Abstract

This paper analyses the returns to publicly performed R&D investments in 22 OECD countries. We exploit a dataset containing time-series from 1963 to 2011 and compare the estimates of different types of production function models. Robustness analyses are performed to test the sensitivity of the outcomes for particular specifications, sample selections, assumptions about the construction of R&D stocks, and variable definitions. Analyses based on Cobb–Douglas and translog production functions mostly yield statistically insignificant or negative returns. In these models we control for private and foreign R&D investments and the primary production factors. Models including additional controls, such as public capital, the stock of inward and outward foreign direct investment, and the shares of high-tech imports and exports, yield more positive returns. Our findings suggest that publicly performed R&D investments do not automatically foster GDP and TFP growth in production function models. Furthermore, our estimates suggest that economic returns to publicly performed R&D seem to depend on the specific national context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Technological progress is the ultimate driver of productivity growth and hence of modern economic growth. The economic literature has devoted a lot of effort to investigating the role of technological progress and skilled labour in explaining economic growth (e.g., Schumpeter 1934; Abramovitz 1956; Kaldor 1957; Solow 1957; Kuznets 1966; Griliches 1979; Freeman et al. 1982; Fagerberg 1988; Maddison 2007). However, formal growth theory explicitly modelled technological progress only from the late 1980s onwards, long after research and development (R&D, one of the main sources of technological progress) had been integrated into the production function by Griliches (1979). In the field of “endogenous growth theory” that emerged from formalizing the insights about the relationship between technological progress and economic growth, attention has been focused on the interactions between technology, physical capital and human capital (e.g., Romer 1986, 1990; Lucas 1988). Basically, endogenous growth theory has added the stock of ideas and human capital to the familiar inputs of physical capital and workers into the production function (e.g., Grossman and Helpman 1991; Aghion and Howitt 1992; Jones 2002).

Research and development (R&D) is one of the main sources of technological progress, and it is performed both by private companies and government institutions. Currently, about 30% of total R&D investments in the OECD area is performed by the government and the higher education sector.Footnote 1 The reason for government involvement is that ideas are non-rival and risky to explore by private companies, which could lead to suboptimal levels of R&D investment from a societal point of view. Government intervention internalizes some of the externalities in the production of ideas and human capital that could otherwise lead to suboptimal outcomes (Brown et al. 2012). Examples of government interventions include government funding to foster research in universities, adopting appropriate education policies to stimulate the absorptive capacity of the economy and designing responsive institutions. Indeed, there is historical evidence about specific government-funded projects leading to substantial economic payoffs in the private sector (Mazzucato 2013).

The systematic measurement of the returns to investments in science, technology and innovation (STI) is extremely complex. This is especially the case for publicly performed R&D.Footnote 2 A number of complicating factors arise: returns are volatile, key variables (such as ideas, human capital and institutions) are correlated, investments serve multiple goals (e.g., radical innovation and imitation) and the chain of effects is long and often observed indirectly only in statistics. The returns to public R&D investments are even more challenging to capture than private R&D investments as they are for example more likely to spill over to other areas of society, industries or countries, which makes it hard to capture them in terms of measures of productivity growth.

In this paper we empirically assess the macro-economic relationship between publicly performed R&D investments and productivity growth. We do so by estimating several production function models applied in the empirical literature. This way our research contributes to the empirical literature on endogenous growth models by presenting an overview of empirical results. Up to this point the body of econometric studies that rely on production functions to estimate the impact of government-funded R&D shows mixed results. We present new estimates and compare the estimates of the most commonly used specifications in the literature with each other. Our contribution lies in the focus on publicly financed R&D, our agnostic approach to the production function and our unique panel dataset of 22 OECD countries in the period 1963–2011. This long time period is important, not only from a statistical point of view, but also because of the long lags involved in the relationship between public investments in R&D and productivity growth.

We estimate three types of models that have also been used in studies estimating the returns to firm R&D efforts. We start by estimating Cobb–Douglas production functions that include public, private and foreign R&D, and the usual primary production factors as inputs.Footnote 3 These models assume log-linearity and constant returns to scale. This seems to be the most restrictive approach in light of the complexity of the relationship between technology and economic growth (Griliches 1998; Jones 1998).

We proceed by estimating two types of models that allow for country-specific returns to R&D by including interaction terms between the different input factors. First, we estimate translog models that allow for a more flexible production function and include inputs similar to the Cobb–Douglas models. Second, we follow an approach suggested by the OECD to estimate augmented production function models (Khan and Luintel 2006). These models introduce additional inputs (such as public capital, the stock of inward and outward foreign direct investment, and the shares of high-tech imports and exports) that are aimed specifically at capturing the variability in rates of return to R&D. The latter two approaches are inspired by insights from the theory of innovation systems (Lundvall 1992; Nelson 1993; Freeman 1995; Soete et al. 2010), which stresses that rates of return to (public) R&D investments differ across countries because of differences in for example the availability of actors, their capabilities, the institutions and culture in the specific country, the specific kinds of R&D invested in or the specific public sectors that perform the R&D (e.g., universities vs. public labs).

For our analyses we use data on R&D expenditures from the OECD’s Main Science and Technology Indicators (MSTI) and on economic measures from the Penn World Tables (PWT). We carry out robustness analyses to test the sensitivity of the outcomes for particular model specifications, sample selections, assumptions with respect to the construction of R&D stocks, and variable definitions. By comparing various estimation methods, we obtain a balanced view of the relationship between indicators of economic development and public R&D investments and provide guidelines for estimating the macroeconomic returns of STI, in particular the economic effects of public investments.

The picture that emerges from our research is consistent with the macroeconomic econometric literature in this relatively small field of study: the relationship between public R&D investments and productivity growth is not very robust. The findings seem to depend on the model specifications and variable definitions. The Cobb–Douglas models yield mostly statistically insignificant returns, with estimated elasticities varying from − 0.12 to 0.09. The translog models yield mostly statistically significant negative elasticities, with point estimates ranging from − 0.29 to 0.01. In the augmented models most of the estimated elasticities are positive and statistically significant. Point estimates are in a range from − 0.02 to 0.07.Footnote 4 This broad range of estimates suggests that public R&D investments do not automatically foster measured productivity and/or economic growth. In addition, the estimated coefficients suggest that the economic returns to publicly performed R&D depend on the specific national context in which they are executed.

We are reluctant to draw firm policy conclusions from these production function models because the scope of conclusions that can be drawn from our macroeconomic cross-country perspective is limited. First, causal inferences should be avoided, especially given the high persistence of the stock variables over time and the strong interdependencies between the several input factors—features also addressed in previous studies we discuss below. Second, the estimated coefficients show the economic impact of publicly performed investments in science, technology and innovation and do not necessarily fully address the potential broader societal impact. Third, we are unable to assess the returns to specific types of measures to foster productivity growth or economic development. Our country-level variables are broad indicators that include expenditures on various types of R&D and on R&D performed by different public sectors. In addition, macro-economic analyses directly assess the impact of STI on economic growth and provide only limited insight into the complex underlying mechanisms, although our more flexible production functions go a long way into this direction.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 reviews the economic literature on the effects of public R&D investments. Section 3 addresses the theoretical insights underlying our three main empirical approaches. Section 4 presents the data and Sect. 5 provides a detailed description of our methodology. Section 6 presents the estimation results. Section 7 concludes and discusses our findings.

2 Literature Review

There exists a literature that addresses the economic value of scientific research. An early summary of this literature that attempts to estimate the returns to publicly funded R&D is provided by Salter and Martin (2001). They identify three main methodological perspectives: econometrics, surveys and case studies. The (few) case studies that Salter and Martin survey attempt to trace the impact of government-funded research, and usually do not yield quantitative estimates of the return. The econometric studies included in their study are mostly aimed at specific government R&D programs, usually successful ones so that a sample selection bias does exist. These econometric studies are mostly aimed at the United States and show high rates of return (ranging from 20 to 67%). The survey work summarized by Salter and Martin was initiated by Mansfield (1991), who asked company managers how many of their products (and what proportion of sales) could not have been developed without the aid of government-funded basis research, or which received ‘substantial aid’ from this kind of research. Using the results of the survey, Mansfield calculates a rate or return of 28% to government-funded basic research.

Gheorghiou (2015) extends the overview by Salter and Martin by surveying 27 studies on the economic returns of publicly funded research, including 12 studies that were published after Salter and Martin’s (2001) review. These studies use the same variety of methodologies as observed by Salter and Martin, and also yield a wide variety of indicators on economic returns. 12 of the 27 studies can be characterized as case studies of specific government-funded R&D projects. All these studies report revenues being a multitude of investments, although they do not yield specific rates of return. Another group of 5 studies looks at the use of publicly-funded research by private firms, either by surveys or by looking at citations made in patents to the scientific literature. This yields an estimate of which fraction of private sector innovation projects (or patents) would not have been possible without public science projects feeding knowledge into them. The percentage ranges from 2 to 75% (the 75% refers to patents). The last category of studies surveyed by Gheorghiou includes ten studies that yield specific estimates of the rate of return to public R&D, either by using econometric modelling, or by the techniques that Mansfield (1991) pioneered. These rates are always positive, and vary between 12 and 100%.

The econometric literature on the economic returns to R&D investments largely focuses on the impact of private R&D investments on economic growth and productivity (Hall et al. 2010). The number of empirical studies that explicitly takes public R&D into account is limited. Table 1 summarizes the findings of the most important studies in this area, conducted at the country level. We include only studies which focus directly on the impact of public R&D investments on GDP or TFP (growth).

The advantage of using country-level data (rather than firm- or sector-level data) is that all types of potential spillovers are (implicitly) captured at the aggregated output measures. These macro-econometric studies, presented in Table 1, explicitly distinguish between public and private R&D. The studies differ in terms of their sample and in terms of their dependent and independent variables. Some papers investigate GDP (per capita) growth directly, whereas other use productivity (TFP) as the main outcome. The included R&D variables are expressed either in terms of flows of spending as a percentage of GDP or in terms of stocks of spending. Most of the studies use panel data exploiting both differences across countries and over time. Two of the studies only use cross-section (Lichtenberg 1993) or time-series (Haskel and Wallis 2013) information.

The estimated effects of public R&D investments on economic growth or productivity vary widely, ranging from significantly positive to significantly negative coefficients. Positive coefficients are found by Guellec and Van Pottelsberghe (2004), Khan and Luintel (2006) and Haskel and Wallis (2013). The first two of these studies distinguish public R&D from private and foreign R&D and estimate the effects on productivity. Guellec and Van Pottelsberghe use an error-correction model to address both short-term and long-term dynamics and conclude that public R&D has a positive long term impact on productivity. The estimated elasticity for public R&D of 0.17 is even larger than that for private R&D (0.13).

Khan and Luintel (2006) set out to reproduce these results, but fail when using the same model with more recent data and a slightly different set of countries. However, when they estimate a model that includes additional explanatory variables such as public infrastructure, foreign direct investments and the share of high-tech imports and exports, they find positive rates of return to public R&D. The model with these additional variables is aimed at capturing the heterogeneity of rates of return across countries, a topic to which we return extensively below. The average estimated elasticity across 16 OECD countries equals 0.21.

A recent study for the United Kingdom by Haskel and Wallis (2013) distinguishes between different kinds of public R&D, including R&D disbursed through the research councils in the country. They find a robust correlation between R&D channelled through research councils and TFP growth, while overall public R&D does not correlate positively with TFP growth.

Coe et al. (2009) employ a larger dataset and similar methodology to the Guellec and Van Pottelsberghe (2004) to reach a different conclusion. They “included measures of publicly financed R&D but did not find that these were significant or robust determinants of total factor productivity” (p. 730). A panel study by Park (1995) also yields negative, but statistically insignificant effects. Two studies even find significant negative effects. Bassanini et al. (2001) use panel data for 15 OECD countries and include both private and public R&D intensities as independent variables. They find a positive estimated effect for private R&D (0.26) and a negative effect for public R&D (-0.37). The authors point to crowding out of private R&D initiatives as a potential explanation for the negative effects of public R&D. In addition they mention that publicly performed research may not be directly targeted at productivity improvements, but rather at generating basic knowledge. The impact of basic knowledge on economic performance is difficult to identify because of the time lags involved and the complex interactions leading to technology spillovers. Lichtenberg (1993), who performs a cross-sectional analysis using average R&D intensities (but not foreign R&D) of 53 countries, also finds negative effects. He argues that a large fraction of public R&D funds is spent on research that does not directly benefit economic growth, such as medical and humanities research.

The picture that emerges from this literature review of macroeconomic studies is that the relationship between public R&D investments and productivity and/or economic growth is not very robust. The findings in these studies seem to depend on the model specifications and variable definitions. Our approach aims to contribute to the literature by estimating and comparing the estimates of the most commonly used specifications. This provides a broad overview of estimates of various macroeconomic approaches. In comparison to previous studies, we build a panel database (n = 967) with a long time series (1963–2011) for a large number of countries (22 countries). This is important, not only from an empirical point of view, but also because of the long lags involved in the relationship between public R&D investments and economic outcomes. A comparison of the outcomes of different production function models, estimated on a single large dataset, can help explaining the mixed results that have been found in previous studies.

A complementary strand of the literature addresses the relationship between public and private R&D investments. Zúniga-Vicente et al. (2014) and Becker (2015) provide systematic and careful reviews of the economic literature about the effects of public R&D policies on private R&D investment. Empirical findings in this literature turn out to be mixed. Evidence from the most recent studies suggest that public R&D policies are likely to foster private R&D investments, while earlier work has found that public efforts are more likely to result in crowding-out effects. Public R&D support seems relatively effective in stimulating the private R&D investments of small firms, which experience financial constraints (Becker 2015). Inspired by the ambiguous results in the empirical literature, Dimos and Pugh (2016) perform a meta-regression analysis of 52 micro-level studies. The analysis rejects crowding-out effects, but also does not find evidence of substantial additionality. Other studies have investigated the impact of publicly funded R&D on productivity gains in specific sectors. Most of these studies find no clear evidence of a productivity effect (Griliches and Lichtenberg 1984; Bartelsman 1990). Some studies conducted at the industry level in the United States, however, find a positive impact of public R&D investments on productivity growth in specific (high-tech) manufacturing industries (Nadiri and Mamuneas 1994; Mamuneas and Nadiri 1996; Mamuneas 1999).

3 Models

Our empirical strategy is based on three broad categories of models: one that is derived directly from a simple production function framework (Cobb–Douglas models), one that attempts to introduce more flexibility in the production function, and does so using an assumption of strong optimality (translog models), and finally one that introduces more flexibility and uses a less strict set of assumptions about optimality (augmented models). The approaches have advantages and disadvantages. We do not a priori come down at the side of a particular model but estimate and interpret the whole range of estimated coefficients.

The Cobb–Douglas models build on growth models and follow the tradition of the work on R&D and productivity in the private sector, as pioneered by Griliches (see 1998, for an elaborate overview). This approach postulates a production function with value added (GDP) as the output variable, a set of “traditional” input variables (employment, capital stock), and R&D-related knowledge stocks. It typically looks at cumulated R&D variables (R&D stocks) rather than current R&D outlays (R&D flows). Various types of knowledge capital are likely to affect economic growth through different mechanisms. Human capital investments directly improve the skills of the labour force; private R&D leads to improved products, processes and services; public R&D improves scientific knowledge via basic (or applied) research performed by universities or other public institutions; and foreign R&D affects a country’s productivity through cross-border knowledge flows or spillovers (Coe and Helpman 1995; Verspagen 1997; Soete and Ter Weel 1999). The impact of foreign R&D on a country’s economic performance depends on its absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal 1990), the latter of which in turn can be enhanced by human capital (Engelbrecht 1997) and domestic R&D investments. We explicitly distinguish between different sources of knowledge contribution to economic progress by including human capital and three types of R&D capital (public, private and foreign) in the production functions.Footnote 5 In its simplest form, this approach uses a Cobb–Douglas production function, yielding a single equation (in logs) for estimation. A drawback of this model specification is that it assumes that the rates of return to the inputs are constant and hold sample-wide.

There are good theoretical reasons to expect that the assumption of the Cobb–Douglas production function is too restrictive.Footnote 6 Next to presenting estimates for Cobb–Douglas production functions we therefore estimate models which allow for heterogeneity across countries. Our second framework is the translog production function (Christensen et al. 1973). This follows in the same tradition of production functions, but, by adding interaction terms between the input variables, builds flexibility into the production function. In effect, the rates or return depend on the level of the inputs (this will be explained formally below). Thus, the rates of return on public (or private) R&D can become dependent, for example, on the capital-to-labour ratio used in the country’s production process, or on the ratio between public and private R&D. This causes heterogeneity in the estimated rates of return across countries because of differences in the levels of the inputs.Footnote 7 However, the flexibility that the translog production function provides comes at the price of increased demands on rationality of the involved actors. The translog production function itself is a very flexible way of modelling the production process, which implies that to “discipline” its estimated coefficients, additional rigor has to be imposed by estimating it jointly with other equations. In practice, this is done by combining the production function with a number of first-order conditions of the profit-maximizing (or cost-minimizing) problem. This takes the form of additional equations for the factor shares of the inputs used in the production function.

The third theoretical perspective that we apply takes the flexibility (and variability) of rates of return a step further, and relaxes the optimality assumptions of the translog production function. It follows from the approach developed by the OECD (Khan and Luintel 2006) and introduces additional variables that are solely aimed at capturing the variability in rates of return to R&D. We call this type of models ‘augmented production function models’. This approach introduces interactions between the R&D variables and the newly introduced variables, thus in effect making the rates of return dependent on these new variables. By using the newly introduced variables in combination with the estimated parameters, the rates of return to the R&D variables can be calculated for each country, with the variation in the additional variables directly translating into variability of the rates of return to R&D across countries. This model is inspired by the idea that the returns to R&D can be dependent on country-specific policies. Hence, adding economic variables that capture such policy differences may help building in more realism. A drawback of this approach is the large number of parameters to be estimated. Similar to the translog models, this requires restrictions on parameter values, all the more since the available sample of (additional) data is smaller. We discipline the estimates by using a stepwise estimation procedure. Another drawback of this approach is that it lacks a clear theoretical foundation regarding the choice of the additional input factors. Obviously, the quality of the estimates of the rates of return will depend on whether the adequate set of controls has been introduced.

4 Data

For our analysis we use a combined dataset containing information on R&D expenditures from OECD’s Main Science and Technology Indicators (MSTI) and economic measures from the Penn World Tables (PWT) for a large set of countries over a relatively long time period. We use R&D expenditures as the only indicator for “public science”, in full recognition of the fact that this is an incomplete measure. Also, we define “public science” on the basis of who performs the R&D (rather than who funds it), and use a broad categorization of “public”. In particular, we consider all R&D that is not performed by private firms as public. In effect, this includes the government sector (public R&D labs), the higher education sector (universities), and the private non-profit sector. The latter is usually a small fraction of total public R&D. Because of limited data availability we make no attempt to break down public R&D by sector, field of science, or by military versus civil use.

4.1 Data Description

Our dataset combines two main sources. First, we use OECD data on R&D expenditures per country: the Main Science and Technology Indicators (MSTI). The OECD has collected such data since 1963 based on the guidelines in the Frascati Manual. We dispose of MSTI data on public and private R&D expenditures for 40 countries in the period 1963–2011 (maximum).Footnote 8 This is an unbalanced panel: information on R&D expenditures is not available for each country and each year. Information on R&D expenditures becomes available for a larger set of countries in more recent periods: in 1963 this includes 6 countries, in 1972 19 countries, in 1981 22 countries, in 1994 33 countries and in 2007 40 countries.

In our main analyses we restrict the estimation sample to 22 countries for which data are available from 1980. This is a set of highly developed countries including Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, United Kingdom, Greece, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Portugal, Sweden and the Unites States. In the analyses we use all available data over the whole period 1963–2011 for each of these countries. This concerns on average 44 years per country. The total estimation sample consists of 967 observations.

We use the gross domestic expenditures on R&D (GERD) as an indicator of total R&D expenditures and the gross domestic expenditures on R&D performed by the business enterprise sector (BERD) as an indicator for the private R&D expenditures. Public R&D expenditures are defined as the difference between total and private R&D expenditures (GERD-BERD). This variable contains all resources devoted to research performed by universities and other public research institutions.Footnote 9

Second, we use data on economic variables for each of these countries from Penn World Tables (PWT). As outcome variables we use real gross domestic product (GDP) and total factor productivity (TFP). GDP is in constant national prices (2005 US dollars) and TFP is an index variable that takes value 1 for each country in 2005. In addition, we use physical capital (K), employment (L) and a human capital index (H) as additional production factors.Footnote 10

In the augmented models we add explanatory variables to the traditional production factors. These variables include public capital, the stock of inward and outward foreign direct investments (FDI) and the share of high-tech imports and exports. In doing so, we follow the approach suggested by Khan and Luintel (2006). Data on public capital stocks are shares of public capital in total capital, multiplied by our capital stock variable from PWT. The shares of public capital are taken from UN national accounts database supplemented with various national sources. Data on FDI (inward and outward stocks as percentage of GDP) are taken from the UNCTAD online database. Data on high-tech imports and exports are taken from the UN trade database using definitions of high-tech by OECD. These data are only available for the period from 1981 and missing for Greece, Iceland and New Zealand, so that these countries are missing from the estimations that include these variables.Footnote 11

The R&D data from MSTI come from the currently publicly available records from 1981 and an older version from the UNU-MERIT archives. The amounts in the older dataset were translated into euros for the appropriate countries. To deal with small breaks in the data for the UK, the US and Sweden in 1981, we back casted the old observations using a factor based on the 1981 ratio. For each country and year we determined the ratio of R&D expenditures over GDP in current prices national currencies. This gives the yearly R&D flow variables expressed in fractions of GDP. Missing observations were interpolated linearly, as suggested in Verspagen (1997).

4.2 Construction of Knowledge Stocks

Most of the economic theory that deals with the returns to R&D investments uses the concept of knowledge capital stocks. The idea is that R&D investments create a knowledge stock that affects economic performance in the future. Such knowledge stock depends on all previous and current R&D investments, taking into account the depreciation of knowledge capital over time. Consistent with most of the literature we construct knowledge stocks using the perpetual inventory method. This implies that the current stock is constructed using the previous stock and adding the current expenditures minus a deprecation of the knowledge stock:

where KCit is the knowledge capital stock of country i in year t, δ is the depreciation rate of knowledge capital and Rit denotes the R&D expenditures of country i in year t.

A well-known issue regarding the use of R&D stocks is R&D double-counting (Schankerman 1981). Since R&D expenditures consist also of labour and capital costs, these inputs are likely to be counted twice. Unfortunately, we do not dispose of data on the inputs that are cleared of their R&D components. Empirical evidence suggests that potential biases in estimated R&D elasticities due to R&D double-counting can be either upward or downward (Hall et al. 2010).

To obtain absolute values of R&D expenditures (Rit) we multiplied the flow variable on R&D by our measure for real GDP from PWT. Different assumptions can be made with respect to the depreciation rate. In our main analyses we use a rate of 15% and we test for the robustness of the results to other rates. The determination of the initial knowledge stock furthermore requires assumptions on the pre-sample growth rate. We choose the pre-sample growth rate such that the difference between that growth rate and the growth rate between the first and second period is minimized for each country. Alternatively, we use a single pre-sample growth rate of 5% in our robustness analyses. In order to construct foreign knowledge capital stocks we need additional assumptions on knowledge spillovers between different countries. We construct foreign knowledge capital stocks using weights based on bilateral migration flows. Hence, a country’s R&D expenditures per capita spread out to all other countries using the number of migrants as weights.Footnote 12 The following formula represents this relationship, where i is the destination country and j is the origin country:

The idea is that migration flows reflect the amount of knowledge exchange between countries. Alternatively, we construct foreign knowledge stocks using weights based on distance between countries. In addition, we perform a sensitivity analysis in which we construct the foreign R&D variable using weights based on international trade flows.Footnote 13

4.3 Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the average values by country over time of some important variables. The public and private R&D variables are shown as ratios of GDP. The average public R&D expenditures vary from 0.3% in Spain and Greece to 0.9% in the Netherlands and Iceland. The private R&D expenditures differ more strongly among countries and take values between 0.1% in Greece and 1.9% in Switzerland and Sweden. Differences in employment are mainly due to country size. The human capital index is based on completed education levels and takes values between 1 and 5.Footnote 14 Average yearly economic growth has been lowest in Greece (1.4%) and largest in Japan (4.1%) over the relevant time period. The last two columns present the initial year in the dataset and the consequent number of observations for each country. The number of observations varies from 31 (for countries whose initial data have become available in 1981) to 49 (for countries whose initial data have become available in 1963).

Figure 1 shows the development of GDP and public R&D expenditures for each country over time. The resulting patterns do not show a large volatility over time. Most of the countries have gradually increased their R&D expenditures in absolute terms, and as a share of GDP. In some countries, such as the Netherlands, R&D expenditures, as a share of GDP, have been reasonably stable over time, while few countries, such as the United Kingdom, have decreased the R&D expenditures over the years.

Development of GDP and spending on public R&D over time (index numbers, first year = 1). Note Country codes are listed in Table 2

Table 3 presents the correlations between the most important variables in the analyses. In this table the logarithmic transformation of the stock variables are included, since these are used in the empirical analyses. The public R&D stock turns out to be strongly correlated to the private R&D stock as well as to the other primary production factors (physical capital and labour). The private R&D stocks are strongly related to the other production factors as well. Each of these input factors is also strongly correlated to the level of GDP, but less (and negative) to yearly GDP growth. The limited variation in public R&D expenditures over time and the strong correlation with other input factors complicates the empirical analysis of the isolated impact of public R&D on economic growth and productivity.

Figure 2 depicts the relationship between the growth rate of the public R&D stock and next year’s GDP growth rate. Each observation presents public R&D growth and related GDP growth in a specific country and year. The growth rate of the public R&D stock depends on the yearly investments, the previous stock and the deprecation rate (here, we assume a 15% depreciation rate). The pattern suggests no clear relationship between the growth of the public R&D stock and R&D growth.

Relationship between public R&D (growth) and GDP (growth). Note Country codes are listed in Table 2. Each dot presents a country-year observation. N = 967

5 Methods

The functional form of the production function has a large influence on the results (Mohnen 1992). To assess the effect of the functional form on the estimated coefficients of the return to public R&D, we estimate both the very stringent Cobb–Douglas production function and the very flexible translog production function. We define knowledge capital both in stocks and in flows. The Cobb–Douglas function is estimated for GDP as well as TFP, and also estimated in an error-correction framework. In the augmented models we extend the production functions further by adding other variables that may affect productivity or the effectiveness of knowledge investments.

5.1 Cobb–Douglas Production Functions

We extend the Cobb–Douglas function by including knowledge capital. In line with Mankiw et al. (1992) we include a variable for human capital (H). We split domestic knowledge stocks as in Hall et al. (2010) into a private (\(KC_{{}}^{P}\)), a public (\(KC_{{}}^{G}\)), and a foreign (\(KC_{{}}^{F}\)) knowledge stock. This yields the following production function:

where \(Y_{it}\) is total production of country i in year t,\(K_{it}^{{}}\) is the stock of physical capital, \(L_{it}^{{}}\) is the labour stock, and \(A_{it}\) is country- and time-specific technology. In the default specification we assume the effect of the knowledge stocks to be lagged by one year.

To estimate the model, we make a number of adjustments. First, we take labour and human capital together in a quality-adjusted labour variable LH. Second, we normalize Y and K by LH. Third, we split \(A_{it}\) into a time-specific technology (\(\varOmega_{t}\)) component and a country-specific trend. Finally, we take logs on both sides and estimate the model in first differences. This yields estimation Eq. (4):

where \(\phi = \alpha + \beta - 1\). Changes in time-specific technology (\(\Delta \omega_{t}\)) are captured by including year dummies. Differences in the time trend across countries are captured by country fixed-effects \(\mu_{i}\).Footnote 15

When knowledge capital is defined in stocks, as in Eq. (4), the effect of public R&D is estimated as a constant elasticity:\(\tau = \frac{\partial Y}{{\partial KC^{G} }}\frac{{KC^{G} }}{Y}\). To estimate the model based on flows in R&D, let’s first define \(\rho = \frac{\partial Y}{{\partial KC^{G} }}\) as the marginal productivity of public R&D capital. Similarly, we define \(\chi\) and \(\zeta\) as the marginal productivities of private and foreign R&D. Second, the yearly change in knowledge capital is \(\Delta KC_{it} = - \delta KC_{i,t - 1} + R_{it}\), where \(\delta\) is the depreciation rate of knowledge capital and \(R_{i,t}^{{}}\) are R&D expenditures in year t. Finally, if we assume that \(\delta\) is sufficiently small, we can use \(\Delta KC_{it} \approx R_{it}\) and rewrite Eq. (4) asFootnote 16

Instead of assuming a constant elasticity \(\tau\), Eq. (5) assumes a constant marginal product \(\rho\).When we further assume a constant discount rate r, \(\rho\) can be given the interpretation of the gross internal rate of return (not corrected for depreciation).

The elasticity \(\tau\) and the rate of return \(\rho\) are related through \(\frac{{KC^{G} }}{Y}\) so that estimates obtained for one can be easily translated into estimates of the other. In practice, however, the ratio of knowledge capital to GDP can vary substantially over time and across countries, so that estimating the model in flows instead of stocks can make a large difference for the estimated effects (Hall et al. 2010). Given this sensitivity, we will present estimates based on stocks as well as flows.

Another approach we can take to estimate the return to public knowledge capital is by estimating a model for total factor productivity (TFP). When we assume constant returns to scale, perfect competition and profit maximizing firms, we can replace α and β in Eq. (3) by the income shares of capital (\(\hat{\alpha }\)) respectively (quality adjusted) labour (\(\hat{\beta }\)). Then, we can construct

and rewrite Eq. (3) as

When we take logs and first differences we get estimation equation

for a TFP model in stocks, and

for the model in flows.

5.2 Error Correction Models

To assess the effect of model specification on the estimations, we also estimate error correction models (ECMs) for the Cobb–Douglas production function. ECMs are also used by Guellec and Van Pottelsberghe (2004). The ECMs allow for the distinction of short-term from long-term effects. The idea is that in the long run the economy tends towards a stable (equilibrium) relationship between output (Y) and labour inputs, and the physical capital and knowledge capital stock (these variables are likely to be co-integrated),Footnote 17 but that the short term impact of the shocks in the inputs might be different. Since we are primarily interested in a single co-integration relationship, namely between output (Y or TFP) and its input variables, we do not estimate a multivariate ECM but only a conditional ECM for output. For y this model is specified as

To be consistent with the approach of Guellec and Van Pottelsberghe (2004), we do not normalize all variables by lh, but directly include them on the right hand side of the equation. The change in y is now a function of short run effects of shocks in the input variables (the \(\beta\) s) and an adjustment towards the long-term relationship between the level y and the level of its input variables (defined by the effects of the lagged levels of y (\(\theta\)) and the inputs (the \(\gamma\) s)). To stay close to the model in Eq. (4) we constrain all parameters to be equal across countries. The long-term elasticity of \(KC_{{}}^{G}\) is given by \(- \gamma /\theta\).Footnote 18 A similar model is also specified for TFP. We again include country dummies (\(\mu_{i}\)) to enable differences in growth rates across countries.

5.3 Translog Production Functions

A translog production function allows us to deviate from the restrictive assumptions in the Cobb–Douglas model. In the translog production function second order effects and interaction terms are included. The specification of the model is

Calendar years are included using a (log) linearized time variable T, which allows the inclusion of interaction effects between calendar year and the other variables in a relatively parsimonious way. Country dummies are included (\(\mu_{i}\)), but these do not interact with the other variables. The larger functional flexibility comes at the risk of overfitting. We follow the literature and include a number of first-order conditions based on profit-maximizing behaviour by firms which are estimated simultaneously. More specifically, we assume that the relative prices of physical capital, labour and private knowledge capital are equal to their marginal returns. This implies that their income shares are equal to their elasticities, or:

where \(P_{j}\) is the rental price of input factor j.Footnote 19

These three restrictions are estimated simultaneously with Eq. (9) using seemingly unrelated regression (SUR).

The marginal effect of public knowledge capital now depends on the levels of all factors. The elasticity is:

We report the marginal effects at the population sample average of each variable.

5.4 Augmented Production Functions

In addition to the Cobb–Douglas and translog production functions we estimate models that include additional variables and their interactions. We follow as the approach developed by the OECD (Khan and Luintel 2006) and add publically financed physical capital (\(K^{G}\)), the share of high tech imports in all imports (\(HT_{{}}^{imp}\)), the share of high tech exports in all exports (\(HT_{{}}^{exp}\)), and inward and outward foreign direct investment (\(FDI_{{}}^{in}\) and \(FDI_{{}}^{out}\)). Given the additional set of parameters needed to estimate this model, we only focus on the model for TFP here. To stay close to the original approach, we estimate the models in levels instead of first differences and add lagged TFP as an explanatory variable. For the same reason, we include human capital as a separate indicator instead of using a measure of quality adjusted labour.

First, we include only level effects of the additional variables. This gives

Second, we also add interactions between the different variables. To keep the model somewhat parsimonious we differentiate between a set of core variables (\(H,k_{{}}^{G} ,kc_{{}}^{P} ,kc_{{}}^{G}\)) and non-core variables (\(kc_{{}}^{F} ,HT_{{}}^{imp} ,HT_{{}}^{\exp } ,FDI_{{}}^{in} ,FDI_{{}}^{out}\)). The core variables interact with each other and with the non-core variables. This gives

Similar to the translog function, we need to implement some restriction on the functional form to prevent overfitting, the more since the number of observations is smaller. We restrict the number of parameters by using a two-step method. In the first step, we estimate the full model. In the second step, we remove some statistically insignificant variables according to a cut-off p value, and re-estimate the model. In the main estimations we only remove interaction variables between core- and non-core variables using a p value of 0.2.

6 Estimation Results

This section presents and discusses the estimation results. Before we turn to the estimation results, we first analyse the order of integration of our time series. We also analyse whether the long-term relationship between the time series is stable by performing co-integration tests. The results can be found in “Appendix 1”. We perform various panel unit root tests on the log-transformed series of all the variables in the standard production functions. This yields mixed findings. The Levin-Lin–Chu (LLC) test, using a common autoregressive parameter for all countries, rejects the null hypothesis of integration except for tfp, and \(\frac{{R_{{}}^{P} }}{{Y_{{}} }}\),\(\frac{{R_{{}}^{G} }}{{Y_{{}} }}\), \(\frac{{R_{{}}^{F} }}{{Y_{{}} }}\). The Im-Pesaran–Shin (IPS) test, using a different autoregressive parameter for each country, confirms the null-hypothesis of all variables having a unit root, except for foreign knowledge capital. The results for the de-trended versions of these tests are more mixed.

We proceed by assessing whether there is a co-integration relationship between the time series. We follow Boswijk (1994) and perform a Wald test on the joint significance of the adjustment parameter and all long-term parameters. This test is performed using a fixed-effect conditional error correction model (ECM) for y and tfp, using country-specific parameters for the short-term effects and the adjustment towards the long-run relationship. We perform the Wald test for each country separately. This test points to a co-integration relationship between GDP and the input variables. For each country the Chi-squared value is above the critical value, which implies that the null hypothesis of no co-integration is rejected. The results for co-integration between TFP and the input variables are more mixed across countries. This suggests that we should be cautious in the interpretation of the TFP models, especially for those specified in levels rather than first-differences.

We also perform diagnostic tests on serial correlation, country-level heteroscedasticity and contemporaneous correlation across countries (see “Appendix 2”). We perform these tests for the baseline specifications of the Cobb–Douglas models for GDP and TFP [Eqs. (4) and (6)]. The panel data tests for serial correlation (Wooldridge 2002) do not reject the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation. We test for groupwise (by country) heteroscedasticity in the error terms using a modified Wald statistic (Greene 2000, p. 598). The null hypothesis of homoscedasticity is rejected for GDP and TFP. We test whether error terms are independent across years using the Pesaran test (Pesaran 2004) and the Friedman test. For both GDP and TFP these tests show evidence of contemporaneous correlation.Footnote 20 Because of the results of the different diagnostic tests, we use robust standard errors in all regressions.

6.1 Baseline Results

Table 4 presents the estimation results of the Cobb–Douglas, translog, and augmented production functions. The first four columns concern Cobb–Douglas production functions, using either GDP (columns 1 and 2) or TFP (columns 3 and 4) as dependent variables.Footnote 21 In both models the included R&D variables are either in stocks or in flows. The fifth and sixth columns concern the error-correction model using either GDP or TFP and R&D stock variables. The seventh column presents the results of the translog production function, using GDP as outcome variable and R&D stock variables. The last column shows the augmented production function model, using TFP as the outcome variable and R&D stock variables as covariates. The table only shows the estimated coefficients for public R&D, private R&D, physical capital, and (quality adjusted) labour capital.Footnote 22 Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

The Cobb–Douglas model yields statistically insignificant effects of public R&D on GDP. Formal testing confirms constant returns to scale for physical capital and labour, which validates the models for TFP.Footnote 23 Results for TFP are also insignificant. Point estimates are (slightly) positive in the stock specifications and negative in the flow specifications. The estimates in the stock specification should be interpreted as elasticities. Hence, a 1% increase in public R&D expenditures increases GDP with 0.006%. The estimates in the flow specification should be interpreted as rates of return. The error-correction modelFootnote 24 and translog model show statistically significant negative effects of public R&D. The augmented model, which includes additional production factors, such as public capital, the stock of inward and outward foreign direct investments and the shares of high-tech imports and exports, yields a statistically significant positive effect of public R&D. The estimated elasticity equals 0.04.Footnote 25 The number of observations in this analysis is smaller, since the additional variables are not available in the years before 1981 and not for Greece, Iceland and New Zealand. The estimated impact of private R&D is insignificant in the Cobb–Douglas models and statistically significant and positive in the translog, ECM, and augmented models. For physical capital positive elasticities are found in all models, ranging from 0.18 to 0.60. Note that the estimated coefficients for labour do not equal the labour share in the Cobb–Douglas and ECM models, because we have normalized GDP and capital stock by (quality adjusted) labour.

While the estimated public R&D elasticities vary across models (from significantly negative to significantly positive), most models yield positive elasticities for private R&D, which is in line with the empirical literature (e.g., Hall et al. 2010). Only the Cobb–Douglas models yield statistically insignificant effects for private R&D.

The bottom three rows of Table 4 present the results of several model tests: the log likelihood (LL), the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for model selection. Models with low values of the information criteria are typically preferable. The results show that most of the models are reasonably comparable in terms of model fit. Only the translog model seems to perform better. The information criteria for the augmented model cannot be directly compared to those of the other models, since a different estimation sample has been used. When evaluated on the same sample (from 1981), the augmented model performs equally well as the Cobb–Douglas and ECM model.

6.2 Sensitivity Analyses

We proceed by performing a set of sensitivity tests to probe the robustness of these results. Table 5 presents the estimated effects of public R&D in various types of sensitivity analyses. Each cell represents a separate regression. The columns correspond to the models described in Table 4. Each row corresponds to a separate sensitivity test.

The top panel shows sensitivity tests related to the model specification, such as the exclusion of covariates and the use of different lag structures for the R&D variables. The latter may be important, since it can take years before public R&D investment eventually results in productivity gains. The exclusion of covariates does not importantly affect the results, except for the augmented production function model. Removing private R&D as explanatory variable yields a statistically insignificant effect, while removing public capital yields a statistically significant negative effect of − 0.02. As expected, the inclusion of a single R&D variable that takes into account both public and private R&D yields somewhat more positive results. The estimated elasticities for total R&D stock variables are statistically significant (at a 5 and 10% level) and positive in the Cobb–Douglas models.

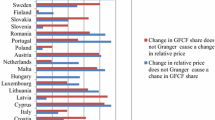

Changes in the lag structure (2- or 10-year lags instead of 1 year) of the R&D variables do not alter the main findings. For the Cobb–Douglas models changes in the lag structure sometimes result in changes in the sign of the coefficient, but estimated coefficients remain insignificant in all cases. For the translog and the augmented model sign and size of the coefficients are similar to the baseline results. For the ECM model, coefficients are similar and significant in the case of 2-year lags, but smaller and insignificant in the case of 10-year lags. Hence, our main findings seem to be quite robust to the inclusion of up to 10-year lagged R&D investments. Especially in the stock specifications we would not have expected large differences, since the constructed stocks are relatively stable over time. The ECM model allows to distinguish between short run and long run effects of public R&D investment. The long run effects are reported in Table 4. The short run effects of public R&D investment on GDP and TFP in the baseline specification are negative and insignificant.Footnote 26 Additionally, we estimate panel VARs for GDP and TFP in the baseline specification to test for Granger Causality. The null hypotheses that public R&D investments does not Granger cause GDP or TFP cannot be rejected (see “Appendix 3” for the results).

The second panel addresses heterogeneity in effects across time periods and countries. The impact of public R&D might have been larger during certain periods or in specific countries. The Cobb–Douglas models yield positive elasticities if we restrict the sample to the 1981–2011 period, one of which is statistically significant at a 5% level. A further restriction to the more recent 1990–2011 period gives all statistically insignificant elasticities. In both periods the translog models and the ECM models for TFP still yield—even more strongly—negative significant effects. The estimated coefficient in the augmented model turns insignificant in the 1990–2011 period. Performing the analyses on a sample of EU27 countries does not alter the main findings, while the inclusion of all available 40 countries yields positive elasticities in the Cobb–Douglas models. Expanding the number of countries is not feasible in the augmented model due to limited data availability. The augmented model shows a statistically insignificant effect when only the EU-27 countries are included. The impact of public R&D may also differ across countries with relatively high and low level of knowledge investments. We split our sample of countries into two groups: countries with a relatively high and a relatively low R&D intensities. Splitting the sample based on the ranking of country’s public R&D intensities yields no clear conclusion on the observed differences. The point estimates for highly R&D intensive countries are lower in most of the Cobb–Douglas models (one of which is significant at the 10% level) and the augmented model, but larger in the translog and ECM models.

The third panel investigates the robustness of the results to different assumptions with respect to the construction of R&D stocks. This concerns both the use of other depreciation and pre-sample growth rates, and the use of different weights for the construction of the foreign R&D stock. Changing the depreciation rate from 15% to either 10 or 20% yields similar results. Also, the use of a single pre-sample growth rate of 5% hardly affects the results. The construction of foreign R&D using weights based on distance measures gives more positive elasticities in the Cobb–Douglas models, one of which is statistically significant. Using weights based on trade flows also yields a significant positive effect in the Cobb–Douglas stock models. The results of the other models are not importantly affected by the use of other weights.

The bottom panel shows the results for other definitions of public R&D. In these analyses the sample is restricted to the period 1981–2002, since the alternative definitions are not available for earlier periods. Changing the definition to all R&D expenditures financed by the government (based on either public budgets or survey information) yields negative elasticities in most models. Only the augmented production function model still shows positive and statistically significant effects. In addition, we have distinguished public R&D into defense-related R&D and civil R&D. Existing evidence suggests that especially defense-related R&D may generate large spillovers to other sectors (e.g., Nelson 1993). The results do not provide evidence of larger productivity effects for defense-related R&D.

In both the translog and augmented models the advantage of a flexible form comes at the risk of overfitting: the models might be estimating residual noise instead of the true relationship between the variables. To prevent this, we have imposed restrictions on the functional form. In the translog model we assume profit- maximizing behaviour in the private sector; in the augmented model we remove non-significant variables using a two-step estimation method. The results might be dependent on the way we define the profit maximizing problem and the criteria we choose to remove non-significant variables (see “Appendix 4”).

Figure 3 provides a summary of the results. We find that the results from estimating Cobb–Douglas production functions are in some cases sensitive to specific assumptions, especially with respect to the sample taken into account, the construction methods for the foreign R&D stock and the use of different definitions of public R&D. Nevertheless, in most analyses we find statistically insignificant effects of public R&D on output. The estimates of the error-correction models seem to be very sensitive. They range from negative (significant) to statistically insignificant estimated coefficients. Especially the models for TFP yield robust negative and significant coefficients. The results of the translog production functions are almost always negative, although the size of the coefficients differs substantially over the sensitivity tests. The augmented production function models show mostly positive and statistically significant effects. These results seem to be sensitive to the inclusion of specific covariates, and the sample taken into account. Both the results of the translog and augmented models are somewhat sensitive to the specific assumptions with respect to the estimation procedure.

Estimated coefficients of public R&D by model. Note Each dot represents a coefficient for a different sensitivity analysis. The order is equal to Table 4

Our set of analyses suggests that differences in the estimated returns to public R&D investments can be mainly attributed to the use of different types of models (rather than to the use of different samples or assumptions within model types). The estimated coefficients vary more widely across models than across samples (time periods or the included set of countries), construction methods or definitions of the included variables. The overall picture that emerges, is that estimates of Cobb–Douglas and translog production functions do not provide evidence for positive returns to investments in public R&D. At the same time, the augmented models generally yield positive results. These findings suggest that it is hard to draw universal conclusions about the effects of public R&D investments on output (growth), but that differences across countries may be important for an efficient use of R&D resources.

6.3 Country Heterogeneity

Table 6 shows the estimated country-specific effects of public R&D in the translog (column 1) and augmented production function model (column 2). Both models allow for country heterogeneity by including interaction terms. The first row presents the average estimated effect across all countries; the next rows present the country-specific coefficients. These country-specific coefficients follow from the estimated coefficients of Eqs. (9) and (11) and are calculated using the average value of the inputs for each country. In line with the general results presented in Tables 4 and 5, all country-specific effects in the translog model are negative and statistically significant. In the augmented model, that includes additional production factors, the estimated effects are positive for most countries. In these models the return to public R&D is more closely related to the national context. In some countries the point estimates are negative. The differences in the estimated impact of public R&D on TFP across countries are driven by the interaction terms. We find country-specific coefficients in a range from -0.02 in the US to 0.14 in Ireland. There are no clear differences between large and small countries. In large countries knowledge spillovers to other countries are less likely, and hence public R&D investments might be more profitable in such countries. The estimated elasticities, however, do not indicate that the returns to public R&D investments are typically higher in large countries.Footnote 27

7 Conclusions and Discussion

This paper investigates the returns to publicly performed R&D investments by means of a cross-country macro-economic analysis. We exploit time series data and use a broad variety of models to assess the impact of public R&D spending on economic growth and productivity. The overall picture that emerges from our production function models is that the estimated returns to public R&D investments are not unambiguously positive. Our set of analyses suggests that differences in the estimated returns to public R&D investments can be mainly attributed to the use of different types of models, rather than to the use of different samples or assumptions within different model types. Our analysis points out that the relationship between publicly performed R&D and economic performance is highly country-specific, and that only models that allow for heterogeneity across countries provide positive and statistically significant estimates of the rates of return.

Most of the estimates based on Cobb–Douglas production functions—including error-correction models—yield statistically insignificant effects. These models take into account public, private and foreign R&D, and the primary production factors. In translog production function models most of the estimated elasticities are negative and statistically significant, something that is at odds with our theoretical hypotheses. These models are based on similar production factors and allow for country heterogeneity by including interaction terms, but make much stronger assumptions on fully rational behaviour of the (private) actors involved in STI. Models that include additional variables (public capital, the stock of inward and outward foreign direct investments and the share of high-tech imports and exports) and allow for country heterogeneity show mostly positive effects. In these models the return to public R&D investments is more strongly related to the national context.

A number of remarks is in place with respect to the interpretation of the results. First, the results concern marginal effects that apply to (small) adjustments compared to the observed investment levels. Hence, non-positive and non-significant coefficients do not imply that previous investments had not improved economic performance. Second, the empirical analysis is limited to economic outcomes. The societal value of scientific research is broader than its economic value in terms of growth or productivity. A large fraction of public R&D spending is not specifically targeted at direct productivity improvement. Medical research, for example, can enhance health outcomes without directly affecting economic growth. In addition, much of the basic research performed at universities and public institutions is at best only indirectly related to long run economic growth.

It is difficult to identify the economic return to public R&D by macro-economic approaches. Scientific research is not a homogeneous good as public R&D investments can apply to different research fields and different types of research (varying from more basic to more applied work). Its relationship with economic growth is indirect and long term, and the underlying mechanism involves many complex interactions with other relevant actors in the innovation system. Analyses at the macro-economic level focus directly on the impact of science on economic growth and hence provide (almost by definition) only limited insights into the relevant underlying processes. In addition, the limited variation in the levels of public R&D spending over time and the strong correlation with other production factors compromise the empirical analyses.

Our findings suggest that spending on public R&D does not yield an automatic return in terms of economic or productivity growth. The return seems to be dependent on the national context, in which institutions and government policies play an important role. Hence, rather than evaluating what the absolute monetary value of public investments in R&D is, it would be helpful to know more about optimal ways of spending public funds. Micro-economic evaluations can provide insights into the effectiveness of specific institutions or science policy measures and learn how the value of science can be improved. But such micro studies are also, by their very nature, often focused on a narrow context that makes it difficult to capture the full effects of public R&D. Therefore, studying knowledge networks is of interest too because of the importance of spillovers for the economic impact of public efforts to foster economic development. Future research along these lines is likely to contribute to unravelling the ‘black box’ of the economic value of public investments in science, technology and innovation.

Notes

In the period 2010–2013 (most recent data available), the joint share of the government and higher education sector in total R&D expenditures in the OECD area fell from 30.9 to 28.9 percent (OECD 2014).

Because of data considerations we focus on publicly performed instead of publicly funded R&D in this paper (see the data section below for details).

The Cobb–Douglas functions are also estimated in an error-correction model framework.

The presented estimates in the translog and augmented models concern average elasticities across all countries.

Foreign R&D capital includes both foreign private and foreign public R&D.

The literature on innovation systems argues that innovation is a collective process, in which many actors are involved, and that this process can be characterized by very different rates of return under different circumstances. The essence of this literature is that the complexity of the relationships between the various actors in the innovation “system”, as well as the highly uncertain nature of the innovation process, make it impossible for the actors in the system to behave in a fully rational way.

Throughout the paper, when we use the terms ‘heterogeneity across countries’ we mean heterogeneity that is caused by differences in the inputs across countries. In this sense, models that include interaction terms allow for heterogeneity across countries. We do not mean that the estimated coefficients can vary across countries.

This dataset was constructed by merging the publicly available MSTI data from 1981 to older files stored in the archives of UNU-MERIT.

We choose this definition (based on publicly performed research) because of better data availability. Other definitions of public R&D (based on government financed research, such as GBAORD and GovFinGERD) are used in robustness analyses. Both types of variables are strongly correlated. See the Frascati Manual and MSTI guideline for more information on the data collection and definitions.

We choose to use PWT because it contains economic data for a larger set of variables and countries compared to MSTI.

The total number of observations in the analyses including those additional variables equals 584.

We obtain data on the number of migrants between countries from the World Bank. This method requires a balanced set of R&D expenditures for all countries over time (otherwise foreign R&D stock would increase over time by construction due to an increasing number of countries for which R&D expenditures are available in the data). Hence, for the purpose of constructing foreign knowledge stock we linearly extrapolated all R&D expenditure data back to 1963.

We have used bilateral export information from 1963 onwards from the UN-COMTRADE database. Other studies have also used weights based on patent matrices or trade flows. The empirical evidence on the importance of trade flows as a channel of R&D spillovers seems to be mixed (e.g., Lichtenberg and Van Pottelsberghe 1998; Keller 1998). We use migration flows in our main analysis because of better data availability.

A twice as high human capital index should be interpreted as a twice as high productivity.

This implies that we assume a country-specific exponential trend. The inclusion of country fixed-effects in the model induces a bias in the parameter estimates (Nickell 1981), but as our panel is relatively long this bias will in all likelihood be small.

We use here that \(\tau \Delta kc_{t}^{G} = \frac{{\partial Y_{t} }}{{\partial KC_{t}^{G} }}\frac{{KC_{t}^{G} }}{{Y_{t} }}\quad \Delta kc_{t}^{G} = \rho \frac{{KC_{t}^{G} }}{{Y_{t} }}\quad \Delta kc_{t}^{G} \approx \rho \frac{{KC_{t}^{G} }}{{Y_{t} }}\frac{{\Delta KC_{t}^{G} }}{{KC_{t - 1}^{G} }}\). When \(\Delta KC_{t}^{G}\) is relatively stable over time, the last term reduces to \(\rho \frac{{\Delta KC_{t}^{G} }}{{Y_{t} }}\). Instead of assuming that δ is small, we can also replace \(\Delta KC_{t}^{G}\) by \(R_{it}\) when \(\frac{{KC_{i,t - 2}^{G} }}{{Y_{i,t - 2} }}\) is stable. In that case, \(\rho \frac{{\Delta KC_{i,t - 1}^{G} }}{{Y_{i,t - 1} }} = \rho \frac{{R_{i,t - 1}^{G} }}{{Y_{i,t - 1} }} - \rho \frac{{\delta KC_{i,t - 2}^{G} }}{{Y_{i,t - 2} }}\), where the last term is a constant. This constant disappears into the error term.

When the variables are not co-integrated, the ECM might pick up spurious correlation between the levels of Y and the inputs. We perform a co-integration test in “Appendix 1”.

An alternative to this specification is the pooled mean-group model. In this model the short run effects are allowed to differ across countries while the long run effects are restricted to be equal. See footnote 24 for results of this alternative specification for the baseline sample.

Rental prices for private R&D capital and fixed capital are assumed to be equal to the a price index (respectively the price level of the capital stock and the GDP price deflator) multiplied by a depreciation rate (respectively 0.15 for knowledge capital and 0.1 for physical capital) plus an interest rate equal to 0.05. The labour share of income is taken directly taken from PWT (share of labour compensation in GDP at current national prices).

When we perform the tests on the Cobb–Douglas models without including year dummies all tests reject the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence with p values of 0. Results are somewhat more mixed when we include year dummies.

These variables are normalized by quality-adjusted labour (see Sect. 4.1).

In the augmented model the labour coefficient represents the estimated coefficient of h. The full table of estimation results is available upon request.

We test this by estimating the model \(\Delta y_{it} = \Delta \omega_{t} + \alpha \Delta k_{it} + \beta \Delta lh_{it} + \varepsilon_{it}\) and then test whether \(\alpha + \beta = 1\).

The pooled mean-group specification of the ECM model gives a non-significant long run effect of public R&D investment on GDP (− .015, SD = .014) and a significant negative effect on TFP (− .176, SD = .022).

This is the result of the model that includes interaction terms. Inclusion of the additional production factors without adding interaction terms yields a statistically insignificant effect of public R&D (− .009).

− .038 (.026) for GDP and − .024 (.023) for TFP.

When we perform the tests on the Cobb–Douglas models without including year dummies all tests reject the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence with p values of 0. Results are somewhat more mixed when we include year dummies.

References

Abramovitz, M. A. (1956). Resource and output trends in the United States since 1870. American Economic Review, 46(2), 5–23.

Abrigo, M. R. & Love, I. (2015). Estimation of panel vector autoregression in Stata: A package of programs. http://paneldataconference2015.ceu.hu/Program/Michael-Abrigo.pdf.

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351.

Bartelsman, E. J. (1990). R&D spending and manufacturing productivity: An empirical analysis. Working paper, Division of Research and Statistics, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Bassanini, A., Scarpetta, S., & Hemmings, P. (2001). Economic growth: The role of policies and institutions: Panel data. Evidence from OECD countries. OECD Economics Department working papers no. 283, Paris: OECD.

Becker, B. (2015). Public R&D policies and private R&D investment: A survey of the empirical evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(5), 917–942.

Boswijk, H. P. (1994). Testing for an unstable root in conditional and structural error correction models. Journal of Econometrics, 63(1), 37–60.

Brown, J. R., Martinsson, G., & Petersen, B. (2012). Do financing constraints matter for R&D? European Economic Review, 56(8), 1512–1529.

Christensen, L. R., Jorgenson, D. W., & Lau, L. J. (1973). Transcendental logarithmic production frontiers. Review of Economics and Statistics, 55(1), 29–45.

Coe, D., & Helpman, E. (1995). International R&D spillovers. European Economic Review, 39(5), 859–887.

Coe, D., Helpman, E., & Hoffmaister, A. (2009). International R&D spillovers and institutions. European Economic Review, 53(7), 723–741.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152.

Dimos, C., & Pugh, G. (2016). The effectiveness of R&D subsidies: A meta-regression analysis of the evaluation literature. Research Policy, 45(4), 797–815.

Engelbrecht, H.-J. (1997). International R&D spillovers, human capital and productivity in OECD economies: An empirical investigation. European Economic Review, 41(8), 1479–1488.

Fagerberg, J. (1988). International competitiveness. Economic Journal, 98(391), 355–374.

Freeman, C. (1995). The national system of innovation in historical perspective. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19(1), 5–24.

Freeman, C., Clark, J., & Soete, L. (Eds.). (1982). Unemployment and technical innovation: A study of long waves and economic development. London: Frances Pinter.

Gheorghiou, L. (2015). RISE brief on value of research. Note prepared for the RISE expert group to the European Commission, Mimeo.

Greene, W. (2000). Econometric analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Griliches, Z. (1979). Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity growth. Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 92–116.

Griliches, Z. (1998). R&D and productivity: The econometric evidence. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Griliches, Z., & Lichtenberg, F. (1984). Interindustry technology flows and productivity growth: A re-examination. Review of Economics and Statistics, 66(2), 324–329.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Guellec, D., & van Pottelsberghe, B. (2004). From R&D to productivity growth: Do the institutional settings and the source of funds matter? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 66(3), 353–378.

Hall, B., Mairesse, J., & Mohnen, P. (2010). Measuring the returns to R&D. In B. H. Hall & N. Rosenberg (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of innovation (pp. 1033–1082). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Haskel, J., & Wallis, G. (2013). Public support for innovation, intangible investment and productivity growth in the UK market sector. Economics Letters, 119(2), 195–198.

Jones, C. I. (1998). Introduction to economic growth. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Jones, C. I. (2002). Sources of U.S. economic growth in a world of ideas. American Economic Review, 92(1), 220–239.

Kaldor, N. (1957). A model of economic growth. Economic Journal, 67(268), 591–624.

Keller, W. (1998). Are international R&D spillovers trade-related? Analyzing spillovers among randomly matched trade partners. European Economic Review, 42(8), 1469–1481.

Khan, M., & Luintel, K. B. (2006). Sources of knowledge and productivity: How robust is the relationship? OECD Science, Technology and Industry working papers no. 2006/06. Paris: OECD.

Kuznets, S. (1966). Modern economic growth: Rate, structure, and spread. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lichtenberg, F. (1993). R&D investment and international productivity differences. In H. Siebert (Ed.), Economic growth in the world economy (pp. 47–68). Tubingen: Mohr.

Lichtenberg, F., & van Pottelsberghe, B. (1998). International R&D spillovers: A comment. European Economic Review, 42(8), 1483–1491.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.