Abstract

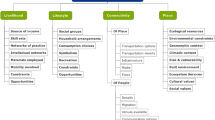

This paper focuses on urban discourses as powerful instruments intertwined with the dialectic of inclusion and exclusion. First, three dominant contemporary urban discourses developed in the field of urban planning are scrutinized on their inclusiveness of families and daily family life. The attractive city, the creative city and the city as an emancipation machine are examples of urban discourses communicated top-down via reports, debates and media attention. It is argued that these three discourses do not address families as urban citizens nor the very notion of reproduction and its daily manifestation. The exclusionary character of contemporary urban discourses does not only result in a neglect of urban families, it also legitimates non-intervention when it comes to family issues. This conclusion activated the search for an alternative discourse as expanded in the second part of the paper. This alternative discourse is constructed from the bottom-up and is rooted in the day-to-day experiences of urban families themselves. It is a refined discourse, with interrelated geographical scales including the city as a whole, the neighbourhood, the street and the home. This is a city that integrates—as families themselves do—the different domains of life. The city is appreciated for its qualities of proximity, the neighbourhood for its ethnically mixed children’s domains, the street as an urban haven and the house as the place that accommodates private life for each member of the family. This alternative discourse is called the balanced city. The empirical basis is drawn from middle-class urban families in Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Cities have always given food for thought. The simple question of what makes a city or what constitutes urbanism provokes much discussion and deliberation. Simple answers are seldom given. Instead, complex arguments are put forward that relate to different discourses of the city. Discourses can be considered as interpretative frameworks that not only help us to understand reality but also to develop ideas about future, more ideal situations. Discourses are social constructions that are in a permanent struggle to become the dominant interpretation frame (Giddens 1979). They are part of a hegemonic project that serves certain aims and specific groups. Which city is being referred to (and which not), which groups are represented (and which not), and what future direction is opted for? Urban discourses seek to become part of the dominant regime of thinking and focus on specific sides of the city, while putting other parts of reality aside. At the same time, they form the leading ideal for the reconstruction of cities. That makes urban discourses contested. They are used as a legitimate basis for urban interventions and for the neglect of ‘minor’ issues or ‘minor’ actors (Terlinden 2003). Discourses form a legitimization of urban interventions and as such they are powerful instruments intertwined with the dialectic of inclusion and exclusion (Hajer 1989).

A central theme of this paper is the existence of different urban discourses related to the position of professionals on the one hand and the position of urban residents on the other hand. First, there are the well-known urban discourses constructed in the field of urban planning and communicated from the top-down. Examples of contemporary urban planning discourses discussed in this paper are the attractive city, the creative city and the city as emancipation machinery. These discourses are globally constructed, be it with local specificities. Second, there are the discourses of the city referred to by residents and communicated from the bottom-up. Residents construct their urban discourse on a day-to-day local basis. Residential discourses are discussed among residents themselves and sometimes exchanged with urban planners, but they are fragmented, not well articulated and hard to grasp. That makes residential discourses a difficult category to incorporate in urban planning.

The first aim of this paper is to scrutinize existing urban planning discourses for their inclusiveness of family life in cities. To what extent do current urban discourses include day-to-day family life in cities (Fincher 2004)? The answer to this question turns out to be rather negative, as will be made clear. When current urban discourses systematically marginalize families and family issues, there is a need for a new inclusive urban discourse rooted in the daily experience of residential families. If we want to change practice, we have to change the tool with which we look at and interpret urban processes and city life. Therefore the second aim of this paper is to develop an alternative discourse, one that takes daily family life in cities into account.

The choice for the residential category of urban families is twofold. First they represent a considerable number of citizens. Whereas suburbanization of families continues to be a dominant trend, there are signs that cities are growing in importance as places for families to live. A great number of migrant families choose or are forced to live in the big western cities (Musterd and Ostendorf 1998). In addition, a new urban orientation of middle-class families seems to be on the rise (Butler 2003; De Meester et al. 2007). Second, it is evidently clear that daily life in cities is not easy for families (Christensen and O’Brien 2003; Skinner 2003; Jarvis 2005; Chawla 2002). It is precisely in cities that the negative consequences of the accelerating pace of life, demanding jobs, and housing problems are felt. Health conditions are steadily becoming worse, particularly for disadvantaged children growing up in the least attractive areas of the urban landscape (Power 2007). To improve living conditions for families, these conditions have to become part of a powerful urban planning discourse.

The structure of this paper is as follows. First, I describe and analyse three contemporary urban discourses in the realm of urban planning. Second, I turn to day-to-day reality of ‘neglected’ urban families in the Netherlands. In this paper, this reality is exemplified by Rotterdam middle-class working households with children growing up, including migrant families (Karsten et al. 2006). The paper ends with some conclusions and a discussion.

2 Three urban planning discourses

Different urban discourses are tumbling across each other in the realm of urban planning. Starting from recent policy reports and media attention in the Netherlands today, analytically we can distinguish three important urban discourses: the attractive city, the creative city and the emancipatory city. These discourses may be overlapping to some extent, but each discourse conceptualizes the city from a specific point of view: consumption, production and housing.

The attractive city focuses on the city as a leisure domain, highly attractive for a broad range of consuming activities: the ‘out’-city (Burgers 2002; Van der Land 2005). The city thrives on a form of urbanism related to visitors’ urbanism, including tourism, culture, shopping and entertainment (Judd and Feinstein 1999; Zukin 1995). The city is to be consumed by a wide variety of people spread all over the region. Residents may be an important category of consumers, but they are certainly not the most important ones. Some authors believe that too much emphasis on the out-city will create cities without much commitment (Zijderveld 1998). People who visit the city for leisure aims do not care very much about its social and economic qualities. They visit only specific parts, particularly the centre of the city. The problem is not that places of consumption are high on the agenda; also urban residents may profit from them. It is the kind of consumption places that makes this discourse problematic for residents. The discourse of the attractive city legitimates major investments in culture and shopping places. The aim is not in the first place to accommodate residents, but to attract as many tourists and other visitors as possible and in so doing to reach the highest positions on the ranking list of (competing) cities.

The discourse of the creative city has pervaded the western world in only a couple of years (Landry 2000; Florida 2002; Deben and Bontje 2006). Is there any city which does not strive to become ‘creative’? In this discourse, it is clear that consumption in cities is not considered to be enough to justify success. The creative city is primarily concerned about production, or more precisely, creative production. To become creative, a city must attract the creative class: well-educated workers who value creativity, individuality and diversity. The idea is that where this new middle-class settles down, firms follow and try to fit into the urban fabric. That would make cities economically healthy. The creative class is imagined as a hard-working population but—it would seem—with enough time left over from work to spend several hours a week on urban leisure and networking. Creative cities are productive places with a varied consuming infrastructure. The members of the creative class are frequent visitors of congenial cafés and international restaurants—public spaces that facilitate successful networking. Getting home on time is not a matter of great concern. Although they may be part of the creative class, hard-working parents with family responsibilities at home do not feature in the discourse of creative cities. Thus, their family needs are easily overlooked. The whole discourse of the creative city is very much an economic story, more so, in fact, than Florida (2002) has indicated. The main ambition—after the wish to become a creative city—is to become a prosperous city (ranking high on another list).

The city as emancipation machinery has recently been widely discussed in the Netherlands (Reijndorp and van der Zwaard 2004; Platvoet and Van Poelgeest 2005). The emancipation machinery concept stresses the emancipating, liberating and enriching dimension of cities for citizens (Lees 2004). Cities are places where one can rise on the societal ladder. Furthermore the discourse of the emancipatory city emphasises the positive climate in cities where there is a place for people working themselves up to higher status groups. That is the reason that the emancipatory machinery stresses the quality of cities as locations of education and employment, the classic stimuli to enable individual capital to grow. The residential function of cities is seen as very important. Housing policy is aimed at accommodating young newcomers without families and with low economic potentials. That creates an emphasis on small, compact and (if possible) cheap housing. Residents are said to leave the city again once they have established their individual careers and collected enough capital. The city is a place in which progress in life can be made, but progress in the life course, starting a family, is not given much attention. That makes claiming a more spacious dwelling difficult. The emancipatory city is only a temporary space to stay—up and out, like the Americans say.

All three discourses stress different aspects of city life, but none of them show very much awareness of family life in cities. The first—the attractive city—is very clear on this point. Cities are first and foremost places to visit and a place for tourists. Intervention is therefore mainly directed to the city centre or another location with alluring attractions. Consumption places used on a daily basis in residential neighbourhoods are not the focus of this discourse. The creative city is about residents producing and consuming city life. This may include families with children. But looking at the facilities considered necessary to become a creative city, it is more about glamorous meeting places, stylish shops, galleries and so forth. Cities have to become nice-looking places where one can work in a leisurely context. Urbanites seem to be mainly young and without family responsibilities. Diversity is considered to be important, although not with respect to age. Children do not participate in the creative city. This omission is curious, because a considerable part of the creative class has (or will have) children at some time. The concept of the creative class seems to be based on the residential category of yuppies: small, urban, childless households who want to live their lives at the top in or near the city centre. The emancipation machinery may have worked for some families, but as soon as they are able to make the next step in their housing career, they feel that they are no longer welcome. Because family housing is considered to take up too much space, it is only very marginally available. Families that have collected enough capital are supposed to leave to make room for new starters. Thus, family housing does not have much priority in the emancipatory city, nor do family-friendly neighbourhoods.

What is missing in all three discourses is the notion of reproduction and its day-to-day manifestation. It is the daily life of urban families that seems to be hidden (Jarvis et al. 2001; Costello 2005). Families living in the city may go shopping in the city centre, but they also need to do their daily errands in order to keep their household running. Working families may be productive as members of the creative class, but they are also engaged in caring and household tasks. It is this part of urban life—often seen as ‘only’ private—that is neglected in current urban discourses and consequently by urban planning. Not only do working parents have a lot more to do than be productive; they are also faced with the challenge of integrating their public (job) and private (care) activities on a daily basis. That dual task makes daily life rather complicated in terms of space and time. Parents’ work forces families to organize their lives spatially and temporally in order to balance career and care. The location of their dwelling is a crucial long-term decision in this respect. For working families dependent on the urban labour market—notably many creative workers—an urban living location is a serious option if not a necessity (Brun and Fagnani 1994; Karsten 2007). It can be concluded that city-dwelling families are only marginally mentioned in the three urban discourses analysed here and that the current discourses do not include family life or reproduction in general.

3 Design of the empirical research

In order to gain insight into the social construction of the city by families themselves, we held lengthy interviews with 30 middle-class family households living within the ring of Rotterdam, an ethnically mixed city of nearly 600,000 inhabitants in the Netherlands (Karsten et al. 2006). The respondents lived either in an older neighbourhood, North Rotterdam, or in a newly built neighbourhood called Stadstuinen. Both neighbourhoods are centrally located within walking/cycling distance of the city centre. All households are working households and all have a middle to higher level of education. All the couples interviewed had already been living in Rotterdam for a long time and some had actually been brought up there themselves. The majority started to live in Rotterdam at the beginning of their educational career, roughly around the age of eighteen. Step by step they became acquainted with city life and they decided not to change their urban habitat when they had children. Life with children started relatively late for these families. Many of them had already passed the age of thirty when they had their first child. In that respect they mirror the ongoing process in the Netherlands of well-educated women postponing motherhood. All those interviewed had made some form of housing career, several within their own neighbourhood. Nearly all work in the city where they live; they appreciate that proximity highly. Most do not need cars on a daily basis, and seven households in North Rotterdam decided that they did not need a car of their own. The symmetrical family, which in the Dutch context is the dual-earner family with both partners working for 4 days a week, is well represented compared with the figures for the Netherlands as a whole. The same applies to the kinds of job: an emphasis on the social-cultural and public sector. It would be a mistake to think of these urban families as wealthy. They all are middle-class, mainly by virtue of their education, though only some of them have a successful career and earn a good salary; others put more emphasis on pleasant work and personal engagement.

All respondents share an urban orientation, although from time to time they all feel unsure about their living location. Some are hesitant about their choice to live in the city because of the children; some had doubts because of declining safety and other negative experiences. Only a very few, however, expressed a desire to exchange their urban location for the suburbs. Respondents were selected among residential families living in the two selected neighbourhoods using the snowballing method. We were very careful to incorporate families that are as diverse as possible within the selection criteria (middle to higher educated working families with children). Children varied in age from 1 to 16 years old. Among the group of interviewees were five single-parent households. One-third of the families had a migrant background.

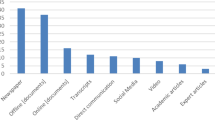

The interviews covered, among other topics, housing preferences, the pleasures and downsides of urban life, the struggles of daily life and the combination of having children and living in a central urban environment. The interviews were fully transcribed and included a short survey. The family households interviewed use the city on a daily basis in various ways, and all have daily positive and negative experiences. In the interviews they report on their involvement with the city and relate positive and negative issues to their personal ideal of the city. Transcripts of the interviews were considered to be narratives about the city from a family position. Fragments of the interviews have been used as elements for the construction of a new alternative urban discourse rooted in the daily experiences of a specific group of urban families: the relatively new residential category of urban middle-class families. The middle-class perspective limits the generalisation of the findings. This paper is only a first step in broadening the scope of urban planning discourses in the direction of family life. Further research is needed to incorporate more and more diverse family perspectives.

4 The social construction of the city from a family position

Interviewing the Rotterdam families made it clear that the city was not an abstract context to them. The families put forward lengthy arguments about their involvement with the city they live in. The city they refer to is an ideal, rooted in daily practice. None of the interviewees referred to one of the three urban discourses explicated above. Interviewees stressed the accommodating dimension of cities and its shortcomings. Their stories can be analysed in different layers related to different but interconnected geographical scales: the city as a whole, the neighbourhood, the street and the house. They have a sophisticated view of the city as the result of the daily paths taken through their urban environment. It became clear that urban conditions were not considered to be static; families were actively working on making the city more suitable for family life. In this sense, these families are not only consuming the city or just complaining about restrictions; they are also actively engaged in moving the city in a more favourable direction for family life.

4.1 City: proximity, culture and diversity

The city the families were talking about is a diverse city with everything at hand: a place of home, work and high amenity. The families value the centre of the city and the centrality of their housing location: very central, only one bridge from the centre, within a 5-minute bicycle ride, were a few of the positive comments. They want to live in a location with the world within walking distance. In fact they usually take the bicycle, but the argument is clear. They cherish the practical advantages of living close to many different amenities, including work. It is no coincidence that almost all the interviewees work in the city where they live. The need for accessible work—in combination with reproductive tasks—puts mobility high on the agenda. Rotterdam is sometimes called the most accessible city of the Netherlands; however, this attribute applies mainly to the perspective of commuters and others who want to reach the city from outside. Our respondents value internal mobility, with easy travel from one part of the city to another and combining different places in one journey. A city that facilitates fast and safe criss-cross rides by public transport and bicycle within the city is more highly appreciated than one that offers ease of access from outside.

People differ according to what precisely they appreciate in ‘living nearby’. Some are fond of the museum quarter and the many festivals. Some value the cheap and exotic markets, special shops or eating-out places. Some praise the proximity of the famous central library, the cinema, or specific children’s domains. All families considered a cultural and diverse ambiance to be an important urban delight that was capable of counterbalancing the sometimes heavy burden of urban family life. When they have the idea that the cultural infrastructure of the city is about to deteriorate, they worry. This concern applies to both high and low culture and includes the cultural infrastructure for children. A mother working as a musician herself:

What we are very much concerned about is the cutting of subsidies for arts and culture. If you want us to leave Rotterdam, you will have to start by banishing the nice things of city life. They think music lessons and so on are something for the elite. But everything that culture entails is important for a city that’s alive. The same applies to cultural activities for children, they’re really important and not just for the happy few.

A city with a great variety of facilities and people is appreciated. Children growing up in such a city are considered to benefit from a diverse multicultural urban scene:

We made a conscious choice to live with our children in this big city. Of course, it is we who appreciate urban life; we are city people, real urbanites. And when parents feel good, that is good for the children. But we think that it is also a good choice for our children. There are plenty of things for them to do. We only have to step out of our front door and there is a whole square waiting for us. There are museums, friends, and playgrounds, all within walking distance. And there are many different kinds of people living in this neighbourhood. That multicultural atmosphere is the future they have to learn to cope with. For us, that is a big advantage of living in the city. And that is why we sent them to this black school nearby.

It is the presence of children which forms one of the filters through which these families look to weigh the pros and cons of city life, as will be elaborated on below.

4.2 Neighbourhood: ethnically mixed children’s domains

Our Rotterdam families do not turn their backs on the problematic side of the city. They have already lived in it for many years and know what the challenging sides of urban life are. Most of the parents work in the public sector of education, research, arts, journalism, and so forth. They are engaged in the multicultural society on a daily basis. All the interviewees stressed their preference for daily shops and services including childcare, schools and a range of other children’s domains to be located in the vicinity.

On the geographical scale of the neighbourhood, the choice of a school is crucial (Butler and Robson 2003). Parents are looking for an ethnically mixed school in the vicinity, but they all want a school where their child can also have extra classes from music to sports or creativity. It is clear that these middle-class parents want to educate their children with the cultural baggage they find important. Education ‘only’ in the restricted sense of grammar and mathematics is not enough, but that is what many schools with a high share of migrant pupils are concentrating on. ‘Black’ neighbourhood schools are—except by a very few—not considered to be suitable precisely because of that ‘narrow’ curriculum:

A primary school nearby is what we would think of as being very convenient. My son attends a school in Hilligersberg (a neighbouring neighbourhood) and that means that his friends live somewhere else. Of course, you can make appointments for the time after school, but that is not very convenient. We would have liked a mixed school for our son, but there is not much available. The nearest school is completely black. We wanted to let him have music lessons, but that is not on the programme there. They are preoccupied with the standard curriculum. That is a pity; we were in favour of extra music classes….

We hear regret and resignation. Other parents follow the same argument but come to a different choice: they let their preference for a school nearby prevail over the wish for cultural classes:

Well, school choice is a nasty business, that is something we looked out for. But that didn’t turn out to be a big problem. We visited all the primary schools in the neighbourhood and in the end we chose the Margrietschool. That is a mixed school, exactly what we wanted. We also had another school in mind, a little bit further away and near the centre, that is a school with a cultural programme and culture is important for us, but we think that a school in our own neighbourhood is important, too. That taking and picking up your children over a large distance is a disadvantage. And, well, a completely black school was not our idea, as is the case with the Blijburg school, too elite and completely white.

Both neighbourhoods studied have a variety of public primary schools. The majority of them have a high share (over 70%) of migrant pupils reflecting the population composition of the Rotterdam neighbourhoods. Only a very few are ‘white’ (less than 30% of migrant pupils) schools and the same applies for ethnically mixed schools. The majority of the families interviewed opted for the mixed school; some chose a ‘white’ and culturally high-standard school (sometimes outside the neighbourhood) and only three chose a neighbourhood school with a majority of migrant students. Parents’ arguments sound very politically correct; they are looking for extra-curricular activities, not selecting a specific school population. Nevertheless, we did not get the impression that these families wanted to avoid their ethnically mixed neighbourhood population. Families who want to distance themselves radically from ethnic diversity have already chosen to leave the areas studied. These urban families—about a third of whom have ethnic-minority origins themselves—are searching for a certain balance. They are trying to develop everyday strategies to manage contact with socially different groups. It is the ‘right’ distance they are looking for, and the lower the geographical scale, the more important that right distance is.

4.3 Street: urban haven

The preference for an urban central residential location in a culturally diverse context is clear, but it is only half the story. Although many people consciously prefer the city to the suburbs as the place to bring up their children, it is also the presence of children that creates a longing for what reflects the idea of an urban haven. These families accept that that is not always possible, but they try to establish small niches—preferably their own street or block—where physical and social conditions are favourable for bringing up children (Karsten 2008).

Favourable physical conditions are low-traffic green streets and playable space. A preference for green does not necessarily mean a big park, but it does include some simple street greenery, with small front ‘gardens’. It is more about a friendly green appeal. In this respect, the newly built Stadstuinen is not valued positively and the urban planning is blamed for that:

I think there is a shortage of green here. It is all too stony, no trees. In this street there are only very small trees on just one side of the street. It is all buildings around here. There seems to be a disease among designers who only make plans like here: straight, stone, and dark. Where is the neighbourhood they promised in the folder: a garden city? It is only city, no garden.

Residents can only manage their physical conditions themselves to a certain degree. The people living in Stadstuinen, the neighbourhood mentioned above, succeeded in improving the amount of green in their ‘garden park’ slightly: two big trees have been (re) planted. In North Rotterdam it is quite customary to put some big pots with plants next to the front door. It is clear that these families consider the public space around their home as an extension of their private space. Together with their neighbours they are gradually constructing new communal spaces. Reducing traffic (speed) is an important aim, communally striven for:

We are active Rotterdam residents, active in particular for our own neighbourhood. We organized a little festival and we are members of the street-traffic group. That is mainly about too many cars and driving too fast. The traffic makes a lot of noise as well. Sometimes the houses here actually shake. We succeeded in getting a reduction in the speed allowed. Now our street is a 30 kph street. Thank goodness!

Playable space is an important physical dimension of an urban haven. In the Netherlands, parents consider playing outdoors to be good for children and city parents are no exception in this respect. But the wish for playable space close at hand has also to do with the daily life of the parents themselves. Parents are busy and they find it very convenient if they can do what they want at home while the children play in front of the house or in the back garden. Playable space does not necessarily mean a formally constructed playground: broad pavements, communal back gardens, and even roof terraces are popular play spaces. Such spaces accommodate the combination of playing, caring, working, socializing and networking with the neighbours. The families in Stadstuinen have a communal back garden and they are very pleased about that:

The path behind our house is really fantastic. In collaboration with the neighbours, we created a closed back path and that means that children can explore this inner block completely. There are lots of other children to play with. That is really fantastic and we don’t have to look after them all the time. The children can walk into the gardens of all our neighbours. During the summer they go from one wading pool to the next!

The families interviewed turned out to be very creative about creating playable space: fences between backyards have been demolished to create bigger shared play spaces; pavements are claimed by placing benches; and wasteland is turned into a temporary green (play) oasis. Working together with the neighbours is a prerequisite for success. Many hands make light work and it becomes possible to exchange responsibilities, like looking after the children or maintaining the greenery. But communal initiatives are only successful when people have more or less the same ideas about bringing up children and neighbourly practices. This creates a demand for enough ‘people like us’ in the street: the social dimension of an urban haven.

On the geographical scale of the street, the need for some neighbours ‘like us’ is apparent. Like-minded people are households of about the same social class and with children of about the same age. That does not mean that all residents in the street should have the same background. A homogeneous street does not fit well in the urban ideal of these families who favour centrality and diversity. They dislike the suburbs precisely because of the endless rows of identical houses with identical families. With their wish for people ‘like us’ they are looking for the ‘right’ balance. The presence of some children living nearby is considered to be a prerequisite:

That’s what we think of as very important: other residents with children living in this street. Trees (8) is our only child, so it is very nice that we know many other families living here. And it’s because of the children, at least that is our experience, that we get to know other families. It generates a sort of social control, not very much, but enough. Here in this street, they all know our daughter and when a child starts crying we all know where it belongs. Then we bring the crying child home and that’s what all the neighbours do here.

It is well documented that homogeneous neighbours have more social contacts than neighbours who differ in status and household situation (Gans 1968; Butler 2003; Mazanti 2005) and the families in Rotterdam who were interviewed are no exception to this rule. They emphasize the importance of having like-minded families nearby. And as has been made clear, the social dimension of an urban haven also has a practical dimension. It facilitates the exchange of all kinds of practical services including childcare.

4.4 Appropriate housing

Cities are places with a high number of small houses and apartments. Over half the houses in Rotterdam have only three rooms or less: too small for families (www.cos.rotterdam.nl). The search for a house that is spacious enough but still affordable is something that concerns all families. It is difficult to get a home that is big enough to accommodate all the different family members in a ‘middle-class way’: all members of the family with rooms of their own. On the lowest geographical scale the dominance of current discourses on the city is very manifest: the supply of spacious housing is not a matter of priority. Interestingly enough, the argument used to defend the low investment in larger houses is that there is no place for spacious housing in the city. However, the great majority of urban apartments only accommodate one or two people. It takes at least the space of two apartments to house the same number of people that the mean family has.

The hunt for affordable housing in a situation of scarcity is a cause for widespread concern. Not all families have ample financial resources. And some families—notably the North Rotterdam residents—do not want to buy an expensive house, because they do not want to commit themselves irrevocably into the future. They want to feel free:

Sometimes people ask me: why don’t you buy a house? Particularly my family…But we don’t want to structure our lives too much, with that entire financial burden…We don’t want a heavy mortgage and a feeling that we can’t afford things we want.

Appropriate housing does not only mean appropriate space: it is also a matter of taste. Original details, high ceilings, spacious living areas are preferred. Most families want a garden, but they seldom refer to a typical suburban detached house with a big garden. Instead, they favour communal green in combination with a small garden of their own or a private place where they can sit outdoors. Some prefer a house with garden simply to live downstairs: A garden is very important for us. Or actually for my partner. It doesn’t make much difference to me, but I hate carrying buggies and shopping upstairs.

Families who prefer an apartment to a single-family house have been thinking about the installation of a small lift for goods and shopping. All families share a wish for private access to the street: a front door at street level. That means that high-rise buildings are not popular, but apartments built in storeys above each other would meet some of these families’ preferences.

5 To conclude: the bottom-up ‘balanced’ city

This paper makes it clear that urban discourses are widely contested, not only within the field of urban planning but also when comparing professionally based and residentially based discourses. It is argued that dominant urban discourses in the field of urban planning, such as the attractive city, the creative city and the city as emancipatory machinery, tend to overlook the day-to-day life of residents and particularly of family residents (Fincher 2004; Costello 2005). That makes professional discourses focus on city centres and less so on residential environments. Based on empirical research in Rotterdam, the aim was to construct a residentially based alternative discourse. This bottom-up discourse is called the balanced city. The specific group interviewed, only middle-class families, and the limited number of interviewees put restrictions on the breadth and reach of this discourse.

The different layers of the city the urban families refer to suggest a refined multi-dimensional urban discourse with interrelated geographical scales. In contrast to the urban discourses that have been professionally developed in the field of urban planning, not only are the lower geographical scales of the neighbourhood, the street and the home included, but they are also accorded equal importance. The urban-family city is constructed around cultural outings, daily practice, communal actions and residential preferences. In addition, it is the presence of children which forms the filter through which the interviewed families weigh the pros and cons of city life. Being urbanites—i.e., defining themselves as city people—is reflected in their preference for an urban location near the city centre with its broad range of amenities, including work and culture, near at hand. Mobility is valued in terms of internal mobility, within the city borders. Culture is not only considered as an adult issue: cultural domains for children are equally important. The neighbourhood is much favoured as a place where children can get used to the ethnically mixed city of the future. Mixed schools are the local domains where contacts with different social and ethnic groups can best be practiced. On the geographical scale of the street, the importance of like-minded families is stressed. Urban streets have to accommodate physical and social conditions for family life. That means traffic-calm green streets with playable spaces, networking families and neighbour children. Urban homes have to be big enough to house families in an appropriate way, with enough space for all the members of the family and at not too high a price.

The balanced city is one that is valued not only for new forms of productivity (creative cities) or for the consumption of exciting leisure amenities (the ‘out’ city), but also for an infrastructure which facilitates reproduction tasks, children’s culture and family housing. This is a city that integrates, as families themselves do, the different domains of life at different geographical scales. And socially it includes different categories of households. The balanced city would be a city with enough space for households with children, but not only for families. The city these families are striving for is a city reconciling families and cities, children and urban, private and public, production and reproduction. The discourse of the balanced city is constructed from the bottom-up and as such it provides an alternative for urban discourses in the world of urban planning. Urban planners could use it as a tool to help provide families with better accommodated cities. This will not only benefit the middle-class families discussed here but also working-class and migrant families who on the whole will have even more difficulty with the struggles of daily life in contemporary big cities (Power 2007; Karsten 2005).

References

Brun, J., & Fagnani, J. (1994). Lifestyles and locational choices. Urban Studies, 31, 921–934.

Burgers, J. (2002). De gefragmenteerde stad. Amsterdam: Boom.

Butler, T. (2003). London calling. The middle classes and the remaking of inner-London. Oxford: Berg Press.

Butler, T., & Robson, G. (2003). Plotting the middle classes: Gentrification and circuits of education in London. Housing Studies, 18, 5–28.

Chawla, L. (Ed.). (2002). Growing up in an urbanising world. London: Earthscan.

Christensen, P., & O’Brien, M. (Eds.). (2003). Children in the city. Home, neighbourhood and community. London, New York: Routledge Falkner.

Costello, C. (2005). From prisons to penthouses: The changing images of high-rise living in Melbourne. Housing Studies, 20(1), 49–62.

de Meester, E., Mulder, C., & Droogleever Fortuijn, J. (2007). Time spent in paid work by women and men in urban and less urban contexts in the Netherlands. TESG, 98(no. 5), 585–602.

Deben, L., & Bontje, M. (Eds.). (2006). Creativity and diversity. Key challenges to the 21st-century city. Amsterdam: Spinhuis.

Fincher, R. (2004). Gender and life-course in the narratives of Melbourne’s high-rise housing developers. Australian Geographical Studies, 42(3), 325–338.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class. New York: Basic Books.

Gans, H. (1968). People & plans. New York: Basic Books.

Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory. Houndmills: Macmillan Education.

Hajer, M. (1989). City politics. Aldershot: Avebury.

Jarvis, H. (2005). Work/life city limits. Comparative household perspectives. Hampshire, New York: Palgrave.

Jarvis, H., Pratt, A., & Wu, P. (2001). The secret life of cities: The social reproduction of everyday life. Harlow: Pierson Education Ltd.

Judd, D., & Feinstein, S. (Eds.). (1999). The tourist city. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Karsten, L. (2005). It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban children’s daily use of space. Children’s Geographies, 3, 275–290.

Karsten, L. (2007). Housing as a way of life. Towards an understanding of families’ preferences for an urban residential location. Housing Studies, 22, 83–98.

Karsten, L. (2008). The upgrading of the sidewalk: From traditional working-class colonisation to the squatting practices of urban middle-class families. Urban Design International, 13, 61–66.

Karsten, L., Reijndorp, A., & van der Zwaard, J. (2006). Stadsmensen. Leefwijzen en woonambities van stedelijke middengroepen. Amsterdam: Aksant.

Landry, Ch. (2000). The creative city. A toolkit for urban innovators. Near Stroud: Earthscan Publications.

Lees, L. (2004). The emancipatory city. London: Sage.

Mazanti, B. (2005). A sense of community in a modern world. Paper presented at the ENHR conference Reykjavik, 29 June–3 July.

Musterd, S., & Ostendorf, W. (1998). Urban segregation and the welfare state: Inequality and social exclusion in western cities. London: Routledge.

Platvoet, L., & van Poelgeest, M. (2005). Amsterdam als emanciaptiemachine. Bussum: Uitgeverij THOTH.

Power, A. (2007). City survivors: Bringing up children in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. University of Bristol: Polity Press.

Reijndorp, A., & van der Zwaard, J. (2004). Op zoek naar de middenklasse. In F. Becker (Ed.), Rotterdam. Het vijfentwintigste jaarboek voor het democratisch socialisme. Amsterdam: Mets & Schilt en Wiardi Beckman Stichting.

Skinner, C. (2003). Running around in circles: Coordinating childcare, education and work. York: Policy Press.

Terlinden, U. (Ed.). (2003). City and gender. International discourse on gender, urbanism and architecture. Opladen: Leske+Budrich.

van der Land, M. (2005). Vluchtige verbondenheid. Stedelijke bindingen van de nieuwe Rotterdamse middenklasse. Rotterdam: Erasmus Universiteit.

Zijderveld, A. (1998). A theory of urbanity. The economic and civic culture of cities. New Brunswick, London: Transaction Publishers.

Zukin, S. (1995). The cultures of cities. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Karsten, L. From a top-down to a bottom-up urban discourse: (re) constructing the city in a family-inclusive way. J Hous and the Built Environ 24, 317–329 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-009-9145-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-009-9145-1