boundary and initial conditions at ambient temperature T 0:

where P 0 is the input power magnitude, u(t) is a unit step function, and P(x = 0,t) defines a heat pulse of duration τ with total energy Q = P 0τ. Consideration of very small durations (τ → 0) will lead to the original pulse-based moments method [10–12], while a long duration pulse (τ → ∞) would imply steady-state heat conduction. In the following, we work with finite duration input pulses, resulting in responses exhibiting both transient and steady-state attributes and enabling the determination of both k and C from a single experimental measurement.

The problem is modeled as a thermal analog to the electrical transmission line problem and its solution determined using Laplace transform techniques. For the specified boundary and initial conditions, we have derived the change in temperature along the wire, for a given cross-sectional area, to be

The moments are then evaluated using Eq. 2 from the solution of an equivalent transmission line model for the wire, given by Eq. 7, and related to a known temperature profile, ΔT(x,t), through Eq. 1. At least two of the moments must be calculated for determining the two desired thermal parameters, k and C. For n = 0, 1 and 2, we find that

If ΔT(x,t) is determined experimentally, Eqs. 8–10 can be evaluated in units of [Ks], [Ks 2], and [Ks 3], respectively, and k and C can be explicitly solved.

To demonstrate that the use of heat pulses of finite pulse duration is sufficient to recover k and C from the experimentally determined T vs. t profiles, we simulated heat transfer along a Si nanowire using COMSOL Multiphysics® for several different types of heat inputs as shown in Fig. 2. The materials constants for a Si nanowire (i.e. 20 nm × 20 nm × 3 μm) were taken to be as follows: thermal conductivity k = 7 W m−1 K−1 (at T 0 = 300 K) [13], density ρ = 2,329 kg m−3 and specific heat C = 702 J kg−1 K−1 [14]. The initial temperature (T 0), set to 300 K, corresponds to a wire initially in equilibrium and in contact with a large thermal bath. An experiment in high vacuum (<10−6 Torr) and at 300 K would imply thermal conduction to be the dominant heat transfer mechanism over convective and radiative effects, which have consequently been ignored.

a Short duration/high power (1 ns, 1 μW, dashed line), long duration/low power (10 μs, 100 pW, dotted line), and time optimized (5 μs, 200 pW, solid line) heat pulses responses, all at x = 1.5 μm (= l/2) with Q = 1 fJ. b Time- and amplitude-optimized response from a 100 fJ (5 μs, 20 nW) heat pulse. The plots have been time-shifted (by ~12 ns in a, and ~18 ns in b) to omit the delay required for the excited heat wave to travel to x = l/2

Figure 2a shows the temperature response in the nanowire at the halfway point (x = 1.5 μm) due to three different pulse inputs, all having total energy of 1 fJ:1 μW for 1 ns (dashed), 100 pW for 10 μs (dotted), and 200 pW for 5 μs (solid). The 1 ns pulse, which excites a purely transient response, corresponds to the δ-function-like pulses implicit in previous moment based methods. While the maximum temperature deviation of this profile is the largest of the three inputs (~0.5 K), it occurs very early (~400 ns) and has substantially decayed after several microseconds. In contrast, the 10 μs pulse introduces a more gradual heating that drives the nanowire into steady-state (for ~7 μs), allowing a significantly wider time response, but produces a lower maximum temperature excursion (~50 mK). Temperature responses that have sub-Kelvin temperature changes and sub-μs transient features impose a variety of experimental challenges such as the need for amplification hardware with extremely high speed sampling and resolution, along with rapid settling times. However, for a given pulse energy we observed through numerical simulations that such challenges could be overcome by applying an input with an optimized pulse width (t opt) that just achieves the onset of steady-state temperature through the wire, e.g., using a 1 fJ pulse with a 5 μs duration. Increasing the pulse energy for the optimized duration further increases the amplitude of the temperature response. Figure 2b shows the response of the 5 μs pulse with increased total energy (100 fJ) with a temperature increment of ~10 K, which can now be easily measured. An approximate time scale for the t opt may also be obtained through a lumped thermal capacity model for the wire through

For the assumed parameters, we obtain a t opt ~ 2 μs, which is quite close to the value (~5 μs) determined from simulation.

Previous work using the moments method fit the T vs. t transient response with combinations of exponential functions [7, 8]. Generally, analytical curve fitting of rapidly varying signals requires piecewise fits and produces discontinuities, leading to inaccurate computation of numerical integrals. In our analysis, we have avoided such kind of curve fits, and instead weight the simulated temperature curve, ΔT(x,t), by t n to generate the integrands of Eq. 1, for n = 0, 1, and 2. MATLAB software was used to generate and numerically integrate linear-interpolation curve fits to yield f 0, f 1, and f 2. Equations 8–10 are then solved simultaneously to determine k and C. The values from the three possible combinations of chosen f n , for the 1 ns (Fig. 2a, dashed curve) and 5 μs (Fig. 2b) pulses, are represented in Table 1.

The values for k recovered from our moments analyses match very well (e.g. 2.7% for C constitutes the maximum deviation) with the input parameters to within the reported significant figures. The sources of error are primarily artifacts inherent in finite element modeling, specifically: (1) finite geometrical mesh elements and, (2) finite iteration time stepping. Both sources create discretization errors over the entire T vs. t profile, which are further exacerbated when utilizing rapidly varying transient signals or computing higher order moments. For example, the deviations of the recovered specific heat are larger for the 1 ns pulse compared to the 5 μs pulse, as shown in Table 1. Furthermore, for the 1 ns pulse, the error from the recovered specific heat for higher order moments (2.7% for f 1 and f 2) is larger than that from the lower order moments (<1% for f 0 and f 1). We think that further refinement of the simulations to eliminate the above error sources is unnecessary because of their insignificance compared to intrinsic electrical noise in real experiments [6, 7].

A suspended nanowire similar to those previously used [15–17] can be used to demonstrate our proposed method. The nanowire would be suspended across a heating and sensing membrane to provide control of the thermal boundary conditions through: (1) Joule heating of resistive micro-heaters located near the ends of the sample, (2) thermal isolation along the length of the sample when performing the measurement in vacuum. While resting a sample across the heating and sensing membranes will impose a thermal boundary condition perpendicular to the sample axis at the points of contact, the one-dimensional approximation is still appropriate if the length (l) of the wire is significantly larger than the width/height [6]. We are currently fabricating such a suspended micro-device to provide experimental proof of principle.

Our proposed method should be generally adaptable for one-dimensional nanostructures with lengths where t opt is not too short or too long—the former would impose severe limitations on the temperature large times would enable parasitic heat transport. Other limitations of the approach involve the auxiliary effects of the electrodes and measurement apparatus which could be reduced through choosing an appropriate t opt. In conclusion, our proposed modification, through the use of finite duration heat pulses and improved computational procedure, makes more practicable the original formulation of thermal transient methods, for the determination of thermal conductivity and specific heat of nanostructures with one-dimensional heat flow.

References

Carslaw HS, Jaeger JC. Conduction of heat in solids. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1959.

Bertman B, Heberlein DC, Sandiford DJ, Shen L, Wagner RR. Diffusive temperature pulses in solids. Cryogenics. 1970;10(4):326–7.

Gershenson M, Alterovitz S. A mathematical method for the analysis of heat capacity and thermal conductivity measurements by the heat pulse technique. Appl Phys A. 1975;5(4):329–34.

Alterovitz S, Gershenson M. A moments method applied to laplace transform technique for experimental physics. J Comput Phys. 1975;19(2):121–33.

Doetsch G. Guide to the application of the Laplace and z-transforms, vol. 2. London: Van Nostrand; 1971.

Shapira Y, Alterovitz S. Application of a moments method and of laplace transforms to heat transfer experiments. J Therm Anal. 1980;18(3):477–91.

Alterovitz S, Deutscher G, Gershenson M. Heat capacity and thermal conductivity of sintered Al2O3 at low temperatures by the heat pulse technique. J Appl Phys. 1975;46(8):3637–43.

Bortner LJ, Newrock RS, Resnick DJ. An analysis of the heat pulse method for thermal transport measurements of thin films. J Appl Phys. 1987;61(9):4452–7.

Ghate PB. Electromigration-induced failures in VLSI interconnects. In: Proceedings of the 20th annual reliability physics symposium. New York: IEEE Press; 1982. p. 292–9

Filler RL, Lindenfeld P, Deutscher G. Specific heat and thermal conductivity measurements on thin films with a pulse method. Rev Sci Instrum. 1975;46(4):439–42.

Cruz-Uribe A, Trefny JU. The thermal properties of thin films at low temperatures using an improved heat-pulse method. J Phys E: Sci Instrum. 1982;15(10):1054–9.

Madsen J, Trefny JU. Boundary effects in transient thermal measurements. J Phys E: Sci Instrum. 1987;20(11):1362–5.

Li D, Wu Y, Kim P, Shi L, Yang P, Majumdar A. Thermal conductivity of individual silicon nanowires. Appl Phys Lett. 2003;83(14):2934–6.

Berger LI. Properties of semiconductors. In: Lide DR, editor. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics. 88th ed. (Internet Version 2008). Boca Raton: CRC Press/Taylor and Francis; 2008. p. 12–77.

Shi L, Li D, Yu C, Jang W, Kim D, Yao Z, et al. Measuring thermal and thermoelectric properties of one-dimensional nano-structures using a microfabricated device. J Heat Transf. 2003;125(5):881–8.

Boukai AI, Bunimovich Y, Tahir-Kheli J, Yu JK, Goddard WA, Heath JR. Silicon nanowires as efficient thermoelectric materials. Nature. 2008;451(7175):168–71.

Sultan R, Avery AD, Stiehl G, Zink BL. Thermal conductivity of micromachined low-stress silicon-nitride beams from 77 to 325 K. J Appl Phys. 2009;105(4):43501–7.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation (Grant ECS-05-08514) and the Office of Naval Research (Award number N00014-06-1-0234). A. Arriagada acknowledges Mina Sierou for many helpful discussions regarding COMSOL Multiphysics® simulations.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Arriagada, A., Yu, E.T. & Bandaru, P.R. Determination of thermal parameters of one-dimensional nanostructures through a thermal transient method. J Therm Anal Calorim 97, 1023–1026 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-009-0274-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-009-0274-2