Abstract

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of and factors associated with tobacco use among patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection. Patient reported outcomes (PROs) were analyzed of patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection (n = 313) who presented for clinical evaluation and treatment of HCV between 2013 and 2017 at a university-affiliated HIV/HCV Co-infection Clinic. The prevalence of tobacco use in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection was 48%. Compared to non-smokers, a higher proportion of tobacco smokers had substance use disorders and concurrent alcohol and substance use. In the multivariate analysis, concurrent alcohol and substance use was positively associated with tobacco use. The findings suggest clinical interventions are urgently needed to reduce tobacco use among patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection—a doubly-vulnerable immunocompromised population. Otherwise, failed efforts to dedicate resources and targeted behavioral interventions for this respective population will inhibit survival—especially considering the recent and evolving COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although tobacco use has declined over the past 50 years (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US), 2014), it continues to be the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States (U.S.), accounting for over 480,000 annual deaths. The existing evidence indicates that tobacco use has adverse health effects on almost all parts of the human body (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US), 2010, 2014), yet 14% (34.2 million) of adults ≥ 18 years old (16% males; 12% females) were current cigarette smokers in 2018 (Creamer et al., 2019). Thus, while it has been established that tobacco use causes chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US), 2010, 2014), increasing evidence indicates that it worsens disease progression of several infectious diseases—in particular human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Bean, Richey, Williams, Wahlquist, & Kilby, 2016; Helleberg et al., 2013; Nahvi & Cooperman, 2009; Tesoriero, Gieryic, Carrascal, & Lavigne, 2010).

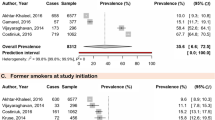

Tobacco use in patients living with HIV exacerbates the natural history of HIV by negatively affecting both innate and adaptive immune responses (e.g. T helper cells, CD4 regulatory T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells) (Arnson, Shoenfeld, & Amital, 2010; Calvo, Laguno, Martínez, & Martínez, 2015; Feldman & Anderson, 2013; Steel et al., 2018; Strzelak, Ratajczak, Adamiec, & Feleszko, 2018). Not only does tobacco use alter and hinder immune and virological responses in patients living with HIV, it increases susceptibility to acquisition and development of opportunistic infections and medical conditions—including among patients living with HIV who are actively receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Petrosillo & Cicalini, 2013; Rahmanian et al., 2011). In particular, tobacco use in patients living with HIV increases the risk for lower respiratory tract infections, bacterial pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease COPD, cardiovascular disease, and various types of malignancies (Petrosillo & Cicalini, 2013; Rahmanian et al., 2011). Consequently, tobacco use has emerged as a leading cause of death in patients living with HIV (Shuter, Kim, An, & Abroms, 2018). It is estimated that patients living with HIV who are actively receiving ART will lose more years of life due to smoking than due to HIV (5.1 years lost to HIV; whereas, 12.3 years lost to smoking) (Cropsey et al., 2016; Helleberg et al., 2013). Despite the synergistic effects of tobacco use and HIV infection, prevalence estimates of tobacco use in the U.S. in patients living with HIV are three times higher than the general population (50–70% vs. 15–20%) (Bhatta, Subedi, & Sharma, 2018; Rahmanian et al., 2011).

Similarly, the most recent epidemiologic study estimated that the prevalence of tobacco use in those living with HCV (62%) is three times higher than the general population (Kim et al., 2018). Although literature that characterizes the negative effects of tobacco use in patients living with HCV is not as well established as HIV literature, tobacco use also worsens the natural history of HCV (Zhao, Li, & Taylor, 2013). Tobacco use in patients living with HCV is associated with a heightened risk for pulmonary disease, elevated liver enzymes (i.e. ALT), and acceleration of disease progression to advanced stages of liver fibrosis and liver cancer (Gartner, Miller, & Bonevski, 2017; Hézode et al., 2003; Pessione et al., 2001; Shuter et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2013).

More than a third of patients living HIV in the U.S. are living with HCV co-infection (HIV/HCV) (Easterbrook, Sands, & Harmanci, 2012; Koziel & Peters, 2007; Taylor, Swan, & Mayer, 2012). Due to the synergistic effects of HIV and HCV, patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection have greater risks of both HCV and HIV-associated morbidity and mortality compared to patients with HIV or HCV mono-infection (Bosh et al., 2018; Konopnicki et al., 2005; Re et al., 2014; Teira & VACH Study Group, 2013; Thein, Yi, Dore, & Krahn, 2008). Tobacco use further amplifies pathophysiological synergistic effects of HIV/HCV co-infection, and tobacco use compromises HIV-associated wellness and liver wellness, and survival. Surprisingly and to date, no study has estimated the prevalence of tobacco use in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection. Empirical data that fills this respective knowledge gap would be advantageous for behavioral health (i.e. clinical psychologists, clinical social workers, psychiatrists, addiction specialists) and public health professionals and liver and infectious disease specialists who provide public health and clinical services to patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of and factors associated with tobacco use among patients living with HCV/HIV co-infection.

Methods

Study Design

This study retrospectively collected and analyzed patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and electronic medical record data of patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection (n = 313) who were receiving ART and in clinical care at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s HIV Clinic from 2015 to 2017. The HIV Clinic provides primary and sub-speciality care to patients living with HIV. When ready for or considering HCV treatment, patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection who received primary care at the HIV Clinic are referred to the HIV/HCV Co-infection Clinic (located within the HIV Clinic). At each clinic visit, patients complete computerized PROs (i.e. validated psychometric scales) on touch-screen tablets. For this study, PROs and electronic medical records data from patients’ first visit with the HIV/HCV Co-infection Clinic were collected and analyzed. The psychometric scales used by the clinic and included in this study are from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) (National Institutes of Health, 2019). This study was approved by the institutional review board at University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Outcomes

The main outcomes of interest were prevalence of tobacco use and factors independently associated with tobacco use among patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection. Two questions from a smoking questionnaire were used (1) to dichotomize patients with and without tobacco use: “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?”, and (2) to assess the number of cigarettes smoked per day: “How many packs of cigarettes do you smoke a day?” (e.g. less than a pack a day, half a pack to 1 a day, between 1 and 2 packs a day, more than 2 packs a day).

Variables

Demographics, Medical Conditions, and Laboratory Values

Data on age, self-reported sex and racial identity, insurance status, HCV and liver-related characteristics, HIV-related characteristics, other medical conditions, and laboratory values were extracted from electronic medical records.

Psychiatric, Alcohol, and Substance Use Disorders

Psychiatric, alcohol, and substance use disorders were extracted from electronic medical records.

Alcohol and Substance Use

Two questions from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) (Bradley et al., 1998; Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998) were used to identify patients with current alcohol use and their amount of use. The following question was used to dichotomize patients who were current users of alcohol and those who were abstainers: “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol (during the past 12 months)?” Patients who endorsed “never” were defined as abstainers of alcohol and those who endorsed “any usage” (e.g. monthly or less, 2–4 times a month, 2–3 times a week, 4–5 times a week, or 6–7 times a week) were defined as current users of alcohol. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) (Newcombe, Humeniuk, & Ali, 2005) was used to identify patients with current substance use. Specifically, the ASSIST assesses current usage of the following illicit substances in the past 3 months: cocaine, amphetamines, street opiates, hallucinogens, inhalants, and non-medical use of cannabis, sedatives or sleeping pills, and prescription stimulants. Patients who endorsed any substance use in the past 3 months were defined as current substance users. Patients who simultaneously endorsed alcohol and substance use on both the AUDIT-C and ASSIST were defined as concurrent users of alcohol and substances.

Depression

Depression was assessed with a 9-item, 4-point Likert scale—The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). The PHQ-9 assesses severity of symptoms of depression. Total scores of 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, and ≥ 20 represent mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.

Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed with a 4-item, 4-point Likert scale—The Patients Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) (Kroenke et al., 2001). Total scores of 0–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12 represent normal, mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively.

Health-Related Quality of Life

The European Quality of Life Five Dimensions (EQ-5D-3L) (Rabin & de Charro, 2001) instrument was used to measure patients’ health-related quality of life. The EQ-5D-3L is composed of two sections: a set of five questions and a visual analogue scale. This study only analyzed the five health-related quality of life questions. The scale assesses health-related quality of life in five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each question uses a 3-point scale: no problems, some or moderate problems, extreme problems. The US population-based EQ-5D index scoring algorithm (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2015) was used to calculate each patients’ EQ index score (i.e. quality of life score). For EQ index scores ranging from 0 to 1, 0 represents worst imaginable health and 1 represents best imaginable health.

Statistical Analysis

Measures of central tendency were used to characterize the sample. Chi-square and the independent samples t-test were used to compare patients with and without tobacco use on dichotomous and continuous variables. Binomial logistic regression was used to identify factors that were independently associated with tobacco use. Analyses were run to avoid multicollinearity in the binomial logistic regression model. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM Corp. Released 2016. SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Results

The mean age of the sample was 53 ± 11.1 years, and the majority of patients were African American (56%) and insured (88%) (Table 1). Patients were aware of their HCV diagnosis for 7 ± 7.3 years, the majority were HCV treatment naïve (i.e. had not ever received treatment for HCV) (88%), and a minority of patients had cirrhosis (13%) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) (3%). Patients were aware of their HIV diagnosis for 14 ± 9.3 years. All patients were actively receiving ART, and patients were on an ART regimen for 11 ± 7.2 years.

The prevalence of tobacco use in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection was 48%. Of those who reported the number of cigarettes smoked per day, 47% and 36% smoked ½ − 1 and 1–2 packs of cigarettes per day, respectively. Compared to those without tobacco use, a higher proportion of those with tobacco use had substance use disorders (29% vs. 44%, p = 0.00), and concurrent alcohol and substance use (21% vs. 40%, p = 0.000) (Table 2). Patients with and without tobacco use did not differ in any other clinical characteristic.

In the multivariate analysis, concurrent alcohol and substance use (OR 3.059, p = 0.011) was positively associated with tobacco use (Table 3).

Discussion

This study utilized outpatient electronic medical record data obtained from a large urban tertiary center to assess prevalence of and factors associated with tobacco use in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection. Several notable findings emerged from this study. First, the prevalence of tobacco use in patients with HIV/HCV co-infection was 48%, and this rate is significantly higher than the national rate (14%) (Creamer et al., 2019). This finding is quite alarming considering the many ways in which tobacco use further amplifies pathophysiological effects of both HIV and HCV. Tobacco use alone in those without HIV or HCV shortens life expectancy by 10 years (Jha et al., 2013), and it is probable that tobacco use in patients with HIV/HCV co-infection further reduces life expectancy. The findings suggest that there is a need for clinical and public health efforts to reduce tobacco use among this doubly-vulnerable immunocompromised population. Otherwise, failed efforts to dedicate resources and targeted interventions for this respective population will inhibit patient survival and achievement of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ national public health goal of reducing and eliminating health disparities and improving the health of all groups as outlined in Healthy People 2020 (Promotion, 2020).

Second, those with concurrent alcohol and substance use were 3.06 times more likely to use tobacco. It has been previously demonstrated that alcohol and substance use in general facilitates uptake of tobacco use (Barrett, Darredeau, & Pihl, 2006; Cohn et al., 2018) and use is positively associated with tobacco use in patients living with HIV mono-infection (Humfleet et al., 2009). Though not well-established in the HIV/HCV co-infection literature, findings from the present study suggest concurrent alcohol and substance use considerably increases the odds of tobacco use in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection. This finding is alarming as well because these multiple agents working in concert (e.g. HIV, HCV, ethanol, and nicotine) exponentially increases the risk for advanced disease complications and death. Equally important, these factors working in concert increases the complexity of patient care for health care practitioners and professionals. As such, an interdisciplinary approach of care (e.g. health care teams made up of liver or infectious disease specialists, clinical social workers, psychiatrists, psychologists, and other behavioral health specialists, and nurses) for patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection may be more ideal than a traditional approach of care (e.g. a single provider or referrals from a single provider to several individual specialists) (Sims, Melton, & Ji, 2018).

To the authors’ knowledge, studies that have investigated effective smoking cessation treatments in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection are limited. However, effective interventions that have been published for use with patients living with HIV include but are not limited to hospital-initiated smoking cessation interventions, pharmacologic agents (e.g. nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, varenicline), smartphone-delivered proactive counselling, motivational interviewing alone and in combination with pharmacologic agents (Calvo-Sanchez & Martinez, 2015; Gritz et al., 2013; Keith, Dong, Shuter, & Himelhoch, 2016; Mercie et al., 2018; Pool, Dogar, Lindsay, Weatherburn, & Siddiqi, 2016; Shuter et al., 2018; Triant et al., 2019; Vidrine, Marks, Arduino, & Gritz, 2012). It is plausible that adaptation and implementation of these respective approaches may also be effective for patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection, but caution must be taken because motivators and factors that drive or facilitate tobacco use in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection have not been fully characterized. Deductive and inductive investigative approaches are needed to acquire a more in-depth understanding of tobacco use in this respective population to identify the most optimal intervention approaches for adaptation and implementation or to develop novel or specialized intervention approaches that may be needed.

Clinical research largely focuses on frequency of alcohol and substance use, harmful effects of alcohol and substance use, and use reduction and cessation among patients living with HIV or HCV. Undoubtedly, attention to both alcohol and substance use are warranted. Alcohol use accelerates HIV and HCV viral replication and worsens liver damage (Lim et al., 2014; Szabo et al., 2010), and both alcohol and substance use reduces medication adherence and increases the risk of transmission to those living without infection (Massa & Rosen, 2012; Sims et al., 2019) Despite tobacco use also expediting HCV and HIV disease progression and other negative health outcomes, tobacco use in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection is rarely addressed in HIV clinical settings and in research. Health professionals and researchers are encouraged to consider intervention approaches that target concurrent alcohol and substance use as a method of reducing the likelihood of tobacco use or intervention approaches that collectively target alcohol, substance, and tobacco use. Intervention approaches that only target tobacco use without regard to alcohol and substance use may be suboptimal.

The study had some noteworthy limitations and strengths. The study was cross-sectional. The study was limited to an analysis of baseline data (e.g. only PRO and electronic medical records data from patients’ first clinic visit) and did not track or collect data on patients’ uptake of HCV treatment. Potentially there are other variables outside of those included in this study that could be associated with tobacco use. The study was limited to a single site and a single state. Multiple racial groups were without representation. Nevertheless, the study sample was comprised of a large number of African American patients. The study used questionnaires with validated psychometric properties. The study sample consisted of patients who had been living with both HIV and HCV for a significant number of years (i.e. were not newly diagnosed patients), were largely insured, were on ART, and actively involved in their HIV care.

Given the recent and evolving COVID-19 pandemic (Huang, Wei, Hu, Wen, & Chen, 2020), efforts are urgently needed—more so now than ever—to identify interventions to assist patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection with smoking cessation. COVID-19 is an opportunistic infection for patients living with weakened immune systems such as HIV and HCV (Felsenstein, Herbert, McNamara, & Hedrich, 2020; Jiang, Zhou, & Tang, 2020), and COVID-19 is quite virulent in patients living with smoking-related respiratory illnesses (Berlin, Thomas, Le Faou, & Cornuz, 2020; Emami, Javanmardi, Pirbonyeh, & Akbari, 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Smoking cessation has the potential to reduce COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality in patients living with HIV/HCV co-infection.

References

Arnson, Y., Shoenfeld, Y., & Amital, H. (2010). Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. Journal of Autoimmunity, 34, J258–J265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003.

Barrett, S. P., Darredeau, C., & Pihl, R. O. (2006). Patterns of simultaneous polysubstance use in drug using university students. Human Psychopharmacology, 21, 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.766.

Bean, M. C., Richey, L. E., Williams, K., Wahlquist, A. E., & Kilby, J. M. (2016). Tobacco Use patterns in a Southern US HIV clinic. Southern Medical Journal, 109, 305–308. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000460.

Berlin, I., Thomas, D., Le Faou, A.-L., & Cornuz, J. (2020). COVID-19 and smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa059.

Bhatta, D. N., Subedi, A., & Sharma, N. (2018). Tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking among HIV infected people using antiretroviral therapy. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 16, 16. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/86716.

Bosh, K. A., Coyle, J. R., Hansen, V., Kim, E. M., Speers, S., Comer, M., …, Hall, H. I. (2018). HIV and viral hepatitis coinfection analysis using surveillance data from 15 US states and two cities. Epidemiology and Infection, 146, 920–930. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818000766

Bradley, K. A., McDonell, M. B., Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., Diehr, P., & Fihn, S. D. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 22, 1842–1849.

Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory care quality improvement project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1789–1795.

Calvo-Sanchez, M., & Martinez, E. (2015). How to Address smoking cessation in HIV patients. HIV Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1111/HIV.12193.

Calvo, M., Laguno, M., Martínez, M., & Martínez, E. (2015). Effects of tobacco smoking on HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Reviews, 17, 47–55.

Cohn, A. M., Johnson, A. L., Rose, S. W., Pearson, J. L., Villanti, A. C., & Stanton, C. (2018). Population-level patterns and mental health and substance use correlates of alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use and co-use in US young adults and adults: Results from the population assessment for tobacco and health. The American Journal on Addictions, 27, 491–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12766.

Creamer, M. R., Wang, T. W., Babb, S., Cullen, K. A., Day, H., Willis, G., …, Neff, L. (2019). Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68, 1013–1019https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2

Cropsey, K. L., Willig, J. H., Mugavero, M. J., Crane, H. M., McCullumsmith, C., Lawrence, S., …, CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. (2016). Cigarette smokers are less likely to have undetectable viral loads: Results from four HIV clinics. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10, 13–19https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000172

Easterbrook, P., Sands, A., & Harmanci, H. (2012). Challenges and priorities in the management of HIV/HBV and HIV/HCV coinfection in resource-limited settings. Seminar of Liver Disease, 2012, 147–157.

Emami, A., Javanmardi, F., Pirbonyeh, N., & Akbari, A. (2020). Prevalence of underlying diseases in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Academic Emergency Medicine, 24, e35–e49.

Feldman, C., & Anderson, R. (2013). Cigarette smoking and mechanisms of susceptibility to infections of the respiratory tract and other organ systems. Journal of Infection, 67, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2013.05.004.

Felsenstein, S., Herbert, J., McNamara, P., & Hedrich, C. (2020). COVID-19: Immunology and treatment options. Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLIM.2020.108448.

Gartner, C., Miller, A., & Bonevski, B. (2017). Extending survival for people with hepatitis C using tobacco dependence treatment. Lancet (London, England), 390, 2033. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32460-1.

Gritz, E. R., Danysh, H. E., Fletcher, F. E., Tami-Maury, I., Fingeret, M. C., King, R. M., …, Vidrine, D. J. (2013). Long-term outcomes of a cell phone-delivered intervention for smokers living with HIV/AIDS. Clinical Infectious Diseases : An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 57, 608–615https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit349

Helleberg, M., Afzal, S., Kronborg, G., Larsen, C. S., Pedersen, G., Pedersen, C., …, Obel, N. (2013). Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1-infected individuals: A nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clinical Infectious Diseases : An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 56, 727–734https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis933

Hézode, C., Lonjon, I., Roudot-Thoraval, F., Mavier, J.-P., Pawlotsky, J.-M., Zafrani, E. S., et al. (2003). Impact of smoking on histological liver lesions in chronic hepatitis C. Gut, 52, 126–129. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.52.1.126.

Huang, X., Wei, F., Hu, L., Wen, L., & Chen, K. (2020). Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of COVID-19. Archives of Iranian Medicine. https://doi.org/10.34172/AIM.2020.09.

Humfleet, G. L., Delucchi, K., Kelley, K., Hall, S. M., Dilley, J., & Harrison, G. (2009). Characteristics of HIV-positive cigarette smokers: A sample of smokers facing multiple challenges. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 21, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.54.

Jha, P., Ramasundarahettige, C., Landsman, V., Rostron, B., Thun, M., Anderson, R. N., …, Peto, R. (2013). 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 341–350https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1211128

Jiang, H., Zhou, Y., & Tang, W. (2020). Maintaining HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet HIV, 20, S2352–3018. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30105-3.

Keith, A., Dong, Y., Shuter, J., & Himelhoch, S. (2016). Behavioral interventions for tobacco use in HIV-infected smokers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 1999(72), 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001007.

Kim, R. S., Weinberger, A. H., Chander, G., Sulkowski, M. S., Norton, B., & Shuter, J. (2018). Cigarette smoking in persons living with hepatitis C: The national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES), 1999–2014. The American Journal of Medicine, 131, 669–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.01.011.

Konopnicki, D., Mocroft, A., de Wit, S., Antunes, F., Ledergerber, B., Katlama, C., …, EuroSIDA Group. (2005). Hepatitis B and HIV: Prevalence, AIDS progression, response to highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased mortality in the EuroSIDA cohort. AIDS (London, England), 19, 593–601

Koziel, M. J., & Peters, M. G. (2007). Viral hepatitis in HIV infection. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356, 1445–1454. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra065142.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Lim, J. K., Tate, J. P., Fultz, S. L., Goulet, J. L., Conigliaro, J., Bryant, K. J., …, Lo Re, V. (2014). Relationship between alcohol use categories and noninvasive markers of advanced hepatic fibrosis in HIV-infected, chronic hepatitis C virus-infected, and uninfected patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases : An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 58, 1449–1458https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu097

Massa, A., & Rosen, M. (2012). The relationship between substance use and HIV transmission in Peru. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000129.

Mercie, P., Arsandaux, J., Katlama, C., Ferret, S., Beuscart, A., Spadone, C., …, Group, A. 144 I.-A. S. (2018). Efficacy and Safety of Varenicline for Smoking Cessation in People Living With HIV in France (ANRS 144 Inter-ACTIV): A Randomised Controlled Phase 3 Clinical Trial. The Lancet HIV, 5, e126–e135https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30002-X

Nahvi, S., & Cooperman, N. A. (2009). Review: The need for smoking cessation among HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 21, 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.14.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US). (2010). How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the surgeon general. Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21452462

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US). (2014). The Health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24455788

National Institutes of Health. (2019). Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Retrieved February 2, 2020, from https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/index

Newcombe, D., Humeniuk, R., & Ali, R. (2005). Validation of the World Health Organization alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): Report of results from the Australian site. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24, 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230500170266.

Pessione, F., Ramond, M. J., Njapoum, C., Duchatelle, V., Degott, C., Erlinger, S., …, Degos, F. (2001). Cigarette smoking and hepatic lesions in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 34, 121–125https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.25385

Petrosillo, N., & Cicalini, S. (2013). Smoking and HIV: Time for a change? BMC Medicine, 11, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-16.

Pool, E. R. M., Dogar, O., Lindsay, R. P., Weatherburn, P., & Siddiqi, K. (2016). Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people living with HIV and AIDS. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011120.pub2.

Promotion, O. of D. P. and H. (2020). Healthy People. Retrieved April 30, 2020, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People

Rabin, R., & de Charro, F. (2001). EQ-5D: A measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Annals of Medicine, 33, 337–343.

Rahmanian, S., Wewers, M. E., Koletar, S., Reynolds, N., Ferketich, A., & Diaz, P. (2011). Cigarette smoking in the HIV-infected population. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, 8, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.201009-058WR.

Re, V. L., Kallan, M. J., Tate, J. P., Localio, A. R., Lim, J. K., Goetz, M. B., …, Justice, A. C. (2014). Hepatic decompensation in antiretroviral-treated patients co-infected with HIV and hepatitis C virus compared with hepatitis C virus–monoinfected patients. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160, 369–379https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1829

Shuter, J., Kim, R. S., An, L. C., & Abroms, L. C. (2018). Feasibility of a smartphone-based tobacco treatment for HIV-infected smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty208.

Shuter, J., Litwin, A. H., Sulkowski, M. S., Feinstein, A., Bursky-Tammam, A., Maslak, S., …, Norton, B. (2016). Cigarette smoking behaviors and beliefs in persons living with hepatitis C. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19, ntw212https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw212

Sims, O. T., Chiu, C.-Y., Chandler, R., Melton, P., Wang, K., Richey, C., et al. (2019). Alcohol use and ethnicity independently predict antiretroviral therapy nonadherence among patients living with HIV/HCV coinfection. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00630-8.

Sims, O. T., Melton, P. A., & Ji, S. (2018). A descriptive analysis of a community clinic providing hepatitis C treatment to poor and uninsured patients. Journal of Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0476-2.

Steel, H. C., Venter, W. D. F., Theron, A. J., Anderson, R., Feldman, C., Kwofie, L., …, Rossouw, T. M. (2018). Effects of tobacco usage and antiretroviral therapy on biomarkers of systemic immune activation in HIV-infected participants. Mediators of Inflammation, 2018, 8357109https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8357109

Strzelak, A., Ratajczak, A., Adamiec, A., & Feleszko, W. (2018). Tobacco smoke induces and alters immune responses in the lung triggering inflammation, allergy, asthma and other lung diseases: A mechanistic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15051033.

Szabo, G., Wands, J. R., Eken, A., Osna, N. A., Weinman, S. A., Machida, K., et al. (2010). Alcohol and hepatitis C virus–interactions in immune dysfunctions and liver damage. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 1675–1686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01255.x.

Taylor, L. E., Swan, T., & Mayer, K. H. (2012). HIV coinfection with hepatitis C virus: Evolving epidemiology and treatment paradigms. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 55, S33–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis367.

Teira, R. (2013). Hepatitis-B virus infection predicts mortality of HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. AIDS, 27, 845–848. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ecaf7.

Tesoriero, J. M., Gieryic, S. M., Carrascal, A., & Lavigne, H. E. (2010). Smoking among HIV positive New Yorkers: Prevalence, frequency, and opportunities for cessation. AIDS and Behavior, 14, 824–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9449-2.

Thein, H.-H., Yi, Q., Dore, G. J., & Krahn, M. D. (2008). Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected individuals and the impact of HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England), 22, 1979–1991. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e6d51.

Triant, V. A., Grossman, E., Rigotti, N. A., Ramachandran, R., Regan, S., Sherman, S. E., …, Harrington, K. F. (2019). Impact of smoking cessation interventions initiated during hospitalization among HIV-infected smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobaccohttps://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz168

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2015). Calculating the U.S. Populatoin-based EQ-5D Index Score. Retrieved March 17, 2018, from https://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/resources/rice/EQ5Dscore.html

Vidrine, D. J., Marks, R. M., Arduino, R. C., & Gritz, E. R. (2012). Efficacy of cell phone-delivered smoking cessation counseling for persons living with HIV/AIDS: 3-month outcomes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 14, 106–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr121.

Zhao, L., Li, F., & Taylor, E. W. (2013). Can tobacco use promote HCV-induced miR-122 hijacking and hepatocarcinogenesis? Medical Hypotheses, 80, 131–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2012.11.009.

Zhao, Q., Meng, M., Kumar, R., Wu, Y., Huang, J., Lian, N., …, Lin, S. (2020). The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of Covid-19: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Virology. https://doi.org/10.1002/JMV.25889

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Grant R25DA028567 to Omar T. Sims and under Grants R25DA035163 and T32DA007238 to Asti Jackson. The study sponsor had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: [OTS and AJ]; Methodology: [OTS, AJ, YG]; formal analysis and investigation [OTS, YG, and DNT]; Writing-original draft preparation: [OTS, AJ, EAO, and HMM]; Writing-review and editing [OTS, AJ, YG, DNT, EAO, and HMM]; Funding acquisition [OTS and AJ]; Resources [OTS]; Supervision [OTS].

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Omar T. Sims, Asti Jackson, Yuqi Guo, Duong N. Truong, Emmanuel A. Odame and Hadii M. Mamudu declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This research study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. We consulted extensively with the IRB of the University of Alabama at Birmingham who determined that our study did not need ethical approval. An IRB official waiver of ethical approval was granted from the IRB of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Informed Consent

The study was a retrospective analysis of de-identified secondary data. The IRB at the University of Alabama at Birmingham deemed the study exempt from informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sims, O.T., Jackson, A., Guo, Y. et al. A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Tobacco Use and Concurrent Alcohol and Substance Use Among Patients Living with HIV/HCV Co-infection: Findings from a Large Urban Tertiary Center. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 28, 553–561 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09744-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09744-2