Abstract

Purpose This systematic review analyzed the effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions on the employment and functioning of people with intellectual disabilities (ID), as well as barriers and facilitators of employment. Methods This was a systematic review of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. The outcomes were employment, transition to the open labor market and functioning. The review included qualitative studies of employment barriers and facilitators. The population comprised people with ID aged 16–68 years. Peer-reviewed articles published in English between January 1990 and February 2019 were obtained from the databases Cinahl, the Cochrane Library, Embase, Eric, Medic, Medline, OTseeker, Pedro, PsycInfo, PubMed, Socindex, and the Web of Science. We also searched Google Scholar and Base. The modified selection instrument (PIOS: participants, intervention, outcome, and study design) used in the selection of the articles depended on the selection criteria. Results Ten quantitative (one randomized controlled, one concurrently controlled, and eight cohort studies), six qualitative studies, one multimethod study, and 21 case studies met the inclusion criteria. The quantitative studies showed that secondary education increases employment among people with ID when it includes work experience and personal support services. Supported employment also increased employment in the open labor market, which sheltered work did not. The barriers to employment were the use of sheltered work, discrimination in vocational experience, the use of class teaching, and deficient work experience while still at school. The facilitators of employment were one’s own activity, the support of one’s family, job coaching, a well-designed work environment, appreciation of one’s work, support form one’s employer and work organization, knowledge and experience of employment during secondary education, and for entrepreneurs, the use of a support person. Conclusions The employment of people with ID can be improved through secondary education including proper teaching methods and personal support services, the use of supported work, workplace accommodations and support from one’s family and employer. These results can be utilized in the development of rehabilitation, education, and the employment of people with ID, to allow them the opportunity to work in the open labor market and participate in society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Employment is one of the primary goals of people with intellectual disabilities (ID) [1, 2]. Employment can lead to positive psychosocial and economic benefits for people with ID, including a sense of purpose, opportunities for new friendships [1, 2], health [3] and better quality of life [4, 5].

People with ID seldom work in the open labor market and the proportion of people with ID in employment varies between countries. For example, in Finland, it is 3% of working-age people with ID [6], in England 5–11% [7,8,9,10], and in the USA, 10% [11].

The prevalence of ID is about 1% of the population, but it differs between countries [12]. In Finland, it is 1% [13, 14], as in most European countries [15]. In Finland, 0.8% of working-aged people have ID, which means 25,000 people [6].

Rehabilitation is a goal-oriented process, which here aims to enable people with ID to reach an optimum mental, physical and social functional level, thereby providing them with the tools required to change their lives [16]. People with ID should receive services that support their functioning, self-determination and participation [2, 17]. In the last years, instead of using a system-centered approach, services for people with ID and other disabilities have begun to use a person-centered approach, tailoring services around the individual rather than enforcing a one-size-fits-all principle [2, 18, 19]. According to Austin and Lee [20], job-related services (job search assistance, job placement, job readiness training, on-the-job support services) significantly predicted the employment outcomes of people with ID. However, they found no significant relationship between personal services (diagnosis and treatment, counseling and guidance, transportation, maintenance, miscellaneous training) and employment outcomes.

Sheltered work or workshops are one form of rehabilitation for people with ID. One of the main tenets often cited by supporters of sheltered workshops is that center-based programs provide employment opportunities for people with ID in a segregated environment by building up their vocational and social skills [21, 22]. However, young adults with mild to moderate ID also have difficulties transitioning from sheltered workshops to the open labor market. Moreover, parents’ overprotection, important friendships, and the attitudes of employers and co-workers can be barriers during this transition process [22].

In this review, the term intellectual disability (ID) refers to people who have a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn new skills (impaired intelligence), and who have reduced ability to cope independently (restricted social functioning). In the United Kingdom (UK) the term ‘people with learning disabilities’ (LD) is used to describe those referred to elsewhere as people with ‘intellectual disabilities’ or ‘developmental disabilities’ [23].

No reviews were found on the effects of rehabilitation on employment among people with ID. Some reviews, however, evaluated the effectiveness of rehabilitation on the functioning (activities of daily living, self-care skills, communication skills, and cognitive achievements) of people with ID [16], the effects of the person-centered planning of services for people with ID on different outcomes (i.e., employment) [17], and effects of technology use on employment [24]. The research questions were: 1) How effective are rehabilitation interventions for the employment of people with ID, 2) what are the barriers to and facilitators of employment of people with ID, and 3) what kind of individual support measures have been used to increase the work ability and functioning of people with ID?

The theoretical orientation guiding this study was the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework [25] (Fig. 1). The ICF identifies and classifies the domain of environmental factors, including rehabilitation, as one of its health-related domains [26,27,28]. ICF provides a detailed framework for describing disease experiences as a dynamic interaction between its components, and ‘core sets’, comprising lists of ICF categories [28]. The ICF identifies and classifies the component of environmental factors, including rehabilitation, as one of its health-related components [26, 27]. According to the ICF, these environmental factors can also be either barriers to or facilitators of employment for these individual [27].

The theoretical orientation that guided this study was the ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health) framework [25]

Methods

This systematic review analyzed the effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions on the employment and functioning of people with ID, as well as barriers and facilitators of employment. We included quantitative, qualitative, and multimethod studies, because they provided different knowledge regarding this phenomenon [29, 30]. Quantitative studies showed the effectiveness of rehabilitation; qualitative studies showed the process, facilitators and barriers; and multimethod studies combined these.

We used the modified selection instrument (PIOS: participants, intervention, outcome, and study design) [29, 31] to select the titles, abstracts, and full papers according to the selection criteria. The inclusion criteria for studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies such as concurrently controlled trials (CCTs), case–control studies, cohort studies, follow-up studies, and case studies that investigated the effectiveness of rehabilitation among people with ID. We expected the outcomes of the studies to be employment (supported or non-supported employment, transition from school to work, transition from sheltered workshop to employment), or functioning (job performance), and the population to comprise people with ID (developmental disabilities, learning disabilities, cognitive disabilities, mental retardation, mental handicaps), in the age group of 16–68 years.

We searched for articles published in English from January 1990 to February 2019. The databases we searched in February and October in 2016 and in February in 2019 included: Cinahl, the Cochrane Library, Embase, Eric, Medic, Medline, OTseeker, Pedro, PsycInfo, PubMed, Socindex and the Web of Science. In addition, we searched Google Scholar and Base. Our main search terms were: (1) intellectual disability, mental disability, mental retardation, mentally disabled persons; (2) employment, employability, sheltered work, work capacity, work ability, vocational status, career; (3) rehabilitation, treatment, therapy, training, career counseling, social support, education, program, intervention, assistive technology, counseling, mainstreaming; (4) outcomes, outcome assessment, randomized controlled trials, program evaluation, effectiveness, validation studies, evaluation studies, comparative studies, cost–benefit analysis, before-after and follow up. We also manually scanned reference lists of identified reviews for additional relevant articles. Full details of the search strategy are available (Supplementary material).

The review team comprised five researchers, whose areas of expertise were disability, ergonomics, rehabilitation, social sciences, interventions, systematic reviews, and quantitative and qualitative methodology. First, pairs of researchers independently reviewed titles and abstracts and made a unanimous decision. If consensus was not reached, a third researcher was consulted. The full texts of all the eligible articles and those whose eligibility could not be discerned from reading the abstract were obtained.

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included RCT and CCT studies using the checklist by van Tulder et al. [32], which has also been used in other reviews concerning rehabilitation [28, 33, 34] and workplace accommodation [35]. The checklist consisted of 11 criteria. Each item scored two points for ‘Yes’, one point for ‘Don’t know’, and 0 points for ‘No’. The item scores were summed into a single total score (range 0–22). Studies were considered to be of high methodological quality if the score was at least 11 out of 22, and of low methodological quality if they achieved fewer than 11 points [32].

The cohort studies and the mixed method study were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [36]. This assessment scale consists of eight items within the following three categories: selection of study groups (four items), comparability of groups (one item/two questions) and ascertainment of exposure/outcome (three items). The highest value for quality assessment is nine ‘stars’. One star is allocated for each item in the selection and outcome categories and two stars in the comparability category. Study quality was graded as follows: 1–3 stars (low quality), 4–6 stars (intermediate quality), and 7–9 stars (high quality) [36].

Three pairs of reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included qualitative studies using a modified version of the CASP method [37]. Any difference in the item scoring was resolved through discussion with the third author until consensus was achieved. This assessment tool consisted of evaluation criteria that are commonly acknowledged as crucial in qualitative research in the social sciences. The assessment tool involved 10 questions based on the following four main principles: The research should (1) provide a defensible research strategy that can answer the questions posed, (2) demonstrate rigor through systematic and transparent data collection, analysis and interpretation, (3) contribute to advancing wider knowledge and understanding, and (4) demonstrate credibility with plausible arguments about the significance of the findings. Each item scored ‘Yes’ or ‘No, depending on whether the topic was described sufficiently. An additional score of ‘Partially’ was added, as the original checklist was not able to adequately differentiate between the quality of the studies [38]. This addition resulted in three options: ‘Yes’ (2 points), ‘Partially’ (1 point), and ‘No’ (0 points). The higher the total score, the better the methodological quality, with a maximum score of 20. The studies were rated as being of high methodological quality if they achieved more than 10 points.

The case studies were assessed using eight questions from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) method [39]: (1) Were the demographic characteristics of the person attending clearly described? (2) Was the history of the person attending clearly described and presented in the timeline? (3) Was the current clinical condition of the person clearly described, (4) Were diagnostic tests or assessment methods and the results clearly described? (5) Was the intervention(s) or treatment procedure(s) clearly presented? (6) Was the post-intervention clinical condition clearly described? (7) Were adverse events (harms) or unanticipated events clearly described? (8) Does the case report provide takeaway lessons? Each question scored one point for ‘Yes’, two points for ‘No’, three points for ‘Unclear’, and four points for ‘Not applicable’.

All the reviewers participated in the data extraction, which was carried out separately to the quantitative, qualitative, and multimethod studies, and included details on the participants and descriptions of the rehabilitation and the outcomes. The meaningful concepts of each outcome were linked to the ICF categories [40, 41].

We descriptively synthesized the data using tables to describe the characteristics, results and quality of the included studies. Different tables were used to describe the quantitative, qualitative and case studies. We categorized the overall quality of the quantitative studies and their outcomes using the principles of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) [42]. The GRADE approach classifies the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low or very low. Randomized controlled studies’ evidence begins with strong and cohort studies with scant evidence on the basis of the assumption that randomization is the best method for controlling unknown factors. Five factors can weaken evidence: (1) the risk of bias, which results from the weakness of the research method and its implementation, (2) differences and inconsistencies between different studies, (3) indirectness of the results in comparison to the PICO criteria, (4) the inaccuracy of the results (the number of events and participants and their effect on confidence intervals) and (5) publication bias (Chapter 12, Cochrane Handbook). Thus, strong research evidence required at least two-high quality studies, the results of which were parallel. Moderate research results required one or several high-quality studies, the results of which were only slightly contradictory, or several adequate studies, the results of which were parallel. Scant research evidence meant that the research results had significant contradictions. No research evidence meant that no studies existed or that they were methodically weak.

Results

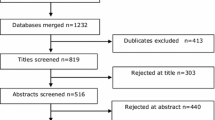

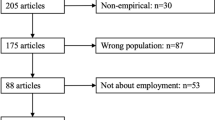

The search strategy identified 2618 references (Fig. 2). After removing duplicates, 1848 references remained. Two of the reviewer (altogether five) authors scrutinized all the titles and abstracts according to the inclusion criteria, and when information necessary for inclusion was lacking, they read the articles’ full texts. We obtained the full texts of 244 articles, and 38 studies met our inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of the included studies

Design and methods

Ten of the 38 included studies were quantitative (Table 1), six studies were qualitative (Table 2), one was a mixed methods study (Table 2), and 21 were case studies (Table 3, 4). The quantitative studies included one RCT [43], one CCT [44] and eight cohort studies [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. The qualitative studies included three interview studies [53,54,55], one interview and document study [56] and two ethnographic studies [57, 58]. The mixed method study [59] used structured interviews, focus group interviews and register analysis. The 21 case studies included five qualitative case studies [60,61,62,63,64] and 16 quantitative experiments [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80].

Participants

The total number of participants in the 38 studies was 2,41,080. The quantitative studies included 35–1,21,335 participants (n = 2,39,506), the qualitative studies 3–27 participants (n = 58), the mixed method study included 1452 participants and the case studies 1–10 participants (n = 64).

The age of the participants varied between 16 and 51. However, two qualitative studies [53, 54] and two case studies [62, 64] did not report the age of the participants. The proportion of men and women differed in the studies. In the quantitative studies, the proportion of women varied from 29% [50] to 58% [47]. In one qualitative study [56] all the participants were men and in another qualitative study [54] all the participants were women. Two studies [51, 59] did not report the gender of the participants. Seven studies reported the ethnicity of the participants [45, 47,48,49, 51, 52, 79].

Sixteen of the 38 studies reported the degree (mild, moderate, severe, profound) of ID as a background factor of the participants. People with mild ID participated in two cohort studies [48, 51], one qualitative study [57], and one case study [60]. People with either mild or moderate ID participated in three case studies [71, 75, 76], and people with moderate ID participated in two case studies [68, 80]. Renzaglia et al. [65], Simmons and Flexer [66], McGlashing-Johnson et al. [70], and West and Patton [73] focused on people with moderate or severe disabilities. People with severe ID were participants in three case studies [61, 67, 69]. Two studies [45, 77] reported the participants ‘level of functional capacity.

Seven of 38 studies concerned students [46, 48,49,50,51,52, 59], one study [47] concerned people who worked in sheltered workshops, and one study [44] concerned job-seekers. Four studies reported the occupation or work tasks of the participants as the background factors [69, 72, 75, 79].

Interventions

All studies contained various mixtures of intervention components. The interventions were carried out during secondary education, the transition from education to work, job-seeking and sheltered work. In general, the content of the intervention was briefly described. However, the stages of the intervention process were poorly reported, and the term rehabilitation was only seldom used.

During secondary education (Upper Secondary School for Pupils with ID) (ICF code d825), the students participated in different educational programs such as national programs, specially designed programs, vocational training and training activities or graduated with inadequate grades [50]. National programs focused on different parts of the labor market, for example, vehicles and transportation, hotels and restaurants, or social and healthcare. Some specially designed programs or individually tailored education were also on offer. The educational programs aimed to improve vocational qualifications and work awareness. The vocational qualification courses included assisting smaller pupils during classes, helping the janitor and working in the school kitchen. Work awareness training courses included watching videos about work, talking about presenting oneself at work, and health and safety instructions at school [46].

Some interventions included postschool and transition services (ICF code e5900) during education to improve the transition from education to work [43, 48, 49, 51, 55, 75]. Postschool services included postsecondary education institution accommodations and services, job training services, and life skills services [51]. Employment-related transition services were, for example, vocational assessment, career counseling, pre-vocational education, career-related technical or vocational education, pre-vocational or job readiness training, instructions for job-seeking, job shadowing, job coaching, special job skills training, placement support, internship or apprenticeship programs, work experience at school and other paid work experience [44, 48, 55, 65]. Job tasting was a short, unpaid, time-limited work experience period at the workplace which allowed people to sample a variety of different jobs and work cultures [44]. One qualitative study [57] analyzed the different actors’ experiences (schools, agencies, parents, other people) of the transition process and of employment (e310), and Fasching’s [54] study analyzed the experiences of people with ID of the transition from school to vocational training and employment.

The interventions also included supported work (supported employment, SE) (d855) [66], the use of a job coach or other support person (e340, e360) [45, 63], and designing personal solutions (e5900) [64]. One cohort study [46] analyzed whether attending a sheltered workshop (e5900) improved the employment outcomes of supported employees with ID.

Some interventions developed the independence of people with ID, applying the ICF model to the areas of body structures/functions, activities and participation. The interventions included support in psychological and behavioral issues (behavior) (b122) [56, 64] and communication abilities (d3) [67]; and a self-regulated problem-solving process in which students set their goals, developed and implemented their action plans (b164, d175) [70], made career-related decisions (d177) [75], were able to perform daily activities (d620, d630) [77], learned navigation skills such as finding the workplace and using public transportation (d4602) [78], and gradually reduced help in carrying out work tasks (d850) [72, 75, 77].

The use of digital solutions (e135) was intended to improve the daily work performance of people with ID in the open labor market. They could use these tools for receiving digital instructions for work tasks, work processes, work techniques or schedules. These solutions consisted of video modeling and audio coaching [72, 76], photo activity schedule books [71], smart phones [74], palmtop-based job aids [69], and self-operated auditory prompting systems [68, 80]. In the case studies, the interventions were carried out at workplaces such as restaurants [60, 66], hospitals [64], factories and warehouses [76], at markets [79], at schools [70, 72], and in conference rooms [80].

Outcomes

The outcomes were employment in the open labor market [43, 45, 47, 51, 52], transition from school to the open labor market [44, 46,47,48, 54, 55], and work performance [43, 44]. The outcomes in all 16 quantitative experiments were job skills and work performance [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80].

Study quality

The RCT study [43] was considered to be of high methodological quality, with scores of 11 out of 22, and the CCT study of Kilsby and Beyer [44] was of low methodological quality, with scores of 9 out of 22 according to van Tulder et al. [32]. The methodological quality of four cohort studies [47, 49, 50, 52] out of six were high, with the maximum of nine ‘stars’ according to Wells et al. [36]. Four cohort studies [45, 46, 48, 51] and one multimethod study [59] were considered to be of intermediate quality. All six qualitative studies [53,54,55,56,57,58] were considered to be of high quality, with scores ranging from 12 to 20 out of 20, according to the modified CASP method. (Table 6–9, Supplementary Files).

Effectiveness

The quantitative studies showed that supported work increases the employment of people with ID in the open labor market (Table 5). This result was based on one high-quality RCT study [43], one high-quality cohort study [47], and one moderate-quality cohort study [45] of altogether 16,947 people with ID. The quantitative studies also showed that both secondary and postsecondary education, including support services and work training, increased the transition of people with ID from school to the open labor market. The result was based on two high-quality cohort studies [50, 52] and three moderate-quality cohort studies [46, 48, 51] with 2,07,484 participants altogether.

However, on the basis of one high-quality RCT study [43] and one high-quality cohort study [47] covering a total of 15,089 participants, sheltered work did not increase the employment of people with ID in the open labor market (Table 5).

Barriers to and facilitators of employment

The qualitative studies concerned both the barriers to and the facilitators of employment in the open labor market (Table 2). The main barriers to employment were that the school and service system tried to guide people with ID towards traditional services such as sheltered work, sometimes against their own needs and interests [57]. However, these people’s work skills were not developed or their needs for support were not noticed in sheltered work [58]. Further barriers were discrimination in vocational experience after leaving school [54], poor experiences of class teaching and lack of work experience [58, 59].

The main facilitators of employment were people’s own activity and support from their families (e310) [57], effective job coaching (e360) [58], a well-designed work environment (e2) [61], appreciation of their work and support from their employer and work organization [56]. Other facilitators were the knowledge and experience of work during education [59], and for entrepreneurs, the use of a support person [53].

Work performance

The case studies showed that the use of digital solutions (e135) improved the work performance of people with ID in the open labor market. Work performance was measured as the percentage and rate of the tasks completed correctly [69, 72], the number of movements measured by a costume [76], the number of independent task changes [71], task steps [74], and percentage of intervals with task engagement and interactions [79].

Discussion

People with ID still face specific difficulties in gaining employment, which leads to inequality and social exclusion. Personally-tailored support services, occupational education, work experience and digital solutions can be used to help these individuals become employed in the open labor market.

This systematic review covered 38 studies (one RCT, one CCT, eight cohort studies, six qualitative studies, one multimethod study, and 21 case studies) that investigated the effectiveness of, barriers to or facilitators of employment among people with ID. The main outcome was employment in the open labor market through either supported or non-supported work, transition from education or from sheltered work to the open labor market, or functioning at work.

The quantitative studies showed that secondary and postsecondary education increases the employment of people with ID in the open labor market when it includes work experience and personal support services. Supported employment also increases employment in the open labor market, but sheltered work does not. The results were in line with those of earlier studies [2, 22, 81] which have shown the support of a job coach to be important for people with ID to find work, start work and continue at work among.

The qualitative studies showed the barriers to and facilitators of employment in the open labor market among people with ID. The barriers to employment were that the school and service system tried to guide people with ID towards traditional services such as sheltered work; that these people were discriminated against at school and had negative experiences of class teaching; and that they did not obtain work experience during education. These results support the findings of earlier studies [6, 22] which have shown low rates of employment when individuals come from sheltered work to the open labor market.

The facilitators of employment were the people’s own activity and support from their families, job coaches, work environments with necessary accommodations, appreciation of their work, support from an employer and work organization, knowledge and experience of work during education; and for entrepreneurs, the use of a support person. These findings support earlier results that have shown the importance of job coaches, employers’ responsibility [82] and personally designed support services [17, 18, 20].

The case studies showed that the work performance of people with ID could be improved through the use of digital solutions in daily work. However, digital solutions are only rarely used among people with ID. One reason may be the employees’ low competence in using digital systems, especially in sheltered work. Services in general are becoming increasingly digital, and this also requires more competence from people with ID [83].

Methodological discussion of included studies

Better reporting of basic methodological quality issues is generally required. A better description of participants, such as their gender, age, education, occupation and work experience is also needed when they are people with ID. We can conclude that people with ID are not seen as professionals because, although the studies described their diagnosis or disability well, they did not emphasize their competence and strengths, educational background or work experience. This is also true of studies of disability groups [35].

The studies included several different concepts of disability, rehabilitation, education, performance, and service systems. The concept of ID was defined as ‘developmental disability’, ‘mental retardation’, and ‘mental disability’. In the UK, ‘learning disability’ is used in the same way as ID, but in other countries, ‘learning disability’ means difficulties in learning without ID.

The articles failed to clearly report some elements of the interventions. They should have reported more information about the process and implementation schedule of rehabilitation, the initiator and the place. These shortfalls were found especially in cohort studies that focused on results and background factors such as the participants’ diagnoses.

Only few randomized controlled interventions have been carried out to enhance the employment among people with ID. This is possibly because of the low employment rate of people with ID, the low number of implemented rehabilitation programs, the ethical aspects of the study designs, negative attitudes, and a lack of financing instruments for such studies.

The outcomes in this review were employment in the open labor market in either supported or non-supported work, the transition from education or from sheltered work to the open labor market, or functioning at work. With the ICF model as a framework, these outcomes belong to ‘participation’. According to the ICF model, rehabilitation belongs to the ‘environmental factors’ that affect ‘activity’ (e.g., functioning) as do most of the synthesized themes from the analysis of qualitative studies. Obviously, the primary aim of rehabilitation on a personal level is to enhance the functioning and work ability of people with ID and to enable them to work in the open labor market. On the societal level, it is important to develop and implement solutions that enhance employment and participation and are simultaneously cost effective [17].

Strengths and limitations of this review

The strengths of this review included its multi-scientific research group, the comprehensiveness of the searches, the use of the ICF model as the theoretical framework, and the inclusion of a wide range of studies. The reviewers were experts in different scientific areas, including both quantitative and qualitative methodology and systematic reviews. Every effort was made to insure a comprehensive search. It is possible, however, that we did not find all the relevant studies. Another limitation was that the included studies used different concepts of ID. We included quantitative, qualitative, multimethod and case studies, which showed different kinds of knowledge regarding the process and the effectiveness of rehabilitation. However, this was also a shortcoming of this study because a meta-analyses of several types of results was complicated.

Quality assessment

This systematic review was of 38 studies (one RCT, one CCT, eight cohort studies, six qualitative studies, one multimethod study, and 21 case studies). The quality of the RCT study was assessed using the validated method of van Tulder et al. [32], which has also been used in several other reviews. The quality of the CCT study was low, mainly due to the fact that the study design did not include randomization, treatment allocation, blinding, or intention to treat the analysis. The quality of the cohort studies and the mixed method study were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [36]. The validity and reliability of this method was only partly evaluated in that the content validity and inter-rater reliability were established, but the criterion validity and intra-rater reliability were still in progress [36].

The original qualitative assessment tool CASP was not perceived as very powerful in differentiating between high- and low-quality studies. It only measured whether certain basic items that are essential identifiers of high-quality research were mentioned in the report. This type of measurement is crude and makes the scale difficult to use when some of the criteria are implicit in the study. Furthermore, a ‘Yes or No’ scale does not capture the fact that certain items in the CASP criteria may be more crucial to the quality of the study than others. Adding a third level of assessment, ‘Partially’, to the method, may solve the first problem. However, the second problem remains: Of the three problematic points of the qualitative studies evaluated, researcher effect is a self-evident fact connected to any study of social life, and is thus less informative than reporting the contribution of a particular study to existing knowledge. Although CASP offers a good basis for evaluating qualitative research reports, it can be further developed by giving different weights to different criteria.

The comparison of the results of the assessment of the quantitative and qualitative studies revealed a bias in that the quality assessment of qualitative studies resulted in several high-quality studies, whereas the quantitative assessment yielded only a few. This was, of course, partly due to different evaluation methods, but it may also be an indication of the different nature of these two types of research. Qualitative studies report interesting new observations about the ways in which participants observe, understand, or experience the phenomenon studied, while quantitative studies aim to make generalizations about possible causes and effects, and reveal other connections between the variables describing the phenomenon being studied. As the knowledge gained through qualitative research is descriptive and not numerical by nature, ranking studies is also difficult.

Conclusions

More people with ID could be employed through personally tailored services and measures. Tailoring can mean secondary or postsecondary education, including proper teaching methods and personal support services, the use of supported work, workplace accommodations, and the support of one’s family and employer. Our results can be utilized in the development of rehabilitation, education and employment of people with ID, to provide them with opportunities to work in the open labor market and to participate in society.

References

Test DW, Carver T, Ewers L, Haddad J, Person J. Longitudinal job satisfaction of persons in supported employment. Educ Train Mental Retard Dev Disabil. 2000;35(4):365–73.

Howarth E, Mann JR, Zhou H, McDermott S, Butkus S. What predicts re-employment after job loss for individuals with mental retardation? J Vocat Rehabil. 2006;24(3):183–9.

Dean EE, Shogren KA, Hagiwara M, Wehmeyer ML. How does employment influence health outcomes? A systematic review of the intellectual disability literature. J Vocat Rehabil. 2018;49(1):1–13.

Eggleton I, Robertson S, Ryan J, Kober R. The impact of employment on the quality of life of people with an intellectual disability. J Vocat Rehabil. 1999;13(2):95–107.

Siperstein GN, Parker RC, Drascher M. Natl Snapshot Adults Intellect Disabil Labor Force. 2013;39(3):157–65.

Vesala HT, Klem S, Ahlsten M. Kehitysvammaisten ihmisten työllisyystilanne 2013–2014 (Employment of people with intellectual disabilities 2013–2014). Kehitysvammaliiton selvityksiä 9/2015.

Emerson E, Hatton C. Residential provision for people with intellectual disabilities in England, Wales and Scotland. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 1998;11(1):1–14.

Emerson E, Hatton C, Robertson J, Roberts H, Baines S, Evison E, Glover G. People with learning disabilities in England 2010. Learning Disability Observatory: Improving health and lives; 2011.

Randell M, Cumella S. People with an intellectual disability living in an intentional community. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009;53(8):716–26.

Beyer S, Meek A, Davies A. Supported work experience and its impact on young people with intellectual disabilities, their families and employers. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil. 2016;10(3):207–20.

McKenzie K, Milton M, Smith G, Ouellette-Kuntz H. Systematic review of the prevalence and incidence of intellectual disabilities. Current trends and issues. Curr Dev Disord Rep 2016; 3: 104–115.

Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, Dua T, Saxena S. Prevalence of intellectual disability. A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(2):419–36.

Patja K, Iivanainen M, Vesala H, Oksanen H, Ruoppila I. Life expectance of people with intellectual disability. A 35-year follow-up study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2000;44(5):591–9.

Westerinen H, Kaski M, Virta L, Almqvist F, Iivanainen M. Prevalence of intellectual disability. A comprehensive study based on national registers. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2007;51(9):715–25.

Austin BS, Lee C-L. A structural equation model of vocational rehabilitation services. Predict Employ Outcomes Clients Intellect Co-occurring Psychiatr Disabil. 2014;80(8):11–20.

European Intellectual Disability Research Network. Intellectual disability in Europe. Working papers. University of Kent, Canterbury 2003.

Ratti V, Hassiotis A, Crabtree J, Deb S, Gallagher P, Unwin G. The effectiveness of person-centred planning for people with intellectual disabilities. A systematic review. Res Dev Disabil 2016; 57:63–84.

Kaehne A, Beyer S. Person-centred reviews as a mechanism for planning the post-school transition of young people with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2014;58(7):603–13.

Vornholt K, Villotti P, Muschalla B, Bauer J, Colella A, Zijlstra F. Disability and employment–overview and highlights. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2018;27(1):40–55.

Sechoaro EJ, Scrooby B, Koen DP. The effects of rehabilitation on intellectually-disabled people. A systematic review. Health SA Gesondheid. 2014;19(1):9.

Rosen M, Bussone A, Dakunchak P, Cramp J. Sheltered employment and the second generation workshop. J Rehabil. 1993;59(1):30–4.

Hsu T-H, Huang Y-J, Ososkie J. Challenges in transition from sheltered workshop to competitive employment. Perspectives of Taiwan social enterprise transition specialists. J Rehabil. 2009;75(4):19–26.

AAIDD. Intellectual disability. Definition, classification, and systems of supports. The 11th edition of the AAIDD definition manual. Washington D.C.: AAIDD, 2010.

Damianidou D, Foggett J, Arthur-Kelly M, Lyons G, Wehmeyer ML. Effectiveness of technology types in employment-related outcomes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: an extension meta-analysis. Adv Neurodev Disord. 2018;2(3):262–72.

WHO, World Health Organisation. ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, 2001.

Bauer SM, Elsaesser L-J, Arthanat S. Assistive technology device classification based upon the World Health Organization’s, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Disabil Rehabil. 2011;6(3):243–59.

Anner J, Schwegler U, Kunz R, Trezzini B, de Boer W. Evaluation of work disability and the international classification of functioning, disability and health. What to expect and what not. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):470.

Khan F, Ng L, Turner-Stokes L. Effectiveness of vocational rehabilitation intervention on the return to work and employment of persons with multiple sclerosis. Cochr Collab. 2011;12(1):1–24.

Higgins JPT, Green S, (Eds.) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012. Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470712184.fmatter/pdf.

Nevala N, Pehkonen I, Teittinen A, Vesala HT, Pörtfors P, Anttila H. Kuntoutuksen vaikuttavuus kehitysvammaisten toimintakykyyn ja työllistymiseen sekä sitä estävät ja edistävät tekijät (The effectiveness of rehabilitation on the functioning and employment of people with intellectual disabilities and barriers or facilitators: A systematic review). Järjestelmällinen kirjallisuuskatsaus. Kela, Työpapereita 133, 2018. Available: https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/230842/Tyopapereita133.pdf?sequence=l.

O’Connor D, Green S, Higgins JPT. Defining the review question and developing criteria for including studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. England: Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008. p. 83–94.

Van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, et al. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine. 2003;28(12):1290–9.

Turner-Stokes L, Nair A, Sedki I, Disler PB, Wade DT. Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for acquired brain injury in adults of working age. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3.

Khan F, Turner-Stokes L, Ng L, Kilpatrick T. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for adults with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 2.

Nevala N, Pehkonen I, Koskela I, Ruusuvuori J, Anttila H. Workplace accommodation among persons with disabilities. A systematic review of its effectiveness and barriers or facilitators. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(2):432–48.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Qualitative research checklist. Public Health Resource Unit & U.K. Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, 2017. Available: http://www.casp-uk.net/checklists.

Kärki A, Anttila H, Tasmuth T, Rautakorpi U-M. Lymphoedema therapy in breast cancer patients - a systematic review on effectiveness and survey of current practices and costs in Finland. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(6):850–9.

The Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews. Checklist for Case Reports. Joanna Briggs Institute 2016. Available: http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html.

Foley KR, Dyke P, Girdler S, Bourke J, Leonard H. Young adults with intellectual disability transitioning from school to post-school. A literature review framed within the ICF. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(20):1747–64.

Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, Prodinger B. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):574–83.

GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490–4.

Goldberg RT, McLean MM, LaVigne R, Fratolillo J, Sullivan FT. Transition of persons with developmental disability from extended sheltered employment to competitive employment. Ment Retard. 1990;28(5):299–304.

Kilsby MS, Beyer S. Enhancing self-determination in job matching in supported employment for people with learning disabilities: An intervention study. J Vocat Rehabil. 2002;17(2):125–35.

Gray BR, McDermott S, Butkus S. Effect of job coaches on employment likelihood for individuals with mental retardation. J Vocat Rehabil. 2000;14(1):5–11.

Beyer S, Kaehne A. The transition of young people with learning disabilities to employment. What works? J Dev Disabil. 2008;14(1):85–94.

Cimera RE. Does being in sheltered workshops improve the employment outcomes of supported employees with intellectual disabilities? J Vocat Rehabil. 2011;35(1):21–7.

Joshi GS, Bouck EC, Maeda Y. Exploring employment preparation and postschool outcomes for students with mild intellectual disability. Career Dev Transit Exceptional Individ. 2012;35(2):97–107.

Cimera RE, Burgess S, Bedesem PL. Does providing transition services by age 14 produce better vocational outcomes for students with intellectual disability? Res Pract Persons Severe Disabil. 2014;39(1):47–54.

Arvidsson J, Widén S, Staland-Nyman C, Tideman M. Post-school destination. A study of women and men with intellectual disability and the gender-segregated Swedish labor market. J Polic Pract Intellect Disabil. 2016;13(3):217–26.

Bouck EC, Chamberlain C. Postschool services and postschool outcomes for individuals with mild intellectual disability. Career Dev Transit Exceptional Individ. 2017;40(4):215–24.

Sannicandro T, Parish SL, Fournier S, Mitra M, Paiewonsky M. Employment, income, and SSI effects of postsecondary education for people with intellectual disability. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018;123(5):412–25.

Hagner D, Davies T. Doing my own thing. Supported self-employment for individuals with cognitive disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2002;17(2):65–74.

Fasching H. Compulsory school is over and now? Vocational experiences of women with intellectual disability. Creat Educ. 2014;5(10):743–51.

Christensen JJ, Richardson K. Project SEARCH workshop to work: participant reflections on the journey through career discovery. J Vocat Rehabil. 2017;46(3):341–54.

Alborno N, Gaad E. Employment of young adults with disabilities in Dubai. A case study. J Polic Pract Intellect Disabil. 2012;9(2):103–11.

Devlieger PJ, Trach JS. Mediation as a transition process. The impact on postschool employment outcomes. Exceptional Child. 1999;65(4):507–23.

Donelly M, Hillman A, Stancliffe RJ, Knox M, Whitaker L, Parmenter TR. The role of informal networks in providing effective work opportunities for people with an intellectual disability. Work. 2010;36(2):227–37.

Winsor JE, Butterworth J, Boone J. Jobs by 21 partnership project. Impact of cross-system collaboration on employment outcomes of young adults with developmental disabilities. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;49(4):274–84.

Grossi TA, Kimball JW, Heward WL. What did you say? Using review of tape-recorded interactions to increase social acknowledgments by trainees in a community-based vocational program. Res Dev Disabil. 1994;15(6):457–72.

Wehman P, Gibson K, Brooke V, Unger D. Transition from school to competitive employment. Illustrations of competence for two young women with severe mental retardation. Focus Autism Dev Disabil. 1998;13(3):130–43.

Aspinall A. How can assistive technology and telecare support the independence and employment prospects for adults with learning disabilities? J Assist Technol. 2007;1(2):43–8.

Jarhag S, Nilsson G, Werning M. Disabled persons and the labor market in Sweden. Soc Work Public Health. 2009;24(3):255–72.

Ham W, McDonough J, Molinelli A, Schall C, Wehman P. Employment supports for young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Two case studies. J Vocat Rehabil. 2014;40(2):117–24.

Renzaglia P, Wheeler JJ, Hanson HB, Miller SR. The use of extended follow-along procedures in a supported employment setting. Education and Training in Mental Retardation 1991; March:64–69.

Simmons TJ, Flexer RW. Community based job training for persons with mental retardation. An acquisition and performance replication. Educ Train Mental Retard. 1992;27(3):261–72.

Kemp DC, Carr EG. Reduction of severe problem behavior in community employment using an hypothesis-driven multicomponent intervention approach. J Am Soc Hypertens. 1995;20(4):229–47.

Taber TA, Alberto PA, Fredrick LD. Use of self-operated auditory prompts by workers with moderate mental retardation to transition independently through vocational tasks. Res Dev Disabil. 1998;19(4):327–45.

Furniss F, Ward A, Lancioni G, Rocha N, Cunha B, Seedhouse P, Morato P, Waddell N. A palmtop-based job aid for workers with severe intellectual disabilities. Technol Disabil. 1999;10:53–67.

McGlashing-Johnson J, Agran M, Sitlington P, Cavin M, Wehmeyer M. Enhancing the job performance of youth with moderate to severe cognitive disabilities using the self-determined learning model of instruction. Res Pract Persons Severe Disabil. 2003;28(4):194–204.

Carson KD, Gast DL, Ayres KM. Effects of a photo activity schedule book on independent task changes by students with intellectual disabilities in community and school job sites. Eur J Special Needs Educ. 2008;23(3):269–79.

Bennett K, Brady MP, Scott J, Dukes C, Frain M. The effects of covert audio coaching on the job performance of supported employees. Focus Autism Dev Disabil. 2010;25(3):173–85.

West EA, Patton HA. Positive behaviour support and supported employment for adults with severe disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;35(2):104–11.

Chang YJ, Wang TY, Chen YR. A location-based prompting system to transition autonomously through vocational tasks for individuals with cognitive impairments. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(6):2669–73.

Devlin P. Enhancing job performance. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;49(4):221–32.

Allen KD, Burke RV, Howard MR, Wallace DP, Bowen SL. Use of audio cuing to expand employment opportunities for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(11):2410–9.

Dotson WH, Richman DM, Abby L, Thompson S, Plotner A. Teaching skills related to self-employment to adults with developmental disabilities: an analog analysis. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(8):2336–50.

McMahon D, Cihak DF, Wright R. Augmented reality as a navigation tool to employment opportunities for postsecondary education students with intellectual disabilities and autism. J Res Technol Educ. 2015;47(3):157–72.

Gilson CB, Carter EW. Promoting Social Interactions and Job Independence for College Students with Autism or Intellectual Disability: a Pilot Study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(11):3583–96.

Van Laarhoven T, Carreon A, Bonneau W, Lagerhausen A. Comparing mobile technologies for teaching vocational skills to individuals with autism spectrum disorders and/or intellectual disabilities using universally-designed prompting systems. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(7):2516–29.

Mank D, Cioffi A, Yovanoff P. Supported employment outcomes across a decade. Is there evidence of improvement in the quality of implementation? Ment Retard. 2003;41(3):188–97.

Ellenkamp JJ, Brouwers EP, Embregts PJ, Joosen MC, van Weeghel J. Work environment - related factors in obtaining and maintaining work in a competitive employment setting for employees with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(1):56–69.

A concept paper on digitization, employability and inclusiveness. The role of Europe. DG communications networks. Content & Technology (CONNECT). European Comission, 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/document.cfm?doc_id=44515

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Researcher Simo Klem for his help in reviewing the titles, and Alice Lehtinen for editing the language of the manuscript. Financial support was provided by The Social Insurance Institution of Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NN: study plan and design, conceptual development of the variables, data collection, review of the titles and abstracts, quality assessment of the quantitative and case studies, analysis and interpretation of the data, draft and critical revision of the manuscript. IP: study plan and design, conceptual development of the variables, data collection, review of the titles and abstracts, quality assessment of the quantitative and case studies, analysis and interpretation of the data, draft and critical revision of the manuscript. AT: conceptual development of the variables, data collection, review of the titles and abstracts, quality assessment of the qualitative studies, analysis and interpretation of the data, draft and critical revision of the manuscript. HTV: conceptual development of the variables, data collection, review of the titles and abstracts, quality assessment of the qualitative studies, analysis and interpretation of the data, draft and critical revision of the manuscript. PP: performance of the searches in 12 databases and two search engines, definition of the search terms with the research group, management of the articles in Refworks, management of full details of the search strategy, and critical revision of the manuscript. HA: conceptual development of the variables and the ICF model, review of the titles and abstracts, quality assessment of the qualitative studies, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Nina Nevala, Irmeli Pehkonen, Antti Teittinen, Hannu T. Vesala, Pia Pörtfors, and Heidi Anttila declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nevala, N., Pehkonen, I., Teittinen, A. et al. The Effectiveness of Rehabilitation Interventions on the Employment and Functioning of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review. J Occup Rehabil 29, 773–802 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09837-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09837-2