Abstract

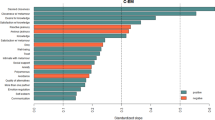

Marriage reduces risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) but marital stress increases risk, perhaps through cardiovascular reactivity (CVR). However, previous studies have lacked controls necessary to conclude definitively that negative marital interactions evoke heightened CVR. To test the specific effects of marital stress on CVR, 114 couples engaged in positive, neutral, or negative interactions in which speaking and task involvement were controlled. Compared to positive and neutral conditions, negative discussions evoked larger increases in systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output, and larger decreases in peripheral resistance and pre-ejection period—similarly for men and women. Hence, CVR could contribute to the effects of marital difficulties on CVD. Previous evidence of sex differences in this effect might reflect factors other than simple reactivity to negative interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

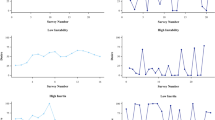

After participants completed questionnaires at the conclusion of the discussion task, they underwent a second 10-min baseline and participated in a second marital interaction task. Using the Couples Problem Inventory (Gottman et al. 1977), participants selected an issue that was currently contentious for both of them (e.g., money, children, in-laws). After a 3-min preparation period, participants took three 1-min turns speaking about the topic and three 1-min turns listening to their spouse in a structured interaction similar to the first task described above (speaking order was counterbalanced). They then continued to discuss the topic for an additional 4 min in an unstructured format. The physiological measures described above were recorded during these periods. Further, spouse ratings of friendliness and dominance, and self-reported anxiety and anger, were assessed as in the first task. This second task provided another opportunity to test sex differences in responses to marital conflict, again in a controlled task but one more closely resembling those used in prior research.

Statistical control of baseline physiological values and BMI did not alter the results reported in the remaining analyses of CVR.

Relative to baseline values, the second conflict discussion task evoked significant increases in self-reported anxiety and anger, SBP, DBP, CO, and HR, and significant decreases in TPR, PEP, and RSA. For the physiological variables, these changes were generally largest while participants spoke, smallest while they prepared for the task and listened to their spouse, and intermediate during the final unstructured discussion period. Men and women did not differ on changes in any of the physiological measures, all p-values >.20. However, women did report larger increases in anxiety (2.01 vs. 1.11, SE = .28, .35), F(1,111) = 7.66, p < .01, eta-squared = .065, and anger (1.74 vs. .87, SE = .36, .33), F(1,111) = 6.59, p < .02, eta-squared = .056) than did men. Further, women’s changes in anxiety were significantly correlated with their SBP reactivity during the task, r(113) = .32, p < .001, and their DBP reactivity, r(113) = .23, p < .02; their changes in anger were correlated with their DBP reactivity, r(113) = .23, p < .02. None of the associations between men’s reported change in affect and CVR during the second task approached significance. Hence, although the conflict discussion evoked expected increases in negative affect and CVR, as in the first task men and women did not differ in their cardiovascular responses. However, women did report larger increases in negative affect, and as in some prior research (Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001) these affective changes were related to CVR for women but not men.

Consistent with these findings, men and women did not differ in any cardiovascular response to the second conflict task (see footnote 3), even during a final unstructured portion of the task closely resembling commonly used marital interaction tasks. The fact that no sex differences emerged during that unstructured portion of the task is inconsistent with several prior studies (Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001), but could reflect the fact that the preceding structured portion of the discussion made the task engagement of men and women more similar than they otherwise would have been if only an unstructured task was used.

Additional findings support the validity of the negative interaction task used here as an analogue for more realistic marital conflict. First, participants’ ratings of their spouses’ behavior during this task were significantly correlated with their ratings of the spouse during the second, more traditional marital conflict discussion described in footnotes 1 and 3; correlations (n = 40) for wives’ and husbands’ ratings of spouse friendliness and dominance ranged from .67 to .84, all p-values < .001. Further, as was the case for these ratings during the second and more traditional task, ratings of friendliness and dominance during the negative task were significantly correlated with participant’s reports of general levels of marital conflict as assess by the Quality of Relationship Inventory-Conflict Scale (Pierce et al. 1991); correlations (n = 40) ranged from .42 (absolute value) to .78, all p-values <.01. Heart rate and blood pressure responses to the negative discussion and traditional conflict tasks were significantly correlated; correlations (n = 40) ranged from a low of .29, p < .07 (husbands’ DBP) to a maximum value of .75, p < .001 (husbands’ HR); wives’ values were r(40) = .46 to .67. When comparing mean responses to these two tasks directly, compared to the traditional conflict task described in footnote 1 the negative discussion task evoked: similar increases in anger, F(1,39) = .18; larger increases in anxiety, F(1,39) = 6.05, p < .02; equal ratings of the spouses’ dominance, F(1,39) = 1.93, p > .17; ratings of spouse as more hostile, F(1,39) = 5.57, p < .03; equal DBP reactivity, F(1,39) = .04; greater SBP response, F(1,39) = 18.39, p < .001; and greater HR reactivity, F(1,39) = 39.72, p < .001. Hence, although the smaller responses to the traditional task could reflect the fact that it was always presented second and hence participants may have habituated somewhat, it is clear that the negative task was not less stressful than the more commonly used and potentially more realistic conflict discussion. Further, perceptions of the spouse’s level of warmth and dominance during the negative task were closely correlated with the couples’ reports of general conflict in the marriage. Together, these findings provide additional evidence beyond the manipulation checks of the validity of the negative task as a manipulation of marital conflict.

References

Allen, M. T., Stoney, C. M., Owens, J. F., & Matthews, K. A. (1993). Hemodynamic adjustments to laboratory stress: The influence of gender and personality. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 505–517.

Baker, B., Paquette, M., Szalai, J. P., Driver, H., Perger, T., Helmers, K., O’Kelly, B., & Tobe, S. (2000). The influence of marital adjustment on 3-year left ventricular mass and ambulatory blood pressure in mild hypertension. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160, 3453–3458.

Berkman, L. F. (1995). The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57, 245–254.

Bernhardsen, C. S. (1975). Type I error rates when multiple comparisons follow a significant F test in AVOVA. Biometrics, 31, 229–232.

Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T., & Quigley, K. S. (1995). The metrics of cardiac chronotropism: Biometric perspectives. Psychophysiology, 31, 44–61.

Berntson, C. G., Quigley, K. S., Jang, J., & Boysen, S. T. (1990). An approach to artifact identification: Application to heart period data. Psychophysiology, 27, 586–598.

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2007). Emotion and motivation. In: J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed., pp. 581–607). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Broadwell, S. D., & Light, K. C. (1999). Family support and cardiovascular responses in married couples during conflict and other interactions. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 6, 40–63.

Cacioppo, J. T., Uchino, B. N., & Bernston, G. G. (1994). Individual differences in the autonomic origins of heart rate reactivity: The psychometrics of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and pre-ejection period. Psychophysiology, 31, 412–419.

Christensen, A., & Heavey, C. L. (1990). Gender and social structure in the demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 73–81.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

Cohen, S., Kaplan, J. R., & Manuck, S. B. (1994). Social support and coronary heart disease: Underlying psychological and biological mechanisms. In: S. A. Shumaker & S. M. Czajkowski (Eds.), Social support and cardiovascular disease (pp. 195–122). New York: Plenum.

Coyne, J. C., Rohrbaugh, M. J., Shoham, V., Sonnega, J. S., Nicklas, J. M., & Cranford, J. A. (2001). Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. American Journal of Cardiology, 88, 526–529.

Cross, S. E., & Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 5–37.

Davis, M. C., Matthews, K. A., & Twamley, E. W. (1999). Is life more difficult on Mars or Venus? A meta-analytic review of sex differences in major and minor life events. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 83–97.

Denton, W. H., Burleson, B. R., Hobbs, B. V., Von Stein, M., & Rodriguez, C. P. (2001). Cardiovascular reactivity and initiate/avoid patterns of marital communication: A test of Gottman’s psychophysiologic model of marital interaction. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 401–421.

Ewart, C. K., Taylor, C. B., Kraemer, H. C., & Agras, W. S. (1984). Reducing blood pressure reactivity during interpersonal conflict: Effects of marital communication training. Behavior Therapy, 15, 473–484.

Ewart, C. K., Taylor, C. B., Kraemer, H. C., & Agras, W. S. (1991). High blood pressure and marital discord: Not being nasty matters more than being nice. Health Psychology, 10, 155–163.

Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (1999). Conflict in marriage: Implications for working with couples. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 47–77.

Fincham, F. D., & Linfield, K. J. (1997). A new look at marital quality: Can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 489–502.

Gallo, L. C., Smith, T. W., & Kircher, J. C. (2000). Cardiovascular and electrodermal responses to support and provocation: Interpersonal methods in the study of psychophysiologic reactivity. Psychophysiology, 37, 289–301.

Gallo, L. C., Troxel, W. M., Kuller, L. H., Sutton-Tyrrell, K., Edmundowicz, D., & Matthews, K. A. (2003). Marital status, marital quality, and atherosclerotic burden in postmenopausal women. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 952–962.

Girdler, S. S., Turner, J. R., Sherwood, A., & Light, K. C. (1990). Gender differences in blood pressure control during a variety of behavioral stressors. Psychosomatic Medicine, 52, 571–591.

Gottman, J. M., Markman, H., & Notarious, C. (1977). The topography of marital conflict: A sequential analysis of verbal and nonverbal behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 39, 461–477.

Helgeson, V. S. (1994). Relation of agency and communion to well-being: Evidence and potential explanations. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 412–428.

Jennings, J. R., Kamarck, T., Stewart, C., Eddy, M., & Johnson, P. (1992). Alternate cardiovascular baseline assessment techniques: Vanilla or resting baseline. Psychophysiology, 24, 474–475.

Kamarck, T. W., Peterman, A. H., & Raynor, D. A. (1998). The effects of social environment on stress-related cardiovascular activation: Current findings, prospects, and implications. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 20, 247–256.

Kenny, D. A. (1995). Design and analysis issues in dyadic research. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 11, 164–184.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Glaser, R., Cacioppo, J. T., MacCallum, R. C., Snydersmith, M., Kim, C., & Malarkey, W. B. (1997). Marital conflict in older adults: Endocrinological and immunological correlates. Psychosomatic Medicine, 59, 339–349.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Malarkey, W. B., Chee, M., Newton, T., Cacioppo, J. T., Mao, H.-Y., & Glaser, R. (1993). Negative behavior during marital conflict is associated with immunological down-regulation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 395–409.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Newton, T. L. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503.

Kiesler, D. J. (1996). Contemporary interpersonal theory and research: Personality, psychopathology and psychotherapy. New York: Wiley.

Kiesler, D. J., Schmidt, J. A., & Wagner, C. C. (1997). A circumplex inventory of impact messages: An operational bridge between emotion and interpersonal behavior. In R. Plutchik & H. R. Conte (Eds.), Circumplex models of personality and emotions (pp. 221–224). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kop, W. J. (1999). Chronic and acute psychological risk factors for clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61, 476–487.

Lawler, K. A., Wilcox, Z. C., & Anderson, S. F. (1995). Gender differences in patterns of dynamic cardiovascular regulation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57, 357–365.

Leopre, S. J. (1998). Problems and prospects for the social support—reactivity hypothesis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 20, 257–269.

Litvack, D. A., Oberlander, T. F., Carney, L. H., & Saul, J. P. (1995). Time and frequency domain methods for heart rate variability analysis: A methodological comparison. Psychophysiology, 32, 492–504.

Llabre, M. M., Spitzer, S. B., Saab, P. G., Ironson, G. H., & Schneiderman, N. (1991). The reliability and specificity of delta versus residualized change as measures of cardiovascular reactivity to behavioral challenges. Psychophysiology, 28, 701–711.

Margolin, G., Talovic, S., & Weinstein, C. D. (1983). Areas of change questionnaire: A practical approach to marital assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 920–931.

Matthews, K. A., & Gump, B. B. (2002). Chronic work stress and marital dissolution increase risk of post-trial mortality in men from the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162, 309–315.

Mattson, R. E., Paldino, D., & Johnson, M. D. (2007). The increased construct validity and clinical utility of assessing relationship quality using separate positive and negative dimensions. Psychological Assessment, 19, 146–151.

Mayne, T. J., O’Leary, A., McCrady, B., Contrada, R., & Labouvie, E. (1997). The differential effects of acute marital distress on emotional, physiological and immune functions in maritally distressed men and women. Psychology and Health, 12, 277–288.

Nealey, J. B., Smith, T. W., & Uchino, B. N. (2002). Cardiovascular responses to agentic and communal stressors in young women. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 395–418.

Neuvo, Y., Cheng-Yu, D., & Mitra, S. (1984). Interpolated finite impulse response filters. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 32, 563–570.

Newton, T. L., & Sanford, J. M. (2003). Conflict structure moderates associations between cardiovascular reactivity and negative marital interaction. Health Psychology, 22, 270–278.

Orth-Gomer, K., Wamala, S. P., Horsten, M., Schenck-Gustafsson, K., Schneiderman, N., & Mittleman, M. A. (2000). Marital stress worsens prognosis in women with coronary heart disease: The Stockholm female coronary risk study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284, 3008–3014.

Pierce, G. R., Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (1991). General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 1028–1039.

Robles, T. F., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2003). The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiology and Behavior, 79, 409–416.

Schmidt, J. A., Wagner, C. C., & Kiesler, D. J. (1999). Psychometric and circumplex properties of the octant scale impact message inventory (IMI-C): A structural evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 325–334.

Sherwood, A., Allen, M. T., Fahrenberg, J., Kelsey, R. M., Lovallo, W. R., & van Doornen, L. J. P. (1990). Methodological guidelines for impedance cardiography. Psychophysiology, 27, 1–23.

Sherwood, A., Dolan, C. A., & Light, K. C. (1990). Hemodynamics of blood pressure responses during active and passive coping. Psychophysiology, 27, 656–668.

Siegman, A. W., Dembroski, T. M., & Crump, D. (1992). Speech rate, loudness, and cardiovascular reactivity. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15, 519–523.

Smith, T. W., Gallo, L. C., Goble, L., Ngu, L. Q., & Stark, K. A. (1998). Agency, communion, and cardiovascular reactivity during marital interaction. Health Psychology, 17, 537–545.

Smith, T. W., Gallo, L. C., & Ruiz, J. M. (2003). Toward a social psychophysiology of cardiovascular reactivity: Interpersonal concepts and methods in the study of stress, coronary disease. In J. Suls & K. Wallston (Eds.), Social psychological foundations of health and illness (pp. 335–366). UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Smith, T. W., Limon, J. P., Gallo, L. C., & Ngu, L. Q. (1996). Interpersonal control and cardiovascular reactivity: Goals, behavioral expression, and the moderating effects of sex. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1012–1024.

Smith, T. W., Nealey, J. B., Kircher, J. C., & Limon, J. P. (1997). Social determinants of cardiovascular reactivity: Effects of incentive to exert influence and evaluative threat. Psychophysiology, 34, 65–73.

Smith, T. W., Ruiz, J., & Uchino, B. N. (2000). Vigilance, active coping, and cardiovascular reactivity during social interaction in young men. Health Psychology, 19, 382–392.

Smith, T. W., Ruiz, J. M., & Uchino, B. N. (2004). Mental activation of supportive ties, hostility, and cardiovascular reactivity to laboratory stress in young men and women. Health Psychology, 23, 476–485.

Snyder, D. K., Heyman, R. E., & Haynes, S. N. (2005). Evidence-based approaches to assessing couple distress. Psychological Assessment, 17, 288–311.

Spielberger, C. D. (1980). Preliminary manual for the State-Trait Personality Inventory. Tampa: University of South Florida, Human Resources Institute.

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not flight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107, 411–429.

Tomaka, J., Blascovich, J., Kelsey, R. M., & Leitten, C. L. (1993). Subjective, physiological, and behavioral effects of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 248–260.

Traupman, E., Smith, T. W., Uchino, B. N., Berg, C. A., Trobst, K. K., & Costa, P. T. (2007). Interpersonal circumplex descriptions of psychosocial risk factors for physical disease: Application to the domains of hostility, neuroticism, and marital adjustment (under review).

Treiber, F. A., Kamarck, T., Schneiferman, N., Sheffield, D., Kapuku, G., & Taylor, T. (2003). Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 46–62.

Uchino, B. N. (2004). Social support and physical health outcomes: Understanding the health consequences of our relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Uchino, B. N., Cacioppo, J. T., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (1996). The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 488–531.

Wiggins, J. (1996). An informal history of the interpersonal circumplex. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 361–382.

Wright, R. A., & Kirby, L. D. (2001). Effort determination of cardiovascular response: An integrative analysis with applications in social psychology. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 255–307). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nealey-Moore, J.B., Smith, T.W., Uchino, B.N. et al. Cardiovascular Reactivity During Positive and Negative Marital Interactions. J Behav Med 30, 505–519 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9124-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9124-5