Abstract

International students who pursue their academic goals in United States are prone to difficulties when attempting to build social resources and adjust to the new culture. Social media is a practical means of connection due to its ease of use and accessibility. Previous research has indicated contradictory effects of social media use on academic engagement. In addition to the direct effect, this research examined social media use influences on international students’ learning engagement by mediating social capital and cultural adjustment. A total of 209 international students completed a web-based survey distributed via e-mail and social media between November 2021 and May 2022. Data were analyzed using Structural Equation Model. Results showed that only purposely using social media to collaborate with learning counterparts or materials directly improves international students’ learning engagement. Other uses of social media (e.g., expanding new resources, solidifying close relationships) have no significant direct effects. Nonetheless, they are essential to improving levels of learning engagement via the mediation of bridging capital (social resources attributed to expanding relationships) and students’ cultural adjustment in the U.S. International students’ bonding capital (social resources available through trustworthy relationships) and home cultural retention showed little direct or indirect effects on learning engagement. This study recognizes the importance of social resources and cultural adjustment for international students. Also, this study provides valuable information to educators and administrators, as there is a need to identify the underlying mechanisms to contribute feasible learning intervention approaches and alleviate negative effects for international students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the U.S., international students comprise approximately 5% of the student population in higher education (Institute of International Education, 2021). Some challenges associated with studying abroad include students leaving their family and friends, learning in a non-native language, and adjusting to a different culture. The ongoing threat of the global COVID-19 pandemic contributed to these difficulties, making it harder for international students to maintain regular connections with instructors and other students and effectively cope with their academic challenges (Kim & Hogge, 2021; Tsai et al., 2020). Therefore, international students are experiencing unprecedented rates of social isolation, psychological stress, cultural conflict (Tsai et al., 2020), and academic difficulty (Jordan & Hartocollis, 2020; Tsai et al., 2020).

International students are encouraged to increase their social resources to alleviate stress and to get acclimated to their host countries, promoting both mental health and academic success (Brunsting et al., 2018; Chai et al., 2020, 2022; Cruwys et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). Just as social media platforms (e.g., YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok) have become popular among many people between the ages of 18 and 29 living in the U.S., they have also become integral in the lives of college students (Blasco-Arcas et al., 2013; Cao & Tian, 2022; Chang et al., 2019; Stathopoulou et al., 2019). Due to the popularity of and easy access to social media (Yu et al., 2019), it attracts sojourners such as international students to utilize various applications to achieve multiple communication and entertainment goals (Ali-Hassan et al., 2015).

Although there is an increase in researchers exploring the complicated effects of social media usage on learning engagement in higher education, there are many contradictory conclusions regarding the effects social media has on learning engagement (Ansari & Khan, 2020; Cao & Tian, 2020; Chawinga, 2017). One possible reason of the contradictory effects derives from social media’s broad range of applications. A single social media platform can support communication and relaxation, with no need to shift to another platform; this same platform may also enable users’ access to academic courses or allow them to follow experts in a particular field (Ali-Hassan et al., 2015). YouTube is one such platform as it allows users to watch videos for entertainment, learn instructional tutorials, or even access academic courses, depending on the users’ goals and context (Moghavvemi et al., 2018).

Additionally, even in the context of intentionally using social media for learning, the influence of time spent on social media on academic performance is unclear. In higher education, some instructors integrate social media platforms with information communication technology (ICT) or learning management systems (LMS), effectively strengthening peer-to-peer discussion, instructor interaction, and the sharing of course-related materials (Al-Rahmi et al., 2018; Ansari & Khan, 2020). The joint efforts among students or students with instructors facilitate collaborative learning approaches (Roberts, 2005), promote learning attitudes (Kabilan et al., 2010), engage with materials and counterparts, and improve student performance (Al-Rahmi et al., 2018). However, these positive results are investigated through collaborative learning, in which social media is one of the integrated approaches to enhance discussion or content sharing (Al-Rahmi et al., 2018; Cao & Tian, 2022; Chawinga, 2017). On the other hand, social media is often associated with negative effects. College students who excessively and unconsciously consume social media reduce their hours of engagement with learning materials. Moreover, social media applications are misused in the classroom (Tindell & Bohlander, 2012) and other learning contexts distracts attention span (Ansari & Khan, 2020).

The inconsistent results of social media use on learning engagement among general college students invoke further studies. These studies should investigate how international students utilize social media to achieve academic success. International students’ resources for expanding relationships are substantially limited compared to domestic students. Social media provides easy access and various choices that allow international students to set up global and local communication applications on their devices. In addition to expanding new circles in the U.S., international students can also use their native language to communicate with families and friends at home. As expounded in the following literature review, international students leverage social media to manage their networking on and off campus, implicating their willingness and competence in coping with some of the challenges they face in the U.S.

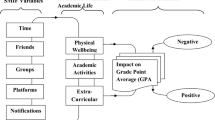

The findings of this study will potentially contribute theoretical and practical implications to improve international students’ adjustment and academic success. Theoretically, this study examines social media’s direct and indirect impact on international students’ learning engagement. The conceptual model used (Fig. 1) brings two additional factors, cultural adjustment, and social capital, as mediators to demonstrate how these mediators complicate the indirect effects. Practically, findings from this study should provide valuable information to educators and administrators, as there is a need to identify the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the feasible learning intervention approaches to alleviate negative effects for international students.

1 Literature review

The literature reviewed for the current study is related to (1) college students’ learning engagement and its complexities, (2) the way social media usages inconsistently affect college students’ learning engagement in different contexts, and (3) the way social capital and culture adjustment influence on learning engagement. Following each topic, we discussed our hypothesis model and depicted the direct and mediated conceptual model, as shown in Fig. 1.

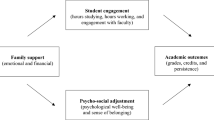

2 College student learning engagement

Student engagement is conceptualized as the effort of students’ participation in academic work, involvement in the learning process, and achievement of expected outcomes (Handelsman et al., 2005). Scholars have widely agreed that student learning engagement is a comprehensive construct that comprises behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement dimensions (Fredricks et al., 2004). The direct observation of behavioral engagement refers to students’ classroom tasks or coursework involvement, which can be easily identified through indicators/markers (Finn & Zimmer, 2012). Affective engagement refers to emotions, either contentment or stress, generated by students’ interactions with school/course work or people encountered (Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). Cognitive engagement refers to students determining motivational goals, mastery orientation, and imposing self-regulation and learning strategies (Cleary & Zimmerman, 2012). The absence of student engagement is seen in burnout, withdrawal, and a lack of motivation, all of which lead to academic failure (Finn & Zimmer, 2012; Skinner, 2016).

According to Skinner (2016), two distinct facilitators, self and context, help students stay engaged. The self characterizes internal features, such as self-perception, personality traits, or a sense of belonging, to motivate intentional actions (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Goodenow, 1993); context broadly refers to the external or social factors and influences from the student’s environment (Tyson & Hill, 2009), presented as relatedness (e.g., family, schools, peers) so that the individual feels supported.

International students’ learning engagement, both in self and context, is constantly interwoven with challenges of coping with language competence in specific (Moon et al., 2020), or new environments, which are cross-cultural in general (Al-Oraibi et al., 2022; Chai et al., 2020; Humphrey & Forbes-Mewett, 2021). Moon et al. (2020) explored the challenges in lectures, class discussions, and writing assignments among international students from Korea and China. The result shows that besides language barriers, relationships with instructors and understanding of the assessment standards are essential to differentiate their study experiences. As the explication of the context factor, the feeling of being supported by family, institution, and community positively contributes to academic engagement and achievement. International students being remote to their strong support at home indues the self-perceived social losses (Humphrey & Forbes-Mewett, 2021). Chai et al. (2022) conducted an international students’ study in Japan, suggesting the perceived lack of personal resources leads to mental and physical drain. In contrast, sufficient social resources alleviate negative emotions, advancing academic engagement. Moreover, a sense of inclusion instead of being viewed as “others” encourages international students to participate in peer group discussions and interact with instructors (Blackmore et al., 2021; Chai et al., 2020; Tran & Pham, 2016).

3 The effects of social media on college student learning engagement

International students, like many college students in the U.S., grew up in a technologically rich world (Kunka, 2020), and they habitually use social media for various purposes that range from academic tasks to personal communication. Social media is a platform that incorporates international students’ resources to build self and context to engage with students, instructors, and organizations in the U.S. while connecting to family and friends in their home countries (Cao & Tian, 2022; Chang et al., 2019). However, there is rising sentiment against excessive yet passive social media consumption as it is detrimental to academic engagement. College students constantly access social media while studying (Flanigan & Babchuk, 2015). Tindell and Bohlander (2012) found that 92% of undergraduate students who participated in the survey self-reported using their mobile phones to access information unrelated to course materials and texting messages in class. Many college students lack the ability to avoid being distracted by social media. As Flanigan and Kiewra (2018) found, individuals may skillfully enjoy personal communication, gaming, or other entertainment, but they cannot strategically leverage these capabilities in an educational environment.

Some scholars have explored ways to facilitate learning while factoring in social media’s notable accessibility and popularity among college students. Drawing from an affordance theory perspective (Gibson, 1986), some researchers describe the use of social media in education as the interaction between actors (users) and artifacts (social media applications) to satisfy needs or achieve goals (Hutchby, 2001; Pozzi, 2014). As a single social media application engages a wide range of users and vice versa, individuals fulfill various tasks without shifting to another social media application. Like YouTube, Twitter, a mini-blog platform, allows students to discuss course topics, complete assignments, and share materials. Chawinga (2017) designed an experimental course at a public university in Malawi that required students to interact with each other and share learning materials via Twitter and blogs using a predefined hashtag. Using Twitter advocated ‘learner-centred’ [sic] pedagogical approach and facilitated cognitive learning engagement with peers and course materials.

Instead of singling out an individual application, we treat social media as an assembly with a range of choices (Ali-Hassan et al., 2015; Ansari & Khan, 2020; Cao & Tian, 2022) and focus on the individual purposes and tasks it affords. International students set up various social media choices ranging from globally popular applications to regionally based ones on their mobile devices (Cao & Meng, 2020; Tu, 2018; Yu et al., 2019) to accomplish their tasks. From the technological lens of affordance theory, Ali-Hassan et al. (2015) proposed a three-dimensional (i.e., social, cognitive, hedonic) used to determine the direct and indirect influence of social media on corporate job performance. In the current research, the social dimension is further divided into two subdimensions, to expand future networks (new) and interact with pre-existing relationships (close) to align with international students’ social goals. The following four hypotheses were developed based on the four social media use dimensions (Fig. 2).

H1a: International students using social media to expand new resources positively affect learning engagement.

H1b: International students using social media to maintain close relationships with family and friends positively affect learning engagement.

H1c: International students using social media in a cognitively oriented way to build academic collaborations positively affect learning engagement.

H1d: International students using social media to consume hedonic content negatively affect learning engagement.

4 The mediator effect of cultural adjustment and social capital

4.1 Cultural adjustment

For international students, acclimatization to their new environments (e.g., host culture, new institution, new community) helps them cope with feelings of loneliness (Russell et al., 2010; Sawir et al., 2008) or strengthen their sense of belonging (Glass et al., 2015; Tu, 2018; Van Horne et al., 2018). Kim (1988) proposed the Integrative Theory of Cross-Cultural Adaptation that structures the process of engaging in social communication and identity transformation among sojourners, which refers to the individual who grew up in one primary culture and later relocated to the host culture. This multidimensional theory describes the aspects that influence cross-cultural adaptation, such as personal predisposition (e.g., ethnic proximity), host environment (e.g., host conformity pressure), and intercultural transformation (e.g., intercultural identity). In research aimed at international students in the U.S., Kim and her colleagues found that Asian students show lower host communication competence than European students, resulting from insufficient knowledge of host culture and less involvement in intercultural activities (Kim, 2001; Kim et al., 2016). Moreover, sense of belonging is also a factor that influence international students’ adaption in the U.S. According to Van Horne et al. (2018), international students consistently reported lower levels of satisfaction and a weaker sense of belonging than their American counterparts across nine universities in the U.S. On the contrary, those international students reporting a stronger sense of belonging had more interactions with students from other cultures, although the frequency of this interaction varied largely (Van Horne et al. 2018). In this respect, many researchers have reached similar conclusions: international students’ cultural adjustment correlated to their level of engagement with domestic students (Glass & Westmont, 2014), participation in diversity-related cocurricular activities (Glass & Westmont, 2014), and interactions with instructors (Glass et al., 2015; Stathopoulou et al., 2019).

In addition to adjusting to the host culture, international students’ retention of their home culture is also important to their cultural integration (Berry et al., 2006; Demes & Geeraert, 2014). Individuals ranking high in both host-culture adjustment and home-culture retention, defined as cultural integration, demonstrated better cultural adjustment in foreign countries (Demes & Geeraert, 2014). Using a sample of 12 international students in the U.S., Tu (2018) investigated their preferred language and tasks using different social media platforms. Students use of their native language to maintain connections with family at home or friends from similar cultures and enjoying entertainment can lower their stress levels (Tu, 2018). Nevertheless, using English on social media is often associated with expanding one’s social circle, engaging in academic tasks, and adjusting to the U.S. This finding can be explained by the affordance perspective (Gibson, 1986) that international students take actions based on social media features that are available to everyone. They can accomplish different tasks driven by their unique emotional needs and academic goals. However, there is limited knowledge of the international students’ uses of social media and its association with cultural integration and learning engagement.

We hypothesize that the host or home cultural factors mediate different social media uses influencing their learning engagement (Fig. 2).

H2a: International students using social media to expand new social resources will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating host cultural adjustment.

H2b: International students using social media to maintain close relationships with family and friends will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating home cultural adjustment.

H2c: International students using social media in a cognitively oriented way to build academic collaborations will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating host cultural adjustment.

H2d: International students using social media to consume hedonic content will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating home cultural adjustment.

4.2 Social capital theory

Social capital is conceptualized as the outcome of interpersonal networks and the benefits that are empowered by the relationships integrated online and offline (Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 2000). Bridging and bonding are two distinct components that collectively gauge the amount of social capital. While bridging capital is associated with weak ties that expand connection and spread information to a broader network, bonding offers emotional support and security via the strong ties of relationships (Lin et al., 2012; Putnam, 2000; Tu, 2018).

International students’ social capital is essential to their cultural adjustment and the ways they cope with academic challenges. Social capital enables international students to exchange and acquire new information, provides them with support, and strengthens their sense of belonging (Glass & Westmont, 2014; Phua & Jin, 2011; Williams, 2006). Additionally, social capital enhances international students’ engagement at the colleges and universities they attend (Mbawuni & Nimako, 2015) and in the communities in which they live (Glass & Gesing, 2018). Once international students are in a drastically different cultural environment, they must deal with life difficulties and engage with academic work simultaneously; the psychological and sociological stress caused by insufficient resources impedes their cultural adjustment and academic engagement (Cho & Yu, 2015; Chai et al., 2022).

International students accumulate social capital by building and maintaining relationships with others in the host countries and in their home countries, respectively (Cao & Meng, 2020; Li & Chen, 2014). According to Glass and Gesing (2018), international students’ relationships fit into the four primary networks: academic programs, campus organizations, residential communities, and family and friends. The first three networks are new to the student and must be established in the U.S., and the latter are usually pre-existing. Social media allows integration of the four primary networks, advancing students’ virtual membership into networks that are beyond their physical reach (Phua & Jin, 2011; Wellman et al., 2001). Repeated social interactions, such as attending classes, joining study groups, and participating in student organizations and residential gatherings, strengthen international students’ sense of belonging (Gomes et al., 2015). Moreover, international students’ participation in such activities increases their chances to interact with students from other cultures as well as people from the local community, offering these students more extensive, dynamic social networks and leading to some students having more social capital than others (Glass & Gesing, 2018).

Some researchers found that the process by which international students build bridging and bonding capital is distinct (Cao & Meng, 2020; Lin et al., 2012; Phua & Jin, 2011). Bridging capital results from the development of weak ties (Glass & Gesing, 2018) with new relationships on- or off-campus, access to valuable information, or membership in a professional organization. Meanwhile, bonding capital is the result of strong ties gained through secure and trustworthy pre-existing relationships with family and friends, often from an international student’s home country (Lin et al., 2012). Social capital measures the outcomes that bridging and bonding capital are accumulated in both online and offline contexts (Cao & Meng, 2020; Lin et al., 2012; Phua & Jin, 2011). Online networking increases both bridging and bonding capital while international students stay in the U.S. However, previous studies of social capital suggest that the accumulation of bridging and bonding are imbalanced. The time that international students spend online is associated with bridging capital more than bonding capital. More times of social media use increases bridging capital, but it does not have an equivalent effect on bonding (Lin et al., 2012; Phua & Jin, 2011; Stefanone et al., 2011). The more frequently international students interact with American students, the more their bridging capital is detected, arising from better coping and adjustment to college (Lin et al., 2012).

In the current research, we hypothesize that social capital is a mediator between social media uses and students’ learning engagement. In Ali-Hassan et al. (2015)’s research, social capital demonstrated a “nuanced facet” (p. 78) that social media use positively increases job performance only if the specific use increases social capital. In addition to earlier direct effect hypotheses, we proposed that international students’ social media use will indirectly affect their learning engagement through social capital (Fig. 2).

H3a: International students using social media to expand new social resources will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating bridging capital.

H3b: International students using social media to maintain close relationships with family and friends will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating bridging capital.

H3c: International students using social media to maintain close relationships with family and friends will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating bonding capital.

H3d: International students using social in a cognitively oriented way to build academic collaborations will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating bridging capital.

Lastly, we explored the paths, including cultural adjustment and social capital, to detect the chain mediation effect (Fig. 2).

H4a: International students using social media to expand new social resources will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating host cultural adjustment and bridging capital.

H4b: International students using social media to maintain close relationships with family and friends will indirectly and positively influence learning engagement by mediating host cultural adjustment and bridging capital.

Hypothesis Model

Note: A hypothesis model with direct and indirect paths is shown in the figure. There are four types of social media use (e.g., new, close, cognitive, hedonic), two types of cultural adjustment (e.g., host, home), and two types of social capital (e.g., bridging, bonding), direct and indirect influence the latent dependent variable learning engagement. Each number in the hypothesis model is explained.

5 Method

5.1 Methodology

A quantitative survey research method was utilized to investigate a hypothesized model (Fig. 2) that drawn on the relationships between the different uses of social media, bridging and bonding capital, students’ cultural adjustment to their host and home countries, and learning engagement among international students at a university in the U.S. (Dillman, 2014). This study received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.

6 Participants

The sampling procedure followed a purposeful sampling strategy that targeted eligible international students in higher education in the U.S. A total of 209 participants completed the survey, and all participants were international students enrolled at different colleges throughout the U.S. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 years to 49 years, with a mean average of 28.8 years (SD = 6.5). Among the 209 participants, 42.3% were women (n = 88), and 56.7% were men (n = 118); the remaining 3 students indicated that they “prefer not to say.” Of the students who participated, 46.9% (n = 98) were Asian while 29.7% (n = 62) of the students identified themselves as White, 10% (n = 21) were Black. 8.1% (n = 17) claimed their ethnicity as Hispanic, and 4 indicated that they were “Other.” Most of the students (77.5%, n = 162) reported that they were STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) majors. Of the 209 participants, 38.2% (n = 80) were enrolled in undergraduate degree programs, 32.1% (n = 67) were pursuing master’s degrees, and 29.7% (n = 62) were enrolled in doctoral programs.

7 Instruments

Learning Engagement. Handelsman et al. (2005) developed a college student course engagement questionnaire (SCEQ) measurement. In the current study, we included 16 of 23 items with the factor loading higher than 0.5, measure the individual level of coursework engagement: skills engagement (n = 8, sample item: “Making sure to study on a regular basis”); emotional engagement (n = 3, sample item: “Finding ways to make the course interesting to me”); and participation engagement (n = 5, sample item: “Participating actively in small-group discussions”). Participants were asked to rate each item on a scale of 1 to 5 to indicate the extent to which the learning behavior was applicable to them. On this scale, 1 = not at all characteristic of me to 5 = very characteristic of me. The higher score indicates higher learning engagement. The internal consistency Cronbach’s α for the skills, emotional, and participation engagement subscales was 0.92, 0.81, 0.79, respectively.

Social Media Usage. For this study, we adapted 18 items from Ali-Hassan et al.’s (2015) questionnaire measuring social media use and defined 4 subscales in the current research. The subscales featured the use of social media for (1) expanding new social relationships, (2) solidifying existing close relationships, (3) cognitive learning, and (4) hedonic usage for entertainment. A 5-point Likert-type scale was used to describe the frequency of social media use for a particular purpose, with 1 = Never to 5 = Always. Item samples, such as “I use social media to discover people with interests similar to mine” were designed for social media for new networks (n = 5); “I use social media to create content in collaboration with fellow researchers” for social media cognitive (n = 6); and “I enjoy my break during research work,” for social media hedonic (n = 3). An additional item was added to the social media close scale (n = 3) to distinguish two items: one measured close relation in the U.S., and the other specified the close relations from their home countries. Wording was altered for several items, and two items were added to the cognitive use subscale to describe higher education’s academic and research tasks in the U.S. (sample item: I communicate with people who are in leadership roles in my academic/professional field). The higher score indicates more frequent the particular social media use. The internal consistency Cronbach’s α for the four subscales was 0.80, 0.68, 0.90, 0.72, respectively.

Social Capital. Williams (2006) developed and validated the online/offline bonding and bridging capital measurement. Some scholars have suggested that the social capital obtained from both online and offline contexts associated with social media use are inseparable because social media integrates online and offline relations (Cao & Meng, 2020). In this study, the source of the two social capitals were derived from online usage (social media), which integrates both online and offline networks. Moreover, general interest in this study was in bonding and bridging capital; therefore, the wording “online/offline” was not specified for each survey question. Participants responded to 10 items each to rate their levels of agreement on a 5-point Likert-type scale by 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) to indicate how often each event occurs to measure bonding and bridging capital. An example of an item on the bonding scale is, “There is someone I can turn to for advice about making very important decisions,” while an example from the bridging scale is, “Interacting with people makes me feel connected to the bigger picture.” A higher mean score indicates a higher social capital value. The internal consistency Cronbach’s α value was at 0.91 and at 0.80 for bridging and bonding, respectively.

Cultural Adjustment. The Brief Acculturation Orientation Scale (BAOS), a two-dimensional construct developed by Demes and Geeraert (2014), was used to measure the value of an individual in a host country maintaining the cultural heritage from his or her home country while integrating into the dominant host culture. There were four items for each type of cultural adjustment (i.e., host and home) as aligned with Berry et al. (2006). Participants were asked to indicate their levels of agreement or disagreement on each of the 8 items, with 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. On the home cultural adjustment subscale, participants answered questions such as “It is important for me to have friends in my home country.” Likewise, on the host cultural adjustment subscale, a sample question includes, “It is important for me to have friends in the U.S.” The higher score indicates higher cultural adjustment. The Cronbach’s α value of internal consistency was at 0.80 for the host culture and 0.70 for the home culture.

8 Procedure

An anonymous online survey hosted by the Qualtrics platform collected data that measured variables and participants’ demographic information from November 2021 to May 2022. International students enrolled at a university in the southeastern region of the U.S. were invited to participate in the study and directed to the online survey via an e-mail list sent from the Office of International at a large Southeastern university. An invitation link was also posted by the social media account of the Journal of International Students. Participants were encouraged to forward the survey link to other international students currently enrolled at higher education institutions in the U.S. Once participants clicked the link to access the survey, they were directed to a page allowing them to grant informed consent, and they were required to click “yes” in response to a screening question to identify whether they were international students. A follow-up reminder e-mail was also sent to the students on this e-mail list, and the social media invitation to participate was reposted after the initial invitation.

8.1 Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 28 and Mplus version 8 (Muthen & Muthen, 2017). The SPSS 28 program was used to provide descriptive statistics, correlations, and the reliability of each subscale to summarize the characteristics. The Mplus version 8 was used to examine whether or not the hypothesis model (Fig. 2) for four different types of social media use by international students directly or indirectly influenced their learning engagement by a structural equation model (SEM) path analysis (Hair et al., 2006). To examine the hypothesized model, we applied the equal-weighted composite score variables, the four types of social media use (exogenous variables), the two types of social capital, and the two types of cultural adjustment (endogenous variables), to influence the learning engagement (the latent dependent variable) simultaneously. Deng and Yuan (2022) compared various models using weighted and unweighted path analysis, path analysis with latent variables, and covariance-based SEM. Results suggest that path and partial path analysis are reliable for detecting models.

Investigating the social capital or cultural adjustment’s mediator role was essential in elucidating how the social and cultural factors influence the effect of social media usage on learning engagement. The following model fit indices, such as the Chi-square goodness of fit test, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), were used to evaluate the hypothesis model. According to Hair et al. (2006), the general cut-off value for the indices for CFI and TLI should be above 0.95, and the value of RMSEA should be no greater than 0.1. A significant model evaluation result indicates a poor model fit. Therefore, the inadequate model was improved by trimming insignificant paths (Hox & Bechger, 1998).

9 Results

Descriptive statistics, the internal consistency reliability of Cronbach’s α, and bivariate correlation coefficients (Berk et al., 1996) of the 11 subscales were summarized in Table 1. Cronbach’s α internal consistency and number of items for those 11 subscales were as follows: skills 0.92 (8 items), emotional 0.81 (3 items), and participation 0.79 (8 items), new 0.80 (5 items), close 0.68 (3 items), cognitive 0.90 (6 items), hedonic 0.72 (3 items), bridging (10 items), bonding 0.80 (10 items), host 0.80 (4 items), home 0.70 (4 items). All values of Cronbach’s α demonstrated adequate reliability in this sample except the close subscale was lower than 0.70 (Berk et al., 1996). The subscales were positively significantly correlated to each other at a moderate to large degree (r = .21 ~ .74, ps < 0.01). All four types of social media use have moderate correlation coefficients with three engagement subscales (0.21 ~ 0.48, ps < 0.01). Both bridging and bonding capital variables showed moderate correlations (r = .43 ~ .57, ps < 0.01). Home cultural adjustment presented lower bivariate correlations (r = .24 ~ .36, ps < 0.01) than host cultural adjustment (r = .39 ~ .43, ps < 0.01).

As shown in Table 2, the test of hypothesized model fit indicated an inadequate fit with observed data. The goodness-of-fit test was statistically significant, χ2 (28) = 202.98, p < .001, χ2/df = 7.25, CFI = 0.795, TLI = 0.642, RMSEA = 0.173. Moreover, most direct and indirect hypotheses paths did not reach statistical significance at the 0.05 critical level. After trimming insignificant paths and re-evaluating model fit sequentially, the final model reached the adequate model fit with the Chi-square value improved up to 156 (from χ2 (28) = 202.98, p < .001 to χ2 (17) = 47.11, p = .001), χ2/df = 2.77, CFI = 0.950, TLI = 0.926, RMSEA = 0.092. The final model path and estimation as shown in Fig. 3; Table 2.

The standardized factor loadings of latent variable from skills, emotional, and participation were high (0.86, 0.80, and 0.78, ps < 0.001) shown in Table 2. The endogenous variables bridging capital accounted for the largest amount of variance with R2 = 0.372. The next was bonding capital, host and home cultural adjustment, with R2 = 0.246, R2 = 0.231, and R2 = 0.208, respectively.

In the final model (Fig. 3; Table 2), only using social media for cognitive learning had a direct impact on the latent variable engagement (H1c) which showed statistical and positive significance (β = 0.316, p < .001). Using social media to maintain close relationships (H1b) did not predict learning engagement, however, after adding the mediating effect of bridging capital (H3b), the results showed a positive influence on learning engagement (β = 0.176, p < .001). Bridging capital significantly and positively influenced learning engagement. In contrast, bonding capital did not demonstrate the same effect. In hypothesis H4a, using social media for new resources influenced host cultural adjustment, then was mediated by bridging capital to impact engagement. The mediation of host and bridging was positively and statistically significant, but showed a small effect (β = 0.092, p < .001). None of H2a-d was significant. Although the social media uses on cultural adjustment effect were partially held, the two cultural adjustment subscales had no direct effect on learning engagement. The hedonic type of social media use neither directly (H1d) nor indirectly (H2d) affected international students’ learning engagement (β = − 0.033, p = .76). We removed this variable from the final model. Although close relationships had a significant effect on bonding, there was no significant indirect path (H3c, H4b) on learning engagement. Home cultural retainment (β = − 0.008, p = .926) and bonding capital (β = 0.219, p = .117) were two endogenous variables that were removed from the final model due to no significant effect on learning engagement.

10 Discussion

The SEM path analysis results in the final model indicated that three out of the four uses social media for international students, direct or indirect, improved their learning engagement, except for hedonic use. In terms of the direct effect on engagement, cognitive social media use produced statistical significance (β = 0.316, p < .001), which was consistent with our hypothesis (H1c) and previous research. According to Ansari and Khan (2020), college students in India have diversified social media communication groups and applied their resources to collaborative learning. Among the three cognitive learning activities, interaction with instructors contributed a higher coefficient degree (β = 0.450, p < .001) than knowledge sharing (β = 0.247, p < .001) and peer discussion (β = 0.210, p < .001) on students’ learning engagement. In Ansari and Khan’s (2020) research, the engagement variable data were collected using four statements adapted from Al-Rahmi and his colleagues’ research (2018) regarding factors affecting learning performance through social media in Malaysia. Instead of using a single summation of all items, we applied latent variables that constitute three subconstructs (i.e., skills, emotional, participation) that we adapted from the SCEQ (Handelsman et al., 2005). The complexity of this learning engagement construct has been discussed in the literature review section. Grounded in Skinner’s (2016) concept, the self and context factors are two distinct facilitators affecting the students’ strategies to stay engaged, and these two factors may impact the three subcomponents (i.e., skills, emotional, participation) differently. For example, when college students cognitively apply skillful strategies, but suffer emotionally from the anxiety of being unable to compete with others, their learning engagement summation decreases due to not being able to optimize their participation in learning activities (Schwinger & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2012). The factor loadings in the hypothesized and final model varied but consistently indicated that skills engagement had the highest factor loading, the second was emotional, followed by participation (Table 2).

Studying the mediation effect of bridging capital and host cultural adjustment unraveled two indirect paths leading to the significant improvement of international students’ learning engagement. Bridging was a pivotal factor that appeared in two paths to mediate the effect of two types of social media usage on engagement, respectively. Bridging was mid-high and positively correlated with other exogenous and endogenous variables (Table 1). In the final model estimation (Table 2), the use of social media for close relationships positively predicted bridging capital and improved engagement (H3b). In previous literature, international students’ pre-existing relationships are often associated with strong ties (Lin et al., 2012; Phua & Jin, 2011; Stefanone et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2020). Little research has discussed how international students’ use of social media to connect with family and friends could increase bridging capital. Cruwys and colleagues (2021) suggested that international students build connections with multiple groups of identities to ensure that resources are available when they encounter unexpected challenges. Pre-existing group memberships increase students’ possibilities in expanding new resources. Our research results indicate that using social media to strengthen communication in close relationships enables international students to simultaneously build weak and strong ties in the U.S. In this respect, we emphasize the significance of using social media to solidify close relationships to increase international students’ bridging and bonding capital and indirectly enhance their learning engagement.

With bridging capital as a mediator, the exogenous variable of new networks did not present a significant effect on learning engagement. While the insignificant indirect effect contradicted our hypothesis, the bridging capital’s mediation effect was advanced by adding the host cultural adjustment variable. In our final model, the significant mediation path (H4a) indicated that international students using social media for new resources positively impacted learning engagement through the mediation of their host cultural adjustment in the U.S. and bridging capital simultaneously (Fig. 3). The mediation of host cultural adjustment and bridging capital simultaneously explained the mechanisms that international students expanding their new social networks had a better cultural adjustment in the U.S. which also resulted in higher bridging capital. Our findings are supported by previous research about the benefits of better cultural adjustment. According to Intercultural Adaptation Model (IAM) (Cai & Rodríguez, 1997), individuals encountering cross-cultural communication have varied tendencies to adjust themselves to facilitate understanding or avoid communication. IAM suggests that sojourners’ adaptive effort depends on their previous intercultural experience. In this vein, international students’ use of social media to build new interactions highly relies on their host cultural adjustment, which consequently influences their bridging capital and learning engagement. Individuals with higher levels of bridging capital are usually more open-minded to adjusting to a new environment and more comfortable when their perceptions are challenged (Cao & Meng, 2020; Williams, 2006).

Glass and Westmont (2014) proposed that integrated acculturation is a resilience factor and suggested that cross-culture interactions with domestic students and local communities enhance international students’ sense of belonging and adjustment to college in the host culture context. Cross-culture communication buffers negative feelings and provides students with a sense of secure relationships when encountering discrimination, indirectly influencing academic success. Therefore, international students must expand their resources, e.g., make new friends with interests similar to theirs and participate in community activities to build their bridging capital both on and off the campus. Consequently, communication competency, combined with increased cross-cultural sophistication, can foster a lasting positive effect on students’ academic success.

Bonding capital is also meaningful for international students to maintain close and assured relationships, but it has no mediation effect in hypothesis testing. Although bonding presented moderate and significant associations with all four uses of social media and the home cultural variable, it failed to predict international students’ learning engagement. Moreover, bridging and bonding capital were moderately to largely correlated with each other (r = .63, p < .01). According to Cao and Meng (2020), international students from China with more contacts in intercultural networks presented higher bridging and higher bonding capital. Our research suggests that international students’ bridging capital plays a more prominent role in improving learning engagement than bonding for international students using social media in the U.S. Therefore, bonding capital and home cultural adjustment are removed from the final model due to little impact on learning engagement.

The exogeneous variable related to hedonic use of social media was not included in the final model either. Hedonic use did not significantly lower levels of learning engagement, which contradicted our hypothesis. Instead, hedonic use improved home cultural adjustment, which was partially aligned with the hypothesis. Drawing from previous findings that better home cultural adjustment contributed to international students having better mental health (Chai et al., 2020; 2022; Cruwys et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021), future researchers can further explore the optimal utility of entertainment to as a form of stress relief and as a way to cope with challenges without significantly interfering learning.

11 Conclusion

Drawing from affordance theory, instead of focusing on the positive or negative effects of artifacts (social media platforms) on learning, we shift the attention to the actors (international students) and advocate for the strategic and purposeful use of social media. The aim of this research is to help international students and educators develop strategies and interventions to manage social media tasks and goals to improve student learning. We suggest consideration of both social and cultural factors when studying international students to uncover previous contradicted results by examining indirect effects. Bridging capital is a significant mediator that enables two uses of social media and host cultural adjustment to indirectly enhance learning engagement. Social distancing policies originating during the COVID-19 pandemic limited students’ attendance in activities that build bridging capital. Compared to domestic students, international students have fewer opportunities and channels to reach out. When consider international students’ academic activities, the influence of their social needs and cultural adjustment should not be overlooked. Higher bridging capital and host cultural adjustment to the U.S. resulted in higher levels of academic engagement. More specifically, international students who interact with American peers, faculty, and local residents by participating in community activities or other opportunities have better integration into U.S. society and have more bridging capital. The strengths that facilitate cross-culture communication require contribution from multiple entities.

In addition to individual efforts, college administrators should provide more opportunities for international and domestic students to engage in cross-cultural interactions and conversations. For example, an “International Buddy Program” was organized at one university in which international students were paired with domestic students based on their registered interests to encourage cultural diversity and involvement. After being paired, the students meet each other in person. This same institution has provided international students with opportunities to use online conversation platforms to interact with domestic students and improve their communication competency. Through personalized, flexible online learning sessions, international students can improve their language proficiency by conversing in English or sharing experiences about their respective cultures. Activities like these should be organized and funded by universities.

12 Limitations

There were several limitations to the current study. First, although the participants were international students with a variety in ethnicity, nationality and race, this study did not divide them based on those differences. The small sample size (n = 209) encouraged treating the participants as a homogenous group. In future research, splitting the group based on these differences may find larger effects in result. Second, 77.5% of students reported that they were STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) majors, and a disproportionate number of responses were from graduate and doctoral students (61.7%), compared to 38.2% of undergraduate students. This sample distribution may create a response bias that hinders a clearer understanding of the broader population of international undergraduate students.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alias, N., Othman, M. S., Marin, V. I., & Tur, G. (2018). A model of factors affecting learning performance through the use of social media in malaysian higher education. Computers & Education, 121, 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.02.010.

Ali-Hassan, H., Nevo, D., & Wade, M. (2015). Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: the role of social capital. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 24(2), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2015.03.001.

Al-Oraibi, A., Fothergill, L., Yildirim, M., Knight, H., Carlisle, S., O’Connor, M., & Blake, H. (2022). Exploring the psychological impacts of COVID-19 social restrictions on international university students: a qualitative study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(13), 7631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137631.

Ansari, J. A. N., & Khan, N. A. (2020). Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning. Smart Learning Environments, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-020-00118-7.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong. Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3),497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Berk, R. A., Freedman, D., Pisani, R., & Purves, R. (1996). Statistics. Contemporary Sociology, 25(4), 442. https://doi.org/10.2307/2077035.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J., Sam, D., & Vedder, P. (Eds.). (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity and adaptation across national context. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Blackmore, J., Tran, L., Hoang, T., Chou-Lee, M., McCandless, T., Mahoney, C., Beavis, C., Rowan, L., & Hurem (2021). Affinity spaces and the situatedness of intercultural relations between domestic and international students in two australian schools. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2022.2026892.

Blasco-Arcas, L., Buil, I., Hernández-Ortega, B., & Sese, F. J. (2013). Using clickers in class. The role of interactivity, active collaborative learning and engagement in learning performance. Computers & Education, 62, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.019.

Brunsting, N. C., Zachry, C., & Takeuchi, R. (2018). Predictors of undergraduate international student psychosocial adjustment to US universities: a systematic review from 2009–2018. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 66, 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.06.002.

Cai, D. A., & Rodríguez, J. I. (1997). Adjusting to cultural differences: the intercultural adaptation model. Intercultural Communication Studies, 1(2), 31–42. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.690.9891&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Cao, C., & Meng, Q. (2020). Effects of online and direct contact on chinese international students’ social capital in intercultural networks: testing moderation of direct contact and mediation of global competence. Higher Education, 80(4), 625–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00501-w.

Cao, G., & Tian, Q. (2022). Social media use and its effect on university student’s learning and academic performance in the UAE. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1801538.

Chai, D. S., Chae, C., & Lee, J. (2022). International students’ psychological capital in Japan: Moderated mediation of adjustment and engagement. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 59(1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2021.1943417.

Chai, D. S., Van, H. T. M., Wang, C. W., Lee, J., & Wang, J. (2020). What do international students need? The role of family and community supports for adjustment, engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of International Students, 10(3), 571–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2021.1943417.

Chang, C. T., Tu, C. S., & Hajiyev, J. (2019). Integrating academic type of social media activity with perceived academic performance: a role of task-related and non-task-related compulsive internet use. Computers & Education, 139, 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.05.011.

Chawinga, W. D. (2017). Taking social media to a university classroom: teaching and learning using Twitter and blogs. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0041-6.

Cleary, T. J., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2012). A cyclical self-regulatory account of student engagement: theoretical foundations and applications. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student Engagement. Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_11.

Cho, J., & Yu, H. (2015). Roles of university support for international students in the United States: analysis of a systematic model of university identification, university support, and psychological well-being. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315314533606.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdf/10.1086/228943.

Cruwys, T., Ng, N. W., Haslam, S. A., & Haslam, C. (2021). Identity continuity protects academic performance, retention, and life satisfaction among international students. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 931–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12254.

Demes, K. A., & Geeraert, N. (2014). Measures matter: scales for adaptation, cultural distance, and acculturation orientation revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113487590.

Deng, L., & Yuan, K. H. (2022). Which method is more powerful in testing the relationship of theoretical constructs? A meta comparison of structural equation modeling and path analysis with weighted composites. Behavior Research Methods, 1(20). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01838-z

Dillman, D. A. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and Mixed-Mode surveys: the tailored design method (4th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: what is tt? Why does it matter?. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement. Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_5.

Flanigan, A. E., & Babchuk, W. A. (2015). Social media as academic quicksand: a phenomenological study of student experiences in and out of the classroom. Learning and Individual Differences, 44, 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.11.003.

Flanigan, A. E., & Kiewra, K. A. (2018). What college instructors can do about student cyber-slacking. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9418-2.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059.

Gibson, J. J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence.

Glass, C. R., & Gesing, P. (2018). The development of social capital through international students’ involvement in campus organizations. Journal of International Students, 8(3), 1274–1292. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1254580.

Glass, C. R., Kociolek, E., Wongtrirat, R., Lynch, R. J., & Cong, S. (2015). Uneven experiences: the impact of student-faculty interactions on international students’ sense of belonging. Journal of International Students, 5(4), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v5i4.400.

Glass, C. R., & Westmont, C. M. (2014). Comparative effects of belongingness on the academic success and cross-cultural interactions of domestic and international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.04.004.

Gomes, C. (2015). Negotiating everyday life in Australia: Unpacking the parallel society inhabited by Asian international students through their social networks and entertainment media use. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(4), 515-536. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.992316

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice–Hall, International Inc.

Handelsman, M. M., Briggs, W. L., Sullivan, N., & Towler, A. (2005). A measure of college student course engagement. Journal of Educational Research, 98, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.98.3.184-192.

Hox, J. J., & Bechger, T. M. (1998). An introduction to structural equation modeling. Family Science Review, 11, 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/01688638808402800.

Humphrey, A., & Forbes-Mewett, H. (2021). Social value systems and the mental health of international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of International Students, 11(S2), 58–76.

Hutchby, I. (2001). Technologies, texts and affordances. Sociology, 35(2), 441-456. https://doi.org/10.1177/S0038038501000219

Institute of International Education (2021). Open Doors 2021. https://opendoorsdata.org/annual-release/international-students/

Jordan, M., & Hartocollis, A. (2020). U.S. rescinds plan to strip visas from international students in online classes The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/14/us/coronavirus-international-foreign-student-visas.html

Kabilan, M. K., Ahmad, N., & Abidin, M. J. Z. (2010). Facebook: An online environment for learning of English in institutions of higher education?. Internet and Higher Education, 13(4), 179–187. Elsevier Ltd. Retrieved September 30, 2022 from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/108382/

Kim, Y. S., & Kim, Y. Y. (2016). Ethnic Proximity and Cross-Cultural Adaptation: A Study of Asian and European Students in the United States. Intercultural Communication Studies, 25(3).

Kim, E., & Hogge, I. (2021). Microaggressions against asian international students in therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 52(3), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000383.

Kim, Y. Y. (1988). Communication and cross-cultural adaptation: an integrative theory. Clevedon, United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters.

Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming Intercultural: an integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication.

Kunka, B. A. (2020). Twitter in higher education: increasing student engagement. Educational Media International, 57(4), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2020.1848508.

Li, X., & Chen, W. (2014). Facebook or Renren? A comparative study of social networking site use and social capital among chinese international students in the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.012.

Lin, J. H., Peng, W., Kim, M., Kim, S. Y., & LaRose, R. (2012). Social networking and adjustments among international students. New Media & Society, 14(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811418627.

Mbawuni, J., & Nimako, S. G. (2015). Critical factors underlying students’ choice of institution for graduate programmes: empirical evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Higher Education, 4(1), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v4n1p120.

Moon, C. Y., Zhang, S., Larke, P. J., & James, M. C. (2020). We are not all the same: a qualitative analysis of the nuanced differences between chinese and south korean international graduate students’ experiences in the United States. Journal of International Students, 10(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v10i1.770.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). International handbook of emotions in education. New York: Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203148211-5/introduction-emotions-education-reinhard-pekrun-lisa-linnenbrink-garcia.

Phua, J., & Jin, S. A. A. (2011). “Finding a home away from home”: the use of social networking sites by Asia-Pacific students in the United States for bridging and bonding social capital. Asian Journal of Communication, 21(5), 504–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2011.587015.

Pozzi, G., Pigni, F., & Vitari, C. (2014). Affordance theory in the IS discipline: A review and synthesis of the literature. In AMCIS 2014 Proceedings. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01923663

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of american community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Roberts, T. S. (2005). Computer-supported collaborative learning in higher education. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-408-8.ch001.

Russell, J., Rosenthal, D., & Thomson, G. (2010). The international student experience: three styles of adaptation. Higher Education, 60(2), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9297-7.

Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Deumert, A., Nyland, C., & Ramia, G. (2008). Loneliness and international students: an australian study. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12(2), 148–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307299699.

Schwinger, M., & Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2012). Effects of motivational regulation on effort and achievement: a mediation model. International Journal of Educational Research, 56, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.07.005.

Skinner, E. A. (2016). Engagement and disaffection as central to processes of motivational resilience development. In K. Wentzel, & D. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 145–168). New York: Routledge.

Stathopoulou, A., Siamagka, N. T., & Christodoulides, G. (2019). A multi-stakeholder view of social media as a supporting tool in higher education: an educator–student perspective. European Management Journal, 37(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.01.008.

Stefanone, M. A., Kwon, K., & Lackaff, D. (2011). The value of online friends: networked resources via social network sites. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i2.3314.

Sun, X., Hall, G. C. N., DeGarmo, D. S., Chain, J., & Fong, M. C. (2021). A longitudinal investigation of discrimination and mental health in chinese international students: the role of social connectedness. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 52(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022120979625.

Tindell, D. R., & Bohlander, R. W. (2012). The use and abuse of cell phones and text messaging in the classroom: a survey of college students. College Teaching, 60, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2011.604802.

Tran, L. T., & Pham, L. (2016). International students in transnational mobility: intercultural connectedness with domestic and international peers, institutions and the wider community. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 46(4), 560–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2015.1057479.

Tsai, J. Y., Phua, J., Pan, S., & Yang, C. C. (2020). Intergroup contact, COVID-19 news consumption, and the moderating role of digital media trust on prejudice toward Asians in the United States: cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e22767. https://doi.org/10.2196/22767.

Tu, H. (2018). English versus native language on social media: international students’ cultural adaptation in the US. Journal of International Students, 8(4), 1709–1721. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1468074.

Tyson, D. F., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., & Hill, N. E. (2009). Regulating debilitating emotions in the context of performance: achievement goal orientations, achievement-elicited emotions, and socialization contexts. Human Development, 52(6), 329–356. https://doi.org/10.1159/000242348.

Van Horne, S., Lin, S., Anson, M., & Jacobson, W. (2018). Engagement, satisfaction, and belonging of international undergraduates at US research universities. Journal of International Students, 8(1), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1134313.

Wellman, B., Haase, A. Q., Witte, J., & Hampton, K. (2001). Does the internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital? Social networks, participation, and community commitment. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(3), 436–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640121957286.

Williams, D. (2006). On and off the ’net: scales for social capital in an online era. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 593–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00029.x.

Yu, Q., Foroudi, P., & Gupta, S. (2019). Far apart yet close by: social media and acculturation among international students in the UK. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 145, 493–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.09.026.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, J., Lee, S., Wang, Ch. et al. Impact on social capital and learning engagement due to social media usage among the international students in the U.S.. Educ Inf Technol 28, 8027–8050 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11520-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11520-8