Abstract

In this paper we present a stylised framework of fiscal policy determination that considers both structural targets and cyclical factors. We find significant cyclical asymmetry in the behaviour of fiscal variables in a sample of fourteen EU countries over 1970–2007, with budgetary balances (both overall and primary) deteriorating in contractions without correspondingly improving in expansions. Analysis of budget components reveals that cyclical asymmetry comes from expenditure. We find no evidence that fiscal rules introduced in 1992 with the Treaty of Maastricht affected the cyclical behaviour of fiscal variables. Numerical simulations show that cyclical asymmetry inflated average deficit levels, contributing significantly to debt accumulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

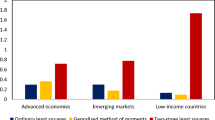

The cyclical conditions are usually summarised by the output gap (ω), i.e. the percentage difference between actual output (y) and its trend (or potential) value (y*): ω = (y − y*)/y*. Cyclical conditions are favourable when the output gap is positive (i.e. when output is above trend), unfavourable when the output gap is negative. The automatic reaction of the budget to the output gap is usually measured by the so-called “budget sensitivity” (ε), i.e. the change in the deficit-to-GDP ratio (b) corresponding to a one per cent change in output: ε = Δb/(Δy/y). Since the output (automatic) elasticities of revenue and expenditure (η R ,η G defined as η X = (ΔX/X)/(Δy/y)) are often close to, respectively, one and zero (see, e.g., Bouthevillain et al. 2001), budget sensitivity largely depends on the size of government as measured by the expenditure-to-GDP ratio (ε = η R R/Y − η G G/Y + b; see, e.g., Kumar and Ter-Minassian 2007; estimates of ε for EU countries are often close to 0.5; see, e.g. Bouthevillain et al. 2001).

The estimated overall reaction of the budget (as opposed to the automatic sensitivity discussed in footnote 1 above) is 0.4 for negative output gaps and zero for positive ones.

Kumar and Ter-Minassian (2007) report regression results indicating an asymmetric reaction of the expenditure-to-GDP ratio to positive and negative output gaps.

These can be thought of as the result of the optimisation of an objective function linking electoral support—or consistency with one’s “ideology”, or both—to a number of macroeconomic variables, subject to constraints defined by one’s preferred model of the economy (along the lines of the literature on the political business cycle; see, e.g., Nordhaus 1975; Alesina 1987). Alternatively, b* and d* may be seen as the government’s preferred solution to the present value budget constraint (Blanchard et al. 1990). Artis and Marcellino (1998) provide a review of studies testing the hypothesis that governments actually behave so as to satisfy the present value budget constraint. Finally, a debt stabilisation motive in modelling budgetary decisions has been adopted in empirical analyses by several authors defining “simple” fiscal rules in analogy to the Taylor rule for monetary policy (see, e.g., Bohn 1998; Ballabriga and Martinez-Mongay 2002; Galì and Perotti 2003).

If Eq. 2 were specified in cyclically-adjusted terms, the right hand side of Eq. 4 would include additional terms featuring lagged positive and negative output gaps. However, when we tested this specification we did not find lagged output gaps to be significant. It should also be noted that a different form of Eq. 4 is often used in the literature, where the cyclically-adjusted balance is regressed against its lagged value, the lagged value of debt and the output gap (plus, possibly, other control variables; see, e.g., Golinelli and Momigliano 2008 and the references therein):

$$ cab_{t} = \xi_{0} + \xi_{1} cab_{t - 1} + \xi_{2} d_{t - 1} + \xi_{3} \omega_{t} \, $$(a)Neither 4 in the main text, nor (a) above have micro-foundations. Thus, when choosing between the two models one can only rely on how they fit the data. From 4, using the identity b t = cab t + εω t (where the budget balance is split into its cyclically-adjusted component—cab t —and the automatic reaction to the output gap—εω t ) and dropping the distinction between positive and negative output gaps to economize in notation, we get:

$$ cab_{t} = \alpha_{0} + \alpha_{1} cab_{t - 1} + \alpha^{\prime}_{1} \omega_{t - 1} + \alpha_{2} d_{t - 1} + (\mu - \varepsilon )\omega_{t} \, $$(b)Where α 0 = αb* + βd*; α 1 = 1−α, and α′1 = α 1 ε. Comparison of (a) and (b) shows that the two specifications are equivalent if: (1) α′1 = 0 (that is, if current policy, as measured by cab t , is not affected by past cyclical conditions); or (2) if the output gap is so persistent that it can be safely assumed that ω t = ω t−1. With our sample, in regressions not reported here, we consistently find α′1 ≠ 0. Moreover, the correlation coefficient between ω t and ω t−1 is about 0.5. Hence, we retain 4 as our preferred specification.

Otherwise we would be assuming perfect forecast on the part of the government, which is clearly too restrictive an assumption. When the purpose of the analysis is the assessment of policy intentions, two options can be considered: (1) the use of published government forecasts; and (2) the use of forecasts produced by international organisations. In both cases data availability is limited. Moreover, official government forecasts may suffer from systematic biases (see Larch and Salto 2005, for evidence of a systematic tendency to overestimate growth, especially during slowdowns), while forecasts by international organizations do not necessarily reflect government’s expectations (even assuming that they share the same information set). The informational problems associated with the analysis of policy rules have been thoroughly analysed in the context of monetary policy (see, e.g., Orphanides 2001), but have received much less attention with reference to fiscal policy. For an analysis of fiscal policy reaction functions using real-time indicators, see Forni and Momigliano (2005), Golinelli and Momigliano (2006, 2008), Cimadomo (2007), Giuliodori and Beetsma (2008).

We assume that interest spending is not directly related to the output gap. While cyclical conditions affect interest rates, the impact on interest outlays is mediated by the term structure of debt. Nevertheless, the ratio of interest outlays to GDP is affected by cyclical fluctuations in output.

To this end Galì and Perotti (2003) use a different approach. In their estimating equation the dependent variable is the cyclically-adjusted primary balance, which is regressed against its lagged value, the lagged value of debt and a set of control variables, including the deviation of the interest rate from a predetermined Taylor rule. Specifically, they compute the average absolute deviation between each country’s short-term interest rate and the rate generated by the following Taylor rule: r t = 4.0 + 1.5 (π − 2.0) + 0.5 x t , where r is the short-term nominal interest rate and x is a vector of control variables. They argue that this rule is generally viewed as a good first approximation of the behaviour of central banks that have been successful in stabilising inflation and the output gap and such a rule has been shown to have desirable properties when embedded in a dynamic optimizing model with realistic frictions.

Specifically, the data used in this paper are those of the Spring 2008 release of the AMECO dataset.

To avoid end-point bias the Hodrick–Prescott filter is applied to GDP series longer then the regression sample (1960–2009 as opposed to 1970–2007; we used Commission forecasts for the last two years). We tried different values for the smoothing parameter λ and found that econometric results are robust to different choices. For regressions reported in the paper we used output gap estimates obtained by setting λ = 30. See Bouthevillain et al. (2001) for a discussion of the issues involved in the use of the Hodrick–Prescott filter.

We used different partitions of our data set to check that results do not depend on strong responses of a handful of countries. Results were robust across regressions run on subsamples selected according to the average size of countries’ deficit, debt and social security spending. We also ran regressions including an election dummy taking value 1 in the years in which there was an election for the lower chamber of Parliament (source: Armingeon et al. 2006). Results of the regressions (magnitude and significance levels of the regressors) are not affected by the introduction of the dummy. Most importantly the cyclical asymmetry does not change.

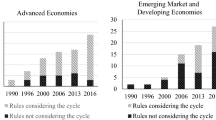

Although the 5-year dummy for the period 1995–1999 was not significant, we ran a similar test for a 1997 break, corresponding to the introduction of the Stability and Growth Pact. The latter supplemented the fiscal rules introduced by the 1992 Treaty establishing a medium-term objective of a budgetary position “close to balance or in surplus”. Also for 1997 we find no evidence of a break in the cyclicality of the overall balance, while there appears to be a further (small) increase in the reaction of the balance to debt. The limited number of observations available suggests caution when interpreting these results.

Our results are in line with evidence suggesting that fiscal rules can be effective in promoting fiscal discipline (on this issue see Kopits and Symansky 1998). Numerous empirical studies suggest that this is the case for the balanced-budget provisions in the USA (see the references in Balassone et al. 2007) and in Swiss cantons (Feld and Kirchgässner 2006). Concerning specifically the Maastricht deficit and debt limits, evidence concerning their positive impact on fiscal performance is provided, for instance, by von Hagen et al. (2000). Concerning the effect of fiscal rules on the cyclicality of fiscal policy, our results (in line with Galì and Perotti 2003) do not support a popular view in the recent policy debate according to which EU fiscal rules have reduced the ability of governments to conduct stabilisation policy. The argument is that during economic expansions, thanks to buoyant revenue, it may be easy to comply with nominal deficit limits even while increasing outlays and this in turn may require the adoption of contractionary fiscal policy during downturns (see the references in von Hagen 2002; Galì and Perotti 2003). Similar concerns have also been voiced with reference to balanced-budget provisions in the USA, where there is evidence that the majority of States appears to fail accumulating sufficient reserves during good times, resulting in procyclical policy in downturns to comply with balanced-budget rules (Sobel and Randall 1996; Levinson 1998; Lav and Berube 1999).

Our results imply that on average euro-area countries were not pursuing fiscal targets consistent with the close-to-balance or in surplus medium term fiscal target defined by Stability and Growth Pact in 1997. This is consistent with the EU Commission assessment of most member states’ fiscal programs after 1998. It is also confirmed by the several breaches of the 3% deficit threshold occurred since then. However, our results cannot be taken to imply that on average fiscal policies of euro-area countries do not ensure fiscal sustainability. The Stability and Growth Pact medium-term target is defined taking into account future increases in expenditure due to adverse demographics and imply a front-loading of the needed adjustment (a lower deficit today to avoid excessive deficit tomorrow under demographic pressure), while the fiscal adjustment assumed in our empirical framework is backward looking (based on linear adaptation) and implicitly assumes a back-loaded fiscal adjustment (i.e. that future deficits will not be allowed to rise under demographic pressures). As noted in Sect. 3.1, since the estimated coefficients of lagged deficit and debt are, respectively, smaller than one and negative, convergence of the equation is ensured, which implies a non-increasing debt ratio, i.e. a sufficient condition for sustainability.

Given that the coefficient for positive output gaps is not statistically significant, it may be argued that asymmetry is significant regardless of the test concerning ϕ.

We run simulations assuming other plausible values for c (ranging between −1 and +1): asymmetry always determines excess debt accumulation and is positively correlated with the size of the budget elasticity to the output gap.

The stock-flow adjustment includes the impact of nominal GDP growth on the debt-to-GDP ratio, as well as differences between the change in debt and the deficit arising within the Maastricht statistical framework (these are due to different accounting criteria, valuation effects and transactions coverage).

A variety of issues arise in the implementation of expenditure rules. These include the choice of the expenditure aggregate to be targeted (items included, institutional coverage, level of disaggregation), the time horizon, the underlying macroeconomic assumptions and the valuation criteria. See, for instance, the discussion in Kumar and Ter-Minassian (2007) and the references therein.

Expenditure rules are used, among others, in Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

More generally, expenditure targeting per se does not correct a structural tendency towards excessive deficits. A constant rate of growth of expenditure can be consistent with a gradual deterioration of the fiscal balance if revenues do not keep the same pace as expenditure. An anchor in terms of budget balance is therefore essential.

References

Alesina A (1987) Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game. Quart J Econ 102:651–678

Armingeon K, Leimgruber P, Beyeler M, Menegale S (2006) Comparative political data set 1960–2004. Institute of Political Science, University of Berne

Artis M, Marcellino M (1998) Fiscal solvency and fiscal forecasting in Europe. CEPR discussion papers 1836

Balassone F, Francese M (2004) Cyclical asymmetry in fiscal policy, debt accumulation and the treaty of Maastricht. Banca d’Italia Temi di Discussione 531

Balassone F, Franco D, Zotteri S (2007) Rainy day funds: can they make a difference in Europe? Banca d’Italia, Occasional Paper 11

Ballabriga F, Martinez-Mongay C (2002) Has EMU shifted policy? European Commission, Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Economic Papers 166

Blanchard O, Chouraqui JQ, Hagemann RP, Sartor N (1990) The sustainability of fiscal policy: new answers to an old question. OECD Econ Stud 15:7–36

Bohn H (1998) The behaviour of US public debt and deficits. Quart J Econ 113:949–963

Bouthevillain C, Cour-Thimann P, Van den Dool G, Hernandez de Cos P, Langenus G, Mohr M, Momigliano S, Tujula M (2001) Cyclically adjusted budget balances: an alternative approach, ECB Working Paper 77

Buti M, Sapir A (1998) Economic policy in EMU: a Study by the European commission services. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Buti M, Franco D, Ongena H (1998) Fiscal discipline and flexibility in EMU: the implementation of the stability and growth pact. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 14:81–97

Cimadomo J (2007) Fiscal policy in real time, CEPII Working Paper 10

Danninger S, Cangiano M, Kyobe A (2004) The political economy of revenue-forecasting experience from low income countries. IMF working paper 05/02

European Commission (2006) Public finance in EMU - 2006, European economy, reports and studies, 3

Feld PL, Kirchgässner G (2006) On the effectiveness of debt brakes: the Swiss experience. CREMA Working Paper Series 21

Forni L, Momigliano S (2005) Cyclical sensitivity of fiscal policies based on real time data. Appl Econ Quart 50(3):299–326

Galì J, Perotti R (2003) Fiscal policy and monetary integration in Europe. Econ Policy 37:535–572

Gavin M, Perotti R (1997) Fiscal policy in Latin America. In: NBER macroeconomics annual. MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp 11–61

Giuliodori M, Beetsma R (2008) On the relationship between fiscal plans in the European union: an empirical analysis based on real time data. J Comp Econ 36(2):221–242

Golinelli R, Momigliano S (2006) Real-time determinants of fiscal policies in the euro area. J Policy Model 28:943–964

Golinelli R, Momigliano S (2008) The cyclical response of fiscal policies in the Euro area. Why results of empirical research differ so strongly? Banca d’Italia Temi di Discussione 654

Hercowitz Z, Strawczynski M (2004) Cyclical ratcheting in government spending: evidence from the OECD. Rev Econ Stat 86:353–361

Kaminsky GL, Reinhart C, Végh C (2004) When it rains, it pours: procyclical capital flows and macroeconomic policies, NBER Working Paper 10780

Kopits G, Symansky S, (1998) Fiscal policy rules. IMF occasional papers 162. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Kumar M, Ter-Minassian T (eds) (2007) Promoting fiscal discipline. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Lane A, Tornell P (1999) The voracity effect. Am Econ Rev 89:22–46

Larch M, Salto M (2005) Fiscal rules, inertia and discretionary fiscal policy. Appl Econ 37:10

Lav IJ, Berube A (1999) When it rains it pours, center on budget and policy priorities report

Levinson A (1998) Balanced budgets and business cycle: evidence from the states. National Tax J 51:715–732

Nordhaus WD (1975) The political business cycle. Rev Econ Stud 130:169–190

Orphanides A (2001) Monetary policy rules based on real-time data. Am Econ Rev 91:964–985

Sobel RS, Randall H (1996) The impact of state rainy day funds in easing state fiscal crises during the 1990–1991 Recession. Public budgeting & finance. Fall, 28–48

Talvi E, Végh C (2000) Tax base variability and procyclicality of fiscal policy NBER Working Paper 7499

von Hagen J (2002) More growth for stability – reflections on fiscal policy in Euroland. Mimeo

von Hagen J, Hughes-Hallett A, Strauch R (2000) Budgetary consolidation in EMU. European economy: Reports and Studies:148. Brussels: European Commission

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balassone, F., Francese, M. & Zotteri, S. Cyclical asymmetry in fiscal variables in the EU. Empirica 37, 381–402 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-009-9114-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-009-9114-7