Abstract

Although research has long examined applicants’ use of impression management (IM) behaviors in the interview, interviewers’ IM has only been recently investigated, and no research has attempted to combine both. The aim of this research was to examine whether and how applicants and interviewers adapt their IM to one another. To answer this question, we bring together IM, signaling theory, and the concept of adjacency pairs from linguistics, and carried out two studies. Study 1 was an observational study with field data (N = 30 interviews including a total of 6290 turns of speech by interviewers and applicants). Results showed that both applicants and interviewers are more likely to engage in IM in a way that can be considered as a “preferred” (vs. “dispreferred”) response pattern. That is, self-focused IM is particularly likely to occur as a response to other-focused IM, other-focused IM as a response to self-focused IM, and job/organization-focused IM as a response to job/organization-focused IM. In study 2, we used a within-subjects design to experimentally manipulate interviewer IM and examine its impact on (N = 120) applicants’ IM behaviors during the interview. Applicants who engaged more in “preferred” IM responses were evaluated as performing better in the interview by external raters. However, “preferred” IM responses were not associated with any other interview outcomes. Altogether, our findings highlight the adaptive nature of interpersonal influence in employment interviews, and call for more research examining the dynamic interactions between interviewers and applicants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The employment interview is a high-stakes interpersonal interaction wherein all parties can benefit from making a positive impression. To do so, applicants (Bourdage, Roulin, & Tarraf, 2018) and interviewers (Wilhelmy, Kleinmann, König, Melchers, & Truxillo, 2016) use impression management (IM)—defined as conscious or unconscious attempts to influence images during a social interaction (Schlenker, 1980). For example, applicants often use self-focused IM (e.g., using self-promotion to present their qualifications in a positive light) to signal relevant work experience and competencies (Stevens & Kristof, 1995). Similarly, interviewers often use other-focused IM—such as praising applicants’ experiences—to signal likability, as well as organization-focused IM—such as promoting company benefits or organizational culture—to signal prestige or status (Tsai & Huang, 2014). Existing research suggests that IM use can lead to positive interview outcomes on both sides of the interview table; that is, applicants increase their chances of getting a job offer and organizations increase their chances of filling a position (e.g., Barrick, Shaffer, & DeGrassi, 2009; Wilhelmy, Kleinmann, Melchers, & Götz, 2017).

Past research has focused on individual differences (e.g., personality) or situational factors (e.g., interview format) as antecedents of IM use, but interviewers and applicants are also likely to adapt their IM according to new information communicated (i.e., signals sent and received) during the interview (Bangerter, Roulin, & König, 2012). Adaptation can be defined as the process of achieving fit between new demands and individual behavior (Chan, 2000). Similarly, adaptive performance refers to a change in response to an altered situation (Dorsey, Cortina, & Luchman, 2010). For instance, an interviewer might praise an applicant (i.e., use other-focused IM) as a recruitment strategy, and the applicant might adapt by building on the interviewer’s praise and stressing their accomplishments (i.e., use self-focused IM). As Dipboye, Macan, and Shahani-Denning (2012) point out, “there is a give and take that has been largely ignored in the selection interview research” (p. 341). Particularly, empirical research has largely ignored the potential interaction of IM behaviors across roles. The aim of our research was thus to examine whether and how applicants and interviewers adapt their IM to one another.

In study 1, we analyzed interviews from real selection settings. Interviews were transcribed and applicant and interviewer IM were coded for each turn of speech to analyze patterns of adaptation between consecutive turns of speech. In study 2, we used a within-subjects design and experimentally manipulated interviewer IM to examine its causal effect on applicant IM in terms of within-applicant variability in IM during the interview in response to changes in interviewer IM. We further video recorded the interviews, coded applicant IM, and obtained outcome measures from applicants, interviewers, and observers to additionally examine whether patterns of applicants’ IM adaptation relate to various interview outcomes such as positive affect, interviewer liking towards the applicant, and interview performance.

Our research contributes to the IM and interview literatures in several important ways. First, the employment interview is a “dyadic interaction, akin to a dance” (Dipboye et al., 2012, p. 341) in which it takes both parties—interviewers and applicants—to tango. In other words, interviewers’ and applicants’ behaviors are by definition understood to be essential in the interview and theoretically interdependent (e.g., Bangerter et al., 2012; Macan, 2009). However, research has not investigated how interviewer and applicant IM influence each other, and how one party’s IM can lead to the other party’s IM. Our research thus breaks new ground in the IM and interview literature by describing interviewers’ and applicants’ use of IM not only as influenced by individual differences or the interview format, but also as an essential component of the adaptive interview “dance.”

Second, in order to examine patterns of IM adaptation, we bring together the principles of adaptations and counter-adaptations from signaling theory (Bangerter et al., 2012; Spence, 1973) and the linguistic concept of adjacency pairs (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1978). Bringing together those two frameworks offers a deeper, micro-level understanding of influence behaviors and signaling in the employment interview. Acknowledging the role of language also opens the door to new ways of examining interactions in the selection context in future research.

Third, we do not only examine how interviewers and applicants adapt their IM to one another, but also explore potential effects on interview outcomes. Although research has shown that the more applicants use IM (e.g., self-promote) the better they are evaluated by interviewers (Barrick et al., 2009), it remains unclear whether applicants and interviewers benefit from using more IM or more of the “right” IM responses to their interaction partner. Indeed, in the adjacency pair literature, a preferred response in a conversation involves agreeing with, and building on, previous statements made by the interaction partner. Similarly, applicants and interviewers engaging in preferred IM responses, such as building on the self-promotion or praise of the other party, could lead to more satisfactory interactions, and positively influence outcomes that are of practical importance to applicants and organizations, such as performance ratings or organizational attractiveness. Alternatively, the overall amount of IM used throughout the interview could remain the most important influencing factor for interview outcomes.

Signaling Theory, Impression Management, and Adaptation

In a theoretical paper, Bangerter et al. (2012) argued that the selection process can be conceptualized as a signaling game, whereby both applicants and organizations (or their representatives, such as interviewers) exchange and interpret signals about each other’s qualities and commitment towards a potential employment relationship. In an employment interview, applicants attempt to signal that they are qualified to perform the duties of the job and a good fit with the hiring organization in terms of values or culture. Interviewers receive and interpret these signals in order to assess the degree of each applicant’s suitability (Spence, 1973). But interviewers also send signals to applicants, for instance, by informing them about the advantages of working for their organization (e.g., compensation, benefits, development opportunities, culture). Applicants in turn receive, interpret, and use this information to decide whether to accept a job offer. In sum, the interview can be conceptualized as a dynamic interaction in which a series of signals are sent and interpreted by both parties. In addition, Bangerter et al. (2012) argue that relationships between applicants and organizations (or interviewers) are, by nature, adaptive. In other words, applicants and interviewers use the information they have gathered and adapt their behaviors (i.e., the signals they send) accordingly. Adaptations can take place across multiple interactions, for instance, when applicants use the outcome of one interview and the feedback received to adapt their behaviors in subsequent interviews (Roulin, Krings, & Binggeli, 2016). Adaptations can also take place within one interaction, for instance, when applicants use the information provided by the interviewer to adapt the content of their next response.

Signaling theory has repeatedly been applied in recruitment research. For instance, Suazo, Martínez, and Sandoval (2009) described the means by which HR practices are interpreted as signals, for example, by applicants. In addition, Connelly, Certo, Ireland, and Reutzel (2011) developed a theoretical synthesis of the signaling process that particularly emphasizes that signaling does not stop when a signal is received. Instead, the authors argue, the receiver also reacts to the original signal such that a feedback loop informs the sender that the signal was received. Walker et al. (2013) further showed that correspondence delivered to applicants (e.g., emails) conveyed justice signals to applicants (i.e., applicants made justice evaluations based on the correspondence), which influenced their uncertainty, and ultimately altered their assessment of organizational attractiveness. Building on these findings, we anticipate that applicants and interviewers interpret signals in the interview and adapt their behaviors accordingly in order to achieve their desired image.

Research suggests that applicants and interviewers rely on a variety of IM tactics to ensure that they create the best possible impression. For instance, applicants can engage in self-focused IM tactics such as self-promotion to best promote their skills, abilities, and work experiences, or other-focused tactics such as ingratiation to praise the interviewer or hiring organization (e.g., Bourdage et al., 2018; Stevens & Kristof, 1995). Similarly, interviewers can engage in self-focused IM (demonstrating their expertise and professionalism), job/organization-focused IM (praising the team the applicant would join or framing the organization positively), or other-focused IM (expressing their knowledge of the applicants’ file, Wilhelmy et al., 2016).

Interestingly, existing IM research has examined applicant IM and interviewer IM separately, and no study has investigated how the two interact. Moreover, examinations of why and how much applicants engage in IM have been largely limited to factors such as individual differences or interview format (e.g., Peeters & Lievens, 2006; Roulin & Bourdage, 2017; Van Iddekinge, McFarland, & Raymark, 2007). Yet, if IM tactics are indeed incorporated in a dynamic exchange of signals during the interview (Bangerter et al., 2012), applicants’ and interviewers’ use of IM should be interdependent. For example, the type of IM used by the applicant should depend on the type of IM used by the interviewer, and vice-versa. In other words, if behaviors during the selection process are indeed adaptive (Bangerter et al., 2012), applicants and interviewers should adapt the types of IM they use (e.g., self- vs. other- vs. job/organization-focused tactics) in order to send the best possible signal at a specific moment during the interview. Although signaling theory explains why applicants and interviewers should adapt their behaviors, it remains silent on the optimal way to do it. We argue that the best signal likely depends on the exchange of information preceding that moment, particularly whether applicants and interviewers build on the IM that the interaction partner used in the preceding turn of speech. Such an argument is derived from conversation analysis, which we describe in the next section.

Using Conversational Turn-Taking to Examine IM Patterns

There have been repeated calls to advance our understanding of interview processes and IM by bringing together IM and linguistic approaches such as conversation analysis (Holtgraves, 2002). For example, Tullar (1989b) pointed out that “if investigators are ever to get a handle on the interview process, careful study of the sequence of interview behaviors, utterance by utterance, interaction by interaction…must be done” (p. 977). Similarly, Holtgraves (2010) points out that “both impression management and person perception are grounded in verbal interactions, and there is much to be gained by examining the role of language use in these processes” (p. 1412). The main reason for these calls is that any human conversation follows certain patterns. Particularly, people take turns when speaking. As a consequence, what we say is constrained by what our conversation partner just said (Holtgraves, 2002). With regard to IM, this suggests that the type of IM that applicants and interviewers use, when they use it, and how effective it is (i.e., to create a positive impression on the interviewer or make the applicant more attracted to the job/organization) might depend on the IM that their interaction partner used in their preceding turn of speech.

In a conversation—for example, a job interview—the smallest structural unit contains two turns of speech by two speakers, one after the other, which is referred to as an adjacency pair (Sacks et al., 1978). Importantly, in an adjacency pair, the second speaker is constrained by what the first speaker has said. For example, an assessment or statement usually evokes agreement because it displays understanding, appreciation, and acceptance of what has just been said. According to conversation analysis, agreeing with, and building on, previous statements is a preferred response (making the conversation more focused) whereas disagreeing and ignoring previous statements is a so-called dispreferred response (possibly causing stagnation of the conversation). Preferred responses such as showing agreement are expected in human interactions. Failing to provide the preferred response (e.g., not building on the previous turn of speech) can be perceived as boorish or rude (Holtgraves, 2002).

In the interview context, applicants and interviewers engage in IM with a specific focus (e.g., themselves, their interaction partner, or the organization) and a specific goal (e.g., praise, defend, criticize) in mind. According to the concept of adjacency pairs, applicants and interviewers should tend to use the kind of IM that builds on their interaction partner’s IM (i.e., a “preferred” IM response). For example, when the interviewer is praising the organization (e.g., “our culture is unique because we place employees first”), the preferred response from the applicant would be to build on this praise and use organization-focused IM as well (e.g., “this seems like a wonderful place to work”), thus keeping the organization as the focus. In contrast, a dispreferred response would involve switching the focus of the conversation (e.g., engage in self-focused or other-focused IM), and might frustrate the interviewer. Similarly, when the interviewer uses self-focused IM, the preferred response from the applicant would be to keep the interviewer as the focus by using other-focused IM. Following the same pattern, other-focused IM by the interviewer would evoke self-focused IM in the applicant so that the applicant remains the focus. The same mechanisms apply when interviewers adapt to applicants’ IM. For instance, if an applicant engages in self-focused IM (e.g., highlighting their qualifications for the job), the preferred response from the interviewer would be to engage in other-focused IM (e.g., acknowledge or praise the applicant’s qualifications).

An alternative response pattern would be interaction partners mirroring each other’s IM, that is, using the exact same IM behavior (e.g., applicant self-focused IM following interviewer self-focused IM). However, although past research has revealed that nonverbal mirroring can have positive effects, switching the focus of the conversation (which is in line with dispreferred responses of the adjacency pair concept) can be perceived unfavorably in conversations. For example, analyses of police officer-citizen interactions showed that mirroring or symmetrical interaction (i.e., each party emphasizing themselves to gain control of the situation) was experienced as dissatisfying (Glauser & Tullar, 1985). Given humans’ tendency to build on preceding information and keep the focus of the interaction constant as expressed by the adjacency pairs concept, we hypothesized that applicants’ and interviewers’ IM follows specific patterns of preferred IM responses. Specifically,

-

Hypothesis 1: With regard to patterns of IM, (a) applicants use more self-focused IM following interviewers’ use of other-focused IM and (b) interviewers use more self-focused IM following applicants’ use of other-focused IM.

-

Hypothesis 2: With regard to patterns of IM, (a) applicants use more other-focused IM following interviewers’ use of self-focused IM and (b) interviewers use more other-focused IM following applicants’ use of self-focused IM.

-

Hypothesis 3: With regard to patterns of IM, (a) applicants use more job/organization-focused IM following interviewers’ use of job/organization-focused IM and (b) interviewers use more job/organization-focused IM following applicants’ use of job/organization-focused IM.

Study 1

In study 1, we investigated the natural occurrence of applicants’ and interviewers’ IM adaptations in the field using transcribed interviews from real selection settings in order to test hypotheses 1 to 3. More precisely, we coded interviewer and applicant IM during each turn of speech within each interview, and analyzed the patterns of specific applicant and interviewer IM behaviors in response to their counterpart’s IM behaviors, in two adjacent turns of speech. We focused on within-interview conversational turns and analyzed 30 interviews with N = 6290 turns of speech.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We audio-recorded (and later transcribed) 30 real job interviews, a number similar to past research focusing on a fine-grained analysis of turns of speech (Glauser & Tullar, 1985; Tullar, 1989b). Applicants were 28 senior business students from a Canadian university business program interviewing for a 4-month paid co-operative work placement. Two of the applicants participated in two different interviews. Interviews ranged from 30 to 60 min. A one-page instruction sheet and a digital recorder were installed in each interview room. Both interviewers and applicantsFootnote 1 consented to be recorded and were blind to the hypotheses.

Coding Procedures

Transcripts were tabulated into chronological turns of speech and coded for IM behaviors. Our IM coding system was designed based on Ellis, West, Ryan, and DeShon (2002) and expanded based on insights from Wilhelmy et al. (2016) to also acknowledge the interviewers’ perspective. We followed procedures from past research (Ellis et al., 2002; McFarland, Yun, Harold, Viera, & Moore, 2005; Peeters & Lievens, 2006; Stevens & Kristof, 1995; Wilhelmy et al., 2017) to code IM as self-focused, other-focused, and job/organization-focused. Self-focused IM included statements promoting oneself such as statements about one’s skills, competences, or experiences (e.g., “I have a lot of work experiences as far as human resource” from the applicant, “I’ve been the marketing coordinator for four years now” from the interviewer); other-focused IM included statements promoting one’s interaction partner(s) such as statements about the similarity between oneself and the interaction partner(s) or praising the partner(s) (e.g., “Cool, that’s great that you have done that” from the applicant, “Your enthusiasm is there, that’s for sure” from the interviewer); organization-focused and job-focused were later combined into job/organization-focused IM and included statements promoting the job/organization such as statements about the qualities of the organizations and the fit or attraction between oneself and the job/organization (e.g., “This is a big firm, so that’s gonna make this job dynamic” from the applicant, “We have a hundred and thirty year history, we have two offices” from the interviewer). Following the procedure of Ellis et al. (2002), the third author trained two research assistants who were blind to the hypotheses and tested inter-rater reliability from a subsample of transcript excerpts (i.e., sections including a few interactions between applicants and interviewers). Specifically, the third author coded three transcripts, and used one of these transcripts as an exemplar to introduce two research assistants to the transcript data and to provide examples of how the data could be coded for IM. From the other two transcripts, five excerpts were drawn to use for inter-rater reliability testing. These five excerpts, approximately one page long each, were coded for IM independently by the third author and the two research assistants. To improve consistency among raters, discrepant codes were discussed after coding each excerpt. To avoid inflating reliabilities, these codes were kept discrepant for the reliability calculation. Inter-rater reliability was computed based on each rater’s total number of each of the four IM types across all five excerpts. Reliability was good, ICC2 = 0.90, so the remainder of the transcripts was coded individually.

Next, all transcripts were organized into chronologically numbered turns of speech (i.e., each turn started in a new line and all turns were chronologically numbered). A turn of speech is a unit of analysis based on the period of time when a speaker is talking during a conversation; that is, it starts when the person (applicant or interviewer) starts to talk and ends when the other party takes over the conversion. For instance, an interviewer asking a question and an applicant providing a response would represent two adjacent turns of speech. Similarly, an applicant talking about themselves and an interviewer then commenting on it would also represent two adjacent turns of speech. For interviews containing more than one interviewer (i.e., 26 out of the 30 interviews), all interviewers were treated as a single conversational member. This had two repercussions. First, multiple consecutive turns of speech among interviewers were recorded as a single turn. Second, if an interviewer complimented another interviewer, this was coded as self-focused IM. Tabulating the transcripts in this way ensured that turns of speech always alternated between interviewer and applicant, allowing an exploration of the adaptation of IM behaviors across roles, over time.

Results

Notably, turns of speech do not always include IM.Footnote 2 As we investigate the interaction of IM across turns (i.e., agency pairs), Table 1 shows the average number and proportion of two-turn speech patterns that include IM in both turns. Only 12% of two-turn speech patterns included IM in both turns, but this represents an average of 23 instances per interview. In addition, even relatively scarce behaviors can lead to important theoretical insights and have strong effects on interview outcomes (e.g., extensive image creation, Levashina & Campion, 2007).

Descriptive statistics for the frequencies of applicant IM following interviewers’ IM, and interviewer IM following applicants’ IM, in adjacent turns of speech across all interviews are presented in Table 2. To examine patterns of preferred IM responses, we computed χ2 tests comparing the sum of self-focused, other-focused, and job/organization-focused IM behaviors to the sum of all other IM behaviors, respectively, when following a counterpart’s (interviewer’s or applicant’s) self-focused, other-focused, or job/organization-focused IM behaviors (Table 3). Where significant, the χ2 test suggests a preference (or avoidance) of one IM behavior, relative to all alternative IM behaviors, in response to a counterpart’s specific IM behavior. These χ2 results were followed up with odds ratios to illustrate the direction and size of effects.

In line with hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a, all three χ2 tests for the patterns of preferred applicant IM response to interviewer IM were significant, and odds ratios were all in expected directions. This means that preferred IM responses were significantly more likely to be used than dispreferred IM responses. Specifically, applicants were 1.96 times more likely to use other-focused IM when the interviewer used self-focused (compared to other types of) IM, 3.64 times more likely to use self-focused IM when the interviewer used other-focused (compared to other types of) IM, and 4.08 times more likely to use job/organization-focused IM when the interviewer used job/organization-focused (compared to other types of) IM.

Regarding H1b, H2b, and H3b, for interviewer responses, only one of three χ2 tests of preferred IM response patterns was significant. In line with H2b, interviewers were 6.52 times more likely to use other-focused IM when the applicant used self-focused (compared to other types of) IM. The other two response patterns were only marginally significant (p = 0.079 and 0.055, respectively), thus offering only partial support for H1b and H3b, but the patterns were in the hypothesized direction. Interviewers were 1.80 times more likely to use self-focused IM when the applicant used other-focused (compared to other types of) IM, and 2.14 times more likely to use job/organization-focused IM when the applicant used job/organization-focused IM.Footnote 3

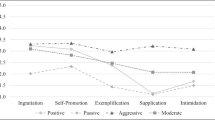

We additionally explored the potential role of interview structure. Based on Chapman and Zweig’s (2005) interview structure measure, we coded the level of interview structure in the transcripts (i.e., low-, medium-, and high-structure). We used visible indicators of structure highlighted in the literature, such as the presence of a rapport-building stage, the level of job-relevance of interview questions, or the use of probing and follow-up questions (e.g., Levashina, Hartwell, Morgeson, & Campion, 2014). We then graphed applicants’ and interviewers’ average use of preferred and dispreferred IM responses across the three levels of structure (see Fig. 1 in the Appendix and additional information in the Open Science Repository). Overall, patterns of both preferred and dispreferred IM were more frequent in less structured (vs. more structured) interviews.

Discussion

Results of study 1 showed that interaction partners (i.e., applicants and interviewers) adapted their IM to each other in patterns of preferred responses. These results are generally consistent with signaling theory (Bangerter et al., 2012; Spence, 1973) and the linguistic concept of adjacency pairs (Sacks et al., 1978). This first study thus offers initial insights into the patterns of applicants’ and interviewers’ IM adaptation as part of the signaling game inherent in employment interviews. However, it also suggests that applicants adapt more to interviewer IM than the other way around. Such effect could be explained by the relative power difference between the two interaction partners. Indeed, in most interviews, interviewers are in a position of power (i.e., having the ability to make a job offer to one of several applicants) and may thus be less pressured to engage in preferred IM adaptations. In contrast, applicants might be more pressured to adapt to the interviewer by using preferred IM responses. This was the case in the context of study 1, with business students interviewing for competitive co-op placement positions. However, there are situations where the power balance can switch in favor of applicants (e.g., low unemployment, uniquely qualified applicant). Additional analyses also suggested that using more structured formats might limit both applicants’ and interviewers’ opportunity to engage in patterns of preferred IM in the interview. This is consistent with arguments from the structured interview literature (e.g., Levashina et al., 2014) presenting structure as a shield against IM. Indeed, many structure components (e.g., limiting rapport-building, probing, or applicant questions) reduce opportunities for both applicants and interviewers to engage in IM and thus also in preferred IM patterns.

Importantly, these initial results are based on several thousand speech instances from transcripts of actual interviews. The use of field data thus enhances the generalizability and ecological validity of our findings. However, this first study has a number of limitations. It is based on a small set of interviews. Interviews were also largely heterogeneous in format (e.g., various levels of interview structure, different durations) and content (e.g., quality of interviewers’ questioning). This made the examination of specific preferred patterns of IM more difficult. Furthermore, we could not systematically examine changes in IM types during the interview in response to changes in the preceding type of IM. In addition, this first study did not allow us to explore whether the use of preferred patterns of IM impacts interview outcomes, which we discuss below and examine in our second study.

IM Adaptation Patterns and Interview Outcomes

The adjacency pair concept is useful for exploring whether patterns of preferred IM adaptation have an influence on interview outcomes. It proposes that preferred responses increase the comfort experienced by interacting individuals, while dispreferred responses lead to disagreement or rejection (Holtgraves, 2010). Adapting to and affirming one’s interaction partner tends to produce harmony and thus leads to more satisfaction and liking for interaction partners (Sadler, Ethier, & Woody, 2011). Based on these theoretical considerations, applicants should experience more of a conversational flow and thus have more positive feelings after the interview. Similarly, interviewers should also experience more harmonic, flowing conversation and should thus have more positive affects towards the applicant. In addition, early interview research has shown that building on preceding interviewers’ arguments made applicants appear more confident, and such a pattern was more frequent in successful interviews (vs. unsuccessful interviews, Einhorn, 1981). As such, patterns of preferred IM might be associated with higher interview performance.

However, the use of IM in itself should evoke favorable responses because it communicates positive, desirable information (e.g., praising one’s own qualities, one’s interaction partner’s qualities, and the job’s or organization’s qualities). Thus, even if dispreferred responses can be frustrating, such negative reactions are likely to be mild when it comes to IM. In addition, study 1 suggested that there are less pairs of adjacent turns containing IM than single turns containing IM, which could imply that the overall amount of IM used throughout the interview might have a stronger influence on interview outcomes than preferred responses in particular. And, indeed, past research suggests that IM use is in itself associated with positive interview outcomes (e.g., Barrick et al., 2009). Hence, it is important to examine the potential incremental effects of applicants’ preferred IM adaptations on interview outcomes, above and beyond applicants’ IM use. More precisely, we expected that responses categorized as “preferred” (i.e., self-focused IM in response to other-focused IM, other-focused IM in response to self-focused IM, and job/organization-focused IM in response to job/organization-focused IM) would be associated with positive affective responses, liking, and performance ratings from interviewers, observers, and independent raters beyond the overall amount of applicants’ IM use:

-

Hypothesis 4: The more applicants adapt their IM to the interviewer’s IM in patterns of preferred responses, (a) the more they report positive affect after the interview, (b) the more they are liked by the interviewer, (c) the higher their overall performance as rated by interviewers and observers, and (d) the higher their performance as rated by independent raters using behaviorally anchored rating scales (BARS) beyond the influence of the amount of IM that applicants use.

Study 2

In study 2, our aim was to have an even closer look at IM adaptations by examining whether the preferred patterns found in study 1 can also be evoked through experimental manipulation, and whether preferred patterns of IM adaptation relate to interview outcomes. For this purpose, we focused on one direction of IM exchange—applicants adapting their IM to the interviewer’s IM—across two turns of speech. This focus was in line with our findings in study 1 where evidence of interviewer-applicant patterns was stronger than for applicant-interviewer patterns. In addition, it enabled us to systematically manipulate interviewer IM during a simulated interview to investigate changes in applicant IM in response to changes in interviewer IM. We used an experimental within-subjects design to examine the causal effect of interviewer IM on applicant IM in terms of within-applicant variation in IM evoked by variation in interviewer IM. We again predicted that applicants would adapt their IM to the interviewer’s IM by using preferred patterns (providing a more precise test of hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a). In addition, we explored whether such patterns of preferred IM adaptation would impact interview outcomes (hypothesis 4a–d).

Method

Participants

Participants were 120 individuals who were interested in getting feedback on their performance in a practice employment interview. We used flyers, postings on social media, and mailing lists of several Swiss university career services and alumni groups to contact individuals who were currently (or would soon be) applying for jobs. Individuals were only allowed to participate if they were proficient in German (as interviews were conducted in German) and were employed at least part-time at the time of the study. As an incentive for participation, we offered individual oral feedback on participants’ resumes and interview behavior after the interview. In addition, participants were informed that the person with the highest interview performance score would receive a gift card (equivalent to $85) for a food delivery service.

We were contacted by 340 people interested in participating in this study, but 134 did not fulfill the criteria for participation, 82 participants did not sign up bindingly for an interview date, two participants’ interviews were incomplete because interview questions had been skipped by accident, and two participants’ interviews were not video recorded because the camera had inadvertently not been turned on. This resulted in a final sample of 120 participants. Participants’ mean age was 25.48 years (SD = 3.19) and 48.33% were female. All participants were pursuing a university degree (67.50% graduate students, 32.50% undergraduate students). They came from a variety of majors, including psychology (12.50%), mechanical engineering (10.83%), and chemistry (6.67%). All participants were employed and were working, on average, 21.47 h per week (SD = 14.28 h), with about 54% of the participants working in research and education, 12% in services, or 6% in sales and distribution. Participants had participated in an average of 6.33 interviews (SD = 7.00) in their lives and had an average of 3.79 years of work experience (SD = 3.12). The majority of participants (67.50%) were Swiss, 25.00% were German, and 7.50% had other nationalities. All participants were blind to the study hypotheses.

Procedure and Design

Participants were asked to imagine applying for a job as a trainee in a technology company. As a first step, participants received an email with a job ad and an excerpt of the website of a fictitious company describing the organization and the interviewer. In addition, participants were asked to complete an online survey including demographic questions and to submit their resume. The practice employment interviews were conducted by one of two Human Resources professionals with a Bachelor’s degree in I/O psychology (one male, one female) who were blind to the hypotheses. Both interviewers wore formal dress (white button-down shirt or blouse, gray blazer, black horn-rimmed glasses). In addition, both interviewers were trained to follow the interview script (which included our manipulation of interviewer IM, see Open Science Repository) and to use nonverbal behavior sparingly and in a similar fashion. The two interviewers did not differ significantly in how pleasant they were perceived by participants, t(118) = 0.09, p = 0.403.

The interview protocol consisted of four different parts, three of which featured our manipulation of interviewer IM type (i.e., self-focused, other-focused, or job/organization-focused IM) plus a baseline condition (in which the interviewer simply skipped the interviewer IM sequences and only asked the interview questions). Each part started with a sequence of interviewer IM (or nothing in the baseline condition) followed by an interview question, a second sequence of the same kind of interviewer IM, followed by another interview question. Applicants were given the opportunity to respond after both the IM sequences and the interview questions. In other words, each interview included 14 turns of speech by the interviewer (6 IM sequences and 8 questions) and 14 turns of speech by the applicant (6 responses to the interviewer IM and 8 responses to interview questions). The interview questions consisted of four past-behavior and four future-oriented questions covering two dimensions (persistence and organizing behaviors) that have been used and validated in past research (Ingold, Kleinmann, König, & Melchers, 2015). The order of the interviewer IM sequences was counterbalanced across interviews, resulting in 16 different versions of the interview protocol (see Table 10 in the Appendix).

In order to create interviewer IM scripts that were both realistic and aligned with the existing IM literature, we conducted a pre-test with 25 subject matter experts (SMEs): 11 researchers with expertise in IM and employment interview research and 14 practitioners with expertise in human resources. SMEs completed an online survey in which they were presented with the six text segments of interviewer IM manipulations (two text segments for each interviewer IM condition). For each segment, SMEs were asked to indicate whether the text represented self-focused, other-focused, or job/organization-focused interviewer IM. All segments were assigned to the correct IM category by all SMEs. In addition, SMEs were asked to comment on the external validity of the interviewer IM manipulation and to suggest improvements. Overall, external validity was rated highly. The wording of some of the text segments was revised based on the SMEs’ recommendations to further ensure external validity.

On average, the interviews were 20.73 min long (SD = 4.51), which resulted in about 42 h of video material. After the interview, participants completed a measure of positive affect. Furthermore, interviewers completed a measure assessing the degree to which they liked the applicant and an overall measure of applicant interview performance. In addition, observers evaluated the applicant based on the video recordings.

Measures

Amount of Applicant IM

Our coding scheme, coding rules, and coder training for assessing applicant IM were in line with study 1 and analogous to previous studies on IM in employment interviews (Ellis et al., 2002; McFarland et al., 2005; Peeters & Lievens, 2006; Stevens & Kristof, 1995; Wilhelmy et al., 2017). One I/O graduate student and one I/O undergraduate student served as raters (see Table 11 in the Appendix for an overview of all raters involved in study 2). Both raters were blind to the hypotheses. They each participated in a half-day frame-of-reference training (Bernardin & Buckley, 1981) before coding applicant statements into the three different types of applicant IM: self-focused IM (e.g., “I’m goal-oriented”), other-focused IM (e.g., “I find it remarkable how much expertise you have”), or job/organization-focused IM (e.g., “I am impressed by your company”). Raters used the INTERACT video coding software (version 9, Mangold, 2010) which allows coding the frequency of statements or behaviors. Raters were blind to the conditions and hypotheses and were only shown the video sections that they needed to code applicant IM. They watched the video recording of an interview and upon identifying one of the three types of applicant IM, they pressed a key programmed to represent that specific type. The frequency of applicant IM (i.e., amount of IM across the interview) was assessed based on the number of keystrokes for each type. After the frame-of-reference training, video recordings of 15 interviews were coded independently by each rater. The level of interrater reliability was good, ICC2,1 = 0.92 (Cicchetti, 1994; LeBreton & Senter, 2008), so the rest of the 105 interviews were split between the two raters.

Ratio of Preferred IM Adaptation

To assess the degree to which applicants adapted their IM to the interviewer’s IM in a pattern of preferred responses (i.e., using self-focused IM in response to interviewers’ other-focused IM, other-focused IM in response to interviewers’ self-focused IM, and job/organization-focused IM in response to interviewers’ job/organization-focused IM), we looked at each kind of applicant IM separately and when (i.e., in which interviewer IM condition) this kind of IM was used most (i.e., we examined the frequencies of each type of applicant IM across the interviewer IM conditions). More precisely, for each applicant, we calculated the percentage of one kind of IM (e.g., other-focused applicant IM) used as a preferred response (i.e., used in response to self-focused interviewer IM vs. in response to other-focused or job/organization-focused interviewer IM). For example, if an applicant used other-focused IM seven times in response to self-focused interviewer IM, one time in response to other-focused interviewer IM condition and two times in response to job/organization-focused interviewer IM, the ratio of preferred other-focused IM for this applicant would be 0.70 (i.e., 70%). We followed the same kind of procedure to calculate the ratio of preferred self-focused IM and the ratio of preferred job/organization-focused IM. To be consistent with study 1 and the adjacency pairs concept, we only included applicant IM used in the turn of speech immediately following the interviewer IM section (but not IM used when answering the interview question) in the analyses.Footnote 4

Applicant Positive Affect

Applicant positive affect was assessed after the interview with the five-item subscale of Thompson’s (2007) short-form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS, Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Participants were asked to indicate to what extent each of the items described how they felt right after the interview. An example item is “At the moment, I’m feeling active” with responses ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely, α = 0.70.

Interviewer Liking of Applicant

The interviewer indicated their liking towards the applicant after the interview using the three-item Liking scale by Wayne and Ferris (1990). We adapted the items to fit the context of an interview. An example item is “I like this applicant” with responses ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, α = 0.89.

Observer Liking of Applicant

In addition, because the interviewer was focused on following the interview script during the interview, which might have diminished their ability to assess their liking of the applicant, we trained two graduate I/O students—one of them with HR work experience, one of them with video analysis experience—to assess their liking of the applicant as independent observers. The two observers were blind to the conditions and hypotheses, and completed the same scale as the interviewer (α = 0.94) after watching the videotaped interviews. We used the same procedure as for the IM rater training: After a training session to develop a common understanding of the Liking scale and to rate liking independently from perceived performance (i.e., counteracting potential halo effects), 15 videos were assessed independently by each observer. The level of interrater reliability was acceptable, ICC2,1 = 0.64—especially when considering the subjective nature of rating liking—and comparable to previous studies with similar video rating procedures (Swider, Barrick, & Harris, 2016), so the rest of the 105 interviews were split between the two observers.

Interviewer Rating of Overall Interview Performance

The interviewer indicated their assessment of the applicants’ overall performance during the interview on five items by Higgins and Judge (2004). We adapted the items to fit the context of our interview scenario. An example item is “Overall, based on the interview, I would evaluate this applicant positively” with responses ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, α = 0.95.

Observer Rating of Overall Interview Performance

Similar to applicant liking (see above), the two observers completed the same scale as the interviewers to assess overall performance in the interview, α = 96. The level of interrater reliability based on 15 videos was acceptable, ICC2,1 = 0.79, so the rest of the 105 interviews were split between the two observers.

BARS Interview Performance

To also include a more standardized, objective performance measure, BARS (behaviorally anchored ratings scales) interview performance was assessed by mechanically combining (i.e., averaging) ratings of the responses to the eight structured interview questions. All responses were rated on 5-point BARS (1 = poor to 5 = superior) covering the two dimensions of persistence and organizing behaviors (used and validated in past research, see Ingold et al., 2015). BARS performance was assessed by one of two raters. Importantly, the two raters were the same as for the IM ratings, but the videos of different applicants were assigned in such a way that raters assessed the performance of those applicants for which they did not code IM (i.e., every rater assessed each interview just once) to avoid any confounds between the ratings. In addition, raters were blind to the conditions and were only shown the video sections that they needed to assess interview performance (i.e., the question and answer portion of the interview only, not the interviewer IM sequences). Like with IM, the two raters participated in a frame-of-reference training (Bernardin & Buckley, 1981) that focused specifically on rating interview performance and took place 2 months after the frame-of-reference training for IM coding. After the training, videotapes of 15 interviews were rated independently by the two raters. Interrater reliability was acceptable (ICC2,1 = 0.60); thus, the rest of the 105 interviews were split between the two raters.

Control Variables

Control variables were included based on theoretical justifications (Becker, 2005). Past research has shown that applicants’ use of IM can be influenced by prior work experience because it can facilitate highlighting one’s qualifications (Bourdage et al., 2018). In addition, applicants with more interview experience are more familiar with the interview setting, which can increase IM use and interview performance and influence applicants’ reaction to the interview (Harris & Fink, 1987; Marcus, 2009; Schreurs et al., 2005). We therefore asked the number of years of work experience the participant had. In addition, we measured applicants’ interview experience with an item developed by Harris and Fink (1987) that read “How many prior interviews have you had in your life?” Following recommendations by Becker et al. (2016), analyses were run without and with the control variables to contrast the findings.

Results

Description of IM Use

Table 4 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables. In addition, when looking at all of applicants’ 1680 turns of speech in the whole study (120 applicants with 14 turns each), only 39 turns (2.32%) did not contain any IM.Footnote 5 Compared to study 1, there were fewer instances of turns without any IM because of the standardized interview protocol that counteracted conversational habits/tics and because we only examined applicants’ turns as interviewers’ turns were scripted. Table 5 shows descriptive statistics and mean differences for the frequencies of applicant IM in each interviewer IM condition (self-focused vs. other-focused vs. job/organization focused IM). In Table 5, we report different categories of IM use: (1) applicants’ IM use in response to the interviewer’s IM (but before the interviewer asked the interview questions), (2) applicants’ IM use in response to the interview questions, and (3) applicants’ overall IM use in each condition. Within each category, we compare applicants’ use of the three types of IM across the three interviewer IM conditions. In addition, there was a fourth condition (i.e., baseline condition) that differed from the three interviewer IM conditions in that interviewers did not use any IM and directly asked the interview question (i.e., the condition consisted only of interview questions, see Table 10 in the Appendix). In this baseline condition, applicants responded with some self-focused IM (M = 2.27, SD = 1.09), but almost no other-focused IM (M = 0.01, SD = 0.09) or job/organization-focused IM (M = 0.01, SD = 0.09). More information on the baseline condition and descriptive statistics on all conditions can be found in Table 12 in the Appendix.

IM Patterns

To test hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a, we ran ANOVAs for each type of applicant IM separately and examined variations in the amount of the respective type of IM used in response to interviewer IM across interviewer IM conditions (see the upper part of Table 5). In other words, interviewer IM served as the independent variable (within-subjects variable) and the amount of the respective type of IM used by applicants as the dependent variable. Hypothesis 1a assumed that applicants use more self-focused IM when the interviewer uses other-focused (compared to when the interviewer uses self-focused or job/organization-focused IM). A repeated measures ANOVA with interviewer IM as a three-level (i.e., other-focused, self-focused, and job/organization-focused interviewer IM) within-subjects variable and amount of applicant self-focused IM as dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of interviewer IM on applicant self-focused IM, F (1.89, 224.92) = 49.10, p < 0.001, ε = 0.945, η2 = 0.292.Footnote 6 Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction confirmed that other-focused interviewer IM led to more applicant self-focused IM than did the other IM types, providing additional support for hypothesis 1a.

Hypothesis 2a assumed that applicants use more other-focused IM when the interviewer uses self-focused IM (compared to when the interviewer uses other-focused or job/organization-focused IM). A repeated measures ANOVA with amount of applicant other-focused IM as the dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of interviewer IM on applicant other-focused IM, F (1.76, 209.67) = 226.78, p < 0.001, ε = 0.881, η2 = 0.656. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction confirmed that self-focused interviewer IM led to more applicant other-focused IM than did the other IM types, providing additional support for hypothesis 2a.

Hypothesis 3a assumed that applicants use more job/organization-focused IM when the interviewer uses job/organization-focused IM (compared to when the interviewer uses other-focused IM or self-focused IM). A repeated measures ANOVA with amount of applicant job/organization-focused IM as the dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of interviewer IM on applicant job/organization-focused IM, F (1.66, 197.73) = 115.04, p < 0.001, ε = 0.831, η2 = 0.492. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction showed that job/organization-focused interviewer IM led to more applicant job/organization-focused IM than did the other IM types, providing additional support for hypothesis 3a.Footnote 7

In this study, interviews were designed so that we could differentiate applicant IM used in response to interviewer IM and in response to interview questions. As additional analyses, when only taking applicant IM in response to interview questions into account (see the middle part of Table 5), we did not find any significant influence of interviewer IM on self-focused applicant IM, F (1.92, 228.52) = 0.84, p = 0.428, ε = 0.960, η2 = 0.007, other-focused applicant IM, F (1.27, 151.02) = 1.17, p = 0.295, ε = 0.635, η2 = 0.010, or job/organization-focused applicant IM, F (1.45, 171.99) = 0.08, p = 0.861, ε = 0.723, η2 = 0.001. However, when taking all applicants’ responses throughout the interview into account (i.e., both responses to interviewer IM and to the interview questions—see the bottom part of Table 5), the pattern of results was the same as when only taking applicant responses to interviewer IM into account: interviewer IM had a significant impact on applicant self-focused IM, F (1.91, 226.89) = 50.56, p < 0.001, ε = 0.953, η2 = 0.300, applicant other-focused IM, F (1.76, 209.30) = 227.55, p < 0.001, ε = 0.879, η2 = 0.657, and applicant job/organization-focused IM, F (1.68, 199.27) = 113.75, p < 0.001, ε = 0.837, η2 = 0.489.Footnote 8

Impact on Interview Outcomes

Hypothesis 4 assumed that interviewees’ use of preferred forms of IM according to the adjacency pair concept would be related to (a) positive affect, (b) liking as evaluated by interviewers and observers, (c) overall interview performance as evaluated by interviewers and observers, and (d) BARS interview performance evaluated by independent raters beyond the influence of the amount of applicant IM used across the interview. For this purpose, we conducted hierarchical regression analyses with overall IM use and preferred patterns of IM adaptation entered as predictors (Table 6). Results of step 1 showed some positive effects of self-focused, other-focused, and job/organization-focused IM use on interview outcomes that are typical to the literature. For instance, applicants’ use of self-focused IM was positively related to overall interview performance ratings (β = 0.27, p = 0.003). However, we found no effects of preferred IM adaptation on any of the interview outcomes beyond the amount of IM used across the interview in step 2, except for BARS interview performance (β = 0.25, p = 0.010 for self-focused and β = 0.25, p = 0.010 for job/organizational-focused IM).

Discussion

Results of study 2 showed that applicants adapted their IM to interviewers’ IM in a pattern of preferred responses, thus confirming the findings obtained from study 1 (i.e., where applicants pursued the goal of obtaining a position in actual interviews and interviewers engaged in IM naturally) in a more controlled environment. Moreover, the experimental design ensured strong internal validity and allowed us to demonstrate clear causality in terms of within-applicant variation in IM during the interview in response to changes in interviewer IM. We found strong evidence for patterns of preferred IM adaptation. However, these patterns were neither related to outcomes reported by applicants (positive affect) nor to outcomes from interviewers and observers (liking and overall performance), with the exception of performance rated by independent raters (BARS performance). In addition, the amount of IM applicants used during the interview was a predictor of applicant positive affect and overall performance scores, a finding consistent with previous meta-analyses (e.g., Barrick et al., 2009).

General Discussion

Despite the broad consensus that both applicants (e.g., Bourdage et al., 2018) and interviewers (e.g., Wilhelmy et al., 2016) use IM behaviors in job interviews, research has been largely silent on whether and how applicants and interviewers adapt their use of IM to one another. This is surprising because the interview is defined as a setting in which applicants and interviewers personally interact (Levashina et al., 2014). Theoretical work suggests that IM behaviors are part of a dynamic and adaptive exchange of signals between the applicant and the interviewer (Bangerter et al., 2012). In addition, work on conversation analysis and adjacency pairs suggests that certain types of responses (and thus potentially adaptive IM behaviors) are more effective to create a positive impression (e.g., Holtgraves, 2010). Bringing together these two frameworks, we examined whether applicants and interviewers adapt their IM to one another in patterns of preferred responses and explored whether these patterns of preferred IM adaptation influence interview outcomes.

Results of both our analysis of transcripts from real interviews and our experimental study demonstrated that applicants and interviewers indeed adapt their IM behaviors to each other, for instance, by engaging more often in other-focused IM following the interaction partner’s use of self-focused IM. In our experimental study, we only found evidence for a positive influence of patterns of preferred IM adaptations on performance ratings derived through behaviorally anchored ratings scales, but not any other interview outcome (neither with correlations nor when incorporating control variables in regressions). However, we found that the amount of applicant IM during the whole interview was positively associated with several interview outcomes, particularly applicant positive affect and overall performance ratings.

Theoretical Contributions

Our research makes several theoretical contributions to the interview and IM literatures. First, it represents the first examination of the mutual interdependency of IM between two interaction partners—interviewers and applicants—and breaks new ground on interpersonal influence and IM research. In the IM literature, IM has mainly been studied as behaviors used to manage the impression that we project onto others to achieve desirable outcomes such as winning a negotiation, gaining better job performance ratings, selling a product, or gaining sympathy in a romantic date (Bolino & Turnley, 1999; Koslowsky & Pindek, 2011). By definition, IM in a dyadic setting is a behavior that is used to manage the impressions of one’s interaction partner (Koslowsky & Pindek, 2011). Our findings highlight the importance of not only studying IM use by one of the interacting individuals in isolation, but the interaction between the two individuals and how they adapt their IM to one another.

Second, and relatedly, this research provides an enhanced understanding of what influences IM in the employment interview. In the interview literature, there has been a tradition of research on antecedents of IM such as personality or interview format (e.g., Bourdage et al., 2018; Levashina & Campion, 2007; Peeters & Lievens, 2006). Our findings show that IM in a preceding turn of speech is an antecedent of IM in the next turn of speech. As such, the present research highlights that applicants and interviewers do not only engage in more or less IM because of who they are or which types of questions they ask or are asked, but also because of the IM behavior of their interaction partner.

Third, our research contributes to signaling theory (Bangerter et al., 2012) by providing evidence of how applicants and interviewers adapt the signals they send to the signals they receive from each other: Our findings show that the type of IM that is used serves as a signal that stimulates a preferred type of IM in the interaction partner. In addition, in our experiment, the patterns of preferred IM adaptations by applicants were only observed in their turn of speech immediately following the interview IM behavior, but not later in the interview. This suggests that IM as a signal evokes IM adaptation in the interaction partner instantly after the signal. In addition, our transcript study revealed that IM adaptation takes place in both directions—not only applicants adapting to interviewers but also interviewers adapting their IM to applicants’ IM. This represents initial evidence of the idea of adaptations within a specific job interview.

Finally, job interviews combine elements of adaptive verbal conversations with elements of pre-established so-called cognitive performing scripts. On the one hand, interviews deserve attention from a linguistic perspective to better understand micro-level patterns of adaptive communication between applicants and interviewers, such as patterns of preferred IM responses (Holtgraves, 2010). At the same time, there are clear and stable expectations towards applicants’ and interviewers’ roles and behaviors during the conversation—just like for scenes in a theater play (Kacmar & Hochwarter, 1995; Tullar, 1989a). According to Tullar (1989a), the applicant’s script encourages IM throughout the whole interview—mainly self-focused IM, but also other-focused and job/organization-focused IM. Following this applicant script (i.e., engaging in more IM in the interview, particularly self-focused IM) might therefore be more beneficial for applicants than adapting as one would in common conversations (i.e., patterns of preferred IM). Indeed, we found a predominance of patterns of preferred IM adaptations across both studies, but a lack of effects of IM adaptations for most interview outcomes in the experimental study. As Tullar (1989a) suggested, adaptive behavior can take place during the interview (e.g., patterns of preferred IM), but evaluations after the interview may be more strongly influenced by script-conforming behaviors (such as the amount of IM used in the interview).

Further evidence for the important role of IM use in interviewers’ and (more particularly) applicants’ scripts comes from the large number of unprompted IM behaviors found in the transcript study. Indeed, IM was often used when there was no IM in the preceding turn of speech. This could be because applicants and interviewers try to use IM whenever they can, as called for by their cognitive performing scripts. This is also consistent with the adjacency pair concept, which proposes that when there is no IM in a preceding turn of speech, applicants do not face any restriction, and are thus free to use any IM they want. Overall, our research shows that it seems important to differentiate a micro- (i.e., turn of speech by turn of speech) from a more macro-perspective (i.e., interview outcomes). And different concepts (e.g., adjacency pairs vs. cognitive performing script) are likely relevant to make predictions at different levels.

Practical Implications

Our findings also point to several practical implications. First, from an organization’s perspective, the lack of influence of preferred IM adaptation on most interview outcomes could in fact be seen as good news. IM use is sometimes perceived as biasing interview outcomes, and our findings suggest that IM adaptations tend to not add potential biases. Our additional analyses also suggest that organizations could increase interview structure to limit the opportunity to engage in patterns of IM as well. Our findings could be seen as disappointing for applicants because adapting one’s IM to the interviewer’s IM might not benefit their overall interview performance and being liked. This being said, it would be possible that not using preferred IM at all could be perceived as particularly rude by the interviewer, and lead to lower evaluations. However, failure to adapt one’s IM to the interviewer’s IM did not impede performance either. Using preferred IM responses was a predominant pattern in both of our studies, but overall, it seems rather advantageous for applicants to focus their effort on using higher amounts of the effective type such as self-focused IM.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the insights into fine-grained applicant-interviewer interactions during employment interviews, our findings need to be interpreted in light of the following limitations. The focus of this paper is on how the kind of IM used in a preceding turn of speech influences the kind of IM (study 1) and also the amount of IM (study 2) in the subsequent turn(s) of speech. However, we did not examine preferred IM responses in terms of the amount of IM as an antecedent of subsequent amount of IM, and the effects of discrepancy—and thus imbalance—between these amounts. Future research could, for example, expand the design of our experimental study by not only varying the kind of IM used by the interviewer, but also how much IM is used, and examine the influence on applicants’ adaptations. We also did not investigate temporal effects of IM patterns in our transcript study, given our limited data. Yet, we encourage future research to analyze larger datasets of longer interviews to examine if preferred IM patterns are more frequent early vs. late in the interview, and if engaging in preferred patterns earlier (vs. later) differently impacts interview outcomes. Larger datasets might also be useful to further examine the impact of interview structure (or specific structure components), as well as other interviewer characteristics (e.g., personality, communication skills) on the patterns of preferred vs. dispreferred IM between applicants and interviewers.

Furthermore, we only examined speech patterns that included IM in both turns and excluded turns of speech without IM (i.e., No IM) from our main analyses. We made this decision because such turns generally included conversational habits or interviewers’ questions that were unrelated to our research objectives (see additional analyses in the Open Science Repository). However, it is important to acknowledge that a substantial proportion of interactions in study 1 involved No IM patterns (as shown in Tables 1 and 2). Thus, including No IM in our study 1 analyses would have largely suppressed the focal effects in the chi-square analyses. Overall, it seems reasonable to expect that No IM responses could have an effect on interviewer-interviewee impressions and judgments. For example, a scenario where the interviewer says “Our organization is a great place to work” and the interviewee says nothing after (or just “Mhmm”) illustrates that a No IM response could be seen as inappropriate, and thus negatively influence interviewers’ judgments of interviewees. Thus, turns of speech without any IM seem practically relevant, and future research should examine under what conditions No IM might influence interviewers or applicants.

In addition, we focused on single-interviewer settings (using single interviewers in study 2 and treating multiple interviewers as one unit in study 1) to increase standardization and limit design complexity. In practice, however, interviews are often conducted by two or more interviewers. We would expect to find the same patterns of preferred IM adaptation in panel interviews, but that interviewers would also adapt their IM to one another, for example, by adding a compliment when the other interviewer compliments the applicant (to confirm their colleague’s statement). Such preferred responses within the team of interviewers could be strategically used to signal coherence and a positive organizational culture to applicants (Wilhelmy et al., 2016). Future studies should therefore also examine IM exchanges between interviewers.

In our second study, we used an experimental design and practice interviews in order to manipulate interviewer IM. Such a design allowed us to draw causal inferences about how applicants adapt their IM to interviewers’ IM. However, the experimental design could restrict external validity. To counteract this potential limitation, we pre-tested our IM manipulations with Human Resource professionals and used participants with work experience.

In both studies, we followed best-practice coding approaches from past IM research (e.g., Ellis et al., 2002), but the approach we applied does not fully capture the complexity of conversational exchanges such as IM adaptation. IM adaptation is a novel and theoretically complex topic, and we believe more work is required to fully understand the phenomenon and its implications. Future studies should seek to improve and expand on how conversations may be analyzed and coded beyond the coding scheme that we used. For instance, our use of the three types of IM (self-focused, other-focused, job/organization-focused) is consistent with the existing IM literature, but perhaps a more granular approach is required.

In addition, because of the coding approaches used in both studies, we were not able to ask interviewers and applicants about their intentions when presenting information, which could also have implications for the effects of IM adaptation. For example, a preferred response to a statement that is made with awareness and intent may have a more positive effect than a preferred response to a statement that is made more automatically. Although definitions of adaptation in the organizational literature (e.g., Chan, 2000; Dorsey et al., 2010) do not incorporate the strategic motivation of the actor, future research could more precisely examine if applicants and interviewers strategically decide to adapt their IM use to create a particular impression in terms of a motivated choice. For example, in simulated interview settings, applicants could be shown a recording of their interview (similar to Roulin, Bangerter, & Levashina, 2015) and asked to comment on their intent and specific motives to use IM and, more specifically, preferred IM responses.

Furthermore, the experimental study only focused on applicants’ adapting their IM to the interviewer’s IM, but as shown in study 1, interviewers also adapt their IM to the applicant’s IM. Yet, study 1 was based on a small sample of interviews, and included heterogeneous interviews, which is why the effects of interviewer IM adaptations on interview outcomes could not be examined. Future research should examine how interviewers’ patterns of IM adaptations influence relevant other outcomes, such as applicants’ intention to accept a job offer. In addition, experimental studies akin our study 2 could be designed with actors/confederates as applicants, manipulating applicant IM use (e.g., not using any IM), and examining interviewers’ IM responses or adaptations, as well the quality of interviewers’ judgments or decisions. Studies with larger samples could also allow for a more complex and even more precise examination of dynamic adaptations throughout the interview, for instance, by examining longer patterns of interactive responses beyond two or three turns of speech.

In addition, larger samples would also offer the opportunity to examine potential backfiring of extensive IM use. For example, an applicant or interviewer may dominate conversation for an extended period of time (Holtgraves, 2002). This can pose a threat to the turn-taking system because conversational turns represent a scarce resource, and therefore “an extended turn at talk represents a monopoly of this resource” and can be perceived as pretentious (Holtgraves, 2002, p.110). Such behaviors could lead to negative outcomes, unless both interaction partners mutually agree that an extended turn is appropriate (such as an applicant providing an answer to an interview question that clearly requires extensive elaboration). We encourage future studies to apply an even more fine-grained approach to identify instances of communication imbalance in the interview, how they are managed, and what effects they have.

Another aspect that should be considered in future research are cultural differences in IM adaptation and its effects. In the present study, we found evidence of patterns of preferred IM responses in two different cultural contexts—namely, in an English-speaking Canadian sample in study 1 and in a German-speaking Swiss sample in study 2—but more research is warranted to examine the cross-cultural validity of our findings. Future research could also build on past findings of cross-cultural differences in IM preferences to understand potential cross-cultural differences in IM adaptation. For example, Canadian interviewers (French-speaking in that sample) were found to be more inclined to hire self-promoting applicants whereas Swiss interviewers (also French-speaking) were found to be more inclined to hire modest applicants (Schmid Mast, Frauendorfer, & Popovic, 2011). In addition, it could be that patterns of IM adaptation and their effects are stronger in cultures that place more value on politeness than in cultures that place less value on it. For example, real interviews or experimental data could be compared across cultures, or interviewers’ and interviewees’ cultural background could be experimentally varied to examine effects of cultural similarities versus discrepancies.

Finally, in the experimental study, applicants engaging in more preferred IM were judged as providing stronger responses based on BARS performance ratings. As Swider et al. (2016) pointed out, “one possibility is that some applicants are simply more skilled at responding to all types of questions, regardless of the job relatedness of the question, thereby effectively signaling evidence of social competence” (p. 627). As preferred responses in conversations are an important aspect of communication and social skills (Holtgraves, 2010), this could explain the relationships between preferred IM adaptation and BARS performance scores. Thus, individual differences could account for applicants’ ability to both adapt to interviewer IM and provide convincing interview responses (e.g., personality and emotional intelligence). Future research should therefore examine such variables and their potential moderating role.

Conclusion

The tango is a dance in which two partners move in coordination, which means that both dancers and the way they interact matter. Similar to the tango, our study supports the notion that employment interviews need to be seen as a dynamic and interactive dialog in which applicants and interviewers adapt their behavior to their experience in the interview, including the other party’s IM behavior. At the same time, coordination is not the only necessary element to shine on the dancefloor or win a dance competition. Particularly, the interview deviates from the tango setting in that interviewers and applicants do not necessarily act in concert as each party is focused on their individual goals (filling the position vs. getting a job). Overall, our findings underscore the importance of a temporal approach to account for the interplay between interviewers and applicants in employment interviews. Fine-grained examinations of IM behavior and applicants’ and interviewers’ IM adaptations allow for a more precise understanding of how IM works, and we therefore call for more research into specific patterns of IM behaviors within interviews.

Notes

Please note that interviewers and applicants could record the interview without providing any descriptive information about themselves, which is why descriptive data on this sample is very limited (but available from the authors upon request).

While turns of speech with No IM represent an important portion of interviews, an analysis of their content revealed that they included mostly conversational tics/habits (e.g., “Mhmm”), processual statements, or follow-up questions by interviewers, which are unrelated to our research questions (see additional analyses available in the Open Science Repository). Such data were thus excluded from our main analyses.

Signaling theory also suggests ongoing spirals of adaptations and counter-adaptations of signals between interviewers and applicants (Bangerter et al., 2012). Longer exchanges can be broken down into multiple adjacency pairs (Holtgraves, 2002). For example, three turns of speech (A-B-C) can be split into two adjacency pairs (A-B and B-C). In other words, each turn of speech represents both a reaction to the previous turn and a prompt for the subsequent turn. Therefore, we also investigated whether preferred IM patterns would predominate among three consecutive turns of speech. Descriptive statistics for three-turn patterns are provided in Tables 7 and 8 in the Appendix, and results in Table 9 in the Appendix. In sum, results suggest that the hypothesized effects do generalize to three-turn patterns.

We also repeated the analyses using a ratio of preferred IM adaptations calculated based on applicant IM in the whole condition (i.e., not only in applicants’ responses to interviewer IM but also in their responses to interview questions) and the pattern of results remained the same.

Following the suggestion of a reviewer, we examined correlations between applicants’ amount of turns without any IM and the outcome variables. We found significant negative correlations with interviewer ratings of overall performance (r = − 0.27, p = 0.003), observer ratings of overall performance (r = − 0.19, p = 0.035), and BARS performance (r = − 0.27, p = 0.003).

Wherever Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated violation of the assumption of sphericity, we used the Huynh-Feldt correction to evaluate the F tests in this study (Girden, 1992).

As an alternative approach to testing Hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a, we conducted ANOVAs and pairwise comparisons for each condition separately and comparing the various types of applicant IM (type of applicant IM in response to interviewer IM as a within-subject factor). We found the same pattern of results (with just one exception: in the self-focused interviewer IM condition, the pairwise comparison between applicant other-focused IM (M = 3.21) and applicant self-focused IM (M = 2.58) was not significant).