Abstract

The theoretically well-grounded hypothesis that the availability of formal childcare has a positive impact on childbearing in the developed world has been part of the population literature for a long time. Whereas the participation of women in the labour force created a tension between work and family life, the increasing availability of formal childcare in many developed countries is assumed to reconcile these two life domains due to lower opportunity costs and compatible mother and worker roles. However, previous empirical studies on the association between childcare availability and fertility exhibit ambiguous results and considerable variation in the methods applied. This study assesses the childcare–fertility hypothesis for Belgium, a consistently top-ranked country concerning formal childcare coverage that also exhibits considerable variation within the country. Using detailed longitudinal census and register data for the 2000s combined with childcare coverage rates for 588 municipalities and allowing for the endogenous nature of formal childcare and selective migration, our findings indicate clear and substantial positive effects of local formal childcare provision on birth hazards, especially when considering the transition to parenthood. In addition, this article quantifies the impact of local formal childcare availability on fertility at the aggregate level and shows that in the context of low and lowest-low fertility levels in the developed world, the continued extension of formal childcare services can be a fruitful tool to stimulate childbearing among dual-earner couples.

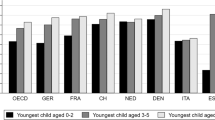

Source: K&G, ONE

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since 2000, the maximum deductible sum is 11.2 Euros per day per child (Van Lancker and Ghysels 2012).

For instance, in 2000 the minister for social welfare in the Flemish government sets the creation of 10 000 extra places in formal childcare as a policy goal (Kind and Gezin 2000–2003).

This age ceiling was extended to 6 years in 2005 and 12 years in 2009.

In Flanders, the share has decreased from 34.3 to 22.4% in 2002–2009 (Hedebouw and Peetermans 2009).

As it is possible that the lag between childcare availability and fertility decisions is larger, additional analyses (not shown) have been performed using 24 or 36 month time lags. These do not change the main results.

Results are not presented here, but available upon request.

References

Allison, P. (2009). Fixed effects regression models (quantitative applications in the social sciences). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Andersson, G., Duvander, A.-Z., & Hank, K. (2003). Do child care characteristics influence continued childbearing in Sweden? An investigation of the quantity, quality, and price dimension. In MPDIR working paper WP 2003-013.

Andersson, G., Duvander, A.-Z., & Hank, K. (2004). Do child-care characteristics influence continued child bearing in Sweden? An investigation of the quantity, quality, and price dimension. Journal of European Social Policy,14(4), 407–418.

Anxo, D., Fagan, C., Smith, M., Letablier, M.-T., & Perraudin, C. (2007). Parental leave in European companies. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Baizan, P. (2009). Regional child care availability and fertility decisions in Spain. Demographic Research,21(27), 803–842.

Beaujouan, E., Sobotka, T., & Brzozowska, Z. (2013). Education and sex differences in intended family size in Europe, 1990s and 2000s. Paper presented at the Changing families and fertility choices, Oslo, Norway.

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. London: Harvard University Press.

Blau, D. M. (2001). The child care problem: an econometric analysis. New York: Russel Sage.

Blau, D. M., & Robins, P. K. (1989). Fertility, employment, and childcare costs. Demography,26(2), 287–299.

Brewster, K. L., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2000). Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology,26, 271–296.

Castles, F. G. (2003). The world turned upside down: below replacement fertility, changing preferences and family-friendly public policy in 21 OECD countries. Journal of European Social Policy,13(3), 209–227.

De Henau, J., Meulders, D., & ODorchai, S. (2007). Making time for working parents: Comparing public childcare provision. In D. Del Boca & C. Wetzels (Eds.), Social policies, labour markets and motherhood. A comparative analysis of European countries (pp. 28–62). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Wachter, D., & Neels, K. (2011). Educational differentials in fertility intentions and outcomes: Family formation in Flanders in the early 1990s. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research,9, 227–258.

Deboosere, P., & Willaert, D. (2004). Codeboek algemene socio-economische enquête 2001. Working paper 2004-1. Steunpunt Demografie Vakgroep Sociaal Onderzoek (soco) Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Brussels.

Del Boca, D. (2002). The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics,15(3), 549–573.

Demeny, P. (2003). Population policy dilemmas in Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Population and Development Review,29, 1–28.

Dujardin, C., Fonder, M., & Lejeune, B. (2015). Does formal child care availability for 0–3 year olds boost mothers’ employment rate? Pandel data based evidence from Belgium. IWEPS working paper.

Fagnani, J. (2002). Why do French women have more children than German women? Family policies and attitudes towards child care outside the home. Community, Work & Family,5(1), 103–119.

Farfan-Portet, M.-I., Lorant, V., & Petrella, F. (2011). Access to childcare services: The role of demand and supply-side policies. Population Research and Policy Review,30, 165–183.

Felmlee, D. H. (1995). Causes and consequences of women’s employment discontinuity 1967–1973. Work and Occupations,22, 167–188.

Gauthier, A. H. (2007). The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: a review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review,26(3), 323–346.

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegard, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behaviour. Population and Development Review,41(2), 207–239.

Gornick, J., Meyers, M., & Ross, K. (1997). Supporting the employment of mothers: Policy variation across fourteen welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy,7(1), 45–70.

Gustafsson, S., & Stafford, F. P. (1992). Child care subsidies and labour supply in Sweden. Journal of Human Resources,27(1), 204–230.

Hank, K., & Kreyenfeld, M. (2003). A multilevel analysis of child care and women’s fertility decisions in Western Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family,65(3), 584–596.

Hedebouw, G., & Peetermans, A. (2009). Onderzoek naar het gebruik van opvang voor kinderen jonger dan 3 jaar in het Vlaamse Gewest in 2009: HIVA—K.U.Leuven, Steunpunt Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Gezin, Kind en Gezin.

Kil, T., Wood, J., & Neels, K. (2018). Parental leave uptake among migrant and native mothers: Can precarious employment trajectories account for the difference? Ethnicities,18(1), 106–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796817715292.

Kind & Gezin. (2000–2003). Jaarverslagen Kinderopvang 2000–2003. https://www.kindengezin.be/cijfers-en-rapporten/rapporten/over-kind-en-gezin/jaarverslagen/. Accessed 6 Dec 2018.

Klüsener, S., Neels, K., & Kreyenfeld, M. (2013). Family policies and the Western European fertility divide: Insights from a natural experiment in Belgium. Population and Development Review,39(4), 587–610.

Kravdal, O. (1996). How the local supply of day-care centers influences fertility in Norway: A parity-specific approach. Population Research and Policy Review,15, 201–218.

Kremer, M. (2006). The politics of ideals of care: Danish and Flemish child care policy compared. Social Politics,13(2), 261–285.

Lehrer, E. L., & Kawasaki, S. (1985). Child care arrangements and fertility: An analysis of two-earner households. Demography,22(4), 499–513.

Liefbroer, A. C., & Corijn, M. (1999). Who, what, where and when? Specifying the impact of educational attainment and labour force participation on family formation. European Journal of Population,15, 45–75.

Luci-Greulich, A., & Thévenon, O. (2013). The impact of family policies on fertility trends in developed countries. European Journal of Population / Revue européenne de Démographie, 29(4), 387–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9295-4.

Mason, K. O., & Kuhlthau, K. (1992). The perceived impact of child care costs on women’s labor supply and fertility. Demography,29(4), 523–543.

Matysiak, A., & Vignoli, D. (2008). Fertility and women’s employment: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Population,24, 363–384.

Matysiak, A., & Węziak-Białowolska, D. (2016). Country-specific conditions for work and family reconciliation: An attempt at quantification. European Journal of Population,32, 1–36.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review,26(3), 427–439.

Merla, L., & Deven, F. (2013). Belgium country note. In P. Moss (Ed.), International review of leave policies and research 2013.

Mills, M., Rindfuss, R. R., McDonald, P., & Te Velde, E. R. (2011). Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Human Reproduction Update,17(6), 848–860.

Morel, N. (2007). From subsidiarity to “free choice”: Child- and elderly-care policy reforms in France, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. Social Policy & Administration,41(6), 618–647.

Neels, K. (2006). Reproductive strategies in Belgian fertility, 1960–1990.

Neyer, G. (2003). Family policies and low fertility in Western Europe. In MPIDR working paper WP, WP 2003-021.

Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2008). Consequences of family policies on childbearing Behavior: Effects or artifacts? Population and Development Review,34(4), 699–724.

Ni Bhrolchain, M., & Beaujouan, E. (2012). Fertility postponement is largely due to rising educational enrolment. Population Studies,66(3), 311–327.

ONE. (2018). Office de la naissance et de l’enfance—Accueil petite enfance.

Plantenga, J., Scheele, A., Peeters, J., Rastrigina, O., Piscova, M., & Thévenon, O. (2013). Barcelona targets revisited. Brussels: European Parliament.

Population Council. (2006). Policies to reconcile labor force participation and childbearing in the European Union. Population and Development Review,32(2), 389–393.

Puur, A., Klesment, M., Rahnu, L., & Sakkeus, L. (2016). Educational gradient in transition to second birth in Europe: differences related to societal context. Paper presented at the European population conference (EAPS), Mainz, Germany.

Raz-Yurovich, L. (2014). A transaction cost approach to outsourcing by households. Population and Development Review,40(2), 293–309.

Rindfuss, R. R., & Brewster, K. L. (1996). Childrearing and fertility. Population and Development Review,22, 258–289.

Rindfuss, R. R., Guilkey, D. K., Morgan, S. P., & Kravdal, O. (2010). Child-care availability and fertility in Norway. Population and Development Review,36(4), 725–748.

Rindfuss, R. R., Guilkey, D. K., Morgan, S. P., Kravdal, O., & Guzzo, K. B. (2007). Child care availability and first-birth timing in Norway. Demography,44, 345–372.

Ruokolainen, A., & Notkola, I.-L. (2002). Familial, situational and attitudinal determinants of third-birth intentions and their uncertainty. Yearbook of Population Research in Finland,38, 179–206.

Shapiro, D., & Mott, F. L. (1994). Long-term employment and earnings of women in relation to employment behavior surrounding the first birth. Journal of Human Resources,29, 248–276.

Sjöberg, O. (2004). The role of family policy institutions in explaining gender-role attitudes: A comparative multilevel analysis of thirteen industrialized countries. Journal of European Social Policy,14, 107–123.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review,37(2), 267–306.

Thevenon, O. (2008). Family policies in Europe: available databases and initial comparisons. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research,2008, 165–177.

Thevenon, O. (2011). Does fertility respond to work and family-life reconciliation policies in France? In N. Takayama & M. Werding (Eds.), Fertility and public policy: How to reverse the trend of declining birth rates. Cambridge, London: MIT Press.

Thomese, F., & Liefbroer, A. (2013). Child care and child births: The role of grandparents in the Netherlands. Journal of Marriage and Family,75(2), 403–421.

Van Bavel, B., & Rozanska-Putek, J. (2010). Second birth rates across Europe: Interactions between women’s level of education and child care enrolment. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research,8, 107–138.

Van de Kaa, D., & Lesthaeghe, R. (1986). Bevolking, groei en krimp. Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Loghum Slaterus.

Van Lancker, W., & Ghysels, J. (2012). Who benefits? The social distribution of subsidized childcare in Sweden and Flanders. Acta Sociologica,55(2), 125–142.

Vande Gaer, E., Gijselinckx, C., & Hedebouw, G. (2013). Het gebruik van opvang voor kinderen jonger dan 3 jaar in het Vlaamse Gewest. Leuven.

Vandelannoote, D., Vanleenhove, P., Decoster, A., Ghysels, J., & Verbist, G. (2013). Maternal employment: The impact of triple rationing in childcare in Flanders. KULeuven Center for Economic Studies: discussion paper series DPS13.07.

Vandenbroeck, M. (2006). Globalisation and privatisation: The impact on childcare policy and practice. Working papers, 38, The Hague, The Netherlands: Bernard van Leer Foundation.

Wood, J., & Neels, K. (2017). First a job, then a child? Subgroup variation in women’s employment-fertility link. Advances in Life Course Research,33, 38–52.

Wood, J., Neels, K., & Kil, T. (2014). The educational gradient of childlessness and cohort parity progression in 14 low fertility countries. Demographic Research,31(46), 1365–1416.

Wood, J., Neels, K., Marynissen, L., & Kil, T. (2017). Differences de genre dans la participation au marche de l’emploi apres la constitution de famille. Impact des caracteristiques initiales du travail sur la sortie et la prise du conge parental dans les menages a deux revenus. Revue Belge de Sécurité Sociale,2(5), 173–208.

Wood, J., Neels, K., & Vergauwen, J. (2016). Economic and Institutional context and second births in seven European countries. Population Research and Policy Review,35(3), 305–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9389-x.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (Grant No. G.0327.15 N) and the Research Council of the University of Antwerp (Grant BOFNOI-20102014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This research does not involve human participants and/or animals.

Informed Consent

This article is submitted under informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wood, J., Neels, K. Local Childcare Availability and Dual-Earner Fertility: Variation in Childcare Coverage and Birth Hazards Over Place and Time. Eur J Population 35, 913–937 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9510-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9510-4