Abstract

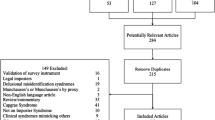

Purpose To determine whether the delayed recovery often observed in simple musculoskeletal injuries occurring at work is related to poor workplace and home social support. Method A four question psychosocial screening tool called the “How are you coping gauge?” (HCG) was developed. This tool was implemented as part of the initial assessment for all new musculoskeletal workplace injuries. Participants were excluded if they did not meet the strict criteria used to classify a musculoskeletal injury as simple. The HCG score was then compared to the participant’s number of days until return to full capacity (DTFC). It was hypothesised that those workers indicating a poorer level of workplace and home support would take longer time to return to full capacity. Results A sample of 254 participants (316 excluded) were included in analysis. Significant correlation (p < 0.001) was observed between HCG scores for self-reported work and home support and DTFC thereby confirming the hypothesis. Path analysis found workplace support to be a significant moderate-to-strong predictor of DTFC (−0.46). Conclusion A correlation was observed between delayed workplace injury recovery and poor perceived workplace social support. The HCG may be an effective tool for identifying these factors in musculoskeletal workplace injuries of a minor pathophysiological nature. There may be merit in tailoring injury rehabilitation towards addressing psychosocial factors early in the injury recovery process to assist with a more expedient return to full work capacity following simple acute musculoskeletal injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bailey TS, Dollard MF, McLinton SS, Richards, PAM. Psychosocial safety climate, psychosocial and physical factors in the aetiology of musculoskeletal disorder symptoms and workplace injury compensation claims. Work Stress. 2015;29(2):190–211.

Heymans MW, de Vet HCW, Knol DL, Bongers PM, Koes BW, Mechelen WV. Workers’ beliefs and expectations affect return to work over 12 months. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(4):685–695.

Dunstan DA, Covic T, Tyson GA. What leads to the expectation to return to work? insights from a theory of planned behavior (TPB) model of future work outcomes. Work. 2013;46(1):25–37.

Cole DC, Mondloch MV, Hogg-Johnson S. Listening to injured workers: how recovery expectations predict outcomes—a prospective study. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166(6):749–754.

Godges JJ, Anger MA, Zimmerman G, Delitto A. Effects of education on return-to-work status for people with fear-avoidance beliefs and acute low back pain. Phys Ther. 2008;88(2):231–239.

Lysaght RM, Larmour-Trode S. An exploration of social support as a factor in the return-to-work process. Work. 2008;30(3):255–266.

Hoogendoorn WE, van Poppel MN, Bongers PM, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Systematic review of psychosocial factors at work and private life as risk factors for back pain. Spine. 2000;25(16):2114–2125.

Crisco JJ, Jokl P, Heinen GT, Connell MD, Panjabi MM. A muscle contusion injury model: biomechanics, physiology, and histology. Am J Sport Med. 1994;22(5):702–710.

Askling C, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Type of acute hamstring strain affects flexibility, strength, and time to return to pre-injury level. Brit J Sport Med. 2006;40(1):40–44.

Sullivan M, Feuerstein M, Gatchel R, Linton S, Pransky G. Integrating psychosocial and behavioral interventions to achieve optimal rehabilitation outcomes. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):475–489.

Schultz IZ, Crook J, Berkowitz J, Milner R, Meloche GR. Predicting return to work after low back injury using the psychosocial risk for occupational disability instrument: a validation study. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(11):365–376.

Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):1–17.

Wall C, Ogloff JP, Morrissey S. The psychology of injured workers: health and cost of vocational rehabilitation. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(4):513–528.

Grimmer-Somers K, Vipond N, Kumar S, Hall G. A review and critique of assessment instruments for patients with persistent pain. Journal of pain research. 2009;2(2):21–47.

Jette DU, Halbert J, Iverson C, Micheli E, Shah P. Use of standardized outcome measures in physical therapist practice: perceptions and applications. Phys Ther. 2009;89(2):125–135.

WorkSafe Victoria. Clinical framework for the delivery of health services. Melbourne: WorkSafe Victoria; 2012. p. 24.

Linton SJ, Halldén K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain. 1998;14(3):209–215.

Dunstan DA, Covic T, Tyson GA, Lennie IG. Does the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire predict outcomes following a work-related compensable injury? Int J Rehabil Res. 2005;28(4):369–370.

Arnetz BB, Sjögren B, Rydéhn B, Meisel R. Early workplace intervention for employees with musculoskeletal-related absenteeism: a prospective controlled intervention study. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(5):499–506.

Franche RL, Severin CN, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Vidmar M, Lee H. The impact of early workplace-based return-to-work strategies on work absence duration: a 6-month longitudinal study following an occupational musculoskeletal injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(9):960–974.

Linton SJ, Nicholas M, MacDonald S. Development of a short form of the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. SPINE. 2011;36(22):1891–1895.

Duncan EA, Murray J. The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):96.

Järvinen TAH, Järvinen TLN, Kääriäinen M, Kalimo H, Järvinen M. Muscle injuries: biology and treatment. Am J Sport Med. 2005;33(5):745–764.

Shain M, Kramer DM. Health promotion in the workplace: framing the concept; reviewing the evidence. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(7):643–648.

MacEachen E, Kosny A, Ferrier S, Chambers L. The “toxic dose” of system problems: why some injured workers don’t return to work as expected. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(3):349–366.

Hockings RL, McAuley JH, Maher CG. A systematic review of the predictive ability of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. SPINE. 2008;33(15):E494–E500.

Minden P. The importance of words: suggesting comfort rather than pain. Holist Nurs Pract. 2005;19(6):267–271.

Eck J, Richter M, Straube T, Miltner WHR, Weiss T. Affective brain regions are activated during the processing of pain-related words in migraine patients. PAIN. 2011;152(5):1104–1113.

Richter M, Eck J, Straube T, Litner WHR, Weiss T. Do words hurt? Brain activation during the processing of pain-related words. PAIN. 2010;148(2):198–205.

Hertling D, Kessler RM. Management of common musculoskeletal disorders: physical therapy principles and methods. 4th ed. Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

Dahlgren LA, Mohammed HO, Nixon AJ. Temporal expression of growth factors and matrix molecules in healing tendon lesions. J Orthopaed Res. 2005;23(1):84–92.

Sharma P, Maffulli N. Basic biology of tendon injury and healing. Surg. 2005;3(5):309–316.

Schultz G, Mozingo D, Romanelli M, Claxton K. Wound healing and TIME; new concepts and scientific applications. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13(s4):S1–S11.

Velnar T, Bailey T, Smrkolj V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1528–1542.

Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S2–S15.

Zatzick D, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Wang J, Fan MY, Joesch J, Mackenzie E. A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):429–423.

Safe Work Australia. Australian workers’ compensation statistics 2012-13. Canberra: Safe Work Australia; 2013.

Arbuckle JL. IBM SPSS AMOS 21 user’s guide. Armonk: IBM Corporation; 2012.

Cohen J. Statistical power for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1998.

Taris TW, Kompier M. Challenges in longitudinal designs in occupational health psychology. Scand J Work Environ Health 2003;29(1):1–4.

Karademas EC. Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: the mediating role of optimism. Pers Indiv Differ. 2006;40(6):1281–1290.

Return to Work Act 2014 (SA).

ReturnToWorkSA. Physiotherapy fee schedule and policy. Adelaide (AU): ReturnToWorkSA; 2016. p. 26.

Smith GS, Huang YH, Ho M, Chen PY. The relationship between safety climate and injury rates across industries: the need to adjust for injury hazards. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38(3):556–562.

Gillen M, Yen IH, Trupin L, Swig L, Rugulies R, Mullen K, Font A, Burian D, Ryan G, Janowitz I. The association of socioeconomic status and psychosocial and physical workplace factors with musculoskeletal injury in hospital workers. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50(4):245–260.

Franche R-L, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(4):233–256.

Shamian J, O’Brien-Pallas L, Thomson D, Alksnis C, Steven Kerr M. Nurse absenteeism, stress and workplace injury: what are the contributing factors and what can/should be done about it? Int J Sociol Soc Policy. 2003;23(8/9):81–103.

Rogers E, Wiatrowksi WJ. Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities among older workers. Mon Labor Rev. 2005;128(10):24–30.

Hermes GL, Rosenthal L, Montag A, McClintock MK. Social isolation and the inflammatory response: sex differences in the enduring effects of a prior stressor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290(2):R273–R82.

Detillion CE, Craft TKS, Glasper ER, Prendergast BJ, DeVries AC. Social facilitation of wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2004;29(8):1004–1011.

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL. Enhancing the interpretation of significant findings: the role of mixed methods research. The Qualitative Report. 2004;9(4):770–792.

Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educational researcher. 2004;33(7):14–26.

Kirsh B, Slack T, King CA. The nature and impact of stigma towards injured workers. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(2):143–154.

Beardwood BA, Kirsh B, Clark NJ. Victims twice over: perceptions and experiences of injured workers. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(1):30–48.

Soklaridis S, Ammendolia C, Cassidy D. Looking upstream to understand low back pain and return to work: psychosocial factors as the product of system issues. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(9):1557–1566.

Chan ANW. Social support for improved work integration: perspectives from Canadian social purpose enterprises. Soc Enterp J. 2015;11(1):47–68.

Funding

All authors declare that no funding was obtained in formation of this body of work.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Conflict of interest

Author Sareen McLinton, Sarven Savia McLinton and Martin van der Linden declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was submitted to the University of South Australia for ethics review prior to commencement. Our application was reviewed and was considered exempt based on its study design. Therefore approval was given to undertake data collection.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McLinton, S., McLinton, S.S. & van der Linden, M. Psychosocial Factors Impacting Workplace Injury Rehabilitation: Evaluation of a Concise Screening Tool. J Occup Rehabil 28, 121–129 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9701-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9701-6