Abstract

COVID-19 underscores the importance of understanding variation in adherence to rules concerning health behaviors. Children with conduct problems have difficulty with rule adherence, and linking early conduct problems with later adherence to COVID-19 guidelines can provide new insight into public health. The current study employed a sample (N = 744) designed to examine the longitudinal consequences of childhood conduct problems (Mean age at study entry = 8.39). The first objective was to link early conduct problems with later adherence to both general and specific COVID-19 guidelines during emerging adulthood (M age = 19.07). The second objective was to prospectively examine how interactional (i.e., callous unemotional traits, impulsivity) and cumulative (i.e., educational attainment, work status, substance use) continuity factors mediated this association. The third objective was to examine differences in sex assigned at birth in these models. Direct associations were observed between childhood conduct problems and lower general, but not specific COVID-19 guideline adherence. Conduct problems were indirectly associated with both general and specific adherence via higher levels of callous unemotional traits, and with specific adherence via higher problematic substance use. No differences in the models were observed across sex assigned at birth. Findings provide insight into both how developmental psychopathology constructs are useful for understanding COVID-19 guideline adherence, and the ways in which conduct problems may shape health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly influenced lives around the world. Prior to the availability of effective vaccines or treatments, the best methods for reducing infection rely on individuals following public health guidelines regarding physical distancing, hand washing, and mask wearing (Wiersinga et al., 2020). The Centers for Disease control indicate that young adults are increasingly involved with the spread of the virus (CDC, 2020), suggesting the importance of understanding COVID-19 regulation adherence within this age group. One of the many contributions that developmental science can make is in identifying the individual differences that explain adherence to public health directives. Children with conduct problems are children who are at risk or meet criteria for conduct disorder and/or comorbid oppositional defiant disorder (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). While conduct problems are associated with difficulty across multiple domains, the importance of rule-breaking and social norms violations for conduct problems highlights how this particular type of problem behavior may be uniquely pertinent in the prediction of adherence to COVID-19 guidelines. We focus on how conduct problems are prospectively associated with adherence to COVID-19 guidelines, and identify interactional (i.e., callous unemotional traits and impulsivity) and cumulative (i.e., education, employment and substance use) continuity mechanisms that mediate this association.

COVID-19 Guideline Adherence

Individual differences are linked to following medical recommendations (DiMatteo, 2004a, b; DiMatteo et al., 2007; Molloy et al., 2014). For COVID-19 specifically, focusing on adherence among young adults is particularly important, as while COVID-19 infection can be serious for emerging adults (Swann et al., 2020), much of the focus has been on young adults’ capacity to spread the disease to medically vulnerable populations (Wan & Balingit, 2020). Existing research on COVID-19 guideline adherence has focused on individual health compliance behaviors (Nowak et al., 2020; O’Connell et al., 2020), composite scales assessing multiple health compliance behaviors (Miguel et al., 2021; Nivette et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020), or general adherence (i.e., questions as to whether the individual is generally following COVID-19 related guidelines) (Zajenkowski et al., 2020). The emerging nature of this field underscores the use of multiple perspectives for examining COVID-19 guideline adherence.

Conduct Problems and COVID-19 Guideline Adherence: A Developmental Framework

We argue that conduct problems may be relevant for understanding later COVID-19 guideline adherence because conduct problems are associated with poor general adherence to rules and social norms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). We propose that understanding how childhood conduct problems may put individuals at risk for failing to adhere to COVID-19 guidelines can best be explained in two parts. First, following from Life Course theory more broadly (Elder, 1998), Life Course Health Development Framework (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002) situates behaviors (such as adherence to health-related guidelines) within a nested, multi-level, and developmental framework. The developmental aspect of this theoretical framework suggests the importance of situating COVID-19 compliance, and the role of conduct problems in this compliance, in specific stages of the life course. Individuals whose conduct problems start in childhood are particularly at risk for negative outcomes, including those related to rule breaking and poor health (Odgers et al., 2008; Rivenbark et al., 2018). This approach also underscores the importance of focusing on emerging adulthood for understanding compliance with COVID-19 behaviors, as emerging adults generally have greater independence than adolescents (Arnett, 2000), but broader social networks than other adults (Wrzus et al., 2013).

Second, Caspi et al. (1987) propose interactional and cumulative continuity as two mechanisms for explaining why externalizing-type behaviors like conduct problems have consequences across the life course. Starting with interactional continuity (Caspi et al., 1987), this more proximal process describes how traits inherent to a behavior are reinforced by the consequences of this behavior, thus maintaining the trait, and associated behavior patterns, across time. In identifying interactional continuity factors, stable traits endemic to the problematic behavior pattern can be tested as mediators. Many traits are linked with conduct problems. In focusing on a rule-breaking associated outcome (i.e., COVID-19 guideline adherence), however, callous unemotional traits and impulsivity are central to conduct problems, show stability across time (Viding & McCrory, 2012), and are both longitudinally associated with higher levels of rule-breaking behavior (Forsman et al., 2010; Maneiro et al., 2017).

Callous unemotional traits refer to a pattern of behavior whereby the individual shows a lack of guilt or remorse, little concern for the feelings of others, shallow or superficial emotions and lack of concern regarding performance, a pattern of traits that are a developmental precursor for psychopathy (Frick et al., 2014b). Callous unemotional traits are central for understanding the emergence and persistence of the most serious forms of conduct problems (Frick et al., 2014a; Longman et al., 2016). Callous unemotional traits are additionally linked with higher rates of rule-breaking behaviors that have health consequences for both the individual and others (Thornton et al., 2019). Finally, a growing literature with non-clinical samples of adolescents and adults has found that higher levels of antisocial traits (Miguel et al., 2021; Nivette et al., 2020; Nowak et al., 2020; O’Connell et al., 2020), including callous unemotional traits (Miguel et al., 2021), are linked with lower levels of COVID-19 guideline adherence

Impulsivity, or the extent to which an individual responds to novel stimuli in a rapid and unplanned way, without considering the consequences of those reactions (Stanford et al., 2009). While impulsivity is associated with a variety of psychopathology constructs (most notably attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders), it also shows stability across childhood, and is an important predictor of the emergence of later conduct problems (Olson et al., 1999). Impulsivity, moreover, is also associated with worsening conduct problems when controlling for initial levels of conduct problems (Fanti et al., 2018). This construct is associated with outcomes for individuals with conduct problems, including rule-breaking behavior (Maneiro et al., 2017), and in general is associated with health risk behaviors that place the individual and others at risk like unprotected sex (Dir et al., 2014) and risky driving behavior (Bıçaksız & Özkan, 2016).

Cumulative continuity refers to processes whereby the consequences of the behavior pattern (for instance the aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors associated with conduct problems) direct the individual towards environments that further exacerbate these preexisting tendencies (Caspi et al., 1987). Identifying and testing cumulative continuity involves prospectively linking the behavior to the outcomes of the behavior, and then examining how these consequences mediate the association between the childhood behavior and later outcomes. The classic example of cumulative continuity is in how conduct problems are associated with greater difficulty in navigating educational and occupational systems, and may explain how conduct problems may shape COVID-19 guideline adherence. In this pathway, conduct problems heighten the risk for drop out, and increase the likelihood of later types of employment in which the individual has less autonomy and stability, and more stress (Caspi et al., 1987). The link between conduct problems and both poorer school outcomes and lower occupational status are well established (Erskine et al., 2016), as is the subsequent link between these indicators of socioeconomic status and other types of medical guideline adherence (DiMatteo, 2004b). The link between conduct problems or components of conduct problems and other health outcomes, moreover, have been fully or partially accounted for by educational attainment (Sagatun et al., 2015; Temcheff et al., 2011).

The educational and occupational consequences of conduct problems may be particularly important for understanding adherence with COVID-19 related guidelines. Higher levels of education may help an individual parse complex and rapidly evolving information, as education-related factors like medical literacy and numeracy are linked with other forms of medical adherence (Brown & Bussell, 2011). Higher levels of education are also associated with lower belief in conspiracy theories in general, and COVID-19 conspiracies particularly (van Prooijen, 2017), which are linked with COVID-19 guideline adherence (Soveri et al., 2020). Furthermore, occupational status-related factors may allow individuals to choose work contexts with less COVID-19 exposure, shaping their guideline adherence, underscoring the importance of exploring the role of cumulative mechanisms.

Problematic substance use is another cumulative mechanism linking conduct problems to later outcomes. Childhood conduct problems are one of the most consistent predictors of later substance use problems (Stone et al., 2012), and substance use problems are linked with poorer medical adherence (Parsons et al., 2014), including among emerging adults (Glasgow et al., 1991). Indeed, problematic substance use may be anticipated to impair the organization and planning required to follow public health guidelines.

Gender Differences

Finally, understanding how childhood histories of conduct problems are associated with adherence to COVID-19 guidelines may be anticipated to vary across gender. Gender paradox theory suggests that while boys are more likely to have conduct problems than girls, the consequences of conduct problems are more severe among girls (Loeber & Keenan, 1994). Indeed, the consequences of conduct problems in terms of substance use (Loeber & Keenan, 1994; Pedersen et al., 2001) and adult violent behavior (Reef et al., 2011), may be greater for girls than boys, although not all findings confirm significant gender differences (Fergusson et al., 2005; Wertz et al., 2018). With regards to COVID-19 guideline adherence, some research suggests that women are generally more likely to adhere to public health guidelines than men in normative samples (Nivette et al., 2020; Zajenkowski et al., 2020), although these differences are not large and other work finds no significant differences (O’Connell et al., 2020).

The Current Study

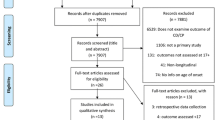

Using a longitudinal sample of participants recruited in childhood to understand the developmental course of conduct problems, the present study had three objectives. The first was to understand how childhood conduct problems were associated with both general and specific adherence to public health guidelines during the initial lockdown phase of the COVID-19 pandemic among emerging adults. We expected that conduct problems would be associated with lower levels of adherence to COVID-19 guidelines. The second objective was to assess how both interactional (i.e., impulsivity and callous unemotional traits) and cumulative (i.e., education, occupation and substance use) mechanisms mediated between childhood conduct problems and emerging adulthood COVID-19 guideline adherence (see Fig. 1). We expected that both interactional and cumulative mechanisms would mediate between conduct problems and COVID-19 guideline adherence. Finally, the third objective was to test if these associations varied according to gender, where we anticipated the links between conduct problems and COVID-19 adherence to be stronger among women than among men. Informed by developmental psychopathology theory, examining if and how conduct problems are linked to adherence to COVID-19 guidelines provides vital information for addressing this public health crisis, as well as for understanding the health outcomes of childhood conduct problems.

Method

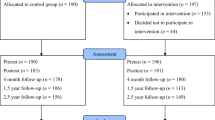

Data from a longitudinal study comparing children with and without early histories of conduct problems in four regions of Quebec, Canada (N = 744; 47% girls; 58% with histories of conduct problems) were employed. The Ethics Research Committee of the Université de Sherbrooke approved all waves of data collection. Parent written consent and child verbal assent were obtained at the first wave of data collection, written consent was obtained from both parents and participants for the adolescent waves of data collection, and participant consent was obtained over the telephone for the COVID-19 data collection. Two participant recruitment strategies were employed to ensure sufficient power to compare children with and without conduct problems. First, the majority of the sample presenting with conduct problems was recruited based on receiving services for conduct problems within public elementary schools, reflecting 95% of children in Quebec (Government of Quebec, 2013). All girls and one in four boys (chosen at random) receiving services in 155 French language schools were invited to participate. A total of 75.1% of those invited agreed to participate (n = 370), and no significant differences were observed for participation in terms of gender, grade, or school socioeconomic status. Children were evaluated by their parents or teachers using the DSM-Oriented Scales for Conduct Problems or for Oppositional Defiant Problems of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). This assessment revealed that 339 of the 370 children were in the borderline or clinical range of conduct problems or oppositional defiant problems scales (above the 93th percentile).

In Quebec, children are generally referred for services by teachers. To address concerns about teacher biases in service referrals, a second recruitment strategy designed to identify children with conduct problems not referred to services was employed. A total of 881 students from schools in low income neighborhoods were assessed by their parents and teachers using the Conduct Problems and the Oppositional Defiant Problems DSM-Oriented Scales of the ASEBA (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), and participants who were in the borderline or clinical range were invited to participate (n = 95, 57.9% girls). One out of every three children who were in the normal range of the scales but were age, gender and location matched with children in the conduct problem sample were also recruited at this time (n = 279). In total 93.5% of the sample were born in Quebec, with the majority being of French-Canadian origin.

Every year for the next twelve years, participants completed a variety of measures in their homes. For the most recent data collection, focusing on participant experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were between 16 and 22 years of age (M = 19.07, SD = 1.20). Participants were contacted by telephone and completed the measures for the COVID-19 data collection 51 and 68 days following a declaration of a public health emergency in Quebec on March 13th, 2020, which was during the initial wave of the pandemic in Canada. Quebec is an ideal location for understanding how and when individuals followed COVID-19 related public health guidelines. At the time of the study, Quebec was the epicenter of COVID-19 within Canada, with nearly half of Canada’s overall cases. Quebec consists of different administrative regions, however, that varied widely in COVID-19 rates. For the duration of the COVID-19 data collection, schools, daycares, as well as all non-essential services (e.g., restaurants, hair salons, and gyms) were closed, and citizens were given strict public health guidelines designed to curb the spread of the virus.

Measures

Two different assessments of COVID-19 adherence were employed. The first was a single question regarding general adherence where participants were asked “since the 13th of March, to what extent have you generally changed your habits and behaviors to avoid catching or transmitting the COVID-19 virus?” Options ranged from 1 (not very much) to 5 (very much), with higher scores indicating higher levels of adherence (descriptive presented in Table 1). While asking about general adherence was important, we also wanted to understand specific adherence to COVID-19 related guidelines. Participants answered thirteen questions (presented in Table 1 of the Appendix) regarding adherence to different public health guidelines outlined by the province of Quebec (Santé Public, 2020). Given the changing nature of the public health directives some forbidden behaviors that were later permitted (i.e., spending time with individuals outside) were included. Similarly, initial directives did not recommend the use of masks, which explained the low levels of adherence for this item. Conversely, given the importance of mask wearing for later adherence, we chose to retain this item for the total scale.

Because we wanted to both (1) capture a range of health behaviors and (2) be as specific as possible in terms of adherence, having the same response options for each item on the scale was impractical (see Appendix Table 1), and three response option patterns were used. The first assessed situations in which adherence could be measured according to the frequency of the behavior (i.e., handwashing in response to contact with others), with five response options ranging between always and never. The second set of response options captured the number of times an individual engaged in a quotidian behavior that was now restricted (i.e., going to the store). Options reflected the number of times in a week an individual engaged in the behavior, with options ranged from every day to never. The third set of responses reflected occasional behaviors (i.e., using services that were supposed to be closed but were open illegally) and the five response options varied from “whenever I have the opportunity” to “never.” Most item responses were not evenly distributed and were dichotomized to reflect compliance (or not) with the public health directives. In almost all cases, questions were dichotomized according to the never/always response. The exception to this overall strategy was with question eight (which assessed going to the store). As people were permitted to use essential services (i.e., grocery stores, pharmacies) once a week, this question was dichotomized at 1-2 a week or less compared with other options. The scale constructed from summing these variables had a tetrachoric alpha of .81 (Gadermann et al., 2012), with higher values indicating higher levels of adherence.

Conduct problems were assessed using the Conduct Problems and the Oppositional Defiant Problems DSM-Oriented Scales of the ASEBA at the initial testing period (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Ebesutani et al., 2010). The Conduct Problems subscale includes 17 items for parents and 13 items for teachers, and had Cronbach’s alphas of 0.93 and 0.87, respectively, in this sample. The Oppositional Defiant problems subscale includes five items for teachers and parents, and had Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 and 0.92, respectively, in this sample. As the sample was based on participants being in the borderline or the clinical ranges (above the 93th percentile) or not as assessed by either parents or teachers, we classified all children according to whether they were or were not in the borderline or the clinical ranges for each of these four subscales (i.e., dichotomous score was constructed). These four dichotomous variables were loaded onto a factor as the measure of conduct problem status, with higher scores indicating higher levels of problem behavior (factor structure presented in results section). As a sensitivity check, models employing alternate constructions of the behavior problems variable were tested (see Appendix Table 2), with results consistent with the operationalization of conduct problems presented.

Mediating variables were collected during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Callous-unemotional traits were assessed using the parent-reported Antisocial Process Screening Device (Deshaies et al., 2009; Frick & Hare, 2001). This commonly used scale includes six items and had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.67 in the current sample, with higher scores indicating higher levels of callous unemotional traits. These traits were assessed at time six when participants were ages 11-15 years (M = 13.23, SD = 0.96). Callous unemotional traits are stable in general, with particular stability being noted among youth high in callous unemotional traits compared to youth with lower levels of this trait (Bégin et al., 2020; Fanti et al., 2017).

Impulsivity was assessed using the total score from the Barratt Impulsivity Scale-II (BIS: Patton et al., 1995). This self-report scale includes 30 items and had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 in the current study, with higher scores indicating higher impulsivity, and shows stability over time (Niv et al., 2012). Impulsivity was assessed at time eight when the participants were between the ages of 13 and 17 years (M = 15.32, SD = 0.96), the only time point in which participants completed this measure.

Education and Occupation

Adherence to COVID-19 guidelines may also be shaped by the types of activities required of participants during the pandemic. We asked participants about their current work situation (i.e., were they in school, teleworking, working outside the home or neither working nor in school), where participants could select multiple options (i.e., in school and working). Individuals were coded as being working outside the home or not and in school/college/university or not (answer yes or no), with the higher value indicating participation in the specified activity during the COVID-19 assessment period, when participants ranged in age from 18 to 22 (M = 19.07, SD = 1.20).

Problematic substance use was assessed using the Grille de dépistage de consommation problématique d'alcool et de drogues chez les adolescents et les adolescentes (DEP-ADO: Germain et al., 2007). The DEP-ADO is a self-report assessment of problematic alcohol and drug use among adolescents (Landry et al., 2004). This scale contains six questions with sub-questions relating to substance use and its consequences. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients vary between 0.85 and 0.87 for the total score (Landry et al., 2004), with higher scores indicating higher levels of problematic substance use. This measure was also administered at time eight.

Control Variables

We also expected that the associations between conduct problems, adolescent and young adult mediators, and COVID-19 adherence would be confounded by both demographic factors and factors associated with probable exposure to COVID-19. To start, sex assigned at birth was assessed based on parent-reported child sex at the start of the study (options: boy or girl). Age was assessed by subtracting the child’s date of birth from the date of study participation at time 1. Family socioeconomic status was assessed using both primary caregiver education (self-report, and dichotomized based the primary caregiver having completed high school or not) and family income. Family annual income was assessed using an adaptation of a 20-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 (C$0-999) to 20 (more than C$160,000) that was adjusted to normalize the distribution (Valla et al., 1994). Childhood cognitive functioning was estimated in the initial testing period with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT: Dunn et al., 1993), a measure of receptive vocabulary that is highly correlated with other measures of cognitive functioning (Hodapp & Gerken, 1999). This test was administered by a research assistant and consists of 170 multiple-choice cards where children identify the image associated with the word, with higher score indicating larger vocabularies.

COVID-19 Variables

COVID-19-specific factors were expected to influence the likelihood of COVID-19 regulation adherence. As rates of COVID-19 infection differed across administrative regions of Quebec, we controlled COVID-19 deaths per region by using the province of Quebec’s estimates of deaths per 100 000 residents on the 22nd of May, 2020, the day following the end of data collection. While we initially planned to nest individuals within region, interclass correlations suggested that a non-significant amount of variance was accounted for by region for both general adherence (0.01% of the variance, n.s.) and specific adherence (1.20 % of the variance, n.s.), we elected to control for deaths per region, as a continuous variable, instead. Finally, we also anticipated that COVID-19 guideline adherence would be associated with the individual’s COVID-19 exposure. While none of the participants reported being diagnosed with COVID-19, also we asked participants if they had been advised by public health officials to quarantine, coded “had been advised to quarantine” or not, with not being advised to quarantine as the referent category.

Analytic Plan

Prior to the analyses addressing the primary research question, the structure of the conduct problems factor was tested using MPlus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The primary research objectives were then tested using structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM has numerous advantages in that it allows for an exploration of the associations between both latent (i.e., conduct problem status) and observed (i.e., COVID-19 adherence) variables, permits for multiple outcome variables (i.e., general and specific adherence), and includes the assessment of both direct and indirect pathways between variables. In particular, Mplus can be used to calculate indirect effects using the product of the coefficient approach (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Bootstrapping (done 1000 times) was employed (Bollen & Stine, 1990; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). MPlus also allows pathways in SEMs to be constrained to compare model fit across different groups (i.e., the ability to test the model for differences according to sex assigned at birth) to address the third objective. We used the same approach to test if differences could be observed in the association between predictor variables and the two different outcome variables (i.e., to test if the respective associations between a predictor variable differed across the two COVID-19 guideline adherence outcomes). Finally, Mplus addresses missing data using full information maximum likelihood (Allison, 2001). Although only 9% of the data were missing overall, retaining cases with no missing values would have resulted in the retention of only 60% of the sample (missing data by variable is presented in Table 1).

The two models tested all four classic mediation steps (Baron & Kenny, 1986), and also included indirect effects in line with more modern mediation approaches, which do not necessitate direct effects between the predictor and outcome variables (MacKinnon, 2008). Model 1 tested the first step in a mediation, where we established (1) the association between the predictor (conduct problems) and outcome (COVID-19 guideline adherence) variables. Model 2 tested the second, third, and fourth steps of a mediation. We examined the association between the predictor (conduct problems) and the mediators (school status, work status, callous unemotional traits, substance use, and impulsivity). In the same model, we also tested the associations between the mediators (school status, work status, callous unemotional traits, substance use, and impulsivity) and the outcome variables (COVID-19 guideline adherence). Finally, we examined change in the association between the predictor and outcome variables when the mediators were included, and tested the indirect effects between conduct problem status and both general and specific adherence (MacKinnon, 2008). In line with the third objective, all models were constrained and compared according to sex assigned at birth.

Results

Prior to testing the models, we assessed the factor structure for conduct problem status. The initial factor structure was poor (Chi2 (2) =166.51, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.33 (90% CI: 0.29, 0.38), CFI = 0.84, TLI = 0.50), reflecting the shared variance between the two parent and teacher-rated problem behaviors, respectively. The subsequent factor accounting for this variance showed good fit (Chi2 (0) = 14.92, p < 0.01 RMSEA = 0.00, (90% CI: 0.00, .00) CFI = 0.99; TLI = 1.00), with factor loadings ranging from 0.53 to 0.79 (all significant).

Conduct Problems and COVID-19 Guideline Adherence

The subsequent model examined associations between conduct problems and the two adherence outcomes, controlling for sex assigned at birth, age, cognitive functioning, parental education, family income, deaths per region, and quarantine status. This model had good fit (Chi2 (14) = 56.06, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI: 0.02, 0.05), CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.95), and the standardized coefficients are presented in Model 1 of Table 2. General and specific adherence were significantly associated (β = 0.17, p < 0.01). For general adherence, lower levels of conduct problems, being assigned female at birth, and having higher cognitive functioning during the initial testing period were all associated with higher levels of adherence. None of the variables, including conduct problems, were associated with specific adherence. Finally, the model fit was not significantly different when constrained across sex assigned at birth, suggesting no significant differences in the model according to this variable (Chi2 (14) = 12.81, n.s).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess if the differences in the associations observed between a specific predictor variable and the two types of adherence were statistically significantly different. For each predictor variable, the model was constrained to assess if model fit became significantly worse when the links between a respective predictor (i.e., conduct problems, sex assigned at birth, cognitive functioning) and the two outcomes variables (i.e., the two types of adherence) were constrained to be equal. No significant difference was observed for conduct problem status (Chi2 (1) = 0.11, n.s.) or sex assigned at birth (Chi2(1) = 0.00, n.s.) based on type of adherence. Significant differences were observed for cognitive functioning (Chi2(1) = 3.89, p < 0.05). This suggests that only higher cognitive functioning (but not sex assigned at birth or callous unemotional traits) were differentially associated with the adherence outcomes.

The Mediation Model

The second model, presented in model 2 of Table 2, tested how interactional (i.e., callous unemotional traits, impulsivity) and cumulative (i.e., student status, working outside the home, and problematic substance use) mechanisms mediated the associations between childhood conduct problems and later COVID-19 guideline adherence. Model fit was good (Chi2 (49) = 110.26, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI: 0.03, 05), CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.91), and again did not show significant sex differences (Chi2 (31) = 2.09, n.s). The associations between conduct problem status, the mediators, and general and specific COVID-19 guideline adherence are presented in model 2 of Table 2. Starting from the left and moving towards the right, conduct problems were associated with lower likelihood of being a student, higher levels of callous unemotional traits, higher levels of problematic substance use and higher levels of impulsivity. Focusing on general adherence, higher levels of conduct problems were no longer significantly associated with lower levels of adherence when the mediators were included in the model, but conduct problems were associated with multiple mediators. Lower levels of callous unemotional traits (along with being assigned female at birth and higher cognitive functioning) were associated with higher levels of general adherence. Significant indirect effects were observed between conduct problems and general adherence via callous unemotional traits (β = -0.07, p < 0.05, CI 95% -0.13, -0.003).

For specific adherence, lower callous unemotional traits and lower problematic substance use were both associated with higher specific adherence, as was being assigned female at birth. Significant indirect effects were only observed via callous unemotional traits (β = -0.08, p < 0.05, CI 95% -0.14, -0.01) and problematic substance use (β = -0.06, p < 0.05, CI 95% -0.10, -0.02). Follow up analyses indicated that the associations between substance use and the two different types of COVID-19 guideline adherence were significantly different (Chi2 (1) = 13.66, p < 0.01), suggesting that substance use was only significantly associated with lower specific but not general adherence. Finally, sensitivity tests indicated that the non-significant mediating role of impulsivity remained the same when subscale scores for attentional, motor and non-planning impulsivity were used as opposed to the total score (see Appendix Table 3).

Discussion

Understanding variation in COVID-19 guideline adherence among young adults offers unique insight into how childhood conduct problems shape health outcomes. Linking higher conduct problems with lower COVID-19 guideline adherence, and then identifying callous unemotional traits and substance use as being important mechanisms explaining this link, the current findings offer new insight into addressing guideline adherence. The finding that conduct problems were prospectively associated with COVID-19 guideline adherence supports a growing literature suggesting that both adolescent (i.e., Nivette et al., 2020) and concurrent antisocial behaviors (i.e., Miguel et al., 2021; O’Connell et al., 2020) were associated with lower levels of COVID-19 guideline adherence. Showing callous unemotional traits as mediating the link between conduct problems and both types of COVID-19 guideline adherence strengthens work linking antisocial-related traits with lower levels of COVID-19 guideline adherence among adults. Indeed, these longitudinal findings suggest that callous emotional traits precede (and are not a response to) COVID-19 restrictions. Findings further suggest the importance of including more detailed assessments of callous unemotional traits in future work examining COVID-19 guideline adherence (Miguel et al., 2021; Nivette et al., 2020; Nowak et al., 2020).

Including both general and specific adherence has ramifications for identifying mechanisms linked to different aspects of COVID-19 guideline adherence. We posit that general adherence may capture intentions regarding adherence, while specific adherence may align more closely to actual behaviors, as would be suggested by the unique explanatory role of substance use for specific but not general adherence. Indeed, problematic substance use is a predictor of instability during emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2005; Segrin & Bowers, 2019). We suggest that the significant difference in terms of how substance use was associated with adherence outcomes suggests that while substance use does not influence intentions towards following public health guidelines, the cumulating chaos caused by problematic substance use may impair day-to-day activities, including actual guideline adherence. This finding may also reflect, however, the use of a single item to assess general adherence, and points to the importance of employing a more detailed assessment of general adherence in future work.

Conduct problems were associated with a lower likelihood of being in school, but not with working outside the home during the pandemic, and neither of the SES-related cumulative factors were associated with COVID-19 guideline adherence. These findings may reflect our focus on early adulthood, where less differentiation in occupation by educational status is observed. Furthermore, while educational attainment has been previously associated with other forms of medical adherence, those studies very rarely account for cognitive functioning (as was done in this study) (DiMatteo, 2004b). Examining the consequences of conduct problems for different health outcomes, and across different parts of the life course, can inform understanding of how these problems are linked with morbidity and mortality.

Impulsivity, while linked with childhood conduct problems, did not account for the association between conduct problems and subsequent COVID-19 guideline adherence, as was the case when each subscale was examined separately. While some previous research has linked certain dimensions of impulsivity (i.e., non-planning) to medication adherence (Dunne et al., 2019), our findings align with previous work suggesting impulsivity is not associated with adherence (Bentzley et al., 2016). Impulsivity is also strongly associated with substance use (Verdejo-García et al., 2008), which may have accounted for the non-significant findings.

Finally women were generally more likely to report adherence to COVID-19 guidelines than men (Nivette et al., 2020). Gender differences were not observed in the association between conduct problem status and COVID-19 adherence, or in the factors that mediated this association, reflecting that not all previous research supports gender differences in the consequences of conduct problems (Wertz et al., 2018). Over sampling girls with conduct problems, moreover, permitted for a well-powered investigation of gender differences.

Limitations and future directions

While this study contains numerous strengths including oversampling children (and particularly girls) with conduct problems, and assessments of both general and specific COVID-19 guideline adherence, some limitations should be discussed. We relied on self-report for COVID-19 adherence. Future work including information drawn from wearable tracker devices, or for the presence of COVID-19 antibodies may supplement self-reported data. The current sample consisted entirely of individuals living in Quebec, Canada at the start of the pandemic, who were majority white and of French-Canadian origin. Adherence may be shaped by demographic and temporal factors not assessed here, and should be replicated in other populations at different periods during the pandemic. Finally, future work should address whether medical vulnerability of the individuals’ close contacts shapes adherence behaviors.

Despite these limitations, the current study suggests several directions for intervention and prevention. First, these findings underscore the importance of callous unemotional traits regarding COVID-19 guideline adherence. Currently, the strategies for dissimulating COVID-19 guideline adherence are developed for the population at large, and frequently appeal to concerns regarding the wellbeing of vulnerable members of society. While these broad approaches are important, addressing COVID-19 and future pandemics may require prevention practices that appeal to individuals for whom these messages are less compelling. Youth high in callous unemotional traits are less motivated by positive affiliated emotions and punitive practices than other youth (Viding & McCrory, 2019). Programs like “Let’s get Smart” have been used to reduce callous unemotional traits by addressing the benefits of paying attention to and considering the perceptions, needs, and feelings of others (Frederickson et al., 2013). Regarding COVID-19 guideline adherence, these insights suggest intervention approaches that focus on the self-serving benefits of COVID-19 guideline adherence, rather than punishing transgressions or emphasizing benefits to others. Second, these findings reflect how problematic substance use may interfere with COVID-19 guideline adherence and suggests the importance of providing additional support in guideline adherence for young adults with histories of problematic substance use. Ultimately, these findings underscore how a developmental psychopathology-informed approach can help to address an ongoing public health crisis, while also improving our understanding of the longitudinal health consequences of childhood conduct problems.

Data Availability

The data from the current project is currently held by the first author.

Code Availability

No custom software or code was used in this study.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. (2001). ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Allison, P.D. (2001). Missing data. London: Sage Publications.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2005). The Developmental Context of Substance use in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260503500202

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bégin, V., Déry, M., & Le Corff, Y. (2020). Developmental Associations between Psychopathic Traits and Childhood-Onset Conduct Problems. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 42(2), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-019-09779-2

Bentzley, J. P., Tomko, R. L., & Gray, K. M. (2016). Low pretreatment impulsivity and high medication adherence increase the odds of abstinence in a trial of N-Acetylcysteine in adolescents with cannabis use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 63, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.12.003

Bıçaksız, P., & Özkan, T. (2016). Impulsivity and driver behaviors, offences and accident involvement: A systematic review. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 38, 194–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2015.06.001

Bollen, K. A., & Stine, R. (1990). Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociological Methodology, 115–140.

Brown, M. T., & Bussell, J. K. (2011). Medication Adherence: WHO Cares? Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 86(4), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575

Caspi, A., Elder, G. H., & Bem, D. J. (1987). Moving against the world: Life-course patterns of explosive children. Developmental Psychology, 23(2), 308.

CDC 2020: Oster, A. M., Caruso, E., DeVies, J., Hartnett, K. P., & Boehmer, T. K. (2020). Transmission Dynamics by Age Group in COVID-19 Hotspot Counties — United States, April–September 2020. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 69, 1494–1496. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6941e1

Deshaies, C., Toupin, J., & Déry, M. (2009). Validation de l’échelle d’évaluation des traits antisociaux. [Validation of the rating scale of antisocial traits.]. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 41(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013565

DiMatteo, M. R. (2004a). Social Support and Patient Adherence to Medical Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychology, 23(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278

DiMatteo, M. R. (2004b). Variations in Patients’ Adherence to Medical Recommendations: A Quantitative Review of 50 Years of Research. Medical Care, 42(3), 200–209. JSTOR.

DiMatteo, M. R., Haskard, K. B., & Williams, S. L. (2007). Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis. Medical Care, 45(6), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318032937e

Dir, A. L., Coskunpinar, A., & Cyders, M. A. (2014). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between adolescent risky sexual behavior and impulsivity across gender, age, and race. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(7), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.004

Dunn, L. M., Dunn, L., & Theriault-Whalen, C. (1993). Échelle de vocabulaire en images peabody. Pearson Canada Assessment Inc.

Dunne, E. M., Cook, R. L., & Ennis, N. (2019). Non-planning impulsivity but not behavioral impulsivity is associated with HIV medication non-adherence. AIDS and Behavior, 23(5), 1297–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2278-z

Ebesutani, C., Bernstein, A., Nakamura, B. J., Chorpita, B. F., Higa-McMillan, C. K., & Weisz, J. R., & The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2010). Concurrent validity of the Child Behavior Checklist DSM-oriented scales: Correspondence with DSM diagnoses and comparison to syndrome scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(3), 373-384 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9174-9

Elder, G. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69(1), 1–12.

Erskine, H. E., Norman, R. E., Ferrari, A. J., Chan, G. C. K., Copeland, W. E., Whiteford, H. A., & Scott, J. G. (2016). Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(10), 841–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.016

Fanti, K. A., Colins, O. F., Andershed, H., & Sikki, M. (2017). Stability and change in callous-unemotional traits: Longitudinal associations with potential individual and contextual risk and protective factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000143

Fanti, K. A., Kyranides, M. N., Lordos, A., Colins, O. F., & Andershed, H. (2018). Unique and interactive associations of callous-unemotional traits, impulsivity and grandiosity with child and adolescent conduct disorder symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9655-9

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Ridder, E. M. (2005). Show me the child at seven: The consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(8), 837–849. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00387.x

Forsman, M., Lichtenstein, P., Andershed, H., & Larsson, H. (2010). A longitudinal twin study of the direction of effects between psychopathic personality and antisocial behaviour: Psychopathic personality and antisocial behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02141.x

Frederickson, N., Jones, A. P., Warren, L., Deakes, T., & Allen, G. (2013). Can developmental cognitive neuroscience inform intervention for social, emotional and behavioural difficulties (SEBD)? Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 18(2), 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.757097

Frick, P. J., & Hare, R. D. (2001). Antisocial process screening device: APSD: Multi-Health Systems Toronto.

Frick, Paul J., Ray, J. V., Thornton, L. C., & Kahn, R. E. (2014a). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 1–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033076

Frick, Paul J., Ray, J. V., Thornton, L. C., & Kahn, R. E. (2014b). Annual Research Review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous-unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(6), 532–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12152

Gadermann, A. M., Guhn, M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2012). Estimating ordinal reliability for Likert-type and ordinal item response data: A conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.7275/N560-J767

Germain, M., Guyon, L., Landry, A., Tremblay, J., Brunelle, N., & Bergeron, J. (2007). DEP-ADO Grille de dépistage de consommation problématique d’alcool et de drogues chez les adolescents et les adolescentes. Version 3.2. Recherche et intervention sur les substances psychoactives - Québec (RISQ). risqtoxico@uqtr.ca

Glasgow, A. M., Tynan, D., Schwartz, R., Hicks, J. M., Turek, J., Driscol, C., O’Donnell, R. M., & Getson, P. R. (1991). Alcohol and drug use in teenagers with diabetes mellitus. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197

Government of Québec (2013). Indicateurs de l'éducation-Édition 2011. Quebec, Canada: Ministry of Education Leisure and Sports.

Halfon, N., & Hochstein, M. (2002). Life Course Health Development: An Integrated Framework for Developing Health, Policy, and Research. The Milbank Quarterly, 80(3), 433–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00019

Hodapp, A. F., & Gerken, K. C. (1999). Correlations between Scores for Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—III and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—III. Psychological Reports, 84(3_suppl), 1139–1142. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3c.1139

Landry, M., Tremblay, J., Guyon, L., Bergeron, J., & Brunelle, N. (2004). La Grille de dépistage de la consommation problématique d’alcool et de drogues chez les adolescents et les adolescentes (DEP-ADO): Développement et qualités psychométriques. Drogues, santé et société, 3(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.7202/010517ar

Lapalme, M., Bégin, V., Le Corff, Y., & Déry, M. (2020). Comparison of Discriminant Validity Indices of Parent, Teacher, and Multi-Informant Reports of Behavioral Problems in Elementary Schoolers. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 42(1), 58-68.

Loeber, R., & Keenan, K. (1994). Interaction between conduct disorder and its comorbid conditions: Effects of age and gender. Clinical Psychology Review, 14(6), 497–523. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(94)90015-9

Longman, T., Hawes, D. J., & Kohlhoff, J. (2016). Callous-Unemotional Traits as Markers for Conduct Problem Severity in Early Childhood: A Meta-analysis. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47(2), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0564-9

MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. psyhref.

Maneiro, L., Gómez-Fraguela, J. A., Cutrín, O., & Romero, E. (2017). Impulsivity traits as correlates of antisocial behaviour in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.045

Miguel, F. K., Machado, G. M., Pianowski, G., de Carvalho, L., & F. . (2021). Compliance with containment measures to the COVID-19 pandemic over time: Do antisocial traits matter? Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110346

Molloy, G. J., O’Carroll, R. E., & Ferguson, E. (2014). Conscientiousness and medication adherence: a meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9524-4

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide, Eighth edition. Muthén & Muthén.

Niv, S., Tuvblad, C., Raine, A., Wang, P., & Baker, L. A. (2012). Heritability and Longitudinal Stability of Impulsivity in Adolescence. Behavior Genetics, 42(3), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-011-9518-6

Nivette, A., Ribeaud, D., Murray, A., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Hepp, U., Shanahan, L., & Eisner, M. (2020). Non-compliance with COVID-19-related public health measures among young adults in Switzerland: Insights from a longitudinal cohort study. Social Science & Medicine (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113370

Nowak, B., Brzóska, P., Piotrowski, J., Sedikides, C., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., & Jonason, P. K. (2020). Adaptive and maladaptive behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of Dark Triad traits, collective narcissism, and health beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110232

O’Connell, K., Berluti, K., Rhoads, S. A., & Marsh, A. (2020). Reduced social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with antisocial behaviors in an online United States sample [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ezypg

Odgers, C. L., Moffitt, T. E., Broadbent, J. M., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., …, & Caspi, A. (2008). Female and male antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 673–716. psyhref.

Olson, S. L., Schilling, E. M., & Bates, J. E. (1999). Measurement of impulsivity: construct coherence, longitudinal stability, and relationship with externalizing problems in middle childhood and adolescence. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 27(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021915615677

Parsons, J. T., Starks, T. J., Millar, B. M., Boonrai, K., & Marcotte, D. (2014). Patterns of substance use among HIV-positive adults over 50: Implications for treatment and medication adherence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 139, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.704

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(6), 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6%3c768::AID-JCLP2270510607%3e3.0.CO

Pedersen, W., Mastekaasa, A., & Wichstrøm, L. (2001). Conduct problems and early cannabis initiation: A longitudinal study of gender differences. Addiction, 96(3), 415–431. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9634156.x

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. psyhref.

van Prooijen, J.-W. (2017). Why Education Predicts Decreased Belief in Conspiracy Theories. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 31(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3301

Reef, J., Donker, A. G., Van Meurs, I., Verhulst, F. C., & Van Der Ende, J. (2011). Predicting adult violent delinquency: Gender differences regarding the role of childhood behaviour. European Journal of Criminology, 8(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811403444

Rivenbark, J. G., Odgers, C. L., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., Hogan, S., Houts, R. M., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2018). The high societal costs of childhood conduct problems: Evidence from administrative records up to age 38 in a longitudinal birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 59(6), 703–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12850

Sagatun, AAse, Heyerdahl, S., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Lien, L. (2015). Medical benefits in young adulthood: A population-based longitudinal study of health behaviour and mental health in adolescence and later receipt of medical benefits. BMJ Open, 5(5).

Segrin, C., & Bowers, J. (2019). Reciprocal effects of transitional instability, problem drinking, and drinking motives in emerging adulthood. Current Psychology, 38(2), 376–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9617-5

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Soveri, A., Karlsson, L. C., Antfolk, J., Lindfelt, M., & Lewandowsky, S. (2020). Unwillingness to engage in behaviors that protect against COVID-19: Conspiracy, trust, reactance, and endorsement of complementary and alternative medicine. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mhctf

Stanford, M. S., Mathias, C. W., Dougherty, D. M., Lake, S. L., Anderson, N. E., & Patton, J. H. (2009). Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(5), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.008

Stone, A. L., Becker, L. G., Huber, A. M., & Catalano, R. F. (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7), 747–775. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014

Swann, O. V., Holden, K. A., Turtle, L., Pollock, L., Fairfield, C. J., Drake, T. M., Seth, S., Egan, C., Hardwick, H. E., & Halpin, S. (2020). Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: Prospective multicentre observational cohort study. Bmj, 370.

Temcheff, C. E., Serbin, L. A., Martin-Storey, A., Stack, D. M., Ledingham, J., & Schwartzman, A. E. (2011). Predicting adult physical health outcomes from childhood aggression, social withdrawal and likeability: A 30-year prospective, longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18, 5–12. psyhref.

Thornton, L. C., Frick, P. J., Ray, J. V., Myers, T. D. W., Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (2019). Risky Sex, Drugs, Sensation Seeking, and Callous Unemotional Traits in Justice-Involved Male Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1399398

Valla, J. P., Breton, J. J., Bergeron, L., Gaudet, N., Berlhiaume, C., Saint-Georges, M., Daveluy, C., Tremblay, V., Lambert, J., & Houde, L. (1994). Quebec survey of mental health in youth aged 6 to 14 years. Hôpital Rivière-Des-Prairies.

Verdejo-García, A., Lawrence, A. J., & Clark, L. (2008). Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: Review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 777–810.

Viding, E., & McCrory, E. (2019). Towards understanding atypical social affiliation in psychopathy. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(5), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30049-5

Viding, E., & McCrory, E. J. (2012). Genetic and neurocognitive contributions to the development of psychopathy. Development and Psychopathology, 24(3), 969–983. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941200048X

Wan, W., & Balingit, M. (2020). WHO warns young people are emerging as main spreaders of the coronavirus. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/who-warns-young-people-are-emerging-as-main-spreaders-of-the-coronavirus/2020/08/18/1822ee92-e18f-11ea-b69b-64f7b0477ed4_story.html

Wertz, J., Agnew-Blais, J., Caspi, A., Danese, A., Fisher, H. L., Goldman-Mellor, S., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2018). From childhood conduct problems to poor functioning at age 18 years: examining explanations in a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(1), 54-60.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.437

Wiersinga, W. J., Rhodes, A., Cheng, A. C., Peacock, S. J., & Prescott, H. C. (2020). Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. Jama, 324(8), 782–793.

Wrzus, C., Hänel, M., Wagner, J., & Neyer, F. J. (2013). Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028601

Xie, K., Liang, B., Dulebenets, M. A., & Mei, Y. (2020). The Impact of Risk Perception on Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6256.

Zajenkowski, M., Jonason, P. K., Leniarska, M., & Kozakiewicz, Z. (2020). Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19?: Personality and perceptions of the COVID-19 situation. Personality and Individual Differences, 166, 110199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110199

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research under Grant [number FRN 82694]; The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada under Grant [SSHRC-37890]; by a Canada Research Chair awarded to the first author by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and by Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture under Grant [FRQSC-196505]. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of the funding agencies as well as France Girard, Mylène Villeneuve-Cyr, and the whole University of Sherbrooke Longitudinal Study team for their assistance in data collection, as well as the participants who provided their time to this project.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research under Grant [number FRN 82694]; The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada under Grant [SSHRC-37890]; by a Canada Research Chair awarded to the first author by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and by Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture under Grant [FRQSC-196505].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alexa Martin-Storey, Caroline Temcheff, Mélanie Lapalme and Michèle Déry designed the COVID-19 data collection, and Mélanie Lapalme and Michèle Déry supervised this data collection. Alexa Martin-Storey, Caroline Temcheff, Mélanie Lapalme, Michèle Déry and Jean-Pascal Lemelin contributed to the design of previous waves of data collection. Alexa Martin-Storey and Melina Tomasiello developed the database used for the current analyses. Alexa Martin-Storey, Melina Tomasiello and Audrey Mariamo drafted the initial version of the manuscript. Caroline Temcheff, Mélanie Lapalme, Michèle Déry and Jean-Pascal Lemelin subsequently edited multiple drafts of the manuscript. All authors have seen the final version of the manuscript and approve the submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All data collection associated with this project was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the institution of the first author.

Consent to Participant

During the initial testing period when participants were between ages of six and nine, parents provided informed consent, and children provided verbal assent to trained research assistants in person. At this time point, and at every subsequent time point research assistants explained that all participation was voluntary, and that participants could leave the study at any time. For the subsequent data collection periods in which the participants were adolescents, both parent and child informed consent were obtained by trained research assistants in person. During the final data collection period, when participants were in young adulthood, the participants provided informed consent to trained research assistants via telephone.

Consent for Publication

No information identifying a specific participant is available in the current manuscript. Furthermore, concerns over the identification of participants in our database have informed our policy regarding the non-publication of the associate data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin-Storey, A., Temcheff, C., Déry, M. et al. Conduct Problems and Adherence to COVID-19 Guidelines: A Developmental Psychopathology-Informed Approach. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 49, 1055–1067 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00807-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00807-y