Abstract

Based on a sample of 46 Portuguese schoolbooks, this study aims to understand how factory-farmed animals are presented in such books across the themes of food and health, the environment and sustainability, and animal welfare. It examines whether schoolbooks address the importance of reducing the consumption of animal-based products for a healthy diet, whether plant-based diets are recognized as healthy, whether animal welfare and agency are considered, and whether the livestock sector is indicated as a major factor in environmental degradation. The findings show that schoolbooks present animals as essential for economic activities and human nutrition. Recommendations on reducing the consumption of animal-based products in consideration of the environment, sustainability and human health are very rare. Animal production is presented as benign, and the agency and welfare of factory-farmed animals are simply not addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The current impacts of factory farming are quite concerning and deserve greater attention from educational actors, students and consumers, as the livestock sector is partly responsible for environmental degradation (Jamieson, 1998; Young, 2010; FAO, 2013; Gerber et al., 2013) and global warming (IPCC, 2019). At a time when hunger affects one billion people across the globe (Grainger, 2016), animal farming is excessively demanding in its use of natural resources (FAO, 2006; Young, 2010). A substantial reduction in meat consumption can directly benefit human health, as it can decrease the risks of obesity, type 2 diabetes (Liu et al., 2018), cancers (WCRF, 2007; Oostindjeret et al., 2014) and cardiovascular diseases (Zhong et al., 2020).

As an inherent condition of laissez-faire liberalism, modern factory farming operates under many of the same parameters as other production industries (Harfeld, 2011). That is, animal agriculture requires the intensification of housing systems to obtain the desired output level (Harfeld, 2011) as quickly as possible. In factory farms, animals remain tethered or confined (European Convention for the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes, 2009), in many cases without access to daylight, and often suffer from castration or (tail and horn) mutilation without anaesthetics (Eur-Lex, 2008). Females are forced to reproduce and, after gestation, are separated from their offspring, resulting in increased cortisol levels and vocalizations (Hudson & Mullord, 1977). Due to their harsh living conditions, livestock animals show stereotypical signs of distress (Harfeld, 2011), and are afflicted by several diseases (Brooks-Pollock et al., 2015). Other clear signs of physical and emotional stress are seen among animals in slaughterhouses. In these concealed places, and far from the consumers’ sight and hearing, sentient beings are continuously treated as raw material (Pachirat, 2011). Considering these ethical dilemmas, environmental pedagogy in schools can play an important role in developing attitudes and skills among students to envisage a prosperous future for all life on the planet.

This article aims to understand how a sample of primary school textbooks present animal-related issues in relation to (a) food and health, (b) animal welfare, and (c) the environment and sustainability. Specifically, I investigate whether schoolbooks address how reducing the consumption of animal-based products and eating more plant-based foods can ensuring a healthy diet and improve animal welfare; what the correlation is between meat and fish consumption with environmental impacts; and whether plant-based diets are viable and sustainable. The methods applied in this study involved counting and analysing text excerpts and images (subject mentions) in 46 Portuguese schoolbooks falling under the following main themes: (a) animals, food and health, (b) animal welfare, and (c) the environment and sustainability (see the subthemes in Table 1). The results section reveals that animals used for food are evidently classified as consumable and essential for human needs, while plant-based diets are marginalized. Regarding animal welfare and agency, schoolbooks favour the moral protection of pets but do not advocate similar principles for factory-farmed animals. Animal slaughter and suffering are not mentioned, and the species involved in factory farming are mainly represented as being free from confinement and with apparently well-being. On matters related to the environment and sustainability, schoolbooks downplay meat production and industrial fishing as threats to the environment and biodiversity. The analysed sample reflects an environmental education model that does not tend to address the current impacts of factory farming and industrial fishing along its main dimensions: animal welfare and agency, human health, the environment, and sustainability. Thus, the model does not stress the importance of reducing animal-based product consumption or highlight the importance of adopting plant-based diets for tackling climate change and environmental degradation. In the discussion section, I challenge the invisibility of the precarious living conditions of factory-farmed animals and the omission of the environmental impacts of factory farming. In the last section, I suggest possible courses of action for an eco-centric and sustainable educational model and point to new directions for further research.

Animals Used for Consumption in Environmental Education: Literature Review

The current national environmental programmes are an extension of Portugal’s framework for environmental education (Câmara et al., n.d.). This public document addresses crucial topics such as soil degradation and deforestation, sustainable agriculture, anthropogenic greenhouse gases, fossil fuels and alternative energy sources, the importance of water for human activities, and the adoption of environmentally responsible behaviours (Câmara et al., n.d.). A closer examination reveals that this institutional document lacks guidelines regarding the negative impacts of factory farming on animals, human health, the environment and natural resource management. In conjunction, animals used for food are limited to an anthropocentric framing, and they are not indicated as species that students should respect and value.

Anthropocentric thinking is a hegemonic belief system, transversal to major institutions of socialization (i.e., the state, media, private sector, educational system, and family), where humans are understood as separate from and superior to all other living beings (Brennan & Norva, 2021; Lloro-Bidart, 2015; Lupinacci & Happel-Parkins, 2016). However, it is not just consumer culture that raises serious concerns for environmental educators committed to reversing the destructive human-animal relations of globalizing societies (Timmerman & Ostertag, 2011). Reflecting human-supremacist cultural conventions, environmental education programmes depict animals used for food and all life on Earth from an instrumentalist perspective, that is, as resources to be exploited (Pedersen, 2010; Dinker et al., 2016; Lloro-Bidart & Banschbach, 2019; Oakley, 2019; Ross, 2020). By neutralizing the oppression of animals (Twine, 2010; Cole & Stewart 2015) while promoting the absence of moral guidelines (Dolby, 2019; Spannring, 2017), education in schools enables students’ emotional detachment, facilitating their acceptance of the idea that certain species are killable (Pedersen, 2010) and replaceable commodities (Jamieson, 1998). What is taught in schools about animal farming is not generally associated with sustainability and the environment (Rawles, 2017; Twine, 2010). Additionally, the viability of plant-based diets is disregarded (Arken, 1989; Cole & Stewart, 2015).

Although scarce, there is relevant research based on critical animal studies that explores how human-animal relations are taught in environmental science classes (Twine, 2010; Pedersen, 2010; Dinker et al., 2016). However, there is a very small body of research that delves into the ways in which schoolbooks address the impacts of animal farming on human health, animals, the environment and sustainability. A pertinent study on these topics was published by Cole and Stewart (2015) and demonstrated the silence of British schoolbooks on animal suffering. In such books, animals are referred to as products, and plant-based diets are not indicated to be a healthy option. However, Cole & Stewart (2015) do not explore how the environment and sustainability are approached in textbooks.

Analysis from an Ecofeminist, Eco-centric, and Intersectional Framework

Reviewing the ways in which school materials represent the impacts of animal farming and consumption on (a) human health, (b) animals, and (c) the environment and sustainability necessitates the use of an intersectional theoretical framework that emphasizes the ethical relevance of each theme, as well as the pertinence of interconnecting the themes as interdependent variables. Environmental ethics theory is highly relevant for environmental education (Kronlid & Öhman, 2013), particularly for analysing theme b (environment and sustainability). Purposefully turning away from a human-centred exploratory approach that supports the instrumentalization of nature and other living beings (cf. Katz, 1991; Naess, 1973), this study is anchored in Leopold’s (1949) theoretical framework of “land ethics”, according to which humans should treat land and animals in an ethical manner. This framework is in line with Anderson’s (2005) and Taylor’s (1996) eco-centric theories, whose key points are conceiving of the environment as an aggregate system and considering the intrinsic value of animals. Regarding animal rights, Thompson (1994), Ross (2020), Brennan and Norva (2021) argue that animals used for food are unacceptably instrumentalized under a productivist view of nature. Jamieson (1998) points out that the livestock industry is one of the main causes of ecosystem degradation, injustice in food distribution and animal suffering. Finally, Waldau (2013) argues that animal protection and environmental conservation movements should work together to achieve shared goals.

Ecofeminist theory is very important for the ecological debate (Warren, 1987), and its analytical lenses are valuable for understanding human relations with nature and other animals. In Le Féminisme ou la Mort (1974), D’Eaubonne underlines the importance of understanding parallel forms of oppression of marginalized groups (women, people of colour, children, poor individuals, animals) through a common patriarchal structure (Brennan & Norva, 2021; Donovan, 1990; Kheel, 2008; Lloro-Bidart, 2019; Plumwood, 1993). Gaard (2017), Gaard and Murphy (1998) and Gaard and Gruen (1993) emphasize the role of capitalism in environmental degradation, with the subsequent reduction of all living beings to mere resources and assets to be instrumentalized (Plumwood, 1993), particularly in the animal-industrial complex (Noske, 1989). For Kheel (2008), ecofeminist theory ought to adopt a holistic approach to examining the damaging effects of food production on the environment and create awareness of dietary choices that do not require animals to be used for meals. Similarly, Adams (1990, 1995) and Gaard (2002) suggest that meat consumption is linked to the construction of manhood and the patriarchal oppression of women’s and animals’ bodies. Culturally reproduced in practices, perceptions, representations and even language, “meat” and other animal-based byproducts function as “absent referents” (Adams, 1990) that are central for humans’ emotional detachment towards animals used for food. Because the moral absence of animals extends to the classroom (Houde & Bullis, 1999), ecofeminist pedagogies can be applied to interrogate hegemonic dominant discourses and practices in food and in environmental educational programmes (Brennan & Norva, 2021; Houde & Bullis, 1999; Lloro-Bidart, 2019).

By enabling a straightforward understanding of human-animal relations and representations in the educational domain, theme (b) (animal welfare) in this study is also grounded in the analytical lens of critical animal studies—an ethically committed intersectional approach that actively works against all forms of oppression, envisioning the liberation of humans, animals and the planet as a common struggle. Taylor and Twine (2014), Lloro-Bidart (2015), Lupinacci and Happel-Parkins (2016) reference the anthropocentric status quo in human-animal relations that is reproduced in current mainstream practices and institutionalized social norms. In particular, in the educational realm, Pedersen (2010), Cole and Stewart (2015), Dinker (2016), Lloro-Bidart, (2019), and Oakley (2019) have used the lens of critical animal studies to ascertain that educational programmes convey cultural conventions whereby the exploitation, commodification and consumption of animals are neutralized and dissociated from their environmental impacts (Twine, 2010; Dinker et al.,2016).

The body of research mentioned above mostly explores how information about human-animal relations is taught in environmental classes. This research proposes to explore how a sample of 46 primary school textbooks (from grades 1 to 6) portray various impacts of animal production. It particularly seeks to grasp how animals used for human consumption are addressed across the following themes: (a) food and health (how often such animals are depicted as goods and protein sources; if there are recommendations to reduce meat consumption and adopt plant-based diets); (b) animal welfare and agency (if animals are represented in intensive or extensive farming; if they are subjects worthy of moral protection); and (c) the environment and sustainability (if the environmental impacts of the livestock industry are made visible).

These themes/categories (a, b, c) were selected because they represent key challenges that our planet is currently facing due to the production and consumption of animals. Furthermore, these topics are related to the ways in which humans conceptualize and interrelate with other species used for food. In addition to having horrendous impacts on animals (Brooks-Pollock et al., 2015; Pachirat, 2011), factory farming and animal-based product consumption have considerable consequences for human health (Liu et al., 2018; WCRF, 2007; Zhong et al., 2020), the environment (Young, 2010; FAO, 2013; Gerber et al., 2013; IPCC, 2019), food security and sustainability (food, water, soil) (FAO, 2006; Young, 2010; Grainger, 2016).

In globalized societies, environmental education can play a decisive role in enlightening students about sustainable and healthy eating practices. Encouraging them not to take part in animal suffering is a primary course of action for tackling global warming and the current environmental crisis. By identifying the weaknesses in how themes (a, b, c) are depicted in primary school textbooks, this article intends to improve current environmental educational programmes.

Methods: Data Collection and study Design

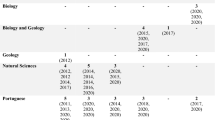

To answer the primary research question—how are the impacts of animal production depicted in schoolbooks with regard to the themes of (a) animal welfare, (b) human health and (c) environmental effects?—the following procedures were followed. (i) I gathered and identified published primary school textbooks (see the index) that contain the checklist themes; (ii) I assessed and collected data (images and texts); (iii) I presented the findings by counting the subject mentions (778 total) (see Table 1); and (iv) I interpreted the findings with the support of a theoretical framework (see the section From an eco-centric and intersectional analytical framework).

Each subject mention corresponds to either an image or an idea in a text, not both. Counting each subject mentions made it possible to assess the prevalence of each subtheme. The study data were found most frequently in schoolbooks for environmental studies, the natural sciences and Portuguese (see the index). Within the three main themes (a) animals, food and health, (b) animal welfare, and (c) the environment and sustainability, the following subthemes were observed:

-

(a)

In the category of animals, food and health (Fig. 2), the following information was extracted: the frequency with which the schoolbooks classify animals as consumables (e.g., meat, fish); whether the books also label plant-based foods as protein sources; whether the book recommends reducing the consumption of animal-based products, particularly red meat; and whether the book considers plant-based diets to be feasible.

-

(b)

In the category of animal welfare (Fig. 5), the following information was extracted: whether the schoolbooks depict animals in representative locations (intensive farming) or nonrepresentative locations (extensive farming); whether the suffering of animals is made visible in the books; and whether, like pets, factory-farmed animals are portrayed as subjects worthy of moral protection in the books.

-

(c)

In the category of the environment and sustainability (Fig. 7), the following information was extracted: whether the schoolbooks make visible the environmental impacts of the livestock industry and its management of natural resources (soil, water, cereals); the books’ recommendations for students to alter individual behaviours vis-à-vis environmental mitigation; whether these recommendations involve reducing the consumption of animal-based products; and whether plant-based diets are considered viable in the books.

Limitations of the Study

The sample includes 46 primary school textbooks published between 2012 and 2020. Five books were obtained for grade 1, eight books for grade 2, five books for grade 3, five books for grade 4, twelve books for grade 5, and nine books for grade 6. The most common date of publication among the sample was 2020 (11 books), with an average distribution of 4 to 5 publications for each of the previous years (except for 2018) since 2011. The sample used for analysis reflects a wide range of content, and the specificities within each theme identified are in line with the research objectives.

Results

Within the theme animals, food and health (Fig. 2), the classification of animals as food, resources and tradable goods has the highest number of subject mentions (352), with the greatest incidence in 4th-grade schoolbooks (Table 1). Animals are framed as “national economic activities” as “sources of wealth”Footnote 1, “resources” or “exploitable goods”, and “raw material” from which meat, leather, wool, milk and eggs are “extracted”Footnote 2Footnote 3. Animals are presented as being “possible to catch in aquatic environments” or “reared in appropriate places”, such as cowsheds and poultry farmsFootnote 4. They are also defined as saleable goods in meat markets or as meat packages in supermarketsFootnote 5. Some books encourage students to understand that animals “supply” their meat, milk, leather and eggsFootnote 6. Animals also frequently appear in food charts and pictures of everyday life, i.e., as steak, stereotyped meat or fish, eggs, roast chicken, ham, burgers, sausages, sardines, mackerel, horse mackerel, octopus, tuna, seafood, lamprey, squid, or shadFootnote 7. Portuguese gastronomy is presented as rich and delightful in images of everyday life, festivities, or activities where animals (of the land and sea) are converted into foodFootnote 8.

The sample (Table 1) includes 111 mentions that the intake of protein and calcium (“reconstructive” sources) depends on animal-based products; the importance of the whole family adopting a Mediterranean diet, which includes animal-based productsFootnote 9, is emphasized. Poultry, fish, red meat, eggs and dairy productsFootnote 10 are frequently mentioned as “reconstructive foods” that ensure the “health and safety of muscles”Footnote 11. Legumes appear in food chartsFootnote 12, but the texts do not mention them as viable sources of protein (Fig. 1).

Thirteen subject mentions encouraging fish as a healthy food are found (Table 1)Footnote 13. Plant-based reconstructive sources of protein are not directly advertised as being viable or healthier than other sources of protein. Only one directly statement that calcium can be found in a wide variety of foods, including plant-based options such as “beans, cabbage, broccoli and tofu”Footnote 14, is found (Table 1).

Eight references of the harmful effects of animal-based products on human health are found (Table 1), concentrated in sixth-grade schoolbooks. For instance, one text mentions that obesity is associated with the consumption of fast-food hamburgers and advises students to reduce their consumption of meat and dairy productsFootnote 15 (Fig. 2).

Within the category of animal welfare (Fig. 5), schoolbooks—especially in grades 2 and 4—tend to represent animals in extensive farming activities and with apparently sufficient well-being (95 subject mentions, Table 1). In images, cows and calves appear in green pasturesFootnote 16, just like sheep and goatsFootnote 17 or even pigs, on family-type farmsFootnote 18 (Fig. 3). Only one schoolbook mentions that currently, a large amount of animal husbandry is carried out under intensive farming, which enables speedier growthFootnote 19. In the 3rd and 4th grades alone, 12 images (Table 1) of animals in intensive farming are found: chickens, cattle, goats, sheep, and pigsFootnote 20.

In “Estudo do Meio 3”. Although intensive factory farming is the most common form of farming in Portugal and other high income countries, animals tend to be depicted in extensive farming activities and with apparently sufficient well-being. The agency and suffering of farmed animals are not addressed

Not once is animal welfare or agency mentioned. In the text, animals classified as pets are much more valued than farmed animals (Table 1). There are exercises for students to distinguish between pets and wild animals or to choose their “favourite animal” (between a cat and a dog)Footnote 21.

There are 53 references to pets (Table 1) as cuddly, funny, sweet Footnote 22, and playfulFootnote 23; as needing to be cared for, protected and pettedFootnote 24; and as possibly bringing sadness after their deathFootnote 25 (Fig. 4). In only 4 subject mentions (Table 1) are animals intended for consumption described as being worthy of care and protection. Only one illustration with such a message, of a boy stroking a calf, is foundFootnote 26. Another subject mentionFootnote 27, alluding to a Christmas crib, gives animals (the cow and donkey) the responsibility of being affectionate towards baby Jesus (Figs. 5, 6).

The 1st- and 2nd-grade schoolbooks in this sample do not address topics related to the environment and sustainability (Fig. 7). Among the 74 subject mentions (Table 1), mineral extractionFootnote 28 and air pollution stand out, with a list of factors contributing to the latter: factories, chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) sprays, nuclear explosions, airplanes, city transportFootnote 29, forest fires and greenhouse gasesFootnote 30. Water pollution is also mentioned as a result of waste and discharge coming from paint, varnishes, detergents, oils, pesticides, fertilizers, oil, sewers, toxic waste, boat washing, nuclear wasteFootnote 31Footnote 32 and plasticFootnote 33. As for the factors leading to soil pollution, those mentioned are the rise in industrial and agricultural activities, urban waste, the decomposition of waste, pesticides used in agricultureFootnote 34, deforestationFootnote 35 and population growthFootnote 36. There are only 8 subject mentions (Table 1) of the negative impacts of animal farming on the environment, namely, as one of the reasons for deforestationFootnote 37 (Fig. 6), soil degradation and air pollutionFootnote 38, which can cause “noise, unpleasant smells and other inconveniences” for the populationFootnote 39.

There are 39 mentions of measures to mitigate environmental impacts (Table 1), with the greatest predominance in 4th-grade schoolbooks. Among these environmental protection measures, the importance of reducing waste is highlighted: “not throwing rubbish on the floor”Footnote 40, adopting the “3 Rs” and “5 Rs” policiesFootnote 41, saving water during different domestic activities (e.g., bathing, brushing teeth, and washing cars, clothes, and hands)Footnote 42 (Fig. 8), investing in alternative energy sources, using public transport and low-emission cars, and eating organic foodFootnote 43. Concerning the adoption of more environmentally friendly eating practices, the sample has only 1 mentionFootnote 44: encouraging a reduction in meat and fish consumption.

Discussion

This article analyses how a broad sample of primary school textbooks depict animal-related issues in relation to (a) food and health, (b) animal welfare, and (c) the environment and sustainability. The findings suggest that the current model of environmental education in Portugal underplays and disregards the various impacts of animal production, ultimately helping upload the status quo of environmental degradation, climate change, animal suffering, and an unsustainable food system. By classifying animals as consumable resources that are necessary for economic activities and for humans to own and instrumentalize (Plumwood, 1993), schoolbooks frame exploitation and killing as essential. From an anthropocentric and instrumentalist perspective (Brennan & Norva, 2021; Lloro-Bidart, 2015), animals (from the land and sea), vegetables and cereals are labelled resources that “provide” food for humans. The sample shows a clear overvaluation of the need to consume animal-based products as sources of protein. At the same time, there is a clear marginalization of plant-based sources of protein (Cole & Stewart, 2015). For instance, food charts emphasize access to calcium through the ingestion of dairy products while tending to exclude vegetables, grains, nuts, etc. Grains, legumes, lentils, quinoa, peas, and tofu do not appear to be recognized sources of protein. Seeds, nuts, and almonds are not mentioned as sources of omega-3 fatty acids (see Fig. 1). Furthermore, there are no recommendations to reduce the consumption of certain animal-based foods (e.g., red and processed meat) associated with chronic diseases (WCRF, 2007; Oostindjeret et al., 2014; Zhong et al., 2020). Although plant-based diets are recognized by the Portuguese Directorate-General for Health (Silva et al., 2015) as being viable and healthy options, they are not addressed in any national schoolbook.

Animals are mainly depicted as already converted into food, without any mention of the processes of farming and slaughtering. In other words, violent husbandry practices (i.e., deprivation, separation, mutilation and slaughter) remain completely invisible, dissociated from animals. When pictured alive, animals predominantly appear in places that evoke an idyllic countryside, “locavore” farming and the benevolence of “pastoral care” (Stânescu, 2017). Farming is presented as being benign, with no traces of violence (see Fig. 3). However, the depictions of living animals in schoolbooks are in stark contrast to the actual living conditions of such animals in most high income countries: intensive factory farms, where virtually all animals live in confinement and are deprived of freedom and normal behavioural expressions. Schoolbooks ultimately favour the protection of pets, presumably to teach children values associated with care and compassion (see Fig. 4). However, the same principle of care is not applied to factory-farmed animals: their agency is not addressed, nor are they mentioned as subjects who also deserve the moral respect of children.

Although several human activities (e.g., fossil fuels) are identified as causes of environmental problems, there is only a vague mention that correlates animal production with environmental degradation and the poor management of natural resources. Threats to the environment and biodiversity are sometimes presented as being inconvenient for humans (e.g., “noise, and unpleasant smells for populations”) but not for other species and ecosystems. The measures proposed to reduce the human ecological footprint focus on the importance of reducing waste, recycling, adopting the 3Rs and 5Rs policies, saving water in households, using public transport and choosing organic food. However, this pedagogical model still underplays the fact that using water and grain to feed animals, rather than people, is an inefficient way of producing calories (Grainger, 2016) (see Fig. 6).

By avoiding addressing the impacts of the consumption and production of animals, educational materials do not provide primary school students with the necessary tools to effectively cope with the impacts of animal production on the environment and sustainability (see Fig. 8). In these books, there is an instrumentalist approach to animals and a disregard for their agency and intrinsic value. Thus, the reviewed information reinforces the current status quo, i.e., animals as “absent referents” (Adams, 1990), while dissociating students from animal suffering in factory farms and slaughterhouses. Furthermore, children are unable to correlate animal production with environmental degradation and injustice in food distribution despite it being one of the main causes of both. The current dietary representations in the selected sample also devalue healthy plant-based diets as an efficient mechanism for enhancing human health and mitigating impacts on the planet and other living beings.

Recommendations

The fact that educational programmes in Portugal do not adopt transparent conceptual guidelines with respect to the impacts of animal production is part of a broader phenomenon, common among most high income countries, where the beliefs and perceptions surrounding animal consumption are constantly reinforced by the state, private power, the media, and society in general, including educational agents. Thus, it is the responsibility of policy makers and educational agents to use education as an instrument to convey relevant and accurate information and provide students with ways to respond to the contemporary challenges triggered by animal production. Addressing the intrinsic value of, respect for and moral protection of animals while promoting the viability of nutritious and delicious plant-based diets can be a very efficient strategy for tackling climate change, deforestation, soil degradation, unsustainable agriculture, and increases in greenhouse gases and for mitigating the suffering and death of billions of animals.

Rather than praising a productivist, utilitarian and instrumentalist view of nature (see Naess, 1973; Katz, 1991), education ought to value food production based on ethical standards. A more sustainable and eco-centric model (Anderson, 2005; Taylor, 1996) of environmental education pointedly resists the instrumentalization of other species (Brennan & Norva, 2021; Ross, 2020; Thompson, 1994), and such a model should actively implement international recommendations and make the repercussions of the current food model visible. Doing so can foster the development of a more critically informed citizenship that understands the interconnectedness of humans and the environment in food production (Brennan & Norva, 2021; Houde & Bullis, 1999; Lloro-Bidart, 2019). There is a direct correlation between how people perceive animals and the attitudes and behaviours that people exhibit towards them. Only by ascribing rights to sentient animals and by ceasing to interfere with them when human vital needs are not at stake can environmental practices (and education) avoid an unacceptable degree of anthropocentrism (Brennan & Norva, 2021; Lupinacci & Happel-Parkins, 2016; Taylor, 1996).

Indeed, it is important for primary school textbooks to address the consumption of animals as a matter of collective responsibility (Lindgren, 2020) and to correlate such consumption with the impacts of factory farming and industrial fishing. Students should be taught to adopt more socially responsible and sustainable eating practices, involving at least a substantial reduction in the consumption of animal-based products. It is also pertinent to emphasize the importance of plant-based proteins, which are increasingly recognized as a healthy alternative (Silva et al., 2015) that is more sustainable, has a lower ecological footprint (IPCC, 2019) and can provide environmental and human benefits (Grainger, 2016).

Teaching students to adopt more eco-centric and ethical positions and practices necessarily involves fostering inclusion, awareness and compassion towards other living beings. Environmental education ought to open up to a view of animals that takes into account their intrinsic value (Anderson, 2005; Brennan & Norva, 2021), their cognition, and their ability to experience pain and pleasure (Russel, 2019) and relate to other beings (Harfeld, 2011). Fundamental criteria for promoting the interests of animals include subjectivity, the capacity to have propositional attitudes, emotions, the will for freedom of movement, and the right to life (Anderson, 2005; Taylor, 1996). Overall, this criterion should promote a relationship between species where humans are not seen as the only subjects (Adams, 1990; Gaard, 2002; Kheel, 2008; Dinkeret al., 2016; Dolby, 2019).

The analytical procedure applied and the use of the analytical lens of eco-centric environmental ethics theory, ecofeminism, and critical animal studies provide an overview of how significant data (images and texts) from primary school textbooks represent animal production and its impacts on animals, human health and the environment. The findings of this study provide clear evidence that educational programmes in Portugal display worrisome omissions and distortions of the negative consequences of animal production. This article’s central suggestion is to improve current environmental programmes in schools. Here, it could be useful to include educators and scholars who are committed to a model of environmental education that assigns intrinsic value to animals as an essential strategy for tackling environmental degradation, climate change, food insecurity and speciesism. It would be interesting for further research to continue to explore the ways in which animals are depicted within different subjects (e.g., environmental studies, the natural sciences, biology) in primary, secondary and high schoolbooks. Moreover, research should embark on a more thorough investigation of how animals and the impacts of animal production are depicted in university textbooks (e.g., animal science, veterinary science, animal production, animal biology, nutrition, environmental studies). Future studies could also conduct comparative analyses of schoolbooks from diverse territories with similar or dissimilar environmental programmes.

Notes

A Grande Aventura - Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 2; Estudo do Meio 3; Português 3M; Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 3.

Estudo do Meio 3.

Estudo do Meio 4; A Grande Aventura - Estudo do Meio 4.

Na Onda do Português 1; Estudo do Meio 2; Estudo do Meio 3; Estudo do Meio 4; Terra à Vista! Ciências Naturais 6; Português 6; etc.

Estudo do Meio 3; Palavra Puxa Palavra – Português 3; Português 3.

Terra à Vista! Ciências Naturais 6.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 2; Na Onda do Português 1; Estudo do Meio 2; Estudo do Meio 4; A Grande Aventura - Estudo do Meio 4; Cientic 6.

Cientic 6; Terra à Vista! Ciências Naturais 6; Terra Viva. Ciências Naturais 6.

Para férias 6-7 anos. Preparo-me para o 3; Estudo do Meio 1, Estudo do Meio 2; Ciências Naturais-6.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Terra à Vista! Ciências Naturais 6.

Plim! Português 1; Estudo do Meio 3; Estudo do Meio 4; Português 5; Terra Viva - Ciências Naturais 5.

Estudo do Meio 3; Estudo do Meio 4; Terra Viva - Ciências Naturais 5.

Português 3; Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 3.

Estudo do Meio 2.

A Gramática – Português 1; Português 3.

Palavra Puxa Palavra - Gramática da Língua Portuguesa 3 e 4; Português 5.

Estudo do Meio 2; Português 3; Estudo do Meio 4; Português 5; Gramática da Língua Portuguesa – 2º Ciclo.

Palavra Puxa Palavra - Gramática da Língua Portuguesa 3 e 4; Português 5.

Português 5.

Plim! Português 1.

Estudo do Meio 3.

Estudo do Meio 3; Estudo do Meio 4; Ciências Naturais 5.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 3.

Dito e Feito - Português 6.

Dito e Feito - Português 6.

Ciências Naturais 5.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Ciências Naturais 5.

Estudo do Meio 3.

Estudo do Meio 2; Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 4; A Grande Aventura; Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 2; Preparar as Provas de Aferição 2; Estudo do Meio 4; Novo Despertar – Estudo do Meio 4.

Estudo do Meio 4.

Dito e Feito – Português 6.

References

Adams, C. J. (1990). The sexual politics of meat: A feminist-vegetarian critical theory. Continuum.

Adams, C. J. (1995). Do feminists need to liberate animals, too? On the Issues Dialogue., 4, 2.

Anderson, E. (2005). Animal rights and the values of nonhuman life. In Sunstein, C. R., Nussbaum, M. C. Animal Rights: Current Debates and New Directions. Oxford Scholarship Online. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195305104.001.0001

Arken, M. M. (1989). Environmental education, children and animals. Anthrozoӧs, 3(1), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279390787057810

Brennan, A., Norva Y. S. L. (2021). Environmental Ethics. In Edward N. Zalta (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/ethics-environmental/>

Brooks-Pollock, E., de Jong, M. C. M., Keeling, M., James, K. D., & Wood, J. L. N. (2015). Eight challenges in modelling infectious livestock diseases. Epidemics, 10, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2014.08.005

Câmara, A. C., Proença, A, Teixeira, F., Freitas, H., Gil, H. I., Vieira, I., Pinto, J. R., Soares, L., Gomes, L., Gomes, M., Gomes, M., Amaral, M. L., Castro, S. T. (n.d.). Referencial de Educação Ambiental para a Sustentabilidade para a Educação Pré-Escolar, o Ensino Básico e o Ensino Secundário. Ministério da Educação. Retrieved from: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/ECidadania/Educacao_Ambiental/documentos/referencial_ambiente.pdf

Cole, M., Stewart, K. (Eds.) (2015). Our children and other animals (the cultural construction of human-animal relations in childhood). Ashgate.

D'Eaubonne, F. (1974). Le Féminisme ou la mort. Édition Le Passager Clandestin: Champagne.

Dinker, K. G., & Pedersen, H. (2016). Critical animal pedagogies: Re-learning our relations with animal other. In H. E. Lees & N. Noddings (Eds.), The Palgrave International Handbook of Alternative Education (pp. 415–430). Palgrave Macmillan.

Dolby, N. (2019). Nonhuman animals and the future of environmental education: Empathy and new possibilities. The Journal of Environmental Education, 50(4–6), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2019.1687411

Donovan, J. (1990). Animal rights and feminist theory. Signs, 15(2), 350–375. https://doi.org/10.2307/3174490

European Convention for the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes. (2009). Article 4.1. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/animals/docs/aw_european_convention_protection_animals_en.pdf.

Eur-Lex. (2008). Council Directive 2008/120/EC of 18 December 2008 laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. European Union. Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32008L0120.

FAO—Food and Agriculture Organization. (2006). Livestock´s long shadow – environmental issues and options. United Nations. Retrieved from:http://www.fao.org/3/a0701e/a0701e00.htm.

FAO—Food and Agriculture Organization. (2013). Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock. United Nations. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/resources/en/publications/tackling_climate_change/index.htm.

Gaard, G. (2017). Critical ecofeminism. Lexington Books.

Gaard, G. (2002). Vegetarian ecofeminism: A review essay. Frontiers, 23(2), 14.

Gaard, G., & Gruen, L. (1993). Ecofeminism: Toward global justice and planetary health. Society and Nature, 2, 1–35.

Gaard, G., & Murphy, P. D. (Eds.). (1998). Ecofeminism literary criticism: Theory, interpretation, pedagogy. University of Illinois Press.

Garnett, G. (2010). Livestock and Climate Change. In J. D’Silva & J. Webster (Eds.), The meat crisis: Developing more sustainable production and consumption (pp. 34–56). Earthscan.

Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G. (2013). Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Grainger, M. (2016). Flexitarianism: flexible or part-time vegetarianism. United Nations. Retrieved from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=2252

Harfeld, J. (2011). Husbandry to industry: Animal agriculture, ethics and public policy. Between the Species, 13(10), 132–162. https://doi.org/10.15368/bts.2010v13n10.9

Houde, L. J., & Bullis, C. (1999). Ecofeminist pedagogy: An exploratory case. Ethics and the Environment, 4(2), 143–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1085-6633(00)88417-X

Hudson, S. J., & Mullord, M. M. (1977). Investigations of maternal bonding in dairy cattle. Applied Animal Ethology, 3(3), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3762(77)90008-6

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2019). Climate Change and Land – Special Report. United Nations. Retrieved from: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/.

Jamieson, D. (1998). Animal liberation is an environmental ethic. Environmental Values, 7(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327198129341465

Katz, E. (1991). Restoration and redesign: The ethical significance of Human intervention in Nature. Restoration and Management Notes, 9, 90–96.

Kheel, M. (2008). Nature ethics: an ecofeminist perspective. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Kronlid, D. O., & Öhman, J. (2013). An environmental ethical conceptual framework for research on sustainability and environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 19(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.687043

Leopold, A. (1949). A sand county almanac. Oxford University Press.

Lindgren, N. (2020). The political dimension of consuming animal products in education: an analysis of upper-secondary student responses when school lunch turns green and vegan. Environmental Education Research Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1752626

Liu, G., Zong, G., Wu, K., Hu, Y., Li, Y., Willet, W. C., Eisenberg, D. M., Hu, G. B., & Sun, Q. (2018). Meat cooking methods and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from three prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Journal. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1992

Lloro-Bidart, T. (2015). A political ecology of education in/for the anthropocene. Environment and Society, 6(1), 128–148. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2015.060108

Lloro-Bidart, T. (2019). The bees wore little fuzzy yellow pants: Feminist intersections of animal and human performativity in an urban community garden. In B. Parker, J. Brady, E. M. Power, & S. Belyea (Eds.), Feminist food studies: Intersectional perspectives (pp. 33–56). Women’s Press.

Lloro-Bidart, T., & Banschbach, V. (2019). Animals in environmental education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lupinacci, J., & Happel-Parkins, A. (2016). (Un)Learning anthropocentrism: An ecoJustice framework for teaching to resist human-supremacy in schools. In S. Rice & A. G. Rud (Eds.), The educational significance of human and non-human animal interactions (pp. 13–29). Palgrave Macmillan.

Naess, A. (1973). The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement: A summary. Inquiry an Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy, 16(1–4), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00201747308601682

Noske, B. (1989). Humans and other animals: Beyond the boundaries of anthropology. Pluto Press.

Oakley, J. (2019). What can an animal liberation perspective contribute to environmental education? In T. Lloro-Bidart & V. S. Banschbach (Eds.), Animals in environmental education. Palgrave.

Oostindjeret, M., et al. (2014). The role of red and processed meat in colorectal cancer development: A perspective. Science Direct, 97(4), 583–596.

Pachirat, T. (2011). Every twelve seconds (industrialized slaughter and the politics of sight). Yale University Press.

Pedersen, H. (2010). Animals in schools. Processes and strategies in human-animal education. Purdue University Press.

Plumwood, V. (1993). Feminism and the mastery of nature. Routledge.

Rawles, K. (2017). The meat crisis: Developing ethical. Routledge.

Ross, N. (2020). Anthropocentric tendencies in environmental education: A critical discourse analysis of nature-based learning. Ethics and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2020.1780550

Russel, J. (2019). Attending to nonhuman animals in pedagogical relationships and encounters. In T. Lloro-Bidart & V. Banschbach (Eds.), Animals in environmental education (pp. 117–137). Palgrave.

Silva, S., Gomes, C, Pinho, J. P., Borges, C., Santos, C. T., Santos, A., Graça, P. (2015) Linhas de orientação para uma alimentação vegetariana saudável. Direção-Geral da Saúde. Retrieved from: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/80821/3/44969.pdf

Spannring, R. (2017). Animals in environmental education research. Environmental Education Research, 23(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1188058

Stânescu, V. (2017). New weapons: ‘humane farming’, biopolitics and the post-commodity fetish. In D. Nibert (Ed.), Animal Oppression and Capitalism. Praeger.

Taylor, A. (1996). Animal rights and human needs. Environmental Ethics., 18(3), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics199618316

Taylor, N., Twine, R. (Eds.) (2014). The rise of critical animal studies: From the margins to the centre (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203797631

Timmerman, N., & Ostertag, J. (2011). Too many monkeys jumping in their heads: Animal lessons within young children’s media. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 16, 54–70.

Thompson, P. B. (1994). The spirit of the soil: Agriculture and environmental ethics. Routledge.

Twine, R. (2010). Animals as biotechnology: Ethics, sustainability and critical animal studies. University of Oxford.

Waldau, P. (2013). Venturing beyond the tyranny of small differences: The animal protection movement, conservation, and environmental education. In M. Bekoff (Ed.), Ignoring nature no more: The case for compassionate conservation (pp. 27–44). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Warren, K. J. (1987). Feminism and ecology: Making connections. Environmental Ethics, 9, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics19879113

WCRF (World Cancer Research Fund). (2007). Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research. Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/4841/1/4841.pdf

Young, R. (2010). Does organic farming offer a solution? In J. Dsilva & J. Webster (Eds.), The meat crisis: Developing more sustainable production and consumption (pp. 80–96). Routledge.

Zhong, V., Horn, L. V., & Greenland, P. (2020). Associations of processed meat, unprocessed red meat, poultry, or fish intake with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Jama Internal Medicine, 180(4), 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6969

Acknowledgements

I m thankful to REUTILIZAR movement for providing the sample for this study. I´m also thankful to the reviewers who provided pertinent feedback to improve this article. This study was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), RD Unit UIDB/03126/2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Index- List of (primary) schoolbooks included in the sample.

Ana Albuquerque e Aguilar, Catarina Carvalheiro, Vera Batista (2016) Ponto por Ponto. Caderno de Atividades—Português 5. Texto Editores.

Ana Albuquerque e Aguilar, Ana Santiago, Sofia Paixão (2017) Palavra-Passe—Português 6. Texto Editores.

Ana Lemos, Cristina Cibrão, José Salsa, Rui Cunha (2020) Cientic 5—Ciências Naturais. Caderno do aluno”. Porto Editora.

Ana Lemos, Cristina Cibrão, José Salsa, Rui Cunha (2020) Cientic 5—Ciências Naturais”. Porto Editora.

Ana Lemos, Cristina Cibrão, José Falsa, Rui Cunha (2020) Cientic 6—Ciências Naturais”. Porto Editora.

Ana Santiago, Sofia Paixão (2016) Caderno de Atividades Palavra Mágica 5. Editora Texto.

Ana Santiago, Sofia Paixão (2016) Palavra Mágica—Português 5. Texto Editores.

Ana Simões, Ema Sá Barros, Joana Faria, Silvina Fidalgo (2016) “Palavra Puxa Palavra—Português 5. Editores Asa.

Abel Mota, Maria João Pereira, Paula Ferreira (2020) “Palavras 5—Português. Areal Editores.

Angelina Rodrigues, António Marcelino, Cláudia Pereira, Luísa Azevedo (2020) “Estudo do Meio 2”. Areal.

Ana Maria Bayan Ferreira, Helena José Bayan (2011) “Na Onda do Português 1”. Editora Lidel.

Carlos Letra, Ana Margarida Afreixo (2015) O Mundo da Carochinha—Português 2. Editora Gailivro.

Carlos Letra, Miguel Borges (2014) O Mundo da Carochinha—Português 2. Editora Gailivro.

Carlos Letra, Ana Margarida Freixo (2011) Estudo do Meio 3. Editora Gailivro.

Carlos Letra, Ana Margarida Freixo (2011) Estudo do Meio 4. Editora Gailivro.

Eva Lima, Nuno Barrigão, Nuno Pedroso, Susana Santos (2012) Estudo do Meio 1. Porto Editora.

Eva Lima, Nuno Barrigão, Nuno Pedroso, Vítor da Rocha (2017) Estudo do Meio 2. Porto Editora.

Eva Lima, Nuno Barrigão, Nuno Pedroso, Vítor da Rocha (2020) Estudo do Meio 4. Porto Editora.

Fernanda Costa, Lídia Bom (2020) Caderno de Atividades. Livro Aberto. Português 5. Porto Editora.

Fernanda Costa, Lídia Bom (2020) Livro Aberto. Português 5. Porto Editora.

Fernanda Costa, Luísa Mendonça (2015) Diálogos 6—Caderno de Atividades. Porto Editora.

Fernanda Costa, Lídia Bom (2017) Livro Aberto. Português 6. Porto Editora.

Fernanda Neves, Sandra Gaspar (2014) Já Fizeste os TPC? Português, Estudo do Meio, Matemática 2. Editora Areal.

Fernanda Neves, Sandra Gaspar (2019) Já fizeste os TPC? Português, Estudo do Meio, Matemática 3″. Areal Editores.

Francisco Martins (2013) Palavra Puxa Palavra—Gramática da Língua Portuguesa 3 e 4. Edições Livro Directo.

Hortência Neto (2012) Novo Despertar—Estudo do Meio 4. Edições Livro Direto.

Isabel Borges, Cláudia Pereira (2020) Português 3. Areal.

Isabel Caldas, Maria Isabel Pestana (2016) Terra Viva. Ciências Naturais 5. Edição Santillana.

Isabel Caldas, Maria Isabel Pestana (2016) Terra Viva. Ciências Naturais 5. Volume 2. Edição Santillana.

Isabel Caldas, Maria Isabel Pestana (2017) Terra Viva. Ciências Naturais 6. Edição Santillana.

Jacinta Rosa Moreira, Vítor Nuno Pinto, Quitéria Coelho (2020) Ciências Naturais 6. Areal Editores.

Lucinda Motta, Maria dos Anjos Viana, Ilídio André Costa, José Américo Barros, Rui Polónia Santos (2020) Terra à Vista! Ciências Naturais 6. Porto Editora.

Maria do Céu Vieira Lopes (2012) Gramática da Língua Portuguesa—2º Ciclo. Plátano Editora.

Maria Helena Marques, Maria Regina Rocha (n/d) A Gramática—Português 1. Porto Editora.

Marisa Costa, Paula Melo (2016) Plim! Português 1. Texto Editores.

Marisa Costa (2017) Preparar as Provas de Aferição 2. Editora Texto.

Maria José Marques, Luísa Pinto (2013) Desafios—Português 4. Editora Santillana.

Maria Helena Marques, Maria Regina Rocha. (2014) A Gramática—Português 1. Porto Editora.

Paula Pires, Henriqueta Gonçalves, Ana Landeiro (2013) A Grande Aventura—Estudo do Meio 4. Texto Editores.

Pedro Silva, Sofia Rente, Elsa Cardoso (2015) Dito e Feito—Português 6. Porto Editora.

N/A (2017) Para férias 6–7 anos. Preparo-me para o Terceiro ano 2. Porto Editora.

N/A (2012) Testes—Ciências da Natureza 5. Edições Asa.

N/A (2019) Cadernos de Revisão 5. Porto Editora.

N/A (2014) Prova Final Segundo Ciclo—Português 6. Editora Educação Nacional.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fonseca, R.P. The Impacts of Animal Farming: A Critical Overview of Primary School Textbooks. J Agric Environ Ethics 35, 12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-022-09887-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-022-09887-2