Abstract

Using West German panel data constructed from the 1988 and 1994/1995 wave of the DJI Familiensurvey, we analyze the stability and determinants of individuals’ total desired fertility. We find considerable variation of total desired fertility across respondents and across interviews. In particular, up to 50% of individuals report a different total desired fertility across survey waves. Multivariate analysis confirms the importance of background factors including growing up with both parents, having more siblings, and being Catholic for preference formation. Consistent with the idea that life course experiences provide new information regarding the expected costs and benefits of different family sizes, the influence of background factors on total desired fertility is strong early in life and weakens as subsequent life course experiences, including childbearing, take effect. Accounting for unobserved individual heterogeneity, we estimate that an additional child may increase the total desired fertility of women with children by 0.14 children, less than what conventional estimates from cross-sectional data would have suggested.

Résumé

Sur la base du panel de données d’Allemagne de l’Ouest constitué à partir des vagues de 1988 et 1994/95 de l’Enquête Famille “DJI Familiensurvey”, nous analysons la stabilité et les déterminants de la fécondité totale désirée par les individus. Une variation considérable de la fécondité totale désirée apparaît entre individus et entre interviews. En particulier, jusqu’à 50% des individus déclarent une fécondité totale désirée différente d’une vague d’enquête à l’autre. L’analyse multivariée confirme l’importance des facteurs de contexte pour la formation des préférences en la matière, y compris le fait d’avoir grandi avec ses deux parents, d’avoir plus de frères et soeurs ou d’être de religion Catholique. En accord avec l’idée que les expériences vécues apportent des informations nouvelles par rapport au coûts et bénéfices de différentes tailles de famille, l’influence des facteurs de contexte sur la fécondité totale désirée est forte au début de la vie, et s’affaiblit au fur et à mesure des expériences, y compris de la procréation. En prenant en compte l’hétérogénéité individuelle non observée, nous estimons qu’un enfant de plus pourrait élever la fécondité totale désirée par les femmes ayant déjà des enfants de 0.14 enfant, un résultat en deçà de ce que laisseraient supposer les estimations conventionnelles basées sur des données transversales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

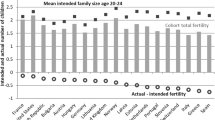

Among West German women, for example, completed cohort fertility has fallen from 2.2 to 1.6 children per women between the 1935 and the 1956 birth cohorts, while the corresponding desired number of children is estimated to have declined from 2.5 to 2.2 (see Heiland et al. 2005, Fig. 1). Other studies report on the trends for specific countries or regions (e.g., Toulemon 1996, 2001 for France).

The predictive value of preference data has been controversially debated for at least four decades (see Blake 1966; Westoff and Ryder 1977; Westoff 1981; and Long and Wetrogan 1981 for early critiques based on U.S. data and Van Hoorn and Keilman 1997 and Hagewen and Morgan 2005 for recent surveys of this literature).

Notable exceptions are Freedman et al. (1965), Gisser et al. (1985), Miller and Pasta (1995), and Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan (2003). Freedman et al. (1965) study the characteristics associated with revisions in expected family size during the first two years of marriage among a sample of couples in the Detroit area interviewed annually between 1961 and 1963. Gisser et al. examined fertility preferences of married women in Austria interviewed in 1978 and 1981/82. Miller and Pasta study the determinants of fertility motivations and preferences in a small sample of married individuals from the San Francisco Bay Area. Unlike the present article, Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan do not focus on the determinants of fertility preferences but study the gap between birth intentions and subsequent fertility outcomes.

We note that attained fertility and wanted fertility could diverge if there are significant social influences that are reflected in attained fertility but not in wanted fertility. As discussed in Bongaarts (1990), actual and wanted fertility can also differ due to biological forces, chance, or competing objectives. Recent evidence from European populations shows that achieved family size falls short of the desired one rather than the other way around (Heiland et al. 2005; Noack and Østby 2002; Van Peer 2002; Symeonidou 2000; Van Hoorn and Keilman 1997).

To what extent individuals, on average, correctly anticipate the benefits and costs of having (a particular number of) children is unclear. Udry (1983), for example, argues that fertility plans are updated at each parity. Evidence from individuals’ retirement behavior, for example, suggests that individuals are able to formulate very accurate expectations regarding the timing of their retirement (Benítez-Silva and Dwyer 2005).

The Familiensurvey does not collect data on spousal family size preferences. While we do not limit our sample to individuals with partners, it would be interesting to control for spousal preferences given evidence that they have an independent effect on fertility preferences and actual fertility (e.g., Morgan 1985; Thomson et al. 1990; Thomson 1997; Van Peer 2002; Voas 2003). However, we do not expect this to be a major limitation for those respondents with partners since the instrument of wanted fertility that we use explicitly asks that individuals answer for themselves as discussed below in more detail.

Models that allow for non-linear effects have been used in a cross-sectional context (see e.g., Philipov et al. 2004 and Heiland et al. 2005) but these papers do not provide strong evidence against a linear specification. The advantage of our statistical approach over alternative strategies allowing for non-linearities is its ability to account for person-specific unobserved heterogeneity that may be correlated with the time-varying variables as discussed below.

The limitations of this estimation strategy are well-known. In particular, fixed-effects estimates may be considered inefficient as they do not utilize the variation across individuals. This also implies that the effect of time-invariant individual characteristics cannot be identified. For a more detailed discussion of the assumptions of fixed effect panel models see Wooldridge (2002).

Data from the most recent wave of the DJI Familiensurvey (2000) are not used in this study since the survey instrument on desired number of children does not compare to the earlier waves.

Since individuals living in East Germany were not sampled until after the reunification (they were sampled in 1994/95), the panel starting in 1988 does not contain respondents from East Germany. For details on the sample construction and the comparisons to census data see Bender et al. (1996).

Coombs (1974) introduced a scale of family size preference capturing a person’s first, second and third preference using a series of questions on the most-preferred, second-most-preferred, etc. number of children. Unfortunately, the present data do not permit construction of Coombs’ scale.

For further detail regarding the construction of the measure see Heiland et al. (2005).

Morgan (1981 1982) suggests that respondents who answer “don’t know” to questions relating to fertility intentions are an important group that should not be discarded. Unfortunately, in the DJI Familiensurvey a distinction between “don’t know” and missing for other reasons cannot be made. Hence, we do not include this group in our analysis.

Comparison with a similar measure in the 2001 Eurobarometer (EUROSTAT 2001) for West Germany suggests that this cut-off affects only about 1% of the respondents. The maximum number of children reported there is seven.

Studies have employed different instruments of fertility preferences but desired, intended, wanted, or ideal number of children, which are similar to the one used here, are most common. Ryder and Westoff (1969) compare responses to questions on desired, intended, and expected number of children among American women and find insignificant differences between intended and expected number of children and only slightly higher desired numbers of children. Freedman et al. (1959) find higher desired than expected fertility among West German adults in 1958, but their question on desired fertility is qualified by if financial and other conditions of life were very good, which suggests a more hypothetical situation where having children is less costly.

We emphasize that information from older respondents is of interest since it may provide an important contrast to test hypotheses about stability and the determinants of preferred family size. Specifically, individuals may be able to better assess the net benefits of a particular family arrangement later in life, especially if they have children. Hence, we expect their preferred number of children to be more stable.

We constructed five binary indicators to measure different levels of completed education at the time of the interview: (1) no high school degree, (2) lowest or middle track high school degree (‘Volks-/Hauptschule’ or ‘Realschule’), (3) lowest or middle track high school degree with job training/apprenticeship (‘Lehre’, ‘Berufsfachschule’, ‘Volontariat’, ‘Laufbahnprüfung’, or equivalent), (4) college preparatory (college track) high school degree (‘Fachhochschulreife’ or ‘Hochschulreife’) with or without training, and (5) college degree or higher (‘Fachhochschule’, ‘Universität’ or equivalent). The ranking is based on the level of general schooling (basic secondary=ISCED2A, upper secondary=ISCED3A, tertiary/college=ISCED5A/5B/6) differentiated by additional vocational or job training programs. The ISCED codes stand for the education attained according to the International Standard Classification of Education. A helpful summary chart of the German education system can be found on the web at http://www.ed.gov/pubs/GermanCaseStudy/chapter1a.html.

The Inglehart scale measures a person’s post-materialism by how he or she ranks two post-materialistic societal objectives (‘giving the people more say in important government decisions’ and ‘protecting freedom of speech’) relative to two materialistic objectives (‘maintaining the order of nation’ and ‘fighting inflation’). A strong priority for post-materialistic goals is expressed by individuals who select the two post-materialistic objectives first (‘PPM’). A strong materialistic view is expressed by ranking the two materialistic goals first (‘MMP’). Other combinations express different degrees of post-materialism that lie between these extremes.

Gisser et al. (1985, p. 51) find that upward revisions are more common than downward revisions among married Austrian women.

Gender roles are progressing only slowly in West Germany (e.g., Stöbel-Richter and Brähler 2005) and combining family and career is difficult for women here given these inflexible labor markets, traditional gender roles, and social policies that favor the male breadwinner and female homemaker arrangement (see Kreyenfeld 2002; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Chesnais 1996; Gauthier 1996).

Due to space limitations, we do not report the estimates for other age groups or men. We also note that the coefficients for some variables (regional dummies and post-materialistic views) included in the models are not reported here. The additional results are available upon request.

Given evidence of greater stability among those initially reporting two as desired, the preference data may be heteroskedastic as discussed above. To address this issue, we also calculated the robust standard errors for the FE estimates. The results did not change the inference presented here.

References

Adsera, A. (2005). Differences in desired and actual fertility: An economic analysis of the Spanish case, IZA Discussion Paper No. 1584: http://ftp.iza.org/dp1584.pdf.

Astone, N. M., Nathanson, C. A., Schoen, R., & Kim, Y. J. (1999). Family demography, social theory, and investment in social capital. Population and Development Review, 25, 1–31.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries. NBER Conference Series (Vol. 11, pp 209–231). Princeton, NJ: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 279–288.

Bender, D., Bien, W., & Bayer, H. (1996). Wandel und Entwicklung familialer Lebensformen: Datenstruktur des DJI-Familiensurvey. München (unpublished manuscript).

Blake, J. (1966). Ideal family size among White Americans: A quarter of a century’s evidence. Demography, 11, 25–44.

Benítez-Silva, H., & Dwyer, D. S. (2005). The rationality of retirement expectations and the role of new information. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87, 587–592.

Bongaarts, J. (1990). The measurement of wanted fertility. Population and Development Review, 16, 487–506.

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. In R. A. Bulatao, & J. B. Casterline (Eds.), Global fertility transition. New York, NY: Population Council.

Brewster, K. L., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2000). Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 271–296.

Caldwell, J. C. (1982). Theory of fertility decline. London: Academic Press.

Calhoun, C., & de Beer, J. (1991). Birth expectations and fertility forecasts: The case of the Netherlands. In W. Lutz (Ed.), Future demographic trends in Europe and North America: What can we assume today? London: Academic Press.

Chesnais, J.-C. (1996). Fertility, family and social policy. Population and Development Review, 22, 729–739.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94(Supplement), S95–S120.

Coombs, L. C. (1974). The measurement of family size preferences and subsequent fertility. Demography, 11, 587–611.

Coombs, L. C. (1979). Reproductive goals and achieved fertility: A fifteen-year perspective. Demography, 16, 523–534.

DJI Familiensurvey (various years). Wandel und Entwicklung familialer Lebensformen, Welle, various. Deutsches Jugendinstitut, DJI. München.

Duncan, O. D., Freedman, R., Coble, J. M., & Slesinger, D. (1965). Marital fertility and family size of orientation. Demography, 2, 508–515.

Easterlin, R. A. (1978). The economics and sociology of fertility: A synthesis. In C. Tilly (Eds.), Historical Studies of Changing Fertility (pp. 57–133). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Engelhardt, H. (2004). Fertility intentions and preferences: Effects of structural and financial incentives and constraints in Austria, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Paper No. 02/2004: http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/download/WP2004_2.pdf.

EUROSTAT (2001). Europäische Sozialstatistik Bevölkerung. Luxembourg: European Communities.

Friedman, D., Hechter, M., & Kanazawa, S. (1994). A theory of the value of children. Demography, 31, 375–401.

Frejka, T., & Calot, G. (2001). Cohort reproductive patterns in low-fertility countries. Population and Development Review, 27, 103–132.

Freedman, R., Baumert, G., & Bolte, M. (1959). Expected family size and family size values in West Germany. Population Studies, 13, 136–150.

Freedman, R., Coombs, L. C., & Bumpass, L. (1965). Stability and change in expectations about family size: A longitudinal study. Demography, 2, 250–275.

Freedman, R., Freedman, D. S., & Thornton, A. D. (1980). Changes in fertility expectations and preferences between 1962 and 1977: Their relation to final parity. Demography, 17, 1–11.

Gauthier, A. H. (1996). The state and the family. A comparative analysis of family policies in industrialized countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gisser, R., Lutz, W., & Münz, R. (1985). Kinderwunsch und Kinderzahl. In R. Münz (Eds.), Leben mit Kindern. Wunsch und Wirklichkeit (pp. 33–94). Wien: Franz Deuticke.

Goldstein, J., Lutz, W., & Testa, M. R. (2003). The emergence of sub-replacement family size ideals in Europe. Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 479–496 (Special Issue on Very Low Fertility).

Gustavus, S. O., & Nam, C. B. (1970). The formation and stability of ideal family size among young people. Demography, 7, 43–51.

Hausman, J. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271.

Hagewen, K., & Morgan, P. S. (2005). Intended and ideal family size in the United States, 1970–2002. Population and Development Review, 31, 507–527.

Heiland, F. & Prskawetz, A. (2004). Female life cycle fertility, demand for higher education and desired family size in post-transitional societies: Theory and evidence from West Germany, Paper presented at the Economic Demography Workshop, Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Boston, USA.

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A. & Sanderson, W. C. (2005). Do the more-educated prefer smaller families? Vienna Institute of Demography Working Paper No. 03/2005: http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/download/WP2005_3.pdf.

Hendershot, G. E. (1969). Familial satisfaction, birth order, and fertility values. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 31, 27–33.

Hendershot, G. E., & Placek, P. J. (1981). Predicting fertility, demographic studies of birth expectations. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Hirsch, M. B., Seltzer, J. R., & Zelnik, M. (1981). Desired family size of young American women, 1971 and 1976. In G. E. Hendershot, & P. J. Placek (Eds.), Predicting Fertility (pp. 207–234). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Hoffman, L. W., & Manis, J. D. (1979). The value of children in the United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 583–596.

Huestis, R. R., & Maxwell, A. (1932). Does family size run in families?. The Journal of Heredity, 21, 77–79.

Huinink, J. (1995). Warum noch Familie? Zur Attraktivität von Partnerschaft und Elternschaft in unserer Gesellschaft. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

Huinink, J. (2001). The Macro-micro-link in demography – explanations of demographic change, Paper presented at the Conference “The second demographic transition in Europe”, 23–28 June 2001, Bad Herrenalb, Germany: http://www.demogr.mpg.de/Papers/workshops/010623 paper08.pdf.

Joyce, T., Kaestner, R., & Korenman, S. (2002). Retrospective assessments of pregnancy intentions. Demography, 39, 199–213.

Kantner, J. F., & Potter, R. G. Jr. (1954). The relationship of family size in two successive generations. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 32, 294–311.

Kohler, H.-P. (2001). Fertility and social interactions: An economic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kohler, H. P., Rodgers, J. L., & Christensen, K. (1999). Is fertility behavior in our genes? Findings from a Danish twin study. Population and Development Review, 25, 253–288.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2001). Employment and fertility – East Germany in the 1990s. Dissertation, Rostock University.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2002). Time squeeze, partner effect or self-selection? An investigation into the positive effect of womens’ education on second birth risks in West Germany. Demographic Research, 7, 15–48.

Löhr, C. (1991). Kinderwunsch und Kinderzahl. In H. Bertram (Ed.), Die Familie in Westdeutschland, Stabilität und Wandel familialer Lebensformen Deutsches Jugendinstitut, Familien-Survey (Vol. 1, 461–496), Opladen: Leske Budrich.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. 1988. Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14, 1–45.

Livi Bacci, M. (2001). Comment: Desired family size and the future course of fertility. Population and Development Review, 27, 282–289 (Supplement, “Global fertility transition”).

Long, J. F., & Wetrogan, S. I. (1981). The utility of birth expectations in population projections. In G. E. Hendershot, & P. J. Placek (Eds.), Predicting fertility (pp. 29–50). Lexington: Lexington Books.

Lutz, W. (1996). Future reproductive behavior in industrialized countries. In W. Lutz (Ed.), The future population of the world: What can we assume today? London: Earthscan Publications.

McAllister, P., Stokes, C. S., & Knapp, M. (1974). Size of family of orientation, birth order, and fertility values: A reexamination. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 36, 337–342.

McCallum, B. T. (1972). Relative asymptotic bias from errors of omission and measurement. Econometrica, 40, 757–758.

McCleland, G. H. (1983). Family size desires as measures of demand. In R. A. Bulatao, & R. Lee (Eds.), Determinants of fertility in developing countries (Vol. 1). New York: Academic Press.

Menniti, A. (2001). Fertility intentions and subsequent behavior: first results of a panel study, Paper presented at the European Population Conference, Helsinki, June 7–9.

Miller, W. B., & Pasta, D. J. (1995). How does childbearing affect fertility motivations and desires? Social Biology, 42, 185–198.

Miller, W. B., Pasta, D. J., MacMurray, J., Chiu, C., Wu, S., & Comings, D. E. (1999). Genetic influences on childbearing motivation and parental satisfaction: A theoretical framework and some empirical evidence. In L. Severy, & W. B. Miller (Eds.), Advances in population: Psychological perspectives (Vol. III). London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

Monnier, A. (1987). Projects de fécondité et fécondité effective. Une enquête longitudinal: 1974, 1976, 1979. Population, 6, 819–842.

Morgan, P. S. (1981). Intention and uncertainty at later stages of childbearing: the United States 1965 to 1970. Demography, 18, 267–285.

Morgan, P. S. (1982). Parity-specific fertility intentions and uncertainty: the United States, 1970 to 1976. Demography, 19, 215–334.

Morgan, P. S. (1985). Individual and couple intentions for more children: A research note. Demography, 22, 125–132.

Morgan, P. S., & Chen, R. (1992). Predicting childlessness for recent cohorts of American women. International Journal of Forecasting, 8, 477–493.

Noack, T., & Østby, L. (2002). Free to choose – but unable to stick to it? Norwegian fertility expectations and subsequent behaviour in the following 20 years. In M. Macura, G. Beets (Eds.), Dynamics of fertility and partnership in Europe: Insights and lessons from comparative research (Vol. 1). New York and Geneva, United Nations.

Philipov, D., Spéder, Z. & Billari, F. C. (2004). Fertility intentions in a time of massive societal transformation: theory and evidence from Bulgaria and Hungary, Paper presented at the 2004 Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America, Boston, March 31–April 3.

Preston, S. H. (1987). Changing values and falling birth rates. In K. Davis, M. S. Bernstam, & R. Ricardo-Campbell (Eds.), Below replacement fertility in industrialized societies: causes, consequences, policies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Quesnel-Vallée, A. & Morgan, S. P. (2003). Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the U.S.Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 497–525 (Special Issue on Very Low Fertility).

Rindfuss, R. R., Morgan, S. P., & Swicegood, G. (1988). First births in America: changes in the timing of parenthood. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ryder, N. B., & Westoff, C. F. (1969). Relationships among intended, expected, desired and ideal family size: United States, 1965. Washington: U.S. Center for Population Research.

Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, J. Y., Nathanson, C. A., & Fields, J. M. (1999). Do fertility intentions affect fertility behavior? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 790–799.

Schoen, R., Kim, Y. J., Nathanson, C. A., Fields, J., & Astone, N. M. (1997). Why do Americans want children? Population and Development Review, 23, 333–358.

Stöbel-Richter, Y., & Brähler, E. (2005). Einstellungen zur Vereinbarkeit von Familie und weiblicher Berufstätigkeit und Schwangerschaftsabbruch in den neuen und alten Bundesländern. Zeitschrift für Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 65, 256–265.

Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1977). Age, fertility expectations and plans for employment. American Sociological Review, 42, 769–783.

Symeonidou, H. (2000). Expected and actual family size in Greece. European Journal of Population, 16, 335–352.

Testa, M. R. & Grilli, L., 2006, The influence of childbearing regional contexts on ideal family size in Europe. Population, 61, 99–127 (English Edition).

Thomson, E. (1997). Couple childbearing desires, intentions, and births. Demography, 34, 343–354.

Thomson, E., McDonald, E., & Bumpass, L. L. (1990). Fertility desires and fertility: Hers, his, and theirs. Demography, 27, 579–588.

Thornton, A. D., Freedman, R., & Freedman, D. S. (1984). Further reflections on changes in fertility expectations and preferences. Demography, 21, 423–429.

Toulemon, L. (1996). Very few couples remain voluntarily childless. Population, 8, 1–27 (English Edition).

Toulemon, L. (2001). Why fertility is not so low in France, Paper presented at the Conference on International Perspectives on Low Fertility: Trends, Theories and Policies, Tokyo, 21–23 March 2001.

Udry, J. R. (1983) Do couples make fertility plans one birth at a time?. Demography, 20, 117–128.

Udry, J. R. (1996). Biosocial models of low-fertility societies. Population and Development Review, 22, 325–336 (Supplement, “Fertility in the United States: New Patterns, New Theories”).

Van de kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42, 1–57.

Van de Kaa, D. J. (2001). Postmodern fertility preferences: from changing value orientation to new behavior. Population and Development Review, 27, 290–331 (Supplement, “Global fertility transition”).

Van Hoorn, W. & Keilman, N. (1997). Births expectations and their use in fertility forecasting, EUROSTAT Working Paper E4/1997–4: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-AP-01-025/DE/KS-AP-01-025-DE.PDF.

Van Peer, C. (2002). Desired and realized fertility in selected FFS-countries. In M. Macura, & G. Beets (Eds.), Dynamics of fertility and partnership in Europe: Insights and lessons from comparative research (Vol. 1, pp. 117–142). New York and Geneva, United Nations.

Voas, D. (2003). Conflicting preferences: a reason fertility tends to be too high or too low. Population and Development Review, 29, 627–652.

Westoff, C. F. (1981). The validity of birth intentions: evidence from U.S. longitudinal studies. In G. E. Hendershot, & P. J. Placek (Eds.), Predicting fertility (pp. 51–60). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Westoff, C. F., & Ryder, N. B. (1977). The predictive validity of reproductive intentions. Demography, 14, 431–453.

Willis, R. (1973). A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 514–564.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to two anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank participants of the session on Mismatches between Fertility Intentions and Behavior: Causes and Consequences at the 2007 Meetings of the Population Association of America and seminar participants at the Vienna Institute of Demography. This research was (partly) financed by the European Commission under the RTN Grant project No. HPRNCT-000234-2002. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. Heiland is indebted to the Vienna Institute of Demography for their hospitality while parts of this project were in progress.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A. & Sanderson, W.C. Are Individuals’ Desired Family Sizes Stable? Evidence from West German Panel Data. Eur J Population 24, 129–156 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-008-9162-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-008-9162-x