Abstract

The present study attempts to give an account of how students represent writing task in an EAP course. Further, the study is intended to discover if learners’ mental representation of writing would contribute to their written performance. During a 16-week term, students were instructed to practice writing as a problem solving activity. At almost the end of the term, they were prompted to write on what they thought writing task was like and also an essay on an argumentative topic. The results revealed that students could conceptualize the instructed recursive model of writing as a process-based, multi-dimensional and integrated activity inducing self-direction and organization while holding in low regard the product view of writing. The findings also demonstrated that task representation was related to the students’ writing performance, with process oriented students significantly outperforming the product-oriented ones. Also, it was found that task representation components (ideational, linguistic, textual, interpersonal) had a significant relationship with the written performance (\(\upbeta =0.59\); Sig.: 0.006). The study can have both theoretical and practical implications with regard to the factors involving the students’ writing internal processes and their effects on written performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most EAP students find it hard to overcome the burden of writing effectively in the academic contexts though they realize the significance of writing for their academic success (Ganobcsik-Williams 2006). The difficulty of the job has been addressed from different perspectives. Although quite a few studies undertaken in regard to L2 writing have relatively cast light over the quality of students’ writing, the results, nevertheless, have been quite mixed, especially with respect to the effects of EAP courses on L2 writing performances. In their research, Shaw and Liu (1998) showed that their students in EAP writing classes could develop their formal language ability at the expense of no significant changes in accuracy or complexity. In contrast, Storch and Tapper (2009) displayed their students’ improvement in linguistic accuracy. Other studies have reported the development of writing performance and overall proficiency of the students in their writing classes (e.g., Elder and O’Loughlin 2003; Green and Weir 2003). Due to the discrepancies in the results so far reported, there seems to be a pressing need to discover how L2 writers conceptualize and thus approach a writing task. This may contribute to finding out why the students have not been able to develop this essential ability. In this line of thinking, we try to study the EFL writers’ internal processes as they relate to the writing task and the effects of these internal processes upon their writing performance.

To analyze the internal processes, a number of researchers have attempted to probe into the nature of writers’ task representation with the hope of shedding light on their beliefs about their writing task (Wolfersberger 2007). Task representation is described as a process of problem-solving which involves the grasp of a rhetorical problem created by the writing task, the goals of the writer in tackling the task, and the strategies employed by the writer while composing the task (Flower 1990). This description of task representation brings it close to the concept of psychological mental models defined as individuals’ mental processes which are utilized while reasoning or attempting to solve particular problems through the activation of their purposes (Doyle et al. 2002). As such, mental models (MMs) can be perceived as sets of belief systems developed by individuals to cope with the specific task demands posed by such problem-solving situations as composing EFL writing. These mental models serve as dynamic working models (Johnson-Laird 1983) through which writers can try to achieve the writing task assigned to them. Mental models, as Vygotsky (cited in Lantolf and Poehner 2014) asserts, depend on culture, interaction, and processes of internalization and imitation. Elaborating on Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, Lantolf (2006) contends that human mind is mediated through symbolic tools or artefacts which within the zone of proximal development enable L2 learners to develop their minds and also master their thought. In this line of inquiry, Lantolf and Thorne (2006) state that writing activity can act as a meditational artifact to control thinking due to the reversibility of the linguistic sign. Thus Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory can be employed as an analytical lens for investigating the development of L2 writing and the way learners can represent the task of writing in their minds, and capitalize on it to improve their writing quality.

To date, researchers have studied writing task representation in different ways, from reading-to-write tasks producing complex cognitive interpretations of one task in the process of writing to studies focusing on writers’ mental representations of descriptive and expository texts (Nicolas-Conesa et al. 2014). In all these studies, the writers’ interpretations of the writing task have been underscored.

However, there seems to be a dearth of studies dealing with the issue, especially where the students’ representation of writing task within a writing class can be developmentally guided towards a problem-solving view of the task. To fill the gap, the present study attempts to explore the EFL students’ mental models as can be developed in an EAP class and also discover the relationship between the task representation and written performance of the students. In other words, this study intends to first analyze the students’ mental models of writing and second see how the written performance of EFL university students is affected by the way that they would represent the writing task. The writers’ mental models or task representations are argued to be responsible for activating a working procedure for EFL writing (Hayes et al. 1987).

Previous Studies

One of the earliest attempts of probing into task representations was made by Flower (1990) who investigated L1 writers’ task representation while writing through exploiting think aloud protocols and the personal accounts of their writing experience. She found out that different interpretations of one task among different writers led to distinct goals, different organizational patterns, and diverse plans and strategies for the accomplishment of the task. Ruiz-Funes (2001) studied students’ task representation as realized in the end of term written products. She gathered that the quality of the produced texts was not related to the students’ complexity of task representation in L2. Wolfersberger (2007) investigated task representation of L2 writers while writing, focusing on the L2 task representation’s dynamic process and its relationship with L2 writers’ written performance. He examined the students’ previous experiences in L2 writing to discover any possible effect upon the shape of the task in the processing stages of the compositions. The findings however did not come up with any relationship between task representation and their performances.

Apart from the above studies on the task representation analysis while composing, a number of others have tried to look into the writers’ mental models defined as their beliefs or stored task representation that can guide the writers’ performance. Manchon (2009) investigated L2 writers’ beliefs, and how their beliefs and conceptions of the task could direct and shape their written performance. Following Manchon (2009), Manchon and Roca de Larios (2011) examined mental models of writing among L2 writers. The beliefs and conceptions of the writers, or more specifically, their mental models, were found as vital factors in specifying the learners’ purposes for writing, their problem-solving behavior and their consideration of various aspects of writing task. Through self-reports of the changes in their conceptualization of the writing activity, these writers paid attention to various discoursal features involved in the production of their texts such as the ideational, textual, and linguistic aspects. Moreover, the changes in task conceptualization resulted in the writers’ development of goals and also their linguistic concerns.

In a recent study, Nicolas-Conesa et al. (2014) investigated the L2 writers’ internal processes through examining the development of the students’ stored beliefs and their effects on the task, goals and their writing quality. The results indicated that the L2 writers could develop their mental conception of writing into more sophisticated models, with the activation of a hierarchical network of goals for composing. The writers’ views were also shown to be related to their level of writing achievement.

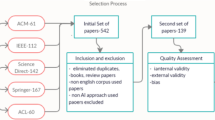

Method

Participants

This study involved 31 university students, 18 female and 13 male with the age range of 18–21, who had enrolled in an EAP course at an Iranian University. Ahead of this course, these students had finished two general English courses successfully and were at an advanced level of English proficiency as determined through Oxford Placement Test (OPT) (X \(=\) 48.7, SD \(=\) 8.3). The course lasted for 16 weeks and was defined around improving students’ writing ability in English, focusing on the processes at work in developing writing tasks. They met each other on a weekly two 1-h session basis and learned how to compose academic texts and also how to analyze writing samples. To fulfill the adopted process approach, the students were assigned the tasks of generating ideas, developing and composing their ideas, editing, and revising their compositions jointly and individually. Students’ assignments were reviewed by the teacher as well at linguistic, textual, ideational and interpersonal levels, and finally rewritten by the students to meet the requirements. The students were also required to keep self-reflective journals designed to enhance their fluency, confidence, and critical thought in writing. Their end of the term assessment was determined both through their in-course formative activities and final summative examination of composing an argumentative text of about 300–400 words on a designated topic.

Data Collection

Written Texts

In week 13, three weeks before the end of the course, the students were given a prompt (see “Appendix 1”) to write on the writing task representation using the journals they had been asked to keep. This point in time (i.e., week 13) was considered important as it could provide students with enough time to learn from their course and subsequently transfer their learning (Haskell 2001). It also enabled us to compare the students’ stated points on the task representation with their written performance. Finally, they were required to write an argumentative essay on a particular topic (Raimes 1987), as a part of their course assessment, which also served as supplying information on their written performance for the present study (see “Appendix 1”).

The prompt on task representation and the argumentative essays were both administered in the classroom, with the former one taking 1 h and the latter (i.e., argumentative essay) 2 h to complete. It is worth mentioning that the journals students had kept allowed them to reflect on their own views during the semester, thus developing and enhancing their opinions on the task representation.

Coding the Students’ Task Representations

The students’ produced texts (N \(=\) 31; Average word size per text \(=\) 208.2) on their representation of writing task were recursively read by the researchers to identify the thematic units (TU). To define a thematic unit operationally, we followed Luk (2008), who viewed it as ’a set of statements conveying one identifiable coherent idea’ (p. 628). Recurrent patterns of analysis or thematic units were coded blindly by the researchers using the comparative method suggested by Miles and Huberman (1994). The inter-coder reliability yielded a Koppa of 0.88; the differences were later negotiated and resolved.

The coding scheme used 1 to represent the category of task representation which was subdivided into the two levels of (a) learners’ orientation towards writing, and (b) the dimensions of writing (Nicolas-Conesa et al. 2014). The learners’ orientation towards writing was dichotomized into either process (PS) or product (PT) approach (Wolfersberger 2007). Thus, to make the coding job more manageable, the task representation was designated through 1-PT or 1-PS, which identified the TUs as ’Task representation, Product, and Process’, respectively. Following the previous research (Nicolas-Conesa et al. 2014), the process approach was defined as involving a recursive task with one or several stages and steps of writing, while the product approach encapsulated the task as static elements without any concern for explicit stages of development. The following examples (Process and Product Orientations) are taken from students’ assignments. The parentheses contain student numbers.

Examples:

Student (15)-1-PS: ‘It is necessary to think of improving writing by the first, second, ... drafts so that we can make better use of our abilities in various conditions.’

Student (21)-1-PT: ‘I believe writing means the selection and use of macrostructures for clear organizations.’

To identify the dimensions of writing, the study capitalized on the research by Manchon and Roca de Larios’ (2011) research, which assumes the writing facets to be ideational, textual and linguistic. Ideational dimension concerns writers’ generation of ideas; textual relates to the organization of ideas through coherence and cohesion; and linguistic level involves grammar and vocabulary. In this research, we added a fourth dimension, ’interpersonal’. This is because writing is arguably directed towards and addresses the concerns of the audience as well (Halliday and Matthiessen 2013). It is our belief that writing always adapts its content to the readers, making the text reader-friendly. Thus, interpersonal dimension is taken as the writer’s attempts to convey the message so effectively that it can be received unambiguously by the reader. This part of data analysis, for the ease of job, used the designations of 1-ID, 1-T, 1-L, and 1-IN for ideational, textual, linguistic, and interpersonal dimensions, respectively. Below the four dimensions are exemplified.

Examples:

Student (6)-1-ID: ‘The first step in writing is to think both deeply and broadly as to what to include in your essay.’

Student (17)-1-T: ‘Also, writers should link the parts of a paragraph together in an organized way.’

Student (24)-1-L: ‘I think a majority of writers are concerned about the correct grammar of their writing.’

Student (18)-1-IN: ‘We have to pay attention to our readers as well because they need to read the texts easily.’

Scoring the Argumentative Essays

The students’ essays (N \(=\) 31; Average word size per text \(=\) 347.5) were analyzed and rated through a researcher-constructed method of evaluation, which involved four dimensions of content, language, organization, and appropriacy, each measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Raters were thus required to rate the essays by taking into account the four specified components to be scored along the scale of 1–5; 1 showed the lowest score on that component, say, content, and 5 the highest. Receiving the full score (i.e., 5) on each component would total 20 on the four components (“Appendix 2”).

The four dimensions in evaluation were roughly similar to the task representation facets (i.e., ideational, linguistic, textual, interpersonal). This congruity of measures was intended to make the comparison of the two issues (task representation and writing performance) more plausible to see if students would carry out what they had been instructed.

Results and Discussion

This research was primarily concerned with the analysis of the EFL writers’ mental perception of the task of writing. To unfold the writers’ mental models, they were prompted to explain, in writing, what they thought writing would mean to them or how writing would be represented in their minds. Student writers’ representation of the task or what they have already experienced and developed conceptually is widely acknowledged to affect their performance in writing (Manchon 2009; Manchon and Roca de Larios 2011; Johnson-Laird 1983). As a piece of evidence, Nicolas-Conesa et al. (2014) showed that writers’ mental models can develop over time, affecting their performance in composing tasks.

In the present study, the results of the analysis revealed that the participants as a whole have developed a process-oriented model of writing. In fact, the participants characterized the writing task through 218 thematic units, of which 147 cases (67.4 %) were identified as process oriented themes (Table 1). The finding that the majority of the students were oriented towards the process approach could be attributed to the class-based attempts made to indoctrinate the students with iterative decision making and rewriting procedures. In this regard, Swain (1985) argues that the students who are instructed to learn the language through problem solving activities and revising procedures experience the constant process of noticing and are empowered to overcome their own problems. Thus, writers, through exposure to and exposition of the process orientation in the classroom, take an initiative to develop a new mental model of how to hold a process or problem-solving view towards the writing task (Nicolas-Conesa et al. 2014).

Yet, the 32.6 % product orientation can obviously be taken as an important indicator of writers’ appreciation for static features as well. This product view of writing task can be illuminating in the following way. It seems that EFL writers persist with their initial product view of writing despite the fact that their EAP writing class has been structured around process orientation. The number (31 participants), though with a lower frequency of themes in total (NTU=71), as compared with process group showed that each writer had at least one product-related statement for task representation. In fact, this revealed that students tended to keep a dual-faceted orientation of writing involving both product and process dimensions. A word of caution is in order. A more in-depth analysis and developmental design can more effectively throw light over the process of development in writers’ mental representations of writing task. The findings of the study, however, support Manchon and Roca de Larios (2011), who discovered that their students could get oriented towards the writing task as being more of a problem solving activity or what we have called here a process orientation.

Apart from the two orientations, the participants of the study also demonstrated that the writing task could be represented through four different complementary dimensions (Table 1). This finding basically points to the multidimensionality of the writing view held by the EFL students (Devine et al. 1993). In other words, our students showed to hold a non-monolithic view of the writing task, very important in leading them to composing integrated and well-textured tasks in writing. As seen in Table 1, the participants focused more intensively on the linguistic dimension (44.5 %), followed by ideational (28.4 %), textual (16.5 %, and finally interpersonal (10.6 %).

Further analysis (Table 2) also indicated that the ‘process’ group made significantly more use of the four dimensions than the ‘product’ group on the whole (Sig: 0.001, P=0.05). This was in line with Segev-Miller’s (2004) argument that writing task requires a high level of control which can be accommodated through a process approach. Since process-oriented students follow the procedural steps in writing, they exercise more meta/cognitive strategies for dealing with compositional aspects of language tasks than their product-oriented counterparts. Consequently, it can be argued that strategic mechanisms of this kind help students to be attentive to different layers of knowledge formation and transformation, and more elaboration of the writing task perception into its relevant constituent dimensions (i.e., ideational, linguistic, ...). In other words, the results demonstrate that students’ orientation (process vs. product) tends to coincide well with their ability in task representation at multi-levels.

The analysis of differences in the four dimensions also revealed that they were meaningfully different (\(x^{2}\)(3)=46.324, Sig.=0.000).

In regard to the dimensions of writing task as shown above, the following points have to be explained. The preponderance of the ’linguistic dimension’ used by the writers seems to be especially significant in the context of EFL writing class. Contrary to similar studies (e.g., Nicolas-Conesa et al. 2014), this research finds ‘ideational dimension’ as the commonly expected aspect in writing relegated to a secondary position. For one reason, there appears to be a class-induced impetus behind this tendency whereby EFL writers are primarily required to align themselves with the demands of language accuracy and structure rather than instructed to generate ideas. Accordingly, one may contend that in foreign language writing classes it is the language, as the classes are so-called language classes, not the message that drives writers forward. For another, the EFL writers may deem the ideational dimension of their writing unrealistic and thus contrived in the imagined class context, not to be given so much credit as the linguistic dimension which is always called for by the teachers. Also, it could be argued that the L2 writers’ linguistic dimension outcompetes the cognitive dimension (i.e., ideational) simply because the latter is more demanding and challenging to fulfill. Another important point to consider is that the participants have reported their writing views in this study through a task representation prompt, not considering the specific problems of an ongoing writing activity which could be otherwise accounted for through think-aloud methods (Roca de Larios et al. 2006).

The last two dimensions (textual and interpersonal) as the least recurrent facets can also be explained against the overarching significance accorded to the linguistic dimension in the study. Given the fact that textual dimension is associated with coherence and clarity in the expression of ideas, it is hardly surprising to find out that the participants did not attend to it sufficiently because the use of linguistic dimension, usually interpreted to include textual facet as well, already outweighed the ideational one. This may indicate that the writers feel compelled to first improve their linguistic ability, only to later conceptualize the task in terms of rhetorical features, organizational aspects, and higher levels of writing. Following Nicolas-Conesa et al. (2014), it may be further argued that the under-utilized textual facet of writing may indicate that the writers initially draw upon their common sense knowledge of this dimension acquired through general experience and only over long time can manage to alternatively use it. This point is, however, suggested to be separately addressed in the EAP context of writing.

As for the ‘interpersonal dimension’, writers were expected to allow a role for their audience while writing. But, the least frequency of this facet showed that the EFL writers tended to avoid taking into account their readers seriously. Socio-culturally, this means that writers of a special community or rhetorical stance may prefer to force their readers to elicit meaning and arrive at overall objectives of the writing on their own, thus opting for a reader responsible rather than writer responsible prose (Flower 1979). The finding can also indicate that these writers cognitively increase the ideational demands of writing at the cost of less engagement with their audience.

Overall, concerning the EFL writers’ representation of the composing task in the study, the following points need to be underscored. First, the participants of the study have developed their perceptions of writing from two classroom-based perspectives of ‘learning to write’ and ‘writing to learn’. The double perspective, as we believe, can inevitably confine students to the requirements of the EAP class where strict conditions of surface features of language, and thus limited functions of language, are emphasized and practiced. As such, these classes offer little in the way of higher level aspects of writing (e. g., ideational, textual, interpersonal). This deficiency seems to call for an enhancement of functional capacity of class- based instruction to involve more reliance on and value given to the higher levels of writing, especially higher regard for the expression of ideas than the language alone. That is, the EAP classes need to be geared around and upgraded to capture the prominence of the idea expression in the students’ writing so that the writers would not probably take the issue of concern on an unrealistic level. The above gap, we recommend, can be bridged through the addition and practice of a third perspective of ‘writing to communicate’ in the writing classes; the three perspectives could be merged into one three-pronged ‘learning to write how to communicate’ or ’writing to learn how to communicate’ perspective.

Second, the findings of the research have here been interpreted on a statistical frequency scale, which has to be cautiously interpreted. The frequency analysis of a phenomenon cannot clearly be an impeccable substitute for the underlying truth in the studied constructs. Put differently, that one dimension receives less frequency-based attention does not necessarily mean that it is of less significance. As a general rule of thumb, writers may assume that the ideational and linguistic dimensions of language implicitly and thus intrinsically make up for the dimensions of textual and interpersonal dimensions without any need for the latter two to be equally surfaced as well. Moreover, there is no external criterion against which to pass a judgment over the priorities of dimensions. At the present state of research on writing dimensions, we cannot assuredly claim how much of a dimension would truthfully constitute the construct.

Third, the analysis of our results, in line with Nicolas-Conesa et al. (2014) and opposite to the findings of Devine et al. (1993), reveals that the multidimensional dimensions stated for the writing task are integrative rather than fragmentary. That is, the writers in this study do not construe the facets of the task to be self-contained or independent but rather as complementing each other. This is well evidenced in the writers’ representations and illustrated in the following extract.

Student (22): ‘writing in my opinion is about making sure that your language is correct to convey your intention to your reader while considering if your reader is able to understand you clearly.’

As Hyland (2003) and Zhang (2005) contend, the differences between different studies in representing the writing dimensions as integrative or fragmented may lie in the cultural backgrounds of the participants especially if they have already developed a representation of academic writing in their first language. Additionally, the differences can result from the participants’ language proficiency levels. This is demonstrated in the differences of the results in this study and those in Nicolas-Conessa et al.’s (2014) compared with Devine et al.’s (1993) research, in which the first two studies investigated the writers of upper intermediate and advanced levels, respectively, while the latter study was concerned with the students of lower intermediate level. The findings of these researches compared indicate that the higher the level of proficiency, the greater the likelihood that the writers will present themselves integratively in their writing.

The second part of our investigation concerned the role that the mental models can play in students’ written performance. This issue is dealt with below.

As stated above, this study also tried to investigate the relationship between the task representation and participants’ written performance. The first part of this relationship concerns the participants’ orientations, divided into process and product, and their scores on the writing task. It must be noted that the written performance of the participants was assessed through the researchers’ rating based on four evaluative dimensions, each of which rated on a 5- point scale, totaling 20.

The analysis revealed that the participants, in aggregate, obtained the mean score of 15.24, with product oriented group achieving the mean of 14.16 and the process oriented one getting 16.31 (Table 3). Further analysis of the above means through independent t test performed due to the normal distribution of the scores (Table 3), revealed that the two groups (product vs. process) were meaningfully different in their written performances (Table 4). This comparison was based on the fact that all the participants (N \(=\) 31) defined the task as a product and 19 of them defined it as a process. Therefore, we had just 12 participants truly belonging to the product and the remainder (N \(=\) 19) to process group.

From the results obtained, it can be stated that task representations held by the writers and especially the orientations that they have adopted towards writing play a role in in their writing success. In this line of thinking, several other studies have also argued that adequate writing task representation in terms of ‘process’ encourages the writers to exercise a high level of control for planning and revising their assigned task, which can lead to better performance (Smeets and Solé 2008; Fitzgerald and Shanahan 2000; Segev-Miller 2004). The process approach, as shown in the results of the writers’ performances, displays that our writers most probably go through a rhetorical situation in which they conjure up teachers’ expectations, texts they have read and written, conventions, possible language, and also their own knowledge, needs, and desires (Flower 1990).

As stated before, the writers’ performances have been evaluated through five measures of content, language, organization and appropriacy, as also followed and practiced in the classroom. These measures, as practiced in the classroom, have clearly made writers conscious of their teacher’s preferences as the criteria for assessment and have contributed to their becoming self-directed writers (Beyer 1987). Nicolas-Conesa et al. (2014) similarly found out that the EFL writers, through the adoption of a process approach, learn how to dynamically set their own directions, which as postulated in the self-regulation models, can lead to a movement from a postactional stage of writing to a preactional one in motivational models, resulting in further improvement of writing (Dornyei and Otto 1998). From a similar perspective, Cumming (2012) argues that in the case of writers with a process view, they are likely to have directions for their writing at the beginning, and also develop their directions through further follow-up procedures after they are done with the job. These ideas show that writing can start off as an instructed process, turning into a self-directed one through success-induced motivation, and evolve further cyclically as if through a self-sustaining chain reaction.

Another possible explanation for the process oriented group’s better performance could be the fact that through practice and instruction, the writers are enabled to transform their theoretical knowledge (i.e., mental representations) into what they desire to serve, a model of intertextual integration known as knowledge transforming model (Bereiter and Scardamalia 1987).

The analysis also showed the relationship between dimensions of writing and their roles in the writers’ performances. The statistical analysis of the data indicated that a linear relationship could be established between writers’ representation of task and their writing performance (Table 5). In other words, the relationship between task representation components and writing performance showed a regression coefficient of .48, and also 23.7 % of linear change (coefficient of determination).

The regression analysis showed that the relationship is statistically significant (Table 6), with a one unit increment in the task representation leading to about 0.59 % (slope of regression line) increase in the writing performance. Thus the regression model for the relationship could be represented as follows:

Kantz (1990) argues that writers interpret in their minds the writing tasks in different ways which accordingly lead to papers of different quality. This explanation is well evidenced in the results our students reached as they realized that certain qualities of their compositions were to be rated higher. That is, students’ writing performances were here shown to be associated with the ways they had represented their models through. The rating of the students’ essays revealed that the dimensions of writing represented in students’ mental models (i.e., ideational, linguistic, textual and interpersonal) had also received the raters’ attention in their scoring, with the two aspects of ’language and organization’ corresponding to the ’linguistic and textual’ dimensions given the highest scores of 4.74 and 4 each out of 5, respectively. This finding indicates that student writers try to comply with the teachers’ expectations and their preferred aspects of writing quality. Thus writing may be rendered as a goal- and self-directed process since through teachers’ heuristic techniques students come to manipulate the conditions in the desired direction to fulfill the pre-instructed criteria. The implication for the teachers is that they need to put more premium on the dynamics and dimensions of writing so as to encourage students to develop more balanced mental models of the task (Cumming 2012). This issue, if accorded enough significance, could contribute to writing high quality papers.

Conclusion

The present study investigated the EFL learners’ mental models of writing in an EAP class and also the relationship between mental models and writing performance. The overall results point to the fact that EFL writers develop predominantly process oriented models of writing while simultaneously keeping a low level of product view. The mental models of writing were also shown to be related to writing performances. The findings of the study provide insights into the learners’ task representation and their engagement in writing.

The results support previous L2 writing studies (e.g., Manchon 2009; Nicolas-Conesa et al. 2014), which argue that learners can develop their perception of the writing task into a problem solving perspective if instructed how to practically go through the steps and stages of composing the task, resulting in multiple and integrated dimensions for writing. This perspective could be argued to have been practically rewarding by discovering that the EFL writers in this study who been been traditionally directed towards higher concern for product aspects of language had become capable of adopting process-based mental representation and manifesting it in their writing task performance. The results of the study also confirmed those reached by Smeets and Solé (2008), who found that writing instruction could have an impact on students’ task representation and that those students capable of representing the task adequately seemed to be better at carrying it out (Smeets and Solé 2008).

The results of the study also fit very well into the sociocultural theory of language learning where instructional activities can promote learner abilities and help understand L2 development (Lantolf and Poehner 2014). Following the above theory and for the first time, Negueruela (2003) introduced systemic-theoretical instruction (STI) to underscore the importance of abstract conceptual knowledge in schooling to bridge the gap between theory and practice envisioned by Vygotsky. As speculated by Negueruela (2003), the study in here also exemplifies STI, showing that mediated L2 development can be achieved via the mediator–learner dialogic interaction in the writing class. In other words, the reorientation of the learners in the classroom toward process-based writing can be taken as the learners’ appropriation of concept-based instructional material as symbolic tools for representing the task and thus for their own thinking. It must further be explained that writing task representations, as unfolded in the results of the study, reaffirm the significance of the STI’s role in transforming dialogic interactions and concepts into more accessible forms that learners may refer to as they try to develop new ways of thinking about a language task and how to manipulate it purposefully. As a piece of evidence for the purposive manipulation, the improvement in the learners’ quality of writing indicates that mediated development in L2 is basically concerned with ways of thinking and mental reconfiguration of the presumed tasks rather than pushing learners to find a correct discrete option among others.

Overall, it must be noted the results cannot be interpreted unrestrictedly for at least three methodological issues. One is that the study did not consider the important issue of how the process of task representation unfolds over a long time so as to clearly tackle the development and quality of writing dimensions. This discrepancy, however, can be captured through a design encompassing the longitudinal (or initial, medial, and final stages) progresses of the task and the effects of task models on performance. The second point is that the writers in this study presented their task representation models through a written prompt. This may not make students discharge what goes on in their minds, as compared with thinking aloud while doing the composing job. Thus to arrive at genuine representations of writing, it is suggested that students be required to think aloud about what goes on in their minds. Some other ways of fine-grained analyses such as post-writing interviews can also be revealing. The last methodological point to consider is that the students’ proficiency levels should be accounted for in such studies. As it is argued, the less skilled language learners may not approach the task representations in the same way as skilled learners (Nicolas-Conesa et al. 2014). Thus given the importance of language proficiency, the studies need to delve into how writing models develop and affect the quality of writing through the working of this variable, which may lead to redefining the interrelationships.

The present study not only gives an overall notion of mental models to students but also will inform them which components of the mental models can contribute more to the developing of a better writing performance. The learners are already preached enough on the importance of accuracy and linguistic intelligibility of their writing but this study underscores the other facets of mental models especially the interpersonal aspect which is introduced and discussed in the present study. Making the students conscious of the reader can help them develop the notion of tone in writing. Moreover, as no piece of writing can be separated from the intentionality which has made it, when the notions of the writers towards the task, i.e., writing, becomes sophisticated, some light is shed on their attitude towards writing activity as well, and as such their beliefs, ideas, and even their macrocosmic outlook about EAP might develop further.

References

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cumming, A. (2012). Goal theory and second-language writing development, two ways. In R. Manchon (Ed.), L2 writing development: Multiple perspectives (pp. 135–164). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Devine, J., Railey, K., & Boshoff, P. (1993). The implications of cognitive models in L1 and L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 2, 203–225.

Dornyei, Z., & Otto, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43–69.

Doyle, J. K., Ford, D. N., Radzicki, M. J., & Trees, W. S. (2002). Mental models of dynamic systems. In Y. Barlas (Ed.), System dynamics and integrated modeling. Encyclopedia of life support systems (EOLSS) (Vol. 2). Oxford: UNESCO, EOLSS Publishers.

Elder, C., & O’Loughlin, K. (2003). Investigating the relationship between intensive English language study and band score gains on IELTS. IELTS Research Reports (vol. 4, pp. 207–254). Canberra: IELTS Australia.

Fitzgerald, J., & Shanahan, T. (2000). Reading and writing relations and their development. Educational Psychologist, 35(1), 39–50.

Flower, L. (1979). Writer-based prose: A cognitive basis for problems in writing. College English, 41(1), 19–37.

Flower, L. (1990). The role of task representation in reading-to-write. In L. Flower, V. Stein, J. Ackerman, M. J. Kantz, K. McCormick, & W. C. Peck (Eds.), Reading to write: Exploring a cognitive and social process (pp. 35–75). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ganobcsik-Williams, L. (Ed.). (2006). Teaching academic writing in UK higher education: Theories, practices and models. Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Green, A., & Weir, C. (2003). Monitoring score gain on the IELTS academic writing module in EAP programmes of varying duration. Phase 2 report. Cambridge: UCLES.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2013). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Haskell, R. E. (2001). Transfer of learning: Cognition, instruction, and reasoning. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Hayes, J. R., Flower, L., Schriver, K. A., Stratman, J. F., & Carey, L. (1987). Cognitive processes in revision. In S. Rosenberg (Ed.), Advances in applied psycholinguistics: Vol. 2, Reading, writing, and language learning (pp. 176–240). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hyland, K. (2003). Genre-based pedagogies: A social response to process. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(1), 17–29.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983). Mental models: Towards a cognitive science of language, inference, and consciousness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Kantz, M. J. (1990). Promises of coherence, weak content, and strong organization: An analysis of the students’ texts. In L. Flower, V. Stein, J. Ackerman, M. J. Kantz, K. McCormick, & W. C. Peck (Eds.), Reading-to-write: Exploring a cognitive and social process. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lantolf, J. P. (2006). Sociocultural theory and L2. State of the art. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 67–109.

Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2014). Sociocultural theory and the pedagogical imperative in L2 education: Vygotskian praxis and the research/practice divide. London, England: Routledge.

Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Luk, J. (2008). Assessing teaching practicum reflections: Distinguishing discourse features of the “high” and “low” grade reports. System, 36, 624–641.

Manchon, R. M. (2009). Task conceptualization and writing development: Dynamics of change in a task-based EAP course. Paper presented at the TBLT 2009 conference.

Manchon, R. M. (Ed.). (2011). Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an additional language. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Manchon, R. M., & Roca de Larios, J. (2011). Writing to learn in FL contexts: Exploring learners’ perceptions of the language learning potential of L2 writing. In R. M. Mancho’n (Ed.), Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an additional language (pp. 181–207). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Negueruela, E. (2003). A sociocultural approach to the teaching and learning of second languages: Systemic-theoretical instruction and L2 development. (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation), The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Nicolas-Conesa, F., Roca de Larios, J., & Coyle, Y. (2014). Development of EFL students’ mental models of writing and their effects on performance. Journal of Second Language Writing, 24, 1–19.

Raimes, A. (1987). Language proficiency, writing ability, and composing strategies: A study of ESL college student writers. Language Learning, 37, 439–467.

Roca de Larios, J., Mancho’n, R. M., & Murphy, L. (2006). Generating text in native and foreign language writing: A temporal analysis of problem-solving formulation processes. The Modern Language Journal, 90(1), 100–114.

Ruiz-Funes, M. (2001). Task representation in foreign language reading-to-write. Foreign Language Annals, 34, 226–234.

Segev-Miller, R. (2004). Writing from sources: the effect of explicit instruction on college students’ processes and products. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 4, 5–33.

Shaw, P., & Liu, E. T. K. (1998). What develops in the development of second-language writing. Applied Linguistics, 19, 225–254.

Smeets, W., & Solé, I. (2008). How adequate task representation can help students write a successful synthesis. Zeitschrifts Schreiben . http://www.zeitschrift-schreiben.eu/Beitraege/smeets_Adequate_Task.pd.

Storch, N., & Tapper, J. (2009). The impact of an EAP course on postgraduate writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 8(3), 207–223.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition. Cambridge, MA: Newbury House.

Wolfersberger, M. A. (2007). Second language writing from sources: An ethnographic study of an argument essay task. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Zhang, Y. (2005). Task interpretation & ESL writers’ writing experience. Paper presented at the 2nd annual ICIC conference on intercultural rhetoric and written discourse Indiana University-Purdue University.

Acknowledgments

This study was not funded by any institute, organization or university but conducted through the authors’ mutual agreement and division of labor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study did not contain any animal-related investigation, and all the procedures involving the human participants have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and the informed consent from the individual participants obtained on the condition of anonymity and confidentiality.

Appendices

Appendix 1

-

1.

Prompt on task representation adapted from Nicolas-Conesa et al. (2014)

According to what you have learned in your writing course, please write a journal entry trying to explain to a prospective student in our department what you think good academic writing is and what it involves.

-

2.

Prompt for writing task (Argumentative Essay) adopted from Raimes (1987)

Success in education is influenced more by the students’ home life and training as a child than by the quality and effectiveness of the educational program. Do you agree or disagree?

Appendix 2

Rating scale Raters were required to rate the essays using the five specified components, each to be scored along the scale of 1–5; 1 shows the lowest score on that component, say, content, and 5 the highest. Receiving the full score on each component would result in 20. For example, if a student obtains 5 on all the components, his total score will be 20.

Components/points | Description | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Content | Meaningful and relevant arguments | |||||

Language | Correct use of language: structure, vocabulary, spelling, punctuation | |||||

Organization | Clear pattern of development: main ideas, supporting materials, cohesion and coherence | |||||

Appropriacy | Smooth, interesting, clear flow of information to be effortlessly received by the reader | |||||

Total score |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zarei, G.R., Pourghasemian, H. & Jalali, H. Language Learners’ Writing Task Representation and Its Effect on Written Performance in an EFL Context. J Psycholinguist Res 46, 567–581 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-016-9452-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-016-9452-0