Abstract

Preterm delivery is one of the strongest predictors of neonatal mortality. A given exposure may increase neonatal mortality directly, or indirectly by increasing the risk of preterm birth. Efforts to assess these direct and indirect effects are complicated by the fact that neonatal mortality arises from two distinct denominators (i.e. two risk sets). One risk set comprises fetuses, susceptible to intrauterine pathologies (such as malformations or infection), which can result in neonatal death. The other risk set comprises live births, who (unlike fetuses) are susceptible to problems of immaturity and complications of delivery. In practice, fetal and neonatal sources of neonatal mortality cannot be separated—not only because of incomplete information, but because risks from both sources can act on the same newborn. We use simulations to assess the repercussions of this structural problem. We first construct a scenario in which fetal and neonatal factors contribute separately to neonatal mortality. We introduce an exposure that increases risk of preterm birth (and thus neonatal mortality) without affecting the two baseline sets of neonatal mortality risk. We then calculate the apparent gestational-age-specific mortality for exposed and unexposed newborns, using as the denominator either fetuses or live births at a given gestational age. If conditioning on gestational age successfully blocked the mediating effect of preterm delivery, then exposure would have no effect on gestational-age-specific risk. Instead, we find apparent exposure effects with either denominator. Except for prediction, neither denominator provides a meaningful way to define gestational-age-specific neonatal mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, Mooney MD, Levitz CE, Schumacher AE, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):957–79.

Linked Birth/Infant Death Records 2007–2013, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program, on CDC WONDER On-line Database [database on the Internet] 2015. http://wonder.cdc.gov/lbd-current.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2015.

Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Basso O. On the pitfalls of adjusting for gestational age at birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(9):1062–8.

Kramer MS, Zhang X, Platt RW. Analyzing risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(3):361–7.

Platt RW, Joseph KS, Ananth CV, Grondines J, Abrahamowicz M, Kramer MS. A proportional hazards model with time-dependent covariates and time-varying effects for analysis of fetal and infant death. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(3):199–206.

VanderWeele TJ, Mumford SL, Schisterman EF. Conditioning on intermediates in perinatal epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):1–9.

Basso O. Implications of using a fetuses-at-risk approach when fetuses are not at risk. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30(1):3–10.

Joseph KS. Incidence-based measures of birth, growth restriction, and death can free perinatal epidemiology from erroneous concepts of risk. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(9):889–97.

Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Basso O, Harmon QE. Re: “Analyzing risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes”. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(3):218.

Ananth CV, Schisterman EF. Confounding, causality, and confusion: the role of intermediate variables in interpreting observational studies in obstetrics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(2):167–75.

Chen XK, Wen SW, Smith G, Yang Q, Walker M. Pregnancy-induced hypertension is associated with lower infant mortality in preterm singletons. BJOG. 2006;113(5):544–51.

Papiernik E, Alexander GR, Paneth N. Racial differences in pregnancy duration and its implications for perinatal care. Med Hypotheses. 1990;33(3):181–6.

Cheung YB, Yip P, Karlberg J. Mortality of twins and singletons by gestational age: a varying-coefficient approach. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(12):1107–16.

Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The effect of placenta previa on neonatal mortality: a population-based study in the United States, 1989 through 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5):1299–304.

Naeye RL. Causes of perinatal mortality in the US Collaborative Perinatal Project. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 1977;238(3):228–9.

Silver RM, Varner MW, Reddy U, Goldenberg R, Pinar H, Conway D, et al. Work-up of stillbirth: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(5):433–44.

Smith GCS. Quantifying the risk of different types of perinatal death in relation to gestational age: researchers at risk of causing confusion. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30(1):18–9.

The Stillbirth Collaborative Network Writing Group. Causes of death among stillbirths. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2011;306(22):2459–68.

Wou K, Ouellet MP, Chen MF, Brown RN. Comparison of the aetiology of stillbirth over five decades in a single centre: a retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e004635.

Hoyert DL, Gregory EC. Cause of fetal death: data from the fetal death report, 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(7):1–25.

Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(14):1–134.

Birth Cohort Linked Birth-Infant Death Data Files [database on the Internet] 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/Vitalstatsonline.htm. Accessed 10 July 2015.

Fetal Death Data File [database on the Internet] 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/Vitalstatsonline.htm. Accessed 16 July 2015.

Basso O, Wilcox A. Mortality risk among preterm babies: immaturity versus underlying pathology. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):521–7.

Talge NM, Mudd LM, Sikorskii A, Basso O. United States birth weight reference corrected for implausible gestational age estimates. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):844–53.

Yudkin PL, Wood L, Redman CW. Risk of unexplained stillbirth at different gestational ages. Lancet. 1987;1(8543):1192–4.

Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Hauth JC, MacPherson C, VanDorsten JP, Klebanoff M, et al. Preterm delivery in women with pregestational diabetes mellitus or chronic hypertension relative to women with uncomplicated pregnancies. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1520–4.

Feig DS, Hwee J, Shah BR, Booth GL, Bierman AS, Lipscombe LL. Trends in incidence of diabetes in pregnancy and serious perinatal outcomes: a large, population-based study in Ontario, Canada, 1996–2010. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1590–6.

Knorr S, Stochholm K, Vlachova Z, Bytoft B, Clausen TD, Jensen RB, et al. multisystem morbidity and mortality in offspring of women with type 1 diabetes (the EPICOM study): a register-based prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):821–6.

Basso O, Wilcox AJ. Might rare factors account for most of the mortality of preterm babies? Epidemiology. 2011;22(3):320–7.

Platt RW. The fetuses-at-risk approach: an evolving paradigm. In: Louis GB, Platt RW, editors. Reproductive and perinatal epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):262–73.

Lisonkova S, Paré E, Joseph K. Does advanced maternal age confer a survival advantage to infants born at early gestation? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):87.

Ananth CV, VanderWeele TJ. Placental abruption and perinatal mortality with preterm delivery as a mediator: disentangling direct and indirect effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(1):99–108.

Auger N, Naimi AI, Fraser WD, Healy-Profitos J, Luo ZC, Nuyt AM, et al. Three alternative methods to resolve paradoxical associations of exposures before term. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(10):1011–9.

VanderWeele TJ. Commentary: resolutions of the birthweight paradox: competing explanations and analytical insights. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(5):1368–73.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments on earlier drafts by Dr. Donna Baird, Dr. David Umbach, and anonymous reviewers.

Funding

This research has been supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Publicly available data with no identifying details were used. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

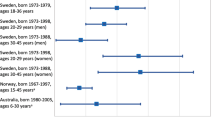

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harmon, Q.E., Basso, O., Weinberg, C.R. et al. Two denominators for one numerator: the example of neonatal mortality. Eur J Epidemiol 33, 523–530 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0373-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0373-0