Abstract

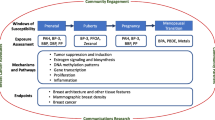

Breast cancer risk has both heritable and environment/lifestyle components. The heritable component is a small contribution (5–27 %), leaving the majority of risk to environment (e.g., applied chemicals, food residues, occupational hazards, pharmaceuticals, stress) and lifestyle (e.g., physical activity, cosmetics, water source, alcohol, smoking). However, these factors are not well-defined, primarily due to the enormous number of factors to be considered. In both humans and rodent models, environmental factors that act as endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) have been shown to disrupt normal mammary development and lead to adverse lifelong consequences, especially when exposures occur during early life. EDCs can act directly or indirectly on mammary tissue to increase sensitivity to chemical carcinogens or enhance development of hyperplasia, beaded ducts, or tumors. Protective effects have also been reported. The mechanisms for these changes are not well understood. Environmental agents may also act as carcinogens in adult rodent models, directly causing or promoting tumor development, typically in more than one organ. Many of the environmental agents that act as EDCs and are known to affect the breast are discussed. Understanding the mechanism(s) of action for these compounds will be critical to prevent their effects on the breast in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for disease contral and prevention. Cancer among women. 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/women.htm. 2012.

American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Overview. 2012. http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/BreastCancer/OverviewGuide/breast-cancer-overview-key-statistics.

American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts and figures 2011–2012. 2011.

Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer–analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(2):78–85. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007133430201.

Buttke DE, Sircar K, Martin C. Exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and age of menarche in adolescent girls in NHANES (2003–2008). Environ Heal Perspect. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104748.

Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon J-P, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocrine Rev. 2009;30(4):293–342. doi:10.1210/er.2009-0002.

US Environmental Protection Agency. Endocrine Disruptors Research. 2012. http://www.epa.gov/endocrine/#eds.

Nelson CM, Bissell MJ. Of extracellular matrix, scaffolds, and signaling: tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:287–309. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104315.

US Environmental Protection Agency. TSCA Chemical Substance Inventory. 2011. http://www.epa.gov/oppt/existingchemicals/pubs/tscainventory/index.html.

Vineis P, Schatzkin A, Potter JD. Models of carcinogenesis: an overview. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(10):1703–9. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgq087.

Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. The tissue organization field theory of cancer: a testable replacement for the somatic mutation theory. BioEssays: News Rev Mol Cell Dev Biol. 2011;33(5):332–40. doi:10.1002/bies.201100025.

National Toxicology Program. Nominations to the Testing Program. 2012. http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/?objectid=25BC6AF8-BDB7-CEBA-F18554656CC4FCD9.

National Toxicology Program. Report on Carcinogens, 12th, http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/roc/twelfth/roc12.pdf.

Diethylstilbestrol [database on the Internet]. Available from: http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100A/mono100A-16.pdf. Accessed.

Knudson AG. Hereditary cancer: two hits revisited. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1996;122(3):135–40.

Markey CM, Luque EH, Munoz De Toro M, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. In utero exposure to bisphenol A alters the development and tissue organization of the mouse mammary gland. Biol Reprod. 2001;65(4):1215–23.

Rudel RA, Fenton SE, Ackerman JM, Euling SY, Makris SL. Environmental exposures and mammary gland development: state of the science, public health implications, and research recommendations. Environ Heal Perspect. 2011;119(8):1053–61. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002864.

National Cancer Institute. The Cost of Care. 2011. http://www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/servingpeople/cancer-statistics/costofcancer. 2012.

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–502. doi:10.1001/jama.295.21.2492.

Eroles P, Bosch A, Perez-Fidalgo JA, Lluch A. Molecular biology in breast cancer: intrinsic subtypes and signaling pathways. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(6):698–707. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.11.005.

Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, Ibrahim N, Cristofanilli M, Anderson K, et al. Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to preoperative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5678–85. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2421.

Desmedt C, Haibe-Kains B, Wirapati P, Buyse M, Larsimont D, Bontempi G, et al. Biological processes associated with breast cancer clinical outcome depend on the molecular subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(16):5158–65. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4756.

Fenton SE. Endocrine-disrupting compounds and mammary gland development: early exposure and later life consequences. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6 Suppl):S18–24. doi:10.1210/en.2005-1131.

Monosson E, Kelce WR, Lambright C, Ostby J, Gray Jr LE. Peripubertal exposure to the antiandrogenic fungicide, vinclozolin, delays puberty, inhibits the development of androgen-dependent tissues, and alters androgen receptor function in the male rat. Toxicol Ind Health. 1999;15(1–2):65–79.

Buckley J, Willingham E, Agras K, Baskin LS. Embryonic exposure to the fungicide vinclozolin causes virilization of females and alteration of progesterone receptor expression in vivo: an experimental study in mice. Environ Health. 2006;5:4. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-5-4.

Gray LE, Ostby J, Furr J, Wolf CJ, Lambright C, Parks L, et al. Effects of environmental antiandrogens on reproductive development in experimental animals. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7(3):248–64.

Rothschild TC, Boylan ES, Calhoon RE, Vonderhaar BK. Transplacental effects of diethylstilbestrol on mammary development and tumorigenesis in female ACI rats. Cancer Res. 1987;47(16):4508–16.

Kawaguchi H, Umekita Y, Souda M, Gejima K, Kawashima H, Yoshikawa T, et al. Effects of neonatally administered high-dose diethylstilbestrol on the induction of mammary tumors induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene in female rats. Vet Pathol. 2009;46(1):142–50. doi:10.1354/vp.46-1-142.

Muto T, Wakui S, Imano N, Nakaaki K, Hano H, Furusato K, et al. In utero and lactational exposure of 3,3′, 4,4′, 5- pentachlorobiphenyl modulate dimenthlben[a]anthracene-induced rat mammary carcinogenesis. J Toxicologica Pathol. 2001;14:213–24.

Rayner JL, Enoch RR, Fenton SE. Adverse effects of prenatal exposure to atrazine during a critical period of mammary gland growth. Toxicol Sci. 2005;87(1):255–66. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi213.

White SS, Fenton SE, Hines EP. Endocrine disrupting properties of perfluorooctanoic acid. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.03.011.

Restum JC, Bursian SJ, Giesy JP, Render JA, Helferich WG, Shipp EB, et al. Multigenerational study of the effects of consumption of PCB-contaminated carp from Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron, on mink. 1. Effects on mink reproduction, kit growth and survival, and selected biological parameters. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1998;54(5):343–75.

Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Knittel JG, Yan L, Rueden CT, et al. Collagen density promotes mammary tumor initiation and progression. BMC Med. 2008;6:11. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-6-11.

Maffini MV, Soto AM, Calabro JM, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C. The stroma as a crucial target in rat mammary gland carcinogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 8):1495–502. doi:10.1242/jcs.01000.

White SE, Kato K, Jia LT, Basden BJ, Calafat AM, Hines EP, et al. Effect of perfluorooctanoic acid on mouse mammary gland development and differention resulting from cross-foster and restricted gestational exposure. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;27:289–98. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.11.054.

White SE, Calafat AM, Kuklenyik Z, Villanueva L, Zehr RD, Helfant L, et al. Gestational PFOA exposure of mice is associated with altered mammary gland development in dams and female offspring. Toxicol Sci. 2007;96(1):133–44. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfl177.

Fertuck KC, Kumar S, Sikka HC, Matthews JB, Zacharewski TR. Interaction of PAH-related compounds with the alpha and beta isoforms of the estrogen receptor. Toxicol Lett. 2001;121(3):167–77.

Archer FL, Orlando R. Morphology, natural history, and enzyme patterns in mammary tumors of the rat induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene. Cancer Res. 1968;28:217–23.

Ito N, Hasegawa R, Sano M, Tamano S, Esumi H, Takayama S, et al. A new colon and mammary carcinogen in cooked food, 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP). Carcinogenesis. 1991;12(8):1503–6.

Lauber SN, Ali S, Gooderham NJ. The cooked food derived carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b] pyridine is a potent oestrogen: a mechanistic basis for its tissue-specific carcinogenicity. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(12):2509–17.

Gooderham NJ, Zhu H, Lauber S, Boyce A, Creton S. Molecular and genetic toxicology of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP). Mutat Res. 2002;507:91–9.

Lightfoot TJ, Coxhead JM, Cupid BC, Nicholson S, Garner RC. Analysis of DNA adducts by accelerator mass spectrometry in human breast tissue after administration of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and benzo[a]pyrene. Mutat Res. 2000;472(1–2):119–27.

Zheng W, Gustafson DR, Sinha R, Cerhan JR, Moore D, Hong CP, et al. Well-done meat intake and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Canc Inst. 1998;90(22):1724–9.

Pottenger LH, Domoradzki JY, Markham DA, Hansen SC, Cagen SZ, Waechter Jr JM. The relative bioavailability and metabolism of bisphenol A in rats is dependent upon the route of administration. Toxicol Sci. 2000;54(1):3–18.

Völkel W, Colnot T, Csanady GA, Filser JG, Dekant W. Metabolism and kinetics of bisphenol a in humans at low doses following oral administration. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15(10):1281–7.

Trasande L, Attina TM, Blustein J. Association between urinary bisphenol A concentration and obesity prevalence in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2012;308(11):1113–21. doi:10.1001/2012.jama.11461.

Vandenberg LN, Maffini MV, Schaeberle CM, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C, Rubin BS, et al. Perinatal exposure to the xenoestrogen bisphenol-A induces mammary intraductal hyperplasias in adult CD-1 mice. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;26(3–4):210–9. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.09.015.

Naciff JM, Jump ML, Torontali SM, Carr GJ, Tiesman JP, Overmann GJ, et al. Gene expression profile induced by 17alpha-ethynyl estradiol, bisphenol A, and genistein in the developing female reproductive system of the rat. Toxicol Sci. 2002;68(1):184–99.

Thayer KA, Belcher S. Mechanisms of action of bisphenol A and other biochemical/molecular interactions, http://www.who.int/foodsafety/chem/chemicals/5_biological_activities_of_bpa.pdf.

Bhattacharya P, Keating AF. Impact of environmental exposures on ovarian function and role of xenobiotic metabolism during ovotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;261(3):227–35. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.009.

Quignot N, Arnaud M, Robidel F, Lecomte A, Tournier M, Cren-Olive C, et al. Characterization of endocrine-disrupting chemicals based on hormonal balance disruption in male and female adult rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33(3):339–52. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.01.004.

Richter CA, Birnbaum LS, Farabollini F, Newbold RR, Rubin BS, Talsness CE, et al. In vivo effects of bisphenol A in laboratory rodent studies. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24(2):199–224. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.06.004.

Munoz-de-Toro M, Markey CM, Wadia PR, Luque EH, Rubin BS, Sonnenschein C, et al. Perinatal exposure to bisphenol-A alters peripubertal mammary gland development in mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146(9):4138–47. doi:10.1210/en.2005-0340.

Mori T, Bern HA, Mills KT, Young PN. Long-term effects of neonatal steroid exposure on mammary gland development and tumorigenesis in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57(5):1057–62.

Lamartiniere CA, Jenkins S, Betancourt AM, Wang J, Russo J. Exposure to the endocrine disruptor bisphenol A alters susceptibility for mammary cancer. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2011;5(2):45–52. doi:10.1515/HMBCI.2010.075.

Tharp AP, Maffini MV, Hunt PA, VandeVoort CA, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Bisphenol A alters the development of the rhesus monkey mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(21):8190–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120488109.

Jenkins S, Raghuraman N, Eltoum I, Carpenter M, Russo J, Lamartiniere CA. Oral exposure to bisphenol a increases dimethylbenzanthracene-induced mammary cancer in rats. Environ Heal Perspect. 2009;117(6):910–5. doi:10.1289/ehp.11751.

Betancourt AM, Eltoum IA, Desmond RA, Russo J, Lamartiniere CA. In utero exposure to bisphenol A shifts the window of susceptibility for mammary carcinogenesis in the rat. Environ Heal Perspect. 2010;118(11):1614–9. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002148.

Doherty LF, Bromer JG, Zhou Y, Aldad TS, Taylor HS. In utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) or bisphenol-A (BPA) increases EZH2 expression in the mammary gland: an epigenetic mechanism linking endocrine disruptors to breast cancer. Horm Cancer. 2010;1(3):146–55. doi:10.1007/s12672-010-0015-9.

Jenkins S, Wang J, Eltoum I, Desmond R, Lamartiniere CA. Chronic oral exposure to bisphenol A results in a nonmonotonic dose response in mammary carcinogenesis and metastasis in MMTV-erbB2 mice. Environ Heal Perspect. 2011;119(11):1604–9. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103850.

Ogura I, Masunaga S, Nakanishi J. Quantitative source identification of dioxin-like PCBs in Yokohama, Japan, by temperature dependence of their atmospheric concentrations. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38(12):3279–85.

Safe SH. Modulation of gene expression and endocrine response pathways by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related compounds. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;67(2):247–81.

Safe SH. Hazard and risk assessment of chemical mixtures using the toxic equivalency factor approach. Environ Heal Perspect. 1998;106 Suppl 4:1051–8.

Chaffin CL, Peterson RE, Hutz RJ. In utero and lactational exposure of female Holtzman rats to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin: modulation of the estrogen signal. Biol Reprod. 1996;55(1):62–7.

Fenton SE, Hamm JT, Birnbaum LS, Youngblood GL. Persistent abnormalities in the rat mammary gland following gestational and lactational exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Toxicol Sci. 2002;67(63):63–74.

Brown NM, Manzolillo PA, Zhang JX, Wang J, Lamartiniere CA. Prenatal TCDD and predisposition to mammary cancer in the rat. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(9):1623–9.

Franczak A, Nynca A, Valdez KE, Mizinga KM, Petroff BK. Effects of acute and chronic exposure to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on the transition to reproductive senescence in female Sprague–Dawley rats. Biol Reprod. 2006;74(1):125–30. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.105.044396.

Brown NM, Lamartiniere CA. Xenoestrogens alter mammary gland differentiation and cell proliferation in the rat. Environ Heal Perspect. 1995;103(7–8):708–13.

Gray Jr LE, Kelce WR, Monosson E, Ostby JS, Birnbaum LS. Exposure to TCDD during development permanently alters reproductive function in male Long Evans rats and hamsters: reduced ejaculated and epididymal sperm numbers and sex accessory gland weights in offspring with normal androgenic status. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;131(1):108–18. doi:10.1006/taap.1995.1052.

Chan MY, Huang H, Leung LK. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-para-dioxin increases aromatase (CYP19) mRNA stability in MCF-7 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;317(1–2):8–13. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.012.

Warner M, Eskenazi B, Mocarelli P, Gerthoux PM, Samuels S, Needham L, et al. Serum dioxin concentrations and breast cancer risk in the Seveso Women’s Health Study. Environ Heal Perspect. 2002;110(7):625–8.

Boffetta P, Mundt KA, Adami HO, Cole P, Mandel JS. TCDD and cancer: a critical review of epidemiologic studies. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2011;41(7):622–36. doi:10.3109/10408444.2011.560141.

Manuwald U, Velasco Garrido M, Berger J, Manz A, Baur X. Mortality study of chemical workers exposed to dioxins: follow-up 23 years after chemical plant closure. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(9):636–42. doi:10.1136/oemed-2012-100682.

Van den Berg M, Birnbaum LS, Denison M, De Vito M, Farland W, Feeley M, et al. The 2005 World Health Organization reevaluation of human and Mammalian toxic equivalency factors for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol Sci. 2006;93(2):223–41. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfl055.

Muto T, Wakui S, Imano N, Nakaaki K, Takahashi H, Hano H, et al. Mammary gland differentiation in female rats after prenatal exposure to 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl. Toxicology. 2002;177(2–3):197–205.

Oenga GN, Spink DC, Carpenter DO. TCDD and PCBs inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2004;18(6):811–9. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2004.04.004.

Brody JG, Moysich KB, Humblet O, Attfield KR, Beehler GP, Rudel RA. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2007;109(12 Suppl):2667–711. doi:10.1002/cncr.22655.

LeBlanc GA. Endocrine system. In: Hodgson E, editor. A textbook of modern toxicology. 3rd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. p. 299–315.

Registry AfTSaD, Toxicological profile for DDT, DDE, and DDD, http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp35.pdf.

Johnson NA, Ho A, Cline JM, Hughes CL, Foster WG, Davis VL. Accelerated mammary tumor onset in a HER2/Neu mouse model exposed to DDT metabolites locally delivered to the mammary gland. Environ Heal Perspect. 2012;120(8):1170–6. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104327.

Robison AK, Sirbasku DA, Stancel GM. DDT supports the growth of an estrogen-responsive tumor. Toxicol Lett. 1985;27(1–3):109–13.

Cohn BA, Wolff MS, Cirillo PM, Sholtz RI. DDT and breast cancer in young women: new data on the significance of age at exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(10):1406–14. doi:10.1289/ehp.10260.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Toxicological Profile for Atrazine, http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp153.pdf.

Rayner JL, Fenton SE. In: Russo J, editor. Atrazine: an environmental endocrine disruptor that alters mammary gland development and tumor susceptibility environment and breast cancer. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 167–83.

US Environmental Protection Agency. Atrazine: hazard and dose–response assessment and characterization federal insecticide F, and Rodenticide Act Science Advisory Report, http://www.epa.gov/scipoly/sap/meetings/2000/june27/finalatrazine.pdf.

Foradori CD, Hinds LR, Hanneman WH, Handa RJ. Effects of atrazine and its withdrawal on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuroendocrine function in the adult female Wistar rat. Biol Reprod. 2009;81(6):1099–105. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.109.077453.

Stoker TE, Laws SC, Guidici DL, Cooper RL. The effect of atrazine on puberty in male wistar rats: an evaluation in the protocol for the assessment of pubertal development and thyroid function. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58(1):50–9.

Stanko JP, Enoch RR, Rayner JL, Davis CC, Wolf DC, Malarkey DE, et al. Effects of prenatal exposure to a low dose atrazine metabolite mixture on pubertal timing and prostate development of male Long-Evans rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30(4):540–9. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.07.006.

Enoch RR, Stanko JP, Greiner SN, Youngblood GL, Rayner JL, Fenton SE. Mammary gland development as a sensitive end point after acute prenatal exposure to an atrazine metabolite mixture in female Long-Evans rats. Environ Heal Perspect. 2007;115(4):541–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.9612.

Gammon DW, Aldous CN, Carr Jr WC, Sanborn JR, Pfeifer KF. A risk assessment of atrazine use in California: human health and ecological aspects. Pest Manag Sci. 2005;61(4):331–55. doi:10.1002/ps.1000.

Stevens JT, Breckenridge CB, Wetzel L. A risk characterization for atrazine: oncogenicity profile. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1999;56(2):69–109.

Eldridge JC, Wetzel LT, Stevens JT, Simpkins JW. The mammary tumor response in triazine-treated female rats: a threshold-mediated interaction with strain and species-specific reproductive senescence. Steroids. 1999;64(9):672–8.

Fukamachi K, Han BS, Kim CK, Takasuka N, Matsuoka Y, Matsuda E, et al. Possible enhancing effects of atrazine and nonylphenol on 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary tumor development in human c-Ha-ras proto-oncogene transgenic rats. Cancer Sci. 2004;95(5):404–10.

US Environmental Protection Agency, RED Facts: Vinclozolin http://www.epa.gov/oppsrrd1/REDs/factsheets/2740fact.pdf.

Wickerham EL, Lozoff B, Shao J, Kaciroti N, Xia Y, Meeker JD. Reduced birth weight in relation to pesticide mixtures detected in cord blood of full-term infants. Environ Int. 2012;47:80–5. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2012.06.007.

Molina-Molina JM, Hillenweck A, Jouanin I, Zalko D, Cravedi JP, Fernandez MF, et al. Steroid receptor profiling of vinclozolin and its primary metabolites. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216(1):44–54. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2006.04.005.

Gray Jr LE, Ostby JS, Kelce WR. Developmental effects of an environmental antiandrogen: the fungicide vinclozolin alters sex differentiation of the male rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1994;129(1):46–52. doi:10.1006/taap.1994.1227.

Kelce WR, Monosson E, Gamcsik MP, Laws SC, Gray Jr LE. Environmental hormone disruptors: evidence that vinclozolin developmental toxicity is mediated by antiandrogenic metabolites. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1994;126(2):276–85. doi:10.1006/taap.1994.1117.

Anway MD, Leathers C, Skinner MK. Endocrine disruptor vinclozolin induced epigenetic transgenerational adult-onset disease. Endocrinology. 2006;147(12):5515–23.

El Sheikh Saad H, Meduri G, Phrakonkham P, Berges R, Vacher S, Djallali M, et al. Abnormal peripubertal development of the rat mammary gland following exposure in utero and during lactation to a mixture of genistein and the food contaminant vinclozolin. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;32(1):15–25. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.03.001.

Ozen S, Darcan S, Bayindir P, Karasulu E, Simsek DG, Gurler T. Effects of pesticides used in agriculture on the development of precocious puberty. Environ Monit Assess. 2012;184(7):4223–32. doi:10.1007/s10661-011-2257-6.

Kamrin MA. Phthalate risks, phthalate regulation, and public health: a review. J Toxicol Environ Health Part B, Crit Rev. 2009;12(2):157–74. doi:10.1080/10937400902729226.

Swan SH, Main KM, Liu F, Stewart SL, Kruse RL, Calafat AM, et al. Decrease in anogenital distance among male infants with prenatal phthalate exposure. Environ Heal Perspect. 2005;113(8):1056–61.

Rider CV, Wilson VS, Howdeshell KL, Hotchkiss AK, Furr JR, Lambright CR, et al. Cumulative effects of in utero administration of mixtures of “antiandrogens” on male rat reproductive development. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37(1):100–13. doi:10.1177/0192623308329478.

Mylchreest E, Cattley RC, Foster PM. Male reproductive tract malformations in rats following gestational and lactational exposure to Di(n-butyl) phthalate: an antiandrogenic mechanism? Toxicol Sci. 1998;43(1):47–60. doi:10.1006/toxs.1998.2436.

Gray Jr LE, Ostby J, Furr J, Price M, Veeramachaneni DN, Parks L. Perinatal exposure to the phthalates DEHP, BBP, and DINP, but not DEP, DMP, or DOTP, alters sexual differentiation of the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58(2):350–65.

Agas D, Sabbieti MG, Capacchietti M, Materazzi S, Menghi G, Materazzi G, et al. Benzyl butyl phthalate influences actin distribution and cell proliferation in rat Py1a osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101(3):543–51. doi:10.1002/jcb.21212.

Dobrzynska MM, Tyrkiel EJ, Pachocki KA. Developmental toxicity in mice following paternal exposure to Di-N-butyl-phthalate (DBP). Biomed Environ Sci. 2011;24(5):569–78. doi:10.3967/0895-3988.2011.05.017.

Crinnion WJ. Toxic effects of the easily avoidable phthalates and parabens. Alternative Med Rev: J Clin Ther. 2010;15(3):190–6.

Moral R, Wang R, Russo IH, Mailo DA, Lamartiniere CA, Russo J. The plasticizer butyl benzyl phthalate induces genomic changes in rat mammary gland after neonatal/prepubertal exposure. BMC Genom. 2007;8:453. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-453.

Moral R, Santucci-Pereira J, Wang R, Russo IH, Lamartiniere CA, Russo J. In utero exposure to butyl benzyl phthalate induces modifications in the morphology and the gene expression profile of the mammary gland: an experimental study in rats. Environ Health. 2011;10(1):5. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-10-5.

Dewitt JC, Copeland CB, Strynar MJ, Luebke RW. Perfluorooctanoic acid-induced immunomodulation in adult C57BL/6J or C57BL/6N female mice. Environ Heal Perspect. 2008;116(5):644–50. doi:10.1289/ehp.10896.

National Toxicology Program, NTP Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Butyl Benzyl Phthalate (CAS No. 85-68-7) in F344/N Rats (Feed Studies).

Lopez-Carrillo L, Hernandez-Ramirez RU, Calafat AM, Torres-Sanchez L, Galvan-Portillo M, Needham LL, et al. Exposure to phthalates and breast cancer risk in northern Mexico. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(4):539–44. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901091.

Kang SC, Lee BM. DNA methylation of estrogen receptor alpha gene by phthalates. J Toxi Environ Health A. 2005;68(23–24):1995–2003. doi:10.1080/15287390491008913.

Kim IY, Han SY, Moon A. Phthalates inhibit tamoxifen-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J Toxic Environ Health A. 2004;67(23–24):2025–35. doi:10.1080/15287390490514750.

Calafat AM, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Caudill SP, Tully JS, Needham LL. Serum concentrations of 11 polyfluoroalkyl compounds in the US population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2000. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:2237–42.

Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999–2000. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(11):1596–602.

Olsen GW, Burris JM, Ehresman DJ, Froehlich JW, Seacat AM, Butenhoff JL, et al. Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(9):1298–305.

Post GB, Cohn PD, Cooper KR. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), an emerging drinking water contaminant: a critical review of recent literature. Environ Res. 2012;116:93–117. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2012.03.007.

Henry ND, Fair PA. Comparison of in vitro cytotoxicity, estrogenicity and anti-estrogenicity of triclosan, perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid. J Appl Toxicol. 2011. doi:10.1002/jat.1736.

Lau C, Thibodeaux JR, Hanson RG, Narotsky MG, Rogers JM, Lindstrom AB, et al. Effects of perfluorooctanoic acid exposure during pregnancy in the mouse. Toxicol Sci. 2006;90(2):510–8. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfj105.

Yang C, Tan YS, Harkema JR, Haslam SZ. Differential effect of peripubertal exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid on mammary gland development in C57Bl/6 and Balb/c mouse strains. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;27(3–4):299–306. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.10.003.

Macon MB, Villanueva LR, Tatum-Gibbs K, Zehr RD, Strynar M, Stanko JP, et al. Prenatal perfluorooctanoic acid exposure in CD-1 mice: low dose developmental effects and internal dosimetry. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122(1):134–45.

Dixon D, Reed CE, Moore AB, Gibbs-Flournoy EA, Hines EP, Wallace EA, et al. Histopathologic changes in the uterus, cervix and vagina of immature CD-1 mice exposed to low doses of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in a uterotrophic assay. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33(4):506–12.

Biegel LB, Liu RC, Hurtt ME, Cook JC. Effects of ammonium perfluorooctanoate on Leydig cell function: in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;134(1):18–25. doi:10.1006/taap.1995.1164.

Sibinski L. Two-year oral (diet) toxicity/oncogenicity study of fluorochemical FC-143 in rats.: Riker Laboratories Inc/3m Company1987.

Lou I, Wambaugh JF, Lau C, Hanson RG, Lindstrom AB, Strynar MJ, et al. Modeling single and repeated dose pharmacokinetics of PFOA in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107(2):331–41. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn234.

Lopez-Espinosa M, Fletcher T, Armstrong B, Genser B, Dhatariya K, Mondal D, et al. Association of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) with age of puberty among children living near a chemical plant. Environ Sci Technol. 2011. doi:10.1021/es1038694.

Knox SS, Jackson T, Javins B, Frisbee SJ, Shankar A, Ducatman AM. Implications of early menopause in women exposed to perfluorocarbons. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(6):1747–53. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2401.

Innes KE, Byers TE. Preeclampsia and breast cancer risk. Epidemiology. 1999;10(6):722–32.

Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC, Long M, Bossi R, Ayotte P, Asmund G, Kruger T, et al. Perfluorinated compounds are related to breast cancer risk in Greenlandic Inuit: a case control study. Environ Health. 2011;10:88. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-10-88.

White SS, Stanko JP, Kato K, Calafat AM, Hines EP, Fenton SE. Gestational and chronic low-dose PFOA exposures and mammary gland growth and differentiation in three generations of CD-1 mice. Environ Heal Perspect. 2011;119(8):1070–6. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002741.

Frisbee SJ, Brooks ABJ, Maher A, Flensborg P, Arnold S, Fletcher T, et al. The C8 health project: design, methods, and participants. Environ Heal Perspect. 2009;117:1873–82.

Zhao Y, Tan YS, Strynar MJ, Perez G, Haslam SZ, Yang C. Perfluorooctanoic acid effects on ovaries mediate its inhibition of peripubertal mammary gland development in Balb/c and C57Bl/6 mice. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33(4):563–76. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.02.004.

Zhao Y, Tan YS, Haslam SZ, Yang C. Perfluorooctanoic acid effects on steroid hormone and growth factor levels mediate stimulation of peripubertal mammary gland development in C57Bl/6 mice. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115(1):214–24. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq030.

Zhao G, Wang J, Wang X, Chen S, Zhao Y, Gu F, et al. Mutegenicity of PFOA in mammalian cells: role of mitochondtia-dependent reactive oxygem species. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:1638–44. doi:10.1021/es1026129.

Lipworth L, Hsieh CC, Wide L, Ekbom A, Yu SZ, Yu GP, et al. Maternal pregnancy hormone levels in an area with a high incidence (Boston, USA) and in an area with a low incidence (Shanghai, China) of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(1):7–12. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6690003.

Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(6):229–39. doi:10.1186/bcr932.

Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Newbold RR. Disruption of the female reproductive system by the phytoestrogen genistein. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23(3):308–16. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.11.012.

Trock BJ, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R. Meta-analysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(7):459–71. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj102.

Wu AH, Wan P, Hankin J, Tseng CC, Yu MC, Pike MC. Adolescent and adult soy intake and risk of breast cancer in Asian-Americans. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(9):1491–6.

Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Pike MC. Epidemiology of soy exposures and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(1):9–14. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604145.

Su Y, Eason RR, Geng Y, Till SR, Badger TM, Simmen RC. In utero exposure to maternal diets containing soy protein isolate, but not genistein alone, protects young adult rat offspring from NMU-induced mammary tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(5):1046–51. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl240.

Hakkak R, Korourian S, Shelnutt SR, Lensing S, Ronis MJ, Badger TM. Diets containing whey proteins or soy protein isolate protect against 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced mammary tumors in female rats. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9(1):113–7.

Pei RJ, Sato M, Yuri T, Danbara N, Nikaido Y, Tsubura A. Effect of prenatal and prepubertal genistein exposure on N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mammary tumorigenesis in female Sprague–Dawley rats. In Vivo. 2003;17(4):349–57.

Whitsett Jr TG, Lamartiniere CA. Genistein and resveratrol: mammary cancer chemoprevention and mechanisms of action in the rat. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6(12):1699–706. doi:10.1586/14737140.6.12.1699.

Fritz WA, Coward L, Wang J, Lamartiniere CA. Dietary genistein: perinatal mammary cancer prevention, bioavailability and toxicity testing in the rat. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(12):2151–8.

Lamartiniere CA. Timing of exposure and mammary cancer risk. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2002;7(1):67–76.

National Toxicology Program, Multigenerational reproductive study of genistein (Cas No. 446-72-0) in Sprague–Dawley rats (feed study), 2008/08/08, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18685713.

Molzberger AF, Vollmer G, Hertrampf T, Moller FJ, Kulling S, Diel P. In utero and postnatal exposure to isoflavones results in a reduced responsivity of the mammary gland towards estradiol. Mol Nutr food Res. 2012;56(3):399–409. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201100371.

Latendresse JR, Bucci TJ, Olson G, Mellick P, Weis CC, Thorn B, et al. Genistein and ethinyl estradiol dietary exposure in multigenerational and chronic studies induce similar proliferative lesions in mammary gland of male Sprague–Dawley rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28(3):342–53. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.04.006.

Juan ME, Vinardell MP, Planas JM. The daily oral administration of high doses of trans-resveratrol to rats for 28 days is not harmful. J Nutr. 2002;132(2):257–60.

Levi F, Pasche C, Lucchini F, Ghidoni R, Ferraroni M, La Vecchia C. Resveratrol and breast cancer risk. Eur J Canc Prev. 2005;14(2):139–42.

Ortega I, Wong DH, Villanueva JA, Cress AB, Sokalska A, Stanley SD, et al. Effects of resveratrol on growth and function of rat ovarian granulosa cells. Fertil Steril. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.004.

Henry LA, Witt DM. Effects of neonatal resveratrol exposure on adult male and female reproductive physiology and behavior. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28(3):186–95. doi:10.1159/000091916.

Nikaido Y, Yoshizawa K, Danbara N, Tsujita-Kyutoku M, Yuri T, Uehara N, et al. Effects of maternal xenoestrogen exposure on development of the reproductive tract and mammary gland in female CD-1 mouse offspring. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18(6):803–11. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.05.002.

Provinciali M, Re F, Donnini A, Orlando F, Bartozzi B, Di Stasio G, et al. Effect of resveratrol on the development of spontaneous mammary tumors in HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Int J Cancer. 2005;115(1):36–45. doi:10.1002/ijc.20874.

Bhat KP, Lantvit D, Christov K, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Estrogenic and antiestrogenic properties of resveratrol in mammary tumor models. Cancer Res. 2001;61(20):7456–63.

Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CW, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997;275(5297):218–20.

Massart F, Saggese G. Oestrogenic mycotoxin exposures and precocious pubertal development. Int J Androl. 2010;33(2):369–76. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01009.x.

Kuiper-Goodman T, Scott PM, Watanabe H. Risk assessment of the mycotoxin zearalenone. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol: RTP. 1987;7(3):253–306.

Hilakivi-Clarke L, Onojafe I, Raygada M, Cho E, Skaar T, Russo I, et al. Prepubertal exposure to zearalenone or genistein reduces mammary tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(11):1682–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6690584.

Hilakivi-Clarke L, Cho E, Onojafe I, Raygada M, Clarke R. Maternal exposure to genistein during pregnancy increases carcinogen-induced mammary tumorigenesis in female rat offspring. Oncol Rep. 1999;6(5):1089–95.

Yuri T, Tsukamoto R, Miki K, Uehara N, Matsuoka Y, Tsubura A. Biphasic effects of zeranol on the growth of estrogen receptor-positive human breast carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(6):1307–12.

Saenz de Rodriguez CA, Bongiovanni AM, Conde de Borrego L. An epidemic of precocious development in Puerto Rican children. J Pediatr. 1985;107(3):393–6.

Fara GM, Del Corvo G, Bernuzzi S, Bigatello A, Di Pietro C, Scaglioni S, et al. Epidemic of breast enlargement in an Italian school. Lancet. 1979;2(8137):295–7.

Bandera EV, Chandran U, Buckley B, Lin Y, Isukapalli S, Marshall I, et al. Urinary mycoestrogens, body size and breast development in New Jersey girls. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409(24):5221–7. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.09.029.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclaimer

This review may be the work product of an employee or group of employees of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), however, the statements, opinions or conclusions contained therein do not necessarily represent the statements, opinions or conclusions of NIEHS, NIH or the United States government

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Macon, M.B., Fenton, S.E. Endocrine Disruptors and the Breast: Early Life Effects and Later Life Disease. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 18, 43–61 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-013-9275-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-013-9275-7